Funds of Identity and Humanizing Research as a Means of Combating Deficit Perspectives of Homelessness in the Middle Grades

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Background

- share the housing of other persons due to financial hardship, also known as “doubled-up”;

- are living in motels, hotels, trailer parks, or camping grounds;

- are living in emergency or transitional shelters;

- are abandoned in hospitals;

- are awaiting foster care placement;

- have a primary nighttime residence that is not designed as regular sleeping accommodation for human beings;

- live in cars, parks, public spaces, abandoned buildings, substandard housing, bus, or train stations, or similar settings;

- or are classified as migratory children who qualify as homeless.

- What funds of identity do students experiencing homelessness possess?

- How are these funds of identity supported, if at all, by school structures and personnel?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Humanizing Research

2.2. Funds of Identity

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Participant Recruitment

3.2. Participant

3.3. Data Sources

[I]dentities or acts of identification can be materialized, encoded, or inscribed into tangible artifacts such as a diagram, a picture, a song, or any written, spoken, visual, or multimedia product. These are identity tools created by learners who invest in them and project onto them their meanings, interests, and so on.[10] (p. 44)

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

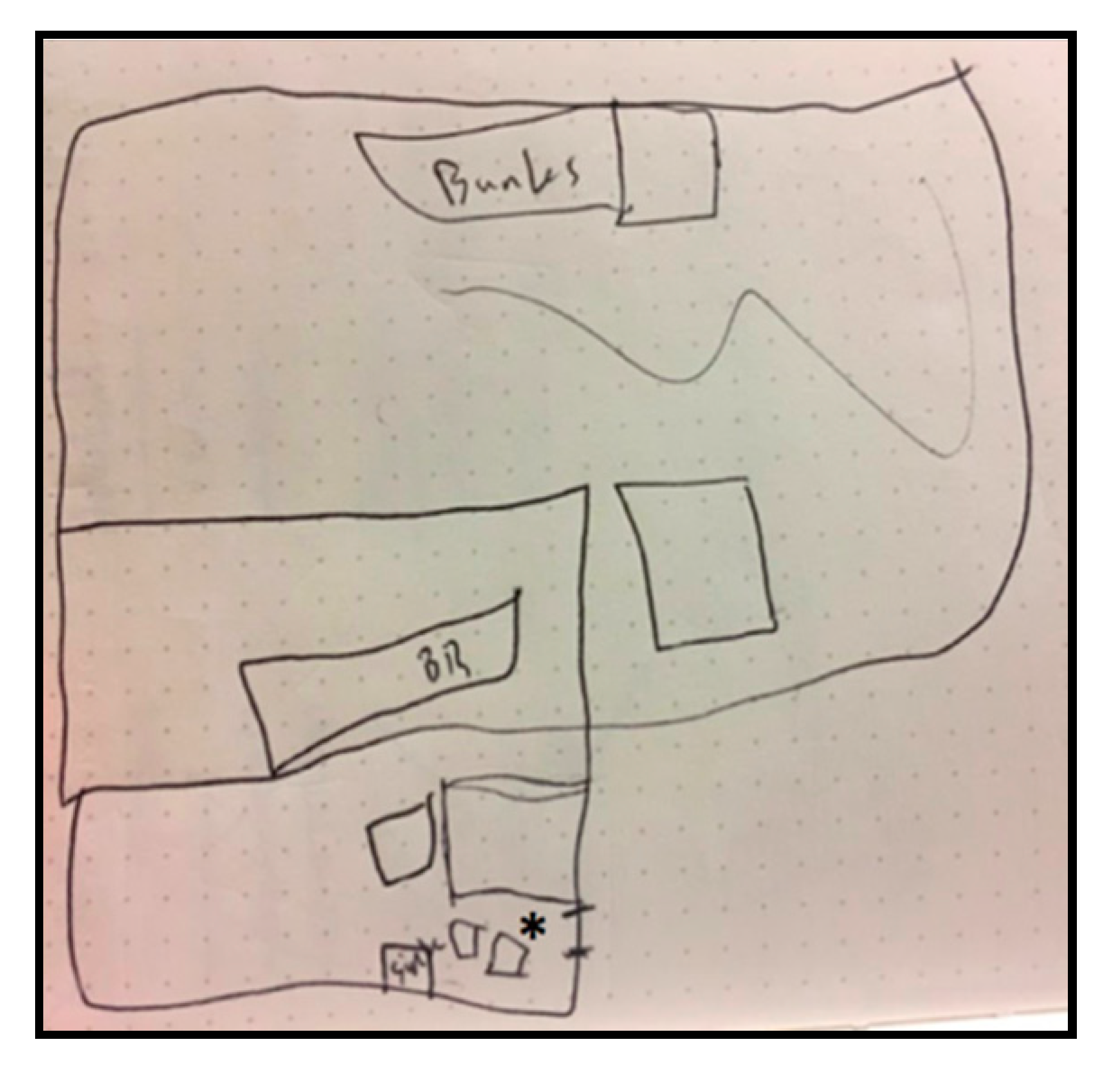

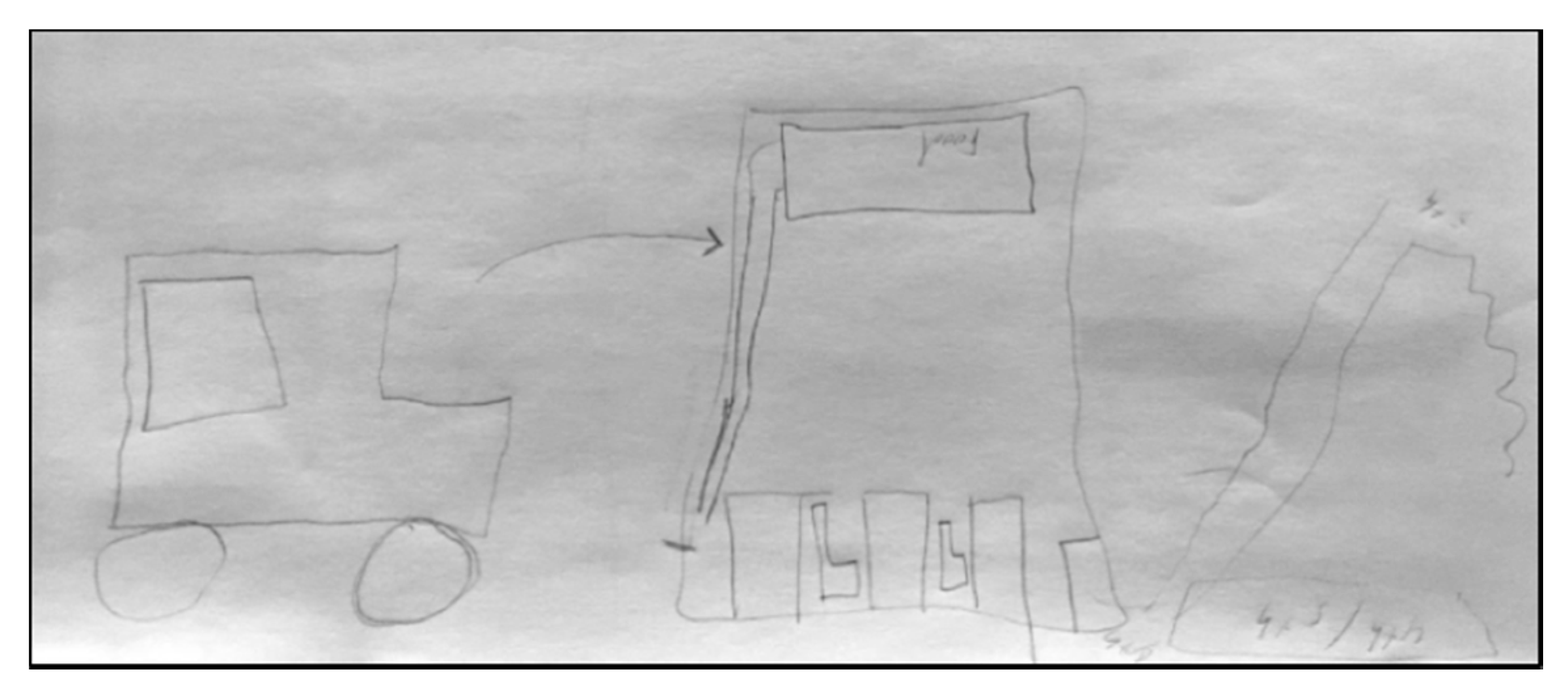

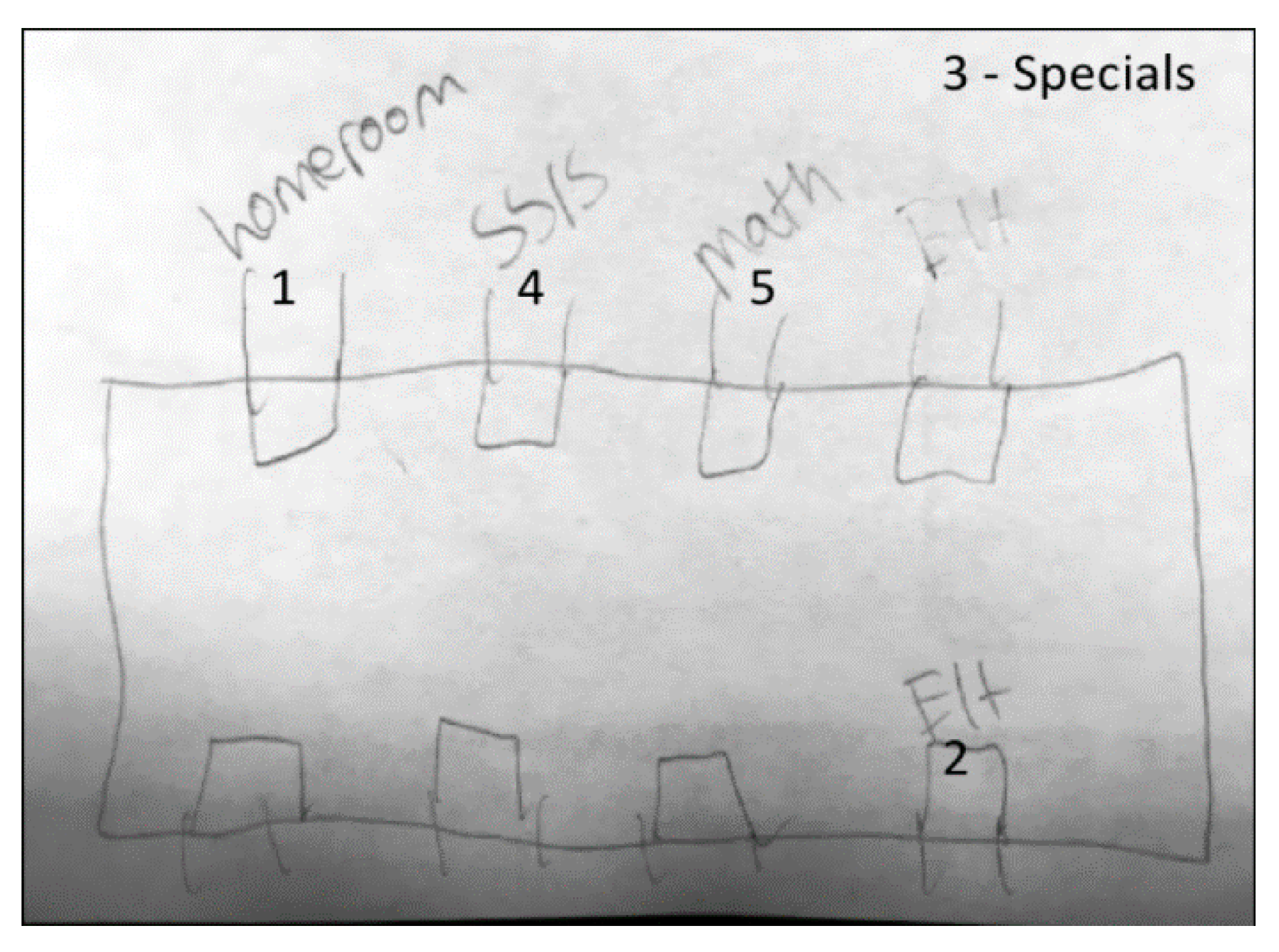

