Abstract

We consider the problem of extending a function defined on a subset P of an arbitrary set X to X strictly monotonically with respect to a preorder ≽ defined on X , without imposing continuity constraints. We show that whenever ≽ has a utility representation, is extendable if and only if it is gap-safe increasing. This property means that whenever xx, the infimum of on the upper contour of x exceeds the supremum of on the lower contour of x, where x, x and is X completed with two absolute ≽-extrema and, moreover, is weakly increasing. The completion of X makes the condition sufficient. The proposed method of extension is flexible in the sense that for any bounded utility representation u of ≽, it provides an extension of that coincides with u on a region of X that includes the set of P-neutral elements of X . An analysis of related topological theorems shows that the results obtained are not their consequences. The necessary and sufficient condition of extendability and the form of the extension are simplified when P is a Pareto set.

Keywords:

extension of utility functions; monotonicity; utility representation of a preorder; lifting theorems MSC:

91B16; 06A06

1. Introduction

We consider the following problem. For an arbitrary nonempty preordered set let be a bounded utility representation of ≽. Suppose that is a new (updated, renewed) utility function on an arbitrary subset Under what conditions and how can be extended to X so that the resulting function f represents ≽ on X and coincides with u on the “ P-neutral” subset ?

In this setting, f can be considered as an update of utility function u that adjusts it to If all elements of X are feasible, then the conditions for the extendability of to X are actually those of the consistency of

In this paper, we present a simple necessary and sufficient condition for the extendability of and, in the case where this condition is satisfied, we provide the extension (12) of coinciding with u on a region of X that includes Moreover, we consider the case where the structure of subset P minimally restricts functions representing ≽ on P . This is the case of Pareto sets P (in which for no ); for such sets, the proposed extension takes a simpler form.

Starting with the classical results of Eilenberg [1], Nachbin [2,3], and Debreu [4,5,6,7], much of the work related to utility functions has been conducted under the continuity assumption [8,9]. Sometimes, this assumption was made just “for purposes of mathematical reasoning” [10]. However, this requirement is not always necessary. Moreover, there are threshold effects [11,12] such as a shift from quantity to quality or disaster avoidance behavior that require utility jumps. In other situations, the feasible set of possible outcomes is discrete, which may eliminate the continuity constraints. Thus, utility functions that may not be continuous everywhere are useful or even necessary to model some real-world problems [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. For a discussion of various versions of the continuity postulate in utility theory, we refer to [20].

Thus, in this paper, we study the problem of extending utility functions defined on arbitrary subsets of an arbitrary set X equipped with a preorder ≽ but not endowed with a topological structure, since we do not impose continuity requirements. On the other hand, some kind of continuity of an associated inverse mapping follows from the necessary and sufficient condition of extendability we establish.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 contains standard definitions, introduces and discusses the concept of a gap-safe increasing function, presents preliminary results, and recalls basic facts on the extension of preorders and corresponding utilities.

Section 3 contains the main results. Its subsections present Theorem 1 on the extension of a function defined on an arbitrary subset P of an arbitrary preordered set (where ≽ has a utility representation) to the whole set (Section 3.1), alternative representations of the extension (Section 3.2), and the application of Theorem 1 to the special case of Pareto sets (Section 3.3).

Theorem 1 solves the extendability problem in the strictly increasing version. Another feature of the problem under study is that it does not involve continuity constraints, which, as mentioned above, matches certain classes of applications. This enables us to obtain a simple and easily interpretable necessary and sufficient extendability condition, that is, the property of gap-safe increase. Under this condition, Theorem 1 introduces a class of extensions based on arbitrary bounded utility representations of ≽. Furthermore, as follows from Proposition 5 and Corollary 1, the resulting extension coincides with the chosen utility representation of ≽ on a region of X that contains the set . This provides a solution to the problem of constructing a utility extension consistent (i.e., coinciding on N ) with an arbitrary bounded representation of ≽. The latter problem can be treated as the problem of updating utility functions. Propositions 3–5 provide additional representations of the proposed utility extension that highlight its properties. They may give rise to alternative formulations of Theorem 1. In the case where P is such that for no (a Pareto set), the necessary and sufficient extendability condition simplifies. Namely, by Lemma 2, is gap-safe increasing if and only if it is upper-bounded on lower P-contours, lower-bounded on upper P-contours, and preserves the ≽-equivalence. The form of the proposed utility extension also simplifies in this case (Corollary 2).

In Section 4, we discuss the connection of the above results to related work. Most of the work on the extension of functions that represent preorders was performed in the topological framework under continuity assumptions. In the case of strictly increasing functions, this leads to rather complex extendability conditions (see [21,22,23,24]). Technically, solutions to the extension problems without continuity requirements can be obtained from the corresponding general topological results by applying them to the discrete topology. However, the only topological result [23] we know that corresponds to the problem under consideration contains an inaccuracy that makes it impossible to derive the gap-safe increase extendability condition from it. This is demonstrated using Example 2. Furthermore, the results of this kind involve extension algorithms that differ from the flexible approach we use, and they do not solve the problem of updating an existing bounded utility function u using as a correcting function. In Section 4, we also briefly touch on the application of the results obtained.

