1. Introduction and Motivation

Reaction–diffusion equations, and more broadly diffusion-type partial differential equations, form a unifying mathematical framework for transport, spreading, and interaction phenomena across physics, chemistry, biology, and geometry. They model, among other things, heat conduction, mass transfer in reactive media, charge transport in semiconductors, population dynamics, and biological pattern formation. In such systems, diffusion acts to redistribute a scalar quantity u (temperature, concentration, density, etc.), while source or sink terms model production, decay, reaction, or nonlinear feedback. The nonlinear heat equation is a canonical representative of this class: it captures the competition between spatial smoothing induced by diffusion and potentially amplifying, saturating, or destabilizing effects encoded in the nonlinear source term. This interplay between transport and nonlinearity is tightly connected to questions of stability, pattern formation, blow-up, and the long-time structure of solutions.

While diffusion processes are often first studied on flat Euclidean domains, many physically relevant systems evolve on curved geometries [

1]. Examples include temperature redistribution on planetary atmospheres, morphogen transport and reaction on evolving biological membranes, chemical activity on spherical nanoparticles, and charge transport on curved interfaces [

2]. In all such cases, the underlying space is not

but a Riemannian manifold

, meaning a smooth manifold

M equipped with a Riemannian metric

g. The metric

g is a smoothly varying, positive-definite inner product on the tangent space at each point of

M. This structure provides the geometric foundation for measuring lengths, angles, areas, and curvature on the manifold, thus modifying the structure of the diffusion operator itself [

3].

The systematic analysis of PDE symmetries originates in the work of Sophus Lie, who developed the theory of continuous transformation groups and introduced what is now known as Lie group analysis of differential equations. The central idea is that one can algorithmically determine the continuous symmetries of a differential equation, use them to construct invariant solutions, reduce the number of independent variables, and, in some cases, integrate the resulting reduced equations exactly. This methodology was put into a general and mature form in the works of Ovsiannikov [

4], Olver [

5], Bluman and Cole [

6], Bluman and Kumei [

7], and Ibragimov [

8,

9], with further exposition available in texts such as those by Hydon [

10] and Stephani [

11].

For the classical linear heat equation

the admitted Lie point symmetry algebra is extremely large: it includes time and space translations, Galilean boosts, scaling of space and time, solution scaling, and even an infinite-dimensional ideal generated by solutions of the associated linear homogeneous equation. This algebra underlies the construction of similarity solutions, fundamental solutions, and self-similar blow-up/scaling laws.

For nonlinear diffusion equations of the general form

Lie symmetry classification results reveal precisely which functional forms of the diffusivity

and source term

lead to enlarged symmetry algebras. These classical classification studies show that nonlinearities are not arbitrary if one demands rich symmetry; instead, they must satisfy compatibility conditions that can be solved explicitly [

12,

13]. Such results are now standard in the Euclidean setting and have become part of the modern methodology for constructing exact solutions and similarity reductions of nonlinear parabolic equations [

14].

A major extension of this program is the analysis of diffusion-type equations on curved manifolds. On a Riemannian manifold

, the geometry enters both through the Laplace–Beltrami operator and through the allowed point symmetries of the PDE. The Laplace–Beltrami operator

is the natural generalization of the Euclidean Laplacian to a Riemannian manifold

. This operator governs diffusion and wave propagation on curved surfaces. Tsamparlis and Paliathanasis showed that, for the homogeneous heat equation on

,

the Lie point symmetries are generated by the homothetic algebra of the metric: specifically, Killing and homothetic vector fields of

g lift to point symmetries of the PDE [

15]. On constant-curvature manifolds such as spheres, this implies that the isometry group—namely, the group of all differentiable transformations of

M onto itself that preserve the metric

g—plays a direct role in the admitted symmetry algebra and in the associated similarity reductions. This observation connects diffusion on

with geometric analysis, spectral theory [

16,

17], and representation-theoretic approaches to parabolic and Schrödinger-type equations [

18], where the isometry or conformal groups act in a structured way on families of solutions.

