Abstract

In this paper, we study the properties of trajectories of systems of ordinary differential equations generated by the velocity field of a moving incompressible viscoelastic fluid with memory along the trajectories in a domain with multiple boundary components. The case of a velocity field from a Sobolev space with inhomogeneous boundary conditions is considered. The properties of the maximal intervals of existence of solutions to the Cauchy problem corresponding to a given velocity field are investigated. The study assumes the approximation of a velocity field by a sequence of smooth fields followed by a passage to the limit. The theory of regular Lagrangian flows is used.

Keywords:

systems of ordinary differential equations; Cauchy problems; multi-connected domain; Sobolev space; viscoelastic continuous medium; inhomogeneous conditions; regular Lagrangian flow MSC:

76A05; 35Q35

1. Introduction

Let , , be a bounded domain with a smooth boundary . Let the vector function = , , be the velocity field of a moving fluid filling . The trajectory of a fluid particle occupying a position at time is described by a vector function of a variable , which is the solution to the Cauchy problem for the ODE system

or, equivalently, the integral equation

Let function satisfy the condition , where is a given function defined on the boundary .

In the case of a smooth velocity field and identically equal to zero, the function on the boundary of (adhesion condition), and the solutions to the Cauchy problem (2) are defined for all and for all and . In this case, fluid particles do not leave the domain when moving.

At , the fluid can both flow into and flow out of through the boundary . In this case, the existence interval of a complete solution to the Cauchy problem (3) (see [1], Section I.3) can lie strictly inside , and it is important to know at what time moment a fluid particle occupying the position at time t begins motion in to the point x. Here, the function of the variables is defined as

The set defines the path of a given particle. If , then the motion of the particle along the path begins at the zero time moment, and either or .

Since the function means the time moment at which a fluid particle occupying the position at time t begins to move in to the point x, in the following, we call it the initial function.

If , then at that time moment the particle occupies position , and means the flow in moment of this particle into through .

There are various inhomogeneous problems with nontrivial function . As an example of such a problem, let us present the Jeffreys model of a viscoelastic incompressible fluid (see [2], Section 7.1).

The Jeffreys model (J) is represented by a dashpot (N) and a Maxwell model (M) connected in parallel (). In turn, the Maxwell model is represented by a dashpot and a spring (H) connected in series (−). Thus, the schema of the Jeffreys model reads as follows: .

A Jeffreys fluid is determined by a constitutive law

Here, is a substantial derivative, is the deviator of the stress tensor, = means the strain rate tensor, i.e., a matrix with coefficients , and and are some constants.

The integral form of (5) is

The substitution of (6) in the momentum equation

yields the problem

Here, = and are vector and scalar functions, respectively, which determine the motion velocity and pressure of the fluid. Function stands for a density of external forces. The divergence of a matrix is defined as a vector whose components are divergences of the matrix rows, , , and are constants characterizing the viscoelastic properties of a fluid, and are the specified initial and boundary values of the function u.

Note that the presence of the integral term in (8) means (see, e.g., [2] Ch. 7) that there is a memory along the trajectories of field u.

If boundary function , then field vanishes at the boundary . As mentioned above, the solution to the Cauchy problem (11) is defined over the entire interval (), and therefore, in (8).

The case was studied in [3,4,5]. A non-local weak and strong solvability for systems of the form (8)–(11) was established.

If on the boundary , then is defined at , where , which explains the presence of in (8).

The case of an inhomogeneous condition on the boundary of simply connected domain was studied in [6,7,8], where a weak solvability of (8)–(11) was established.

Usually, when studying the weak solvability of a problem of the (8)–(11) type it is assumed that . Therefore, the solvability of the Cauchy problem (11) becomes nontrivial because generally speaking, there is no classical solution to it.

It turns out to be convenient to understand the solution of problem (11) in the sense of the theory of regular Lagrangian flows.