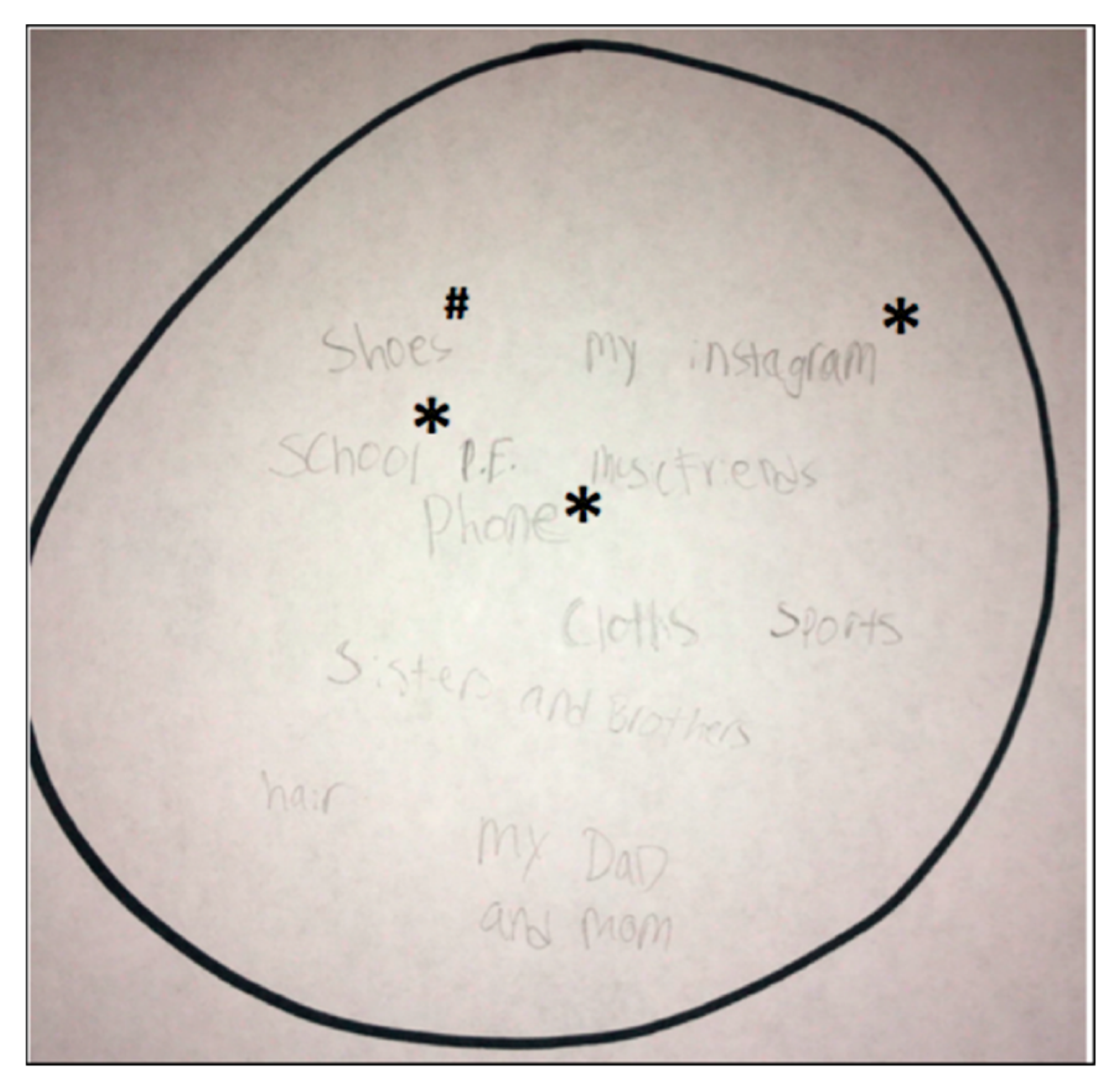

4.1. AJ’s Identity Artifacts

They don’t have Wi-Fi here. No. There’s nothing to do. There’s only one room … you know, that Internet provider store is right in front of the shelter. But there’s one room in front … inside the shelter. And that’s all the rooms that got Wi-Fi. When nobody was in there, like, when nobody lived in that room, I would go in there all the time. And just stayed in there, too. Like, all night. But somebody got that room. Somebody moved in the room, so I can’t go in there no more.

