Abstract

We introduce a Green function and analogues of other related kernels for finite and infinite networks whose edge weights are complex-valued admittances with positive real part. We provide comparison results with the same kernels associated with corresponding reversible Markov chains, i.e., where the edge weights are positive. Under suitable conditions, these lead to comparison of series of matrix powers which express those kernels. We show that the notions of transience and recurrence extend by analytic continuation to the complex-weighted case even when the network is infinite. Thus, a variety of methods known for Markov chains extend to that setting.

MSC:

94C05; 05C22; 31C20

1. Introduction

A finite or countably infinite connected graph whose edges carry positive real weights can be considered as an electrical network with resistors, and this is closely related with the intensively studied field of random walks on graphs. See the books [1,2,3,4,5], and a great number of papers, among which for example [6,7,8]. In [9,10,11,12], the wider class of networks with resistors, coils, and capacitors are considered as complex-weighted graphs. In the present note, we use the corresponding model from [12,13], i.e., we assume that is a connected, locally finite graph without loops, where each (non-oriented) edge is equipped with an admittance

where with , and . Here, is the inductance, the resistance and the capacitance of the edge, and is the inverse of the impedance. From a viewpoint of physics, s is a complex frequency, and the admittance of an edge is the complex-valued analogue of a conductance. Indeed, when is real, can be interpreted as a conductance of the underlying edge.

In the present paper we consider exclusively the case , the right half plane consisting of all complex numbers with . While this is a technical assumption which is crucial for the present approach, it is also typical in network theory: the admittance (1) is a positive-real function, that is, when ; see [12,14,15,16,17]. We set if is not an edge, so that is a function on . We call the couple a complex (electrical) network.

We introduce the admittance operator , which acts on functions as follows:

When , we see that is a stochastic transition matrix which governs a nearest neighbour random walk. This is also true when all the vectors are collinear (proportional). In particular, if they are same on each edge, then is the transition matrix of the simple random walk on the graph, independently of s. In all these cases, our network can be interpreted as a purely resistive one, where the admittance of an edge is just its conductance. The study of the network properties is then an issue of the discrete potential theory related with and the corresponding discrete Laplacian. This has its natural counterpart in the probabilistic study of the random walk (reversible Markov chain) governed by , confer the references right at the beginning.

The main questions addressed in this note are threefold:

- How can the concept of transience (resp. recurrence) be formulated?

- In the transient case, how can one construct (the analogue of) the Green function ≡ potential kernel?

- To which extent can the latter be computed in terms of power series?

We analyse the analogues of the different Laplace type equations associated with when s is complex, as compared to the well-understood case when it is real.

We first prove, resp. recall some basic estimates of admittances in Section 2. In Section 3, we introduce the Green function for finite networks with boundary, a non-empty subset of the vertex set where the network is grounded. We relate the Green function, resp., the analogues of escape probabilities, with the effective impedance defined in [12,13]. It is convenient to work with the inverse of effective impedance, that is, the effective admittance, which corresponds to the total amount of current in the electrical network. In this context, we provide first comparisons of associated power series with analogous ones for reversible Markov chains.

Our main effort concerns infinite networks, and in Section 4, we study the effective admittance both in presence of a boundary as well as the effective admittance between a source vertex and infinity. The latter leads to the notion of transience, resp. recurrence, and our main result is that this does not depend on the parameter , and that in the transient case, one always can construct a Green kernel in extension of the well-understood case when . In the final Section 5, we show how that Green kernel can be used when the network is a tree. We construct the Martin kernel and provide a Poisson type integral representation of all harmonic functions over the boundary at infinity of the tree. In the specific case of a free group, we have a closer look at the applicability of our comparison results between the complex network and the ones associated wiith positive real weights.

2. Inequalities for Admittance Operators

Notational convention. In the sequel, we shall compare the complex-weighted admittance operators with non-negative, stochastic transition operators. In order to better visualize these different types, we shall use slightly different fonts: P and will refer to stochastic transition operators—even though when .

Lemma 1.

Proof.

