Abstract

In this paper, a multivalued self-mapping is defined on the union of a finite number of subsets of a metric space which is, in general, of a mixed cyclic and acyclic nature in the sense that it can perform some iterations within each of the subsets before executing a switching action to its right adjacent one when generating orbits. The self-mapping can have combinations of locally contractive, non-contractive/non-expansive and locally expansive properties for some of the switching between different pairs of adjacent subsets. The properties of the asymptotic boundedness of the distances associated with the elements of the orbits are achieved under certain conditions of the global dominance of the contractivity of groups of consecutive iterations of the self-mapping, with each of those groups being of non-necessarily fixed size. If the metric space is a uniformly convex Banach one and the subsets are closed and convex, then some particular results on the convergence of the sequences of iterates to the best proximity points of the adjacent subsets are obtained in the absence of eventual local expansivity for switches between all the pairs of adjacent subsets. An application of the stabilization of a discrete dynamic system subject to impulsive effects in its dynamics due to finite discontinuity jumps in its state is also discussed.

Keywords:

cyclic self-mappings; cyclic contractions; mixed cyclic/acyclic self-mappings; uniformly convex Banach space; impulsive dynamic systems; stabilization MSC:

47H04; 47H10; 47H09; 93D20

1. Introduction

There are abundant results on the best proximity points available in the background literature for different kinds of cyclic contractions and quasi-contractions. For instance, in [1], an important investigation is performed for 2-cyclic contractive self-mappings on the union of a set of non-empty, closed and convex subsets, which do not necessarily intersect at a uniformly convex Banach space. It is also found that the sequences built with the iterations of the self-mapping converge to unique best proximity points. On the other hand, an algorithm is provided to find the best proximity points in [2]. See also [3] for some related discussion on best proximity point results for some contractive mappings in uniform spaces. Some results on cyclic quasi-contractions and strong-quasi-contractions are given in [4,5,6,7,8,9] and some of the references therein. On the other hand, in [10], quasi non-expansive results for metric-like spaces were obtained. Additionally, best proximity point theorems for -cyclic Meir–Keeler contractions are given in [11] for uniformly convex Banach spaces. Sufficient-type conditions for the existence of a best proximity point and the convergence of sequences to it are also given in this paper. Furthermore, a useful notion of cyclic orbital Meir–Keeler contractions is given together with sufficient conditions for the existence of best proximity points and fixed points in [12]. This work generalizes previous results obtained in [13], which, in turn, generalizes some mentioned results of [1] to Meir–Keeler cyclic contractions. On the other hand, some general cyclic contraction mappings of the rational type are discussed in [14,15], including a particular study of the case when the involved subsets intersect. Additionally, the problem of the existence of best proximity point results in multivalued non-self-mappings is focused on in [16,17] by using optimization tools. In particular, this problem is investigated in [17] for contraction multivalued non-self-mappings in metric spaces as well as for non-expansive ones in Banach spaces which have an appropriate geometric property.

On the other hand, a solution of a Fredholm integral equation in b-metric-like spaces is found in [18] through the involvement of a particular of a technique based on the use of rational contractive mappings.

In [19], an existence and uniqueness result for a common solution of a second-order two-point boundary differential system based on the properties of the study’s newly introduced concept of cyclic -contraction pairs. Additionally, best proximity results are proved in that paper concerned with mappings defined on proximally complete pairs of subsets of a metric space. This research extends a previous one reported in [20] on the proposed new concept of -contractions. It is also proved in [20] that any -contraction self-mapping possesses a unique fixed point in a complete metric space.

It is well-known that sometimes differential or difference dynamic systems can be subject to different parameterizations which describe the dynamical behavior around different operation points. When the parameterization of the differential system changes abruptly, there are discontinuities in the differential equations which describe the system dynamics. If the state has finite jump-type discontinuities, then the differential system is impulsive and vice-versa. See, for instance, [21]. Therefore, some typical control problems, such as, for instance, controllability or stabilization, become much more difficult to solve in the presence of either state discontinuities or impulsive controls at certain time instants. Some phenomena are sometimes associated with parameterization jumps or state discontinuities related to practical requirements. This often happens, for instance, in dynamics of chemical engineering processes along different phases of processing and monitoring a complete complex process or in discrete dynamic systems when the sampling rate is non-uniform, as in [22,23]. Therefore, the stabilization problem under either configurations or state switches has received important attention in the study of continuous-time, discrete-time, hybrid and time-delayed systems. Close problems often appear concerning the properties of the controllability and reachability of dynamic systems. See, for instance, [24,25,26,27,28] and some of the references therein as well as the recent works [29,30,31,32,33,34].

In this paper, we define and study a very general class of multivalued self-mappings defined on the union of a finite set of subsets of a metric space which is of a mixed cyclic and acyclic nature. The mixed nature is that the mappings can generate iterations in one of the subsets before eventual switching to their right adjacent one. The main purpose of defining and addressing such a mapping is to have in mind its potential application to the stabilization of dynamic systems submitted to state discontinuities in their state, which causes the differential systems of the equations which describe their dynamics to become impulsive at certain time instants.

The considered self-mapping has the following specific characteristics in the most general formal setting:

- (a)

- It is multivalued since it applies to each subset in the union set of itself with its right adjacent one and each domain point can have, in general, several image points in both such subsets;

- (b)

- It is of mixed cyclic and acyclic nature since it can perform several consecutive iterations within each of the subsets before switching to its right adjacent one;

- (c)

- The number of such consecutive iterations within each of the subsets before switching to its right adjacent one may vary dynamically around each cycle of complete running of the self-mapping on all the subsets. This fact facilitates the formal use of monitored iteration-dependent switches in stabilization applications;

- (d)

- It is not necessarily contractive between all the pairs of adjacent subsets of the configuration, although the most relevant properties are proved if the switches related to at least one of the pairs of adjacent subsets are contractive;

- (e)

- It can have also local non-expansive (being, furthermore, non-contractive) local properties between some of the pairs of adjacent subsets or even local expansive ones for some of the switches between the pairs of adjacent subsets;

- (f)

- The contractive, non-expansive or expansive constants associated with each of the subsets and in-between adjacent subsets which characterize the mapping are not necessarily identical and the distances between each pair of adjacent subsets are not necessarily identical either. Some of the results concerning the boundedness and the asymptotic boundedness of the distances between orbital points generated by the self-mapping iteration do not require specific conditions such as closeness or convexity on the involved subsets of the metric space or the uniform convexity of this one.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives a preliminary study for the mixed 2-cyclic/acyclic multivalued mapping (that is, being defined on two subsets of the metric space). The asymptotic boundedness of distances in the orbits from initial points in the union of sets are proved under certain global contractivity conditions of the whole mapping for groups of non-necessarily constant numbers of consecutive iterations. That property is proved without requiring that the involved subsets are closed. Section 3 extends and completes the former results for mixed -cyclic/acyclic multivalued mappings. Some specific related results are presented in Section 4 on the convergence of iterated sequences to best proximity points. The particular cases focused on in this section are that of the absence of local expansivity and the one of potential statement of monitored switching between adjacent subsets. Such a monitoring process is governed by a switching rule which operates in tandem with mixed -cyclic/acyclic self-mapping and which establishes the iterations for switching between adjacent subsets to take place. Afterwards, some numerical examples concerned with an application for the stabilization of a discrete dynamic system subject to impulsive controls with monitored switching are discussed in Section 5. Finally, our conclusions end the paper.

