Abstract

With the exponential advancement of technology, global sharing, industrialization and economic development, national and global cultures are becoming more collective. More importantly, this fundamental paradigm shift is affecting national and global educational leadership cultures. Therefore, the power/distance index (PDI); individualism versus collectivism (IDV); uncertainty avoidance index (UAI); masculinity/femininity (MAS); and long-term orientation versus short-term orientation (LTO); are of interest when considering national and global cultures. These cultural dimensions can be exemplified in the responses of eight female educational leaders: three Canadians and one from Jamaica and Trinidad; two Grenadians and one Lebanese. This qualitative methodology in the form of a phenomenological study found that all respondents displayed varying degrees of each aspect of Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions which can be charted along a continuum from high to low index factors. Each dimension is linked to different leadership styles. PDI is linked to servant leadership, IDV is linked to shared/participatory leadership, UAI is linked to transformational leadership and emergent leadership, and MAS is linked to people versus task-oriented leadership. In each case, the slight variances in responses reflect the microcosm of the macrocosm where each country’s particular culture is mirrored. Recommendations are made for a more androgynous leadership style as well as more androgynous socialization processes if national and global educational leadership cultures are to become less gendered and more instrumental and functional based on the demands of the particular environment. It is expected that a focus could be placed on transcultural rather than intercultural studies in leadership and education.

1. Introduction

Hofstede [1] defined culture as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people form another” (p. 39). This implies the use of explicit information to form tacit knowledge and determine what distinguishes one group from another. On the other hand, leadership is described by Cole [2] as a dynamic process whereby an individual influences another individual to contribute voluntarily to the realization and attainment of the goals, objectives, and aspiration of values of the group. In considering these two definitions one can see that culture and leadership share an interdependent relationship where one feeds the other and vice versa. Put simply, culture and leadership research share one commonality that leadership across cultures varies in the extent to which each leadership style is implemented. Indeed, House, Wright and Aditya [3] concluded that the expectations of what defines leadership behaviours varies across cultures. They determined that the effectiveness of task-focused and people-focused behaviours are culture-specific.

1.1. Overview of Literature on Culture and Leadership

The power/distance index (PDI) measures the “extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally” [4] (p. 521). In societies where there is evidence of a high PDI, hierarchical structures are in place and there are rigid positions of leaders and subordinates. In such organizations, subordinates are seen as dependent on their bosses. Power is limited to a few individuals with gaps in earnings between the bosses and the subordinates. According to Wursten and Jacobs [5] in societies with high power distance, old age is respected and everybody has his/her rightful place. The opposite occurs in countries where the power/distance is low where people try to “look younger and the powerful try to look less powerful” (p. 7).

