1. Introduction and Statement of the Main Result

The rigid differential systems in the plane

with a focus or a center at the origin of coordinates can be written in the form

where

is a smooth real function. Such differential systems have been studied by several authors; see, for instance, [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Gasull, Prohens and Torregrosa [

9] in 2005 classify the phase portraits of the rigid cubic polynomial differential systems in the Poincaré disc.

Our objective here is to study the dynamics of the rigid polynomial differential systems with homogeneous nonlinearities of arbitrary degree in the Poincaré disc. From Equation (

1), a rigid polynomial differential system with homogeneous nonlinearities of degree

in the plane

can be written in the form

where

is a homogeneous polynomial of degree

.

Roughly speaking, the Poincaré disc

is the closed unit disc in the plane

, where its interior has been identified with the whole plane

and its boundary, the circle

, has been identified with the infinity of

. Note that in the plane

, we can go or come from infinity in as many directions as the circle

has points. A polynomial differential system defined in

can be extended analytically to the Poincaré disc

. In this way, we can study the dynamics of the polynomial differential systems in a neighborhood of infinity. In

Appendix A, we summarize how to work in the Poincaré disc.

Our main result is the following theorem and two propositions.

Theorem 1. The following statements hold for the differential systems (2). - (a)

If , then systems (2) have no limit cycles. - (b)

If , then systems (2) have at most one limit cycle. - (c)

Define . If and λ is sufficiently small, then n is odd and systems (2) have one limit cycle, stable if , and unstable if . - (d)

If and , then systems (2) have no periodic orbits.

Statements (c) and (d) were proved by Gasull and Torregrosa in Theorem 1.1 of [

7]. Here, we prove statements (a) and (b) at the end of

Section 2, and we present a new proof of statement (c).

Proposition 1. System (2) has a unique equilibrium point at the origin of coordinates. - (a)

If , then p is a focus, stable if , and unstable if .

- (b)

If and , then p is a center.

- (c)

If and , then p is a weak focus, unstable if , and stable if .

Statement (b) is also due to Gasull and Torregrosa; see again Theorem 1.1 of [

7]. We present another proof of statement (b).

Proposition 2. All points of the infinity of the differential system (2) are equilibrium points. - (a)

The infinite equilibrium point of the local chart in the Poincaré compactification of the differential system (2) is the α-limit (resp. ω-limit) of one orbit of system (2) if (resp. ). If , then, either the infinite equilibrium point is simultaneously the α-limit and ω-limit of two orbits of system (2), or no orbit has the infinite equilibrium point as the α-limit and ω-limit set. - (b)

The infinite equilibrium point of the local chart in the Poincaré compactification of the differential system (2) is the α-limit (resp. ω-limit) of one orbit of system (2) if (resp. ). If , then, either the infinite equilibrium point is simultaneously the α-limit and ω-limit of two orbits of system (2), or no orbit has the infinite equilibrium point as the α-limit and ω-limit set.

Propositions 1 and 2 are proved in

Section 2.

In the following propostions, we provide the phase portraits of the rigid quadratic polynomial differential systems.

