Abstract

The domination (number) of a graph , denoted by , is the size of the minimum dominating sets of , also known as -sets. As such, the dominion of G, denoted by , counts all its -sets. We proved a conjecture from one of the authors on the dominion of cycles and , . Further, we found the formulae and recurrence relations for the dominions of several grids, , with and other results when and . In general, domination and dominion play important roles in assessing certain vulnerabilities of any given network system.

MSC:

05C69; 05C85; 05C90

1. Introduction

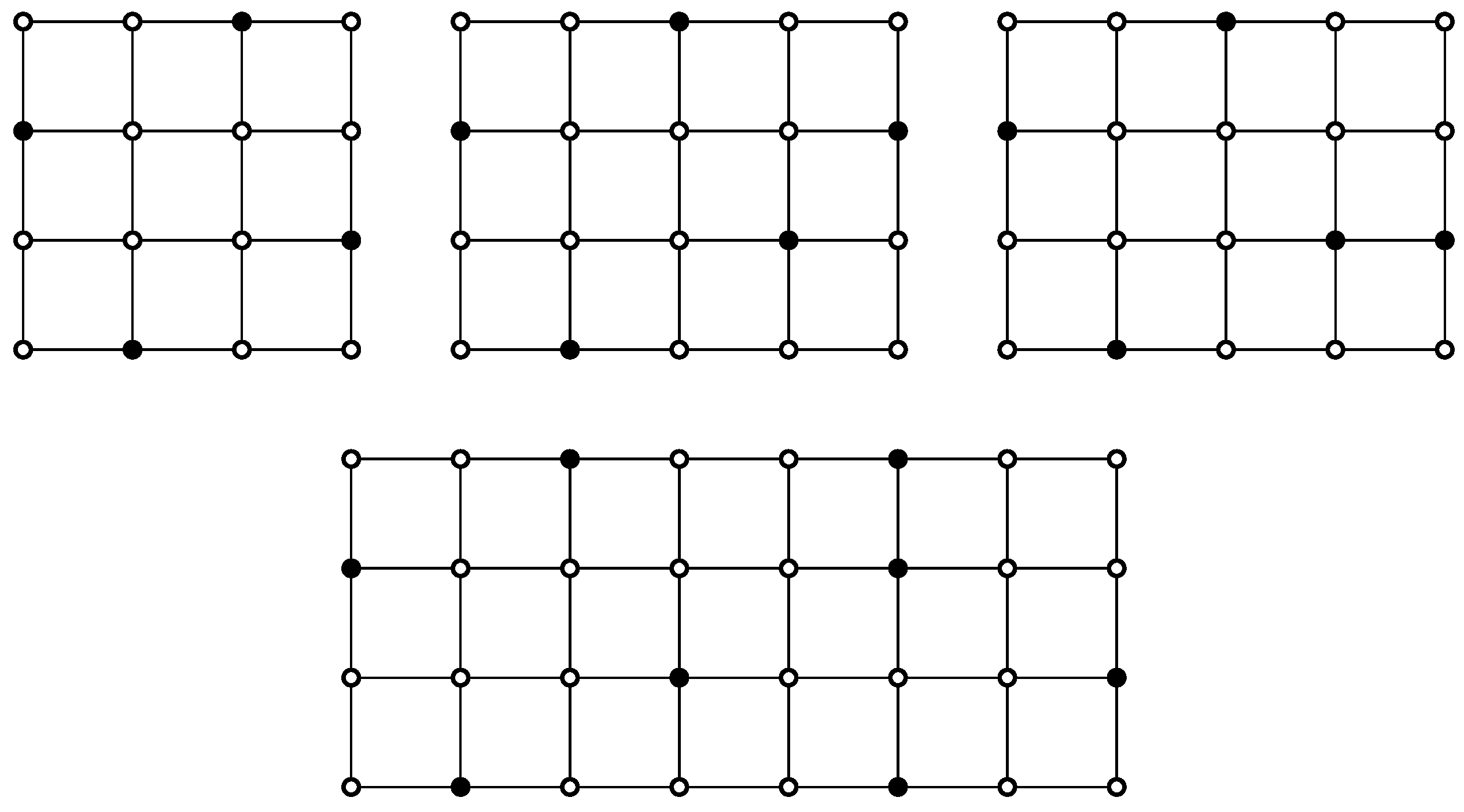

Throughout this article, the sequences of vertices denoted by and define a path and a cycle on and vertices, respectively. For other basic graph definitions, we refer the reader to [1]. A dominating set for a graph is a subset such that every vertex is either in S or has a neighbor . A dominating set S is a minimal dominating set if no proper subset is a dominating set. The domination number of a graph G is the minimum cardinality among all the dominating sets of G. Variations in minimum dominating sets have been extensively researched. We recommend to the reader Haynes et al.’s books [2,3] and several other research works [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] on their applications. For simplicity, they are referred to as γ-sets in [15], and a graph may have multiple -sets. Thus, the dominion (number) of a graph , denoted by , is the number of its -sets. Figure 1 illustrates an example of a graph with and .

