1. Introduction

The motivation behind this paper is the computation of Koszul–Vinberg cohomology, which is closely related to information geometry through appropriate spectral sequences, resulting in a powerful machinery successfully applied in various problems arising in differential topologies and differential geometries. A Koszul connection [

1] can be viewed informally as means for taking the derivative of a section

s of a vector bundle

, with

M being a smooth manifold, along a vector field

. The resulting section is denoted by

, with ∇ as the connection. It defines an

-bilinear product on sections by

whose commutator is the Lie bracket if ∇ is torsion-free. The associator of the product

can be easily computed as

, meaning that

. When the connection ∇ is flat,

, turning the real vector space of sections into a Koszul–Vinberg algebra, also called a pre-Lie algebra [

2]. This fact is used in

Section 3 to introduce a cohomology from which spectral sequences of interest arise.

The second key ingredient is an important concept coming from the general theory of Koszul connections is the gauge equation. If ∇ is a Koszul connection on the bundle E and is a bundle isomorphism, then is a Koszul connection. This defines an action of the gauge group on Koszul connections; when two connections are in the same conjugacy class, there exists in the gauge group such that , or equivalently, Relaxing the invertibility assumption on gives rise to the so-called gauge equation: two connections on a vector bundle are said to satisfy a gauge equation if there exists a bundle morphism such that Without additional assumptions on , any global section of satisfies a gauge equation.

Thus, is thus necessary to place some constraints on the couple in order to obtain useful results. In this paper, we focus on dual connections as provided by statistical manifolds.

The concept of a statistical manifold comes from the field of information geometry. It is defined as a quadruple

, where

is a smooth Riemannian manifold and

are torsion-free Koszul connections on

that satisfy the metric relation [

3]

One connection ∇ or entirely defines the other; however, the extra assumption that these are both torsion-free is not automatically satisfied. In the present work, we focus on the case where the gauge equation is satisfied by two connections coming from a statistical manifold. In particular, two remarkable webs are defined that give rise to spectral sequences of interest. To the best knowledge of the authors, the results presented here are new.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, basic facts about the gauge equation in the general settings are briefly recapped, then some equivalent formulations are provided and important parallel tensors are defined; these represent original contributions of this article. In

Section 3, the cohomology of Koszul–Vinberg algebras is introduced and double complexes are defined. In

Section 5, introductory material on spectral sequences is provided. Finally, in

Section 6 the special case of statistical manifolds is investigated. New results about inclusion of the de Rham complex in a double complex are obtained. Finally, a conclusion is drawn, highlighting relationships with K-theory and information geometry.

Notations and Writing Conventions

Throughout this document, the following conventions are applied: M is a smooth connected manifold; for a vector bundle , the notation , with as an open subset of manifold M, stands for the -module of the smooth sections over U. The functor defines a sheaf denoted by . Finally, is a shorthand notation for . Lowercase letters are used for sections, while uppercase ones are used for tangent vectors.

