Research on the Behavioral Strategies of Manufacturing Enterprises for High-Quality Development: A Perspective on Endogenous and Exogenous Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Description and Model Assumptions

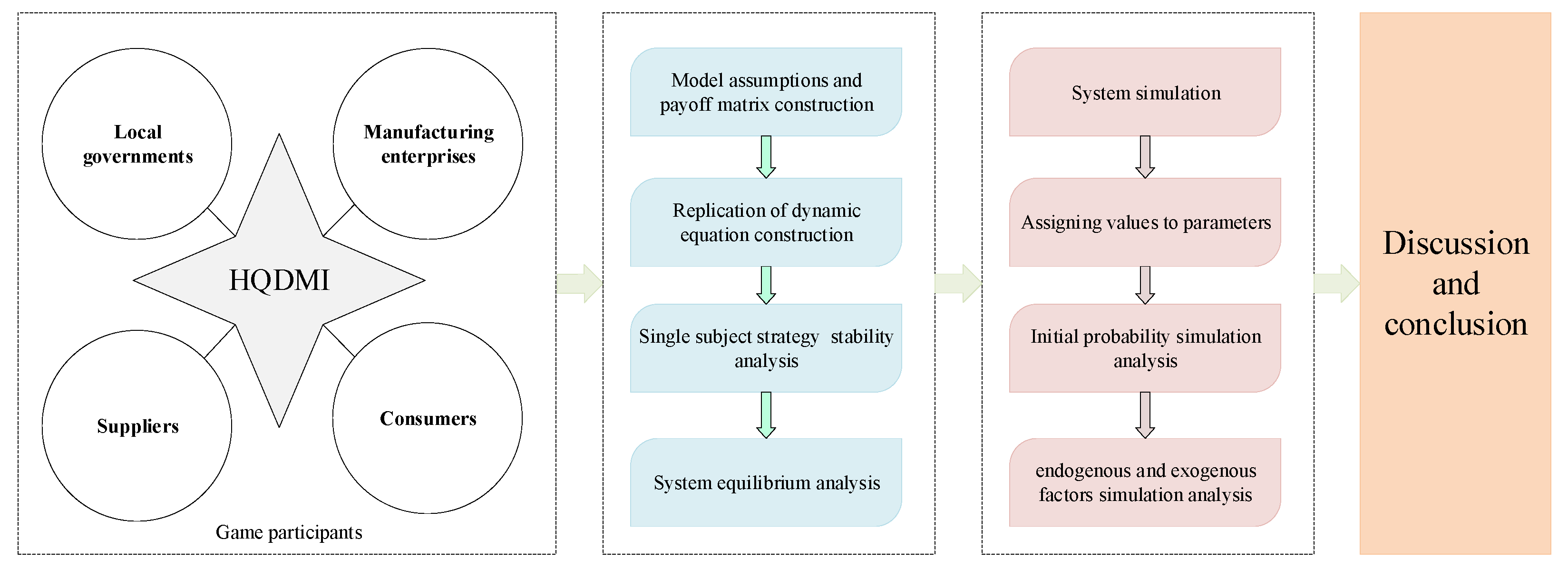

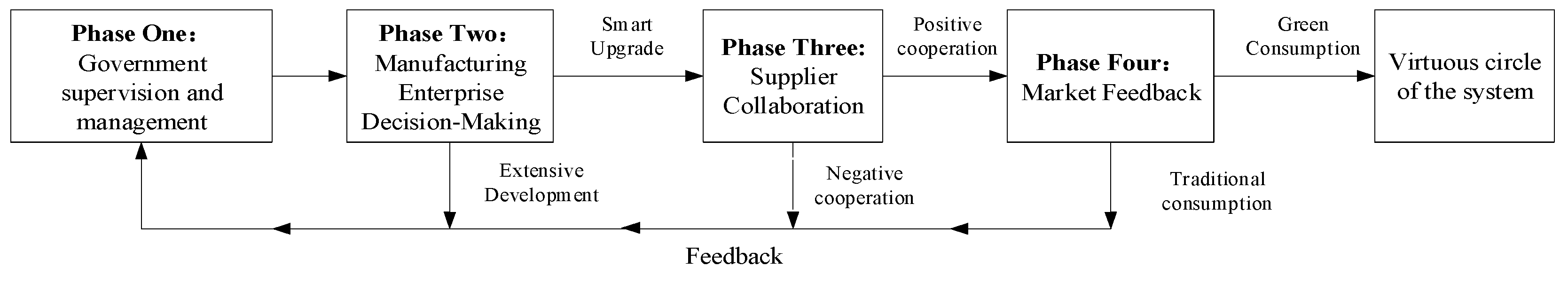

2.1. Research Methods and Framework

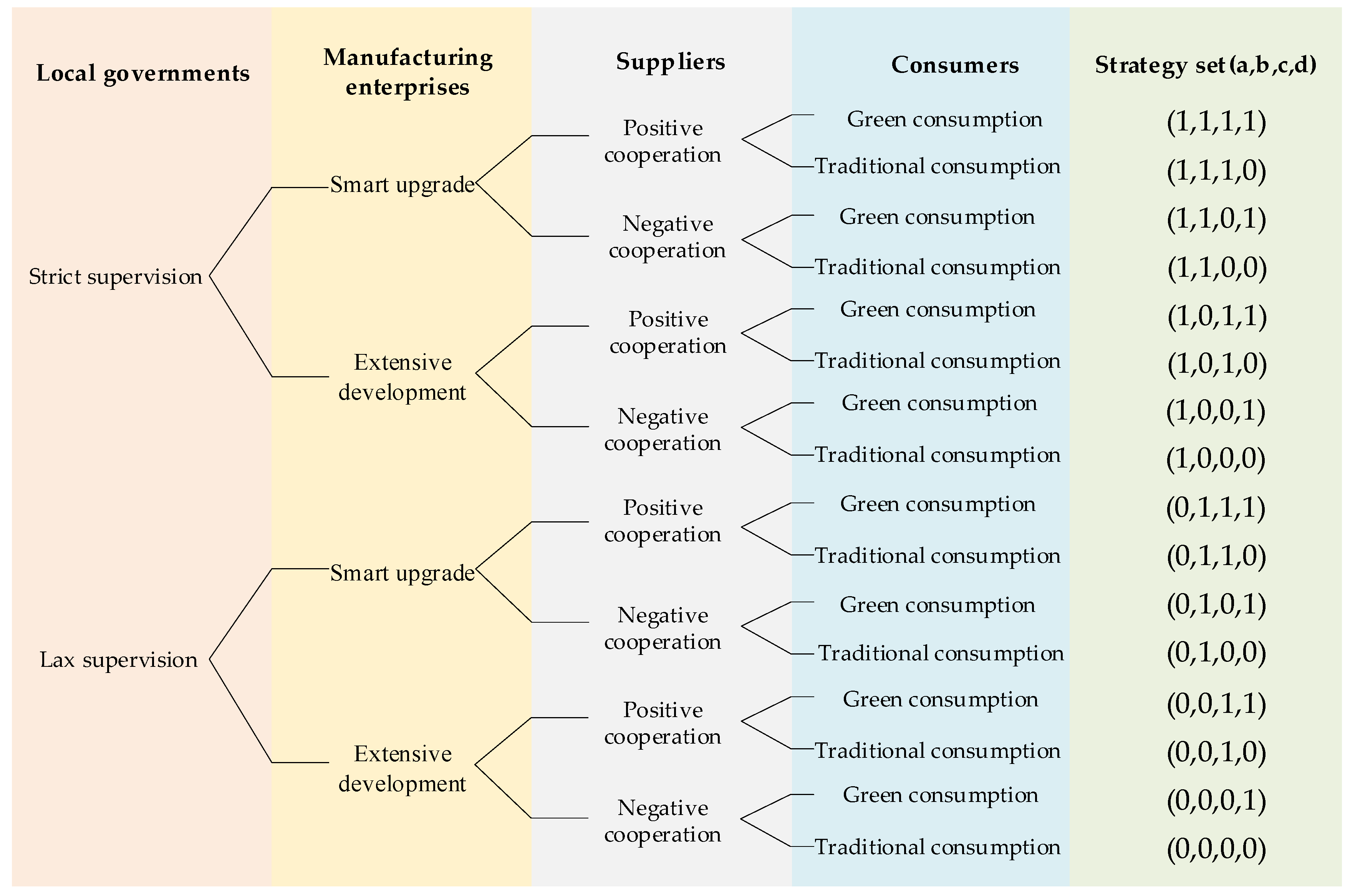

2.2. Problem Description

2.3. Model Assumptions

2.4. Model Construction

2.5. Solving the Stable Strategy Equilibrium Solution

2.5.1. Constructing the Payoff Expectation Functions

2.5.2. Model Analysis

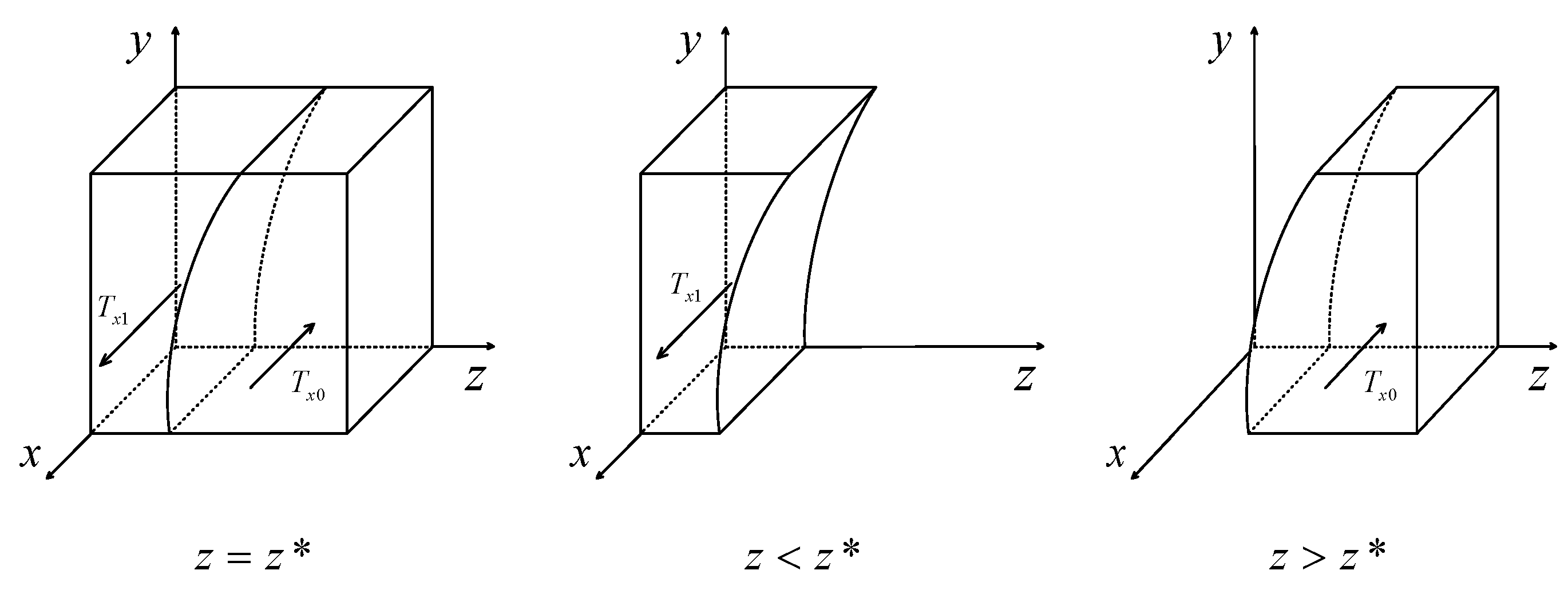

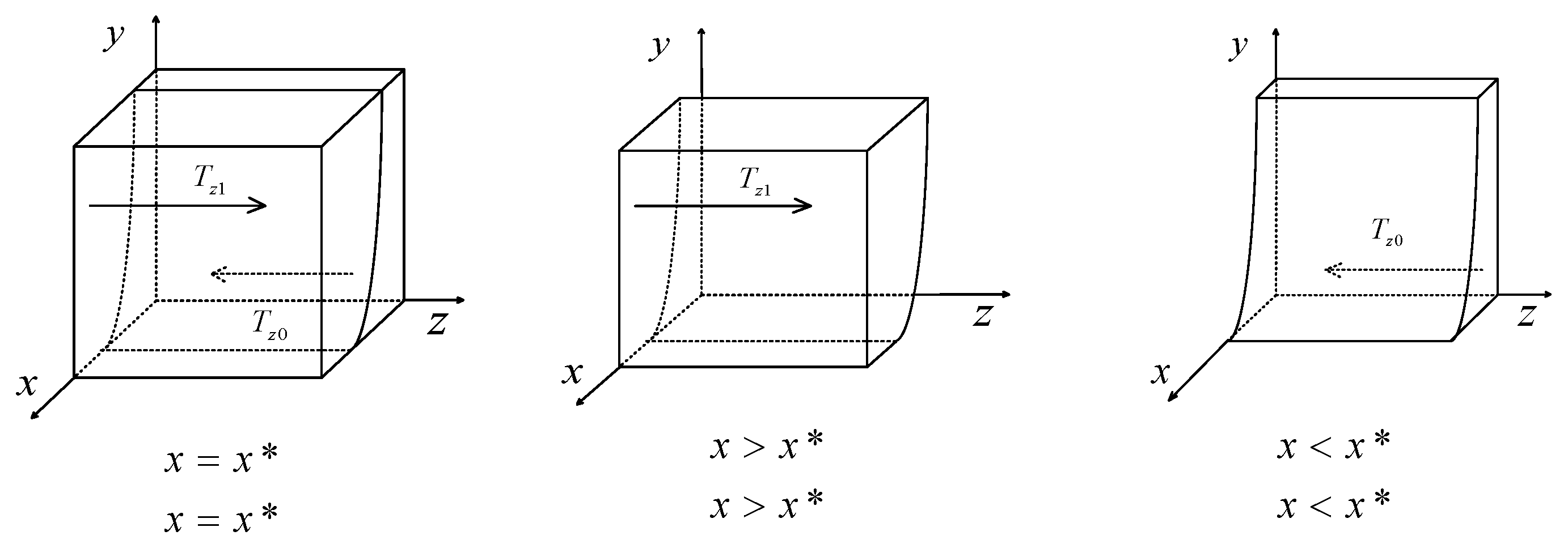

Analysis of Evolutionarily Stable Strategy of Local Governments

Analysis of Evolutionarily Stable Strategy of Manufacturing Enterprises

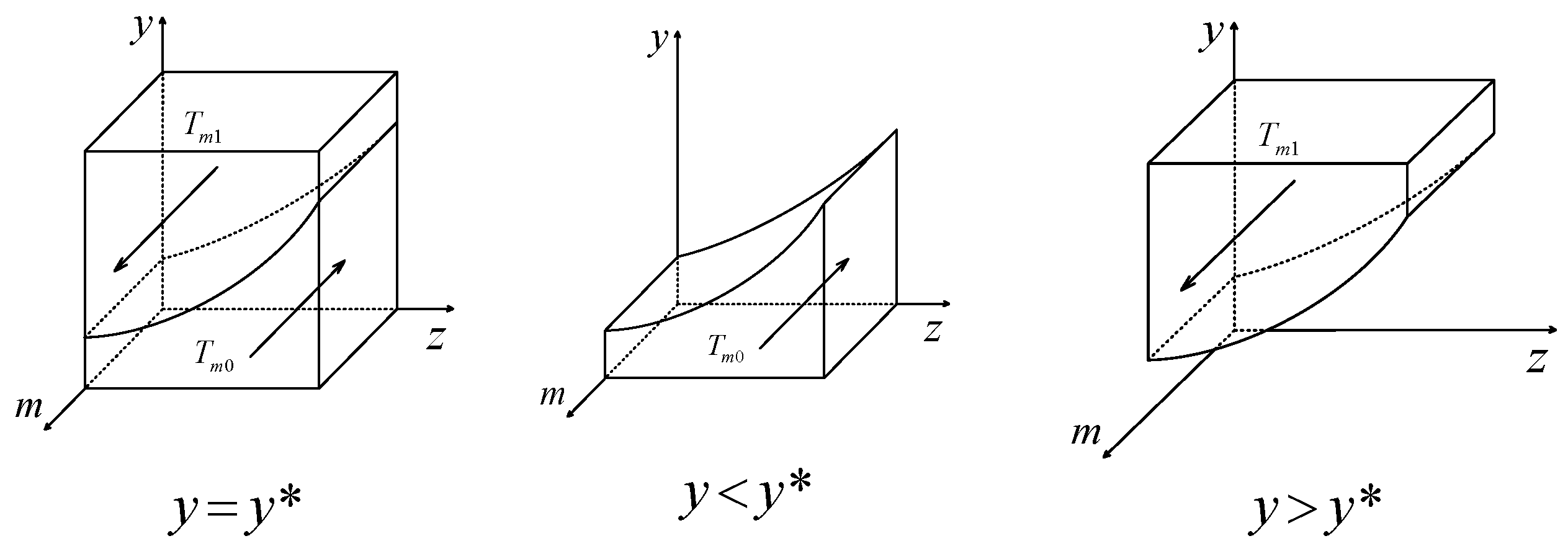

Analysis of Evolutionarily Stable Strategy of Suppliers

Analysis of Evolutionarily Stable Strategy of Consumers

2.5.3. System Equilibrium Analysis

3. System Simulation Analysis

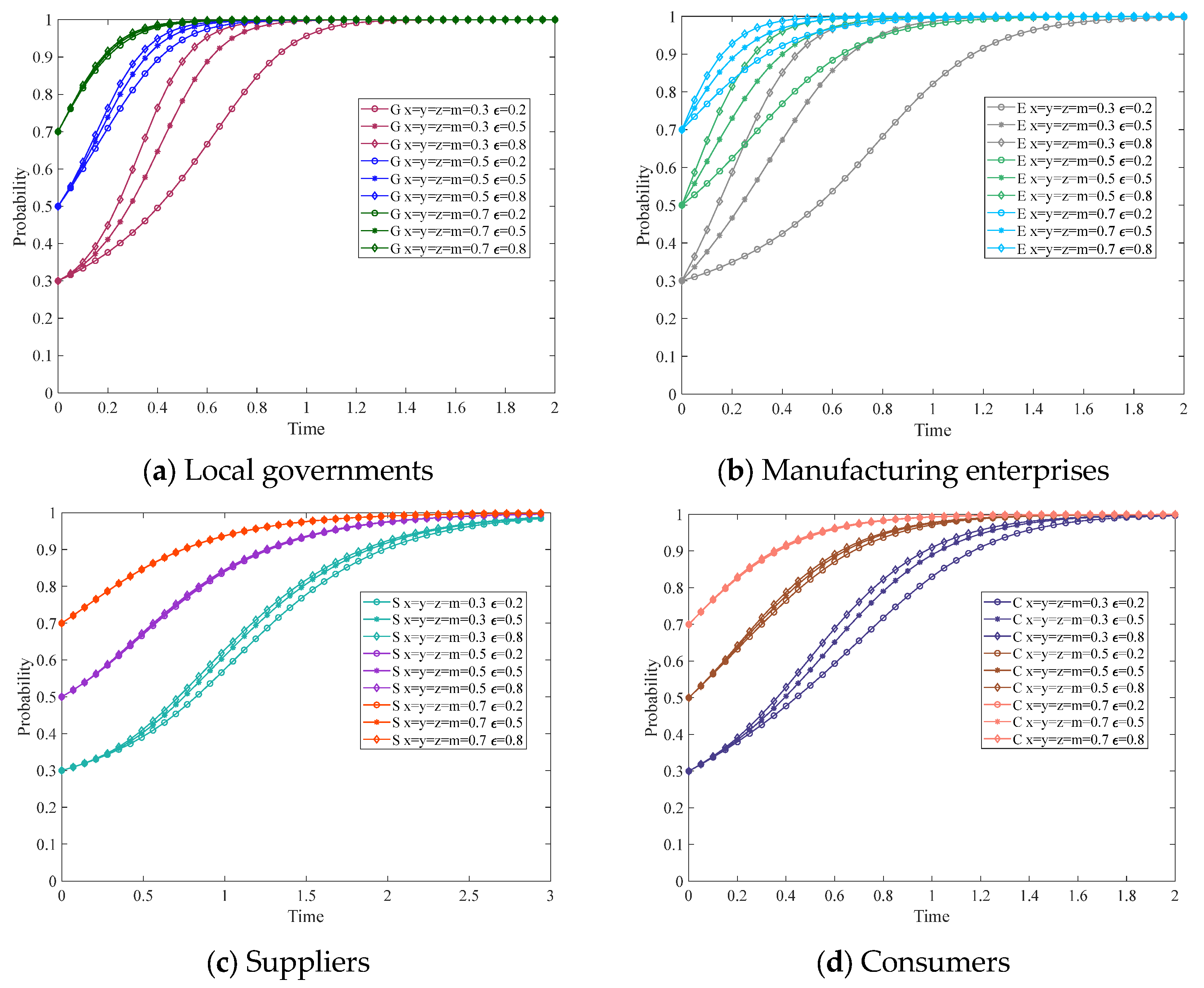

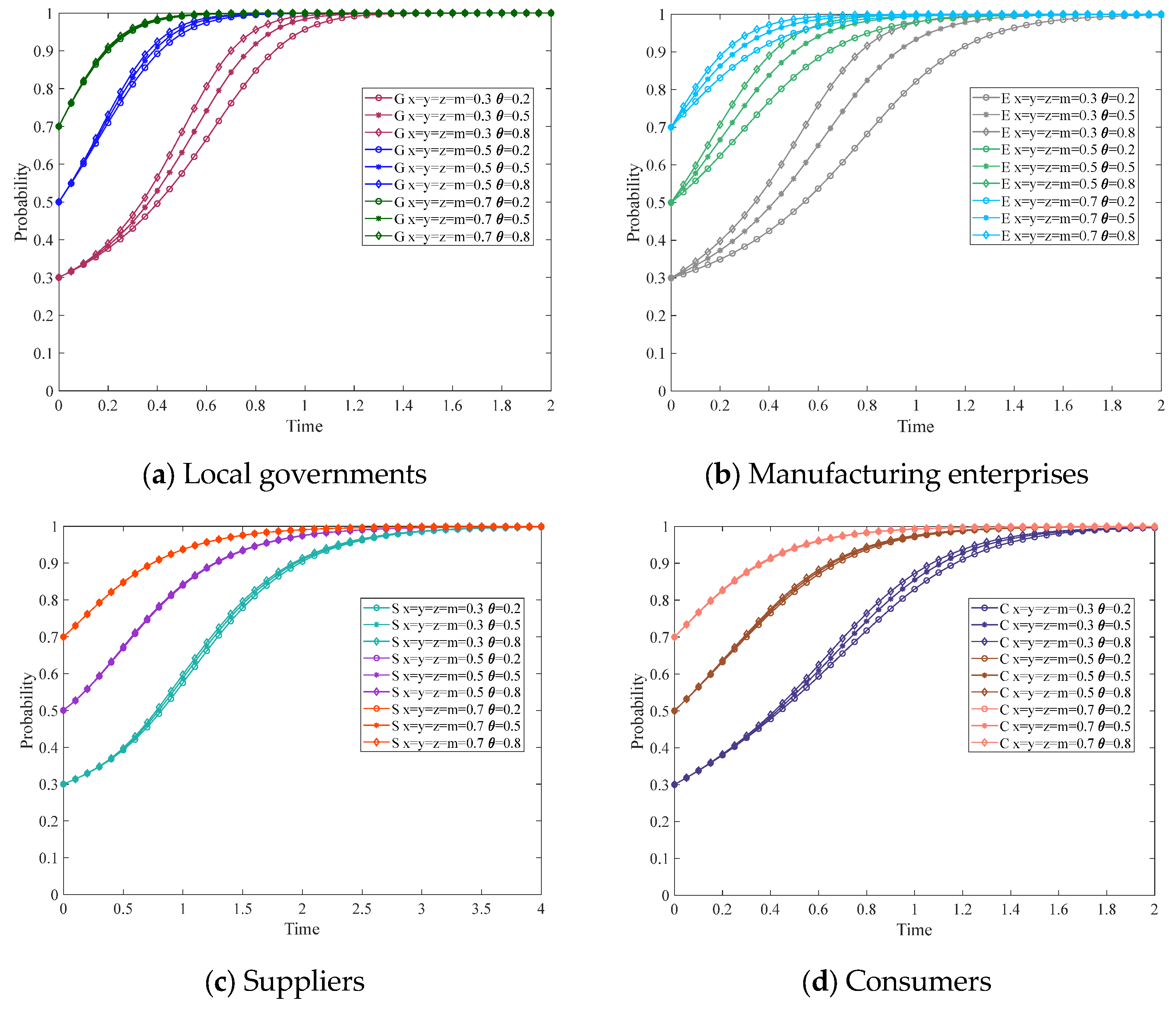

3.1. The Impact of the Innovative Capability Factor on the System

3.2. The Impact of the Organization Building Factor on the System

3.3. The Impact of the Industrial Resources Factor on the System

3.4. The Impact of the Policy Environment Factor on the System

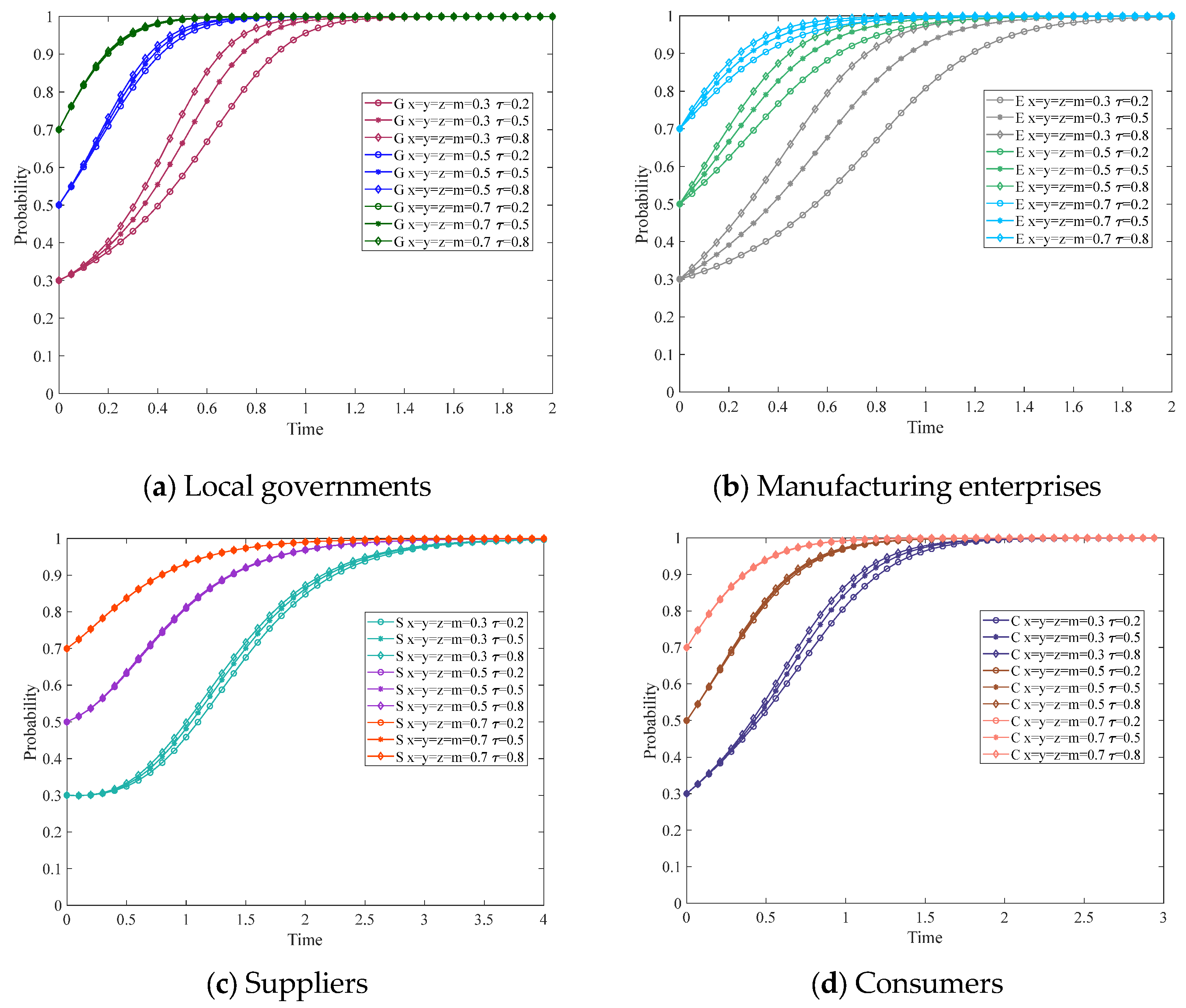

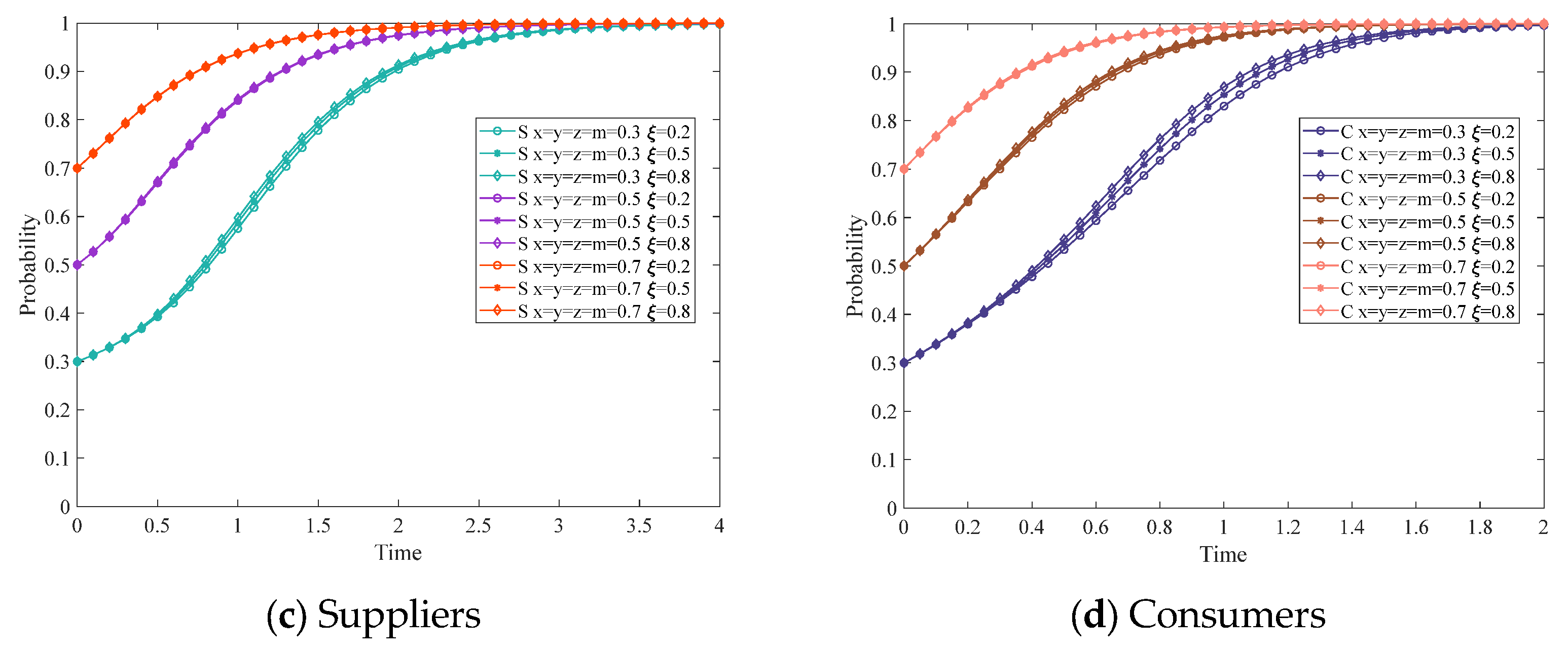

3.5. The Impact of the Industrial Cooperation Factor on the System

3.6. The Impact of the Market Demand Factor on the System

4. Discussion

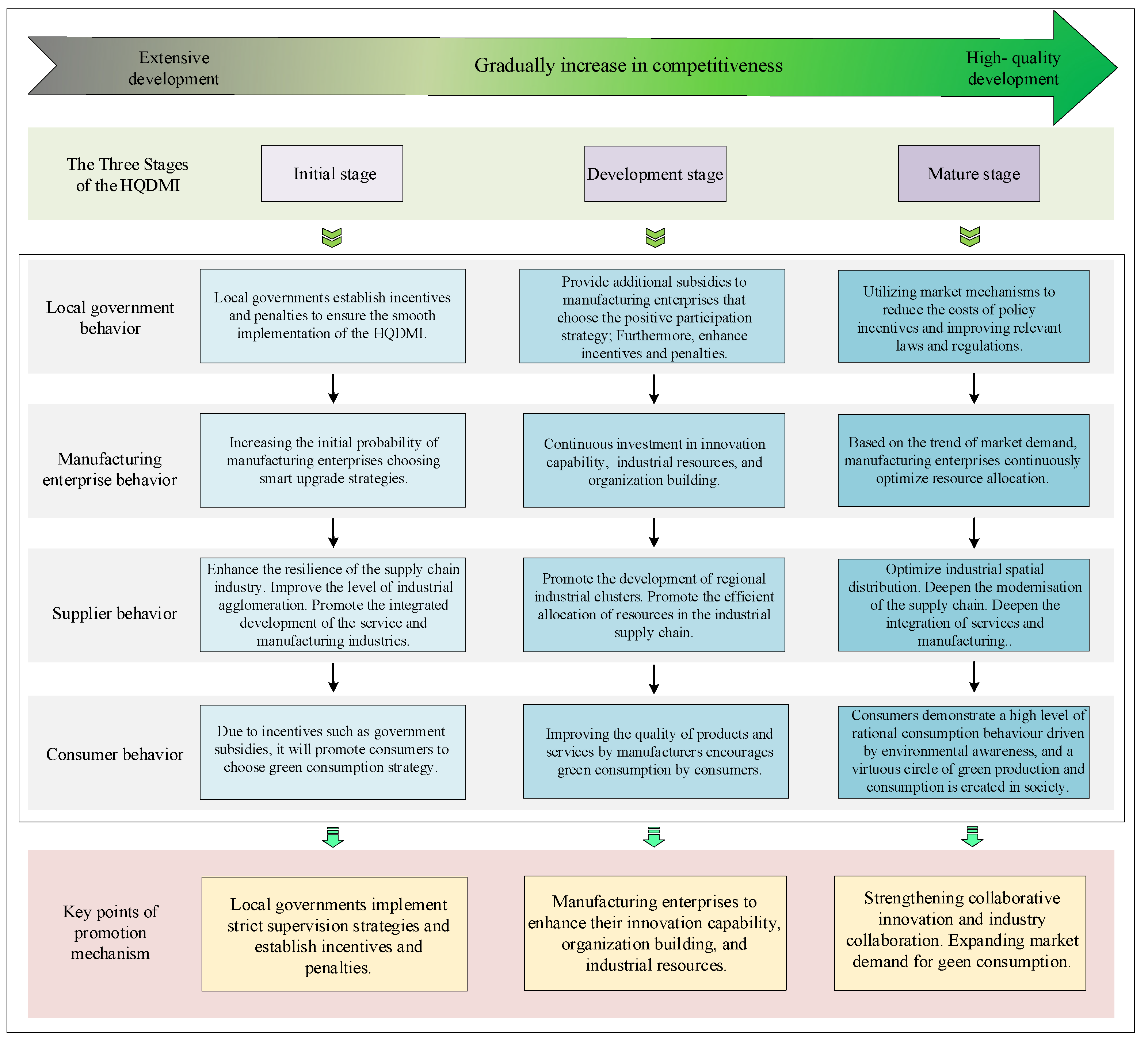

4.1. The Promotion Mechanism of the HQDMI

4.2. Managerial Insights

