Abstract

In this paper, we introduce an Adams-type predictor–corrector method based on a modified graded mesh for solving Caputo fractional differential equations. This method not only effectively handles the weak singularity near the initial point but also reduces errors associated with large intervals in traditional graded meshes. We prove the error estimates in detail for both and cases, where is the order of the Caputo fractional derivative. Numerical experiments confirm the convergence of the proposed method and compare its performance with the traditional graded mesh approach.

Keywords:

fractional Adams method; Caputo fractional derivative; modified graded mesh; nonlinear fractional differential equations; numerical methods MSC:

65L06; 26A33; 65B05; 65L05; 65L20; 65R20

1. Introduction

In this paper, we introduce a fractional Adams method with a modified graded mesh for solving the following nonlinear fractional differential equation, with :

where are arbitrary real numbers and represents the Caputo fractional derivative, defined by:

with denoting the Gamma function and representing the smallest integer greater than or equal to . The function satisfies the Lipschitz condition with respect to the second variable, i.e.,

where L is a positive constant.

We shall focus only on the case , as does not appear to be of significant practical interest ([1], lines 4–5 on page 46). The error estimates for the case can be derived in a similar manner.

It is well-known that Equation (1) is equivalent to the following integral representation:

The existence and uniqueness of the solution to Equation (1) have been thoroughly discussed in [1].

The numerical solution of fractional differential equations (FDEs) has been a topic of significant research interest in recent decades due to their applications in fields such as physics, biology, and engineering [2,3]. Exact solutions for FDEs are often difficult to obtain. Therefore, it is necessary to develop some efficient numerical methods for solving FDEs.

In addition to Adams methods, other numerical techniques for solving FDEs have been extensively explored. One approach involves directly approximating the fractional derivative, as discussed in [4,5,6]. Another transforms the FDEs into equivalent integral forms, which are then solved using quadrature-based schemes [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Furthermore, alternative strategies, such as variational iteration [14], Adomian decomposition [15], finite-element [16], and spectral methods [17], have been developed to address specific FDEs.

The Adams methods, particularly the predictor–corrector variants, have received significant attention for their efficiency in solving FDEs. For instance, Deng [18] enhanced the Adams-type predictor–corrector method by incorporating the short memory principle of fractional calculus, thereby reducing computational complexity. Nguyen and Jang [19] introduced a new prediction stage with the same accuracy order as the correction stage, while Zhou et al. [20] developed a fast second-order Adams method on graded meshes to solve nonlinear time-fractional equations, such as the Benjamin–Bona–Mahony–Burgers equation. Moreover, Lee et al. [21] and Mokhtarnezhadazar [22] proposed an efficient predictor–corrector method based on the Caputo–Fabrizio derivative and a high-order method on non-uniform meshes, respectively. These advancements help reduce computational effort while maintaining high precision.

Among the many numerical methods available for solving FDEs, Diethelm et al. [1,23,24,25] provided the theoretical foundation for the fractional Adams method. They proposed an Adams-type predictor–corrector scheme on uniform meshes and provided rigorous error estimates under the assumption that . The method achieves convergence rates of for and for , where N is the number of the nodes of the time partition on . These results have since inspired various extensions and refinements. Liu et al. [26] introduced graded meshes to better handle the singular behavior of solutions near . Their analysis refined error estimates and demonstrated that graded meshes significantly improve accuracy for FDEs with initial singularities, making them a practical choice for challenging problems. Furthermore, fractional calculus is more flexible than classical calculus, and recently, some new fractional definitions have been developed (see [27]). These developments provide new perspectives and tools for the numerical solution of fractional differential equations.

In this paper, we propose a modified Adams-type predictor–corrector method with a modified graded mesh. This type of mesh was first introduced in [28]. The modified graded mesh employs a non-uniform grid near the initial point to capture weak singularities, while a uniform grid is used away from the initial point, effectively reducing numerical errors. Our approach not only preserves the advantages of traditional graded meshes but also further optimizes the grid distribution, improving the accuracy of the numerical solutions.

Let be a partition; we shall consider the following modified graded mesh [28]. Define as a positive monitor function:

where is a constant and . The mesh is constructed such that is evenly distributed, i.e.,

Define and choose a suitable such that for some . The modified graded mesh is defined as follows:

where . The grid points constitute a non-uniform grid, whereas the grid points form a uniform grid [28].

Let for , with being the approximation of . Suppose we know the approximate values , from other methods. For , we define the following predictor–corrector Adams method to solve Equation (3) for :

The predictor term in (5) is derived by approximating the integral ,

with the following approximation, ,

where is a piecewise constant function defined on as, ,

The corrector term in (6) is derived by approximating the same integral, ,

with the following approximation, ,

where is a piecewise linear function defined on as, ,

Here, the weights in (5) for are given in Appendix A.