We first reconsider the property of being positive-real. Note that for any complex number , if and only if . We have

Next, note that

In addition, note that

Thus

and (4) holds. □

In addition to the operators (matrices) (resp. when ) we also introduce the transition operators and with matrix entries

where . From Lemma 1, we get the following comparison.

Proposition 1.

For any and all ,

Proof.

Recall that when is real, is the transition operator of a random walk. This also holds when all three-dimensional vectors are collinear, in which case is independent of the value of s. We also have the following comparison.

Lemma 2.

If (both real) then for all

Proof.

This is elementary: for real with , consider the function

For maximising, resp. minimising g, it suffices to consider , and one finds that in the simplex , the extrema of lie in the corners, whence the maximum is and the minimum is . □

Corollary 1.

For and , we have for all

(Note the particular case .) This means that we can investigate some properties of our complex-weighted network via comparison with the corresponding random walks with transition probabilities , where , or , respectively.

Notation: in the sequel, we shall write

for the collection of the stochastic matrices that come up in our context, and

3. The Green Function on Finite Networks with Boundaries

Let be a finite network. We fix a non-empty proper subset of V. This is our (generic) boundary, where the network is grounded. (This does not have to be what was introduced as a “natural” boundary of a finite graph in terms of dominating graph distances [18,19].) We consider as the interior of our graph.

If is any real or complex matrix indexed by V, then we let

We write , so that in particular, is the identity matrix over .

Definition 1.

Whenever the matrix is invertible, let

Its matrix elements are called the Green function or Green kernel of P with respect to the chosen interior .

Since each of the stochastic matrices is irreducible, it is a quite elementary fact that exists; see, e.g., [20] (Lemma 2.4). For the Markov chain with transition matrix P starting at vertex x, we have that is the expected number of visits in y before leaving the interior . Furthermore, it follows from [21,22] that also for complex weights with positive real part, is invertible for every . See in particular the proof of [22] (Theorem 2).

Definition 2.

If , then the associated normalized weighted Laplacian is the operator acting on functions by

A function is called harmonic on with respect to if

for any . Now, choose and consider the augmented boundary as well as the reduced interior. Harmonic functions come up in the following Dirichlet problem.

Our interest is in and the associated Dirichlet problem with complex weights. By [21,22] this problem has a unique solution whenever . Indeed, the function provides the (augmented) boundary data, and the solution can be given in two ways:

where (as usual) functions are to be seen as column vectors. Indeed, one easily checks that both formulas provide a solution of (7), and by uniqueness, they coincide.

The Dirichlet problem has a physical interpretation. In the electrical network model, the vertex a is the source, where the potential is kept at 1, and is the set of grounded nodes. Then is the complex voltage at the vertex x (for the complex frequency s). This leads to the following definition.

Definition 3

([13,22]). For the finite network with , the admittance between the source vertex a and the grounded set is defined by

where is the solution of the Dirichlet problem (7) with respect to .

In [22], the symbol is used for the admittance of the network. When , this is of course classical, and is the inverse of the total resistance between a and , while the resistance of a single edge is . The following is immediate from Formula (9).

Lemma 3.

Let us have another look at (8) and (9). If we replace the complex matrix by a stochastic matrix then we have the Markov chain with transition matrix P. Given and , we can consider the stopping time of the first visit in a before leaving :

For , set

Note that and that for . It is well-known and easy to prove that

the solution of our Dirichlet problem when . Furthermore,

The estimates of Section 2 suggest that we can compare the solution of (7) and related items concerning the complex network with the analogous ones for . For any (i.e., including complex weights), we introduce the power series

Proposition 2.

(i) for , let , where is the set of eigenvalues of that matrix. Then , it is an eigenvalue of , and for , each of the power series of (11) converges absolutely.

(ii) If for complex , the series

converges absolutely for every , then it is the solution of the Dirichlet problem (7).

This holds whenever for

In these cases, the series (12) is dominated in absolute value by

Proof.