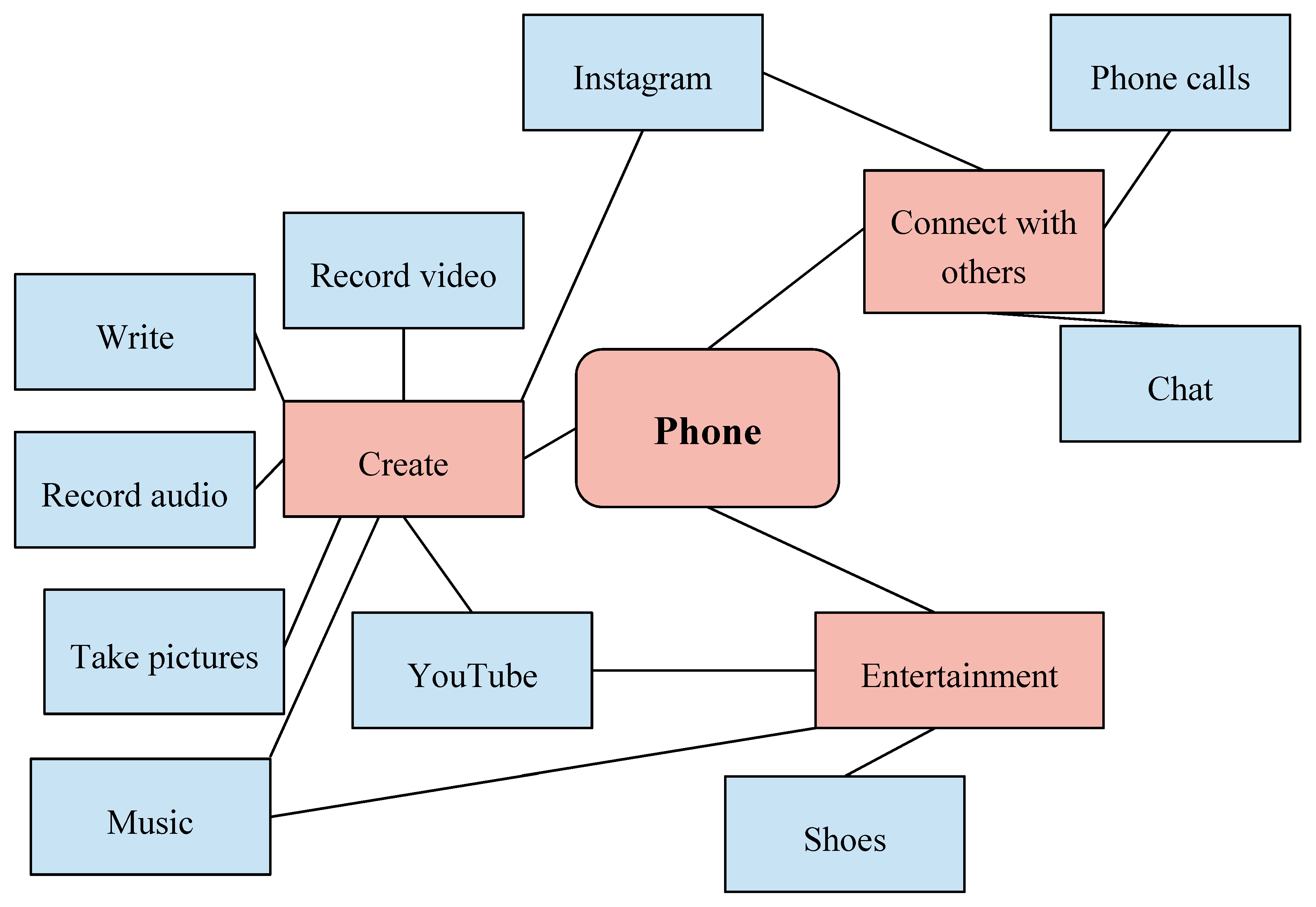

| AJ: | My phone is in the middle. |

| Researcher: | Yeah? |

| AJ: | Mm-hmm (affirmative). |

| R: | The most important? |

| AJ: | Yeah. |

| R: | Everything moves out from the middle? |

| AJ: | Mm-hmm (affirmative). My phone. My Instagram. |

| R: | Yeah. I mean you and I talk about your phone a lot. |

| AJ: | Yeah. |

| R: | Like I imagined your phone was going to be somewhere in the circle. |

| AJ: | While you were just now talking to me, I just like imagined you were a diamond person and I’m telling you how and what my diamond would look like. Like you’re making me a customized chain. |

4.2. AJ’s Identity as a Creator

| AJ: | Guess what? My friend Beth, she go to my school and she in the fifth grade but not in my class. She got 1000 followers. |

| R: | Yeah? You’ll get there. Something tells me you’ll be there soon. |

| AJ: | I know. If I got 1000 followers, I’m gonna end up getting the check mark. You know what that is? |

| R: | Yeah, an official account? |

| AJ: | Yeah, that means you famous. |

- write it using the notes app on his phone,

- rehearse the rap,

- find a good backdrop,

- enlist a family member to hold the phone while recording, and

- find a place that has the Wi-Fi bandwidth to upload a video to YouTube.

