Abstract

In computer science and graph theory, prism and antiprism graphs are crucial for network modeling, optimization, and network connectivity comprehension. Applications such as social network analysis, fault-tolerant circuit design, and parallel and distributed computing all make use of them. Their structured nature makes them important, since it offers a framework for researching intricate characteristics, including resilient design, communication patterns, and network efficiency. This work uses the electrically equivalent transformations technique to compute the explicit formulas for the number of spanning trees of three novel families of graphs that have been produced using triangular prisms with their distinctive iteration feature. Additionally, the relationship between these graphs’ average degree and entropy is examined and contrasted with the entropy of additional graphs that share the same average degree as these previously studied graphs.

Keywords:

number of spanning trees; electrically equivalent transformations; triangular prism; entropy MSC:

97K30; 05C63; 05C30

1. Introduction

A subgraph of a connected, undirected graph with vertices that contains all the vertices and edges without creating any cycles is called a spanning tree. The number of spanning trees in graph , denoted by , is also referred to as the complexity of [1]. This is an important and well-studied quantity with a wide range of applications. Listing specific chemical isomers [2], counting the number of Eulerian circuits in a graph [3], solving computationally difficult problems like the wandering salesman and Steiner tree problems [4], and deriving formulas for different graph types can be helpful in figuring out which graphs have the most spanning trees and are the most notable application domains.

Spanning trees are used in network reliability to evaluate a network’s performance, improve its fault resistance, and understand its structure. They form the foundation for protocols like the Spanning Tree Protocol (STP), which provide redundancy, prevent network loops, and determine how to add new links for optimal reliability [5].

A traditional Kirchhoff matrix from 1847 can be used to determine the number of spanning trees for a connected graph with vertices [6]. The Kirchhoff matrix is an characteristic matrix , where is the adjacency matrix of and is the diagonal matrix of the degrees of , such that , defined as follows:

Each co-factor of corresponds to the number of spanning trees in a graph .

Another way to determine the number of spanning trees is to assume that the eigenvalues of the Kirchhoff matrix of a graph with vertices are .

In 1974, Kelmans and Chelnokov [7] demonstrated the following:

This method has been used to calculate the number of spanning trees of cartesian and composition products of two graphs [8].

The deletion–contraction strategy is a popular technique for determining the number of spanning trees . The number of spanning trees in a multigraph can be reliably determined using this method. This method uses the following formula:

where is the graph that results from removing an arbitrary edge and is the graph that results from contracting an arbitrary edge [9].

1.1. Electrically Equivalent Transformations

The technique of reducing a complicated electrical circuit to a simpler, equivalent one without altering its overall electrical behavior is known as electrical equivalent transformation. Kirchhoff was inspired by the study of graph theory, which concerns the possibility of representing an electrical network as a graph with edge weights corresponding to connectivity.

The ratio of weighted spanning trees to weighted thickets, where a thicket is a particular kind of spanning forest, can be used to determine the effective conductance between two vertices and [10]. That is the effect conductance between two vertices and , which can be expressed as the quotient of the (weighted) number of spanning trees and the (weighted) number of thickets.

We list the impact of a few basic modifications on the quantity of spanning trees below.

Let represent the weighted number of spanning trees and let be the associated electrically equivalent graph. Let be the weighted number of spanning trees of and be the weighted number of spanning trees of .

- Parallel edges: When two parallel edges in with conductances and are joined to form a single edge in with a conductance of , the number of spanning trees in , , remains equal to .

- Serial edges: If two serial edges in with conductances and are linked to generate a single edge in with a conductance of , the number of spanning trees in , , can be calculated as multiplied by .

- Δ-Y Transformation: When a triangle in with conductances , and is transformed into an electrically equivalent star graph in with conductances , and , the number of spanning trees in , , can be computed as multiplied by .

- Y-Δ Transformation: One may obtain the number of spanning trees in , , by multiplying by , when an electrically equivalent triangle in with conductances and is created from a star graph in with conductances , and .

This method has been used to calculate the number of spanning trees in specific graph sequences generated by a Johnson skeleton graph [11]. Johnson graph 63, also known as the six-tetrahedral graph, is a highly symmetric graph with unique properties that make it a subject of interest in graph theory and related fields.

The “63 Johnson skeleton graph” is a particular example of a graph from the larger family of Johnson graphs, which are defined by subsets and intersections rather than by the structure of a polyhedron.

1.2. Some Types of Triangular Prism Graphs

The constant goal in mathematics is to create a new structure from an old one. This is also true for graphs, where a given set of graphs can be used to construct a huge number of new graphs.

We will begin by introducing three new categories of triangular prism graphs. The number of trees that extend into each of the three augmented families that these three graphs establish will then be determined, along with their entropy, in the next section.

The triangular prism graph’s use as a model for technical and physical systems, including those in network science, engineering, and optics, makes it significant. It illustrates the dispersion of light principles in optics. In engineering, it depicts the stable triangular construction utilized in building frames and bridges. The triangular prism graph is used in graph theory and network research to examine the intricacy of structures and network characteristics like connection and signal transmission.

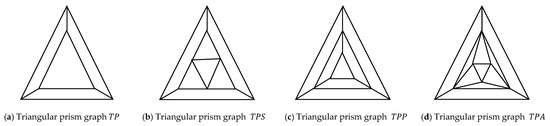

In this work, we use the electrically equivalent transformations to determine the number of spanning trees for three new graph families based on a triangular prism graph, or , as illustrated below in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Triangular prism graphs , , and .

- (1)

- The triangular prism graph, or , is a graph that is made by substituting a star -gon graph for the middle triangle of a triangular prism, . See Figure 1b.

- (2)

- The triangular prism graph, or , is a graph that is made by substituting another triangular prism for the middle triangle of a triangular prism, . See Figure 1c.

- (3)

- The triangular prism graph, or , is a graph that is made by substituting a triangular antiprism graph for the middle triangle of a triangular prism, . See Figure 1d.

A triangular prism graph is a graph that depicts the vertices and edges of a three-dimensional triangle prism. On the other hand, a Johnson graph is a family of graphs made from set systems in which the edges join subsets of a given size and the vertices are subsets of a particular size. Their origins are crucially different: a Johnson graph is defined algebraically from combinations of sets, while a triangular prism graph is directly based on geometric geometry.

2. Main Results

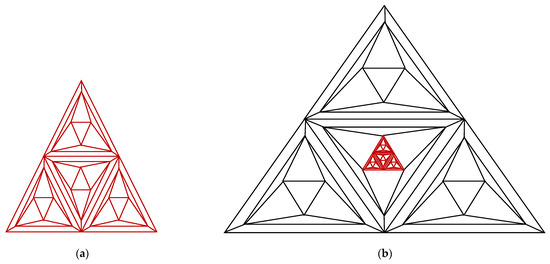

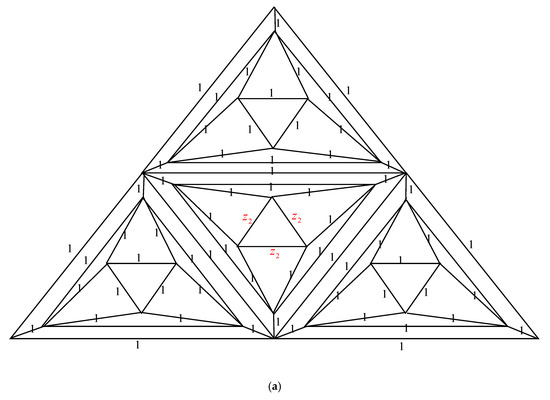

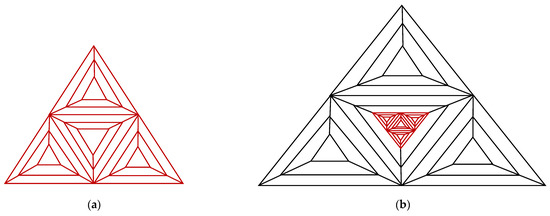

2.1. Complexity of the Graph Family Generated by Triangular Prism Graph,

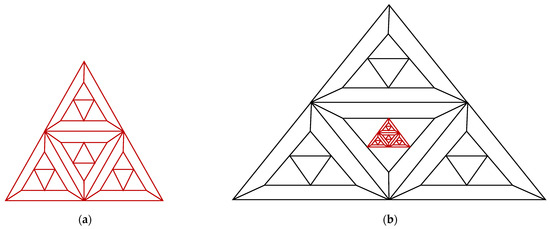

The graph family generated by the triangular prism graph and denoted by is a recursive definition using the graphs and (triangle or ): a replica of is used in place of the middle triangle of to create the graph . The middle triangle in the graph is typically swapped out for to make , as shown in Figure 2. and are the total vertices and edges of , respectively. According to this architecture in the large limit, the average degree of is .

Figure 2.

(a) The graph . (b) The graph .

Theorem 1.

For , the number of spanning trees in the graph family, , generated by the triangular prism graph, , is given by the following:

where ,

, ,

, and .

Proof.