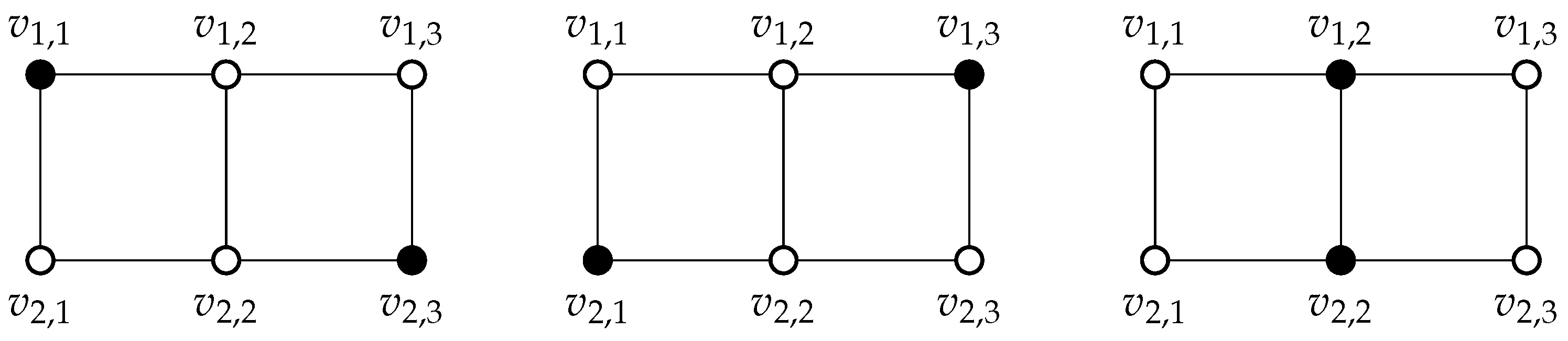

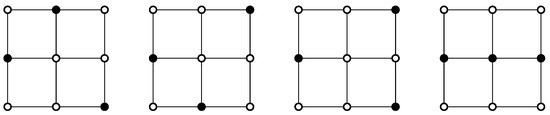

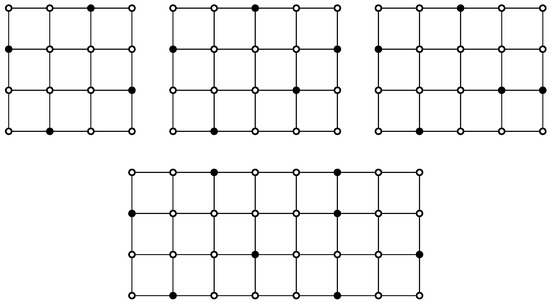

Figure 1.

Illustration of the (3) possible -sets (each with two elements in solid color) of the ladder .

In [16], Gray described several applications of the concepts of the dominion and domination of graphs related to wireless sensor networks, network security, social network analysis, distributed systems, and network optimizations. For instance, in network security, the domination of a network is the minimum number of nodes that need to be monitored to ensure the safety of the network system; as such, the critical assets within a network remain protected and the communications among these assets are not disrupted. Dominion, on the other hand, provides a network designer several different asset monitoring options in the event of a cyber attack. The greater the dominion value of a network system, the more resilient it is to any intrusion.

2. Results

2.1. Dominion on Paths and Cycles

Given a path and a cycle , it is well known that ; see [17], for instance. From this, the following result was established in [15].

Theorem 1.

If denotes a path on vertices, then, for , its dominions are

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- .

In this section, starting with the next lemma, we extend this result to cycles, which was a conjecture in [15]. First, we define as the number of -sets that contain v but do not contain its neighbor, i.e., any other vertex adjacent to v. Similarly, define as the number of -sets containing but not their neighbor.

Lemma 1.

Given a cycle on vertices, , the following relation holds

Proof.

Let and S be a -set. We will focus on all cases over . Note that no three consecutive vertices can be simultaneously in S. Hence, there are six cases. Three of them have two vertices in S, while the other three have one vertex in S.

Case 1. Suppose . Since no three consecutive vertices can be simultaneously in S, we have . The number of such -sets is .

Case 2. Suppose . Similar to Case 1, the number of such -sets is .

Case 3. Suppose and . If , then is covered as a neighbor and thus should not be in S due to minimality. Hence, . Similarly, . The number of such -sets is .

Case 4. Suppose and . The number of such -sets is .

Case 5. Suppose and . If , then the number of such -sets is . If , then the number of such -sets is . The total in this case is .

Case 6. Suppose and . This result is similar to Case 5.

From Cases 1–6, the result follows. □

We now restate Conjecture 2.1 from [15] as the next theorem.

Theorem 2.

If denotes a cycle on vertices, then, for , its dominions are

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

Proof.

Let and let , and for the values of please see Theorem 1.

Case 1. This case is proved in [15]. In the context of this article, we present another proof of the result.

By definition, refers to -sets that contain but not its neighbor. By removing , , from , we have a path on vertices. Hence, =1. Additionally, we have and . By Lemma 1, we have .

Case 2. Similar to Case 1, we have , , and . By Lemma 1, we have .