I got scared one time. I thought my Instagram got deleted. I thought my aunty did it, because when I was visiting her I was making my little cousin, Cory, an account. And so he said, “Can you put your Gmail for me?” And so I put my Gmail in and so he had an account, but he was signed into my Gmail on it, though. So, my aunty called me and said, “AJ, what’s Cory’s password on his tablet?” And I was like, “I forgot it.” And so she changed it herself, but when she changed his, she ended up changing mine too. I didn’t know the password and I asked her, “You messed up my Instagram. What’s the password?” She didn’t say nothing. She didn’t even respond back. So I had to sign in, get help signing in, and I just signed in on my own. My name, my username. I typed that in and then I could log in. I got scared though.

- Unlike AJ, I have a personal Internet connection and do not need to find strategic places around the city to gain access,

- Unlike AJ, I have a personal phone line that I can use as long as I am in a location that has cell service, and

- Unlike AJ, my connection to stability and familiarity is not dependent upon gaining access to a social media account.

Everybody hates art. Nobody likes art. It’s so boring. It’s just like, we always have to color and junk. They make us color with crayons and markers. Like, boring baby stuff. Like, not even kindergartners like art. Nobody likes art. Everybody walks into art and they’d [shrug and tune out]. Art teacher be sitting there still talking like she don’t care. She would just keep teaching. She think we like art, but we don’t.

4.3. Supports for AJ’s Creator Fund of Identity

Me and all my friends like to play on our phones at recess. It’s kind of like, the teachers will say if you have your phone out or anything, like it’s on you. Because if you get it stolen then … [shrugs] … But at the same time, they don’t really want us on our phones. We can’t do nothing on them, though because there are no hotspots, so we just take pictures and listen to music.

I was bored. Like there was nothing to do, so I just (starts to smile) … Our bus monitor, he’s real old and he talk like … Our bus monitor is old. He like 50-something. And I was just bored or something like … I didn’t have no Wi-Fi. Couldn’t play on my phone and then so I did ask, “Why do you always wear church shoes in school?”

4.4. Interconnectedness of AJ’s Funds of Identity

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Collection Protocols

- Tell me about your experiences in school.

- What are some things that you like about the school?

- What are some things that you would change if you had the opportunity?

- Draw a map of your school

- Label the map with the places that you go (classes, lunch, before/after school, places you hang out, etc.)

- Identify people/places/things on the map that are strengths of your school

- Identify people/places/things on the map that you feel could be improved

- Conversation taking place after creation of map:

- Describe what you included in your map

- What were the strengths you listed?

- What about them makes you consider them strengths?

- What were the things that could be improved?

- What about them makes you think they could be improved?