The existence and uniqueness of the solution to (8) are guaranteed by the classical Cauchy-Lipschitz theorem. But if , the problem (8) has (non-unique) solution only for x from some dense subset of . The selection of such a solution, where the mapping conserves a measure, is encoded in the concept of regular Lagrangian flow (see Section 7 for details).

Accordingly, the study of the function included in the (8)–(11) system becomes more complicated.

The case of a domain with multiple boundary components is already much more complicated for the Navier-Stokes system (problem (8)–(11) with ). A survey of results on this problem can be found in [9].

A weak solvability of (8)–(11) for an inhomogeneous condition on the boundary of a multi-connected domain was established in [10].

The motivation for studying function is as follows.

One of the most effective tools in studying the weak solvability of problems of (8)–(11) type is the topological approximation method [2]. It consists in smoothing the nonlinear terms in (8) and (10) and data , , and f, and building a sequence of regularized problems which provide the solvability of these problems and convergence of their solutions , , and to u, z, and .

Since functions z and are determined by Cauchy problem (10), it is necessary that boundary conditions of functions yield in the limit.

But the usual smoothing of u and fails to provide the convergence to in the case of an inhomogeneous . The reason is the complex behavior of the trajectories in the vicinity of the touch points of to .

The reason is the presence of a tangent set for on . It turns out that a sufficient condition for the convergence of to is the “smallness” of tangent sets for .

The goal of the present paper is to construct approximations and of the fields u and which provide the convergence of to in the case of multi-connected , space , and , .

The paper is organized as follows. Section 1 and Section 2 are Introduction and Notations, respectively. In Section 3, the assumptions on domain and boundary function are given. In Section 4, approximations of the smooth function by a family of specific functions are constructed. In Section 4, approximations are constructed for . The properties of the initial function for smooth field u are studied in Section 5. In Section 6, the properties of function are investigated in a common case of a field u from a Sobolev space. In Section 7, necessary facts from the theory are given.

2. Notations

Notation stands for Sobolev spaces n times differentiable in vector functions, (see [11], Section II.1.5). Sign , , denotes the space of function traces from on .

The embedding is continuous. Symbol denotes the set of infinitely differentiable compactly supported maps of in .

Let . Denote by H and V the closure of in the norms of spaces and , respectively (see [12], Section III.1.4).

By , we denote the dual space of V.

We denote by the action of the functional f from the dual space of V on the function v from V. The identification of the Hilbert space H with its dual and Riesz’s theorem lead to continuous embeddings of .

For and , the relationship with a scalar product in H is valid.

Sign denotes the scalar product in Hilbert spaces , H, , and . It is clear from the context in which space the product is taken.

Norms in the space H and are denoted as , and in V as . Norms in the spaces are denoted as .

Norms in and are denoted as , norms in and as , and the norm in space as . The norm in the space is denoted as .

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Domain

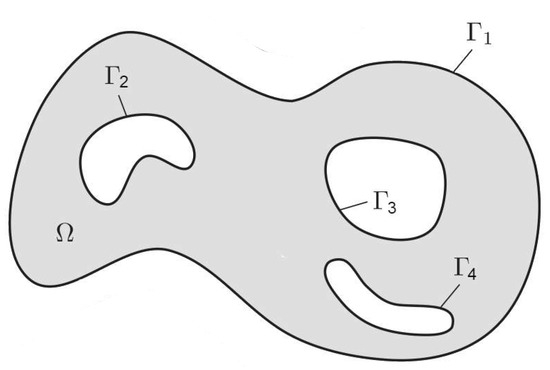

Let , be a family of bounded simply connected domains , , with the boundaries . Let , and , .

It is assumed that domain is obtained by removing from domain pairwise disjoint simply connected domains , .

Thus, the surface (curve) bounds from the outside, while the other connected components of the boundary , , lie inside this surface, so that (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Domain .