Section 5 contains all the proofs. In Appendix A, we list the relevant properties and classes of binary relations.

2. Basic Definitions and Methods

2.1. The Problem and Standard Definitions

Throughout the paper, is (To denote a preorder, symbols ≽[25] or ≿[6] are used. Variables for the elements of X are printed in bold (as is common for vectors in ) to distinguish them from the variables for real numbers.) a preordered set , where X is an arbitrary nonempty set, and ≽ is a preorder (i.e., a transitive and reflexive binary relation) defined on We first formulate the problem under consideration and then provide the necessary definitions; the basic properties and classes of binary relations are defined in Appendix A.

Suppose that ≽ has a utility representation; let be a bounded utility representation of ≽. Consider any subset and any real-valued function defined on P . The problem studied in this paper is (1) to find conditions under which can be extended to X yielding a function strictly increasing with respect to ≽ and coinciding with u on the subset and (2) to propose such an extension.

The definitions of the relevant terms are as follows.

Given a preorder ≽ on the asymmetric ≻ and symmetric ≈ parts of ≽ are the relations and not ] and and ], respectively, where ≡ is “identity by definition”. Relation ≻ is transitive and irreflexive (i.e., it is a strict partial order ), whereas ≈ is transitive, reflexive, and symmetric (i.e., it is an equivalence relation ).

The converse relations corresponding to ≽ and ≻ are and respectively. For any is the restriction of ≽ to P .

is a maximal ( minimal ) element of iff (resp., ) for no

Definition 1.

A function where is said to be weakly increasing with respect to the preorder ≽ defined on X (or, briefly, weakly increasing ) if for all implies (In the terminology of [26], functions with this property are called order-preserving, or isotone (with ≽ being a partial order). Note that in other papers (e.g., [27,28]), strictly increasing functions are called order-preserving.)

If, in addition, for all such that then is called strictly increasing with respect to ≽, or a utility representation [6] of .

Utility functions strictly increasing with respect to ≽ can express the attitude, consistent with the preference preorder ≽, of a decision maker towards the elements of P . Utility representations of preorders and partial orders have been studied since [3,25,29,30].

It follows from Definition 1 that for any weakly increasing function ,

Using (1), we obtain the following simple lemma.

Lemma 1.

A function where is strictly increasing with respect to a preorder ≽ defined on X if and only if for all

where ≈ and ≻ are the symmetric and asymmetric parts of respectively.

Indeed, (2) follows from Definition 1 using (1). Conversely, if (2) holds, then since implies with the desired conclusion in either case, while the second condition is immediate.

Definition 2.

A real-valued function defined on is strictly monotonically (we mean increasing) extendable to if there exists a function such that:

the restriction of f to P coincides with ;

f is strictly increasing on X with respect to ≽.

In this case, f is said to be a strictly increasing extension of to .

In economics and decision-making, alternatives are often identified with k-dimensional vectors of criteria values [31] or goods [10]. In such cases, Thus, an important special case of the extendability problem is the problem of extending to functions defined on and strictly increasing with respect to the Pareto preorder on . The Pareto preorder ≽ [32] is defined as follows: for any and that belong to for all .

2.2. Extensions of Preorders and Corresponding Utilities

Extensions of preorders and partial orders and their numerical representations have been studied since Szpilrajn’s theorem [33], according to which, every partial order can be extended to a linear order.

Another basic result is that a preorder ≽ has a utility representation whenever there exists a countable dense ( is R-dense [25] in where R is a binary relation on X , iff ⇒ [ or or [ and for some ]]) (with respect to the induced partial order) subset in the factor set where ≈ is the symmetric part of ≽ [7,25,34]. This is not a necessary condition; however, for the subclass of weak orders (i.e., connected preorders), it is necessary.

Among the extensions of the Pareto preorder on are all lexicographic linear orders [6,25] on . When , these extensions lack utility representations [7], while a utility representation of the Pareto preorder is any function strictly increasing in all coordinates.

Any utility representation of a preorder ≽ induces a weak order that extends ≽. In turn, this weak order determines a utility representation of ≽ up to an arbitrary strictly increasing transformation; for certain related results, see [8,9,25,35,36,37]. As was seen on the example of the Pareto preorder, not all weak orders extending ≽ correspond to utility representations of ≽. However, this is true when X is a vector space and the weak order has the Archimedean property, which ensures [25] the existence of a countable dense (with respect to this weak order) subset of X .

2.3. Utility Bounds on Upper and Lower Contours

Theorem 1 below provides a necessary and sufficient condition for the strictly increasing extendability (with respect to a preorder ≽ having a utility representation) of a function defined on any subset P of Moreover, this theorem presents such an extension based on any bounded utility representation of ≽. As follows from Proposition 5 and Corollary 1, this extension coincides with on the region that contains the P-neutral subset

We now present the notation used in Theorem 1 and simple facts related to it.