Notation

- denotes the closure of a set and is the cardinal of the set ;

- if is multivalued then is the image set of through which is, in particular, a singleton if is single-valued. In the same way, is the image set of in through ;

- distances between points and distances between sets under a metric in a metric space are denoted with the same notation, i.e., for and for being subsets of .

2. Problem Statement for Two Subsets of Metric Space

Following [1], we define the following concepts for non-empty subsets , where is a metric space:

Thus, and . Note that, for the sake of simplicity, the distances between sets and the distances from a point to a set via the -metric are referred to with the same notation as the one used for distance between points. The sets of best proximity points and are non-empty if is compact and is approximatively compact with respect to , that is, every sequence , such that as for some , has a convergent subsequence. It can be pointed out that there are examples where or may be empty even if and are non-empty. See, for instance, [2,3]. The following definition is quoted from the cyclic mappings in [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] and renamed “ad hoc” by indicating with “2” the particular cyclic context involving just two subsets of the metric space and the contraction constant.

Definition 1

([3,4,5,6]). Let and non-empty subsets of a metric space and let , such that , and and . Then, is said to be a -cyclic contraction if, for all and and some ,

In the same way, ifthenandis non-expansive and if, thenis expansive.

We now investigate some properties of boundedness and convergence of sequences of a multi-valued self-mapping , where with non-empty sets and being subsets of a metric space . Note that self-mapping is not, in general, cyclic since the constraints and do not hold in such a way that each generated sequence through from any initial point in can have several successive iterated points in either or before switching either to or to . Therefore, the mapping is mixed cyclic and acyclic. Assume through the manuscript that satisfies the subsequent stipulations for :

for some if for some ,

for some if for some ,

for some if for some provided that ,

for some if for some provided that ,

for some if for some .

Then, given , we can choose for , which satisfies one of the inequalities (3) to (6). The constraint (2) implies that each point in has at least one image in and one image in through .

It is also assumed in the sequel that the best proximity sets of with respect to ; are non-empty, that is, ; .

The following technical assumption is made through the manuscript:

Assumption 1.

The metricof the metric spaceis assumed to be homogeneous.

The above assumption is not necessary for the whole set of obtained results, in particular, for those referred to the upper-bounds of the distances associated with the mappings through the iterated calculations. However, it facilitates some of the mathematical proofs, in particular, those referred to excluding potential asymptotic unboundedness of distances from the implication that bounded distances can imply that of the sequences of points of involved in the calculations of such distances. In particular, it can be pointed out that homogeneous and translation-invariant distances are norm-induced distances. A metric is said to be homogeneous if for and . It is said to be translation-invariant if ; properties are jointly fulfilled, for instance, by norm-induced metrics on linear or vector spaces since:

Typical widely-used metrics in applications such as, for instance, Euclidean and taxi-cab metrics fulfill those joint properties. Note also that the property that distances can asymptotically grow, leading to infinity limits (if some of the involved sequence of the points of involved in their calculations is unbounded), is intuitively attractive and very useful in practical problems. This property is fulfilled by many usual distances, such as Euclidean distance, taxi-cab distance, Minkowski’s distance and others, but it is not inherent to the definition of distance. For instance, the discrete metric is never unbounded, irrespective of the involved pairs of points, since it is not greater than unity by definition. However, a homogenous distance is characterized by the property so that and to infinity as . Note that homogeneous distances are termed as absolutely homogeneous distances in some of the background literature.

Remark 1.

The above constraints (2)–(7) imply that the mapping is expansive on, contractive onand cyclic contractive for switchings between both sets if both. If, then the switching fromtowhen building the iteration step is not necessarily contractive, but it is non-expansive. Note that;;for any. In particular, (3) is expansive, which applies to the images inofof the couples of the pointsin, while (4) is a contraction which applies to the images inofof the couples of the pointsin. Equation (5) is non-expansive, since, in particular, contractive if, for the images of two pointsin, which are one inand the other one in. In the same way, the non-expansive (6) applies for images of the two pointsin, which are one inand the other one in. Finally, (7) is a non-expansive or contractive rule which applies to points, each in one of the setsandwith images each in one of the sets but not necessarily alternated with respect to each of the original points. In the particular case that the images are alternated, the mapping is also cyclic according to (7).

Remark 2.

The various orbitsof initial pointmight be generated according tofor some,withbeing subject to one of the stipulations (2)–(7) for each successive iteration.

Note from (5) and (6) that ifor if, then switches ofthe formdo not take place if, implying that bothandare either inor in, since, in this case, (5) and (6) would lead to the contradictionifor, respectively,. In order to also allow switchings ofwhen(requiring necessarilyor) so that the constraintis removed from (5) and (6) while keepingto be non-expansive at, except if, the stipulations (5) and (6) oncan be changed to the following ones:

Note that, sinceimplies that bothandare in the same subsetor, Equation (9) is identically expressed as follows:

In the following, the main results are conducted under the stipulations (2)–(6) for the sake of exposition simplicity. Let us denote the sequel as the -iteration constant for a sequence generated from any initial point in and which can take any of the values , , and . Then, the following result holds for boundedness and convergence of distances between iterates of an orbit of for some sequence ; .

Theorem 1.

Consider the orbitsofgenerated according tofor some,withbeing subject to the stipulations (2)–(7). Then, the following properties hold:

- (i)

- wherewhere:

- (a)

- andif;,

- (b)

- andifand;,

- (c)

- andifand.

- (ii)

- If Assumption 1 holds, thenis bounded forsuch thatis finite and

- (iii)

- If Assumption 1 holds andis finite, thenis bounded if it does not exist, a strictly increasing sequence of positive integerswithfinite such that;. Otherwise, if one such a sequenceexists, thenis unbounded.

- (iv)

- Under Assumption 1, assume thatis finite. Thenis bounded if the following constraints hold:(C1) it exists a finite set or a sequence, withbeing finite andsuch that(C1a) the incremental sequenceis bounded if, andis bounded if, whileis infinity if(implying that) andunder the necessary condition;. A sufficient condition for (14) to hold ifiswhere(C2) Furthermore, ifthenfor some positive integer.

- (v)

- Ifis finite for a givenand;thenis bounded andas. The same property holds for the sequence of distances between consecutive points on an orbitifis such thatis finite withforand;for some finite nonnegative integer.

Proof.

One obtains from (2)–(7) that

where is the identity map and

- (1)

- and if with for some .