(i) The subgraph induced by has one or more connected components . Each of the corresponding sub-matrices of P is irreducible and non-negative, and these matrices give rise to a block-decomposition of . By the Perron–Frobenius theorem, the spectral radius of coincides with its largest eigenvalue, which is positive real. It is , since is substochastic, but not stochastic. The maximum of the Perron–Frobenius eigenvalues of all the matrices is , and the Perron–Frobenius theorem also yields absolute convergence of for and all .

In statement (ii) above, the most natural choices for t are or . The advantage of the comparison lies in the possibility to use combinatorial methods of generating functions and paths for computing the solution of the Dirichlet problem (7).

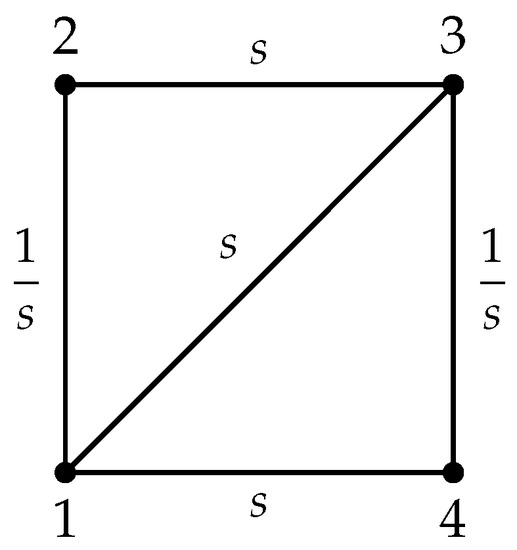

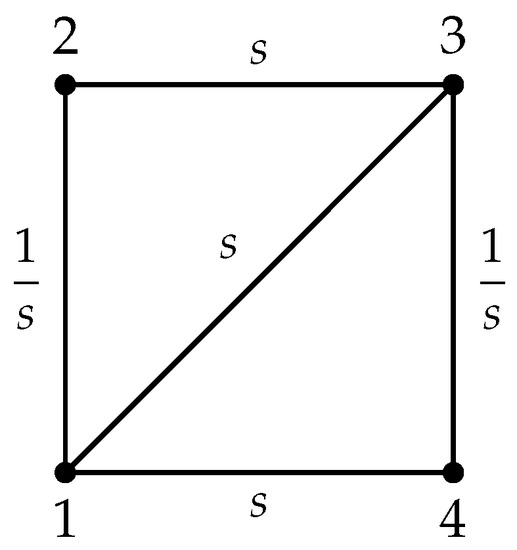

Example 1.

We consider the graph with vertex set as in Figure 1. We choose where . Along each edge, the label in the figure is its admittance.

Figure 1.

Graph, discussed in Example 1.

We have

Also, , since . We consider and , so that . For our comparison, we choose and write . Then . Also, and . The latter is better (smaller) than the former. We see that the comparison of Proposition 2 works whenever . On the other hand, the spectral radius of satisfies

One gets that if and only if , and precisely in this case, the series (12) converges absolutely, while the comparison with (resp. or ) is not useful when . Finally, if , the series (12) diverges and cannot be used for solving the Dirichlet problem. We also remark that for comparison with yields no improvement when .

4. Admittance and Green Function on Infinite Networks

The above can also be performed when the network is infinite. Recall that we assume local finiteness (each node has finitely many neighbours). In this case, the set of grounded states may be finite or infinite. It may also be empty, in which case we are considering a complex-valued flow from a to ∞. (Indeed, the boundary should rather be thought of as .) We can again consider the power series (11). When is non-empty, we get that

because is a set of absorbing states for this Markov chain. In addition, we can also consider the unrestricted Green function

and when and the series converges absolutely, we write once more . Finiteness of means that the associated Markov chain with transition matrix is transient: with probability 1, each vertex is visited only finitely often by the random process, and finiteness is independent of x and y by connectedness of the graph. More generally, consider the spectral radius

It is well known that this number is independent of x and y. It is indeed the spectral radius (norm) of P acting as a self-adjoint operator on , where the weights are

Furthermore, the radius of convergence of the power series is , and at the latter either converges for all or diverges for all . In the first of those two cases, P is called -transient, in the second case -recurrent. See, e.g., [23]. In the case of a finite network, we have of course , and the respective Green function diverges at .