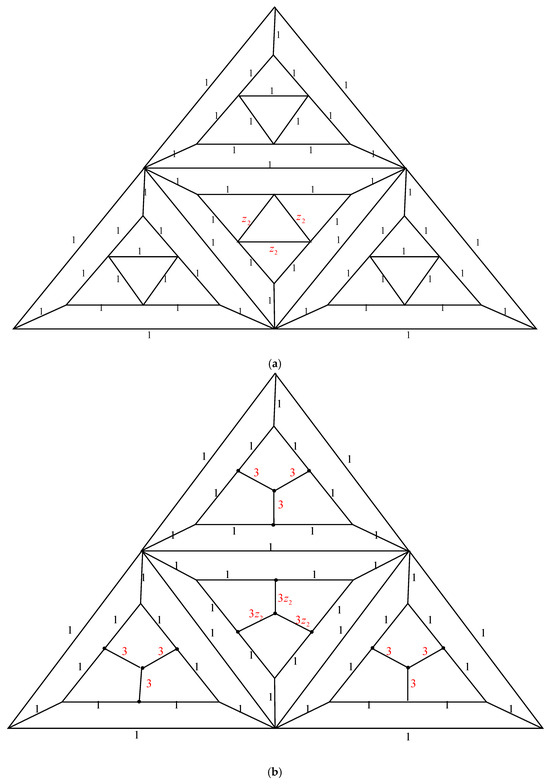

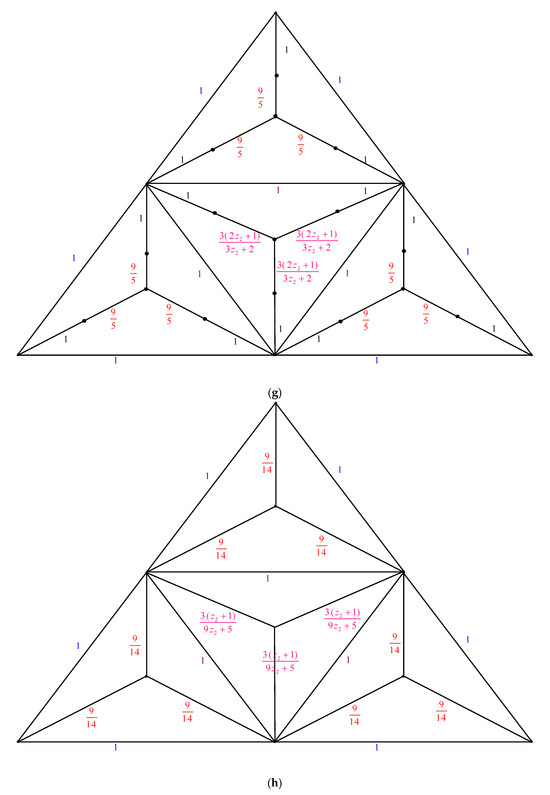

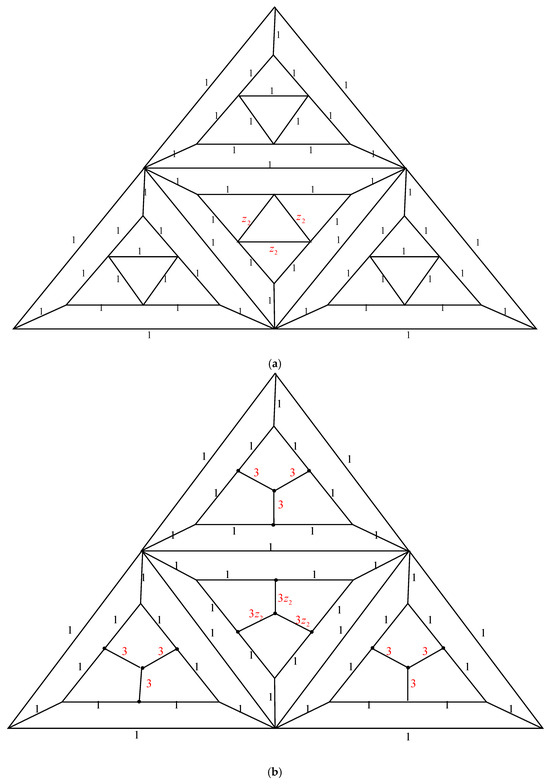

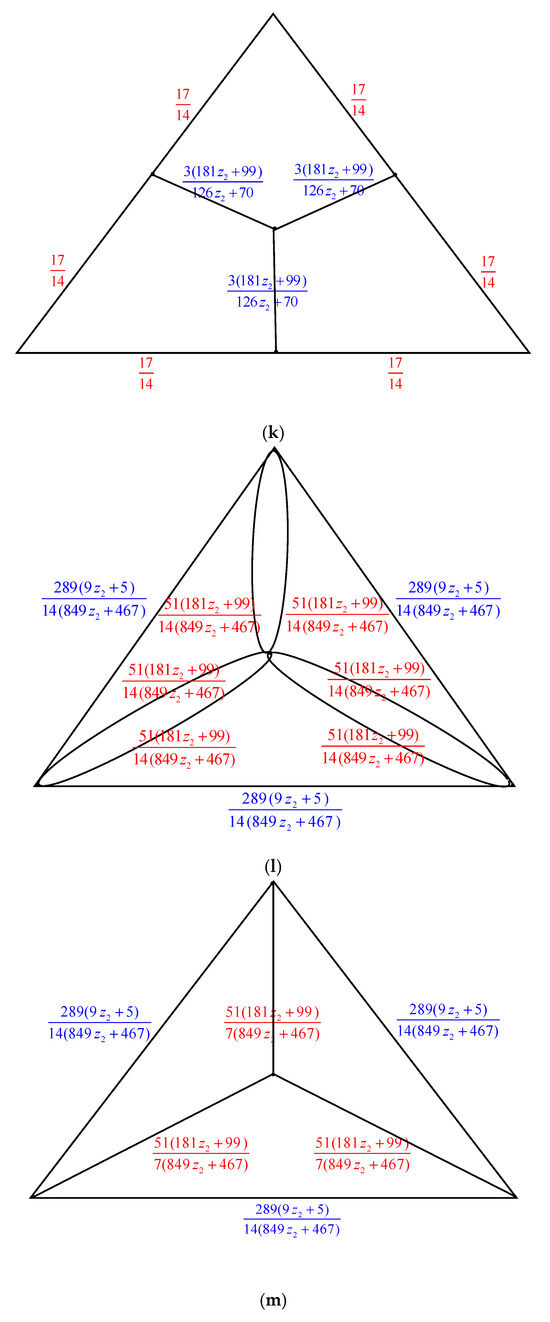

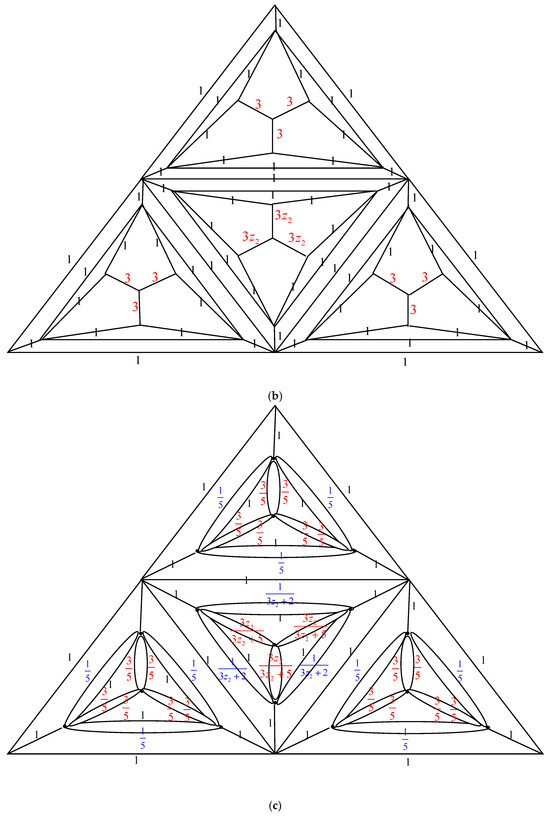

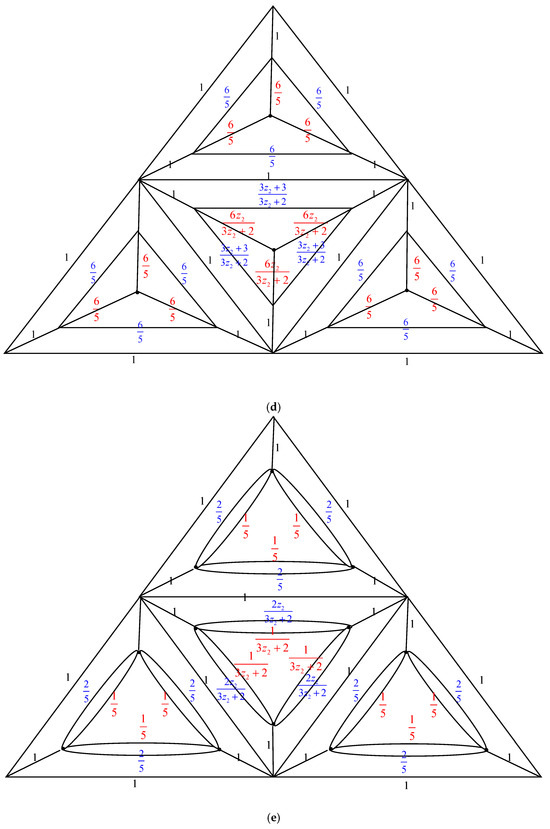

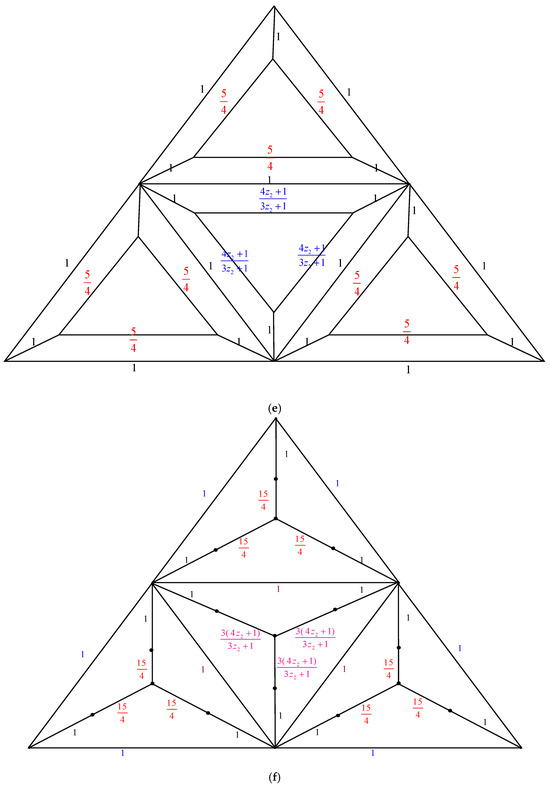

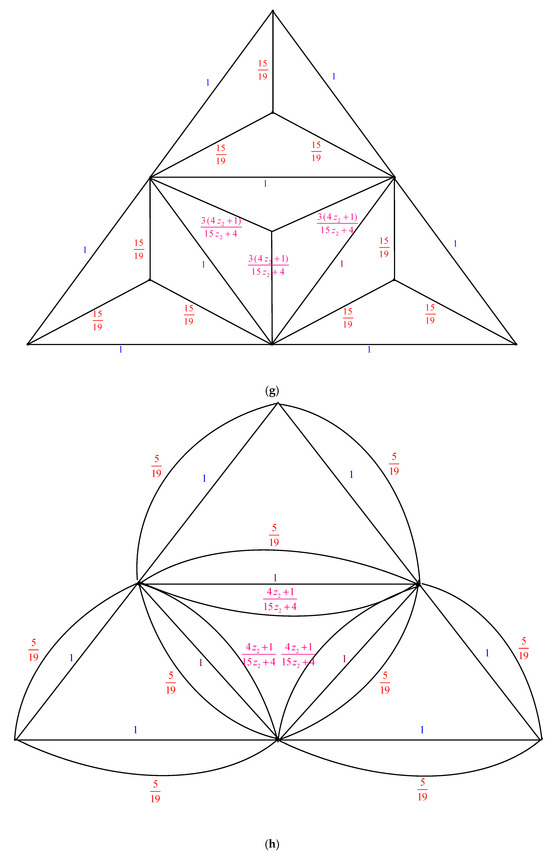

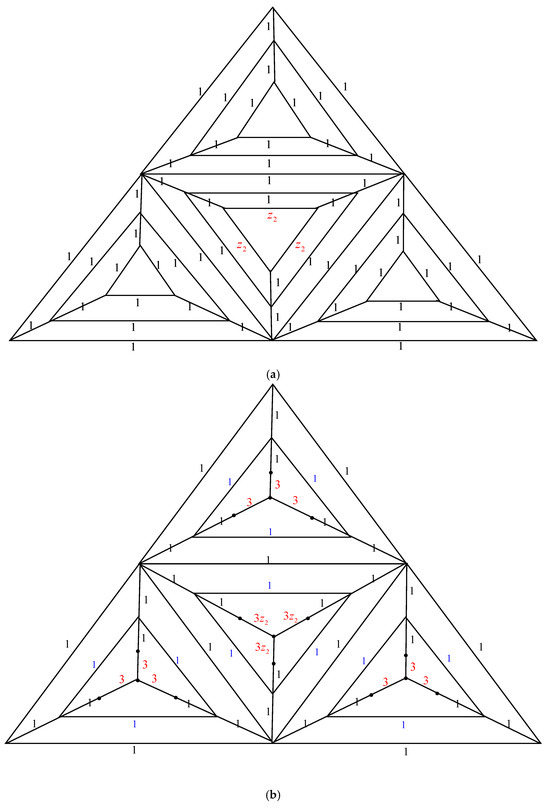

The electrically equivalent transformation is used to convert to . The process of transforming into is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The transformations from to . (a) The graph . Utilizing the Δ-Y Transformation method, we obtain . (b) The graph . The Y-Δ Transformation technique is used to obtain (c) The graph . The parallel edge rule is used to obtain (d) The graph . Utilizing the Y-Δ Transformation method, we obtain (e) The graph . By applying the parallel edge rule, we obtain (f) The graph . The Δ-Y Transformation method gives us (g) The graph . By applying the Y-Δ Transformation method, we obtain (h) The graph . The serial edge rule is used to obtain (i) The graph . Applying the rule of parallel edges, we arrive at (j) The graph . The Δ-Y Transformation rule gives us (k) The graph . The Y-Δ Transformation rule gives us (l) The graph . When we use the parallel edge rule, we obtain (m) The graph . Applying the Y-Δ Transformation rule, we obtain . (n) The graph . The parallel edge rule is applied, and we obtain (o) The graph .

The result of combining these fourteen transformations is the following:

Thus, we have

Moreover,

where

Its characteristic equation is with the following roots:

These two roots can be subtracted from both sides of to obtain the following:

Let , then