- (2)

- and if for some with

- (3)

- and if with

In the same way, one obtains by taking ,

where and for and and if and or or if in view of (5)–(7) depending on the allocations in or in of the images of the original points and on the fact that those original points are in the same or in distinct sets or according to (5)–(7). Then, one obtains recursively from (17) that:

with and and one obtains (11), from (20) via (14), by taking , some . Then, properties (i) and (ii) follow directly. Property (iii) is direct since if exists with , then is unbounded since it has one strictly increasing subsequence . Otherwise, if no such a sequence exists such that , then is bounded if is finite for some and some , being the second point of the orbit of since all its subsequences are bounded. To prove property (iv), note that if is bounded, then it has (at least) a finite maximum at a finite iteration step . If such a maximum is zero, then the sequence is identically zero and the proof follows directly. Assume now that , while it also has to exist that either a finite set or an infinity sequence of nonnegative integers , with the incremental sequence being bounded if and being bounded and , is bounded if so that

for some since is the finite maximum of consecutive distances between points of the orbit of the initial point , where and are defined in (17). In order that (21) holds, the following constraint is required:

Since with if and only if , that is, if and only if ; and then (22) also holds under the stronger condition:

then, if ; and, furthermore, ; if . Property (iv) has been proved. The proof of property (v) follows directly from property (iv) since there is no switch from to , then , ; , as . The same property also holds for any orbit which does not contain points of the mapping iterates in , after some finite number of iterations, for any given initial point in such that is finite generates the sequence. □

Remark 3.

For the distance sequences generated from any finite initial point, some intuitive consequences of Theorem 1 are:

- (1)

- It is not relevant that the setsandbe necessarily either bounded or closed for the eventual boundedness of any iterated sequence of distances generated from any pointsuch thatis finite for someand some. This is an “a priori” hypothesis, equivalent in fact to the initial distance to be defined in order to give conditions for the sequence of distances between consecutive iterates not to be unbounded.

- (2)

- The distance sequences is unbounded ifand, i.e., all the iterations are infrom (3) since, from (14),and;andas. The same happens if all the iterations are inafter a finite iteration step.

- (3)

- The distance sequence is bounded and convergent to zero ifand, i.e., all the iterations are infrom (4) since, from (14),and;andas. The same happens if all the iterations are inafter a finite step.

- (4)

- The distance sequence is bounded if, after some finite iteration step, each member alternates switches iteration-to-iteration fromtoand fromtosince the distance is bounded after the finite numberof iterations prior to the first switching (if the initial generating pointis such thatis finite) and since the mappingis both non-expansive and cyclic for the successive iterationsfrom (5) and (6) sinceforso that

- (5)

- In order for (15) to hold for some sequencewithfinite,, with the incremental sequencebeing bounded such that the distance sequence boundedness conditions (15) or (16) hold, it is sufficient that:

- (a)

- either the mapping becomes cyclic after a finite number of steps (see the above Remark 3(4)), or

- (b)

- it remains confined to iterations withinafter a finite number of steps or, if there are non-successive switches fromtoand fromto, then switches are ruled to satisfy the conditions (15) or (16) of Theorem 1 (iv).

- (6)

- The condition C2 of Theorem 1(iv),if, means that, after a finite number of iterations, the successive iterates only are inor in the best proximity set ofwith respect to. In other words, if infinitely many iterates ofare alternated inand, then, that is, the sequenceis infinite to ensure the boundedness of the distance sequence.

The following result gives explicit conditions on particular conditions for successive iterates for Theorem 1 (iv) to hold:

Proposition 1.

Under Assumption 1, assume also thatis finite for a givenand consider orbitsofgenerated byfor some,, withbeing subject to the stipulations (2)–(7).

- (1)

- Letbe the total number of (non-necessarily consecutive) iterationsfromto;for iteration indices,according to (3) and (4);

- (2)

- letbe the total number of iterations fromtoforfor iteration indices,satisfying the constraints (5) and (6); and

- (3)

- letbe the total number of (non-necessarily consecutive) iterationsfromtoand fromtofor iteration indices,according to (7).

Then,is bounded if, for some real constant, there exists a non-negative real sequencesuch that

ifor ifand;, and

ifand;.

Proof.

Note from (12) and (17), and ; in Theorem 1 (iv) that

subject to the constraint:

where are the respective non-necessarily consecutive numbers of iterations for , ; satisfying the constraints (1)–(7). Define also:

with , , ; , which allows us to rewrite compactly as

after rewriting the upper-bounds of (2)–(7) under the equivalent forms:

since if and if ; .

The constraint (15) with of Theorem 1 (iv) for guaranteeing the boundedness of the distance sequences are , from (26) by taking into account that , and for , or equivalently from (24), provided that , that is, , or under the strict inequality , equivalent to (25), provided that both , that is, , and , so that in (27), implying that there is no crossed iteration from to or vice-versa. □

It turns out that Proposition 1 still holds under the non-strict inequality (24) if the total number of crossed iterations from to or vice-versa are finite. Thus, one has the subsequent direct extension of Proposition 1:

Proposition 2.

Under Assumption 1,is bounded under the stipulations of Proposition 1 if, for some real constant, there exists a non-negative real sequencesuch that (24) holds andor, ifand.

It turns out that, in order for the sequences of distances between consecutive points of any orbit for some initial point , it is necessary that can have image points in for such a .

Proposition 3.

A multi-valued mappingwhich has bounded distance sequences according to Proposition 1, or to Theorem 1(iv), for any orbitfrom some given initial pointhas to fulfillfor some finite integer. The above property holds for any orbitfrom any given initial pointif and only iffor finite integerdepending on each.

Proof.

It follows since if for , and any finite non-negative integer , then , since as so that it is not possible to fulfill either the constraints (24) and (25) of Proposition 1 or the conditions of Theorem 1 (iv). □

Definition 2.

The partial orbitof the orbitofthroughis an ordered set defined recursively byfor somewith;.

Remark 4.

Note that ifbelongs toandbelongs to;, then the partial orbitwith;has a switch of set in the generation of its last member. Thus, one of the non-expansive constraints (5) or (6) has been used to incorporate the new element of the orbit. Note also that unconditional switchings fromtoor vice-versa are not allowed at any arbitrary iteration ifis single-valued. Therefore, the results of Theorem 1 and Propositions 1–3 concerning the boundedness and the convergence of the distance sequences cannot be monitored towards the fulfilment of Theorem 1or Propositions 1–3.

It turns out that the particular cases and are also covered by the above more general formulation. This suggests that switchings from to are expansive as they are the successive iterates within , while switchings from to are contractive as they are the successive iterates within . The lost on non-expansivity of switches from to does not modify the essence of the above given results. This is seen in short as follows. Assume that and take , and that satisfy:

The necessary condition is compatible with the above upper-bound since . At the same time the fact that the mapping is expansive from to such that

agrees with , while it keeps as locally non-expansive if , i.e., if , and under the necessary assumption that for . Thus, once a switching to holds which is expansive if , it can remain in leading to the orbit to be contractive in and converging to some if and is closed.

3. Problem Statement for p Subsets of a Metric Space

Now, define non-empty subsets with for and , where is a metric space and consider a self-mapping . The terminology is used such that and are adjacent subsets, is the right adjacent subset to , while is the left adjacent subset to ; . In order to keep a simple notation, we will denote in the sequel by for any given the restricted multivalued map from a set to the union to itself with its right adjacent one .