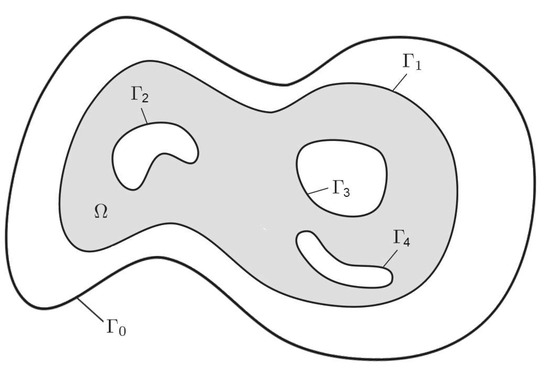

For technical reasons, we assume that is contained in some bounded domain with the boundary (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Domain .

It is convenient for us to assume that the boundary of the domain of is determined by the relation , where the function and for and for .

3.2. Boundary Function

We are interested in the velocity field of an incompressible fluid that flows in the domain and takes the value on . Here, is a given function. Thus, the function satisfies the following relations

From the continuity Equation (12), there follows that the function must satisfy the following condition

Here, is the unit outward normal to at point ,

The condition (14) means that the flux of the incompressible fluid across the boundary of the flow region is equal to zero.

Let

be the flux of the velocity vector u across each connected component of the boundary of .

By (14), it follows that

Since the behavior of the solutions to the Cauchy problem in (11) is closely related to the boundary function , we impose some conditions on .

From the inclusion it follows that for the trace of the function u on the boundary , the relation is valid.

Let us denote

Let us introduce the space

The function allows the continuation of a in such that in , on (see [9]), and the following inequality is true:

Denote by the operator that assigns to an arbitrary function the so constructed function , so that .

The function allows the continuation of into such that on and on (see [9]), and the following inequality is valid:

Denote by the operator that assigns to an arbitrary function the so constructed function , so that .

For an arbitrary function , the function is defined as for and at . Obviously, and

Denote by the operator that assigns to the function the so constructed function , so that .

Let

Obviously, . Note that the sets , , and can have a nonempty intersection with any part of the boundary .

If , then . This means that each component of the boundary belongs to either or . In the case of , the inequality takes place on , and is the outflow area of the fluid from . In the case of the condition takes place, which means is the inflow area.

3.3. Cauchy Problem

In the case when the velocity field u of the problem (8)–(11) belongs to the space , there is no classical solution to the Cauchy problem (11), generally speaking. Therefore, it is convenient to understand the solvability of the problem (8)–(11) in the sense of the theory.

However, the direct application of this theory is hindered by the presence of an inhomogeneous boundary condition for function u.

To make use of the theory, we extend function u from to the wider domain by some function vanishing on .

Let us build this function. Let be a given function and let u belong to and satisfy the boundary condition .

Therefore, can be represented as an element of the set of functions

Here, function a is the extension of from to by the ratio . The set is a hyperplane in .

Let function v of variables belong to the space . Extend function v from to to function by setting for and for . Denote the extension operator by , so that .

Obviously, if , then .

Now, let us define the function on as . Then, the function satisfies the following ratios

Along with problem (11), consider the auxiliary Cauchy problem

Since , we are in position to make use of the theory. Replacing by and making use of Theorem 5, we infer that there exists a unique z generated by the function . In particular, this means that the Cauchy problem (19) has an absolutely continuous solution with respect to for a.a. and .

The restriction of from to yields the solutions of the Cauchy problem (11).

The function is defined as

where is the generated by .

Denote by the operator that matches the function u with the function , so that .

4. Approximations of Functions from

The behavior of the trajectories z of a field u in the vicinity of a boundary depends significantly on the boundary function . Suitable approximations of provide the convergence of appropriate , , and to the solution u, z, and of original problem (8)–(11).

A complexity in the behavior of the trajectories , and as a consequence of , arises in a vicinity of the touch points of to . Therefore, the set of such points should be small enough.

Below, we build approximations , whose touch-point set consists of a finite number of smooth curves on in the case of or a finite number of points on in the case of . The use of trigonometric polynomials proves to be a convenient tool for this.