Proposition 3.

(a) The Markov chains induced by are either all recurrent or all transient.

(b) We either have for all or for all .

Proof.

Let be the space of all finitely supported real or complex functions on V. With as in (17), the Dirichlet sum associated with is

By Proposition 1 and Corollary 1, the Dirichlet sums associated with distinct compare above and below by positive multiplicative constants. Thus, by [3] (Corollary 2.14) (to cite one among various sources), transience of P implies transience of Q and vice versa. This proves (a).

Regarding the spectral radius, by [3] (Theorem 10.3) (once more to cite one among various sources) we have if and only if there is such that

Besides the Dirichlet forms, also the weights m with respect to different compare up to positive multiplicative constants. This yields (b). □

Let us now consider the effective admittance of our infinite network, as defined in [12,22]. Let be the ball of radius n around a choosen the root vertex with respect to the integer-valued graph metric, and let be the set of edges whose endpoints lie in . Thus, is the subgraph of induced by . We write for the resulting finite sub-network of , where more precisely, the admittance function is the restriction of the given one to . Given the set of grounded states in the infinite network, as well as an input node , we take n large enough such that and define

Now let be the unique solution of the Dirichlet problem 7 on with respect to , as given by (8) and (9). Its dependence on s is important here. The associated effective admittance is

Proposition 4

([22] (Theorem 22)). As a function of , the sequence converges locally uniformly to a holomorphic function:

The limit is the effective admittance of the infinite network.

We are led to the following.

Definition 4.

Given the parameters and the admittances on all edges of , where , the infinite network is called transient, if for some source vertex . Otherwise, it is called recurrent.

The definition is motivated by the case , in which case we know that is the transition matrix of a reversible Markov chain, or equivalently, a resistive network, were the edge resistances are . This Markov chain is transient (i.e., it tends to ∞ almost surely) if and only if the effective conductance from any vertex a to infinity is positive (equivalently, the effective resistance is finite). Based on the previous results of [22], the following is now quite easy to prove, but striking.

Theorem 1.

(a) Transience (resp., recurrence) is independent of the source vertex a as well as of the parameter .

(b) If the (finite) set of grounded nodes is non-empty, then we have for all and .

Proof.

By Proposition 4, is the locally uniform limit of a sequence of real-positive holomorphic functions of the variable . Hence it is holomorphic on the right half plane. By Hurwitz’ Theorem (see, e.g., [24] (p. 178)), it is either nowhere zero or constant equal to zero on .

(a) Suppose that . We know already from Proposition 3 that for real , transience of the reversible Markov chain with transition matrix in independent of s. In this case it is well known that the effective admittance (or rather conductance in this situation) is . Transience then means that . It is also well known that in this case, for all . See, e.g., [2,23].

Thus, when for some and , then one also has for all and all .

The proof of (b) is analogous: when , then for all , as observed in (14). Again, in this case, the effective admittance is , and the extension to complex works as in (a). □

In the transient case (with ), if for , we have by monotone convergence

and

where , the solution of the corresponding Dirichlet problem with source node a and grounded set , see above. The analogous statement is true for , when is non-empty.

In the general case of complex , it is natural to define the on-diagonal Green kernel by

We shall unify notation, writing in both cases of (19), so that the index can be omitted when . This also applies to the following consideration of the off-diagonal elements.

Theorem 2.

For complex ,

exists for all and defines a holomorphic function of s.

Proof.

(Note that when , the sequence is constant .) We set . Then [22] (Corollary. 1) shows that for any n,

We now use the last identity of Definition 3, also proved in [22]. It yields

Note that each edge appears twice in that sum. For each , we choose a shortest path from a to x in our graph. If n is sufficently large then it is contained in . Recall that . We now use the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality:

Therefore

which of course depends on the chosen shortest path from a to x. We conclude that

We can now proceed as in the proof of [22] (Theorem. 6a). For any fixed x and a in , the sequence of holomorphic (rational) functions is bounded in any domain where . By Montel’s theorem [25] (p. 153), this sequence of functions is precompact in with respect to uniform convergence on compact sets. The limit of any convergent subsequence must be holomorphic in . Now, if is real, then

by monotone convergence. But a holomorphic function on is determined by its values on the positive real half-axis. Therefore, we have convergence on all of . □

Corollary 2.