Through this section, the main ideas of the former section are kept but, in order to simplify the exposition, the following assumptions are made:

(A1) The multivalued mapping is mixed -cyclic/acyclic in the sense that for with such that for each and each , with .

(A2) A finite number of iterated images of in may happen before switching to its right adjacent subset when constructing an orbit. That is, a partial orbit with initial point in is , where for , and . If is infinity, then is the terminal set with no further switchings of to its right adjacent subset.

The number is admitted to be varying for each cycle of running all the subsets ; .

(A3) with and being pair-wise disjoint defined by:

which are indexing the disjoint subsets , and , where are contractive, non-expansive being non-contractive and expansive, respectively, where:

- (a)

- the contraction condition is defined as follows:

- (b)

- the non-expansivity condition is defined as follows:

- (c)

- the expansivity condition is defined as follows:

- (d)

- The switching from to its right adjacent subset in (33), and in (31) and (32) if , are performed only provided that if for any .

Note that, in order to simplify the exposition, the contractive or expansive constants for iterations within subsets are assumed identical to their counterparts related to switching from a subset to its right adjacent one. Note also that, although contractive conditions are also inherently non-expansive, we consider each one of them, in the above characterization, specifically as “contractive· or as “non expansive” according to the constant being either less than unity or unity. Thus, by convenience, the set is not included in the set so that . It turns out that from the above constraints the restricted images of (i.e., the mapping from the respective subset Ai to itself) are contractive, non-expansive and expansive, respectively. However, the respective restrictions to each reach right adjacent subset are not guaranteed to be contractive or non-expansive since can exceed unity. This tries to reflect the practical fact that switching actions from a subset to its right adjacent one can have an instability cost due to the switching itself even if iterations within that right adjacent subset are contractive. We can think here, for instance, about the modeling through ordinary differential equations of a dynamical system subject to impulsive controls which can make the state norm to grow by huge amounts at the sampling instants where impulses happen.

Note that the condition if for switching to any ensures that the upper-bounds in the conditions (31)–(33) are well posed since for any .

Proposition 4.

A sufficient condition guaranteeing that the expansivity conditionis well posed is that, for any, Assumption A4 below holds:

(A4) if

Proof.

It follows since, for the first inequality of (33) to hold in the worst case, that is, for the largest possible value of for , which is , it is sufficient that for : which gives the result. □

Remark 5.

Since we will usually work only with conditions for the boundedness and convergence of sequences, only the upper-bound of (24) will be addressed through the constantsand. However, note that the upper-bound does not guarantee directly that the mappingis expansive but just that it is not guaranteed to be non-expansive.

Now, consider an orbit from an initial point such that , provided that for some ; . Denote the partial orbit of on for some and a given as . Then, all the points of the partial orbit belong to for some with eventual iterations within of the various sets , for each , together with eventual iteration switches to their right adjacent ones.

The following result holds which implies that the sequence of distances is bounded provided that is non-empty, that is, there is at least one subset for , where is contractive, according to (31), and that each cycle has a sufficiently large number of iterations in .

Theorem 2.

Under Assumptions A1 to A4, the following properties hold:

- (i)

- Consider a complete cycle ofconsecutive iterations on all the subsets,on the integer intervalstarting fromfor some, someand somewhich hasconsecutive iterations withinbefore switching tofor each. Thus, one has for the partial orbitonthe following relation of distances:under the identities,and, if;, whereand

- (ii)

- Assume, in addition, thatwithfor the givenis the sequence of integers with the associated incremental sequence, which contains element-to-element the number of iterations, each of them being associated with a complete cycle on all the subsetsfor, that is,withandwherecontainsswitches between right adjacent subsets andis the total number of switches which have happened since the iteration.Then, the distancesandfor, related to the two pairs of elementsandof the partial orbiton, satisfy the constraints:for; some,, where:

- (iii)

- Assume furthermore that, for the sequenceof property (ii),, for some, and assume also thatwithfor the givensuch thatfor someand assume also thatis finite. Then,. Ifand if

- (1)

- eitherand(i.e., there are infinity many switches from a subset to its right adjacent one but not infinitely many iterations in a subsetprior to switching to the right adjacent one), or

- (2)

- ifand there are infinitely many iterationswithin in a final setbeing either non-expansive (including the contractive case) subject, furthermore, to,

Then the sequence of distancesfor adjacent points of the orbitis bounded. Furthermore,

As a result, all sequences of distances;are also bounded.

Proof.

Properties [(i) and (ii)] follow directly from the application of (31)–(34) where is arbitrary, with , being finite and is such that , and , with is the sequence of complete iterations along the subsets . Property (iii) follows since (42) under the constraint yields . Furthermore, if and , then the sequence of distances cannot be unbounded for intermediate iterations within the sequence of finite intervals so that it is bounded. It also follows from (38) that

and (43) holds since as . A similar result is found if , that is there is some subset for where infinitely many terminal iterations take place with no later switch to its right adjacent one under the assumption that , that is, the terminal iterations are non-expansive (eventually contractive) with . □

Note that the conditions and are key stipulations for the boundedness of the distances between consecutive points of the orbit in Theorem 2 (iii). This can be fulfilled with at least one of the subsets in and a sufficiently large , for , compared to being dependent on the value of the contractivity condition . On the other hand, note that any distances for any finite are bounded from the use of the triangle inequality for distances and the above proved property for the given since for some finite real constant :

for some and some . However, according to (43), the above result also holds for any (even infinity) .

Example 1.

Note thatin (43) has to be not smaller than the corresponding distance between adjacent subsets provided that the involved points belong to adjacent subsets. For instance, assume that,and, that is, the mappingis expansive inand contractive in. Assume that all the cycles have the same number of iterations en each of the subsets taken aswithinandwithin. Under Theorem 2 (iii),for each cycle of iterations on both subsets to be contractive. Identifyingwithwith one of each points within one subset, one obtains from (43) that

under the necessary assumption that, which, together with, yields, subject to.

Now, consider the alternative problem without iterations within neithernorso that. In this case,and an “ad hoc” redefinition ofleads tounder the necessary condition, which holds sinceif. It turns out that the maximum allowableis smaller than the one for the above case.

Example 2.

Considerfor subsetswith none internal iterations within any of the subsets before switching to each right adjacent subset, i.e.,for, subject toandfor. Assume four possible cases to guarantee that:

- (a)

- ;with. Then,which holds trivially identical tosince.

- (b)

- can be eventually distinct subject toso thatwhich holds iffor which it is sufficient that, since,, which holds directly since.

- (c)

- so thatso thatwhich holds iffor which it is sufficient, since,, which holds directly since.

- (d)

- Now assume thatforso that the redefinediswhich is a known property of-cyclic contractions.

Example 3.

The convergence of the distances to the best proximity points is not possible if the mapping is expansive for switching actions from a set to its adjacent one, and there is one expansive contraction that is not possible for the case of only two setsand, i.e.,when the closures of such sets (or themselves if they are closed) do not intersect; i.e., the constraintis not feasible. Note that at the limit for infinitely many iterations, the subsequent relations

should hold, that is, which only holds if and only if, i.e., if and only ifsince.