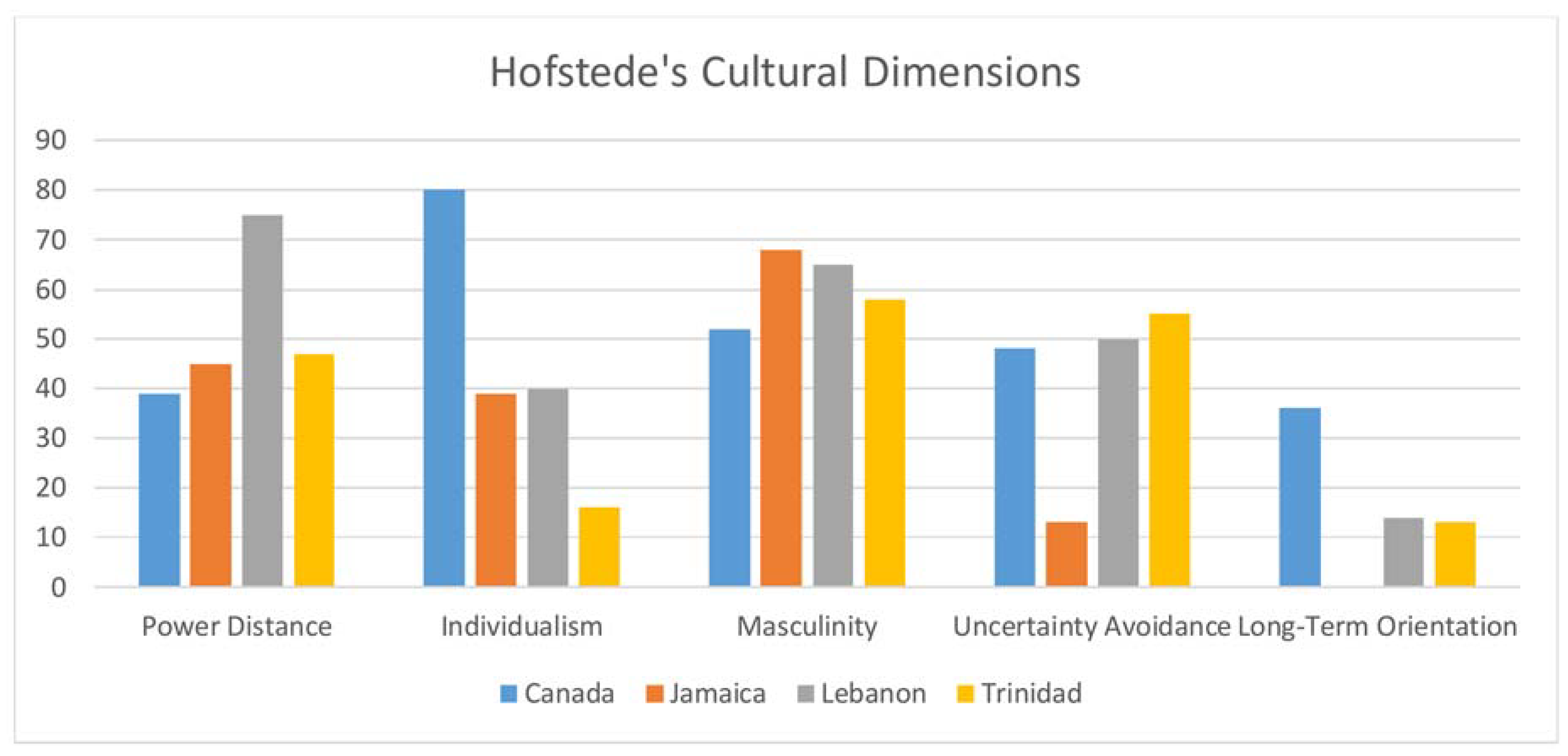

Hofstede’s [6] 6D model website did not show any country scores for Grenada. Figure 1 was generated from Hofstede’s website and provided the following information based on the other four countries involved in this study. Wursten and Jacobs [5], in their discussion of the scores per country, indicated that the scores were from 0 to 100 and that the scores should not be taken as a representation of every individual in the society but as a representation of the collective individuals in the society.

Figure 1.

Hofstede’s 6D model applied to each country [6].

Figure 1 shows that the PDI score for Lebanon is very high at 72 and Canada has the lowest score of 39 where there is more interdependence “among its inhabitants and there is value placed on egalitarianism” [6] (p. 1). According to Wursten and Jacobs [5], a low power-distance in teaching is one that is student-centred, capitalizes on students’ initiatives, and where students learn by discovery. A high power-distance is a teacher-centred classroom (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Implications of power-distance on teaching [5] (p. 7).

Similarly, within the context of leadership, decisions are made by the leader and the leadership style is authoritative. The emphasis is on close monitoring and evaluation of the subordinates to ensure that there is a high level of performance and productivity [7]. The opposite of this is servant leadership which is embodied by the principal’s service to the key stakeholders and the wider community [8]. Al-Mahdy et al. [8] administered the servant leadership scale (SLS), Barbuto and Wheeler, and the job satisfaction survey (JSS), Spector, to 356 Omani teachers and found that teachers indicate moderate levels of satisfaction when principals displayed servant leadership.

