Abstract

In this article the author shall argue that before Namibian independence in 1990, Christianity was used by some as a weapon of breaking down, or as a tool of, colonialism, racism, and apartheid. In the name of a religious god unashamed acts of violence and wars were committed and resulted in genocide of 1904 to 1908. However, such brutalities did not conquer the African spirit of what is identified in this article as the Ubuntu (humaneness). Inspired by their sense of Ubuntu the Africans, in the face of German colonialism and the South African imposed Apartheid system, finally emerged victorious and accepted the model of religious pluralism, diversity, and the principle of African Ubuntu. We shall, furthermore, argue that the Namibian educational system and the Namibian Constitution, Articles 1 and 21, the Republic of Namibia is established as a secular state wherein all persons shall have the right to freedom to practise any religion and to manifest such practice. It means religious diversity and pluralism is a value, a cultural or religious or political ideology, which positively welcomes the encounter of religions. It is often characterized as an attitude of openness in a secular state towards different religions and interreligious dialogue and interfaith programs. As an example we shall focus on the subject of Religious and Moral Education where such religious diversity and pluralism are directly linked to political, social, and economic issues, as well as moral values.

1. Introduction

Over the past one hundred years, Christianity has experienced a profound southern shift in its geographical centre of gravity. In 1893, 80% of those who professed the Christian faith lived in Europe and North America, while by the end of the twentieth century almost 60% lived in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific [1].

In the twentieth century Christianity began as a Western religion, and indeed “the Western religion; it ended the century as a non-Western religion, on track to become progressively more so” [1]. Today, the churches of the global South are more typical representatives of Christianity.

Furthermore, this growth could mean that within thirty to forty years, most Roman Catholics will be Hispanics; the highest percentage of Protestants will be Africans, and “if we wish to visualize a ‘typical’ contemporary Christian, we should think of a woman living in a village in Nigeria or in a Brazilian favela” [2].

Such demographic shifts in Christianity mean that the “centre” of European/North American Christendom has passed. As Andrew Walls points out, “today some of what in 1910 appeared to be ‘fully missionised lands’ are the most obviously the prime mission fields of the world” [3]. Furthermore, the time has passed when Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific sat at the feet of Europe and North America in order to listen and learn about religious and secular issues. Today, all continents must equally contribute towards such debates.

Therefore, let me state that the whole of Africa, especially in light of such drastic demographic shifts from a religious perspectives, may be characterised as a continent with a very strong sense of religiosity and morality. Take as a cue the following African parable on the spiritual, moral, and politico-economic awakening of the continent:

A visitor interrupted me. “Excuse me,” he said. “Could you tell me the way to Africa?” “Easy,” I said. “You’ll recognise Africa from the people. They’ll all be crying.” “That’s funny,” said the man. “When I was a little boy and a refugee there, Africans were smiling. They were full of hope. They had leaders who promised them that if they worked hard and loved one another they would prosper.” As we were coming to Africa, I asked him a question. “By the way,” I remarked, “What is your name?”

“My name is Jesus,” he said. Soon Jesus and I came to a lake in Africa. We sat down, took off our shoes and washed our feet. Jesus’ feet were soon sparkling clean but I couldn’t wash the dirt off mine. The more I washed, the dirtier they got. The dirt ran into the lake and soon the lake was completely covered in green scum and everything started to die. Fish gasped for air, water snakes writhed in agony, and rats lay on the surface, feet up, breathing their last.

Jesus stood up, waved his arms, looked to the sky and shouted, “Long live Africa!” And at that the waters cleared, the fish recovered, and elephants, lions, rhino, springboks, goats, sheep, cattle, dogs, and cats came to the lake to drink. Then Jesus said, “Look, the giant is awakening! It is now your turn to make sure the giant is walking [4].”

Such stories are not merely stories or merely some kind of a wish for a miracle but contain the saying: ora et labora (pray and struggle for justice) [5]. In other words, to pray and struggle for justice means to fully grasps that “prayer holds the word of faith the way the earth holds the seed until it sprouts” [5].

As people from African religions, Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, as well as citizens of this world, we are called upon to pray and to work for socio-politico-economic justice simultaneously by linking orthodoxy (correct teachings or doctrines of our individual religions), orthokardia (right heartedness or spirituality towards the Divine and neighbours), and orthopraxis (transformative social actions). Such direct and intimate linking insists that spirituality or religion must express itself in social actions. In other words, God must not be de-emphasised, faith not be neglected, and praxis not be avoided. In short, religion is social ethics.

Today, to say Namibia is a “secular state” or a “secular society” does not mean that we are not committed to religion. It means that secularism is not the opposite of faith. In contrast, being secular means asking the God-Question and the Human-Question or asking questions about faith and socio-politico-economic affairs of this world. Better expressed, it is a question of what the Bible or Qur’an has to do with daily newspapers. It is about connecting the Holy Scriptures with our daily lives.

In Namibia the essence of African religions, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam has to do with the very essence of God and humanity. It is a comprehensive way of life leading to a balanced way of living out one’s religious beliefs, one’s intellectual abilities, one’s bodily existence, and one’s social ethical behaviours. In other words, among the blessings of secular state are, maybe first and foremost, the freedom of religions and freedom to gather for religious meetings or to allow religious teachings in various contexts as practiced by different faiths in a secular state and most importantly, to promote such principles freely, democratically, as well as being based on the rule of law and justice for all [6].