Following [7], consider the extended real line :

with the ordinary > relation supplemented by and for all . Since the extended > relation is a strict linear order, it determines unique smallest () and largest () elements in any nonempty finite .

Functions and are considered as maps from to defined for as follows: and . This preserves inclusion monotonicity , i.e., the property that does not decrease and does not increase with the expansion of the set Q (cf. [38], (Section 4)). Throughout, we assume and whenever while indeterminacies like never occur in our expressions.

Remark 1.

If and Y is bounded, then defining and on with the preservation of inclusion monotonicity allows one to set and where a and b are any strict lower and upper bounds of respectively. This is applicable to below whenever the range of is bounded.

Definition 3.

For any and the lower P-contour and the upper P-contour of are and respectively.

For any , where , define two functions from X to :

By definition, the “lower supremum” and “upper infimum” functions can take values and along with real values.

It follows from the transitivity of ≽ and the inclusion monotonicity of the sup and inf functions that for any (not necessarily increasing) functions and are weakly increasing with respect to ≽:

Consequently,

Furthermore, since implies it holds that

We use the following characterizations of the class of weakly increasing functions in terms of and

Proposition 1.

For any and the following statements are equivalent:

is weakly increasing;

The proofs are given in Section 5.

Remark 2.

In view of Equation (7), the inequality in items to of Proposition 1 can be replaced by an equality.

2.4. Gap-Safe Increasing Functions

We now consider the class of gap-safe increasing functions which is no wider but can be narrower for some X and P than the class of strictly increasing functions (see Proposition 2 and Example 1 below). It is shown that this is precisely the class of functions that admits a strictly increasing extension to .

Let us extend X in the same manner as is extended by (3):

where and are two distinct elements that do not belong to Preorder is extended to as follows:

where and are pairs of elements of

Functions , are defined in the same way as in (4).

Definition 4.

A function where is gap-safe increasing with respect to a preorder ≽ defined on X (or, briefly, gap-safe increasing ) if is weakly increasing and for any implies .

The term “gap-safe increasing” refers to the property of a function to orderly separate its values when the corresponding sets of arguments are orderly separated () in X ; see also Remark 3. In [39], the term “separably increasing function” was used, clashing with topological separability, which means the existence of a countable dense subset.

Proposition 2.

If defined on is gap-safe increasing, then:

is strictly increasing;

is (an equivalent formulation is: there is no such that or ) upper-bounded on the lower P-contour and lower-bounded on the upper P-contour of for every

It should be noted that there are functions that are strictly increasing, upper-bounded on all lower P-contours and lower-bounded on all upper P-contours but are not gap-safe increasing.

Example 1.

Consider

where ≽ is induced by the ≥ relation on Function satisfies (a) and (b) of Proposition 2, but it is not gap-safe increasing. Indeed, but

Remark 3.

The gap-safe increase as a property of a function can be interpreted as follows. If is weakly increasing, then implies for any as ⇒ in Proposition For the class of strictly increasing functions the conclusion cannot be strengthened to as Example 1 shows. This stronger conclusion holds for gap-safe increasing functions, i.e., is incompatible with for them. In other words, the absence of a gap in the values of between P-contours “ or higher” (with infimum given by and “ or lower” (with supremum of implies Hence, the gap-safe increase as a property of a function can be viewed as a kind of continuity of the inverse mapping: there is no gap in its values whenever there is no gap in the argument

3. Results

3.1. Extending Gap-Safe Increasing Functions

Let defined on any be gap-safe increasing. Theorem 1 below states that this is a necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of strictly increasing extensions of to provided that ≽ enables a utility representation. Furthermore, for any such bounded representation , the theorem provides an extension of a gap-safe increasing function that combines it with .

In precise terms, for any such that let be a utility representation of ≽ (i.e., a function strictly increasing with respect to ≽) satisfying

For any (unbounded) utility representation of , such a function can be obtained, for example, using transformation

In particular, consider the functions that satisfy

They are normalized versions of the above utilities :

For any real and and any utility representations of we define

For an arbitrary gap-safe increasing function given by (11) is well defined as the two terms in the right-hand side are finite. This follows from item of Proposition 2. For preordered sets that have minimal or maximal elements (see Example 2 in Section 4, where has a maximal element), this is ensured by introducing the augmented sets in the definition of a gap-safe increasing function. Indeed, since and for all Definition 4 provides and hence and i.e., is upper-bounded on all lower P-contours and lower-bounded on all upper P-contours, ensuring the correctness of definition (11). If has neither minimal nor maximal elements (like the Pareto preorder on ), then the replacement of with X in Definition 4 does not alter the class of gap-safe increasing functions.

We now formulate the main result.

Theorem 1.

Suppose that a preorder ≽ defined on X has a utility representation and is a real-valued function defined on some . Then, is strictly monotonically extendable to if and only if is gap-safe increasing.