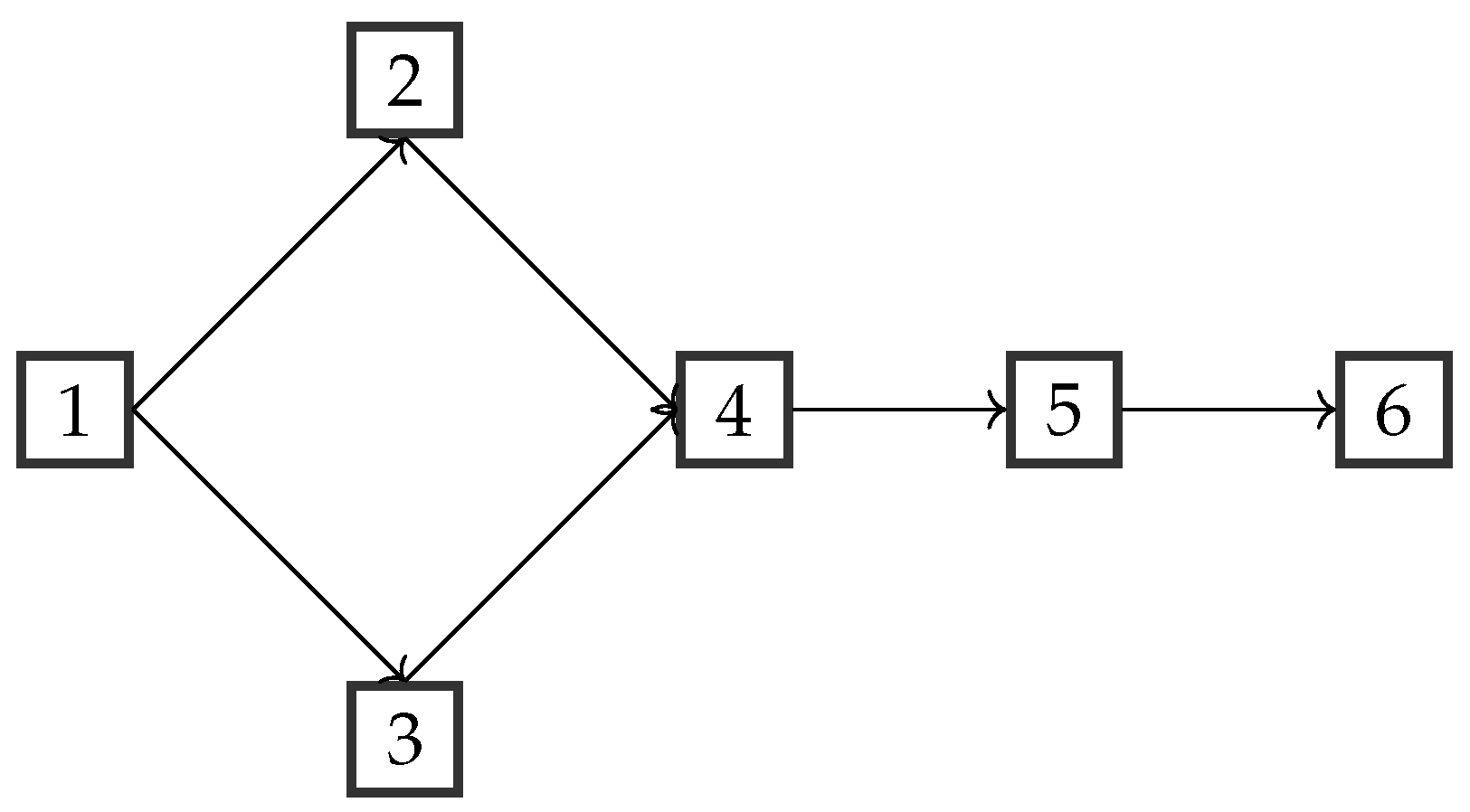

A reading diagram indicating dependencies between sections is provided in

Figure 1.

2. The Gauge Equation

Let

be a vector bundle. A Koszul connection ∇ is an

-linear mapping [

4]

such that

for any

. Let

be the bundle obtained by dualizing

E fiberwise. A section

, that is, a

-tensor, defines two bundle morphisms:

where

is such that

for any

:

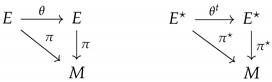

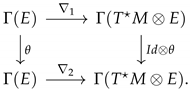

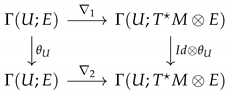

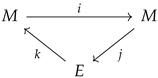

Definition 1. Let be a couple of Koszul connections. A -tensor θ is said to be a solution of the gauge equation if, for any ,or equivalently if the next diagram commutes: Definition 1 can be made local, giving rise to the following diagrams:

with

U being an open subset of

M and

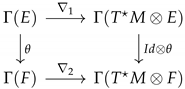

The above definitions can be generalized to arbitrary vector bundles over

M, giving rise to a category

whose objects are couples

, with

E being a vector bundle on

M, ∇ a Koszul connection on

E, and morphisms being bundle morphisms

such that

if the diagram

commutes.

Definition 2. Let be ∇

be an affine connection. Its dual is the affine connectiondefined by the relation Proposition 1. If θ is a solution of the gauge equation with connections , then is a solution of the gauge equation with connections .