Denote by the set of smooth functions such that the set is either empty or consists of a finite number of smooth curves on in the case of and a finite number of points on in the case of .

Theorem 1.

Let . Then, for any there is a function such that the following inequality is true

Proof of Theorem 1 (case = 2).

In this case, the boundary of domain is , where are smooth closed curves.

Let us take a fixed . Obviously, the restriction of the function from to (let us keep the designation for the restriction) is such that .

Let the smooth function , , , define a parametrization of . Here, s means the distance along from to , and S is the length of the curve .

Represent the function in the form , where is the outward unite normal, and , , is the tangent vector at the point . Then, the scalar functions belong to the space .

Approximate the function by a function .

A change of variable converts function to function

The inclusion and the smoothness of imply the inclusion .

Denote by the set of smooth functions such that the set

is either empty or consists of a finite number of points on ].

Lemma 1.

Let . Then, for any , there is such a function that the following inequality is true:

Proof of Lemma 1.

We can (see [13], Section 2.1) approximate the functions , , by trigonometric polynomials , so that

Note that the set of zeros of the functions is finite. Therefore, .

Lemma 1 is proved. □

Let be the inverse to the map. A change of variable converts function to the smooth function

From the finiteness of the set of zeros of the function and the smoothness of , it follows the finiteness of the set of zeros of function = . Therefore, .

Denote

Let us introduce the function

Note that the set of zeros of the function and the set of zeros of the function are finite.

It follows from (23)–(25) that

Consequently,

Estimate . Making use of (25), one has

From (22) and (28), it follows that

A change of the variable yields

Further,

From (22), (24), and (30), it follows that

From (29), (30) and (33), it follows that

Now, we define the function on by the ratio

where on each is determined by the formula (25).

From inequality (34), for each , there follows the inequality

Let us show that belongs to the class .

Obviously, the finiteness of the set of zeros of the function implies the finiteness of the set of zeros of the function .

It remains to prove the equality .

Making use of (26), we have

Thus, the function belongs to the class .

From this and the relations (35) and (36), there follows the statement of Theorem 1.

Theorem 1 is proved in the case of . □

Proof of Theorem 1 (case = 3).

In this case boundary of the domain is , where are smooth surfaces.

We approximate the function by the function . Recall that in the case , the class consists of smooth functions such that the set is either empty or consists of a finite number of smooth curves on and a finite number of points.

Let us take a fixed surface . Consider the restriction of the function defined on to , while retaining the previous notation. Obviously, the inclusion implies the inclusion .

Denote by the set of smooth functions on such that the set consists of either a finite number of smooth curves on or is empty.

Lemma 2.

Let . Then, for any , there is a smooth function that satisfies the inequality

Proof of Lemma 2.

Consider the unit sphere

Let be a one-to-one smooth map, so that .

Let

and define a one-to-one smooth map as , , .

Define the map by the expression , , so that it is a smooth map.

Given function , define , . It is clear that , .

From the smoothness of the mappings and their inverses, it follows that .

Note that the function defined on allows a periodic continuation to due to the obvious relations and .

Approximate by a non-zero trigonometric polynomial (see [13], Section 2), so that

Due to the smoothness of the map r, the set of zeros of the function is either empty or may consist of a finite number of smooth curves, possibly intersecting, and a finite number of points.

Let be an arbitrary function, , . The smoothness of the maps r and implies the inequalities

for some .

The inequalities (38) and (39) imply the inequality (37).

Lemma 2 is proved. □

Let . Represent the function in the form

Here, the normal and tangent components of are defined as and , respectively, is the unit outward normal to at the point .

Consider the restriction of the function to the part of .

Making use of Lemma 2, we approximate the function by the function so that for a predetermined , there holds the inequality

Let function be defined on as having restrictions on each . Then, from (40), there follows

Approximate the vector function by the smooth function , so that the following inequality holds

Let . From inequalities (41) and (42), there follow the inclusion and the inequality

Let , . If , let us say , . Then, from (43), there follows

If , then consider the function

where is the area of . Let us show that the inequality (43) holds for this .

