Empirical Evidence Illuminating Gendered Regimes in UK Higher Education: Developing a New Conceptual Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

‘So by populating senate…populating any other committee in an ex officio [capacity] … wouldn’t it be better just to write a constitution for two white men because that’s what you are going to get’[Lucy, University X]

2. Rationale for the Research

The Context for Change

3. The Literature

3.1. Women’s Voice Literature

3.2. Salience of Gendered Cultures

3.3. Masculinity and Remasculinisation of Leadership and Management

3.4. Gender as a Performance

4. Epistemology: Employing a Critical Reflexive Lens

5. Research Design

Data Collection

6. Introducing the Conceptual Framework

7. Presentation and Discussion of Empirical Findings

7.1. Challenges of Gender Denial, and Gendered Hierarchies Becoming More (Rather than Less) Entrenched

‘And I think the things that are valued are the things that are easily measured. And it’s easy to measure grant income, it’s less easy to measure your contribution to making your research team work well, your contribution to running projects well’(Yasmin, University Z)

‘I think probably one of the main things about that is that it’s really hard to compare CVs when people have had time out. So if you have time out because of maternity leave or leaves, you shouldn’t—I really don’t think you should expect to move at the same rate’.(Sue, University Y)

‘REF doesn’t say, “Did you do that work between nine to five?” It says, “Did you do that work?” So you cannot change that ‘.(Yvonne, University Z)

‘I suppose that if there’s an element of gender to it then I would say it’s probably in the way in which promotions, and I’m not just talking about academia here, now they favour a certain attitude to work, they favour a certain tone and a certain confidence that you find more regularly amongst male colleagues’.(Lynn, University X)

“The roles above head of department, there is no route…there is no transparency…almost like a secret society which you might be let into, I’ve no idea how to get into it.”(Lana, University X)

‘We do need more women representation in terms of numbers at certain levels I think to help overcome that tension. Because that leads to a greater understanding of what the issues are. I think one of the problems is that if you’re in a minority any tensions you might be facing are not considered’.(Lisa, University X)

‘When I first became head of department—so this was 2008 I think—the Vice-Chancellor said to me, “You could be a PVC.” And I just went, “Yeah, fine.” And walked away. He didn’t have to say that, and maybe he says it to everybody, I don’t know. But just to plant that seed in somebody’s mind. And that’s what we can do for everyone. We encourage everybody, whether they’re male or female, saying you can do this, don’t be afraid’.(Sandy, University Y)

7.2. Challenge Notion that Gender Discrimination Is a ‘Thing of the Past’

‘So what we don’t want is to fix the issue by putting in a Margaret Thatcher who will simply be a clone of the others but in a slightly different suit. So it’s embracing different styles of leadership’.(Lana, University X)

8. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Broadbridge, A.; Simpson, R. 25 Years On: Reflecting on the Past and Looking to the Future in Gender and Management Research. Br. J. Manag. 2011, 22, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECU. Equality in Higher Education: Statistical Report 2016; Equality Challenge Unit: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jarboe, N. WomenCount: Leaders in Higher Education 2016; KPMG: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EHRC. Sex and Power. London. 2011. Available online: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/sex_and_power_2011_gb_2_.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Leathwood, C.; Read, B. Gender and the Changing Face of Higher Education—A Feminized Future? Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jarboe, N. WomenCount: Leaders in Higher Education 2013; KPMG: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- BIS. Contribution of UK Universities to National and Local Economic Growth; Department for Business, Innovationa and Skills: London, UK, 2015.

- Warwick, D. Women and Leadership: A higher education perspective. In A Speech Given at the Barbara Diamond Memorial Lecture 17 March 2004; Universities UK: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, R.; Schneider, R. The Rationale for Equality and Diversity: How Vice Chancellors and Principals Are Leading Change; Equality Challenge Unit: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tiessen, R. Everywhere/Nowhere. Gender Mainstreaming in Development Agencies; Kumarian Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mushaben, J. Girl Power, Mainstreaming and Critical Mass: Women’s Leadership and Policy Paradigm Shift in Germany’s Red-Green Coalition, 1998–2002. J. Women Politics Policy 2005, 27, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, L. Organising Feminisms: The Micropolitics of The Academy; Macmillan Press: Basingstoke, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, C. 6 Steps to Gender Equality: How Every University Can Get More Women to the Top and Why They Should; Science in Balance Group: Tromso, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. The Business Case for Equality and Diversity: A Survey of the Academic Literature; UK Government: London, UK, 2013.