In this article I focus on three key parts: part one deals on a profile of historical background to Namibia that is situated in the Southern region of Africa. Here I am reflecting on how Africa is the ‘awakening giant’ according to the parable above. This awakening is in itself not new. It is as old as Africa itself. Ever since the era of slave trade followed by colonization, Africa has tried at various levels to reinvent itself with varying degrees of success. There is ample evidence of the resistance put up by our forebears throughout the slavery and the colonial era which bear testimony that Africans have always tried to assert themselves and break loose from bondage by means of their religious convictions and socio-politico-ethical and economic commitments and praxis.

An example in the history of Namibia is the case of one of Namibia’s legendary leaders, Hendrik Witbooi, also known by his African name, !Nanseb/Gâbemab. For him, no matter how brutal colonialism, cultural dominance, racism, and mental slavery was, the colonisers could not touch the soul of him, his African spirituality, and Ubuntu. !Nanseb wrote several letters to the German Governor, Theodor Leitwein. !Nanseb asked Leitwein not to call him a rebel because “God from Heaven has now broken the Treaty” and the time has come for liberation [7]. In short, he regarded himself as a freedom fighter rather than a rebel. Furthermore, he instructed the Keetmanshoop District Commissioner, Karl Schmidt, to stop lecturing him on peace “like a schoolchild” because the peace of which Schmidt was talking serves only the destruction of black Namibians [7] (p. 160).

The prophetic stance of !Nanseb is best expressed in his letter to Pastor Johannes Ollp from the Rhenist Mission Society (RMS) from Germany on 3 January 1890. According to !Nanseb he has been given by God a “mighty task” or a task that is “most difficult, burdensome and grave”, namely to liberate Namibia from German colonialism. The voice of God said to him: “The time is fulfilled. The way is opened. I lay a heavy task on you.” [7] (p. 33).

Both missionaries and settlers were surprised by such utterances. Some of the missionaries considered the theology and politics of !Nanseb as “regression into Jewishness, superstition, delusion, fanaticism and reverie [8].” However, this was not true. What !Nanseb found was that the theological basis of the RMS was wrong. They were associated with German colonialism and rule.

This association was so strong that many mission stations were fitted out as German military bases [9]. In the face of the might of German colonialism and militarism !Nanseb aptly stated that he “received inspiration” for his struggle for freedom from God because “The time is fulfilled.” Such a theology is based on God’s commitment to liberation and transformation, namely that God acts in history. On 21 March 1990, Namibia gained her independence. On that historical moment or kairos, the words of !Nanseb was realised, namely “The time is fulfilled”.

In part two various aspects of the concept of Ubuntu (humaneness) will be addressed. I shall start the discourse from the perspective of the colonised by reflecting on African spirituality and Ubuntu. A major factor today in Africa is the acknowledgement that African spirituality, anthropology, politics, and culture is rich in values which can enhance people’s understanding, application, and contextualisation of their faiths and betterment to their living conditions/praxis.

John Pobee highlighted this centrality of the community in Africa with reference to Descartes’ well-known dictum, Cogito, ergo sum (I think, therefore I am). An African, Pobee maintains, will rather say Cognatus, ergo sum (I belong through blood relations, therefore I am). Such a communal dimension of all human existence in Africa can hardly be over-emphasised [10]. In short, a person with Ubuntu is open and available to others or is affirming of others and does not see the other as an enemy but as an integral part of co-humanity. Harmony, comradeship, friendliness, and community are seen as the great good of all humanity—the summum bonum [11].

In part three the focus is on a model for Religious and Moral Education in the secular state of Namibia. Two case studies will be presented. The first case deals with the issue of rape. Today, violence, murder, and rape deface the humanity of perpetrators and the lives of its victims and survivors. In this connection it is important to talk about our faces. Being in an encounter means to see the human face of the other. This happens when one looks another in the eye, for to see the other thus means directly to let oneself be seen by other people.

The second case will deal with reconciliation. Reconciliation is a religious, human rights, and socio-politico-economic issue which demands a transformation of the entire human situation in all its aspects. Reconciliation is a situation in which the hungry are fed, the sick are healed, and justice is given to all, especially the marginalised and the poor.

2. Part One

A Profile of Historical Background of The Republic of Namibia

Predominantly Christian, Namibia is a large, sparsely populated country on the Atlantic Ocean in Southwestern Africa. It is bordered by Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana and Zimbabwe to the east, and South Africa to the south and southeast. In one of the Namibian indigenous languages, Khoekhoengowab, the word, ≠nâmib (enclosure), describes the country’s encompassment by two deserts: the Kalahari in the east, the Namib in the west and the Atlantic Ocean. Namibia’s total land area is 823,290 square kilometres (317,874 square miles) [12].

With one of the world’s biggest gemstone diamond deposits, large quantities of copper, zinc, uranium, and salt; vast tracts of land ideal for cattle farming; and fish-laden coastal waters, Namibia attracted European settlers beginning in the 1840s. In 1884 the Germans made the territory a colony known as South West Africa and began a sustained drive to subdue the indigenous communities through “protection treaties”, which granted German companies the right to “develop” the area economically. The settlers grew rich, but the indigenous people became impoverished.