Case 3. Following a similar argument as in the previous case, we have , , and . By Lemma 1, we have

□

2.2. An Optimization Problem

This section considers grid graphs, or grids, for simplicity. An grid has the vertex set with two vertices and that are adjacent if and or if and . The special case is well known as a ladder; see Figure 1 for an example. We denote the cardinality of minimal dominating sets in and the cardinality of -sets. Please refer to [17] for some original values of .

We first consider the following combinatorial optimization problem.

Definition 1.

For and , minimize given the following (5) restrictions:

- 1.

- For , .

- 2.

- For , if , then .

- 3.

- If , then .

- 4.

- If , then .

- 5.

- If , then .

Let be the minimum sum of under the above restrictions. Then, .

For easier reference, we call this optimization problem the Dominion Optimization Problem.

Lemma 2.

Let be a vector that minimizes in the Dominion Optimization Problem. If , then for all i.

Proof.

The statement is trivial when .

For , we have . If , then and thus . Hence, . Similarly, . Thus, .

For , we have . If , then and thus . Hence, . Similarly, . If , then . Hence, . Therefore, . □

Definition 2.

From the Dominion Optimization Problem, if is a vector that minimizes and there exists k such that minimizes and minimizes , then we say is decomposible. We say can be decomposed to and . If is not decomposible, we say it is non-decomposible.

Lemma 3.

Let be a vector that minimizes in the Dominion Optimization Problem. Then, each of the following conditions implies that can be decomposed to and .

- 1.

- Both and satisfy the five restrictions in the Dominion Optimization Problem.

- 2.

- and .

- 3.

- .

- 4.

- and .

- 5.

- and .

Proof.

We just need to verify that all five restrictions in the Dominion Optimization Problem are satisfied for both and for each case.

It is straightforward to verify that the first four restrictions are inherited for each case. Additionally, restriction 5 is also satisfied due to minimality. Hence, we have the statement. □

Lemma 4.

Let be a vector that minimizes in the Dominion Optimization Problem. If is non-decomposible, then the values of each element alternate between zero and non-zero values.

Proof.

This follows from parts 2 and 3 of Lemma 3. □

Lemma 5.

If and is non-decomposible, then

or .

Proof.

Assume that . Since is non-decomposible, by Lemma 4, its values must alternate between zero and non-zero. If it starts with zero, then and it starts with . Since , we have and it starts with . Since , we have . By part 4 of Lemma 3, it is decomposible, which is a contradiction. Thus, does not start with zero. By a similar argument, it does not end with zero either. It follows that it starts and ends with non-zero elements. To minimize the sum, we have . □

2.3. Dominion on Ladder Graphs

Definition 3.

Given a grid with and , let S be a minimum dominating set. For , let be the number of vertices from both S and Column i. Then, satisfies the five restrictions in the Dominion Optimization Problem. In this case, we call the minimum dominating vector.

Lemma 6.

Let and be a vector that minimizes in the Dominion Optimization Problem. Let .

- 1.

- 2.

- If n is odd, then is non-decomposible.

- 3.

- If n is even and , then can be decomposed to two non-decomposible vectors and for some odd integer k.

Proof.

For , note that there is exactly one dominating set with dominating sequence . There are exactly two dominating sets with dominating sequence .

Case 1. If n is odd, then, since the sum of is , we have . If n is even, consider a sequence with and the rest . The sum is . Hence, . Since decomposition requires a non-smaller sum, we have .

Case 2. Suppose that n is odd. Then . Assume on the contrary that can be decomposed to and for some k. If k is even, then , contradicting . Similarly, if k is odd, then , which is again a contradiction. Therefore, is non-decomposible.

Case 3. Suppose that n is even and . Then, . By the contrapositive statement of Lemma 5, is decomposible. Suppose that it can be decomposed to and for some k. If k is even, then , contradicting . Hence, k is odd. To obtain minimal sum, both and are non-decomposible. □

Theorem 3.

Proof.

Let S be a minimum dominating set and be the corresponding minimum dominating vector.

If n is odd, then, by Lemma 6, is non-decomposible. For , by Lemma 5, we have . There are exactly two such minimum dominating sets. Hence, . For , could also be . Hence, .

Now, suppose that n is even. For , any set of two vertices cover all the vertices. Hence, . Now, suppose that . Then, by Lemma 6, can be decomposed to two non-decomposible vectors with length of odd integers, say and . Hence, . There are sets of non-negative odd integer solutions. For , we have or and thus . For , we have and thus . Now, suppose . Then, . □

We note here that a proof of a partial result from Theorem 3 first appeared in [16], albeit using a very different technique.

2.4. Dominion of Grid Graphs

Lemma 7.

Let and be a vector that minimizes in the Dominion Optimization Problem. If , then there exists an integer k such that .

Proof.

Let . If , then and all elements are 1. For the case of , we define . Now, we suppose .

If there exists an index j such that and , then, by Lemma 3, can be decomposed to and . If both and , then all elements in the vectors are 1. Hence, . However, by setting and the rest to be 1, we obtain , which is a contradiction. Hence, or . We can prove the statement by demonstrating that it works for one of the sub-vectors with elements. We may assume that .