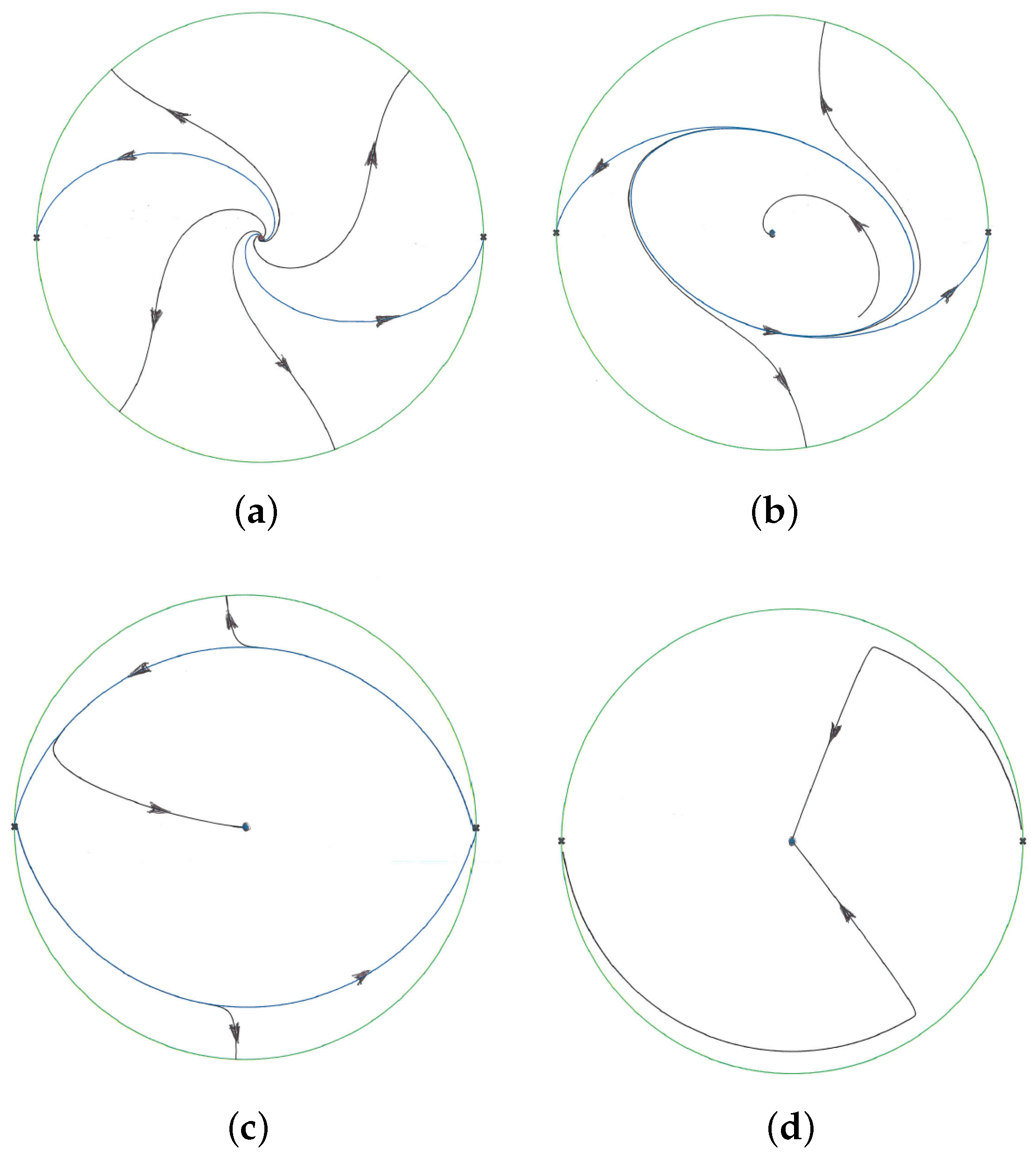

Proposition 3. The phase portraits of the rigid quadratic polynomial differential systems in the Poincaré disc are topologically equivalent to one of the two phase portraits of Figure 1, perhaps reversing the sense of all its orbits. Proposition 4. The following statements hold for the rigid cubic polynomial systems with homogeneous nonlinearities (2) with . - (a)

If , the origin is a global attractor; see Figure 2a. - (b)

An unstable limit cycle bifurcates from the origin when ; see this limit cycle for the value in Figure 2b. - (c)

The λ-family of unstable limit cycles ends in a graphic having two equilibria at infinity; see Figure 2c. - (d)

See the phase portrait of the system after missing the graphic in Figure 2d.

In what follows, we give more information about the references cited in this paper. In paper [

8], as in papers [

1,

2], the authors used commutators for studying rigid centers. In paper [

3], the centers of a family of cubic polynomial differential systems were studied. In books [

10,

11,

12,

13] are the results that we use in this paper. In papers [

4,

5,

6], the authors studied different polynomial differential systems with rigid centers. The authors of papers [

7,

9] studied the same rigid systems that we study, and in this paper, we comment on the differences of their results with our results. Reference [

14] is cited because there Poincaré introduced what we call now the Poincaré compactification for studying the dynamics of the polynomial differential systems in a neighborhood of infinity.

2. Proofs

For the basic notions of focus, center,

-limit,

-limit and limit cycle that appear in this paper see, for instance, book [

11].

We write the differential system (

2) in polar coordinates

where

and

, and we obtain the system

Taking

as the new time, the differential system (

3) becomes the differential equation

Proposition 5. Consider the differential Equation (4). - (a)

If , Equation (4) has the first integral - (b)

If denotes the solution of Equation (4) such that , then

Proof. Let

be an arbitrary solution of the differential Equation (

4). Since

the function

is a first integral of Equation (

4). Statement (a) is proved.

We verify that

is a solution of the differential Equation (

4) through the direct substitution of the expression of

, given in (

5), into the differential Equation (

4). Thus, statement (b) is proved. □

In the next proposition, we study the finite equilibrium points of the differential systems (

2).