If there are three involved sets,and, i.e.,, with one expansive mappingfor the switches fromto, while those fromtoand fromtoare contractive, one has the following limit constraint relations to guarantee the eventual convergence of the distances forif,:

implying thatso that either, that is,, orso thatso that, even, if, then, and then the convergence of the distances toor that of the involved points to the best proximity points ofandis not possible.

Note that Theorem 2 (iii) also implies the boundedness of the elements of any orbit , what is now termed as such an orbit being bounded, as it is now specifically addressed:

Theorem 3.

Under Assumptions A1 to A4, consider any orbitwith bounded initial point,. If Theorem 2 (iii) holds, then such an orbitis bounded.

Proof.

It is obvious from generation of the orbit , for some given initial point , that for some , and any given finite . The partial orbit is bounded since is finite and is bounded. Since is finite then is finite. Now, assume that there is some sequence which has an unbounded subsequence with . Since , take to be sufficiently closer to by taking the advantage that the incremental sequence with , for the given , is bounded and one obtains also from (43) that if the subsequence is unbounded, then the following contradiction holds since for some and some finite , so that is finite:

Therefore, any sequence is bounded. □

Note that Theorem 2 (iii) assumes that is finite as an “a priori” stipulation for the boundedness of the sequence of distances in-between adjacent elements of the orbit . However, Theorem 3 assumes that the initial point of the considered orbits is finite in order to guarantee that the partial orbit of a finite number of elements starting by is bounded. This assumption would not be invoked if the subsets for were bounded.

4. Some Particular Results: The Case of Non-Expansivity and That of Monitored Switching

It is proved for in [1] (Lemma 3.8 based on Lemma 3.8), irrespective of the properties of the single-valued contractive 2-cyclic mapping , that if is an uniformly convex Banach space and the subsets and of are non-empty, closed and convex then:

Such a property holds irrespective of the mapping being single-valued or multivalued and without invoking whether it is contractive or not. It is also proved in [1] that if, furthermore, is single-valued and 2-cyclic contractive then there is a unique best proximity point such that and if then and , and and are Cauchy sequences.

The subsequent result firstly establishes some best proximity results in the case that there are no iterations of the mixed -cyclic/acyclic multivalued mapping , , within each of the subsets provided that the complete metric space that the subsets for belong to is a uniformly convex Banach space and that the mapping is contractive at least from one switching of one of the subsets to its right adjacent one in the event that it is not expansive from any of the subsets to its right adjacent one. Since there are no iterations between each subset before switching to its right adjacent one, the -cyclic/acyclic mapping is, in particular, a multivalued -cyclic mapping due to the absence of internal iterations within each of the subsets. Later on, in the second property of the theorem, a new result generalizes the results to the case when has iterations within the subsets before switching to the right adjacent ones (i.e., it is of cyclic/acyclic nature) under certain conditions of Theorem 2.

Theorem 4.

Assume that:

(A1)are non-empty closed and convex subsets of a uniformly convex Banach space.

(A2) Assume thatis a mixed-cyclic/acyclic mapping, subject to;with respect to the norm-induced metric;, by the norm of, which satisfies (31) and (32), under the constraints,(so thatand),;,,;,such that for eachand each,with;.

Then, the following properties hold:

- (i)

- There is a best proximity pointinwith respect to, that is,;. Furthermore, for any, if, thenforis a best proximity point inwith respect to, andis also a fixed point inof the composite mappings;.

- (ii)

- If Assumption A2 holds under the subsequent generalizations: (a);, for some givenwith,being strictly increasing and the incremental sequencebeing uniformly bounded and covering a whole cycle of iterations covering all the subsetsfor, such that for eachand each,with,andin the case whenfor some; andwhere.

Proof.

Since , it exists for some . Consider, with no loss in generality, initial points of the sequences and ; generated by under the constraint ; , which makes become ; . The choice of and in is without loss of generality since for any given , there are nonnegative integers such that one can fix and for any prefixed subset of . Since , , and , it turns out that so that:

Then, and for any given , with and for any . Since is a uniformly Banach space, and are closed and convex and , one concludes also that and that is a Cauchy sequence. It also holds that is a fixed point of the composite mapping , then . As a result, ; and is a fixed point of in and also a best proximity point in of since because ; implies that ; and the given such that .

and that are convergent and Cauchy sequences; . Note that, since if since is closed, and the sequences and for any given fulfill that and , one obtains that for any given and is convergent to since is closed. Continuing with this process, one obtains that ; . Assume that . Then, one obtains that and with convergent sequences and . However, then which is a contradiction to then . Continuing in the same way with this process for , one concludes that are unique best proximity points in of , which are fixed points of the composite mapping . As a result, property (i) is proved.

To prove property (ii), note that under Assumption 1 and the given generalized Assumption 2, and, since ; and , then

since then for some real constant and any given . According to Theorem 2, Equations (35) and (36), one concludes in the same way as getting (48) and (49) that, for any given ,

so that

The remaining of the proof of property (ii) follows in a similar way to that of property (i). □

Remark 6.

Ifin Theorem 4 so that values of the constantsforare compensated by other contractive constant valuesforwhile (47) holds then (53) and (54) in Theorem 4 (ii) still hold. H, it cannot be proved, in general, the convergence of sequences to the best proximity points of adjacent subsetsandforof.

The statements of the given results until now consider the event that the number of consecutive iterations within each subset before switching to is either pre-designed, including a fixed number of iterations, eventually being iteration-dependent, within each , or monitored in the sense that the switching be decided by a switching rule such that if , then there is not a switch at the -th iteration of from to for some and the partial orbit of any fulfills with satisfying , .

On the other hand, if , the mapping switches from to at the -th iteration so that the partial orbit exhibits a switch in the allocation set from to .

The monitored strategy of switching between the subsets ; of according some rule is of interest in certain applications. For instance, if the stabilization of a discrete dynamic system cannot be achieved for successive iterations within a set because of inherent instability within it, then it is convenient to assign it along certain transients. Additionally, an instability problem could arise if a discrete system becomes unstable under its current parameterization. This drawback can be eventually solved by generating switches in its state, together eventually with parameterization switches, which lead again the trajectory to a stable region. See, for instance, [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. The following immediate result establishes the convergence of sequences to a fixed point of any subset , where the mapping is contractive, under any monitored switching rule which confines the successive iterations within such a subset after a finite number of iterations.

Theorem 5.

Consider a pair, whereis a self-mapping under assumptions A1 and A2 of Theorem 4 andis a monitored switching rule between a subsetand its right adjacent one;. Assume that for some finite,;such that. Then, any sequencewhereis a fixed point offor any given.

Proof.