Despite these advances, there remains a fundamental gap in the curved-geometry theory of nonlinear parabolic equations. In Euclidean space, the group classification of nonlinear diffusion equations with reaction terms is well established [

14,

19]; on Riemannian manifolds, however, the situation is dramatically less developed. In particular, a complete Lie point symmetry classification for a nonlinear reaction–diffusion equation on the two-sphere

with a general nonlinear source term

does not appear to have been carried out. The presence of curvature-dependent coefficients such as

and

in the spherical Laplace–Beltrami operator leads to determining equations for the symmetry generators that are qualitatively different from their flat analogs, and this obstructs naive transplantation of Euclidean classification results to the spherical setting.

The present work addresses this gap. We consider the nonlinear reaction–diffusion equation on the unit sphere,

where

is the dependent variable as a function of colatitude

x, longitude

y, and time

t, and

is an arbitrary nonlinear reaction term with

. We carry out a full Lie symmetry analysis of Equation (

4), solving the associated determining system. Our first result establishes that, for a generic nonlinear source term

, the Lie point symmetries of Equation (

4) reduce to the rotational Killing fields of the sphere together with time translation. No additional point symmetries survive for a genuinely nonlinear

. In particular, none of the familiar flat-space symmetries for diffusion-type equations, such as spatial translations, Galilean boosts, scaling of space and time, or rescalings in the dependent variable

u, are admitted on

for a nonlinear source term. This establishes that curvature enforces a universal minimal symmetry algebra for nonlinear reaction–diffusion on the sphere.

We then carry out a group classification analysis [

20] for the source term

. By deriving and solving the functional constraints that arise from the invariance condition, we identify all candidate nonlinearities (polynomial, power-law, exponential, and logarithmic forms among them) that could in principle enlarge the symmetry algebra. Such nonlinearities are known, in the Euclidean setting, to produce extended Lie algebras and to admit similarity reductions of a special type. We show that, on

, none of them lead to any additional point symmetries once the full geometric determining equations are enforced.

Having established the admitted symmetry algebra, we next construct curvature-adapted reductions using optimal systems of one- and two-dimensional subalgebras. These reductions transform the original -dimensional equation into either -dimensional parabolic equations with curvature-induced terms or into stationary ordinary differential equations in a single invariant variable.

Finally, we examine a specific nonlinear source term,

, for which certain reduced ODEs admit an additional one-parameter Lie symmetry at the ODE level, even though the full PDE does not acquire any new global point symmetry. This hidden symmetry allows us to integrate the reduced ODEs explicitly and construct exact stationary solutions on

in closed form. These solutions are expressed using elementary functions such as

,

, and

, and they represent nontrivial nonlinear steady states shaped jointly by curvature and reaction. To our knowledge, these explicit closed-form steady-state solutions are among the first exact nonlinear equilibrium profiles for a reaction–diffusion equation with a non-polynomial source on the sphere. These results clarify how intrinsic curvature constrains, and in some cases enables, the symmetry-driven analysis of nonlinear parabolic equations. They also provide a geometric foundation for future investigations of anisotropic diffusion, higher-dimensional compact manifolds, and stability of invariant steady states in reaction–diffusion systems on curved surfaces [

15,

18].

In summary, this work provides a complete classification of point symmetries for nonlinear reaction–diffusion on and illustrates how curvature constrains the symmetry algebra. It also demonstrates how, for special choices of the nonlinearity, one can obtain exact invariant solutions through a combination of symmetry reduction and hidden integrability. These results establish a foundation for further investigations, such as extending the classification to higher-dimensional spheres or to manifolds with varying curvature, and examining how curvature-induced symmetry constraints influence pattern formation in nonlinear diffusion systems.

2. Mathematical Preliminaries and Geometric Setting

A rigorous Lie symmetry analysis of a partial differential equation on a curved manifold requires a clear formulation of the underlying geometry, the associated differential operators, and the transformation properties of dependent and independent variables. This section outlines the geometric structure of the two-dimensional sphere

, derives the corresponding Laplace–Beltrami operator, and summarizes the fundamental elements of Lie group theory used in the symmetry classification of the nonlinear heat-type Equation (

4).