5. Conclusions and Limitations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Panda, S.K.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, R. Dynamic resource matching in manufacturing using deep reinforcement learning. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 318, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, J. Can digital transformation enable the energy enterprises to achieve high-quality development?: An empirical analysis from China. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 1182–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Khanna, A. A holistic approach to sustainable manufacturing: Rework, green technology, and carbon policies. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 244, 122943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Z.; Jiang, F.; Yan, L.; Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Esposito, L. Nexus between enterprise innovation and viability: Strategic differentiation of China manufacturing sector unveils the truth. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 7757–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J. Green credit, carbon emission and high quality development of green economy in China. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 12215–12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, W.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, T. Spatiotemporal and driving forces of Ecological Carrying Capacity for high-quality development of 286 cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Li, C.; Shi, J.; Wang, N. The impact of high-quality development on ecological footprint: An empirical research based on STIRPAT model. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Z. Synergistic industrial agglomeration, new quality productive forces and high-quality development of the manufacturing industry. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 94, 103373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y. Does environmental regulation promote the high-quality development of manufacturing? A quasi-natural experiment based on China’s carbon emission trading pilot scheme. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 81, 101216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Roman Pais Seles, B.M. Sustainable development in Asian manufacturing SMEs: Progress and directions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 225, 107567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Mani, K.T.N. Supply chain social sustainability in small and medium manufacturing enterprises and firms’ performance: Empirical evidence from an emerging Asian economy. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafetzopoulos, D.; Psomas, E. The impact of innovation capability on the performance of manufacturing companies. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2015, 26, 104–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ren, B. Study on the high-quality development and competitiveness of manufacturing industry of the Yellow River Basin. Econ. Probl. 2020, 8, 1–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Wang, X. Spatial transfer trend and its effect factors of manufacturing industry in China: 2007~2017. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2020, 37, 26–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ma, H.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, J.; Divakaran, P.K.P. Manufacturing structure, transformation path, and performance evolution: An industrial network perspective. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, V. Service strategies within the manufacturing sector: Benefits, costs and partnership. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2001, 12, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Hu, Q. The theoretical framework of the construction of the strategic competitive advantage of the service-oriented manufacturing industry: Based on multi-case analysis of manufacturing industry. China Bus. Mark. 2020, 34, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J. Deepening understanding of accelerating the formation of a new development pattern. Econ. Perspect. 2020, 10, 3–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, D. Thinking on development of emerging industries of strategic importance in new stage. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2021, 36, 328–335. [Google Scholar]