We may further assume that is non-decomposible. Hence, by Lemma 4, the values alternate between zero and non-zero elements. If , then and thus it begins with . By Lemma 3, it is decomposible, contradicting the assumption. Hence, . To minimize , we have . If , then, to minimize , we have and thus . We now assume . Then, . If , then and thus , contradicting . Hence, and thus . □

We note here that it is shown in [17] that for all .

Lemma 8.

Let and . Let be a vector that minimizes in the Dominion Optimization Problem. Let . Then,

- 1.

- , and

- 2.

- can be obtained from a vector of length by inserting copies of .

Proof.

For , we have . Hence, the statement is true for . We may now assume . Then, by Lemma 7, there exists a sub-vector . Since , we have and . Hence, we can remove this sub-vector to obtain a vector of length . Let be the minimum value and define . Then, . Let with . Then, recursively, we obtain .

Consider a vector beginning with k copies of and the rest to be 1; we obtain . Hence, . By reversing the process, we see that can be obtained from a vector of length by inserting copies . □

Theorem 4.

Given an integer and let be a grid graph. Let be a minimum dominating vector of . Then, minimizes in the Dominion Optimization Problem and .

Proof.

It is straightforward to verify that satisfies all five restrictions of the Dominion Optimization Problem. Since the corresponding vertex set is a dominating set, we have . By Lemma 8, is the minimum sum of in the Dominion Optimization Problem. Hence, minimizes in the Dominion Optimization Problem. □

Given a grid graph , we define , the number of -sets that contain . Note that, by this definition, it is possible for such -set to contain its neighbors, such as and .

The dominion number increases rapidly as the values of increase. We use recursive arguments to generate and prove the remaining results in this article. As such, we derived a Python program, shown in the last section of the paper, to calculate the dominion numbers for some of those cases.

Lemma 9.

Given an integer and a grid ,

- 1.

- for .

- 2.

- for .

- 3.

- for .

- 4.

- for

Proof.

Let S be a -set and be the corresponding minimum dominating vector.

Case 1. Note that . For , since begins with , we have . Recursively, we obtain .

Case 2. Note that . For , since begins with either or , we have . Recursively, we obtain .

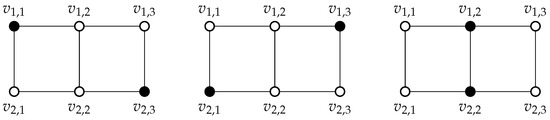

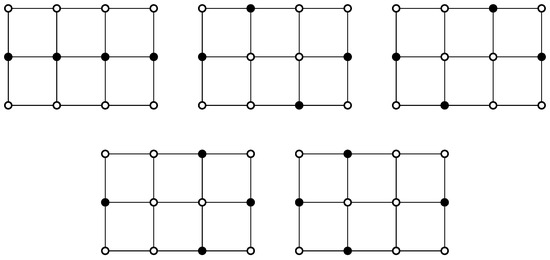

Case 3. For , since begins with , or , we have . Recursively, we obtain . It can be verified by the Python program in the last section that . All four such -sets are shown in Figure 2. Hence, .

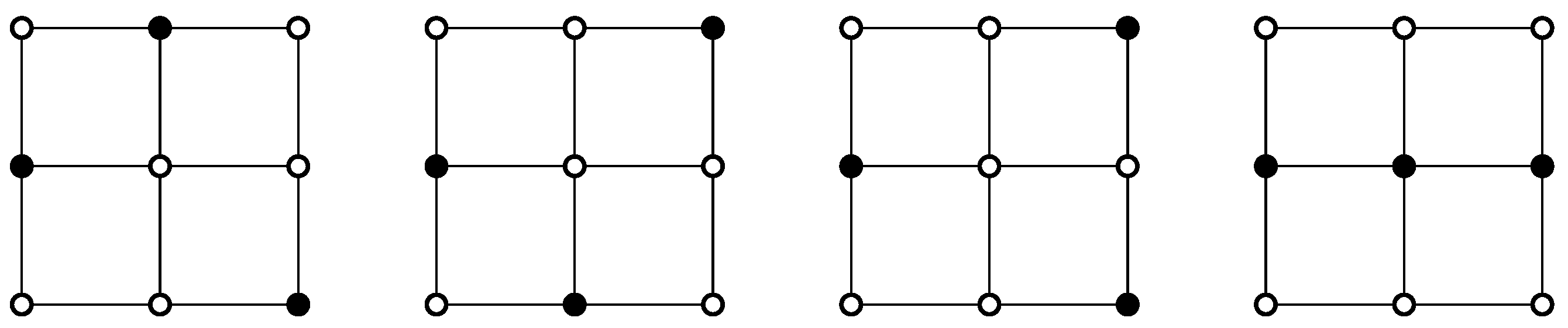

Figure 2.

All (4) possible -sets, including of the grid graph .