Diffusion on a Riemannian manifold

is governed by the Laplace–Beltrami operator,

which generalizes the Euclidean Laplacian to curved spaces [

16,

17]. The presence of geometric coefficients in

directly influences transport and equilibration and fundamentally alters the admitted symmetry structure of the PDE. For the unit sphere

with coordinates

, where

x denotes colatitude and

y the azimuthal angle, the induced metric

has determinant

and inverse tensor

. Substituting into the definition above yields the Laplacian operator

which governs diffusion on the sphere. The geometric coefficients

and

illustrate curvature effects: they vanish in the flat limit, recovering the Euclidean Laplacian. The isometry group of

is

, generated by three Killing vector fields corresponding to infinitesimal rotations about orthogonal axes [

11]. These fields form the core of the symmetry algebra of

and hence of any isotropic diffusion process on the sphere. From the perspective of symmetry, the fact that

admits a three-dimensional space of Killing vector fields (infinitesimal rotations) suggests that any rotationally invariant diffusion equation on

will inherit those geometric symmetries. A central question is whether these are the only point symmetries or whether one can recover on the sphere some of the richer symmetry structures known in the flat case.

The Lie group method, introduced by Sophus Lie and later developed in modern form by Ovsiannikov [

4], Olver [

5], Bluman and Kumei [

7], and Ibragimov [

8], provides a systematic means of identifying continuous transformations that map solutions of a PDE into other solutions.

A one-parameter local Lie group of transformations is a smooth family of transformations, parameterized by a real variable

defined in a neighborhood of zero, acting on the space of variables

and satisfying the local group properties. In particular, the family contains the identity transformation at

and is locally closed under composition and inversion. Such a local group is completely characterized, up to its domain of definition, by its infinitesimal generator, which is the vector field

X obtained by differentiating the transformation with respect to

at

. The coefficients of

X, denoted

,

,

, and

, describe the first-order infinitesimal action of the group on each coordinate. A one-parameter local Lie group acts on

as

where

is an infinitesimal parameter and

are smooth functions defining the group’s infinitesimal generator,

The generator acts on derivatives of

u through its second prolongation

, obtained via total differentiation [

5,

10].

In coordinates, the second prolongation can be written as

where the coefficients

and

are the prolonged infinitesimals associated with the first- and second-order derivatives of

u. They are defined by

with indices

and summation over repeated indices. Here

denotes the total derivative with respect to the variable

i.

Explicitly, the total derivative with respect to

x is given by

with analogous expressions for

and

. These prolonged infinitesimals determine how the infinitesimal generator

X acts on derivatives of

u and are required to enforce the invariance condition

where

denotes the governing partial differential equation.

The invariance condition (

12) yields a linear overdetermined system for the infinitesimals

. Solving this system determines the Lie point symmetries admitted by the equation.

For the nonlinear heat-type Equation (

4), dependence on an arbitrary function

typically restricts the infinitesimals to geometric symmetries of

and time translations [

13,

15].

Once the infinitesimal generators are known, invariant reductions follow by solving the characteristic system

which defines the similarity variables that reduce the PDE to a lower-dimensional form. On

, the dominant symmetries correspond to the rotational Killing fields of

, leading to reductions that represent axisymmetric diffusion, rotating wave modes, or stationary spherical harmonics [

20]. These invariant solutions possess direct geometric and physical meaning, describing diffusion patterns constrained by curvature and global symmetry. In

Section 5 we derive several such reductions and in

Section 6 we obtain closed-form invariant solutions for the special nonlinear source

.

Remark 1. In this paper, we focus on genuinely nonlinear source terms (). It is worth noting that, in the excluded linear or linearizable cases (for example, , including the homogeneous linear case ), the symmetry algebra of the linear heat equation is known to be much larger. In particular, when is linear, the superposition principle introduces an infinite-dimensional symmetry associated with arbitrary solutions of the homogeneous linear equation [5]. One also recovers additional point symmetries such as scalings in u. 3. Minimal Symmetry Algebra and Group Classification

This section establishes the minimal Lie point symmetry structure of the nonlinear heat-type equation on the sphere, (

4), and then investigates when additional symmetries arise. Using the standard Lie algorithm (second prolongation and invariance condition) [

5,

7], we derive the full determining system and solve it in the generic case of an arbitrary nonlinear source

. The main outcome (Theorem 1) is that the symmetry algebra is precisely

, generated by spatial rotations on

and time translation. We then turn to the group classification problem: for special choices of

, the algebra may extend beyond this minimal form. The analysis provides the symmetry foundations for the reductions and exact solutions constructed in the subsequent sections.