Missionaries who arrived with the German colonial regime attempted to Christianize Namibia based upon the strategy of the four Cs: commerce, christianity, civilization, and conquest [13]. One of the German missionaries named Peter Heinrich Brincker, argued in a letter dated 13 March 1889 that such a strategy of the four Cs be applied as follows:

“A matter of applying the language of force in defence of what is right. The country [Namibia] seems to be rich in gold deposits… added to which the land in a moral sense belongs to our native country [Germany], since the Rhenish Mission already has invested thousands of Marks in it; here, you will also find the graves which have been dug for your own fallen missionaries. If any gain is to be made out of this colony, a European power must be based in this country with a military force… to ensure immediate retribution for any likely form of arrogance and insolence.”[14]

Consequently, a military presence was dispatched to Namibia on the 24 June 1889 under the command of a Lieutenant Curt von François [14] (pp. 92–93). The climax of such a history of the four Cs was when in 1904 Kaiser Wilhelm II sent a German commander, General Lothar von Trotha, to crush the liberation struggle in Namibia by “fair means or foul.” [15]

On 2 October 1904, Von Trotha issued the following Vernichtungsbefehl (extermination proclamation) for which he received from Kaiser Wilhelm II, upon his return to Germany in 1905, the Order of Merit for his devotion to the Fatherland. The extermination proclamation read as follows:

I, the great General of the German soldiers, send this letter to the Herero nation. The Hereros are no longer German subjects. They have murdered and robbed, they have cut off the ears and the noses and private parts of the wounded soldiers and they are now too cowardly to fight … The Herero nation must now leave the country. If the people do it not I will compel them with the big tube [artillery]. Within the German frontiers, with or without rifle, with or without cattle [all the Hereros] will be shot. I will not take over any more women or children; I will either drive them back to your people or have them fired on. These are my words to the nation of the Hereros. The great General of the Mighty Kaiser. Von Trotha [14] (pp. 113–114).

The General was true to his word by committing acts of mass destruction. The Otjiherero- and Khoekhoen-speaking Namibians were machine-gunned and their boreholes poisoned, or driven into the desert to die or the few who survived were merely “skin and bone” and on the verge of starvation. Those who survived were taken to the concentration camp known as Shark Island [16].

The German colonial government and its military counterpart referred to this group of people as Kriegsgefangene (prisoners of war). Such prisoners must, therefore, have been regarded as combatants posing a military threat, or were captured in a war situation. However, the so-called Kriegsgefangenen were largely women and children, who were clearly not combatants—and whose confinement in concentration camps was hardly an indispensable safety measure [16].

Instead, the German colonial regime turned these prisoners of war into “a broomstick” because they were so thin that “one could see through their bones” [17]. One of the survivors, Samuel Kariko, vividly described his experience as follows:

“I was sent down with others to an island far in the south, Lüderitzbucht. There on the island were thousands of Herero and Hottentot prisoners. We had to live there. Men, women and children were all huddled together. We had no proper clothing, no blankets, and the night air on the sea was bitterly cold. The wet sea fogs drenched us and made our teeth chatter. The people died there like flies that had been poisoned … The little children died first, and then women and the weaker men … We begged and prayed and appealed for leave to go back to our own homes, which is warmer, but the Germans refused [17].”

Furthermore, when German military power imposed its will on Namibia at gunpoint, the Rhenish Mission Society (RMS) from Germany issued a pastoral letter that justified German colonial militarism and genocide. The Namibian Christians, they claimed, had “raised the sword” against the German colonial rule “which God [had] placed over” them and, therefore, “whoever [took] the sword [would] also perish by the sword”. Thus, the vicious cycle of the four Cs continued to be implemented in Namibia [14] (p. 118).

Put differently, the Europeans introduced Christianity and colonialism to promote the doctrine of having “a place in the sun” [18]. The main tenet of this line of doctrine is based on a Western Weltanschauung that was a combination of Darwinism and pan-Europeanism, namely the uncritical acceptance of the notion of nation (Volk) belonging to the “strongest”, the “most highly developed”, and suggesting that the “underdeveloped” people needed colonial protection and, therefore, could be subjected to mental slavery and cultural dominance [14] (p. 80).

According to George Steinmetz, the western driven religious discourse of the 19th century unfortunately had no positive appreciation of African religion and culture because “there were no footholds for carving out opposing ethnographic stances” or religious-moral discourses [8]. For example, the discourse of the colonisers is expressed by Jean and John Comaroff as follows: “This culture, the culture of European capitalism…had, and continues to have, enormous historical force, a force at once ideological and economic, semantic and social [19].”

To put it differently, western Christianity was responsible not merely for the glorification of European civilisation but also for various attempts to conquer the African mind. However, such a culture constructed according to the four Cs has proven to be unsuccessful because Africans were conscious about the four Cs and refused to be domesticated and colonized. Let me explicate.

3. Part Two

African Spirituality and Ubuntu

At the outset let me start with the words from the Redemption Song by Bob Marley:

“Old pirates, yes, they rob I;

Sold I to the merchant ships,

Minutes after they took I

From the bottomless pit.

But my hand was made strong

By the hand of the Almighty…

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery;

None but ourselves can free our minds.”

When the missionaries and colonialists came the discourse of those who were colonialized started. It started when the colonial powers gave the Bible to Africans while taking the land. Based upon the strategy of the four Cs, they thought that the story would end there.