In the recurrent case (with ),

for all and all .

This holds once more by Montel’s theorem, since for all (stochastic case).

We now can define the Green kernel of the transient infinite network by

with given by (19). (Recall that .) Then, in matrix notation,

where is the identity matrix over V. In precisely the same way, we also get the Green kernel when , and it satisfies

Question 1.

Is it true that in the transient case, the analogue of the last identity of Definition 3 holds for the infinite network ? That is, setting , then is it true that

For , this is well-known to hold; see, e.g., [3] (Exercise 2.13).

Let us take up the notation of (10), for arbitrary :

Once more, when . By local finiteness, the sum is finite. We use the analogous notation with respect to and , where , , are the vertex sets of our increasing family of finite subnetworks. We also consider the generating power series

For , we extend the definition of (16) by

Observe that deletion of the non-empty set leaves at most countably many connected components of our graph. Then each is an irreducible, substochastic matrix, so that by old and well-known results on infinite, non-negative matrices (see [26]),

is independent of , while when x and y do not belong to the same component. This means that . Recalling that , we thus get the following also in the infinite case.

Lemma 4.

If then the power series defining and thus also , as well as , converge absolutely whenever .

We now have the following comparison result for convergence of the respective power series.

Theorem 3.

This also holds when i.e., and .

Proof.

A walk in is a sequence of vertices such that for all i. Its length is k, and for , its z-weight with respect to is

We also admit , in which case the walk consists of a single vertex, and its weight is defined as 1. If is a set of walks, then

When is infinite, we require absolute convergence. For any subset U of V, and , let be the set of all walks within U which start at x and end at y, and the set of those walks which meet y only at their endpoint. Finally, the superscript refers to the respective walks of length k. Note that is finite. Then, referring to (21), for we have

The analogous identities hold when we replace V by . If is sufficiently small to yield absolute convergence, we get

and with the same z, we may again replace V by .

Now suppose that . Then “sufficiently small” just means that . We can apply this to with , and to or or with . Then with or , respectively. Then

for all and all . When, as assumed, , we get that both power series and are dominated in element-wise absolute value by

The use of weights of walks serves in particular to verify the second statement of the theorem: for , absolute convergence allows us to estimate

By monotone convergence, the last difference tends to 0. □

We would like to apply the last theorem in particular to the unsrestricted transient case () with . When s is non-real, this requires that the stochastic comparison matrix satisfies . This is independent of the specific choice of by Proposition 3, and then Theorem 3 applies when is sufficiently small. Compare this with Example 1. For general , let

Then is the radius of convergence of the power series , defined as in (15). However, contrary to the stochastic case, we do not see a general argument that this should be independent of x and y. Let us call

the spectral radius of . In the stochastic case, this is indeed the spectral radius (norm) as a self-adjoint operator, see (17). For general , we are not aware of an analogous interpretation.

Another question is the following. For stochastic , the function is the -matrix element of the resolvent operator , so that it extends analytically to , where is the spectrum of P as an operator as described via (17). Since is real, we get that extends as a holomorphic function from the disk to all with . Is there a similar property for general ?

These observations and questions are also valid when . The same is true for the next identities which we state only for empty boundary. Recall that we have for every .

Lemma 5.

For every , the following holds.

- a

- is recurrent if and only if for some and all . In this case, for all .

- b

- In the transient case, for every ,

- c

- For all with (not necessarily neighbours)

- d

- If y is a cut vertex between x and a (i.e., every path from x to a passes through y) then

All these identities hold for ; see, e.g., [23] (Section 1.D), and extend to complex by analytic extension, compare with the proof of Theorem 2. They also hold for the generating functions and with the adaptations

as long as , but it is not clear to us how to bridge the gap between these values of z and the value 1 corresponding to the statements of Lemma 5.