- CIPD. Managing Diversity: Linking Theory and Practice to Business Performance; Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, M. Women at the Top: Challenges, Choices and Change; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vinnicombe, S.; Sealy, R. Women on boards in the UK: Accelerating the pace of change? In Getting Women on to Corporate Boards: A Snowball Starting in Norway; Machold, S., Huse, M., Hansen, K., Brogi, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Gloucester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bagilhole, B.; White, K. Gender, Power and Management [Electronic Resource]: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burkinshaw, P. Higher Education, Leadership and Women Vice Chancellors: Fitting in to Communities of Practice of Masculinities; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Benschop, Y.; Brouns, M. Crumbling Ivory Towers: Academic Organizing and its Gender Effects. Gend. Work Organ. 2003, 10, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, M.; Benschop, Y. Gender in Academic networking: The Role of Gatekeepers in Professorial Recruitment. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 51, 460–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, M.; Benschop, Y. Gender practices in the construction of academic excellence: Sheep with five legs. Organisation 2012, 19, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, S.R. ‘Unsettling universities’ incongruous, gendered bureaucratic structures: A case study approach. Gend. Work Organ. 2011, 18, 202–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M. Feminisms, Gender and Universities: Politics, Passion and Pedagogies; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, L. Misogyny posing as measurement: Disrupting the feminisation crisis discourse. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2011, 6, 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Priola, V. Being female doing gender. Narratives of women in education management. Gend. Educ. 2007, 19, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesterman, C.; Ross-Smith, A.; Peters, M. ‘“Not doable jobs!” Exploring senior women’s attitudes to academic leadership roles. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2005, 28, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Harding, N. Get back into that kitchen, woman: Management conferences and the making of the female professional worker. Gend. Work Organ. 2010, 17, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkinshaw, P.; White, K. Fixing the women or fixing universities: Women in HE leadership. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.; Knights, D. Reconfiguring resistance: Gendered subjectivity and New managerialism in UK Business Schools. In Organisation Studies Summer Workshop: Resistance, Resisting and Resisters in and Around Organisations; Open University Business School: Corfu, Greece; Milton Keynes, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.; Collinson, D. In Search of the Perfect Manager? Work-life balance and managerial work. Work Employ. Soc. 2011, 25, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltio, I.; Mills, A.; Helms Mills, J. Exploring gendered organisational cultures. Cult. Organ. 2002, 8, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Billing, Y.D. Understanding Gender and Organizations; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie Davey, K. Women’s Accounts of Organizational Politics as a Gendering Process. Gend. Work Organ. 2008, 15, 650–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas-Ozkan, M.; Chell, E. Gender Inequalities in Academic Innovation and Enterprise: A Bourdieuian Analysis. BJM 2015, 26, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, T. Troubling leadership? Gender, leadership and higher education. In Proceedings of the AARE Conference, Hobart, Australia, 30 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Haake, U. Doing Leadership in Higher Education: The gendering process of leader identity development. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2009, 15, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealy, R.H.V.; Singh, V. The Importance of Role Models and Demographic Context for Senior Women’s Work Identity Development. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajcman, J. Managing Like a Man: Women and Men in Corporate Management; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ely, R.; Ibarra, H.; Kolb, D. Taking gender into account: Theory and design for women’s leadership development programmes. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2011, 10, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan-Flood, R.; Gill, R. Secrecy and Silence in the Research Process: Feminist Reflections; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sprague, J. The Academy as a Gendered Institution; Warwick University Feminism Conference: Warwick, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, P. Good jobs - but places for women? Gender Educ. 2015, 27, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebinger, L.; Schraudner, M. Interdisciplinary Approaches to Achieving Gendered Innovations in Science, Medicine, and Engineering. Interdiscip. Sci. Rev. 2011, 36, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, M.; Benschop, Y. Slaying the seven-headed dragon: The quest for gender change in academia. Gend. Work Organ. 2012, 19, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E.F. Protean Organizations: Reshaping Work and Careers to Retain Female Talent. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Carli, L.L. Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J. Discourses of Leadership: Gender, Identity and Contradiction in a UK Public Sector Organization. Leadership 2006, 2, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.L.; Silva, C. The Myth of the Ideal Worker: Does Doing All the Right Things Really Get Women Ahead? In The Promise of Future Leadership: Highly Talented Employees in the Pipeline; Catalyst: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, A.; Mackinnon, A. Gender and the Restructured University: Changing Management and Culture in Higher Education; Society for Research into Higher Education & Open UP: Buckingham, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Brink, M. Scouting for talent: Appointment practices of women professors in academic medicine. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.W. Limits to meritocracy? Gender in academic recruitment and promotion policies. Sci. Public Policies 2016, 43, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Lee, R.; Ellemers, N. Gender contributes to grant funding success in The Netherlands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 12349–12353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, P.; Montez López, E.; O’ Hagan, C.; Wolffram, A.; Aye, M.; Chizzola, V.; Mich, O.; Apostolov, G.; Topuzova, I.; Sağlamer, G.; et al. Micro-political practices in higher education: A challenge to excellence as a rationalising myth? Crit. Stud. Educ. 2017, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalyst. The Double-Bind Dilemma for Women in Leadership: Damned if You Do, Doomed if You Don’t; Catalyst: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, B. Re/theorising gender: Female masculinity and male femininity in the classroom? Gend. Educ. 2010, 22, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, S.; Poggio, B. Gendertelling in Organizations: Narratives from Male-Dominated Environments; Marston Book Services: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Acker, S. Gendered games in academic leadership. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2010, 20, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveline, J. Woman in the ivory tower: Gendering feminised and masculinised identities. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2005, 18, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, V.E.; Mueller, R.; Lituchy, T.; Liu, J. Think manager—Think male: A global phenomenon? J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 17, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, A.L. The philosopher leader: On relationalism, ethics and reflexivity—A critical perspective to teaching leadership. Manag. Learn. 2009, 40, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, D. Crafting Selves, Power, Gender & Discourses of Identity in a Japanese Workplace; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Foucault: Power, Knowledge and Discourse. In Discourse, Theory and Practice: A Reader; Wetherell, M., Taylor, S., Yates, S., Eds.; Sage/OU: London, UK, 2001; pp. 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D. The Stories We Live by: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.; Josselson, R.; Lieblich, A. Turns in the Road: Narrative Studies of Lives in Transition; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, C.; O’Donohoe, S.; Townley, B. Pot noodles, placements and peer regard: Creative career trajectories and communities of practice in the British advertising industry. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 22, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, M. Introducing Narrative Psychology: Self, Trauma and the Construction of Meaning; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.K.; Haslam, S.A. The Glass Cliff: Evidence that Women are Over-Represented in Precarious Leadership Positions. Br. J. Manag. 2005, 16, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, S.; Kramer, V.W.; Konrad, A.M. Critical Mass: Does the Number of Women on a Corporate Board Make a Difference? In Women on Corporate Boards of Directors: International Research and Practice; Vinnicombe, S., Singh, V., Burke, J., Bilimoria, D., Huse, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 222–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kandiko Howson, C.B.; Coate, K.; de St Croix, T. Mid-career Academic Women: Strategies, Choices and Motivation. In Small Development Projects; Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.; Kings Learning Institute, Kings College: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn, C. In the Way of Women: Men’s Resistance to Sex Equality in the Workplace; Macmillan: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Maddock, S.; Parkin, W. Gender Cultures: Women’s Choices and Strategies at Work. Women Manag. Rev. 1993, 8, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J. Inequality Regimes Gender, Class, and Race in Organizations. Gender Soc. 2006, 20, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Broadbridge and Simpson: Developments | Broadbridge and Simpson: Challenges | Broadbridge and Simpson: Futures | Broadbridge and Simpson: Conclusions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Women’s Voice Literature | 1 | Problem of gender has not been solved | 1 | Research must monitor gender difference to inform policy & practice | 1 | Challenges of gender denial |