Hannay [9] found that servant leaders operate in situations where there were low power-distance and employees participate and interact. In such a climate, subordinates are able to freely express their ideas and willingly engage in the decision-making process. They feel valued and appreciated and there is a high level of risk taking as they willingly share their opinions and expect to be heard [9]. West and Bocarnea [10] implemented the servant leadership scale from Hale and Fields (2007) to measure servant leadership in two higher educational institutions in the United States and the Philippines. There were differences in the subscales of the groups in the dimension of vision. However, there were no significant differences found in the dimensions of vision and humility.

In an individualistic society “the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after himself or herself and his or her immediate family only” [4] (p. 92). Individuals are mainly concerned with self-interest and work is aligned along the lines of fulfilling individualistic economic and psychological needs. Diametrically opposing this is collectivism where there is a cohesive group and societies and organizations work as communal groups. Collaboration, team-work, mutual dependence, loyalty and relationship-building are the hallmarks of such a society. This collectivism is more utilitarian in its value system where the interests of the group are more important than disparate members.

From Figure 1, Canada scored the highest which suggest that Canadians do not look after themselves and their immediate families. In this environment, employees are expected to be self-reliant and show initiative. Trinidad scored the lowest which indicates that Trinidad is more collective which means that the population is more “we” oriented versus “I”. According to Hofstede (2017), “In collectivist societies, people belong to ‘in groups’ that take care of them in exchange for loyalty” (p. 1). According to Wursten and Jacobs [5], in a collectivist teaching environment, students only speak when they are spoken to, students speak in small groups, harmony is embraced, the teachers and students do not lose face and favouritism is shown for some based on ethnicity and affiliation. In an individualistic society, students are invited to speak by the teachers, students speak in large groups, there are confrontations and challenges, one party may lose face, and teachers are impartial (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Implications of collectivism versus individualism (IDV) in teaching [5] (p. 8).

Shared/participatory leadership is one where the entire team/organization share in the leadership and the decision-making process [11]. In this context, there is interaction among team members as they share leadership responsibility and tasks [12]. Indeed, shared/participatory leadership is seen as part of the social fabric of the team [13] and is closely linked to group collaboration. Bolger [14] conducted a quantitative study of the impact of principals’ leadership styles on 940 teachers and found that the principals who practiced participative decision-making had higher teacher satisfaction ratings than those principals who used autocratic decision-making. Teachers felt a sense of ownership and liked that they had a say in the decision-making process.

According to Hofstede [15] uncertainty avoidance is the “extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations and have created beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these” (p. 21). There is strict adherence to rules and regulations for behaviour and prescribed codes of conduct. Any behaviour or idea that is not within the frame of reference is not tolerated. A weak uncertainty avoidance ındex comprises societies that maintain a more relaxed attitude where praxis counts more than rules and regulations [4].

Jamaica scored the lowest in uncertainty avoidance which indicates that it is far more accepting of uncertainty where new ideas are embraced, there is an emphasis on innovation, a spirit of entrepreneurship is encouraged, and change management is easier to implement. According to Hofstede [6] such cultures are not “rules-oriented and tend to be less emotionally expressive than cultures scoring higher on this dimension” (p. 1). However, Canada, Lebanon and Trinidad scored higher in uncertainty avoidance which indicates that such countries have a strong “emotional need for rules and formality to structure life” (p. 11). Within the teaching and learning setting, a low uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) score shows that students are more comfortable when there is less structure, teachers can say “I don’t know”, students are encouraged to be creative and innovative, and critical thinking and analysis with intellectual sound arguments being encouraged (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Implications of collectivism versus individualism in teaching [5] (p. 11).

In the discussion of leadership and culture, Muenjohn and Armstrong [16] indicated that “certain leadership behaviours are likely to be particular to a given culture, whereas others argue that there should be certain structures that leaders must perform to be effective, regardless of cultures” (p. 265). Regardless of the leadership processes, Liu and Lee [17] found that there is a link between cultural dimensions and transformational leadership. Transformational leadership [18] entails the development of followers into leaders and creating an environment of change. Transformational leadership encompasses the four Is (Idealized Influence; Inspirational Motivation; Intellectual Stimulation; and Individualized Consideration). Idealized influence (II) encompasses a leader who is able to model the expected behaviour of his/her subordinates [19]. He/she possesses high morals and fosters a climate of trust [20,21].