Proof. For

,

□

Given a couple of connections

, the difference

is a section of

Using this, the gauge equation in Definition (1) can rewritten as

Considering

as an

O-form with values in

, Equation (

12) may be rewritten as

where

is the exterior covariant derivative associated with the connection

When

is flat,

. Thus,

Recalling that the Gauge group

is the set of bundle isomorphisms

then, given a connection ∇,

is also a connection.

Proposition 2. Let the triple be a solution of the gauge equation For any couple in , the tripleis a solution of a gauge equation. Proof. Starting with

,

Composing by

U to the left and

to the right yields the result. □

Proposition 2 indicates that the existence of a solution does not depend on a particular choice of frame–coframe to represent it. Furthermore, locally, it is always possible to assume a

of the form

as a pair

such that

has the reduced form of Equation (

17) exists by a standard linear algebra argument. Global reduction is not possible, however, as transition functions generally do not preserve the diagonal structure. Let

be the bundle

. The bilinear form

is non-degenerate, that is,

Proposition 3. A -tensor θ on E satisfies the gauge equation for a couple of connections if and only the bilinear formis parallel with respect to the connection Proof. Taking the differential yields

and symmetrically

Conversely, if

is

-parallel, then for any couple

,

Taking,

for example, with

being arbitrary, we have

proving that the couple

satisfies the gauge equation. □

The corollary below then immediately follows.

Corollary 1. The kernel of is -invariant; hence, the kernel of θ (resp. ) is (resp. ) invariant.

Proof. As the kernel of

B is

, if

then

and

Given a basis of

at a point

and subjecting it to parallel transport by

yields another basis of

at an arbitrary point

; hence, the claim is sustained. □

Remark 1. Corollary 1 implies by parallel transport that the dimension of the kernel of θ (resp. ) is a constant; hence, the rank of θ (resp. ) is also a constant.

Remark 2. The kernel of is the set of differential forms vanishing on the image of Thus, knowledge of the kernel of completely characterizes and In particular, θ has constant rank.

When there exists a Riemannian metric on the manifold M, the gauge equation can be specialized to pairs of connections on related by duality.

Definition 3. Let ∇

be an affine connection. Its conjugate with respect to g (often referred to as the dual connection) is the connection , defined by the relation Remark 3. The most common notation for the conjugate connection is In the present text, we adopt to distinguish it from the connection on

Definition 4. Let θ be a bundle morphism on Its conjugate, denoted , is the bundle morphism defined by Proposition 4. If is a unitary bundle isomorphism, that is, ifthen Proposition 5. Let ∇

be a connection and let U be a unitary bundle isomorphism. Then, Proof. If

U is unitary, so is

Let

; then,

and the claim follows. □

Proposition 6. If the triple satisfies the gauge equation , so does for any unitary isomorphism

Remark 4. If θ is normal, that is, if , and if the triple satisfies the gauge equation , then locally there exists a unitary isomorphism U such that is diagonal and satisfies a gauge equation. Again, this is a well known fact from linear algebra, as θ is locally diagonalizable in an orthonormal frame. As in the case of Equation (17), this is generally not true globally. Proposition 7. Using the musical isomorphisms we have Proof. For any

,

Passing to forms, for any

,

,

Now,

and the claim follows from identification. □

Proposition 8. Let the triple satisfy the gauge equation Then, the tensoris ∇

parallel. Proof. Tensor

in Proposition 3 can be written using the metric as follows:

Because is -parallel, the proposition follows. □

Remark 5. Defining a metric on bythe proof of Proposition 8 also shows that the tensoris -parallel. Proposition 8 has the important consequence that

can be split in two ways:

It is clear from Proposition 8 that if

is symmetric, that is, if

, then the tensor

is ∇-parallel. When

is skew-symmetric, i.e.,

, the same is true for

As in Equation (7), there is a category such that morphisms represent gauge equation solutions. The situation is nevertheless a little bit more complicated, as the dimension of the vector bundle may not agree. We recall the following well-known definition.