| 2 | Salience of gendered cultures | 2 | Diversity and silencing of women’s voices | 2 | ‘Tease out’ and conceptualize emerging gendered hierarchies | 2 | Gendered hierarchies becoming more rather than less entrenched |

| 3 | Remasculinisation of Management | 3 | Researching men and masculinities in management | 3 | To reveal hidden aspects of gender and the processes of concealment within norms practices and values | 3 | Challenge notion that gender discrimination is a ‘thing of the past’ |

| 4 | Gender as a performance or doing ‘turn’ | 4 | Discourses of merit and choice | 4 | Responsibility for BJM to publicise outcomes, debates and emergent theoretical frames | ||

| Institution | No. Interviews | Title of Seminar | Seminar Approach | No. Seminar Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | 6 | Different perspectives on the issues, challenges and barriers to achieving more equal representation of women in the professoriate, and ideas for overcoming them | A World Café approach was taken, with each participant selecting two of the four topics to discuss with a small group of other participants. Topics included: reward and recognition; School environment; support and mentoring; working practices. | 14 |

| Y | 4 | In what ways is University Y an enabling/limiting employer for women; ii) Designing ‘The Paragon University of the Consortium | Facilitation: One person sat on each table to gather data and, if required, to support and encourage the participants during the exercises and group discussions:

| 13 |

| Z | 4 | Your Decisions in Focus—Raising Awareness of Unconscious Bias’ | Workshop exploring the impact of unconscious bias on individual and collective decision making. Topics for breakout groups included:

| ~40 |

| All | Dissemination Seminar: | Summary of seminar structure:Presentation of Research Findings and key recommendationsPlenary session inviting delegates’ comments on the recommendations and plans for the next stage of the initiative. | 38 |