It is obvious since the monitored switching rule determines that any partial orbit of the orbit is confined within , which has a fixed point from since is closed and is closed for any . If is single-valued, then is unique since is closed and convex. □

5. Numerical Simulations

This section is aimed at illustrating the previous obtained results concerning the boundedness of sequences and orbits of cyclic/acyclic contractive/non-contractive self-mappings. To this end, the case of a discrete-time dynamical system is discussed. Thus, consider the dynamic system given by:

; . The system is described by the self-mapping . This self-mapping has a different behavior depending on , or , generating the following three subsets:

with

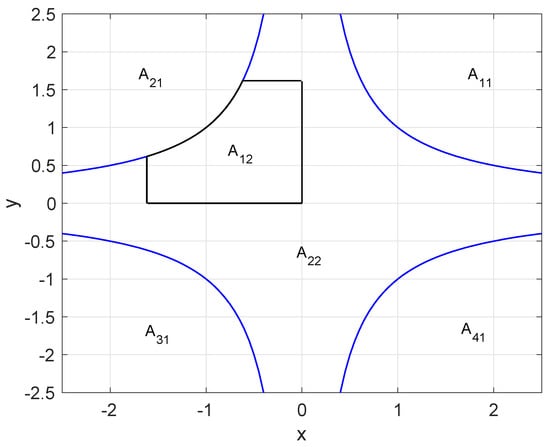

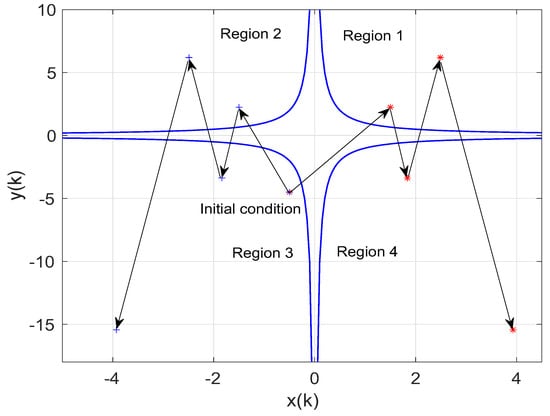

The set A1 is disconnected and can be represented by the union of four connected disjoint subsets. These subsets are called , , and as is displayed in Figure 1 where the blue lines depict the hyperbola . On the other hand, the set A2 is connected and it is split into two subsets, namely and , as in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Different regions on the plane for the self-mapping (55) and (56).

Note that and are disjoint unbounded subsets of , with and being open and being closed. Since those sets are disjoint, the sets of best proximity points between each pair of them are empty, but because of the asymptotes defined in blue lines which define the boundaries, the distances between adjacent subsets are zero. Note that is a self-mapping on so that and . Note also from (55) and (56) that, for any given initial point , the Euclidean distance between consecutive points of iterations through satisfies with ; :

which becomes asymptotically unbounded as if , or if , as . We can define the contractivity-, non-expansivity- and expansivity-point-dependent constants as:

Thus, the Euclidean distances between consecutive points of arbitrary orbits being calculated via iterations through from finite initial points in are not necessarily asymptotically bounded. Then, some monitoring of switching between the three subsets , and should be performed to guarantee their asymptotic boundedness. Note the following facts:

Fact 1.

One obtains from (55) and (56) thatand;. Therefore, the second semi-open quadrantofis unreachable (or forbidden) for any sequence solution of (55) and (56) except for initial points. As a result, there are forbidden subsets ofand(see (57) and (58) and Figure 1) which are unreachable except for the initial conditions.

Fact 2.

If, thenandsince, and then;. Thus,since;. Additionally,and;imply that;. Then, the sequenceis non-positive and convergent to zero under a weak contraction. Sinceis non-positive convergent to zero,is non-negative and convergent to zero from (55) and (56).

Fact 3.

( is weakly contractive inand a strict contraction in): One obtains from (55), (56), (60) that

Sinceis convergent for any initial condition in, from Fact 2, for any given real constant, there is some finitesuch that;. By checking the inequalitywith and sinceis a convex parabola, one concludes thatwithif. As a result, any sequence, with, is non-positive with strictly decreasing modulus and, from (55) and (56),is non-negative and strictly decreasing, both sequences being convergent to zero. This implies thatis weakly contractive inand it enters intoafter a finite number of iterations, whereis a (strict) contraction with the solutionfor any.

Fact 4.

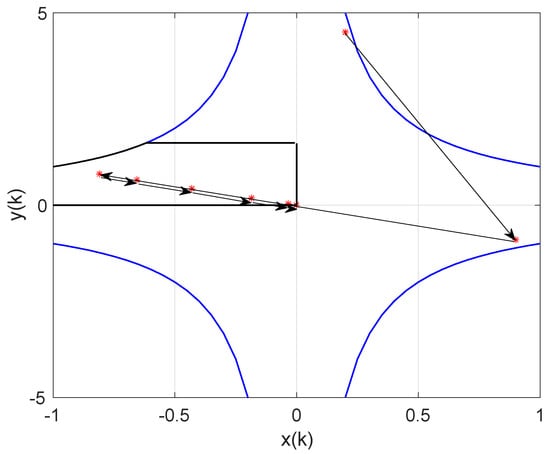

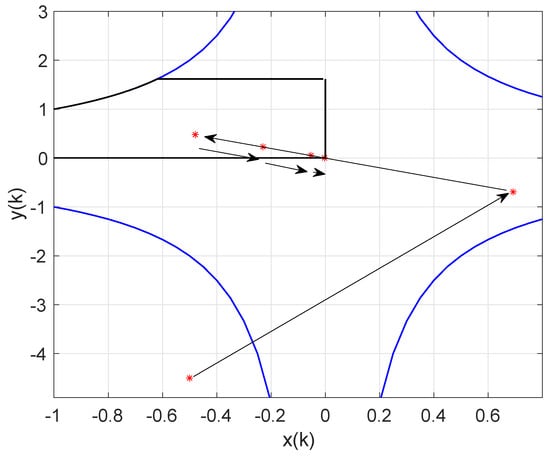

(is a fixed point ofand a global attractor of the solution for any initial condition in). Additionally, if initial conditions are in the set A1, then the self-mapping is expansive. The blue lines (set A3) define the boundaries between regions, where the self-mapping is neither expansive nor contractive. The equilibrium points, which are the fixed points of, areand. Figure 2 displays the time evolution of the system when the initial conditions are inand given by. It is observed in Figure 2 how the sequence of iterates enters intoand converges to the equilibrium point (0, 0).

Figure 2.

Evolution of the discrete-time dynamic system (55) and (56), when the initial conditions are .

Fact 5.

(is expansive in): For all, if, then,since, which implies thatand. Therefore,so that;. It can also be concluded thatand;. Additionally,thatand. Thus, one obtains from (60) thatis expansive insince

Fact 6.