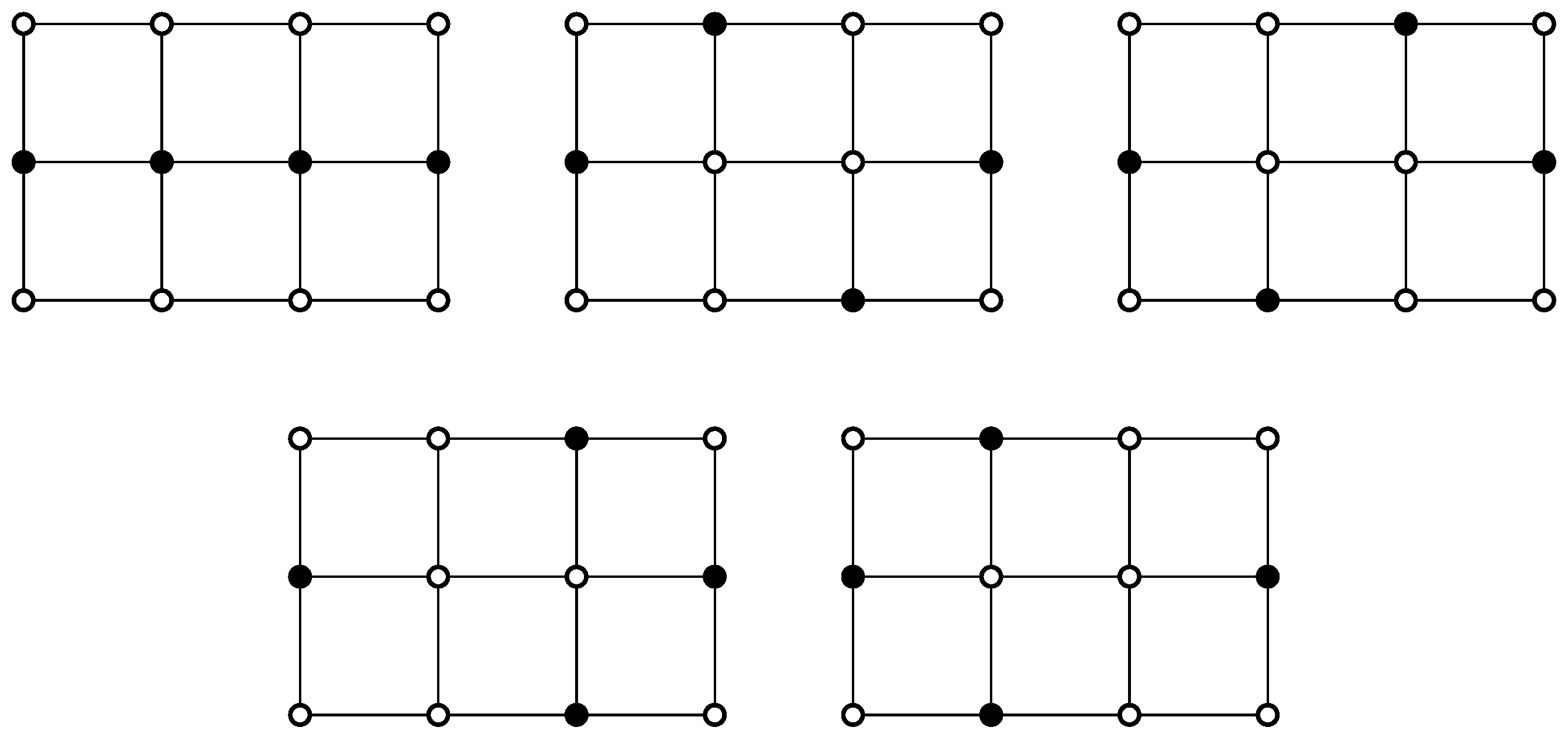

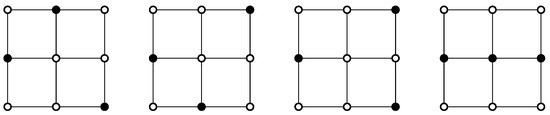

Case 4. Note that begins with , , , or . Note that contains both and . There are (5) such -sets, as shown in Figure 3. Hence, for , we have . Recursively, we obtain . It can be verified by the Python program in the last section that . Hence, .

Figure 3.

All (5) possible -sets, including both and of the grid graph .

□

Theorem 5.

Given and a grid .

- 1.

- If , then .

- 2.

- If , then .

- 3.

- If , then .

- 4.

- If , then

Proof.

Let S be a -set and be the corresponding minimum dominating vector.

Case 1. Since begins with , the vertex in S from Column 1 has to be . Hence, .

Case 2. If begins with , then . Otherwise, it ends with . By reversing the sequence, we can see that the vertices are uniquely determined and that . Hence, .