Then, by Equations (5) and (6), we obtain the following:

Therefore,

From the expression , we have the following:

Then,

Therefore,

If , we obtain the following:

Thus, we obtain the following:

With the expression and the coefficients of and , represented as and , respectively, we obtain the following:

So, we obtain the following:

Using the expression with Equations (8) and (9), we obtain the following:

Equation (11) has the characteristic equation , with the roots and .

The general solutions of Equation (11) are .

Using the initial conditions and yields the following:

If , is devoid of any electrically equivalent transformation. By entering Equation (12) into Equation (10), we obtain the following:

Equation (13) is satisfied for , and . Thus, the number of spanning trees in the graph family generated by triangular prism graph is determined by the following:

By substituting Equation (7) into Equation (14), we achieve the intended outcome. □

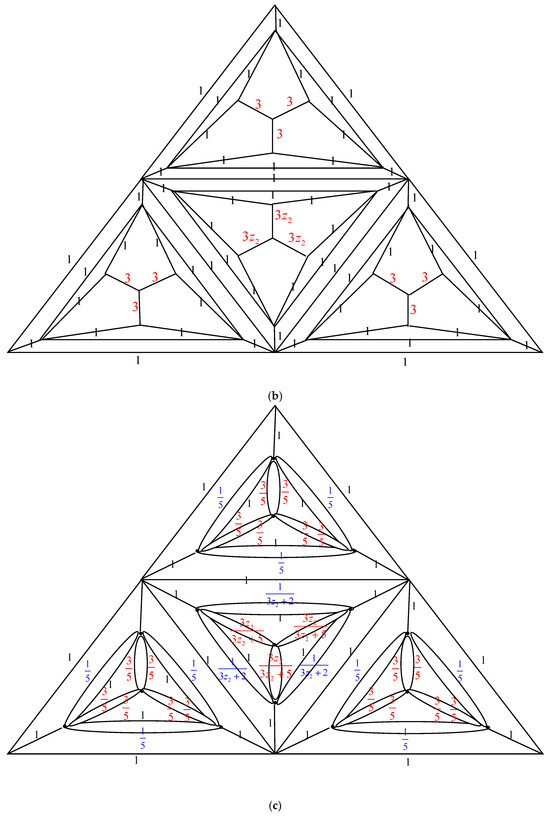

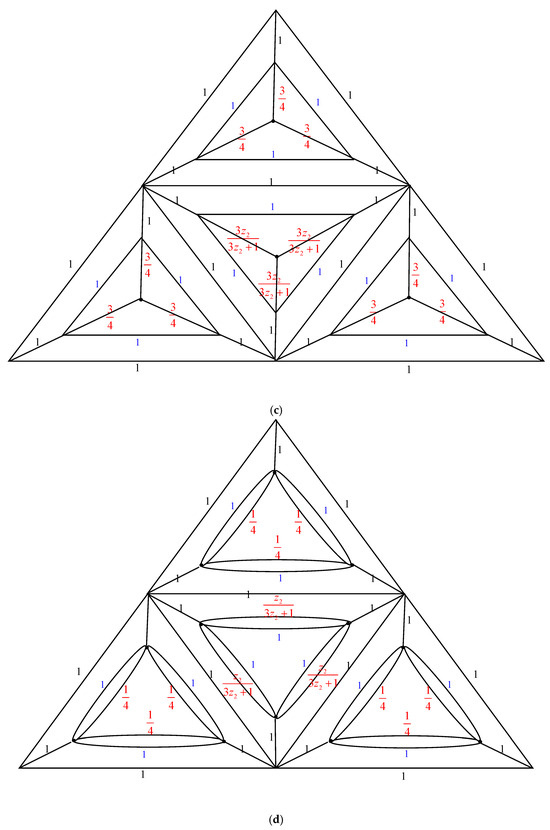

2.2. Complexity of the Graph Family Generated by Triangular Prism Graph,

The graph family generated by triangular prism graph and denoted by is a recursive definition using the graphs and (triangle or ): a replica of is used in place of the middle triangle of to create the graph . The middle triangle in the graph is typically swapped out for to make , as shown in Figure 4. and are the total vertices and edges of , respectively. According to this architecture in the large limit, the average degree of is .

Figure 4.

(a) The graph . (b) The graph .

Theorem 2.

For , the number of spanning trees in the graph family, generated by the triangular prism graph is given by the following:

where

Proof.