(is non-expansive and non-contractive in). For all, if, then,since, which implies that,and. Then,

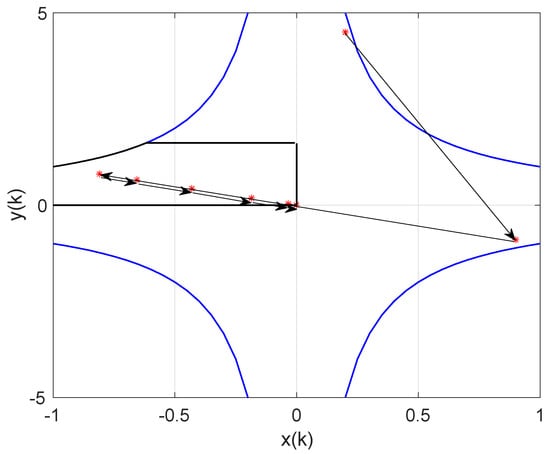

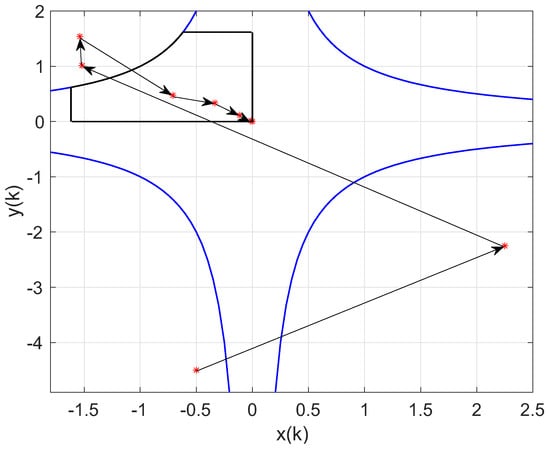

It is also observed that when the image of the self-mapping is included in , the Euclidean distance between two consecutive iterations is bounded and the orbit converges to the origin, as corresponds to a contractive self-mapping, in accordance with Theorem 1. It should be to pointed out here that the distance between two consecutive iterations of the self-mapping is given by the length of the arrow depicted in Figure 2, which corresponds to the Euclidean distance. On the other hand, if initial conditions are in , for instance, the self-mapping is expansive and the orbit diverges, as Figure 3 shows. Figure 3 displays how the length of the arrow increases resulting in an unbounded distance between consecutive iterations. This happens because the value K(i, 1) in Equation (12) from Theorem 1 is unbounded due to the expansive properties of the self-mapping.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the discrete-time dynamics system (55) and (56), when the initial conditions are .

It can also be seen that the image of the self-mapping changes the subset from to and then to , where it remains afterwards. This system can be stabilized in different ways. The clue to stabilizing this system is to include a mechanism in (55) and (56) to force the self-mapping to be cyclic, that is, to include a mechanism to make the self-mapping change its image from A1 to A2 so that any condition from Propositions 1, 2 or 3 is met. For instance, if we force the system to change its image to the set A2 where it remains after a finite number of changes, then the orbit of the system and the distance between two consecutive iterations will both be bounded (Propositions 2 and 3, and their extensions to the general case, Theorems 2 and 3). Two mechanisms are presented in this section for this purpose: a feedback term added to this system and the impulsive control of states. Thus, a feedback term working in the following way is added:

with

If the above feedback term is included in the system, the evolution of (55) and (56) changes to the one depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the discrete-time dynamic system (61)–(63), when the initial conditions are and the feedback gain (63) is employed.

It is observed in Figure 4 that the feedback term acts moving the iteration from the set , where the self-mapping is expansive, to the set , and finally to , where the self-mapping is contractive and where it remains. Consequently, according to Theorem 5, the distance between two consecutive iterations is bounded and converges to zero asymptotically, as seen in Figure 4 by the length of the arrows. Furthermore, this system could also be stabilized by applying an impulsive action to the states so that the controlled system reads:

where the value stands for the value of the state prior to the impulse, while represents the value immediately after the impulse. This case corresponds to the situation when the states of the system suffer an impulsive change whenever they are out of and the iteration is even. This is not the only impulsive action that could stabilize the system, but it is certainly one able to do so. Similarly, the effect of feedback, the impulsive action, causes the self-mapping to become cyclic, changing its image from set A1 to A2. The result of applying this impulsive action is portrayed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the discrete-time dynamics system (64)–(66), when the initial conditions are and the impulsive action (66) is included in the system.

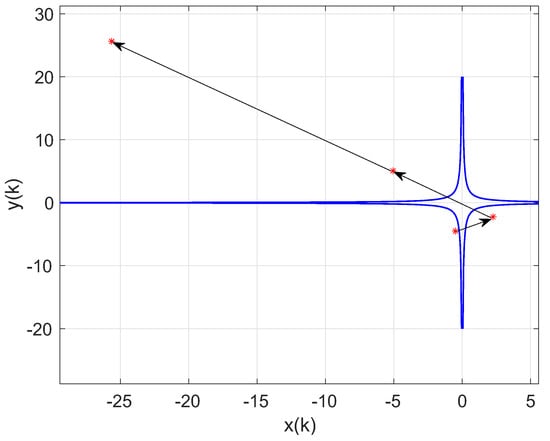

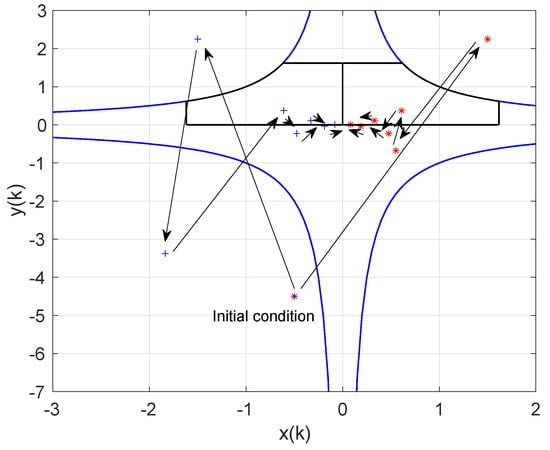

It is observed in Figure 5 how the impulsive action changes the image of the self-mapping and moves it from to and then to until it ends up in , where it remains and the contractivity of the mapping causes the orbit to converge to the origin (0, 0). Since and then the monitored mixed cyclic/acyclic self-mapping T on satisfies , and . It is also observed that the length of the arrows is bounded and converges to zero, as Theorem 5 predicts. Finally, we may consider the multivalued self-mapping given by:

There are two branches in (67), one corresponding to the positive sign for the square root and another corresponding to the negative one. Figure 6 displays the evolution of the two images of the self-mapping when the initial conditions are given by . The positive branch is depicted by asterisks in red, while the negative branch is portrayed with plus symbols.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the multi-valued discrete-time dynamic system (67) and (68), when the initial conditions are . The positive branch is depicted by asterisks in red, while the negative branch is portrayed in blue plus symbols.

As Figure 6 shows, the multivalued mapping diverges and the distance between two successive iterations increases and is not asymptotically bounded. However, if an impulsive action is added to this system as:

Then, the system stabilizes, as Figure 7 depicts:

Figure 7.

Evolution of the multi-valued discrete-time dynamic system (69)–(71), when the initial conditions are and the impulsive action (71) is included in the system. The positive branch is depicted by asterisks in red, while the negative branch is portrayed in blue plus symbols.

The effect of the impulsive action is to force the image of the mapping to move from to , where the mapping is contractive. Under these circumstances, we are in the condition of applying Theorem 5, and the distance between two successive points reduces and the orbit converges to the origin and the stable equilibrium point of the system (0, 0) which is in . There is another fixed point, , which is an unstable equilibrium point.