Proof of Proposition 1. Since

, it follows that

p is the unique equilbrium point of system (

2).

The eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix of the system at

p are

. If

, by the Hartman–Grobman Theorem (see, for instance, [

10], or Theorem 2.15 of [

11]),

p is a focus, stable if

, and unstable if

. Thus, statement (a) is proved.

If

, from statement (b) of Proposition 5, the solution

of Equation (

4) becomes

Then,

From (

6) and (

7), it follows that

if and only if

. Thus, statement (b) follows. If

, then from (

6) and (

7), if follows that we have a weak focus, unstable if

, and stable if

, and hence statement (c) is proved. □

Now, we study the infinite equilbrium points of the differential systems (

2). For studying these equilibrium points, we shall use the notation and results of

Appendix A.1. Thus, we recall that for analyzing the local phase portraits at the infinite equilibrium points, we only need to study the infinite equilibrium points of the local chart

and the origin of the local chart

.

Proof of Proposition 2. From

Appendix A.1, the differential system (

2) in the local chart

is written as

Therefore, all the points

of the infinity contained in the chart

are equilibrium points. Rescaling the time, we eliminate the common factor

v between

and

, and we obtain the differential system

So,

. From here statement (a) follows.

In the local chart

, system (

2) is written as

Therefore, the origin

of the chart

is an equilibrium point. Consequently, all the points of the infinity are equilibrium points. Again, rescaling the time, we eliminate the common factor

v between

and

, and we obtain the differential system

So,

. This proves statement (b). □

After determining the local phase portraits at the finite and infinite equilibrium points of the differential system (

2), in order to obtain the global phase portraits in the Poincaré disc of this differential system, we need to control their possible limit cycles. Of course, if

, it is clear that the differential systems (

2) have no limit cycles. Now, we shall prove that when

, the differential systems (

2) have no periodic orbits, and, consequently, no limit cycles. First, we recall the following well known result.

Proof of Theorem 1. When

, since the first integral

given in statement (a) of Proposition 5 is defined in the whole plane

except at the origin of coordinates, the differential system (

2) cannot have limit cycles; otherwise, by continuity, the first integral will be constant in a neighborhood of the limit cycle, and this is not the case for the function

. This proves statement (a).

From statement (b) of Proposition 5, for every

, the solution

of the differential Equation (

4) such that

verifies that

If the solution

is periodic, then

. From this equation, we obtain the unique solution that

So, if there exists a periodic solution this is unique, consequently, it is a limit cycle. Statement (b) is proved.

Now, assume

. We have

if

p or

q is odd (see formulas 2.5111 and 2.5114 of [

12]), and

if

p and

q are even (see formulas 2.5121 and 2.5122 of [

12]). As usual

when

q is even. Therefore, since

and

is a homogeneous polynomial of degree

, it follows that

n is odd.

For completing the proof of statement (c), we shall use the averaging theory of first order; see

Appendix A.2.

Assume that

. Then, in the differential Equation (

4), we change the variable

r by

, and then we obtain the differential equation

If

is sufficiently small, we can apply the averaging theory of first order with

,

.

and

. Then

The unique positive zero of the averaged function

is

, and since

, from

Appendix A.2, it follows that the differential Equation (

8) with

sufficiently small has a stable limit cycle

such that

when

.

Now, assume

. Then, performing the change of variables

in the differential Equation (

4), and working as in the case where

, we obtain that the differential Equation (

8) with

sufficiently small has an unstable limit cycle

such that

when

. This completes the proof of the proposition. □

4. Conclusions

We have studied the dynamics of planar rigid polynomial differential systems with homogeneous nonlinearities of arbitrary degree. Thus, in Theorem 1, we have characterized when such a rigid system does or does not have a limit cycle, and the kind of stability of the limit cycle when it exists.

In this class of rigid systems, we have determined the local phase portraits of their finite and infinite equilibrium points in the Poincaré disc, in Propositions 1 and 2, respectively.

The phase portraits of the rigid quadratic polynomial differential systems in the Poincaré disc are classified in Proposition 3, while in Proposition 4, we provide the phase portraits in the Poincaré disc of one class of rigid polynomial differential systems with cubic homogeneous nonlinearities that can exhibit one limit cycle.

A nice objective for the future is to classify the phase portraits in the Poincaré disc of all rigid polynomial differential systems of degree 4; here, we classified the ones of degree 2, and in reference [

7], the ones of degree 3 were classified.