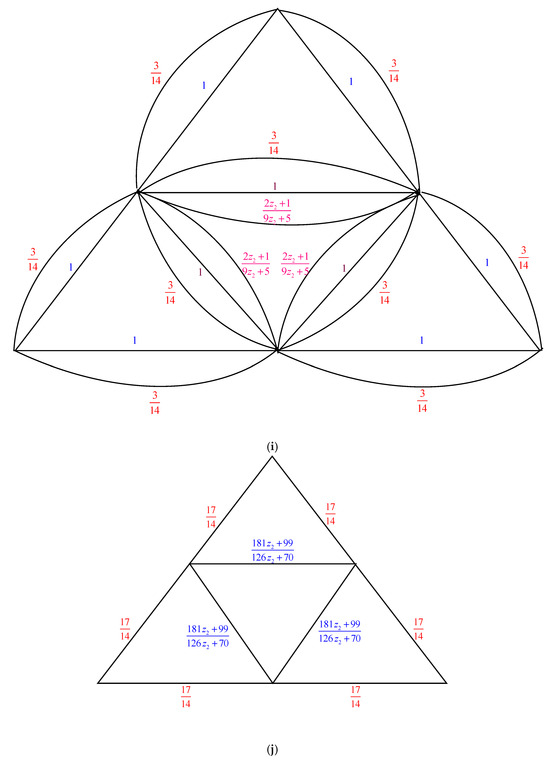

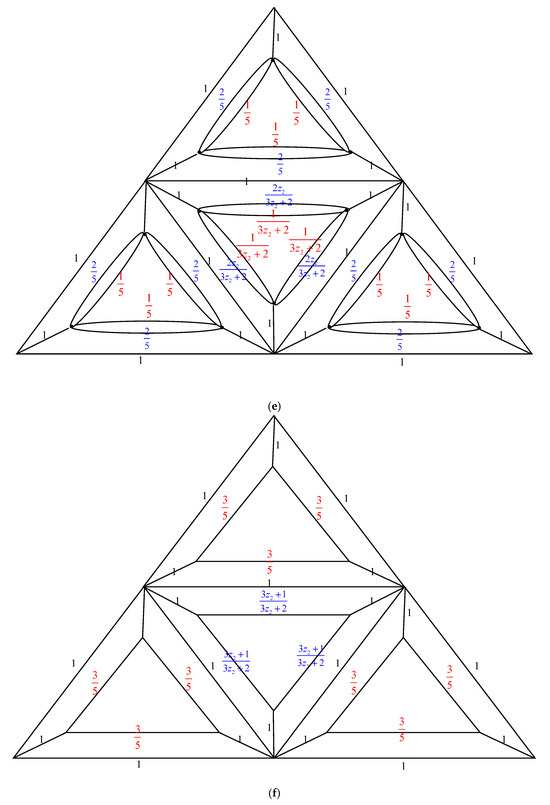

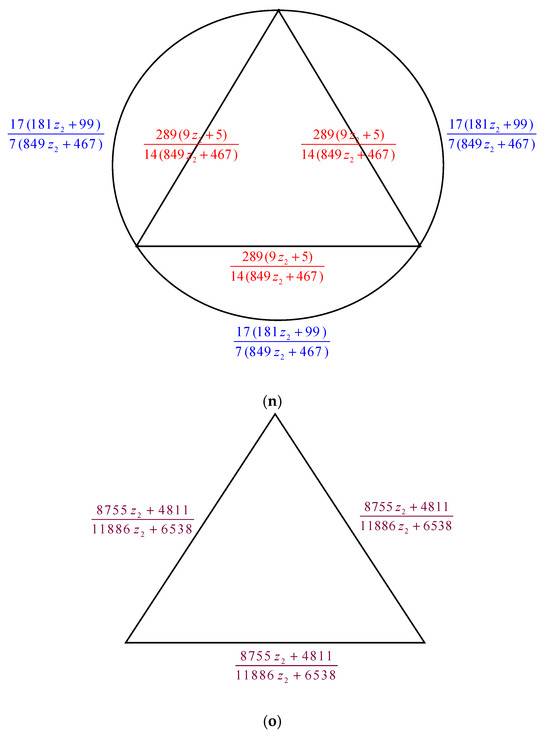

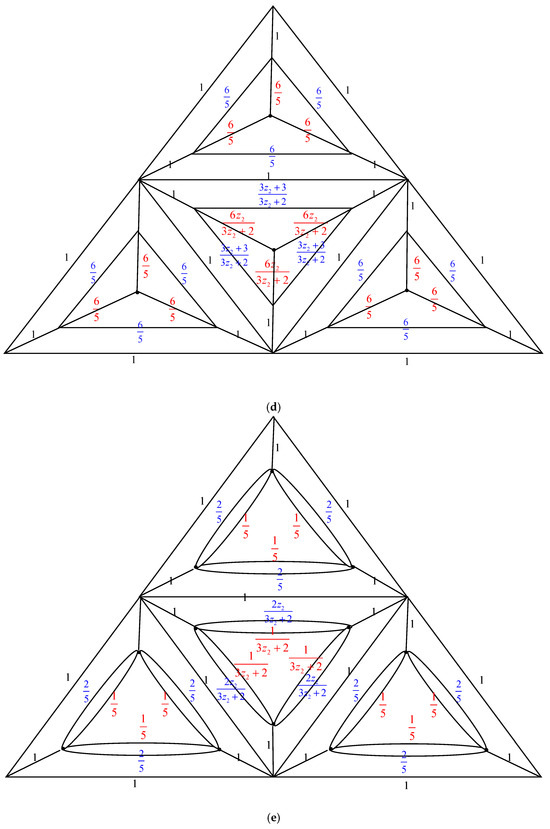

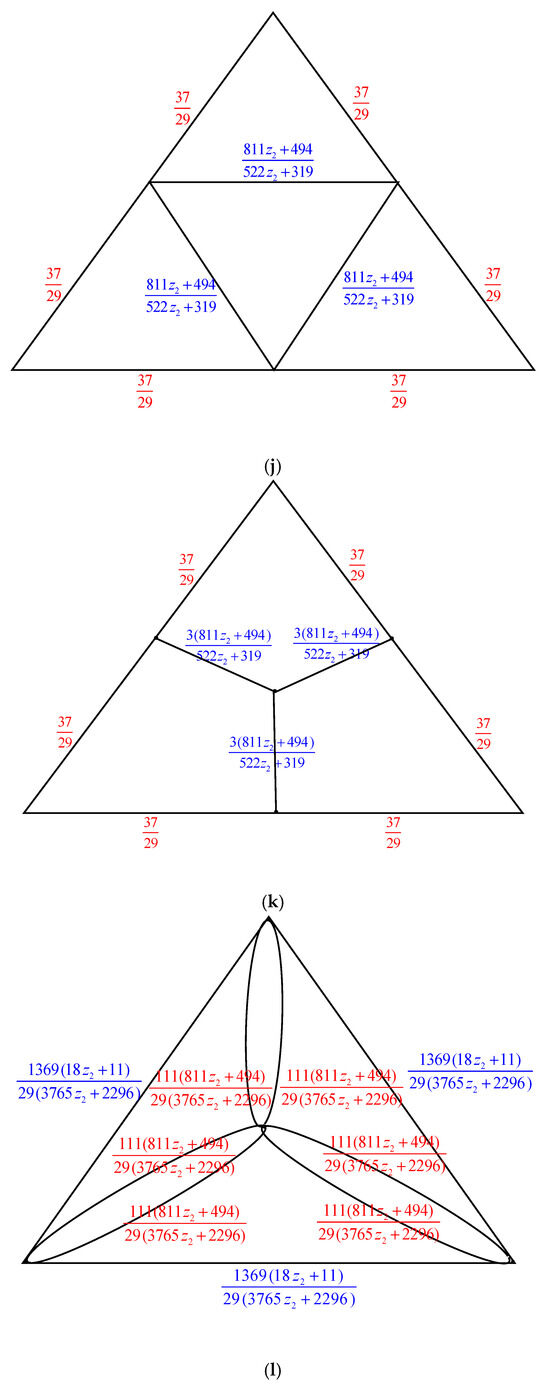

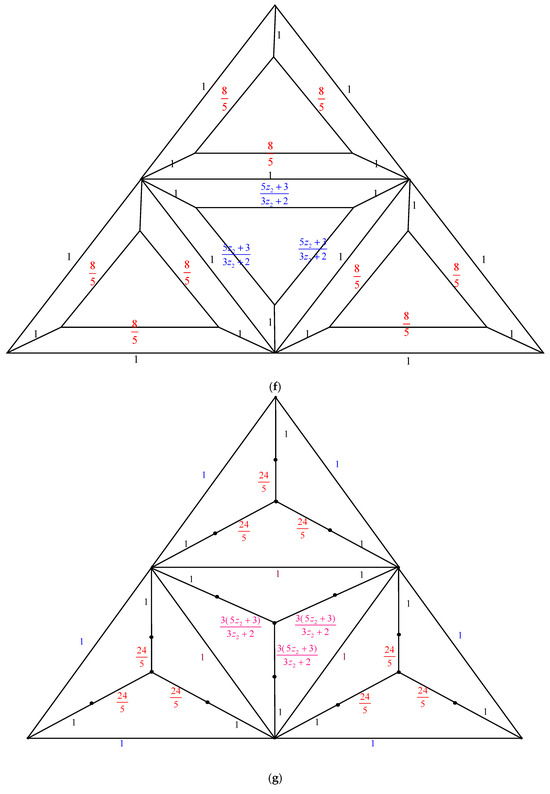

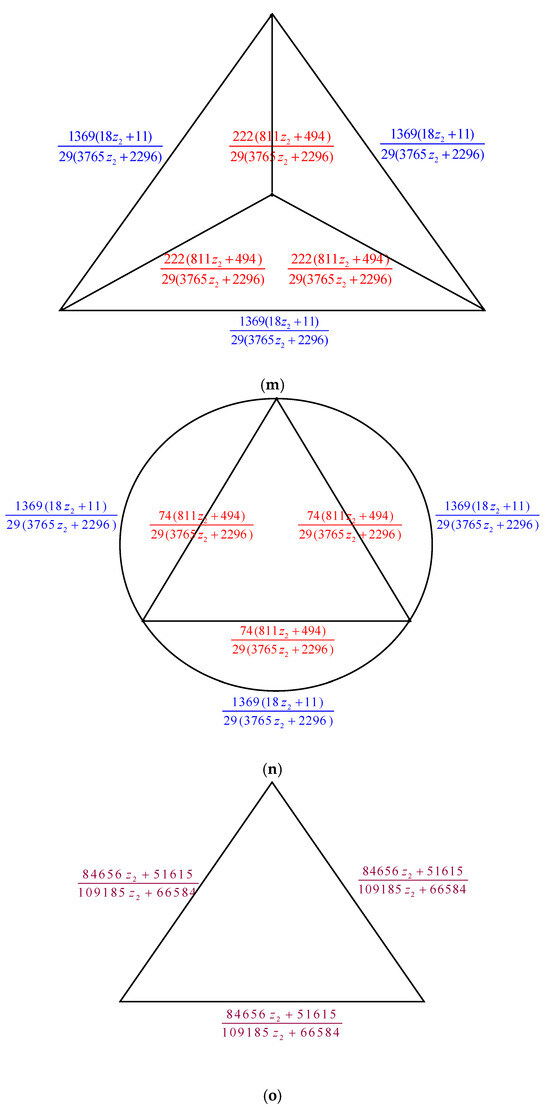

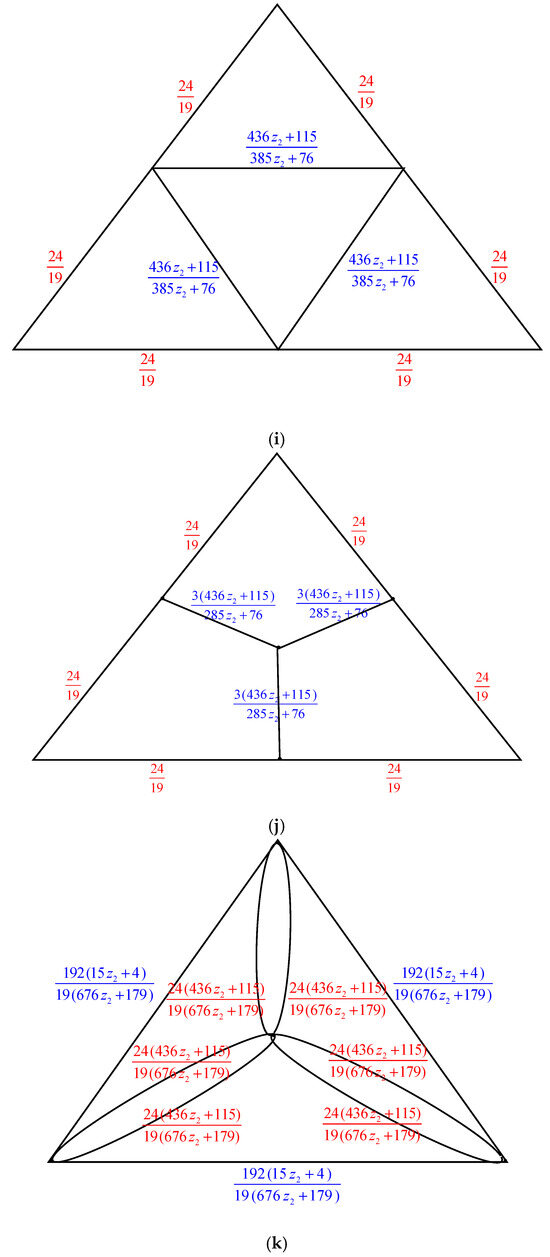

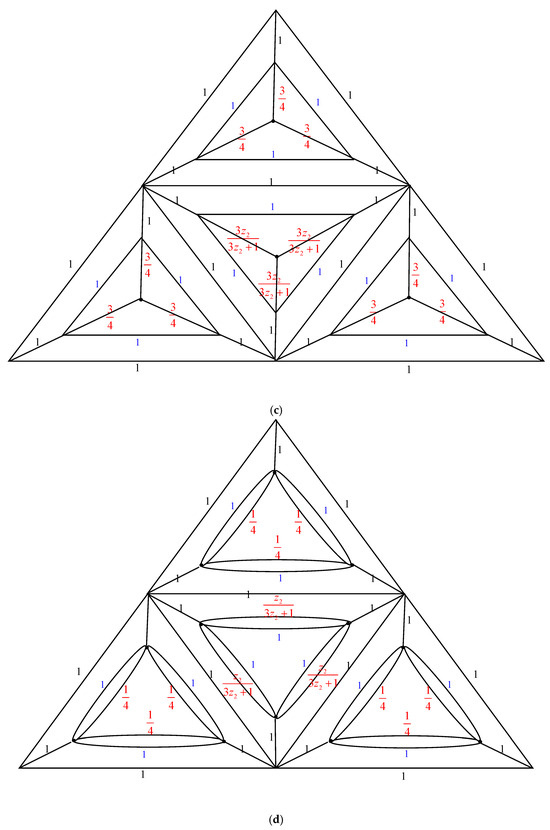

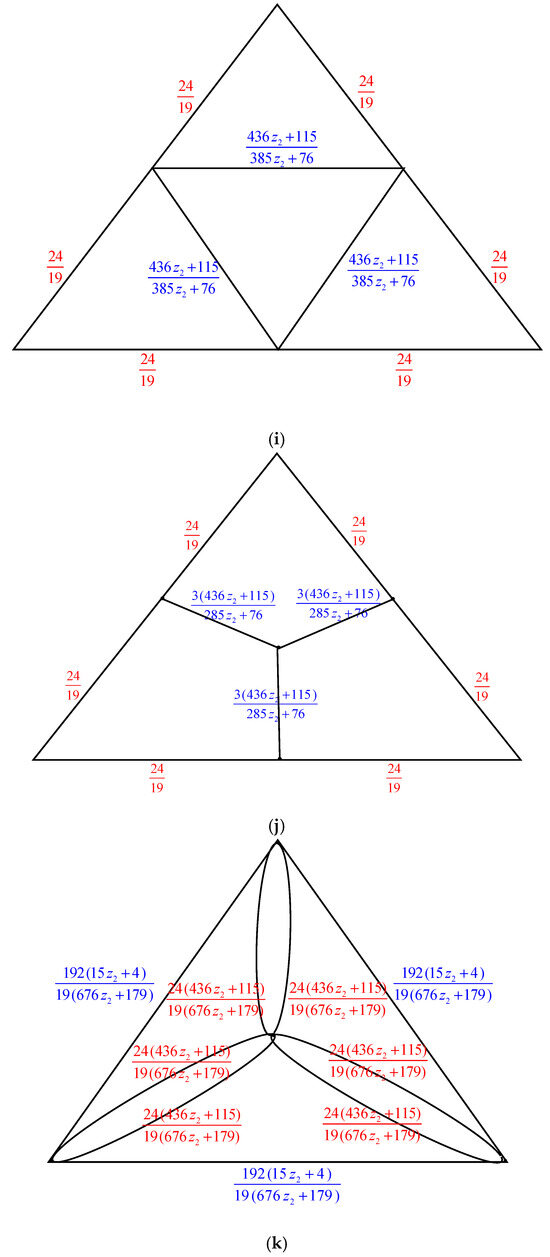

The electrically equivalent transformation is used to convert the graph to the graph . The process of transforming the graph into the graph is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The transformations from to . (a) The graph . Using the Δ-Y Transformation technique, we obtain (b) The graph . Applying the Y-Δ Transformation rule yields (c) The graph . The parallel edge rule is applied, and the result is (d) The graph . We obtain the following by using the Y-Δ Transformation rule: . (e) The graph . The parallel edge rule is applied, and the result is (f) The graph . From the Δ-Y Transformation rule, we obtain (g) The graph . The serial edge rule is applied, and the result is (h) The graph . When we apply the Y-Δ Transformation rule, we obtain (i) The graph . The parallel edge rule is used to obtain (j) The graph . By applying the Δ-Y Transformation rule, we obtain (k) The graph . The Y-Δ Transformation rule gives us (l) The graph . By utilizing the parallel edge rule, we arrive at (m) The graph . Applying the Y-Δ Transformation rule, we obtain (n) The graph . The parallel edge rule is applied, and we obtain . (o) The graph .

These fourteen transformations are combined to produce the following:

Thus, we have the following:

Furthermore,

where

Its characteristic equation is , having the following roots:

When we subtract these two roots from each side of , we obtain the following:

Let ; then, .

Then, using Equations (17) and (18), we obtain the following:

Therefore,

From the expression , we have the following:

Then,

Therefore,

If , we obtain the following:

Thus, we obtain the following:

Utilizing the expression and designating and as the coefficients of and , we obtain the following:

Thus, we obtain the following:

Utilizing Equations (20) and (21) and the expression , we obtain the following:

Its characteristic equation is , with the following roots:

Equation (23) has general solutions that are .

Using the initial conditions and , we obtain the following:

If , then has no electrically equivalent transformation. By entering Equation (24) into Equation (23), we obtain the following:

When , Equation (25) is satisfied, since . Consequently, the number of spanning trees in the graph family generated by triangular prism graph is determined by the following:

Equation (19) can be inserted into Equation (26), yielding the desired outcome. □

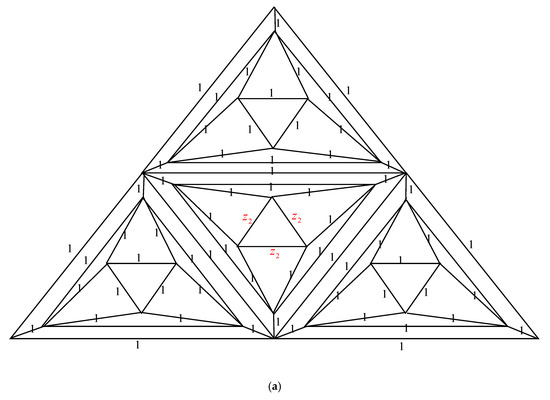

2.3. Complexity of the Graph Family Generated Triangular Prism Graph,

The graph family generated by the triangular prism graph and denoted by , is a recursive definition using the graphs and (triangle or ): a replica of is used in place of the middle triangle of to create the graph . The middle triangle in the graph is typically swapped out for to make , as shown in Figure 6. and are the total vertices and edges of , respectively. According to this architecture in the large limit, the average degree of is .

Figure 6.

(a) The graph (b) The graph .

Theorem 3.

For , the number of spanning trees in the graph family, generated by the triangular prism graph is given by the following:

where

Proof.