6. Conclusions

A multivalued self-mapping on the union of a finite number of subsets of a metric space has been considered. Such a mapping might be of a mixed cyclic and acyclic nature being able to perform some iterations within each of the subsets before switching to its right adjacent one when generating orbits. The self-mapping is admitted to be either locally contractive, non-expansive/non-contractive and even locally expansive for different combinations of pairs of adjacent subsets. The properties of asymptotic boundedness of the distances associated with the elements of the orbits are proved under certain conditions of the global dominance of the contractivity for groups of consecutive iterations of the self-mapping, each of those groups of non-necessarily fixed size. If the metric space is a uniformly convex Banach space and the subsets are closed and convex, then some particular results on the convergence of the sequences of iterates to the best proximity points of the adjacent subsets are obtained in the absence of eventual local expansivity for switches between all the pairs of adjacent subsets. An application for the stabilization of a discrete dynamic system subject to impulsive effects in its dynamics due to finite discontinuity jumps in its state is also discussed. For that purpose, the iterations being run by the cyclic/acyclic self-mapping are subject to a monitoring process which is governed by a switching rule between adjacent subsets of the configuration in order to compensate for eventual instability of the solution under different system parameterizations and impulsive controls. Numerical examples were also given and discussed.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, M.D.l.S.; Funding acquisition, M.D.l.S.; Investigation, M.D.l.S. and A.I.; Methodology, M.D.l.S. and A.I.; Project administration, M.D.l.S.; Software, A.I.; Supervision, A.I.; Validation, A.I.; Visualization, A.I.; Writing—original draft, M.D.l.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Basque Government, Grant IT1555-22.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Spanish Government and the European Commission for its support through grant RTI2018-094336-B-I00 (MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE) and to the Basque Government for its support through grants IT1207-19 and IT1555-22. They are also grateful to the referees by their useful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eldred, A.A.; Veeramani, P. Existence and convergence of best proximity points. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2006, 323, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.K.; Lee, K.H. Existence of best proximity pairs and equilibrium pairs. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2006, 316, 433–446, Corrigendum in J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 329, 1482–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olisama, V.; Olareru, J.; Akewe, H. Best proximity point results for some contractive mappings in uniform spaces. Int. J. Anal. 2017, 2017, 16173468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, N.V.; Radenovic, S. Remarks on theorems for cyclic quasi-contractions in uniformly convex Banach spaces. Kragujev. J. Math. 2016, 40, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, N.V.; Hang, V.T.L. Best proximity point theorems for cyclic quasi-contraction maps in uniformly convex Banach spaces. Bull. Aust. Math. Soc. 2017, 95, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini-Harandi, A. Best proximity point theorems for cyclic strongly quasi-contraction mappings. J. Glob. Optim. 2013, 56, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Zhao, X.Y.; Sun, Y.Q. Cyclic quasi-contractions of Ciric type in b-metric spaces. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2017, 10, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fisher, B. Quasi-contractions on metric spaces. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1979, 75, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.; Singh, S.R.; Kumar, S.; Verma, S. On nonunique fixed point theorems via interpolative Chatterjea type Suzuki contraction in quasi-partial b-metric space. J. Math. 2022, 2022, 2347294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastry, K.P.R.; Vali, S.K.; Rao, C.S.; Rahamatulla, M.R. Quasi nonexpansive sequences in dislocated quasi-metric spaces. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2013, 2, 826–833. [Google Scholar]

- Karpagam, S.; Agrawal, S. Best proximity point theorems for p-cyclic Meir-Keeler contractions. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2009, 2009, 197308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpagam, S.; Agrawal, S. Best proximity point theorems for cyclic orbital Meir-Keeler contraction maps. Nonlinear Anal. 2011, 74, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Bati, C.; Suzuki, T.; Vetro, C. Best proximity points for cyclic Meir-Keeler contractions. Nonlinear Anal. 2008, 89, 3790–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Sen, M. On a general contractive condition for cyclic self-mappings. J. Appl. Math. 2011, 2011, 542941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Sen, M.; Agarwal, R.P. Some fixed point-type results for a class of extended cyclic self-mappings with a more general contractive condition. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2011, 2011, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abkar, A.; Gabeleh, M. The existence of best proximity points for multivalued non-self-mappings. Rev. Real Acad. Cienc. Exactas Fís. Naturales. Ser. A Mat. 2013, 107, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, H.; Aslantas, M.; Altun, I. Feng-Liu type approach to best proximity point results for multivalued mappings. J. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2019, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, H.A.; de la Sen, M. A solution of Fredholm integral equation by using the cyclic eta(q)(s)-rational contractive mappings technique in b-metric-like spaces. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslantas, M.; Sahin, H.; Altun, I. Best proximity point theorems for cyclic p-contractions with some consequences and applications. Nonlinear Anal. Model. Control 2021, 265, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, O. A new type of contractive mappings in complete metric spaces. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov. Ser. III Math. Inform. Phys. 2008. preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Kailath, T. Linear Systems; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Delasen, M. A method for improving the adaptation transient using adaptive sampling. Int. J. Control. 1984, 40, 639–665. [Google Scholar]

- Delasen, M. Application of the non-periodic sampling to the identifiability and model matching problems in dynamic systems. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 1983, 140, 367–383. [Google Scholar]

- Ibeas, A.; de la Sen, M. Exponential stability of simultaneously triangularizable switched systems with explicit calculation of a common Lyapunov function. Appl. Math. Lett. 2009, 22, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Sen, M.; Ibeas, A. Stability results for switched linear systems with constant discrete delays. Math. Probl. Eng. 2008, 2008, 543145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Shao, J.H.; Xi, F.B. Stability of regime-switching jump diffusion processes. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2020, 484, 123727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.A.; Liu, S.T. Reachable set estimation for continuous-time impulsive switched nonlinear time-varying system with delay and disturbance. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 420, 126910. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.E.; Xing, X.R. Stabilization of uncertain switched systems with frequent asynchronism via event-triggered dynamic output-feedback control. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, 6509213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.T. Semi-time-dependent stabilization for a class of continuous-time impulsive switched linear systems. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2022, 10, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Shen, X.Y.; Li, X.H. Stability analysis ands synthesis for 2-D switched systems with random disturbance. Mathematics 2022, 10, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghieh, A.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Tavoosi, J.; Mobayen, S.; Rojsiraphisal, T.; Asad, J.H.; Zhilenkov, A. Observer-based control for nonlinear time-delayed asynchronously switching systems: A new LMI approach. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouktonglang, T.; Poochinapan, K.; Yimnet, S. Robust finite-time control of discrete-time switched positive time-varying delay systems with exogenous disturbance and their application. Symmetry 2022, 14, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouktonglang, T.; Yimnet, S. Global exponential stability of both continuous-time and discrete-time switched positive time-varying delay systems with interval uncertainties and all unstable subsystems. J. Funct. Spaces 2022, 2022, 3968850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimnet, S.; Niamsup, P. Finite-time stability and boundedness for linear switched singular positive time-delay systems with finite-time unstable subsystems. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2020, 8, 541–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).