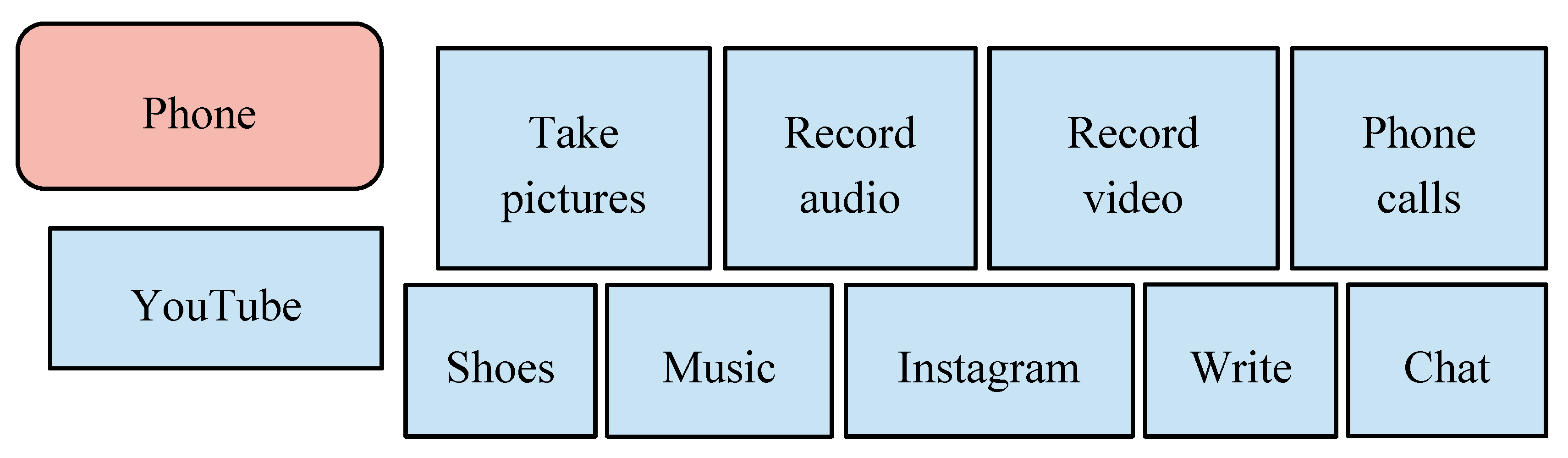

- I would like for you to write down the people, activities, and things that are most meaningful to you in the big circle. Write inside some smaller circles the most significant people and write inside a small square activities, hobbies, or things. I would like for you to think about the center of the circle as being the most important to you. The further something is from the center of the circle the less important it is to you.

- Conversation to take place after the significant circle is created:

- Describe what you included in your significant circle.

References

- National Center for Homeless Education. Education of Homeless Children and Youth (EHCY) Federal Data Summary for School Years 2012–2013 to 2014–2015; National Center for Homeless Education: Greensboro, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United States Federal Government. The McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Assistance Improvements Act of 2001; United States Federal Government: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- United States Department of Education. Supporting the Success of Homeless Children and Youth [Fact Sheet]; United States Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aviles De Bradley, A.M. Unaccompanied homeless youth: Intersections of homelessness, school experiences, and educational policy. Child Youth Serv. 2011, 32, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, K. Promoting and developing direct scribing to capture the narratives of homeless youth in special education. Qual. Soc. Work. 2015, 14, 794–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinegar, K. A content analysis of four peer-reviewed middle grades publications: Are we really paying attention to every young adolescent? Middle Grades Rev. 2015, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- National Middle School Association. This We Believe: Keys to Educating Young Adolescents; National Middle School Association: Westerville, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, D. ‘A friend who understands fully’: Notes on humanizing research in a multiethnic youth community. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2011, 24, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Guitart, M. Towards a multi methodological approach to identification of funds of identity, small stories and master narratives. Narrat. Inq. 2012, 22, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Guitart, M. Funds of Identity: Connecting Meaningful Learning Experiences in and out of School; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 1107147115. [Google Scholar]

- Winn, M.T.; Ubiles, J.R. Worthy Witnessing: Collaborative Research in Urban Classrooms. In Studying Diversity in Teacher Education; Ball, A., Tyson, C., Eds.; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 295–308. ISBN 1442204419. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, D.; Winn, M.T. Humanizing Research: Decolonizing Qualitative Inquiry with Youth and Communities; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 1452225397. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Against the unchallenged discourse of homelessness: Examining the views of early childhood preservice teachers. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2013, 34, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, C. Educating America’s homeless youth through reinforcement of the McKinney Vento Homeless Assistance Act. Faulkner Law Rev. 2015, 6, 395–408. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A.L.; Geller, K.D. Unheard and unseen: How housing insecure African American adolescents experience the education system. Educ. Urban Soc. 2016, 48, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L.C.; Amanti, C.; Neff, D.; Gonzalez, N. Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Pr. 1992, 31, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L.C.; Gonzalez, N. Lessons from the research with language minority children. J. Read. Behav. 1994, 26, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Guitart, M.; Moll, L.C. Funds of identity: A new concept based on the funds of knowledge approach. Cult. Psychol. 2014, 20, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joves, P.; Siques, C.; Esteban-Guitart, M. The incorporation of funds of knowledge and funds of identity of students and their families into educational practice. A case study from Catalonia, Spain. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 49, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Guitart, M.; Moll, L.C. Lived experience, funds of identity and education. Cult. Psychol. 2014, 20, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Federal Government. The Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act; United States Federal Government: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Benson, J.E.; Johnson, M.K. Adolescent family context and adult identity formation. J. Fam. Issues 2009, 30, 1265–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 080395767X. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 0761919716. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, D.; Vélez, V.N. Maps, mapmaking, and critical pedagogy: Exploring GIS and maps as a teaching tool for social change. Seattle J. Soc. Justice 2009, 8, 273–302. [Google Scholar]

- Graue, M.E.; Walsh, D.J. Studying Children in Context: Theories, Methods, and Ethics; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 0803972571. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A. Breaking methodological boundaries? Exploring visual, participatory methods with adults and young children. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 19, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 1506330207. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt, T.A. The SAGE Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 1412909279. [Google Scholar]