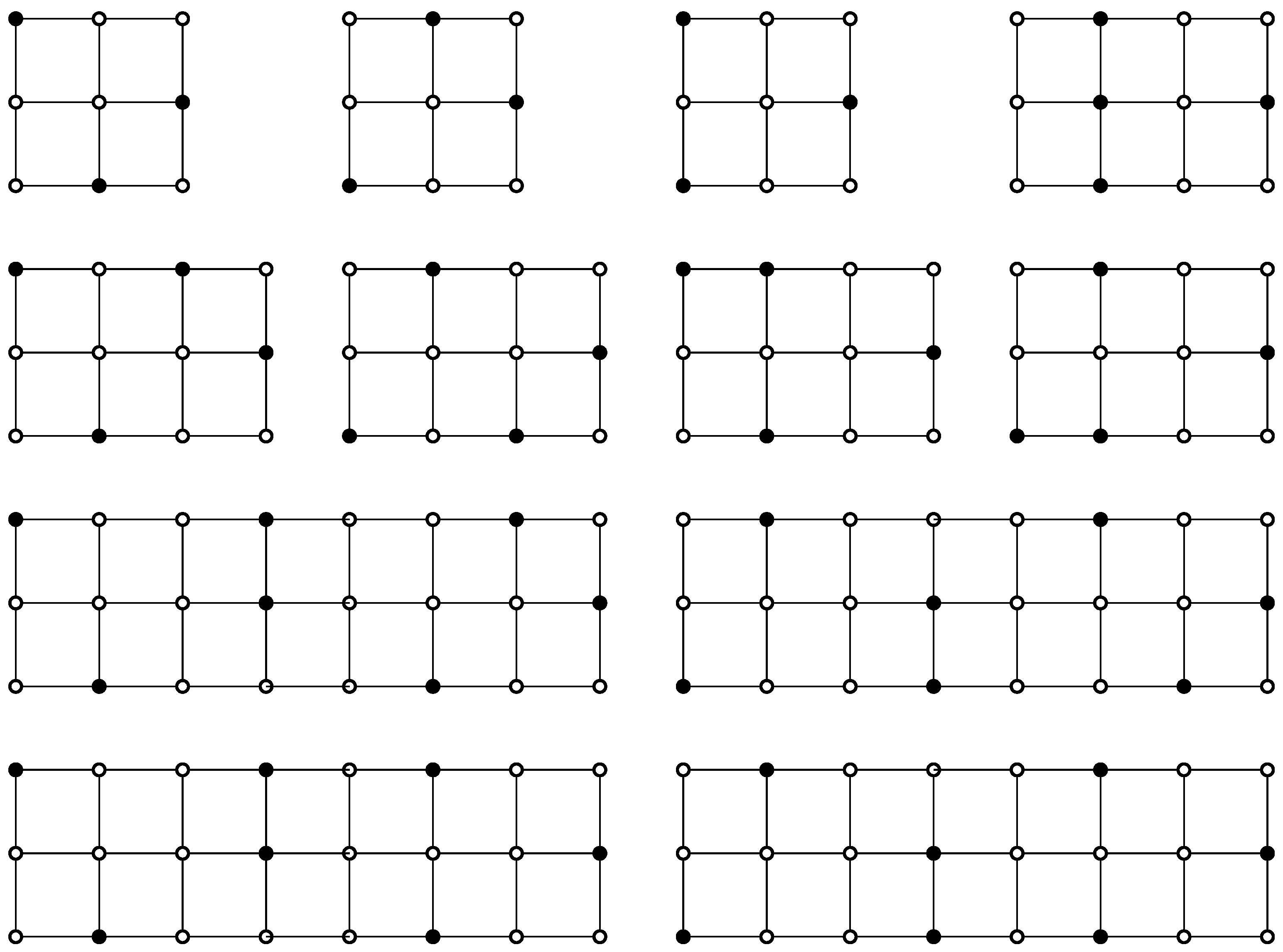

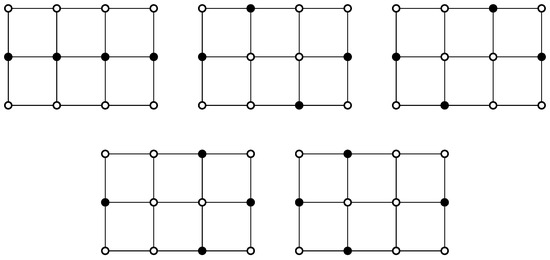

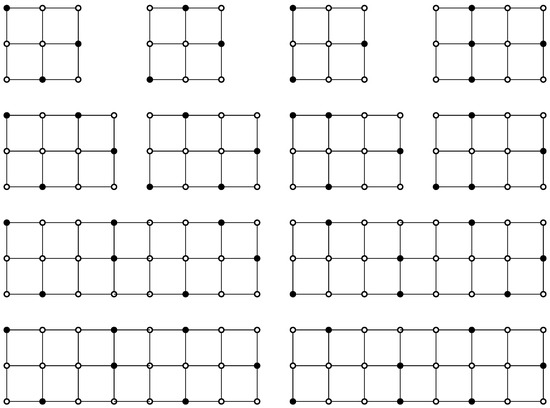

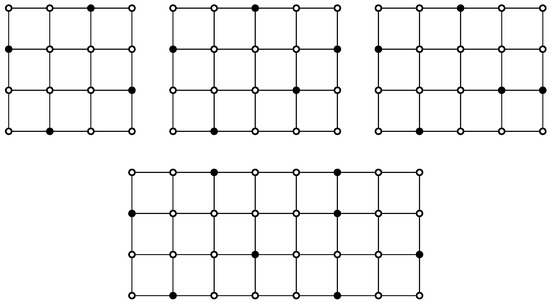

Case 3. For and , the results can be verified by the programming results in the last section. We only focus on . Consider the sequences that begin with such that and . There are 3 such -sets, as shown in Figure 4. Hence, .