Under these conditions, function f defined by (11), where is any utility representation of ≽ that satisfies (9) and is a strictly increasing extension of to .

3.2. Extension of Utility: Additional Representations

The class of extensions introduced by Theorem 1 allows alternative representations that clarify its properties. They are given by Propositions 3–5.

Proposition 3.

If is a utility representation of ≽ satisfying (8) and where is gap-safe increasing, then

is a strictly increasing extension of to and coincides with function (11), where is related to by (10).

The order of proofs in Section 5 is as follows. The verification of the second statement of Proposition 3 is straightforward and is omitted. This statement is used to prove Proposition 5, which implies Proposition 4, and they both are used in the proof of Theorem 1, which in turn implies the first statement of Proposition 3.

Clearly, these regions are pairwise disjoint, and .

Proposition 4.

If is a utility representation of ≽ satisfying (8) and where is gap-safe increasing, then function f defined by (12) can be represented as follows:

Proposition 4 highlights the role of in (12). Function f reduces to on P and to on N whose elements are ≽-incomparable with those of P . Moreover, on the part of L where and on the part of U where On the complement parts of L and U , and respectively. On (12) is not simplified. This fact and the ambiguity on L and U prompt us to make another decomposition of

Consider four regions that depend on and :

It is easily seen that whereas the -regions are not disjoint. This decomposition allows us to express without min and max.

Proposition 5.

For a gap-safe increasing f defined by (11) can be represented as follows, where and are representations of ≽ related by (10):

Thus, on is a convex combination of and with coefficients and respectively. The regions and intersect on some parts of the border sets , , and . Accordingly, the expressions of f given by Proposition 5 are concordant on these intersections.

Corollary 1.

In the notation and assumptions of Proposition 5,

For any implies In particular, if for some then and

3.3. Extension of Functions Defined on Pareto Sets

Consider the case where P is a Pareto set. In decision making, such a set comprises elements of X that are mutually undominated.

Definition 5.

A subsetis called a Pareto set inif there are nosuch thatwhere ≻ is the asymmetric part of ≽.

For functions defined on Pareto sets P, the necessary and sufficient condition of the extendability to given by Theorem 1 reduces to the boundedness on all P-contours (which appeared in Proposition 2) supplemented by condition (1): .

Lemma 2.

A function defined on a Pareto set is gap-safe increasing with respect to a preorder ≽ defined on X if and only if is upper-bounded on all lower P-contours, lower-bounded on all upper P-contours, and satisfies where ≈ is the symmetric part of ≽.

By the transitivity of ≽, for any Pareto set the sets and have a simple structure described in the following lemma.

Lemma 3.

Under the conditions of Lemma 2 where and A are defined by (15) and (13), respectively.

Lemmas 2 and 3, Propositions 4 and 5, and Corollary 1 yield the following special case of Theorem 1 for Pareto sets.

Corollary 2.

Suppose that a preorder ≽ on X has a utility representation satisfying (8) and is a Pareto set. Then, a function is strictly monotonically extendable to if and only if it is upper-bounded on all lower P-contours, lower-bounded on all upper P-contours, and satisfies where ≈ is the symmetric part of ≽.

Under these conditions, the function such that

is a strictly increasing extension of to coinciding with (12).

| wheneverand | |

| is defined by (14) or (16), | when |

It follows from Corollary 2 that for a Pareto set P , functions and influence f in a similar but different way: f reduces to on to on , and is determined by the sum or on

4. Discussion and Connections to Related Work

Problems of extending real-valued functions while preserving monotonicity (sometimes called lifting problems [28]) have been considered primarily in topology. Therefore, continuity was usually a property to be preserved. This strand of literature started with the following theorem of general topology.

- Urysohn’s extension theorem [40]. A topological space is normal (a topological space is called normal if for any two disjoint closed subsets of X there are two disjoint open subsets each covering one of the closed subsets) if and only if every continuous real-valued function whose domain is a closed subset can be extended to a function continuous on

For metric spaces, a counterpart to this theorem was proved by Tietze [41].

Nachbin [3] obtained extension theorems for functions defined on preordered spaces. In his terminology, a topological space equipped with a preorder ≽ is normally preordered if for any two disjoint closed sets being decreasing (i.e., with every containing all such that ) and increasing (with every containing all such that ), there exist disjoint open sets and decreasing and increasing, respectively, such that and The space is normally ordered if, in addition, its preorder ≽ is antisymmetric (i.e., it is a partial order).

- Nachbin’s lifting theorem [3] for compact sets in ordered spaces. In any normally ordered space whose partial order ≽ is a closed subset of every continuous weakly increasing real-valued function defined on any compact set can be extended to X in such a way as to remain continuous and weakly increasing.

An analogous theorem for more general normally preordered spaces is ([42], (Theorem 3.4)). Sufficient conditions for to be normally preordered are (a) compactness of X and ≽ belonging to the class of closed partial orders ([3], (Theorem 4 in Chapter 1)) (this result was strengthened in [42]) and (b) connectedness and closedness of ≽ [43].