- Toolis, E.E.; Hammack, P.L. The lived experience of homeless youth: A narrative approach. Qual. Psychol. 2015, 2, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimpare, S. Ghettos, Tramps, and Welfare Queens: Down and out on the Silver Screen; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 0190660724. [Google Scholar]

- Steinkuhler, C. Cognition and Literacy in Massively Multiplayer Online Games. In Handbook of Research on New Literacies; Coiro, J., Knobel, M., Lankshear, C., Leu, D., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 611–613. ISBN 0805856528. [Google Scholar]

- Kozol, J. Rachel and Her Children: Homeless Families in America; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 0307345890. [Google Scholar]

| Four Essential Attributes An education for young adolescents must be | |

| Developmentally responsive: | using the distinctive nature of young adolescents as the foundation upon which all decisions about school organization, policies, curriculum, instruction, and assessment are made. |

| Challenging: | ensuring that every student learns and every member of the learning community is held to high expectations. |

| Empowering: | providing all students with the knowledge and skills they need to take responsibility for their lives, to address life’s challenges, to function successfully at all levels of society, and to be creators of knowledge. |

| Equitable: | advocating for and ensuring every student’s right to learn and providing appropriately challenging and relevant learning opportunities for every student. |

| 16 Characteristics | |

| Educators value young adolescents and are prepared to teach them. | |

| Students and teachers are engaged in active, purposeful learning. | |

| Curriculum is challenging, exploratory, integrative, and relevant. | |

| Educators use multiple learning and teaching approaches. | |

| Varied and ongoing assessments advance learning as well as measure it. | |

| A shared vision developed by all stakeholders guides every decision. | |

| Leaders are committed to and knowledgeable about this age group, educational research, and best practices. | |

| Leaders demonstrate courage and collaboration. | |

| Ongoing professional development reflects best educational practices. | |

| Organizational structures foster purposeful learning and meaningful relationships. | |

| The school environment is inviting, safe, inclusive, and supportive of all. | |

| Every student’s academic and personal development is guided by an adult advocate. | |

| Comprehensive guidance and support services meet the needs of young adolescents. | |

| Health and wellness are supported in curricula, schoolwide programs, and related policies. | |

| The school actively involves families in the education of their children. | |

| The school includes community and business partners. | |

| Type | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Geographical | Any reference to an area such as a river, a landscape, a mountain, a town, a city, a country, or a nation. | Canadian, Georgian, Athenian, Appalachian |

| Practical | Significant activities for a person such as a sport, music, or work. | Basketball, guitarist, drummer, barista |

| Cultural | Artifacts such as flags or religious symbols. | Star of David, Sikh Khanda, cross |

| Social | Relevant people. | Partner, family members, friends |

| Institutional | Any social institution such as references to marriage or to a specific belief system. | Baptist, Sunni, university student, marriage |

| Friends | Family | Shelter | Apartment | Sports | Food |

| Phone | Music | Rap | Hair | PE | |

| Shoes | Teachers | Schools | Bus | Clothes | Discipline |

| Dad | Cars | Drawing | Art |

| Fund of Identity | Where in the Data This Fund Was Documented |

|---|---|

| Family | Field notes, introductory interview, map of shelter, discussion of school map, significant circle, discussion of significant circle, member check |

| Friends | Field notes, introductory interview, map of school, discussion of school map, significant circle, discussion of significant circle, member check |

| Creator | Field notes, introductory interview, discussion of school map, significant circle, discussion of significant circle, member check |

| Homeless | Field notes, introductory interview, discussion of school map, discussion of significant circle, member check |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moulton, M. Funds of Identity and Humanizing Research as a Means of Combating Deficit Perspectives of Homelessness in the Middle Grades. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040172

Moulton M. Funds of Identity and Humanizing Research as a Means of Combating Deficit Perspectives of Homelessness in the Middle Grades. Education Sciences. 2018; 8(4):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040172

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoulton, Matthew. 2018. "Funds of Identity and Humanizing Research as a Means of Combating Deficit Perspectives of Homelessness in the Middle Grades" Education Sciences 8, no. 4: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040172

APA StyleMoulton, M. (2018). Funds of Identity and Humanizing Research as a Means of Combating Deficit Perspectives of Homelessness in the Middle Grades. Education Sciences, 8(4), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040172