However, Africans were conscious of the colonisation strategy and started to employ their own discourse based on African spirituality and the principles of Ubuntu. They sang loudly, praised God, closed their eyes in prayer, and listened diligently to the Word of God. At the same time their ears and eyes were wide open to contextualising the gospel and their hands and feet were ready for liberative action [20]. Differently expressed, in contrast to some Christian views which separate spirituality from earthly concerns, African spirituality fully embraces the phenomenal world and enters passionately into its affairs [11].

Such contextualising of the Bible, for example in Southern Africa, resulted in major paradigm shifts. The defining moments were reached when in 1990 and 1994 Namibia became independent and South Africa became democratic after the abolishment of apartheid, respectively.

Let me briefly highlight one of the impacts of such consciousness of the four Cs and the contextualisation of the Bible. On that historic day, on 21 June 1971, the news reached the United Evangelical Lutheran Seminary in Namibia, also known as Paulinum, via short-wave radio, broadcast by the British Broadcasting Corporation, that the International Court of Justice, declared that South Africa’s continued occupation of Namibia was in fact illegal. The announcement surprised some and electrified others, such as the students and lecturers at Paulinum. They were “in heaven” because of the good news and it had an immediate impact on them.

Some of the students and lecturers gathered after a thanksgiving service to discuss further courses of action. After acts of protests and defiance, singing and prayers, without delay, nine students, namely Paul John Isaak, Henog Kamho, Jakobus Ngapurue, Engelhard !Noabeb, Hiskia Uanivi, Hellao Hellao, Set Son Shivute, Jesaja Wahengo, and Paulus Musheko met with two of their lecturers, Dr Johannes Lukas de Vries and Pastor Rudolf Wessler, and drafted the Open Letter of 1971.

They decided that the draft Open Letter be sent to the two black Lutheran Churches, namely the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (ELCIN) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Republic of Namibia (ELCRN) with the plea for further action upon it. The Church Boards of the two Lutheran Churches chose to adopt the students’ letter as their own and issued it with the signatures of Moderator Paulus //Gowaseb of the ELCRN and Bishop Leonard Auala of the ELCIN.

The Open Letter was a document issued at an appropriate time to tell the truth that the birth of the independence of Namibia was at hand. It addressed the basic theological and ethical truths on the struggle for liberation, justice, peace, forgiveness and to build a reconciled and healed nation [21]. The Open Letter of 1971 started the process of conscientization of the Namibian people and offered a window of opportunity to the religious and political bodies to play a major role in the liberation of Namibia, as well as making a decisive contribution which, in the end, culminated in the UN supervised elections in Namibia in 1989. To put it slightly differently, the country gained its independence on 21 March 1990 [6].

Finally, the significance of the Open Letter of 1971 is that in the secular state of Namibia religious and political organisations publicly promoted and reconnected orthodoxy and orthopraxis. Such linkages or reconnections of religion, morality, politics, and human rights are always worthy. To put it boldly: religion is social ethics. We shall now specifically focus on this aspect.

4. Part Three

4.1. Namibian Model for Religious and Moral Education

The subject, Religious and Moral Education (RME), that is taught at all Namibian public primary and secondary schools, appears for the first time after the Namibian independence in 1990. Before Namibian independence, the subject was known as Biblical Instruction or Bible Studies.

Unfortunately, there are still today some minority voices from some Christian leaders who prefer Biblical Instruction in government (public) schools instead of Religious and Moral Education. For example, according to a Namibian newspaper one of the Islamic leaders in Namibia, Armas Malik Shikongo, reported that in April 2018 a group of Christian leaders visiting the State House requested President Hage Geingob to help reintroduce Bible studies in schools as a means to combat immorality.

Shikongo himself, however, is of the view that the current government policy must be maintained since Namibia is a constitutionally secular state and is legally expected to be religiously impartial. Furthermore, public schools are funded by all taxpayers of all religious affiliations and it would, thus, not be fair to introduce in schools teachings of one faith only [22]. In my opinion the view of Shikongo is accepted by the majority of Namibians since the Religious and Moral Education syllabus contributes to the welfare of all Namibians, religiously and politically. Let me explicate.

With the new syllabus of RME in Namibia the learner is given the opportunity to listen to various perspectives of religion and their values on certain moral issues. The main function of this new approach is to give the individual learner the chance to get in touch with his/her own values, to bring them up to the surface and to reflect on them. The learner thereby becomes more sensitive to other people’s needs as well as his/her own, and can anticipate the consequences of actions and develop a greater overall social awareness [23].

A case in point is the contemporary Namibian situation in the schools. It seems that such schools are experiencing moral decay. For example, in one of the Namibian influential newspapers, The New Era, dated 17 March 2017, reported the following:

“Learners’ failure to behave and work in a controlled way by obeying school rules remains a major concern for many schools. Teachers, instead of focusing on teaching, spend most of their time dealing with disciplinary issues, as learners deliberately disrupt classes, often making the class environment less conducive for learning and teaching to take place. Teachers spend more time disciplining learners than teaching.”[24]

Instead, morals ought to guide schools and society in doing what is right and good for both their own benefit and that of the entire nation. It is the morals which have produced the virtues that a society or nation appreciates and endeavours to preserve, such as patriotism, friendship, compassion, love, honesty, justice, freedom, courage, self-control and bravery.