Definition 5. Let be a vector bundle. A pseudo-Riemannian metric on E is a smooth bilinear -mapping such that:

;

There exists an isomorphism ♭:

such that, for any ,

A pseudo-Riemannian metric is Riemannian if for any in

Definition 6. Let be two vector bundles on M equipped with respective Riemannian metrics A partial isometry from E to F is a bundle morphism U such that the following diagram commutes. Remark 6. Definition 6 is equivalent to the fact that, for any , we have Definition 7. Let be a partial isometry and let be a Koszul connection on F. Its dual is the connection on E defined by the relation Definition 8. The category has objects , with ∇ a Koszul connection on E and morphisms , where is a partial isometry, is a bundle morphism, and

The next two examples illustrate the gauge equation in simple situations.

Example 1. Take and consider the following symplectic 2-form:Let ∇

be a Koszul connection such that , let g be an arbitrary Riemannian metric on , and let be the dual of ∇

with respect to g; finally, let θ be the unique -tensor such that, for all vector fields , Example 2. Take , with ∇

as a torsion-less connection and g as a Riemannian metric. Any solution θ to the gauge equationis either 0 or invertible. 4. Statistical Manifolds

We recall that a statistical manifold is a quadruple

such that ∇ and

are dual connections with respect to the metric

g which are both torsion-free. These structures are of the utmost importance in information geometry [

10,

11], and are named after their appearance in statistical problems [

12].

In Hessian statistical manifolds, solutions of gauge equations give rise to statistical 2-webs, i.e., webs bearing the structure of a statistical manifold. These 2-webs are canonically associated with tensor products of co-chain complexes, the cohomology of which can be calculated with spectral sequences. Situations (I), (II), (III), and (IV) in Equation (

76) arise in any Hessian manifold

.

In this section, we retain the notation from

Section 2 and

Section 3 and fix a statistical manifold

Let

be a solution of the gauge equation

We define another pair of solutions

by the identities

All of the four distributions

are regular and are in involution. Furthermore, we have the following 2-webs:

where

These distributions are parallel with respect to ∇,

, as indicated by the identities

Here, the foliations

are Riemannian [

13,

14,

15].

Remark 9. If either or are Hessian manifolds, then K, , I, and are Hessian foliations. Thus, any of the pairs and gives rise to a double co-chain complex as in Equation (79). Any of the three distributions , , and is of constant rank. The three ranks may be different.

Remark 10. Note that a foliated manifold carries two other remarkable complexes in addition to its total de Rham complex, namely, the complex of foliated forms, and the complex of basic forms.

Assuming that

is a Hessian statistical manifold, we may construct two Koszul–Vinberg algebras

The two associated KV-complexes and are of particular interest.

Proposition 9. On the Hessian manifold , the Riemannian metric tensor g is a 1-cocycle of the scalar KV complex .

Corollary 2. In order for to be hyperbolic, it is necessary that . It is also sufficient if M is compact.

The next proposition makes use of the vector total KV complex to obtain a cohomological obstruction for a section to be a solution of the gauge equation.

Proposition 10. The gauge equation is equivalent to the cohomology equation Equation (

84) is essentially Equation (

14) rewritten; however, the vector KV complex is more tractable than the complex of

-valued forms.

4.1. Tensor Products

For every non-negative integer q, the dual vector spaces

and of

are denoted by

and b

, respectively, and we set

It makes sense to restrict the de Rham operation to

in order to define a cochain complex

In any Hessian manifold, we may use Remark 9 and the operators

,

to write the KV cochain complexes

and

as follows:

and

We note that the cochain Equation (

88) is then nothing other than

where

Remark 11. Similar complexes are attached to the three other distributions (I, , and ).

4.2. Double Complexes in a Hessian Manifold

Let be a Hessian statistical manifold. Two de Rham double complexes derive from the following 2-webs:

To investigate the properties of

, we can use the two Koszul–Vinberg algebras

and the complexes

Furthermore, we have the two double KV complexes

These double complexes give rise to the total complexes

, with

and

The operator

is defined by the relation

Mutatis mutandis, is defined in the same way.