5. Trees and Free Groups

In this section, we concentrate on the infinite, transient case in absence of a finite set of grounded vertices. For , we shall write and for the associated kernels. The fact that we have these kernels and that their matrix elements are holomorphic functions of allows us to transport a variety of methods and results from the stochastic case to this complex-weighted one. Here, we present some example classes of this kind.

- A.

- Trees and harmonic functions

We assume that is (the vertex set of) an infinite, locally finite tree, i.e., a connected graph wihout closed walks whose vertices are all distinct. We assume that each vertex has at least two neighbours. We also assume that our complex weights are such that is transient for some ( all) . Taking up the definition of Section 3, a function is called harmonic on T if for all

In this sub-section, we shall explain that every harmonic function has a Poisson-type boundary integral representation.

We start by recalling the boundary at infinity of the tree. First of all, for any pair of vertices there is a unique geodesic path in T from x to y. A geodesic ray is a sequence of distinct vertices such that for all k. Two rays are called equivalent if (as sets) their symmetric difference is finite, that is, they differ at most for finitely many initial vertices. An equivalence class of rays is an end of T. It represents a way (direction) of going to infinity in T. The set of all ends is the boundary at infinity of T. For every and , there is a unique ray with initial vertex x which represents . We get the compact metric space as follows. We fix a “root” vertex o. The length of a vertex is its graph distance from o, that is, the number of edges of . For distinct , their confluent is the last common vertex on the geodesics and . Then

defines an (ultra)metric on , and T becomes a discrete, dense subset of the compact space . A basis of the toppology on is given by all boundary arcs

Each boundary arc is open-compact. A successor of a vertex is a neighbour y of x such that , and then we call the predecessor of y. We have

a disjoint union.

Definition 5.

A distribution on is a finitely additive complex measure ν on , that is,

for all .

Remark 1.

In [27], the following is proved. A distribution ν on extends to a complex Borel measure on the compact space if an only if for any family of mutually disjoint boundary arcs , , one has

If is a locally constant function on then it can be written as a linear combination of indicator functions of boundary arcs,

and in this case, the arcs can be forced to be pairwise disjoint. For a distribution as in Definition 5, we then set

As a matter of fact, via this definition, the linear space of all distributions is the dual of the space of all locally constant functions on , compare with [27].

In addition to Lemma 5, we now shall need the following, which is specific to trees.

Lemma 6.

Suppose that is transient. Then for every and every pair of neighbours ,

In particular,

Proof.

For real , the identity is derived in [23] (9.35). Once more, it must hold for all by analytic extension. □

Note that for arbitrary , if is the geodesic path connecting the two, then the tree structure and Lemma 5(c) imply that

Corollary 3.

In the transient case, for all .

At this point, we can define the Martin kernel as in the stochastic case:

The second identity follows from (26). Note that for any fixed , the function is locally constant on . We now get the following extension of a result which is well-known in the stochastic case.

Theorem 4.

Harmonic functions are in one-to-one correspondence with distributions on : for every harmonic function h on T with respect to (), there is a unique distribution on such that

The distribution is given by

and .

The proof is exactly as in [23] (Theorem 9.36). It goes back to [28].

More generally, for , a function is called λ-harmonic with respect to if . For suitable values of , the above extends to -harmonic functions. Namely, if for

then we can use comparison and work with and . The associated Martin kernel is then

In this case, the arguments of [23] (9.35) that lead to Lemma 6 can be applied directly via “path composition” as in that reference, and one gets

Thereafter, everything works as in [29] (with a little care concerning the slightly different notation), and one gets the analogue of Theorem 4 with as in that theorem, replacing the appearing terms with . Following the methods of [29], one also gets boundary integral representations of λ-polyharmonic functions for complex in the range of (27).

However, in general does not belong to that range, unless the stochastic operators have spectral radius strictly and is sufficiently close to 1. One of the future issues is to understand if and how the gap between and in the range of (27) can be bridged. The (finite) Example 1 indicates that this will not always be possible.