On the other hand, morals sharpen people’s dislike and avoidance of vices like stealing, cheating, treachery, selfishness, dishonesty, and greed. Morals keep society from disintegration. Even if all the ideals embedded in morals are not always achieved, they nevertheless challenge people to aspire to them. They give a sense of harmony, peace, and justice. Such morality is obviously superior to the tyranny of the strong over the weak and stands in direct confrontation with any form of oppression.

Therefore, it is clear that RME is an important subject at school and that the teacher needs to make sure that his/her learners learn and benefit from this subject to make life acceptable and understandable to them.

To promote such a religious and moral basis in the educational levels of the secular state of Namibia the aims of the RME are:

- ➢

- To train learners in a holistic and comprehensive way in order to equip them to present imaginative courses in Religious and Moral Education within a multi-cultural or multi-faith setting and in a life-related and stimulating way.

- ➢

- To help the learners to understand and appreciate the presence of the Divine, as revealed in personal experience, in African religious and cultural heritages, and in the religious teachings and practices as well as in the moral traditions and their applications to all aspects of daily living.

- ➢

- To help the learners to discover for themselves, as individuals in society, each in his/her own way and relating to his/her own moral tradition, the importance of spirituality and morality as vital sources of living and decision-making.

- ➢

- To present to the learners relevant “texts” or stories, and issues or examples from Christian and other religious and secular worldviews and moral traditions, to stimulate their moral consciousness and conscience.

- ➢

- To confront the learners with moral issues and decision-making relevant to their stage of development and living-world; to exercise the self-application of their moral principles within their own life-setting; and to help them integrate these principles as an inherent part of personal and inter-personal development of character, and

- ➢

- To illustrate and strengthen the cohesive power, which shared values, could foster within a society, which seeks unity and understanding among people from different traditions and communities. In short, the approach to teaching Religious and Moral Education has to be child-centred, experiential, contextual, and concentrate on moral values [23].

Furthermore, the following rationale for teaching RME in Namibia was developed:

- ❖

- It gives the learner the opportunity to critically and constructively reflect on the functions of religion and morality in his/her personal life as well as in society.

- ❖

- RME should not replace religious and moral instruction learned at home or in the church, but it should stimulate the learner’s awareness of the various sources of spiritual and moral life.

- ❖

- It also facilitates the individual growth of the learner towards responsible behaviour, tolerance, acceptance of the highest common values of humanity and the discovery of cohesive power of shared values.

- ❖

- Another reason why RME should be offered in schools is that religion functions universally as an important and powerful factor. Responsible ethical conduct is based on religion, secular ideologies, and various value systems. People behave according to their value horizons, which are shaped by their religions and their ideological beliefs.

- ❖

- The purpose of RME is not conversion but it should be religious and life-related. RME is also not the study of doctrinal truths, but it teaches about what people believe about the purpose of their lives and how they should decide what to do.

- ❖

- In order to facilitate an integration of RME to different faculties it should also be linked to other disciplines in the curriculum or such an approach may be viewed as values across the curriculum. This approach is one most teachers readily accept and support. In addition to religious education, which has a moral dimension through the study of other world religions and the examination of current moral and social issues, like war, racism, and animal rights, subjects like history, geography, social studies, and science also have a moral dimension. History offers the opportunity to examine human motives and intentions, whereas geography and social science offer the opportunity to illustrate differences in culture and life styles. Also scientific discoveries and technological development can and do raise serious moral problems. Atomic physics or genetic engineering cannot be taught without the moral issues concerning them. This underlines the fact that most teachers in most subjects are actually involved in moral education based on values that are set by religion [23].

In practice the following methodologies are employed [23]:

4.2. Situation 1: The Lecture Discussion

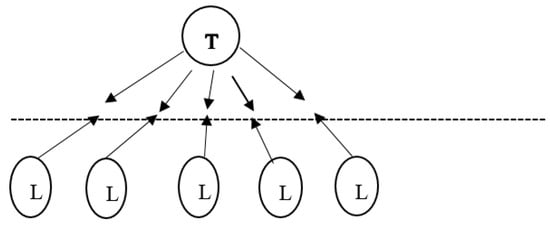

The principle of interaction underlying the lecture discussion is illustrated in this example. Although only five learners are represented in the diagram, the figure may vary, with perhaps 30 learners being a more representative number in this type of situation.

The interaction pattern here is not wholly dominated by the teacher. The arrowheads in the diagram indicate more or less continuous verbal interaction between teacher and leaners. Although as a leader, the teacher asks questions and receives and gives answers, the initiative need not always be his/hers; and competition may develop amongst the learners. The broken horizontal line indicates that there is no sharp distinction between the teacher and learners (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lecture-oriented teaching and discussions.

4.3. Situation 2: Active Learning

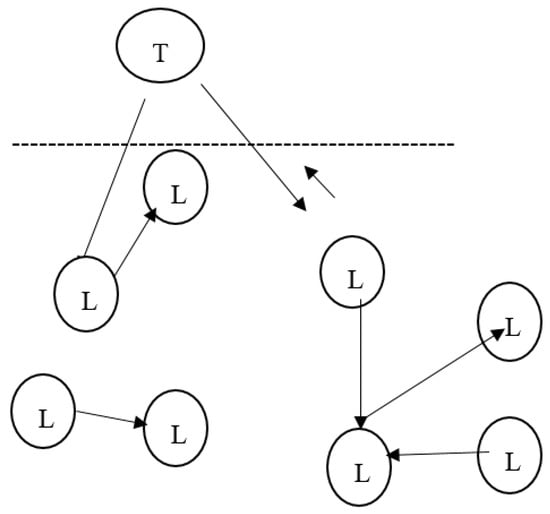

This example depicts a social situation in which the teacher allows discussion and mutual help between learners. Practical work would be an occasion for implementing this type of situation. The letters “TF” in the diagram indicate that the teacher now begins to assume the additional role of facilitator. The situation may be described as task- and learner-centred, and as one beginning to show a cooperative structure (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Task-and Learner-Centred Teaching.