Let

G be the group of symmetries of

; then,

G is the following finite dimensional Lie group:

The cohomology spaces of the complexes which are introduced above are geometric invariants of G.

4.3. Gauge Equation and Homology Persistence

Before proceeding with cohomology calculations, in this section we introduce useful materials derived from persistent simplicial homologies which are related to the gauge equation.

Let be a statistical manifold and let be a solution of the gauge equation of . According to the notation used in the preceding sections, gives rise to two 2-webs The foliation defined by is denoted by .

Let

be the rank of the distribution

. We set

Step 1.

We choose a

such that

and fix a point

. Let

be the leaf of

which contains

x. The

-dimensional submanifold

inherits the statistical structure (i.e.,

) from

Step 2.

We use the gauge equation of

to define

, obtaining the statistical submanifold

Setting

we can inductively construct the next statistical filtration:

In addition, we consider the real singular chain complex of

M:

The topology persistence

yields the following homology persistence:

5. Spectral Sequences

In this section, we briefly recall the definition of spectral sequences of co-chain complexes. A good recent reference on this subject is [

16].

Definition 11. A graded differential sheaf denotes a graded sheaf together with a graded morphism satisfying

Definition 12. The derived cohomology sheaf indicates the graded sheaf ()

: Remark 12. The derived cohomology sheaf is the sheafification of the local cohomology presheaf In the following, a ring R is fixed.

Definition 13. A bi-graded module E over R is a double-indexed collection of R-modules

Definition 14. Let E be a bi-graded module over R and let ; a differential over E of bi-degree is a double-indexed collection of R-morphisms such that

Definition 15. A differential bi-graded R-module is a couple , with E being a bi-graded module, d a differential of bi-degree , and r a fixed integer.

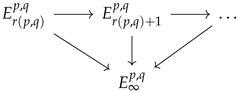

Definition 16. A cohomology spectral sequence is a sequence of bi-graded differential modules , where has bi-degree and for all .

Remark 13. A spectral sequence can be viewed as a successive approximation process; in most cases, is known and is the starting point of the sequence. Now, looking at stage n, that is, , the defining property of the spectral sequence indicates that if , then, as a bi-graded module, Now, if , there exist modules such that , . Thus, per Noether’s isomorphism, Furthermore, because is a differential, ; hence, Proceeding by recurrence, there exist limiting modulesand the purpose of the spectral sequence is to obtain Definition 17. A spectral sequence is said to converge if, for each couple of integers , there exists an integer such that all differentials are 0 for

Proposition 11. If a spectral sequence converges, then for any couple of integers , the module is isomorphic to the direct limit of the following diagram. Definition 18. An exact couple is a pair of modules and morphisms fitting in the following exact diagram. Proposition 12. Given an exact couple as in Definition 18, E is differential module with differential .

The next proposition can be found in [

16,

17].

Proposition 13. Let be an exact couple. The derived couple is exact with morphisms Passing to bi-graded modules and iterating the process defines a spectral sequence , where is the r-th derived module of E and

Finally, still using [

16], a filtered complex

defines an exact couple by passing to cohomology; that is, starting with the short exact sequence

we obtain a long homology sequence

Setting

we obtain an exact couple, that is, a spectral sequence. This construction is part of

Section 6, where our aim is to point out that relevant spectral sequences emerge from the methods of information geometry.

7. Conclusions

This article has presented the general gauge equation and its restriction to dual connections, introducing suitable categories the objects of which are gauge structures, that is, couples with E being a vector bundle on a base smooth manifold M and ∇ a Koszul connection. Within this frame, a morphism exists between two gauge structure if and only if a gauge equation is satisfied. This model will be investigated in a future work, especially in terms of its relationship with K-theory. In the present paper, equivalent formulations for the gauge equation are provided; moreover, two cohomological characterizations are provided in the case of flat connections, one arising from the covariant derivative on -valued forms and the other from the Koszul–Vinberg complex. Finally, when considering statistical manifolds for which a gauge equation is satisfied, a new inclusion of the de Rham complex into a double complex is obtained and appropriate spectral sequences defined.

In a future publication, we will consider the extension of this work to complex manifolds.