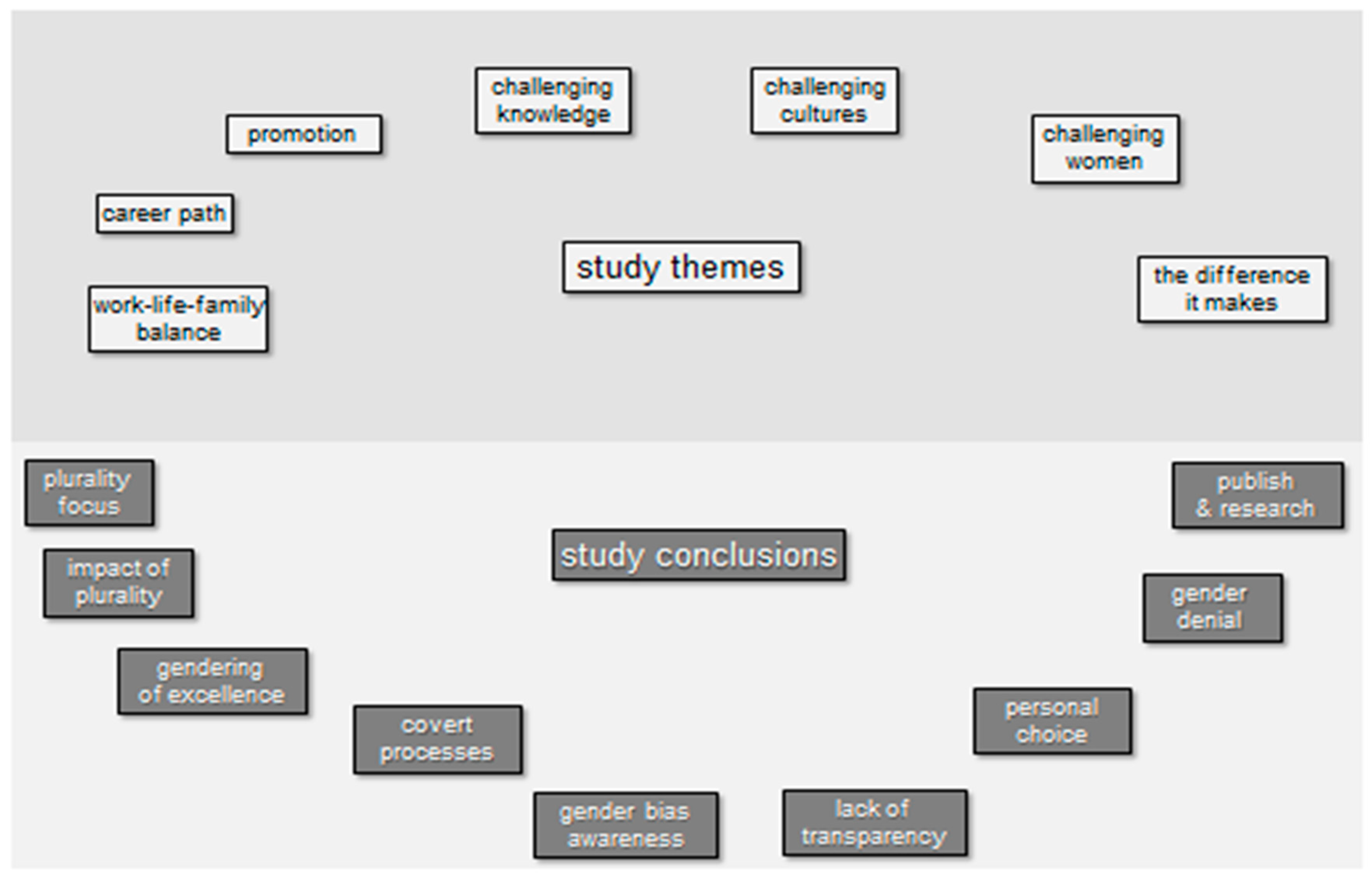

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. The work-life-family balance conundrum | Addresses issues relating to work-life balance focusing on tension between work and family; institutional culture of work life balance and experience of flexible working arrangements |

| 2. The career path-negotiating the trajectory | Addresses individual career trajectories with a focus on professional and personal impacts |

| 3. Promotion: ascending the grading structure and entering the domain of senior leadership | Addresses issues relating to two facets of promotion: progression through the grades/spine points and professorial zones and acquisition of senior management and leadership roles within the institution. |

| 4. Challenging knowledge and ways of knowing | Focuses on cultural barriers impacting on female representation in senior leadership. These are (1) alienating leadership cultures; (2) masculinities cultures. |

| 5. Challenging work and institutional cultures | Addresses examples of positive institutional culture and positive working practices |

| 6. Challenging women | Addresses positive and negative impacts on career development that are perceived to be related to/focused on the individual: (1) success—individual qualities that have led to professional success; (2) ‘blame’—individual qualities that are perceived to hold women back and that are perceived to be specific to women; (3) support—supportive interventions focused on the individual |

| 7. The difference it makes | Focusses on (1) the potential of leadership to impact on future generations and (2) critical mass arguments focusing on whether growing the diversity of leadership can fundamentally effect change and policy in HE |

| Study Findings | B and S Categories | Study Conclusions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Work-life-family balance conundrum (Ch 4) | Developments (D) 1. Women’s voice literature |  | 1 Plurality rather than gender focus (Ch1) | |

| 2 Career path—negotiating the trajectory (D2; Ch3) | 2. Salience of gendered cultures | 2 Impact of plurality (D3) | ||

| 3 Promotion (D2; Ch3) | 3. Masculinity and remasculinisation | 3 Gendering of excellence (D2) | ||

| 4 Challenging knowledge and ways of knowing (D2; D4; Ch2; RP3 | 4. Gender as performance | 4 More covert processes playing out (C3) | ||

| 5 Challenging work and institutional cultures (D3; RP2) | Challenges (Ch) | 5 Gender bias awareness training (C2) | ||

| 6 Challenging women (D1; Ch2; Ch4) | 1. Problem of gender has been ‘solved’ | 6 Lack of transparency (C2) (RP3) | ||

| 7 The difference it makes (Ch1; RP1) | 2. Diversity and silencing of women’s voices: dilution of women’s voices through focus on diversity research | 7 Personal choice? (Ch2) | ||

| 3. Researching men and masculinities in management | 8 Evidence of gender denial (C1) (C2) | |||

| 4. Discourses of merit and choice | 9 Responsibility to publish/research (C4) | |||

| Research Priority (RP) | ||||

| 1. Inform policy and practice | ||||

| 2. Emerging hierarchies | ||||

| 3. Reveal covert processes | ||||

| Conclusions (C) | ||||

| 1. Challenge of gender denial | ||||

| 2. More entrenched | ||||

| 3. Not thing of the past | ||||

| 4. BJM responsibility to publish |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burkinshaw, P.; Cahill, J.; Ford, J. Empirical Evidence Illuminating Gendered Regimes in UK Higher Education: Developing a New Conceptual Framework. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8020081

Burkinshaw P, Cahill J, Ford J. Empirical Evidence Illuminating Gendered Regimes in UK Higher Education: Developing a New Conceptual Framework. Education Sciences. 2018; 8(2):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8020081

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurkinshaw, Paula, Jane Cahill, and Jacqueline Ford. 2018. "Empirical Evidence Illuminating Gendered Regimes in UK Higher Education: Developing a New Conceptual Framework" Education Sciences 8, no. 2: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8020081

APA StyleBurkinshaw, P., Cahill, J., & Ford, J. (2018). Empirical Evidence Illuminating Gendered Regimes in UK Higher Education: Developing a New Conceptual Framework. Education Sciences, 8(2), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8020081