The weights in (6) for , satisfy

Assumption 1

([26]). Let and satisfy for . There exists a constant such that:

Remark 1.

Assumption 1 characterizes the local behavior of near and indicates that exhibits a singularity at this point. It is evident that . A simple example is , where .

Our main results of this work are summarized in the following two theorems.

Theorem 1.

Suppose and satisfies Assumption 1. Assume that and are the solutions of Equations (3) and (6), respectively. Then, the following error estimates hold, with .

- 1.

- If , then we have

- 2.

- If , then we have

- 3.

- If , then we have

Theorem 2.

Suppose and satisfies Assumption 1. Assume that and are the solutions of Equations (3) and (6), respectively. Then, the following error estimates hold, with .

- 1.

- If , then we have

- 2.

- If , then we have

- 3.

- If , then we have

The structure of this paper is as follows. In Section 1, we introduce the predictor–corrector method on modified graded meshes for solving Equation (1). Section 2 presents several lemmas for the case , and Section 3 discusses lemmas for the case . In Section 4, we provide proofs of the theorems. Section 5 provides numerical examples demonstrating the consistency between the numerical results and the theoretical predictions.

Throughout the paper, the symbol C denotes a generic constant, which may vary across different occurrences but remains independent of the mesh size.

2. Some Lemmas for

Denote

where P, K, are defined in (4). Then, in (4) can be rewritten as follows:

where , , and J is defined in (4).

Lemma 1.

Proof.

Choose such that, since ,

Note that

which implies that when , we have

Choose

and we see that when ,

Further, we have . In fact, implies that . Hence, with ,

Thus, for , we obtain

The proof of Lemma 1 is complete. □

In the rest of the paper, we assume .

Lemma 2.

Suppose and satisfies Assumption 1. Let .

- 1.

- If , then we have

- 2.

- If , then we have

- 3.

- If , then we have

In the above, denotes a piecewise linear approximation of defined on each interval for ,

Proof.

For , we decompose the integral into three parts,

Using Assumption 1, we have

If , since , we have

If , since and , we obtain

Thus, there exists a constant such that

For , we have

When , by Lemma 1, we obtain

When , we get

For , we have, with and , by Assumption 1,

There exist , such that

For , when , we have

Case 1. . There holds

For , there exists , such that

For , we obtain

For , by Lemma 1, we get

If , we have

If , we have

If , we have

Hence, we obtain, with ,

Case 2. . For , there exists , such that

and

Case 3. . For , there exists , such that

and

Next, we consider with .

Case 1. . For , we have

Note that

We arrive at

Case 2. . We have

We first consider . For , we have

and

Now we turn to . For , we have

and, by Lemma 1,

and

Case 3. . For , we have

and

For , there exist , , such that

Using Assumption 1, we have, with ,

When , by (24) and Lemma 1, we obtain

When , by (17), we arrive at

Thus, for , noting and , we have the following cases.

If , we have

If , we obtain

The remaining cases can be considered similarly. □

The following Lemmas 3 and 4 hold for .

Lemma 3.

Let and . The weights and defined in (7) and (8), respectively, satisfy the following properties:

- 1.

- For all , we have

- 2.

- For all , we have

Proof.

For , it holds that

For , it follows that

For , we have

Hence, we show .

Note that, with ,

Since the is positive over the integration interval, it follows that . □

Lemma 4.

Let . For , we have

where is defined in (6).

Proof.

By (7), we consider two cases:

When , we have

When , we have

The proof of Lemma 4 is complete. □

Lemma 5.

Suppose and satisfies Assumption 1. Let .

- 1.

- If , then we have

- 2.

- If , then we have

- 3.

- If , then we have

Here, denotes a piecewise constant approximation of defined on for ,

Proof.

The following proof is similar to the proof of Lemma 2. Let

For , by Lemma 3 and Assumption 1, we obtain

By (9), it follows that

For , by Lemma 4 and (10), we have

For , by Lemma 4 and (11), we have

For , with , where , we have

By Assumption 1, we get,

For , we consider the following three cases:

Case 1. . We have

For , we have

Thus, with and , by (20), we get

Case 2. . We have

For (with ), we have

For (with ), by Lemma 1, we have

Case 3. . For (with ), we have

For , for , by Assumption 1, there exists , such that

When , by Lemma 4, Lemma 1, and , we have

When , by Lemma 4, we have

Thus, when , for , if , we have

If , we have

If , we have

The remaining cases can be proven similarly. This completes the proof of Lemma 5. □

We remark that, in the proof of Lemma 5, some inequalities hold for . The following Lemma 6 holds for .