- Dechao, H. The Growth of Service Sectors, Institutional Environment and Quality Development in China’s Manufacturing. Systems 2023, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C. Regional business environment and high-quality development of private enterprises: Empirical evidence from China. Res. Econ. Manag. 2021, 42, 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Yao, P. Industrial policy and high-quality development of manufacturing. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2020, 38, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D. Theoretical connotation, scientific basis and path selection of green and high quality development path in China. Chongqing Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Yang, Y. An analysis on the connotation and development of the modernization of Chinese industrial and supply chains. J. Renmin Univ. China 2022, 36, 120–134. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Industrial agglomeration and economic growth in the Yellow River Basin: Pattern, characteristics and path. Econ. Probl. 2022, 3, 20–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, K. Artificial intelligence, structural transformation and labor share. J. Manag. World 2019, 35, 60–77+202–203. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Wu, J.; Li, Q. The power and path of service oriented equipment manufacturing Industry in the digital economy era. Jianghai Acad. J. 2022, 4, 92–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Subin, I.; John, P.; Workman, J. Market orientation, creativity, and new product performance in high-technology firms. J. Mark. Res. 2004, 68, 114–132. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, D.; Vasconcelos, S. Essays on duopoly competition with asymmetric firms: Is profit maximization always an evolutionary stable strategy? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 225, 107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, C. How can stakeholders collaborate to promote the interconnection of charging infrastructure? A tripartite evolutionary game analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Hu, Z.-H. Using evolutionary game theory to study governments and manufacturers’ behavioral strategies under various carbon taxes and subsidies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhao, X. Firms’ technological strategies in an innovation ecosystem: A dynamic interaction between leading firms and following firms based on evolutionary game theory and multi-agent simulation. J. Manag. Sci. China 2022, 25, 13–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, W.; Yin, X. Understanding the impact on energy transition of consumer behavior and enterprise decisions through evolutionary game analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2021, 28, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Su, Y. Behavioural strategies of manufacturing firms for high-quality development from the perspective of government participation: A three-part evolutionary game analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Bai, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, J. Incentives for Green and Low-Carbon Technological Innovation of Enterprises Under Environmental Regulation: From the Perspective of Evolutionary Game. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 9, 793667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Bao, H. FinTech regulation: Evolutionary game model, numerical simulation, and recommendations. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 211, 118327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Sun, S. Low-carbon transition pathways in the context of carbon-neutral: A quadrilateral evolutionary game analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 116105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iorio, V.; Testa, F.; Korschun, D.; Iraldo, F.; Iovino, R. Curious about the circular economy? Internal and external influences on information search about the product lifecycle. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2193–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Ma, X.; Li, G. Developing green purchasing relationships for the manufacturing industry: An evolutionary game theory perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 166, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Miao, X.; Qiu, Y. A research on the competition and countermeasures of the integrated circuit industry development in China. Sci. Res. Manag. 2021, 42, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Yang, Y. Research on Air Pollution Control in China: From the Perspective of Quadrilateral Evolutionary Games. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, C.; Schossau, J.; Hintze, A. The reasonable effectiveness of agent-based simulations in evolutionary game theory Reply to comments on “Evolutionary game theory using agent-based methods”. Phys. Life Rev. 2016, 19, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Babu, S.; Mohan, U. An integrated approach to evaluating sustainability in supply chains using evolutionary game theory. Comput. Oper. Res. 2018, 89, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivan, V.; Galanthay, T.E.; Cressman, R. Beyond replicator dynamics: From frequency to density dependent models of evolutionary games. J. Theor. Biol. 2018, 455, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Pan, M.; Peng, D. Replicator dynamics and evolutionary game of social tolerance: The role of neutral agents. Econ. Lett. 2017, 159, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, N.; Chen, X. Replicator dynamics for public goods game with resource allocation in large populations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 328, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Jonker, L. Evolutionary stable strategies and game dynamics. Math. Biosci. 1978, 40, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D. On economic applications of evolutionary game theory. J. Evol. Econ. 1998, 8, 15–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Quadripartite evolutionary game of public participation in interactive transboundary pollution control compensation. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 32, 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y. Multi-agent evolutionary game in the recycling utilization of construction waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 139826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, C.; Mao, J.; Yang, Q. What affects the implementation of the renewable portfolio standard? An analysis of the four-party evolutionary game. Renew. Energy 2023, 204, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Jia, M.; Wang, L.; Sharma, G.D.; Zhao, X.; Ma, X. Modelling and simulation of a four-group evolutionary game model for green innovation stakeholders: Contextual evidence in lens of sustainable development. Renew. Energy 2022, 197, 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, J. Influence of environmental regulations on industrial transformation of resource–based cities in the Yellow River Basin under resource endowment. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2020, 35, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Huang, J.; Yuan, K. The embedded location of value chain and the domestic value added ratio of exports. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2019, 36, 41–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Song, S.; Jiao, J.; Yang, R. The impacts of government R&D subsidies on green innovation: Evidence from Chinese energy-intensive firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 819–829. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Shi, D.; Deng, Z. A framework of China’s high-quality economic development. Res. Econ. Manag. 2019, 40, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