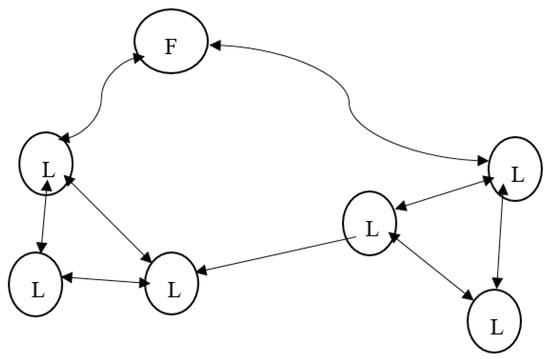

4.4. Situation 3: Active Learning; Independent Planning

Scrutiny of example 3 shows how this third situation evolves logically from the preceding one. The learners are now active in small groups, and the teacher acts more or less exclusively as a facilitator (indicated in the diagram by means of a wavy line) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Active Participatory Teaching Method.

Groups map out their work, adapt to each other’s pace, discuss their difficulties, and agree on solutions. There is independent exploration, active learning, and a maximal development of task-directed leadership in each group. The social climate is cooperative, and the situation may be described as learner- and task-centred.

In summary, there is a progressive change from teacher-centred through task-centred to learner-centred activities, from passive to active learning, and from minimal to maximal participation, thus including learners’ different life orientations. The three situations outlined above will help the teacher and learners not only to understand classroom-based social and learning situations, but also patterns of interaction occurring outside the classroom.

Now I am in the position to present the following two case studies from the perspective of Religious and Moral Education and how such complex topics may be addressed.

4.5. Case Study One: Violation of the Human Body

A mother and her two-year old daughter are sleeping in their house at Khorixas, Namibia. Two men, Samuel Uiseb (33-years) and Johannes Rico Goseb (22-years) enter the house. They are intent on violence or, more specifically, to come and invade that very territory of the victims with their penises. The two apparently non-resistant prospective victims are sleeping. They ignored the sleeping mother and abduct the baby, who is later found raped and murdered about 100 metres away. Why such brutality? Note: This story was reported in The Namibian, 17 March 2004.

The above event took place in Namibia in 2004. Immediately two reactions followed this tragic event. First, the female parliamentarians expressed disgust and dismay and demanded that the two men accused of raping and killing a two-year-old girl at Khorixas be sent to jail for life, if found guilty. On the other hand, many women insisted that such cases should not be feminised or made a “woman” thing; instead all parliamentarians, women and men, should go out into their constituencies and do some educating and mobilising around violence against women and children, including rape.

They argued that one should not try to salve our consciences by putting away such people for life in jails. That will be merely an act of treating the symptoms rather than the causes of the scourge of rape. Once again, how should the Namibian society act in the face of violating individual, family, and communal bodies?

At the outset let me state that the views expressed above do not contradict each other. Rather, these views are two sides of the same coin. The starting point in the restoration of moral values in the Namibian society is to campaign or preach the message that recognised the humanity of the other; the message of restoration of moral values by advocating to be a compassionate and caring society, especially towards women and children, while advocating that criminals, if found guilty after a fair trial, be sent to jail for a very long, if not life imprisonment. Let me explicate.

Once a woman was asked by a journalist to define words such as violence and rape. She answered that the term ‘definition’ contains the Latin term ‘finis’, i.e., ‘borderline’, ‘demarcation’, or ‘end’. The very character of violence or rape lies in ignoring the borderlines of an individual, a family or a communal body. Furthermore, she said, when it comes to violence or rape, there is no borderline, and there is no end; violence or rape by its nature respects no border. You may think that your body is the outer borderline of who you are, but a would-be rapist will come and invade that very territory of yours with his penis. When such things happen in any society, she said, such a society needs re-viewing of their humanity and restoration of their moral values [25].

Today, the prevalence of violence, rape, and murder means that such acts negate and refuse to see the Imago Dei (the face of God) in other people. Any society that has problems with a vision of a peaceful living together has lost its conviction that every human being must be treated humanely. According to the Swiss Roman Catholic theologian Hans Küng “every human being without distinction of age, sex, race, skin colour, physical or mental ability, language, religion, political view, or national or social origin possesses an inalienable and untouchable dignity” [26]. In other words, as most African scholars agree, humanity is to be conceived as being in relation.

Today, violence, murder, and rape deface the humanity of perpetrators and the lives of its victims and survivors. In this connection it is important to talk about the faces of us. Being in an encounter means to see the human face of the other. This happens when one looks another in the eye, for “to see the other thus means directly to let oneself be seen by him/her”. It is only when “we move out of ourselves, not refusing to know others or being afraid to be known by them, that our existence is human” according to the Swiss Protestant theologian Karl Barth [27].

4.6. Case Study Two: Reconciliation

At the outset let me start with an imaginative Namibian parable on reconciliation:

There was a man who owned a large farm. He maltreated his farm workers.