Theorem 1. Consider the nonlinear evolution Equation (4): For a generic function such that , the full Lie point symmetry algebra is four-dimensional and generated by The subalgebra is isomorphic to (rotations in ), and T (time translation) commutes with it, so the algebra is .

Proof. We begin with the general infinitesimal generator for a Lie point symmetry:

where

are the infinitesimals to be determined. Let

denote the second prolongation of

X. The invariance condition requires that

The second prolongation is given by

Applying

to Equation (

4) and equating coefficients of various derivative terms to zero yields the following system of determining equations:

We now solve this system systematically using a triangulation procedure based on techniques for obtaining differential Gröbner bases developed by Mansfield [

21].

From equations

,

, and

,

we immediately obtain that

,

, and

are independent of

u:

From equation

,

, we deduce that

is at most affine in

u:

with corresponding partial derivatives

The equations

,

,

,

, and

provide kinematic couplings between the infinitesimals:

We can eliminate

in favor of

and

using

Since the determining equations provide expressions for

,

, and

in terms of

and

, the existence of a smooth function

imposes the corresponding compatibility (integrability) conditions obtained by commuting mixed partial derivatives, namely

Applying the first identity

yields

which simplifies to

Next, applying

and using

(

) and

(

),

yielding

From

and

(cross-differentiation), we obtain

Thus far,

can be recovered from

and

via the three first-order relations above, and

must satisfy Equations (

31)–(

34).

Now we substitute the expression for

into equations

using Equation (

24):

Using Equations (

31)–(

34), these reduce to

Hence only.

Now we analyze equation

with

and

:

For a generic nonlinear function

, the term

depends explicitly on

u while the other terms depend only on

. This forces the coefficient of

to vanish, requiring

. Then Equation (

36) reduces to

Since

f and

depend only on

u while the remaining terms depend only on

, the generic case implies that

Thus, for an arbitrary nonlinear function

,

Using

:

then gives

and

, and Equation (

31) reduces to

From : and : (no t-dependence), we get ; hence, . With and , we conclude that is constant: .

We now recover

from

Differentiating in

y and using

with

yields

, so

. Writing

, we obtain

Finally, the general solution is given as

where

are arbitrary constants.

Activating one constant at a time, we obtain the basis vector fields:

Therefore, the full symmetry algebra for generic is the span of . Here satisfy the commutation relations; T commutes with them. □

Without forcing , equation leads to admissible forms of f (e.g., linear , power laws, exponentials, etc.). For each candidate f, one solves the split from to determine , and possibly relax .

Remark 2. For arbitrary nonlinear , the determining equations force , so no scaling or superposition symmetry in u occurs. The spatial generators form the Killing algebra of the round 2–sphere with metric ; hence, Time translations commute with all spatial generators. Therefore the full Lie symmetry algebra is The commutator structure of is given in Table 1. 4. Classification of Nonlinearities Potentially Admitting Extended Point Symmetries

In the context of nonlinear heat-type equations on curved geometries such as the unit sphere, identifying the precise forms of the nonlinear source term that could potentially admit enlarged Lie point symmetry algebras is both mathematically rich and physically insightful. In this section, we rigorously derive the compatibility constraints that govern such symmetry extensions and prove that, despite a wide variety of candidate nonlinearities, the geometry of the sphere enforces severe restrictions that ultimately yield a minimal symmetry algebra.

To determine which nonlinearities

may yield extended point symmetries beyond the canonical rotational and time-translation invariance on the sphere, we note that the determining system reduces the symmetry condition involving

to the scalar ODE:

This equation governs all nonlinearities that could, in principle, admit symmetry extensions through nonzero a, b, or .

Starting from the determining equation

, we repeatedly differentiate with respect to

u to obtain a hierarchy of linear relations involving

,

, and higher derivatives of the source term

. By taking appropriate linear combinations of these relations, the auxiliary quantities

and

are eliminated, yielding a single compatibility condition that factors into a differential expression depending only on

multiplied by

. If

, this condition is identically satisfied for arbitrary

. Assuming that

, the elimination procedure leads to the fifth-order nonlinear differential constraint on

:

The general solution of Equation (

56) identifies the following families of nonlinear functions

as the only possible forms that could yield extended symmetries:

| 1. Quadratic: | ; |

| 2. Cubic: | ; |

| 3. Exponential: | , ; |

| 4. Power Law: | ; |

| 5. Logarithmic: | ; |

| 6. Mixed Logarithmic: | .

|

Each candidate nonlinearity is subsequently tested against the full determining system to rigorously verify whether it produces additional independent symmetry generators beyond the minimal algebra.