Lemma 6.

Let , then there exists a constant such that the following inequalities hold,

where and are weights defined by (5) and (6), for .

Proof.

We will prove inequality (35), while the proof of (34) follows analogously.

where denotes the remainder term. By setting in the integral, we have

From Lemma 3, . Therefore, inequality (35) holds. □

3. Some Lemmas for the Case

Lemma 7.

Suppose and satisfies Assumption 1. Let .

- 1.

- If , then we have

- 2.

- If , then we have

- 3.

- If , then we have

Proof.

For , we decompose the integral into three parts,

If , we have

When , since , we obtain

When , we have

For , by Lemma 2, we have

For , we only consider , as has already been discussed in Lemma 2.

Case 1. . We have

By (12) and , we have

By (13), Lemma 1, and , we have

Case 2. . By (15) and , we have

Case 3. . By (17), we have

The cases of and have also been discussed in Lemma 2.

For , if , when , we have

Similarly, the cases and can be considered. Other cases can also be considered in the same way. □

Lemma 8.

Suppose and satisfies Assumption 1. Let .

- 1.

- If , then we have

- 2.

- If , then we have

- 3.

- If , then we have

Proof.

The following proof is similar to the proof of Lemma 7. Note that

By Lemma 5, we get

When , by Lemma 4, we have

When , by Lemma 4, we have

For , by Lemma 5, with , where , we have

By Assumption 1, we get

Case 1. . We have

By Lemma 4 and (12), we have

By Lemma 4, (13), and Lemma 1, we have

Case 2. . By Lemma 4 and (15), we have

Case 3. . By Lemma 4 and (17), we have

The cases of and have also been discussed in Lemma 5.

Thus, for , since , , we have

The remaining cases can be considered similarly. □

4. Proofs of Theorems 1 and 2

We first prove Theorem 1.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Subtracting (3) from (6), we get

The first term, , can be estimated using Lemma 2. For the second term, , by Lemma 3 and the Lipschitz condition of g, we have

For the third term, , applying Lemma 3 and the Lipschitz condition of g, we have

Note that

We obtain

The term can be estimated using Lemma 5. For , applying Lemmas 3 and 4, we have

Combining the estimates of , , , and , we obtain

Next, we prove the theorem using mathematical induction. We begin by considering the case .

Case 1. . We discuss the case when . Suppose there exists a constant such that, for and , the following inequality holds:

We aim to prove that

Using Lemmas 2 and 5, we have

Substituting the assumption into the inequality, we get

Following the proof strategy in [1], we first choose T sufficiently small such that the second term on the right-hand side in (39) is less than . Then, we select N sufficiently large and sufficiently large so that the sum of the remaining three terms on the right-hand side is also less than . Thus, we have

For the case when , a similar argument yields

Case 2. . Let Assume that

Using similar steps to Case 1, we obtain

For the case when , a similar argument yields

Case 3. , similar to the proof of Theorem 1.4 in [26]. □

We now turn to the proof of Theorem 2.

Proof of Theorem 2.

In the case of , similar to the proof of Theorem 1, we consider the following three cases:

Case 1. . Let Assume that

Using Lemma 7 and Lemma 8, we have

Following the proof strategy in [1], we first choose T sufficiently small such that the second term on the right-hand side in (40) is less than . Then, we select N sufficiently large and sufficiently large so that the sum of the remaining three terms on the right-hand side is also less than . Thus, we have

Case 2. . Assume that

Using similar steps to Case 1, we obtain

Case 3. , similar to the proof of Theorem 1.4 in [26]. □

5. Numerical Simulations

In this section, we will consider some numerical examples to illustrate the convergence orders of the proposed numerical method (6) under different smoothness conditions of . We focus on the case for . Similarly, we can consider the case for .

Let N be a positive integer. Let be the partition of . For the graded mesh, we choose , with . When , this mesh is the uniform mesh. For the modified mesh, we have for and for .

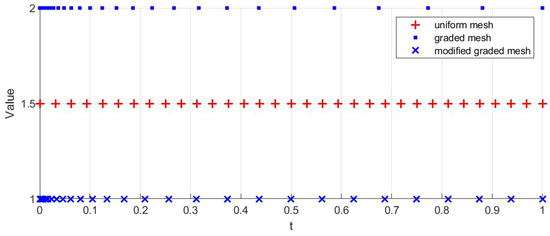

In Figure 1, we choose and and plot the graded mesh with and uniform mesh with and the modified mesh with , and with . The modified graded mesh is uneven from to , and uniform from to .