Additional utility extension theorems in which P is a compact set, is continuous, and f is required to be continuous and weakly increasing as well as are discussed in [9].

The extendability of continuous functions defined on noncompact sets P requires a stronger condition. It can be formulated as follows:

For a function where let the lower -contour and the upper -contour of denote the sets and respectively. Let us say that is inversely closure-increasing if for any such that there exist two disjoint closed subsets of X : a decreasing set containing and an increasing set containing

- Nachbin’s lifting theorem [3] for closed sets in preordered spaces. In any normally preordered space a continuous weakly increasing bounded function defined on a closed subset can be extended to X in such a way as to remain continuous, weakly increasing, and bounded if and only if is inversely closure-increasing.

For several other results regarding the extension of weakly increasing functions defined on noncompact sets we refer to [21,42,44].

Theorems on the extension of strictly increasing functions were obtained in [21,22,23,24]. Herden’s Theorem 3.2 [21] contains a compound condition consisting of several arithmetic and set-theoretic parts, which is not easy to grasp. To formulate a more transparent result ([23], (Theorem 2.1)) let us introduce the following notation. Using Definition 3, for any , define the decreasing cover of and the increasing cover of . In these terms, Z is decreasing (increasing) whenever (resp., . A preorder is said to be continuous [45] if for every open both and are open. A preorder ≽ is separable (on connections between versions of preorders’ separability and denseness, see [37]) if there exists a countable such that For , denote by and the collections of open decreasing and open increasing sets containing , respectively.

- Hüsseinov’s extension theorem [23] for strictly increasing functions. In any normally preordered space with a separable and continuous preorder a continuous strictly increasing function defined on a nonempty closed subset can be extended to X in such a way as to remain continuous and strictly increasing if and only if is such that for any implies , and for any wherewith the convention that if for some , and if for some

This theorem is a topological counterpart to the first part of our Theorem 1. Consider the discrete topology in which every subset of X is open. Then, the space is normally preordered, and the preorder ≽ is continuous, as well as any function . The separability of ≽ in Hüsseinov’s theorem ensures its representability by utility, which is explicitly assumed in Theorem 1.

Condition reduces to where and modify and by taking values or instead of or when or respectively. It is easily seen that conditions and are equivalent (cf. Remark 1), therefore, by of Proposition 1, for all reduces in the discrete topology to the weak increase property of .

The last condition, proposed in [39] and forming the essence of gap-safe increase, is required for all in the above theorem and for all in Theorem 1. This difference is significant, as the following example illustrates.

Example 2.

for all .

Then, has no strictly increasing extension to and is not gap-safe increasing, since , but However, for all therefore, the above theorem claims that is strictly monotonically extendable to .

The reason for the above claim is that ([23], (Theorem 2.1)) was actually proved for a bounded function ; however, the boundedness condition was removed by a remark erroneously claiming that this condition was not essential. Note that the lifting theorems in [28] apply to either bounded functions or compact sets The method of extension proposed in the present paper differs from the classical approach, which is systematically applied to continuous functions.

In [22], Hüsseinov shows that condition for all is equivalent to the necessary and sufficient extendability condition for a weakly increasing bounded function defined on a closed subset of a preordered space, i.e., to the aforementioned Nachbin property of being inversely closure-increasing.

The problem of extending utility functions without continuity constraints was considered in [39] with the focus on the functions representing Pareto partial orders on Euclidean spaces. Partial orders are antisymmetric preorders; therefore, preorders are more flexible, allowing symmetry () on a pair of distinct elements, while partial orders only allow “negative” () symmetry. Symmetry is an adequate model for the equivalence between objects (which suggests the same value of the utility function), while “negative” symmetry can model the absence of information, which is generally compatible with unequal utility values.

Returning to the meaning of Theorem 1, observe that together with Proposition 4, it implies that for any the utility on the set can be defined using any bounded representation of ≽. If and are fixed, then by Proposition 5 and Corollary 1, can be set on the region (see (15)), which contains N and can be significantly wider. Such a definition cannot violate the extendability of to . This observation demonstrates that the results obtained solve the problem of updating utility functions. In this problem, given and a bounded utility function representing we consider as a function that contains corrective information. The task is to find a condition under which is extendable to in such a way that the resulting updated utility function f coincides with on N (or on ) and to construct such an extension.

Versions of Theorem 1 and Corollary 2 were used in [46,47] to construct implicit representations of scoring procedures for preference aggregation and the evaluation of the centrality of network nodes. More specifically, theorems of this type allow us to move from axioms that determine a positive impact of the comparative results of objects and “neighbors’ power” on their functional scores to the conclusion that the scores are a solution to a system of equations determined by a strictly increasing function.

5. Proofs

Proof of Proposition 1.

. Let hold. For any if or then or respectively, with in both cases. Otherwise, and imply and by the transitivity of ≽. Hence, by Therefore, i.e.,

. Let hold. Then, for any such that , using (5), we obtain

. As ≽ is reflexive, follows from .