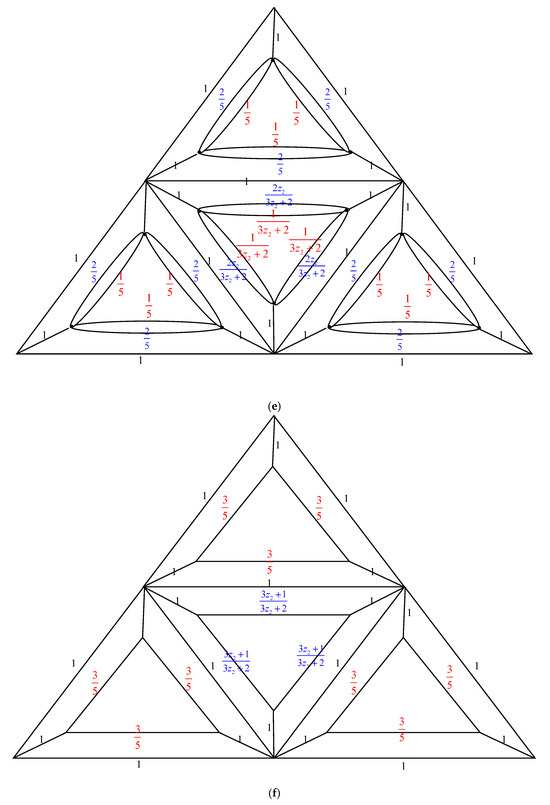

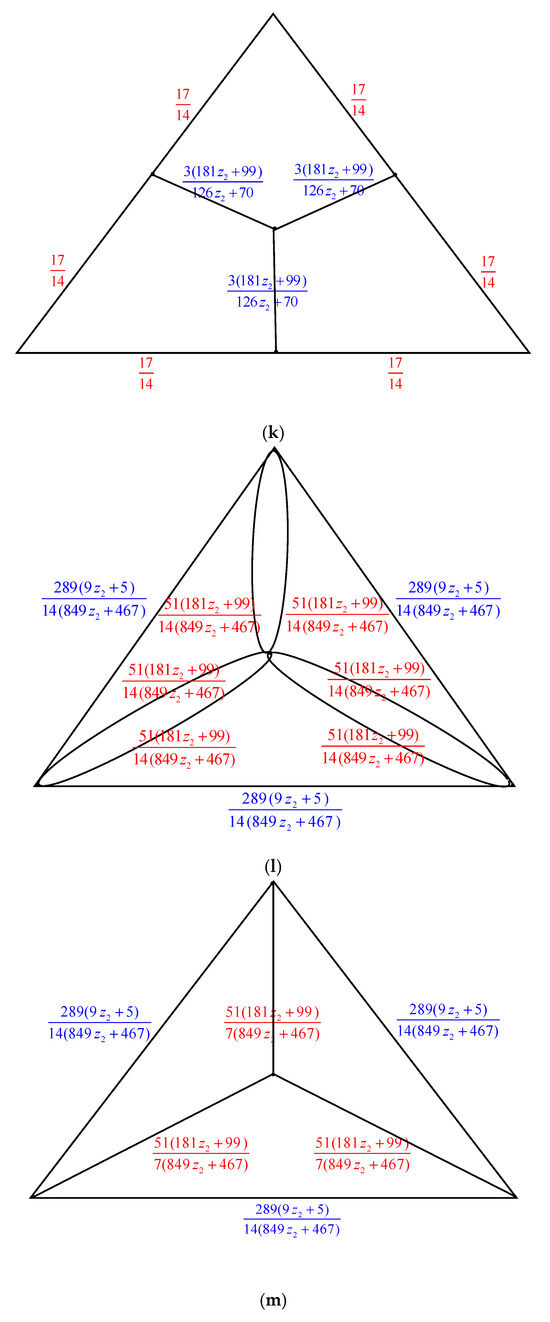

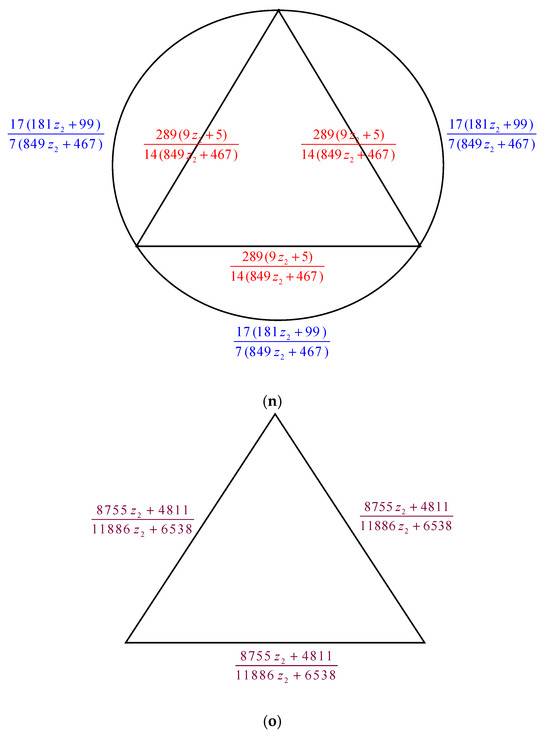

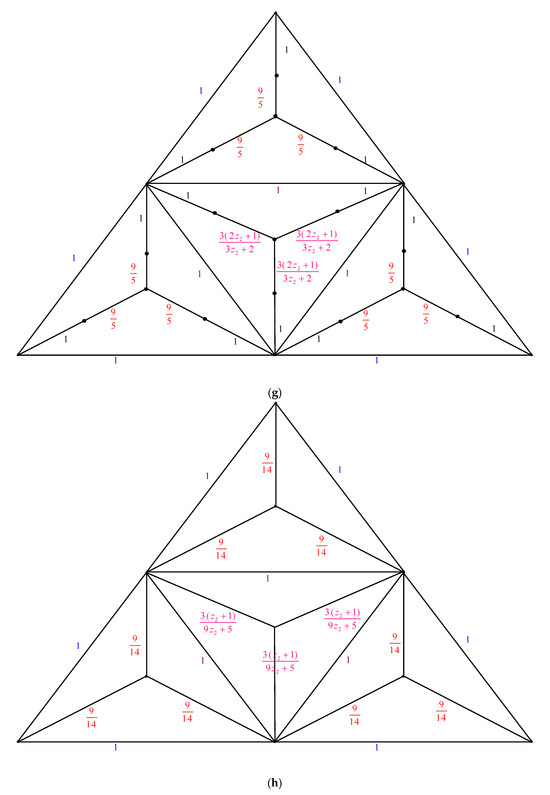

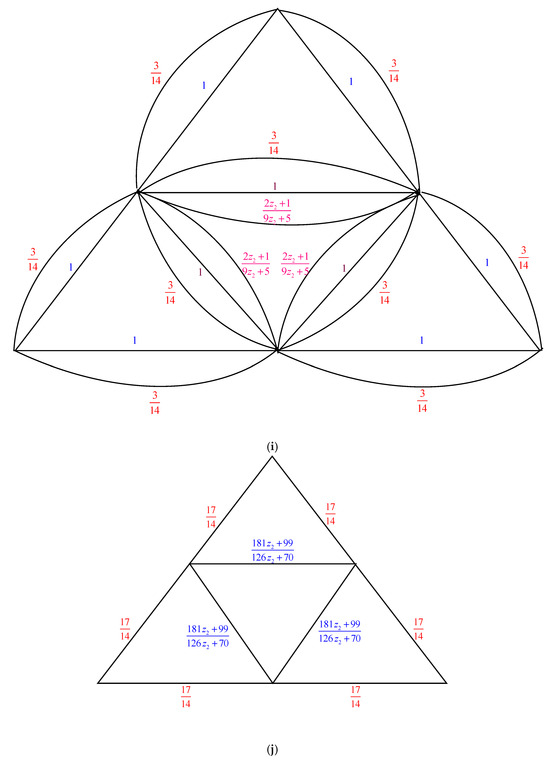

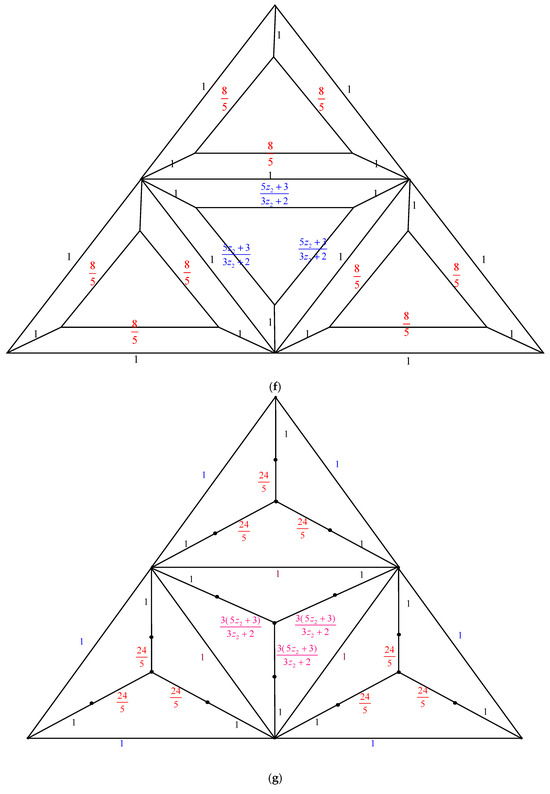

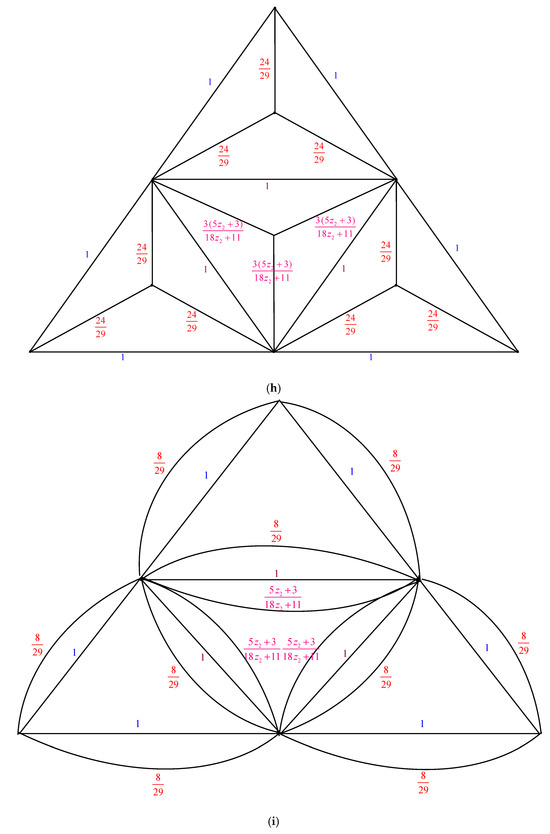

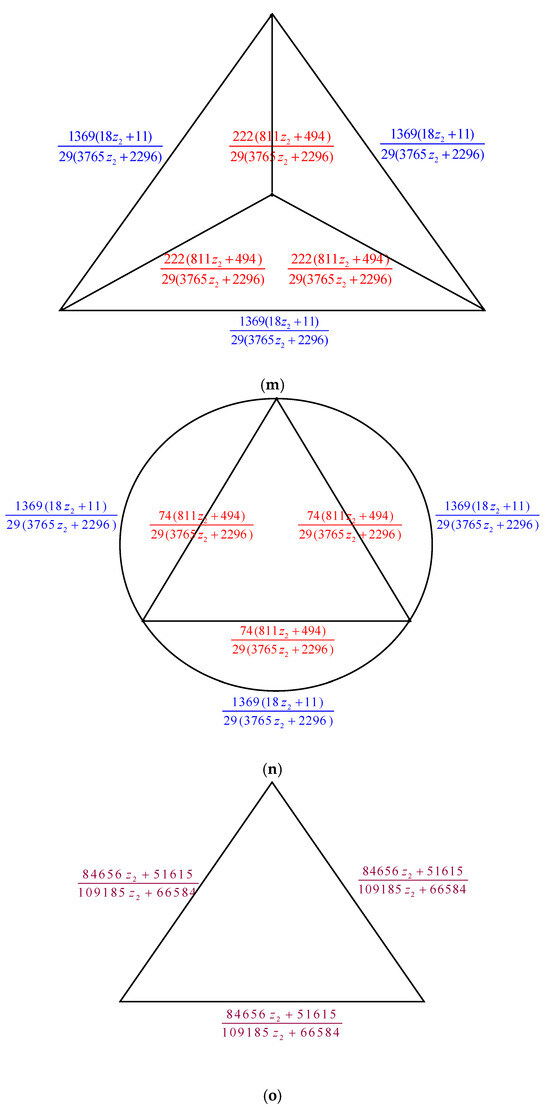

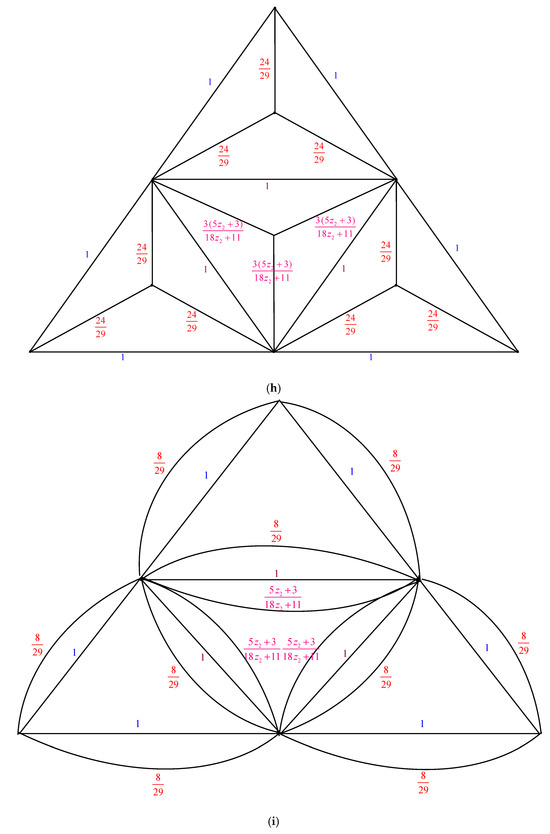

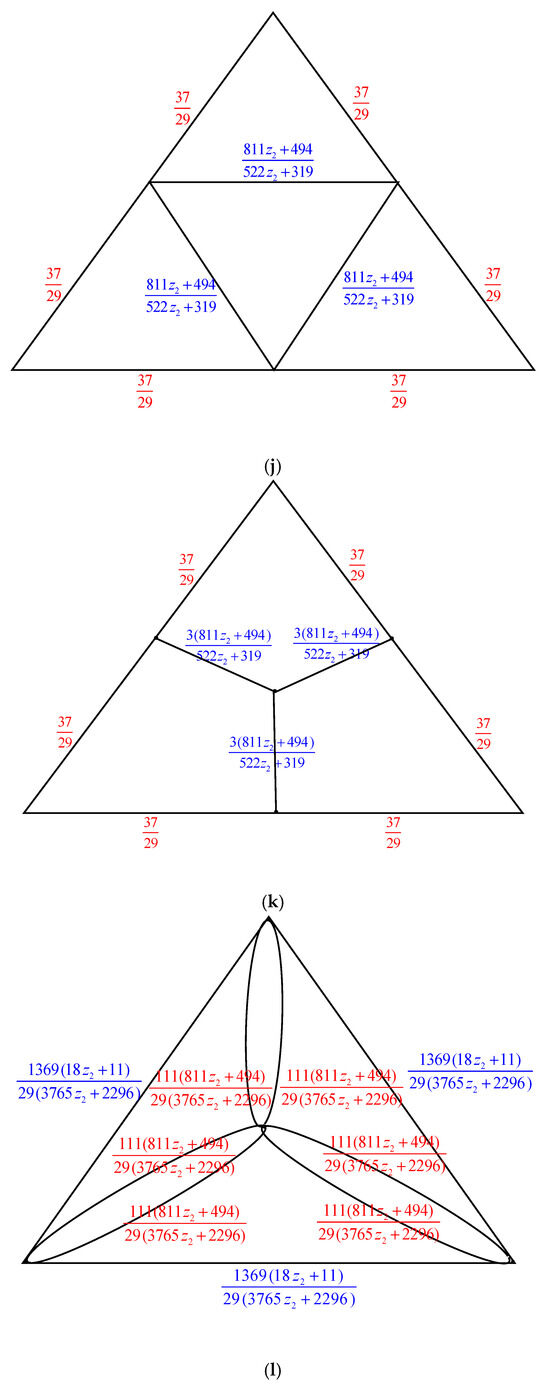

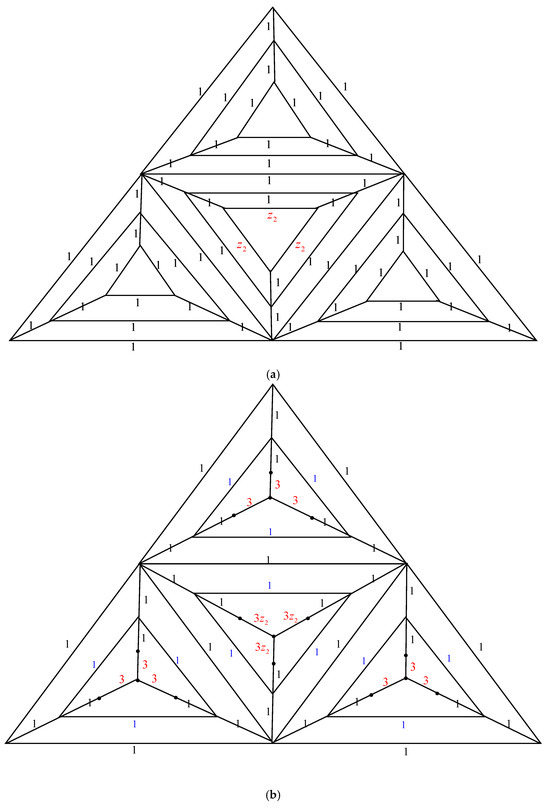

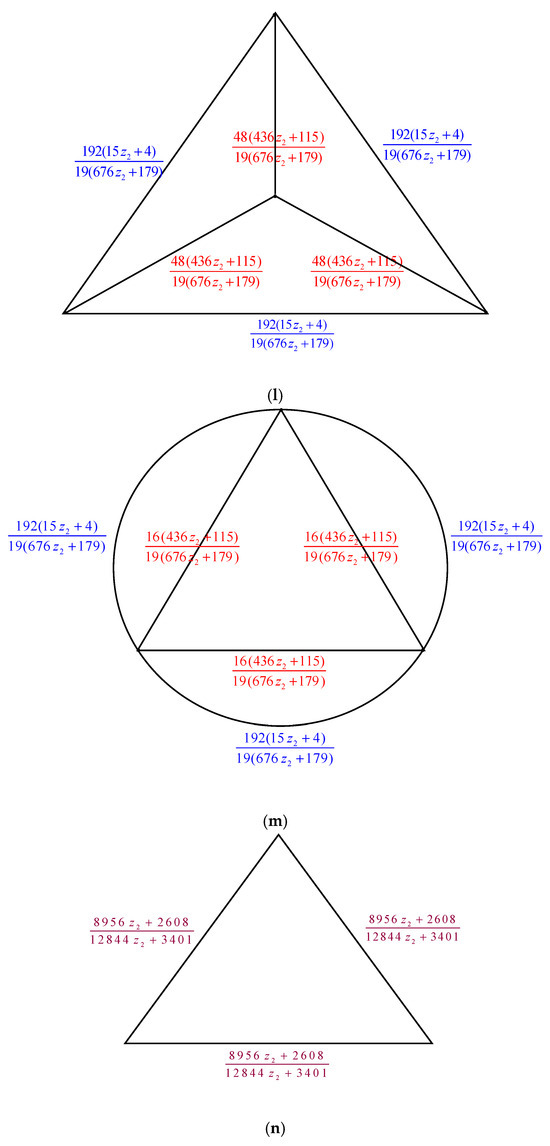

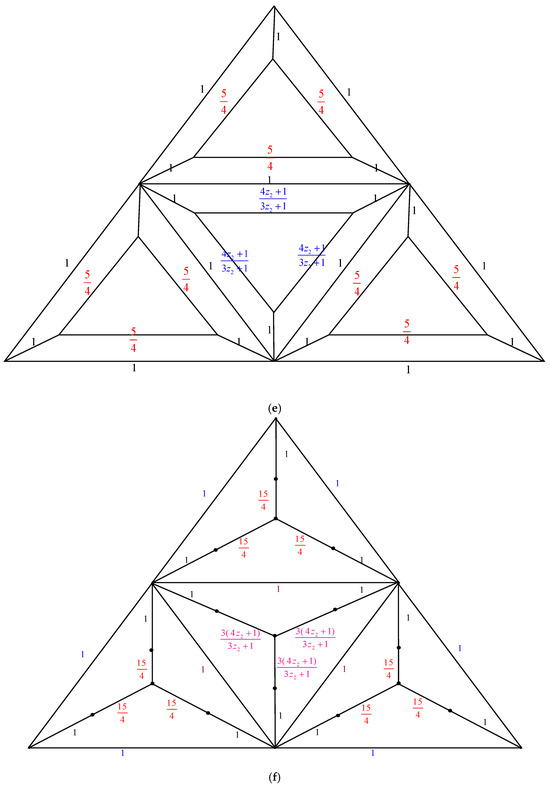

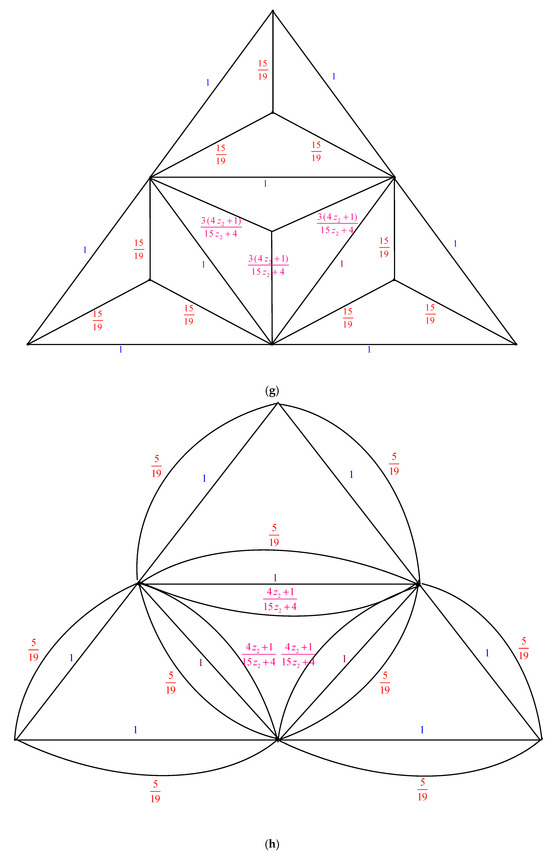

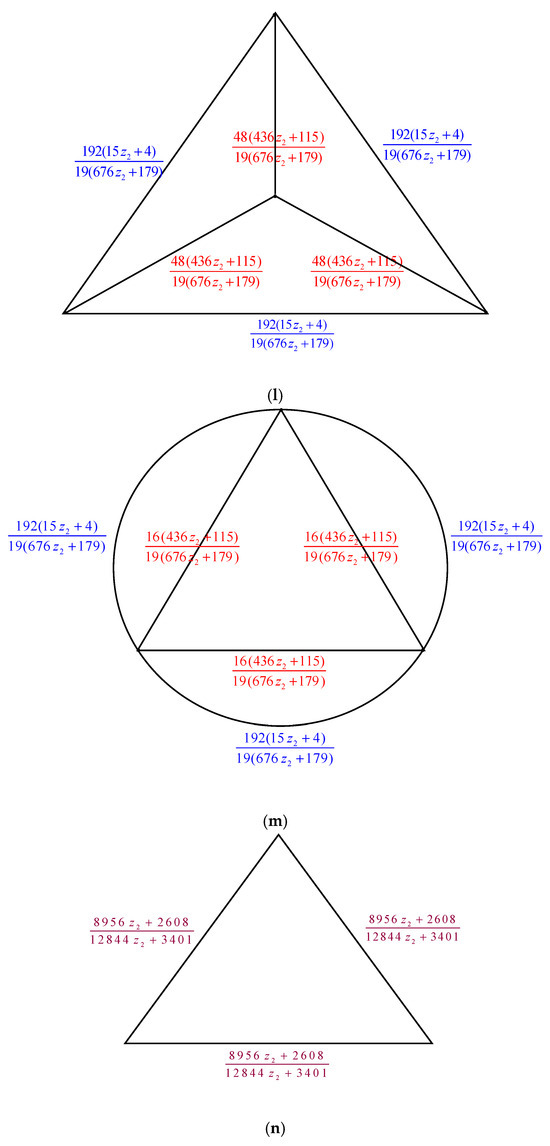

The electrically equivalent transformation is used to convert the graph to the graph . The process of transforming the graph into the graph is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The transformations from to (a) The graph . By applying the Δ-Y Transformation rule, we obtain (b) The graph . Using the serial edge rule, we obtain (c) The graph . When the Y-Δ Transformation rule is applied, we obtain (d) The graph . By utilizing the parallel edge rule, we arrive at . (e) The graph . Using the rule of Δ-Y Transformation, we obtain . (f) The graph . By applying the serial edge rule, we arrive at (g) The graph . Applying the rule of Y-Δ Transformation, we obtain . (h) The graph . The parallel edge rule yields the following results: . (i) The graph . By applying the Δ-Y Transformation rule, we obtain (j) The graph . The Y-Δ Transformation rule gives us (k) The graph . The parallel edge rule allows us to obtain (l) The graph . When the Y-Δ Transformation rule is applied, we obtain (m) The graph . By using the parallel edge rule, we obtain (n) The graph .

These thirteen transformations are combined to produce the following:

Thus, we have the following:

Furthermore,

where

Its characteristic equation is , with the following roots:

These two roots can be subtracted from both sides of to obtain the following:

Let . Then, .

Thus, using Equations (29) and (30), we obtain the following:

Therefore, .

From the expression , we have the following:

Then,

Thus,

If , we obtain the following:

Thus, we obtain the following:

Using expression and designating and as the coefficients of and , respectively, we obtain the following:

Thus, we obtain the following:

Using Equations (32) and (33) and the expression , we obtain the following:

The characteristic equation of Equation (35) is , with the following roots:

The general solutions of Equation (35) are .

Using the initial conditions and yields the following:

is devoid of any electrically equivalent transformation if . When Equation (36) is entered into Equation (34), we obtain the following:

When , , which is in accordance with Equation (37). Consequently, the number of spanning trees in the graph family generated by the triangular prism graph is determined by the following:

The required outcome is obtained by inserting Equation (31) into Equation (38). □

3. Numerical Results

The next three Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 display the values of the number of spanning trees in the three graph families , , and .

Table 1.

A portion of the spanning tree count for the graph family .

Table 2.

A portion of the spanning tree count for the graph family .

Table 3.

A portion of the spanning tree count for the graph family .

4. Spanning Tree Entropy

After obtaining precise formulas for the number of spanning trees in each of the three graph families,, , and we can calculate the spanning tree entropy , a finite number and an intriguing metric that defines the network topology. This is described in [12] as follows: Consider graph ,

From these results, we observe the following: graph families and , which have the same average degree , have the same entropy (1.040), while the graph family has more edges and average degrees than the graph families and ; its entropy is higher (1.27).

Additionally, the apollonian graph [13], which has an average degree of 5 (entropy 1.354), has a higher entropy than all graph families , , and . In addition, the entropy of the fractal scale free lattice [14], which has the entropy and average degree 4, is the same entropy of the graph families and while the entropies of the graph families and are smaller than the entropy of the two-dimensional Sierpinski gasket [15], which has an entropy of the same average degree 4. Finally, the entropy of graph families and is higher than the entropy of graph sequences and , constructed on the Johnson skeleton graph, which have the same mean score of 4 but an entropy value of 1.02 [11].

5. Conclusions

In this study, we calculated the number of spanning trees for three new and huge families of graphs that resulted from three new triangular prism graphs using the electrically equivalent transformation approach. The number of spanning trees for such families of graphs cannot be determined using Kirchhoff’s determinant method or the laborious computation of Laplace spectra. Thus, this is where this method’s strength is found. Additionally, we investigated the entropy of these graph families and how it related to the entropy of other graph families with average degrees that were identical or nearly equal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and S.N.D.; methodology, A.A. and S.N.D.; software, A.A. and S.N.D.; validation, A.A. and S.N.D.; formal analysis, A.A. and S.N.D.; investigation, A.A. and S.N.D.; resources, A.A. and S.N.D.; data curation, A.A. and S.N.D.; writing—original draft, A.A. and S.N.D.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and S.N.D.; visualization, A.A. and S.N.D.; supervision, A.A. and S.N.D.; project administration, A.A. and S.N.D.