Figure 4.

All -sets of grids as leading subset ending with the middle vertex in the last column.

Case 4. Similar to the previous case, we only focus on . Based on the above case, there are 3 sequences beginning with such that and . As listed in Figure 4, there are 5 cases beginning with and 4 cases beginning with . Hence, = . □

2.5. Dominion on Grids

This section considers the grids .

Lemma 10.

Given an integer , let be a vector that minimizes in the Dominion Optimization Problem. Then, contains only copies of sub-vectors and .

Proof.

The result follows if there is no 0 element. We assume there exists 0 in . We just need to show that every 0 in the vector belongs to some sub-vector . We will show that this happens to the first 0 and then the rest follows recursively.

Suppose that k is the first index such that . Note that is not allowed or it will lead to , which can be replaced with for a smaller sum. Hence, . If , then or can be replaced with for a smaller sum. Hence, . If , then and thus can be replaced with for a smaller sum. We now assume . Hence, . If , then can be replaced with for a smaller sum. Hence, and . By a similar argument, we have and . In this case, can be replaced with with a smaller sum. Therefore, and the result follows. □

Given a grid , we define as the number of -sets that contain n vertices.

Lemma 11.

Given a grid with a γ-set S, we have

- 1.

- or

- 2.

Proof.

Case 1. Note that the corresponding dominating vector cannot begin with and thus it begins with . If , then there is no way to cover both and . So, . Similarly, . Hence, or .

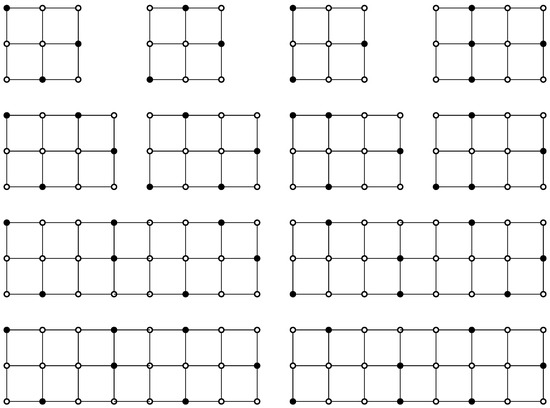

Case 2. Note that , , and . Hence, for , we have . It follows that for . We may assume . Note that the first graph in Figure 5 is the smallest -set that contains . By symmetry, there is another one that contains . These are the only two -sets with . Hence, and for . Also, note that Figure 5 provides all possible leading graphs containing that end with or . Hence, we have .

Figure 5.

Four graphs that provide the leading portion of -sets of the grid graph .

□

Theorem 6.

Given a grid graph , we have

Proof.

It is known in [17] that

From this result, we have if and . Further, using a Python program, we find the exact values for , , and and hence the result. □

3. Conclusions and Future Research

In this article, we proved a conjecture of one of the authors and found the dominions (formulae and recurrence relations) of several grids. In general, the notions of domination and dominion are important in ensuring the security of a network. They help network administrators to understand the vulnerabilities of a network and develop effective security measures to sustain an intruder’s attacks. The values of these two parameters, and , offer to network administrators an analysis of the resilience of a network. Still, we found it very tedious to determine the values of grids for larger . With a Python algorithm, we derived several exact values for and . Table 1 and Table 2 summarize these results. From these results, follow the next conjecture.

Conjecture 1.

If denotes the dominion of a grid , then the following hold:

- (a)

- (b)

- for

- (c)

- for

Table 1.

Dominion numbers with .

Table 2.

Dominion numbers with .

We derived the Python program for the paper as follows. We defined the function Gamma(m,n) based on the function result from [17]. We defined the function dom_vec(m,n) to generate all the potential minimum dominating vectors. We also defined Zeta(m,n) as the function found in the article and used it to generate Table 1 and Table 2. Finally, we defined Zeta3p(n) to represent , which was later used to find and in the proof of Lemma 9.

| import itertools as it |

| def Gamma(m,n): if m>n: m,n = n,m match m: case 1: return (n+2)//3 case 2: return (n+2)//2 case 3: return (3*n+4)//4 case 4: if n in (5,6,9): return n+1 else: return n case 5: if n==7: return (6*n+6)//5 else: return (6*n+8)//5 case 6: if n%7==1: return (10*n+10)//7 else: return (10*n+12)//7 case 7: return (5*n+3)//3 case 8: return (15*n+14)//8 case 9: return (23*n+20)//11 case 10: if n not in (13,16) and n%13 in (0,3): return (30*n+37)//13 else: return (30*n+24)//13 case 11: if n in (11,18,20,22,33): return (38*n+21)//15 else: return (38*n+36)//15 case 12: return (80*n+66)//29 case 13: if n%33 in (14,15,17,20): return (98*n+111)//33 else: return (98*n+78)//33 case 14: if n%22==18: return (35*n+40)//11 else: return (35*n+29)//11 case 15: if n%26==5: return (44*n+27)//13 else: return (44*n+40)//13 case _: return (m+2)*(n+2)//5-4 |