. [For all ] ⇔ [for all ] ⇔ [for all ].

. [ and the last inequality of (7)] ⇒

as . □

Proof of Proposition 2.

Let be gap-safe increasing.

Assume that is not strictly increasing. Since is weakly increasing, there are such that and . Then, by (7), holds, i.e., is not gap-safe increasing. Therefore, the assumption is wrong.

Let be the lower P-contour of some . By definition, and Since is gap-safe increasing, . Since , is upper-bounded on . Similarly, is lower-bounded on all upper P-contours. □

Next, we prove Proposition 5; then, it is used to prove Proposition 4 and Theorem 1.

Proof of Proposition 5.

Let Since we have

hence

Therefore, (12) reduces to .

Let Inequalities and imply , hence (11) reduces to .

Let Inequalities and imply , hence (11) reduces to .

Finally, let i.e., and Substituting and into (12) yields □

Proof of Proposition 4.

Finally, if then and , whence and , and Proposition 5 provides . □

Proof of Theorem 1.

Suppose that is strictly monotonically extendable to . Then, is strictly increasing with respect to ≽. Assume that is not gap-safe increasing. This implies that there are such that and If then using this inequality, the definition of and and the strict monotonicity of we obtain whence , and as f is not strictly increasing. Therefore, If then implies and By the assumption, hence ; thus, and Since , cannot be assigned a value compatible with the strict monotonicity of f , whence is not strictly monotonically extendable to , there is a contradiction. The case of is considered similarly. It is proved that is gap-safe increasing whenever is strictly monotonically extendable to .

Now, let be gap-safe increasing. By Proposition 4, the restriction of f to P coincides with .

It remains to prove that f is strictly increasing on X . This can be shown directly by analyzing expression (11). Here, we give a proof that does not require the analysis of special cases with and .

We use Lemma 1. First, consider any such that and show that By (6), and Furthermore, and are strictly increasing with respect to ≽ by definition; hence, and Therefore, by (16), holds.

Now, suppose that and . Then, by (5) and the strict monotonicity of and , we have

Let and belong to the same region: or . Inequalities (17) yield

hence, by (16), f is strictly increasing on each of these regions.

This implies that is possible only if and , hence only if . The last equality is impossible, since is gap-safe increasing by assumption. Therefore, , and f is strictly increasing on .

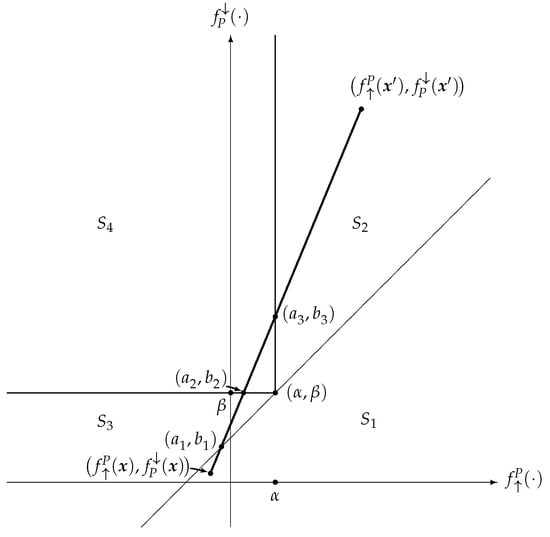

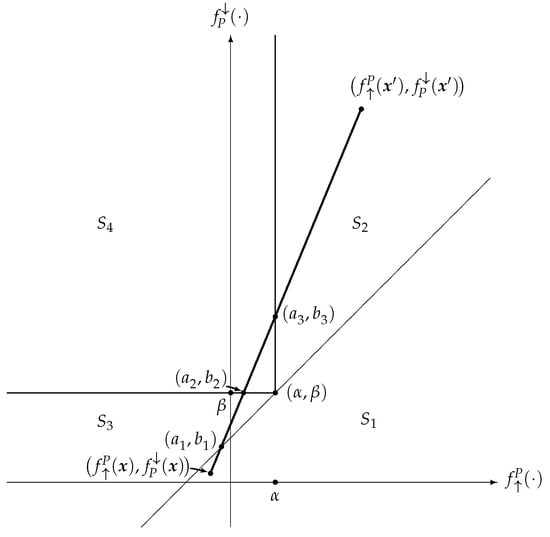

Now, let and belong to different regions and . Consider the points that represent and in the three-dimensional space with axes corresponding to , , and . Let us connect these points, and , by a line segment. The projections of this segment and the borders of the regions and onto the plane are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An example of line segment in the space with axes , , and projected onto the plane .

Suppose that , , are the consecutive points where the line segment crosses the planes and separating the S -regions on the way from to Then, by the linearity of the segment, it holds that

with strict inequalities in (18) or in (19), or in both (since otherwise and belong to the same S-region).