Theorem 2. Let be a nonlinear reaction term in Equation (4). Then no nontrivial solution of the classification Equation (56) produces an enlargement of the point symmetry algebra on the sphere. In particular, for every nonlinear , the full Lie point symmetry algebra of Equation (4) is generated by the spherical rotations and the time translation.

Proof. From the determining equations

–

, we know that

i.e.,

are independent of

u, and

is affine in

u.

The kinematic subsystem

expresses

in terms of

and

and enforces the wave-type and spherical compatibility relations

In particular, unless

, the left-hand side depends on

y while the right-hand side depends only on

x, so consistency on

forces

Next, insert

into

,

,

. Using the relations

and

, these reduce to

If

or

, then

and

must be constant, so

a itself must be constant in

. In this case,

, and likewise

. Consequently

all vanish in

, and the

f-dependent invariance condition

simplifies to

This scalar ODE in u is the algebraic obstruction for extending the symmetry beyond .

We now analyze Equation (

63) for the canonical nonlinearities obtained from the classification Equation (

56).

Case 1: Quadratic nonlinearity. Let

; thus,

. Substituting into Equation (

63) and equating coefficients of

gives

Thus, unless

, the parameters must satisfy

, i.e.,

is a perfect square. However, the geometric compatibility condition (

60) forces

on

, cf. (

61). Hence

, and therefore

,

. No additional symmetry survives.

Case 2: Cubic nonlinearity. Let

; thus,

. Substituting into Equation (

63) and comparing powers of

u yields

together with further linear relations among

. As in the quadratic case, these relations admit

only if

are constants and

is constant. But then the spherical compatibility again enforces

; hence,

. Thus even the perfect cube form

fails to generate an extra point symmetry on

.

Case 3: Exponential nonlinearity. Let

with

. Then

. Inserting into Equation (

63) gives a linear combination of the functionally independent terms

,

,

u, and 1. The

component forces

. The remaining terms then imply that

, but the spherical compatibility (

61) yields

, so

. Thus

. Hence, no additional symmetry arises.

Case 4: Power nonlinearity. Let

with

and

m not reducing to a lower-degree polynomial. Then

. Substituting into Equation (

63) and isolating the distinct powers

and

shows that

The only way this can hold for all u with nonlinear is , ; hence, .

Case 5: Logarithmic nonlinearity. Let

; thus,

. The most singular term

in Equation (

63) forces

. The mixed

and

terms then force

. The remaining linear terms again collapse under

.

Case 6: Mixed logarithmic nonlinearity. Let

; thus,

. The distinct functional dependencies

in Equation (

63) imply that

,

, and then

.

Therefore, in every admissible nonlinear case produced by Equation (

56), consistency with the spherical determining equations enforces

With we also have from , and the kinematic subsystem then reduces exactly to the Killing algebra of the round 2-sphere together with time translation. These span , and no further generator survives. □

We now examine explicitly how commonly used nonlinearities, particularly power-law and exponential reaction terms, fit within the classification result of Theorem 2. Consider first the power-law family

or, more generally,

with

. In Euclidean space, such nonlinearities are known to generate additional scaling or dilation symmetries for specific values of

n. In the present spherical setting, however, substitution of these forms into the invariance condition (

55) leads to algebraic constraints that are incompatible with the geometric determining equations unless

. Consequently, no scaling or amplitude symmetry survives, and the admitted Lie point symmetry algebra remains

for all genuine power-law nonlinearities.

A similar conclusion holds for the exponential nonlinearity (and its affine generalizations ). Although exponential source terms frequently produce extended symmetry algebras in flat-space diffusion equations, on the curvature-dependent compatibility conditions force the time-scaling parameter to vanish. As a result, the exponential nonlinearity does not enlarge the point symmetry algebra of the full PDE beyond rotations and time translation.

These results emphasize a fundamental geometric effect: while the classification equation admits power-law and exponential nonlinearities at a formal level, the curvature-induced terms in the determining equations eliminate the corresponding symmetry extensions.