They worked for months without getting salaries.

If one of his sheep went missing, the shepherd was faced with two alternatives:

To sleep in the bush or to face a beating.

Without telling the workers, the owner sold the farm.

The government, which had bought the farm, gave it to the same workers and put one of them in charge of it.

After some years, the former owner of the farm returned.

Having wasted all his money. He asked for a place to stay, and for a job…

Jesus asked: What do you think the leader did to his former oppressor?

Before his hearers could answer, Jesus said:

He treated his former boss just as one of the other people on the farm.

He gave him a place and put him to work [28].

It is important that in this Namibian narrative the former boss and the former farm worker reconciled. However, what does reconciliation really entail?

Perhaps we should ask assistance from various Namibian languages. There are three words in Oshiwambo that deal with the concept of reconciliation ediminafanepo (you forgive someone and he/she in turn forgives you), ehanganifo (someone takes the hand of one person, and then takes the hand of another person, thus bringing them together); and etambulafano (two people accept one another following a quarrel; acceptance takes place on an equal footing).

In Khoekhoengowab there are many words for the concept of reconciliation. The focus falls on the prefix re-, which means “again”. These words convey the sense that something which has been destroyed should be rebuilt. Peace which has been destroyed should be re-established, or a relationship should be renewed. The words are //kawa-/haos or //kawa-/hû. The underlying notion is that of beginning anew, unconditionally.

In Otjiherero the word okuhangana means “peace”, or “being together again, being one”. Okuisirisana means “to forgive one another”. Again, reconciliation points to peace, unity, and the re-establishment of a relationship. The Tswana word for reconciliation is kagisano. This means “to live together in peace after a quarrel or a dispute”. The verb agisanang means “to reconcile”. After an issue has been settled, the parties should see to it that peace is maintained. Therefore, reconciliation has the sense of living or staying together, maintaining peace, or giving someone a chance.

In Afrikaans, the word for reconciliation is versoening. The verb is versoen, from which one draws both the verb and the noun soen (“to kiss”). Those who have a relationship close enough for them to be kissing (embracing) are assumed to have been reconciled.

Thus, in most of the indigenous languages of the secular state of Namibia there is the idea of living together in peace, of coming together, of joining hands and having peace, whatever the case may be. The final concept conveyed is that something new should have been established, so as to live together in peace and harmony. However, what is reconciliation and is it really possible to both forgive and forget? Should we always be tempted in the heat of discussions about past historical events and to bring up the past sins of colonialism and apartheid?

Like many other countries emerging from periods of violence, genocide, oppression, colonialism, apartheid and liberation struggle, we inherited two legacies: On one hand the visible effects of the past: the killed, the tortured at Shark Island, Robben Island, and Lubango, the landless, and the poor. On the other side there are the invisible effects: during the era of colonialism, apartheid, and liberation struggle many people “disappeared” without any trace. Today their mothers and fathers and family members are mourning and wishing to bury their dead or disappeared sons and daughters. Yet this basic right of a human being to have a proper funeral and to see the face of the deceased before the burial was denied [28].

As an illustration take the following story told by a mother:

“I was told that my son was killed a few kilometres from Oshakati [by the racist South African regime soldiers]. He was brought home wrapped in a thick, sealed plastic bag. The instruction was that the plastic bag should not be opened…I accepted this as military law. You are not allowed to have the glimpse of your own child—even as he lay there, lifeless. On the day of Wallace’s funeral, his coffin was not opened. It is ten years since I last laid my eyes on my child—nine years since he was laid to rest. But in these nine years, I have been struggling to complete the process of mourning for Wallace.”[29]

When hearing and seeing the visible and invisible effects of violence, war, genocide, colonialism, and apartheid what should we do today? In a similar situation a leading Dutch Reformed Church theologian, Willie Jonker, made an eloquent plea for forgiveness to his black fellow South African Christians on behalf of Afrikaners. Archbishop Desmond Tutu accepted the plea for forgiveness because “enemies are potential allies, friends, colleagues, and collaborators” [29].

Finally, in relation to the furtherance of human rights and their implementation, and in adherence to the policy of national reconciliation, in the secular state of Namibia religious communities are not being given a heavy burden to bear. Instead, religious communities are being issued with an invitation to enter into dialogue with society and the government so that we can all co-operate in the process to ensure all persons enjoy basic human rights, freedom, justice, and reconciliation. Thus, the irreconcilable can be reconciled and the unhealable can be healed.

5. Conclusions

At the beginning of the 21st century, from religious and secular perspectives, we are facing a challenge: as people from African religions, Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, as well as citizens of this world, we are called upon to pray and to work for socio-politico-economic justice simultaneously by linking orthodoxy (correct teachings or doctrines of our individual religions), orthokardia (right heartedness or spirituality towards the Divine and our neighbours), and orthopraxis (transformative social actions).

Differently expressed it means that a “secular state” or a “secular society” from a Namibian perspective does not mean that we are not committed to religion. It means that secularism is not the opposite of faith. In contrast, being secular means asking the God-Question and the Human-Question or asking questions about faith and socio-politico-economic affairs of this world. Better expressed, it is a question of what the Bible or Qur’an has to do with daily newspapers. It is about connecting the Holy Scriptures with our daily lives.