Figure 1.

Three kinds of temporal mesh partitions.

Example 1.

Consider the following fractional differential equation,

subject to the initial condition

where , , and , , and the exact solution is . Here, , which implies that the regularity of behaves as , which satisfies Assumption 1.

Assume that and , are the solutions of (3) and (6), respectively. By Theorem 1 with , we have the following error estimate (note that ):

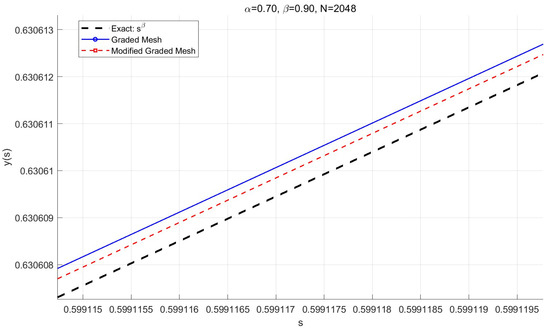

When , , , and , we compare the exact solution and the numerical solutions for the graded mesh and the modified graded mesh . Figure 2 shows the exact solution along with the numerical solutions obtained using the graded mesh and the modified graded mesh. From the figure, it is evident that both methods approximate the exact solution well, but the modified graded mesh achieves a smaller error compared to the graded mesh. In our numerical tests, we see that the errors from the modified graded mesh depend on the value of K.

Figure 2.

The exact solution and the numerical solutions.

For the different values of , we select the appropriate values of r and set , where Then, we compute the maximum nodal error (as previously defined) for various N and determine the experimental order of convergence (EOC) using the following formula:

In Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, we set and present the experimental order of convergence (EOC) alongside the maximum nodal errors for different values of N. The numerical results indicate that the error of the modified mesh is smaller than that of the graded mesh.

Table 1.

Maximum errors at the grid points and convergence rates for Example 1 with parameters , , , at .

Table 2.

Maximum errors at the grid points and convergence rates for Example 1 with parameters , , , , and .

Table 3.

Maximum errors at the grid points and convergence rates for Example 1 with parameters , , , , and .

Example 2.

Consider the following

where and . The exact solution , where is the Mittag-Leffler function defined by

Hence,

which suggests that the regularity of behaves as , where .

According to Theorem 1, when , the error estimate is given by

Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 summarize the experimental order of convergence (EOC) along with the maximum nodal errors for different values of N. The observed EOC closely aligns with the theoretical prediction: .

Table 4.

Maximum errors at the grid points and convergence rates for Example 2 with parameters , , , and .

Table 5.

Maximum errors at the grid points and convergence rates for Example 2 with parameters , , , and .

Table 6.

Maximum errors at the grid points and convergence rates for Example 2 with parameters , , , and .

Through the analysis and numerical experiments, it is clear that the modified graded mesh achieves smaller errors compared to the graded mesh. The traditional graded mesh, with its non-uniform step size, is effective at addressing the weak singularity near the initial time . However, as the time nodes move further away from the initial point, the sparsity of the mesh can lead to significant errors. In contrast, the modified graded mesh adopts the graded mesh near to better handle the singularity and transitions to a uniform mesh in later regions, effectively reducing the overall error.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a modified graded mesh Adams-type predictor–corrector method is proposed for solving fractional differential equations. The traditional graded mesh works well near the initial time because of its non-uniform step sizes, which handle the weak singularity effectively. However, as the time nodes move away from the initial point, the mesh becomes sparse, leading to larger errors. On the other hand, the modified graded mesh uses a graded mesh near to better handle the singularity and switches to a uniform mesh in areas farther from the initial point, significantly reducing the overall error. Numerical experiments further confirm that the modified graded mesh method outperforms the traditional graded mesh in terms of accuracy. This makes the improved Adams-type predictor–corrector method an efficient tool for solving fractional differential equations.

In recent years, some new fractional definitions have been developed, providing new perspectives and tools for the numerical solution of fractional differential equations. Future research directions include extending this method to Caputo–Hadamard fractional derivatives and other fractional definitions (see [27]). We plan to explore numerical methods under these new definitions in future work to further enhance the applicability and accuracy of the proposed approach.

Author Contributions

We have both contributed equal amounts towards this paper. Y.Y. (Yuhui Yang) conducted the theoretical analysis, wrote the original draft, and carried out the numerical simulations. Y.Y. (Yubin Yan) introduced and provided guidance in this research area. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Reviewers and the Associate Editor for their helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Appendix A

The weights in (5) satisfy the following:

Case 1. . For , we have

Case 2. . For , we have

Case 3. .