| Subjects | Parameters | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Local governments | The benefits obtained by the government when manufacturing enterprises choose “smart upgrade” strategy | |

| The initial benefits of the government when manufacturing enterprises choose “extensive development” strategy | ||

| Cost by local governments in enhancing the policy environment | ||

| Subsidies offered by local governments to manufacturing enterprises who choose “smart upgrade” strategy | ||

| Rewards offered by local governments to suppliers who choose positive cooperation strategy | ||

| Subsidies offered by local governments to consumer s who choose green consumption strategy | ||

| The coefficient of increased benefits for the government due to the choice of “smart upgrade” strategy by manufacturing enterprises | ||

| Manufacturing enterprises | Initial benefit of manufacturing enterprises | |

| Benefits to manufacturing enterprises for smart upgrade | ||

| The investment by manufacturing enterprises on innovative capability | ||

| The investment by manufacturing enterprises on organization building | ||

| The investment by manufacturing enterprises on industrial resources | ||

| Benefits gained by manufacturing enterprises adopting the smart upgrade strategy when local governments adopt the strict supervision strategy | ||

| Benefits gained by manufacturing enterprises adopting the smart upgrade strategy when suppliers adopt the positive cooperation strategy | ||

| Benefits gained by manufacturing enterprises adopting the smart upgrade strategy when consumers adopt the green consumption strategy | ||

| Contractual losses incurred by manufacturing enterprises that adopt the extensive development strategy when suppliers adopt the positive cooperation strategy | ||

| Suppliers | Initial benefit of suppliers | |

| Benefits to suppliers for positive cooperation | ||

| Costs to suppliers for positive cooperation | ||

| Added benefits incurred by suppliers that adopt the negative cooperation strategy when consumers adopt the green consumption strategy | ||

| Loss costs incurred by suppliers that adopt the positive cooperation strategy when consumers adopt the traditional consumption strategy | ||

| Contractual losses incurred by suppliers that adopt the negative cooperation strategy when manufacturing enterprises adopt the smart upgrade strategy | ||

| Consumers | Initial benefit of consumers | |

| The direct benefit when consumers adopt the “green consumption” strategy | ||

| The cost when consumers adopt the “green consumption” strategy | ||

| The benefits of adopting a “green consumption” strategy for consumers when suppliers choose a “positive cooperation” strategy | ||

| The benefits of adopting a “green consumption” strategy for consumers when manufacturing enterprises choose the “smart upgrade” strategy | ||

| Variables | Descriptions | |

| Factor of innovative capability | ||

| Factor of organization building | ||

| Factor of industrial resources | ||

| Factor of policy environment | ||

| Factor of industrial cooperation | ||

| Factor of market demand | ||

| The probability of local governments adopting the “strict supervision” strategy | ||

| The probability of manufacturing enterprises adopting the “smart upgrade” strategy | ||

| The probability of suppliers adopting the “positive cooperation” strategy | ||

| The probability of consumers adopting the “green consumption” strategy |

| Local Governments | Manufacturing Enterprises | Suppliers | Consumers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Consumption | ||||

| Strict supervision | Smart upgrade | Positive cooperation | ||

| Negative cooperation | ||||

| Extensive development | Positive cooperation | |||

| Negative cooperation | ||||

| Lax supervision | Smart upgrade | Positive cooperation | ||

| Negative cooperation | ||||

| Extensive development | Positive cooperation | |||

| Negative cooperation | ||||

| Equilibrium Point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium Point | Stability and Condition | Ideality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| ESS (Condition 1) | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| ESS (Condition 2) | Undesirable | |||||

| Unstable point | Undesirable | |||||

| ESS (Condition 3) | Undesirable | |||||

| ESS (Condition 4) | Desirable |

| 15 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 20 | 2 | 13 |

| 7 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 30 | 17.5 | 12 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, M. Research on the Behavioral Strategies of Manufacturing Enterprises for High-Quality Development: A Perspective on Endogenous and Exogenous Factors. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3165. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13193165

Su Y, Shi J, Zhang M. Research on the Behavioral Strategies of Manufacturing Enterprises for High-Quality Development: A Perspective on Endogenous and Exogenous Factors. Mathematics. 2025; 13(19):3165. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13193165

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Yongqiang, Jinfa Shi, and Manman Zhang. 2025. "Research on the Behavioral Strategies of Manufacturing Enterprises for High-Quality Development: A Perspective on Endogenous and Exogenous Factors" Mathematics 13, no. 19: 3165. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13193165

APA StyleSu, Y., Shi, J., & Zhang, M. (2025). Research on the Behavioral Strategies of Manufacturing Enterprises for High-Quality Development: A Perspective on Endogenous and Exogenous Factors. Mathematics, 13(19), 3165. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13193165