As an example I discussed the case of one of the Namibian’s legendary leaders, Hendrik Witbooi. For him, no matter how brutal colonialism, cultural dominance, racism, and mental slavery was, the colonisers could not touch the soul of him, his African spirituality, and Ubuntu. Such spirit of Ubuntu and African spirituality is self-evident today in Namibian society. Today, religious communities are being issued with an invitation to enter into dialogue with society and the government so that we can all co-operate in the process to ensure all persons enjoy basic human rights, freedom, justice, and reconciliation. Thus, the irreconcilable can be reconciled and the unhealable can be healed.

Therefore, we need to teach the basics of love and care for one another: we need to insist on honesty and compassion, upon sharing and taking responsibility for our own lives in order to again find the sweetness of human kindness in our communities and nation. The task is extremely urgent and we have to make our small steps forward in order to achieve great results.

In short, we are in the process to plant the smallest of all seeds as it relates to our sacred and secular world. Such a task has been well expressed by Steve Biko, during the time of Apartheid and the struggle for racial harmony and democracy. He said that the greatest gift that Africans shall bestow on the rest of our secular and religious world is the greatest possible gift: a more human face.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Stephen Bevans & Roger Schroeder. Constants in Context: A Theology of Mission for Today; Orbis Books: Maryknoll, NY, USA, 2004; p. 242. [Google Scholar]

- Ana, J.D. (Ed.) Religions Today: Their Challenges to the Ecumenical Movement; World Council of Churches: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; pp. IX–X. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, K.R. Edinburgh 1910—Its Place in History. Available online: http://www.towards2010.org.uk (accessed on 5 April 2018).

- Isaak, P.J. The Story of the Rich Christians and Poor Lazarus: Christianity, Poverty and Wealth in the 21st Century. J. Relig. Theol. Namibia 2000, 2, 72–94. [Google Scholar]

- Boff, C. Feet on the Ground Theology. In A Brazilian Journey; Orbis Books: Maryknoll, NY, USA, 1987; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Namibian Constitution; Article 1; Ministry of Urban and Rural Development: Windhoek, Namibia, 2002.

- Heywood, A.; Maasdorp, E., Translators; The Hendrik Witbooi Papers; John Meinert Press: Windhoek, Namibia, 1990; pp. 33, 157–160.

- Steinmetz, G. The Devil’s Handwriting: Precolonial Discourse, Ethnographic Acuity and Cross-Identification in German Colonialism. Soc. Comp. Study Soc. Hist. 2003, 45, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L. Mission and Colonialism in Namibia; Rivon Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 1978; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Pobee, J. Theology by the People: Reflections of Doing Theology in Community; World Council of Churches: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Isaak, P.J. The Influences of Missionary Work in Namibia; Macmillan Publishers: Windhoek, Namibia, 2007; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Isaak, P.J. Governments of the World. Available online: http://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/namibia (accessed on 5 April 2018).

- Isaak, P.J. Cultural Dominance and Mental Slavery: The Role of German and African missionaries in Colonial Namibia. In The German Protestant Church in Colonial Southern Africa: The Impact of Overseas Work from the Beginnings until the 1920s; Lessing, H., Bester, J., Eds.; Cluster Publications: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2012; pp. 578–579. [Google Scholar]

- Hellberg, C. Mission, Colonialism, and Liberation: The Lutheran Church in Namibia 1840–1966; New Namibian Books: Windhoek, Namibia, 1997; pp. 80, 92–93, 113–114, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham, T. The Scramble for Africa 1876–1912; Random House: London, UK, 1990; p. 609. [Google Scholar]

- Drechsler, H. Let Us Die Fighting; Zed Press: London, UK, 1980; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Silvester, J.; Gewald, J. Words Cannot Be Found: German Colonial Rule in Namibia: An Annotated Reprint of the 1918 Blue Book; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, D. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission; Orbis Books: Maryknoll, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 181–189, 262–345. [Google Scholar]

- Jean; Comaroff, J. Of Revelation and Revolution. In Christianity, Colonialism, and Consciousness in South Africa; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; Volume 1, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Isaak, P.J. Towards Black African Theology. Master’s Thesis, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Isaak, P.J. The Lutheran Churches’ Open Letter of 1971: The Prophetic Voice of Church. In The Story of the Paulinum Seminary in Namibia; Namibia Publishing House: Windhoek, Namibia, 2013; pp. 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Islamic Leader Hits Out at Bible Studies Proponents. Available online: https://neweralive.na/posts/islamic-leader-hits-out-at-bible-studies-proponents (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Isaak, P.J. Religious and Moral Education: Grades 8–10; Out of Africa Printers: Windhoek, Namibia, 1997; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ill-Discipline Rife at //Kharas Schools. Available online: https://www.newera.com.na/2017/03/17/ill-discipline-rife-at-kharas-schools/ (accessed on 5 April 2018).

- Fröchtling, D. Violating individual, family and communal bodies: On blindness and relationships reviewed. In Echoes: Justice, Peace and Creation News; World Council of Churches: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Volume 22, pp. 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Küng, H. A Global Ethic: The Declaration of the Parliament of the World’s Religions; The Continuum Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1993; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, K. Church Dogmatics; T&T Clark: Edinburgh, UK, 1957; Volume 3/2, p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- Isaak, P.J. Religion and Society; Out of Africa Printers: Windhoek, Namibia, 1997; pp. 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tutu, D. No Future without Forgiveness; Double Day: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 187–188. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).