Case 4. .

The weights in (6) satisfy

For (), the weights satisfy the following:

Case 1. .

Case 2. .

Case 3. .

Case 4. .

For , the weight is given by

References

- Diethelm, K.; Ford, N.J.; Freed, A.D. Detailed error analysis for a fractional Adams method. Numer. Algorithms 2004, 36, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diethelm, K. The Analysis of Fractional Differential Equations; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, B.; Lazarov, R.; Zhou, Z. Numerical methods for time-fractional evolution equations with nonsmooth data: A concise overview. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2019, 346, 332–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Stynes, M. Error analysis of a second-order method on fitted meshes for a time-fractional diffusion problem. J. Sci. Comput. 2019, 79, 624–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopteva, N.; Meng, X. Error analysis for a fractional-derivative parabolic problem on quasi-graded meshes using barrier functions. Siam J. Numer. Anal. 2020, 58, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stynes, M.; O’Riordan, E.; Gracia, J.L. Error analysis of a finite difference method on graded meshes for a time-fractional diffusion equation. Siam J. Numer. Anal. 2017, 55, 1057–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. Implicit-explicit difference schemes for nonlinear fractional differential equations with nonsmooth solutions. Siam J. Sci. Comput. 2016, 38, A3070–A3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yi, Q.; Chen, A. Finite difference methods with non-uniform meshes for nonlinear fractional differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2016, 316, 614–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Roberts, J.; Yan, Y. A note on finite difference methods for nonlinear fractional differential equations with non-uniform meshes. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2018, 95, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubich, C. Fractional linear multistep methods for Abel-Volterra integral equations of the second kind. Math. Comput. 1985, 45, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Suzuki, J.L.; Zhang, C.; Zayernouri, M. Implicit-explicit time integration of nonlinear fractional differential equations. Appl. Numer. Math. 2020, 156, 555–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Xu, C. A high-order scheme for the numerical solution of fractional ordinary differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2013, 238, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedas, A.; Tamme, E. Numerical solution of nonlinear fractional differential equations by spline collocation methods. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2014, 255, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inc, M. The approximate and exact solutions of the space-and time-fractional Burgers equations with initial conditions by variational iteration method. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2008, 345, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, H.; Daftardar-Gejji, V. Solving linear and nonlinear fractional diffusion and wave equations by Adomian decomposition. Appl. Math. Comput. 2006, 180, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Lazarov, R.; Pasciak, J.; Zhou, Z. Error analysis of a finite element method for the space-fractional parabolic equation. Siam J. Numer. Anal. 2014, 52, 2272–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayernouri, M.; Karniadakis, G.E. Discontinuous spectral element methods for time- and space-fractional advection equations. Siam J. Sci. Comput. 2014, 36, B684–B707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W. Short memory principle and a predictor-corrector approach for fractional differential equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2007, 206, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Jang, B. A high-order predictor-corrector method for solving nonlinear differential equations of fractional order. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2017, 20, 447–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, C.; Stynes, M. A fast second-order predictor-corrector method for a nonlinear time-fractional Benjamin-Bona–Mahony-Burgers equation. Numer. Algorithms 2024, 95, 693–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Jang, B. A fast and high-order numerical method for nonlinear fractional-order differential equations with non-singular kernel. Appl. Numer. Math. 2021, 163, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarnezhad, F. A high-order predictor-corrector method with non-uniform meshes for fractional differential equations. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2024, 27, 2577–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diethelm, K.; Ford, N.J. Analysis of fractional differential equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2002, 265, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diethelm, K.; Freed, A.D. The FracPECE subroutine for the numerical solution of differential equations of fractional order. In Forschung und Wissenschaftliches Rechnen 1998; Heinzel, S., Plesser, T., Eds.; Gesellschaft für Wissenschaftliche Datenverarbeitung: Göttingen, Germany, 1999; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Diethelm, K.; Ford, N.J.; Freed, A.D. A predictor-corrector approach for the numerical solution of fractional differential equations. Nonlinear Dyn. 2002, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Roberts, J.; Yan, Y. Detailed error analysis for a fractional Adams method with graded meshes. Numer. Algorithms 2017, 78, 1195–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeka, L.; Baleanu, D.; Abdo, M.S.; Shatanawi, W. Introducing novel Θ-fractional operators: Advances in fractional calculus. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2024, 36, 103352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y. Error analysis of a finite difference scheme on a modified graded mesh for a time-fractional diffusion equation. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 209, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).