- B.

- Free groups

We consider the case when is a finitely generated group and A is a finite, symmetric set of generators of which does not contain the group identity e. The Cayley graph of has vertex set , and two vertices are neighbours if and only if . Then it is natural to require that the edge admittances (1) satisfy

so that is a non-zero, symmetric function . We then have for the total admittance at any group element (vertex) x. We get that

is a symmetric, complex measure supported by A with total sum 1. The transition operator is then the right convolution operator by , and in the subsequent notation, we shall always refer to in the place of . It is natural to consider the action on , the Hilbert space of all square summable complex functions on . The operator is symmetric, but not self-adjoint unless . We are interested in its norm and its operator spectral radius

where is the convolution power of . For the “spectral radius” defined in (24), we have

When , the three numbers coincide, with being the associated Markov chain spectral radius (16), and is of course a probability measure on .

For any , when , we get convergence of the power series . This holds in particular, when .

We now consider the case when is a free group with free generators (). We set and for our symmetric generating set. Recall that consists of all reduced words

When , this is the empty word, which stands for the group identity e. The group operation is concatenation of words followed by reduction, i.e., cancellation of successive “letter” pairs , .

The Cayley graph of with respect to A is the regular tree where each vertex has neighbours. It is very well known since [30] that in the stochastic case , and we have transience. In particular, the results of the preceding sub-section apply here. The following important result is due to [31]; for a simple “random walk” proof, see [32].

Proposition 5.

For any ,

In particular, the norm is the same as for , where . The latter is in general not a probability measure, its total mass is . Thus, we may have when s is complex. We have by Proposition 1

and since is a probability measure, its operator norm (= spectral radius) is . The stochastic transition operator induced by this probability measure is . Again, if is sufficiently close to 1, we can use the comparison method described in the previous sections, including the Green kernel at . As a matter of fact, this applies to any non-amenable group, but here we have a specific formula for the norm.

Example 2.

We suppose that and that with .

Note that then admittance means , admittance means , and admittance means . Let

Then is equidistribution on A, and it is very well known that the norm of the associated convolution operator, i.e., the spectral radius of simple random walk is . Consequently,

If then

and if is fixed, then this will be for k sufficiently large, so that the Green kernel is defined via the corresponding power series for complex z in an open disk around the origin that contains .

The same is true when k is small and the angle α is sufficiently close to 0. For example, when and then which is when .

Of course, the general estimate (28) yields a smaller range of angles α for which one obtains , like in the finite network of Example 1.

In all those cases, the power series representation of the Green kernel in a neighbourhood of allows to derive a variety of further results, such as the study of polyharmonic functions as in [29].

6. Conclusions

In this work, we have continued the research by the first author [12,13,22] on networks with complex edge-weights. The latter are admittances parametrized by a complex number s with positive real part. Building upon basic results for finite networks, our main focus is on infinite, locally finite ones. In particular, we have studied the (analogue of) the potential kernel, i.e., the Green kernel associated with the admittance operator (matrix) . When is real, that matrix is stochastic, giving rise to an interpretation in terms of transience, resp. recurrence. We have proved that this classificaton extends to our complex parameters: the Green kernel is well-defined and finite in the transient regime, and provides the network resolution, that is, the voltages at the nodes of the network induced by the given data.

The second scope has been to see to which extent one can also provide a power series representation for complex z in a suitable disk around the origin. This is performed via comparison with the stochastic case where . In the range of z where it is applicable, it will allow additional use of complex analysis methods combined with arguments of the combinatorics of paths.

There are interesting questions for future mathematical work; we mention a few:

- When , the Green kernel provides the unique solution with minimal power (energy), even in the infinite, transient case. What is the correct analogue of this fact when the edge-weights are complex? This is related to Question 1, concerning conservation of the complex power.

- When , we have that is a matrix element of the resolvent operator for the corresponding stochastic transition operator acting on a naturally associated Hilbert space depending on s. What is the operator-theoretic analogue for complex ? This is linked with the question of the range of all complex z to which the kernel extends analytically from the disk where its power series representation is valid.