Using the form of , we have

Let us estimate the value of .

Using elementary calculations and inequality (43), we obtain

It follows from (45) that

Thus, .

We have shown that in the case of , the inequality (43) is valid for the function , and .

Now, define the function on by the expression for , . The inequalities (43) for , , imply the validity of the inequality (20).

It follows from the properties of the functions that and

Thus, and satisfies the conditions of Theorem 1.

Theorem 1 is proved. □

Remark 1.

From Theorem 1, it follows that an arbitrary function can be approximated by the sequence , , such, that the ratio holds. Let us move on to studying the properties of the initial function.

5. Initial Function (Case )

5.1. The Case of

Let , the condition (13) be satisfied on , and . Let us continue the function u in a smooth way from in so that the continuation of to vanishes. Then, .

Along with problem (3), consider the Cauchy problem

Since vanishes on and , the Cauchy problem (49) is uniquely solvable, and its solution is defined for all and is continuously differentiable on .

In accordance with (4), the initial function for solution to the Cauchy problem (49), we define the omitting index u by the ratio

The behavior of the function depends on the behavior of the boundary function on at the tangent points.

Theorem 2.

Let the set . Then, the function is continuous on .

Proof of Theorem 2.

Let . Denote , . Then, .

At first, consider the case when . In this case, . Otherwise, could be continued to the left of . Therefore, .

Since at and , then trajectory enters at point ,

and . Therefore, belongs to the set .

Consider the function . The ratio defines as an implicit function of variables . Indeed, it is not difficult to see that

Since the vector is proportional to the normal vector , then, by virtue of boundary condition (13) and the inclusion of , it follows that

Therefore (see [14], Section Ch. 9, p. 223), there exists the implicit function of variables which is continuously differentiable in the neighborhood of and even more continuous. It is clear that this function .

Now, let . In this case, either or . In the first case, by virtue of the condition of Theorem 2, belongs to the set , and the proof is similar to the one performed above.

Consider the case of . From the continuity of according to the initial data (see [1], Section V.2), it follows that there is such a small neighborhood U of the point that for , the solution of the Cauchy problem differs little from . Then, for , and therefore, is continuous at point .

Theorem 2 is proved. □

Let us now consider the case of a nonempty set . In this case, the function , generally speaking, is not continuous on . Let us give an example.

5.2. An Example of a Discontinuous Function

The continuity of the function does not guarantee the continuity of the function by . Let the domain be , .

Consider the Cauchy problem

or, equivalently, the integral Equation (3), where , .

Obviously, the Cauchy problem (51) is uniquely solvable for any .

Let , . Then, , where and , is the solution to the Cauchy problem (51).

Obviously, for and . This means that trajectory which comes out from at moment get on the boundary of the at moment . Therefore, for , .

Now, let , , where is quite small. Then, is a solution to the Cauchy problem (51) with the initial condition , . In this case, , and then for all . Therefore, for , .

Now, let us say , where is quite small. Then, is a solution to the Cauchy problem (51) with the initial condition . In this case, , since when decreasing function decreases while increases. Therefore, there is such a that when , and . Consequently, for , .

It is easy to show that for and , .

Thus, when tends to x on the left and right, the function has limits 0 and , respectively. Therefore, is discontinuous at the point for , .

Note that the unboundedness of the domain in this example is a technical point, and in the case of a bounded domain, it is not difficult to construct a similar example.

5.3. Case of a Nonempty

Let be the solution to the Cauchy problem (3). Consider the set

The set is the image of into by the mapping .

Since , then , where is the Lebesgue measure of the set in .

Let . Obviously, .

Theorem 3.

Let the set . Then, the function is continuous on .

Proof of the Theorem 3.