Consider f represented by (16) as a function of , and . Then, using the fact that is nondecreasing in all variables on each region, strictly increasing in v on and , and strictly increasing in a and b on , and the fact that each point () belongs to both regions on the border of which it lies, we obtain

Thus, , and f is strictly increasing. Theorem 1 is proved. □

Proof of Corollary 1.

hence, and which satisfies the conditions of

implies whence follows from (16).

If and then since is gap-safe increasing and thus weakly increasing, Equation (6), Remark 2, and of Proposition 1 imply hence, and □

Proof of Lemma 2.

If is gap-safe increasing, then the conditions presented in Lemma 2 are satisfied due to Proposition 2 and Lemma 1.

Conversely, suppose that these conditions hold. By the definition of a Pareto set, for any reduces to and the condition implies that is weakly increasing.

Assume that is not gap-safe increasing. Then, there exist such that and . This is possible only if (a) , or (b) , or (c) there are such that However, in (a), and (since is incompatible with and is incompatible with ); hence, is not upper-bounded on a lower P-contour. Similarly, in (b), and (since is incompatible with and is incompatible with ); hence, is not lower-bounded on an upper P-contour. In (c), by the “mixed” strict transitivity of preorders ( and ), we have hence, P is not a Pareto set. In all cases, we obtain a contradiction; therefore, is gap-safe increasing. □

Proof of Lemma 3.

Let Then, . Indeed, otherwise, either or , and since is upper-bounded on all lower P-contours and lower-bounded on all upper P-contours, , which contradicts the assumption. Therefore,

Let Then, there exist such that

and by the transitivity of Since P is a Pareto set, By the transitivity of the latter is incompatible with in (20); consequently, for some

Let for some Then, by the last statement of Corollary 1, This completes the proof. □

6. Conclusions

The paper presents a strict-extendability condition and, if this condition is met, a class of extensions for a function defined on an arbitrary subset P of an arbitrary set X equipped with a preorder ≽. For any bounded utility representation of ≽, the proposed class contains an extension f of that updates in the sense that f coincides with on a region of X that includes the set of P-neutral (incomparable in terms of ≽ with the members of P) elements of X . The class of extensions under study is presented in several forms, which clarify its properties. If all elements of X are feasible, then the conditions for the extendability of to X are actually those of the consistency of The necessary and sufficient extendability condition, i.e., the gap-safe increase property of , and the proposed extension simplify when P is a Pareto set. The results obtained are not consequences of topological theorems found in the literature. Versions of these results have been used to show that certain indirect scoring procedures designed for preference aggregation or measuring centrality in networks produce scores that are solutions to systems of equations of a special form.

The formulation of the gap-safe increase involves augmenting X with two absolute ≽-extrema, which makes the condition sufficient. The structure of this condition is similar to that of the inverse closure-increase, which is equivalent to the extendability of a continuous weakly increasing function defined on a closed subset (we refer to [8] for a related discussion). Moreover, as mentioned in Section 4, the latter “inverse” condition has an equivalent “direct” counterpart. Relationships of this kind deserve further study.

Among other problems, we mention: (1) exploring relationships between various extensions proposed earlier for continuous functions and the extension proposed in this paper; (2) characterizing the entire class of extensions of to (and, for instance, to )); (3) exploring the extension problem with as the range of f replaced by certain other posets.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union (ERC, GENERALIZATION, 101039692). Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union or the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Fuad Aleskerov, Andrey Brevern, Ron Holzman, Pavel Shvartsman, and Elena Yanovskaya for helpful discussions, Mikhail Goubko for his invaluable assistance, and three anonymous referees for their comments that helped improve the presentation of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Binary Relations

A binary relation R on a set X is a set of ordered pairs of elements of X (); is abbreviated as .

A binary relation is

- Reflexive if holds for all ;

- Irreflexive if holds for no ;

- Transitive if and imply for all ;

- Symmetric if implies for all ;

- Antisymmetric if and imply for all ;

- Connected if or holds for all such that

A binary relation is a/an:

- Preorder (or quasi-order) if it is transitive and reflexive;

- Partial order if it is transitive, reflexive, and antisymmetric;

- Strict partial order if it is transitive and irreflexive;

- Weak order if it is a connected preorder;

- Linear (or total) order if it is an antisymmetric weak order (or, equivalently, a connected partial order);

- Strict linear order if it is a connected strict partial order;

- Equivalence relation if it is transitive, reflexive, and symmetric.