Remark 3. The quadratic perfect square and perfect cube nonlinearities, which in flat Cartesian geometries sometimes trigger dilation- or Galilean-type extensions, do not produce additional point symmetries on , as the curvature enters through the and terms in the determining equations and forces , collapsing any potential amplitude or scaling symmetry in u. Thus the rotational isometries of the sphere and time translation exhaust the Lie point symmetries for all nonlinear .

6. Exact Symmetry Reductions and Closed-Form Solutions for a Nonlinear Source Term

In this section, we construct exact solutions of the nonlinear heat equation on the two-sphere

This choice lies within the exponential family discussed in

Section 4. For a generic

, Equation (

4) admits only the minimal Lie algebra

, generated by the rotations of the sphere and time translation. However, when

obeys certain compatibility conditions in the determining equations, the reduced equations obtained from invariant ansatzes admit extra point symmetries. This choice

is non-generic in that it is precisely one of the functional forms that allows for nonzero constants for the infinitesimals

,

a, and

b in the original determining system before the geometric constraints are fully imposed. These nonzero constant values for

and the affine components of

(

) are essential to generating a non-trivial similarity solution.

Although the curvature of ultimately forces for the full PDE, the specific structure of this exponential nonlinearity, when substituted into the f-dependent invariance condition, coincides with the integrability conditions required for the reduced ODEs to possess an additional hidden one-parameter first-order Lie symmetry. That extra symmetry allows for a second reduction by invariants, which makes the ODE explicitly integrable and produces closed-form solutions. In geometric terms, curvature does not create new global point symmetries of the full PDE but, in special nonlinear cases, it still permits axisymmetric invariant profiles that can be written analytically. We use this extra symmetry to obtain exact nonlinear steady states solutions for a reaction–diffusion equation on the sphere. To our knowledge, these are among the first explicit closed-form nonlinear steady states for a reaction–diffusion equation with a non-polynomial source on .

6.1. Rotationally Deformed Reductions Using

Referring to

Section 5.2.1 and assuming invariance under the subalgebra

, the dependent variable

is expressed as a function of a single invariant

. Substituting this ansatz into Equation (

82) gives the reduced ODE

Equation (

83) admits the additional Lie point symmetry

Using the invariants

the ODE is transformed into the system

Eliminating

yields

where

k is a constant of integration. Reverting to the original variables,

Equation (

88) is separable and integrable in three distinct cases:

,

, and

.

All three solution forms corresponding to this subalgebra are defined on the entire spherical surface with the invariant variable taking values in . Each solution is smooth for , though singular behavior may occur as , corresponding to specific great circles where the invariant coordinate reaches its limiting value. By construction, these solutions are invariant under the one-parameter Lie rotation generated by combined with the time-translation T for steady states. Geometrically, this invariance implies that the temperature field remains constant along circular orbits of a fixed rotational axis lying in the equatorial plane.

These families represent steady-state dipolar temperature distributions on the unit sphere

. One lobe of the sphere, where

, corresponds to a warm region, while the opposite lobe, where

, is cooler. The nonlinear source term

acts as a distributed heat sink, stronger in hotter regions, which balances diffusion to maintain equilibrium.