Let . Then, , and therefore, . Consequently, . The proof of the continuity of the function in the vicinity of a given point is carried out in the same way as in the proof of Theorem 2 in the situation .

Theorem 3 is proved. □

Let us move on to studying the properties of the initial function in the general case.

6. Initial Function (Case )

6.1. Approximations of the Velocity Field

Let and satisfy inhomogeneous condition (13) on boundary and condition (12). Represent u in the form , where , and is the continuation of from into .

Consider the set of functions:

Let u be an arbitrary function from W. Approximate function u by a sequence of smooth functions via approximations v and a.

Denote by the “Leray projector”, i.e., the orthogonal projector in onto the space H of divergence-free functions.

Consider the operator , which acts in H and is defined on the domain .

The operator A is a positively definite self-adjoint operator (see [15], Section 2.4) The orthogonal system of eigenvectors with eigenvalues forms an orthonormal basis in H.

Let , , . Represent function v in the form

where .

Then,

Consider the sequence of approximate functions :

where .

The following equalities are valid:

Then,

and the convergence is valid:

It follows from Theorem 1 that there exists a sequence such that → 0 as . Let . Then, as .

Denote by and the extensions of the functions and v, respectively, from to , and put

Obviously,

and

It follows from (58)–(59) that

for some constant , and the convergence is valid:

Along with the Cauchy problem (19), consider the Cauchy problem (19)

Since , then there are uniquely definable and generated by the functions and , respectively (see Theorem 5).

It follows from Theorem 6 that the sequence of converges (up to a subsequence) with respect to in -measure to generated by uniformly over t.

Then, there is a subsequence , which, for a.a. , converges to by uniformly over t.

Let us assume that this is the sequence itself.

Consider now the initial functions defined on

for the aforementioned and .

Find out some properties of the functions and .

6.2. Limit Function

Let . It follows from Section 6.1 that there are smooth approximations of the function u by the functions . Let , be a solution to the Cauchy problem (64).

First of all, we note that from (60), it follows that the function is continuous and differentiable on . Then, is a classical solution to the ODE system (64).

The continuous dependence of the solutions of the ODE system with respect to the initial data (see [1], Section V.3) implies the continuity of the function on .

It follows from Theorem 2 that for the function defined by relation (65), the following sentence is valid:

Lemma 3.

Let . Then, the function is continuous on .

Moreover, making use of Theorem 3, one obtains

Lemma 4.

Let . Then, the function is continuous on .

We make use of these statements to prove the following fact.

Theorem 4.

The sequence converges (up to the subsequence) to as at a.a. .

Proof of Theorem 4.

Since , . Consequently, , are continuous on the set , which is dense in .

From the convergence of the sequence to at a.a. , it follows that at a.a. , convergence takes place at a.a. . Let us choose such an x. Then, the sequence converges to at a.a. .

Let us show that then, converges to .

Suppose that and assume the opposite, i.e., does not converge to . Then, there is a subsequence (the indices are the same), in which either or for some .

First, let . Let us choose so that converges to . Then, when and , while and .

A passage to the limit in the last inequality yields , which cannot be.

Similarly, the case of is considered.

In the case , Theorem 4 is proved.

The case is proved more simply.

Theorem 4 is proved. □

Corollary 1.

The function . The measurability of follows from Theorem 4 and the boundedness is obvious.

7. Regular Lagrangian Flows

Here are the facts used above from the theory of (see, for example, [16,17,18]).

Definition 1.

Let , . Associated to u, a regular Lagrangian flow is the function , , which satisfies the following conditions:

(1) For a.a. x and any , the function is absolutely continuous with respect to τ and satisfies the equation

(2) For any and an arbitrary Lebesgue measurable set B, the relation is valid

(3) For all , and a.a.

Here, is a Lebesgue measure of the set B.

Let us recall some results on .

Theorem 5.

Let , . Then, there exists a unique z generated by v. Moreover,

Theorem 6.