A relation Rextends a relation if

References

- Eilenberg, S. Ordered topological spaces. Am. J. Math. 1941, 63, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachbin, L. A theorem of the Hahn-Banach type for linear transformations. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1950, 68, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachbin, L. Topology and Order; Van Nostrand: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. Translation of Topologia e Ordem; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1950. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Debreu, G. Representation of a preference ordering by a numerical function. In Decision Processes; Thrall, R.M., Coombs, C.H., Davis, R.L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1954; pp. 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Debreu, G. Topological Methods in Cardinal Utility Theory; Discussion Papers 299; Cowles Foundation: New Haven, CT, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Debreu, G. Theory of Value: An Axiomatic Analysis of Economic Equilibrium; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Debreu, G. Continuity properties of Paretian utility. Int. Econ. Rev. 1964, 5, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, D.S.; Mehta, G.B. Representations of Preferences Orderings; Vol. 422, Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Evren, Ö.; Hüsseinov, F. Extension of monotonic functions and representation of preferences. Math. Oper. Res. 2021, 46, 1430–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.D. The nature of indifference curves. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1934, 1, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, J.; Jack, H.; Riley, J.G. The Analytics of Uncertainty and Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kritzman, M. What practitioners need to know... about time diversification (corrected). Financ. Anal. J. 1994, 50, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, D.; Sutherland, W.R. Analysis of a one good model of economic development. In Mathematics of the Decision Sciences, Part 2; Dantzig, G.B., Veinott, A.F., Eds.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1968; pp. 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, R.T. Utility functions with jump discontinuities: Some evidence and implications from peasant agriculture. Econ. Inq. 1974, 12, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hande, P.; Zhang, S.; Chiang, M. Distributed rate allocation for inelastic flows. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2007, 15, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diecidue, E.; Van De Ven, J. Aspiration level, probability of success and failure, and expected utility. Int. Econ. Rev. 2008, 49, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliani, L. Paying for performance and motivation crowding out. Econ. Lett. 2009, 103, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J.; Sprenger, C. Certain and uncertain utility: The Allais paradox and five decision theory phenomena. Levine’s Working Paper Archive . 2010; Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, B.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z.Q. Utility maximization under trading constraints with discontinuous utility. SIAM J. Financ. Math. 2019, 10, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanik, M.; Khan, M.A. The continuity postulate in economic theory: A deconstruction and an integration. J. Math. Econ. 2022, 101, 102704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herden, G. Some lifting theorems for continuous utility functions. Math. Soc. Sci. 1989, 18, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüsseinov, F. Monotonic Extension; Department of Economics Discussion Paper 10–04; Bilkent University: Ankara, Türkiye, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hüsseinov, F. Extension of Strictly Monotonic Functions in Order-Separable Spaces; Working Paper 3260586; ADA University: Baku, Azerbaijan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hüsseinov, F. Extension of strictly monotonic functions and utility functions on order-separable spaces. Linear Nonlinear Anal. 2021, 7, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fishburn, P.C. Utility Theory for Decision Making; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Birkhoff, G. Lattice Theory; AMS Colloquium Publications; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1940; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Bosi, G. Continuous order-preserving functions for all kind of preorders. Order 2023, 40, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, G.; Zuanon, M. Lifting theorems for continuous order-preserving functions and continuous multi-utility. Axioms 2023, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumann, R.J. Utility theory without the completeness axiom. Econometrica 1962, 30, 445–462, A Correction Econometrica 1964, 32, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, B. Utility functions for partially ordered topological spaces. Econometrica 1970, 38, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, J.J. Multi-Criteria Decision Making; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Debreu, G. Stephen Smale and the economic theory of general equilibrium. In From Topology to Computation: Proceedings of the Smalefest; Hirsch, M.W., Marsden, J.E., Shub, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Szpilrajn, E. Sur l’extension de l’ordre partiel. Fundam. Math. 1930, 16, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.K. Revealed preference theory. Econometrica 1966, 34, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkeliūnas, A. On strictly increasing numerical transformations and the Pareto condition. Liet. Mat. Rink./Litov. Mat. Sb. 1986, 26, 729–737. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Morkeliūnas, A. On the existence of a continuous superutility function. Liet. Mat. Rink./Litov. Mat. Sb. 1986, 26, 292–297. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Herden, G. On the existence of utility functions. Math. Soc. Sci. 1989, 17, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanino, T. On supremum of a set in a multi-dimensional space. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1988, 130, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotarev, P. On the extension of utility functions. In Constructing and Applying Objective Functions; Tangian, A.S., Gruber, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical System; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2002; Volume 510, pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Urysohn, P. Über die Mächtigkeit der zusammenhängenden Mengen. Math. Ann. 1925, 94, 262–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietze, H. Über Funktionen, die auf einer abgeschlossenen Menge stetig sind. J. Reine Angew. Math. 1915, 145, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minguzzi, E. Normally preordered spaces and utilities. Order 2013, 30, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, G. Topological ordered spaces and utility functions. Int. Econ. Rev. 1977, 18, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herden, G. On a lifting theorem of Nachbin. Math. Soc. Sci. 1990, 19, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartan, D. Bicontinuous preordered topological spaces. Pac. J. Math. 1971, 38, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotarev, P.Y.; Shamis, E. Characterizations of scoring methods for preference aggregation. Ann. Oper. Res. 1998, 80, 299–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotarev, P. Selection of centrality measures using Self-consistency and Bridge axioms. J. Complex Netw. 2023, 11, cnad035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).