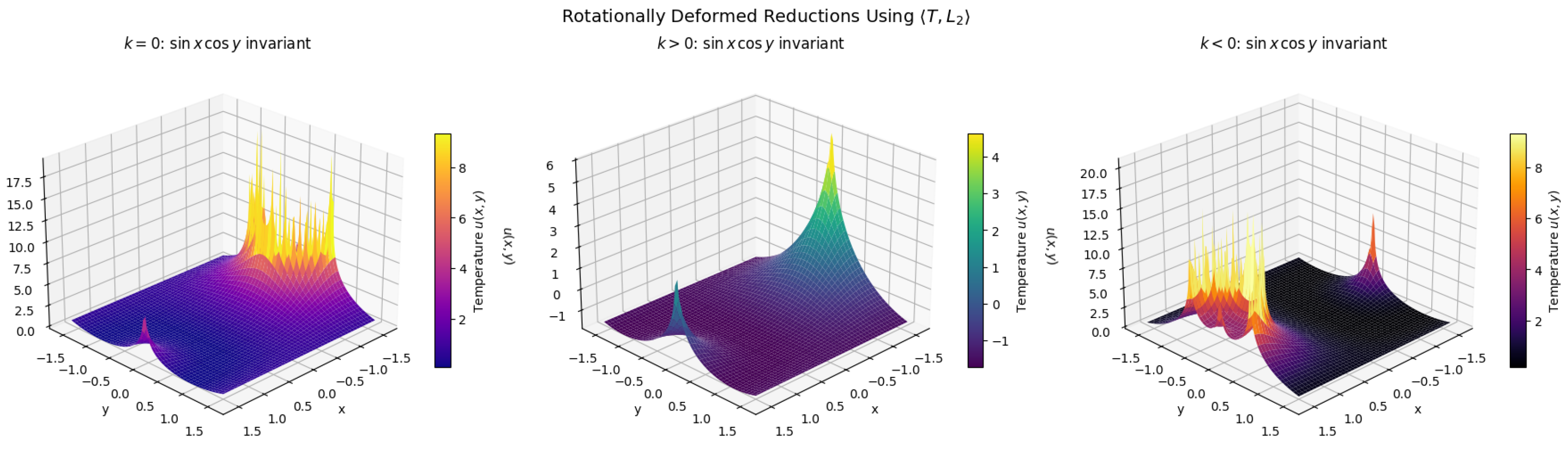

Figure 1 illustrates these solutions for representative values of

k. The parameter

C shifts the profile while

k controls the contrast between the two lobes.

6.2. Rotationally Deformed Reductions Using

Referring to

Section 5.2.2 and assuming invariance under the subalgebra

, the dependent variable

is expressed as a function of a single invariant

. Substituting this ansatz into Equation (

82) gives the reduced ODE

Equation (

92) admits the additional Lie point symmetry

Using the invariants

the ODE is transformed into the system

Eliminating

yields

where

k is a constant of integration. Reverting to the original variables,

Equation (

97) is separable and integrable in three distinct cases:

,

, and

.

These solutions also cover the entire sphere. Invariance under , together with T, corresponds to rotation about an axis orthogonal to that associated with . Consequently, the temperature is constant along orbits of this perpendicular rotation, producing a pattern identical in form to the case but rotated by on the sphere.

The nonlinear reaction term

removes heat preferentially from the hot side, establishing a stable temperature contrast across the sphere. The dividing curve

serves as a thermal equator separating the two hemispheric zones. The qualitative behavior of the solution mirrors that of the

family, though the temperature maximum now aligns with the hot regions at

.

Figure 2 shows that these invariant solutions correspond to the same parameter choices as in

Figure 1 but are rotated about the polar axis in the azimuthal angle

y. This shift in the longitudinal position of the hot and cold regions illustrates the spherical symmetry of the problem.

6.3. Axisymmetric Reduction in x Using

Referring to

Section 5.2.3 and assuming invariance under the subalgebra

, the dependent variable

is expressed as a function of a single invariant

. Substituting this ansatz into Equation (

82) gives the reduced ODE

Equation (

101) admits the additional Lie point symmetry

which enables its reduction to quadrature. Using the invariants

the ODE is transformed into the system

Eliminating

yields

where

k is a constant of integration. Reverting to the original variables,

Equation (

106) is separable and integrable in three distinct cases:

,

, and

.

The axisymmetric solutions depend on the colatitude and are independent of the longitude. They remain regular throughout most of their interval, except possibly at the poles, where singular behavior may occur depending on k. Invariance under enforces azimuthal symmetry, meaning that the temperature is constant along each circle of latitude. These configurations are fully symmetric about the polar axis of the sphere.

This family corresponds to zonal or polar heat distributions in which temperature varies only with latitude. Depending on the parameter

k, the solutions can represent a hot polar cap that cools gradually toward the equator, a warm equatorial belt with cooler poles, or limiting cases featuring a hot or cold pole modeled by singular behavior. Each configuration represents a static equilibrium in which diffusion and nonlinear heat removal balance exactly. The function

is generally single-peaked or single-valley, reflecting one dominant temperature extreme along the polar axis.

Figure 3 shows typical profiles for these axisymmetric solutions. Notably, because of the spherical geometry, even moderate values of

or

can cause the profile to concentrate near one pole or the other, illustrating how curvature influences the spread of the pattern.