| def dom_vec(m,n): if n==1: yield [Gamma(m,1)] return seq = [0]*n def isValid(seq): if len(seq)==n: if sum(seq)!=Gamma(m,n): return False if 3*seq[-1]+seq[-2]<m: return False if len(seq)==2 and 3*seq[0]+seq[1]<m: return False if len(seq)>=3 and seq[-3]+3*seq[-2]+seq[-1]<m: return False if sum(seq)+Gamma(m,n-len(seq)-1)>Gamma(m,n): return False return True k = 0 while(k>=0): if k==n and isValid(seq): yield seq if k==n or seq[k]==m+1: k-=1 seq[k]+=1 else: if isValid(seq[:k+1]): if k<n-1: seq[k+1]=0 k+=1 else: seq[k]+=1 |

| def Zeta3p(n): m=3 def cnt_dom(seq,i=0,cov=(),nc=()): # tc for “to cover”; nc for “not covered” if i==len(seq): if len(nc)==0: return 1 else: return 0 cnt = 0 if len(nc)>seq[i]: return 0 for idx in it.combinations(list(set(range(m))-set(nc)),seq[i]-len(nc)): if i==0 and 1 not in idx: continue ncov = list(set(range(m))-set(cov)) for j in idx+nc: if j in ncov: ncov.remove(j) if j+1 in ncov: ncov.remove(j+1) if j-1 in ncov: ncov.remove(j-1) cnt += cnt_dom(seq,i+1,idx+nc,tuple(ncov)) return cnt cnt=0 for seq in dom_vec(m,n): cnt += cnt_dom(seq) return cnt |

| def Zeta(m,n): if m>n: m,n=n,m def cnt_dom(seq,i=0,cov=(),nc=()): # tc for “to cover”; nc for “not covered” if i==len(seq): if len(nc)==0: return 1 else: return 0 cnt = 0 if len(nc)>seq[i]: return 0 for idx in it.combinations(list(set(range(m))-set(nc)),seq[i]-len(nc)): ncov = list(set(range(m))-set(cov)) for j in idx+nc: if j in ncov: ncov.remove(j) if j+1 in ncov: ncov.remove(j+1) if j-1 in ncov: ncov.remove(j-1) cnt += cnt_dom(seq,i+1,idx+nc,tuple(ncov)) return cnt cnt=0 for seq in dom_vec(m,n): cnt += cnt_dom(seq) return cnt |

Author Contributions

J.A. and J.S.: Conceptualization, writing—original draft; S.G., O.M. and W.G.: investigation, analyses, and validation; E.E.: formulation, review, and editing; J.A.: corresponding author, supervision; S.G.: funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The researchers acknowledge the contribution of one of the authors’ former students, Erin O. Gray, to the first draft of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U.S.R. Graph Theory with Applications; North-Holland: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, T.W.; Hedetniemi, S.T.; Slater, P.J. Domination in Graphs: Advanced Topics; Chapman and Hall/CRC Pure and Applied Mathematics Series; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, T.W.; Hedetniemi, S.T.; Slater, P.J. Fundamentals of Domination in Graphs; Chapman and Hall/CRC Pure and Applied Mathematics Series; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, H.K.; Reza, E.A. Application of dominating sets in wireless sensor networks. Int. J. Secur. Its Appl. 2013, 7, 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Boutrig, R.; Chellali, M. A Note on a Relation Between the Weak and Strong Domination Numbers of a Graph. Opusc. Math. 2012, 32, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaluvaraju, B.; Chellali, M.; Vidya, K.A. Perfect k-domination in graphs. Australas. J. Comb. 2010, 48, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cockayne, E.J.; Dawes, R.M.; Hedetniemi, S.T. Total domination in graphs. Networks 1980, 10, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domke, G.S.; Hattingh, J.H.; Henning, M.A.; Markus, L.R. Restrained domination in trees. Discret. Math. 2000, 211, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggas, F. Decomposition and Domination of Some Graphs: Data Structures and Algorithms. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harary, F.; Haynes, T.W. Double domination in graphs. Ars Comb. 2000, 55, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, M.A. A survey of selected recent results on total domination in graphs. Discret. Math. 2009, 309, 32–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, M.; Stout, Q.F. Perfect Dominating Sets; University of Michigan, Computer Science and Engineering Division, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, D.J.; Strogatz, S.H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 1998, 393, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Yang, Y.; Ma, M. Minimum Connected Dominating Set Algorithms for Ad Hoc Sensor Networks. Sensors 2019, 19, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allagan, J.; Benkam, B. Dominion of Some Graphs. Int. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2021, 16, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, O.E. Dominion on Ladders. Master’s Thesis, Elizabeth City State University, Elizabeth City, NC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alanko, S.; Crevals, S.; Isopoussu, A.; Östergård, P.R.; Pettersson, V. Computing the domination number of grid graphs. Electron. J. Comb. 2011, 18, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).