Author Contributions

Writing and original draft, A.M. and W.W.; Writing, review and editing, A.M. and W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Partially funded by Austrian Science Fund FWF-P31889-N35. This work started when the first author held a position at TU Graz.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Doyle, P.G.; Snell, J.L. Random Walks and Electric Networks; Carus Mathematical Monographs, 22; Mathematical Association of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, R.; Peres, Y. Probability on Trees and Networks; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Woess, W. Random Walks on Infinite Graphs and Groups; Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics, 138; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Soardi, P.M. Potential Theory on Infinite Networks; Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 1590; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zemanian, A.H. Infinite Electrical Networks; Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics, 101; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Telcs, A. Random walks on graphs, electric networks and fractals. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields 1989, 82, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetali, P. Random walks and the effective resistance of networks. J. Theoret. Probab. 1991, 4, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomassen, C. Resistances and currents in infinite electrical networks. J. Combin. Theory Ser. B 1990, 49, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.A. Power dissipation in fractal Feynman-Sierpinski AC circuits. J. Math. Phys. 2017, 58, 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Baez, J.C.; Fong, B. A compositional framework for passive linear networks. Theory Appl. Categ. 2018, 33, 1158–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.P.; Rogers, L.G.; Anderson, L.; Andrews, U.; Brzoska, A.; Coffey, A.; Davis, H.; Fisher, L.; Hansalik, M.; Loew, S.; et al. Power dissipation in fractal AC circuits. J. Phys. Math. Theor. 2017, 50, 32520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranova, A. On the Notion of Effective Impedance for Finite and Infinite Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Muranova, A. On the notion of effective impedance. Oper. Matrices 2020, 14, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, O. Synthesis of a Finite Two-Terminal Network Whose Driving-Point Impedance is a Prescribed Function of Frequency. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Departement of Electrical Engineering, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Cauer, W. Die Verwirklichung der Wechselstromwiderstände vorgeschriebener Frequenzabhängigkeit. Arch. Elektrotechnik 1926, 17, 355–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauer, W. Über Funktionen mit positivem Realteil. Math. Ann. 1932, 106, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desoer, C.A.; Kuh, E.S. Basic Circuit Theory; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand, G.; Erwin, D.; Johns, G.L.; Zhang, P. Boundary vertices in graphs. Discret. Math. 2003, 263, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinerberger, S. The boundary of a graph and its isoperimetric inequality. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.03489. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschler, T.; Woess, W. Laplace and bi-Laplace equations for directed networks and Markov chains. Expo. Math. 2021, 39, 271–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, T.G.; Vasquez, F.G.; Tse, J.C.; Toren, E.W.; Zheng, K. Matrix valued inverse problems on graphs with application to mass-spring-damper systems. Netw. Heterog. Media 2020, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranova, A. On the effective impedance of finite and infinite networks. Potential Anal. 2021. in print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woess, W. Denumerable Markov Chains; European Mathematical Society (EMS): Zürich, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlfors, L.V. Complex Analysis. An Introduction to the Theory of Analytic Functions of One Complex Variable, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978; ISBN 0070006571. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J.B. Functions of One Complex Variable, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Seneta, E. Nonnegative Matrices and Markov Chains, 2nd ed.; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.M.; Colonna, F.; Singman, D. Distributions and measures on the boundary of a tree. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2004, 293, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cartier, P. Fonctions harmoniques sur un arbre. Symp. Math. 1972, 9, 203–270. [Google Scholar]

- Picardello, M.A.; Woess, W. Multiple boundary representations of λ-harmonic functions on trees. Lond. Math. Soc. Lect. Notes 2020, 461, 95–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kesten, H. Symmetric random walks on groups. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 1959, 92, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akemann, C.A.; Ostrand, P.A. Computing norms in group C*-algebras. Amer. J. Math. 1976, 98, 1015–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woess, W. A short computation of the norms of free convolution operators. Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 1986, 96, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).