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University grant number RGP.2/229/46.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through Larg Groups (Project under grant number RGP.2/229/46).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Biggs, N.L. Algebraic Graph Theory, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, E.C.; Klein, D.J.; Mallion, R.B.; Pollak, P.; Sachs, H. A theorem for counting spanning trees in general chemical graphs and its application to toroidal fullerenes. Croat. Chem. Acta 2004, 77, 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Yong, X. Asymptotic enumeration theorems for the number of spanning trees and Eulerian trail in circulant digraphs & graphs. Sci. China Ser. A 1999, 43, 264–271. [Google Scholar]

- Applegate, D.L.; Bixby, R.E.; Chvátal, V.; Cook, W.J. The Traveling Salesman Problem: A Computational Study; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boesch, F.T.; Satyanarayana, A.; Suffel, C.L. A survey of some network reliability analysis and synthesis results. Networks 2009, 54, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, G. Über die Auflösung der Gleichungen auf welche man bei der Untersucher der linearen Verteilung galuanischer Strome gefhrt wird. Ann. Phys. Chem. 1847, 72, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelmans, A.K.; Chelnokov, V.M. A certain polynomial of a graph and graphs with an extremal number of trees. J. Comb. Theory B 1974, 16, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, S.N. Number of Spanning trees of cartesian and composition products of graphs and Chebyshev polynomials. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 71142–71157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, S.N. The Deletion—Contraction Method for Counting the Number of Spanning Trees of Graphs. Eur. J. Phys. Plus 2015, 130, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufl, E.; Wagner, S. On the number of spanning trees on various lattices. J. Phys. A 2010, 43, 415001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, A.; Daoud, S.N. Finding the number of spanning trees in specific graph sequences generated by a Johnson skeleton graph. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R. Asymptotic enumeration of spanning trees. Combin. Probab. Comput. 2005, 14, 491–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, B.; Comellas, F. The number of spanning trees in Apollonian networks. Discret. Appl. Math. 2014, 169, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Wu, B.; Zou, T. Spanning trees in a fractal scale—Free lattice. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 83, 016116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, W. Spanning trees on the Sierpinski gasket. J. Stat. Phys. 2007, 126, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).