Let v, , for some . Let the inequalities be fulfilled

Let converge to v in for . Let and be the s generated by and v, respectively. Then, the sequence converges (up to the subsequence) to z with respect to a Lebesgue measure on the set uniformly on .

For and , the trajectory belongs to the domain , unless , .

From the definition of the function , it follows that at , and when .

It is clear that for all , a.a. and , the function satisfies Equation (67).

Note that in the case of a smooth , the is a classical solution of the Cauchy problem (67).

8. Conclusions

The approximations of a divergence-free velocity field with an inhomogeneous condition on the boundary of a bounded multi-connected domain by a sequence of smooth fields were constructed. By this, the smooth trajectories of the fields were defined on the maximal intervals , where initial functions were continuously differentiable a.e. and and converged a.e. to the trajectories generated by the regular Lagrangian flow u and initial function of the field u, respectively.

A commonly used method for solving systems of type (8)–(11) consists in approximating them with a sequence of regularized systems, the solutions of which, together with the and generated by them, satisfy the integral identity defining the weak solution. The proposed method of regularization of the original field u provides the necessary properties of functions , , and for the limit passage to u, z, and , respectively. This takes into account the inhomogeneity of the condition on u at the boundary of the multi-connected domain and the belonging of u to the Sobolev space.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.Z.; methodology, V.O.; validation, V.Z., V.O. and A.Z.; formal analysis, A.Z.; investigation, V.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (project 23-71-10026).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hartman, P. Ordinary Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; Birkhauser: Boston, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Zvyagin, V.G.; Vorotnikov, D.A. Topological Approximation Methods for Evolutionary Problems of Nonlinear Hydrodynamics; Walter de Gruyter & Co.: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zvyagin, V.G.; Orlov, V.P. On the solvability of the initial boundary value problem for one model of viscoelasticity with fractional derivatives. Sib. Math. J. 2018, 59, 1073–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyagin, V.G.; Dmitrienko, V.T. On weak solutions of the initial boundary value problem for a regularized model of a viscoelastic fluid. Differ. Equ. 2002, 38, 1731–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyagin, V.G.; Orlov, V.P. On the weak solvability of the viscoelasticity problem with memory. Differ. Equ. 2017, 53, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyagin, V.G.; Orlov, V.P. The weak solvability of an inhomogeneous dynamic problem for a viscoelastic continuum with memory. Funct. Anal. Its Appl. 2023, 57, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyagin, V.G.; Orlov, V.P. On weak solvability of a flow problem for viscoelastic fluid with memory. Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 2023, 63, 2090–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, V.P. A non-homogeneous regularized problem of dynamics of viscoelastic continuous medium. Russ. Math. 2012, 56, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobkov, M.V.; Pileckas, K.; Pukhnachov, V.V.; Russo, R. The flux problem for the Navier-Stokes equations. Russ. Math. Surv. 2014, 69, 1065–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyagin, V.G.; Orlov, V.P. The problem of the flow of one type of non-Newtonian fluid through the boundary of a multi-connected domain. Dokl. Math. 2023, 107, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krein, S.G. Functional Analysis; Wolters-Noordhoff Publishing: Groningen, The Netherlands, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Temam, R. Navier-Stokes Equations. Theory and Numerical Analysis; North-Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Nikol’skii, S.M. Approximation of Functions of Several Variables and Imbedding Theorems; Springer: Berlin, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, W. Principles of Mathematical Analysis, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ladyzhenskaya, O.A. The Mathematical Theory of Viscous Incompressible Flow; Gordon and Breach Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- DiPerna, R.J.; Lions, P.L. Ordinary differential equations, transport theory and Sobolev spaces. Invent. Math. 1989, 98, 511–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, L. Transport equation and Cauchy problem for BV vector fields. Invent. Math. 2004, 158, 227–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, G.; de Lellis, C. Estimates and regularity results for the diPerna-Lions flow. J. Fur Die Reine Angew. Math. 2008, 616, 15–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).