Studies on the significant impact transformational leaders have on teachers’ motivation and job satisfaction attest to the value of having transformational leaders within the school setting [20,22]. In fact, Kruger, Witziers, and Sleegers [22] found that transformational leadership positively influenced teacher motivation, professional growth, and school culture and contributed to educational change. Earlier, Jung, Bass, and Sosik [23] determined that collectivistic cultures foster transformational leadership more than individualistic cultures. Moreover, Dorfman [24] indicated that all aspects of transformational leadership behaviours can be typical of excellent leadership regardless of the culture. Additionally, Spreitzer, Perttula and Xin [25] found a relationship between cultural values, transformational leadership, and leadership effectiveness.

Bass [26] indicated that transformational leadership could be successfully applied across cultures. Ergeneli, Gohar and Temirbekova [27] found a significant negative correlation between two components of transformational leadership and uncertainty avoidance. They discovered that such dimensions as “challenging the process and enabling others to act were not found to be related to any of the culture value dimensions” (p. 703) whilst some aspects of transformational leadership were found to be prevalent among all cultures and not culture specific. They concluded that “inspiring a shared vision and modelling the way were significantly and negatively related to uncertainty avoidance while encouraging the hearth was positively related to power distance” (p. 703).

An emergent leader is one who comes to be seen as a leader by other members of his/her group [28,29]. In emergent leadership, individuals become informal leaders based on their contributions and their influence [30]. According to Charlier [30], “emergent leadership is focused at the individual level, and is derived from the perceptions of others as they relate to a single person” (p. 20). Carte, Schwarzkopf and Wang [31] stated that culture affects an individual’s desire to become or exemplify emergent leadership skills. In fact, in cultures where there is a strong male dominance, it is easier for a man to emerge leader rather than a female [32]. However, within the online environment, there seems to be a level playing field where women’s chances of becoming leaders are increased [33]. Nevertheless, culture continues to be a critical factor in whether individuals will choose to become leaders within the team environment [34].

According to Eagly and Koenig [35], males are agentic and females are communal and roles are prescriptive rather than injunctive. A society that is high on masculinity is driven by competition, achievement and success. Males are expected to be tough, brawny, natural leaders, materialistic and assertive in societies where there is a high masculinity/femininity (MAS) index [36]. Females are expected to follow, be soft and gentle and more concerned with quality and nurturing [4]. Naturally, in societies where there is a higher MAS index, there is more competition with decisions made based on strength rather than consultancy and mediation. In such a society, people work to earn more money and there is less leisure time. Rewards are based on equity and there are less women in the professional workforce.

Jamaica and Lebanon scored the highest in the MAS index which suggests that these countries are more androcentric and the roles of both genders are more clearly delineated than those of Canada which scored the lowest with 52 and can be characterized as a moderately masculine society.

Within the teaching and learning situation, Wursten and Jacobs [5] indicated that teachers who were more masculine-oriented used the best students as exemplars, encouraged a system of academic reward, saw academic failure as part of the self-image, students ensure that they are visible and they think about their career path and choose subjects based on their future career path. Conversely, teachers who are more feminine, praise the average students, commend social adaptation, failure is not seen as the be all and end all, and students choose subjects based on interest (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Implications of femininity versus masculinity in teaching [5] (p. 10).

Miller [37] stated that school leadership in the Caribbean and globally is dominated by females since there are more females in the workforce. He furthered that school leadership is viewed as a male domain, however, “women have negotiated the gendered nature of their professional lives” (p. 181). He opined that women have made great achievements in being able to acquire leadership roles in a male-dominated society. When placed in leadership positions, Muhr [38] contended that females perpetuate gender equality by becoming excessively masculinized and feminized. Such polarity in one individual would suggest that the female leader capitalizes on her feminine nurturing element and also goes according to tradition and emulates masculine-type leadership [39]. Muhr [38] further explained:

One could even argue that our culture has produced a generation of superwomen—women who do not compromise, at any level. Their striving for recognition and success has thus created a type of female leader who, in her quest for perfection, transcends gender stereotypes while extremizing them, becoming something like a super-leader.(p. 338)

This is also the case in her study of 115 Jordanian women leaders who were found to display both masculine and feminine leadership styles in the form of task-oriented and people-oriented leadership styles. Task-oriented individuals are concerned with getting the task completed and people-oriented leadership prefer to expend their efforts building relationships and honing the organization’s social systems [39]. This would suggest that female leaders tend to exercise both communal and agentic qualities, see themselves as products and producers of their social system, and display descriptive and/or injunctive and prescriptive patterns of behaviour [40].

Long-term orientation is geared towards delayed gratification and long-term goals are made. This society fosters thrifty behaviours, perseverance and adaptation to changing circumstances for future rewards [4]. Leisure time is not as important as living frugally and achieving long-term goals. On the other hand, a short-term oriented society is more about leisure time, freedom, short-term achievement, and individualistic. Normative societies score low on this dimension and are more concerned with adhering to traditions and norms. Such societies do not embrace change readily.

Jamaica scored the lowest in this dimension with zero which shows that its approach to societal change is more about adhering to the tried and true norms. Lebanon and Trinidad scored 14 and 13, respectively, which is not much higher than Jamaica. Canada scored 36 in this dimension which suggests that all the countries in this study are normative in their approach to long-term orientation. In these societies, citizens are more concerned with respect for traditions. Within the teaching and learning setting, the society that scores low on this is one where students ask why, only one solution is considered, and stability is very high (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Implications of long-term orientation in teaching [5] (p. 13).

1.2. Problem Statement

Culture and its impact on leadership, especially school leadership, is an under-researched topic as evidenced in Google searches conducted on 31 January 2015 and on 30 December 2017 of Hofstede’s [1] five dimensions. The search revealed scant studies pertaining to school leadership and the cultural dimensions. Dissertations and articles were found on Hofstede’s dimensions and leadership in other domains but not in education. Such scarcity in information led the researcher to contemplate conducting this study. In checking Hofstede’s cultural dimension scores for Grenada, one of the countries in this study, there were no scores. This suggests that there is a need for more studies to be conducted on such countries. Moreover, Schein [41] and Liu and Lee [16] highlighted the need for expanded studies on leadership and culture as a means of understanding the underlying tacit factors that affect organizations.

1.3. Purpose of the Study and Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to apply Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions to eight female educators’ discussions to determine the similarities and differences that exist and co-exist.

The following research question guided this study:

How representative are the eight female participants’ discussions of themselves as leaders to Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Population

Purposive sampling is used in qualitative research for the “identification and selection of information-rich cases related to the phenomenon of interest” [42] p. 533. The criteria chosen was educational leadership in different cultures. The sampling method used was purposive since the participants were selected because they were known to be educational leaders and held leadership positions in educational institutions. A total of 15 emails were sent to male and female leaders known to the researcher and only eight females responded.

One Canadian female is a Literacy Lead and holds a Masters in Exceptional Leaners. She has extensive teaching and leadership experiences. The two Canadian principals both have Masters in Education and have extensive experiences in teaching and principalship. The Jamaican participant is an online educator and leader. She holds a Phd. She started in the classroom and then conducted staff development workshops. She became a teacher trainer and consultant. The Trinidadian participant, at the time of the interview, was a head of department and has now moved into an acting vice principal position. She had been at that school for 11 years. She has a Masters in Educational Administration.

The Grenadian participant has a Bachelor in Educational Leadership and has spearheaded an online Facebook page for Grenadian teachers in order to create synergy and cohesion among them. She has been a teacher for 20 years. Before being promoted to principal, she was a teacher, head of department and vice principal. The second Grenadian participant is currently pursuing her Masters in Educational Administration and has been teaching primary school for the past 20 years. The Lebanese participant is currently the head of student services in a bilingual school in Kuwait. She possesses extensive experience in Cyprus, Egypt, Switzerland, Cairo, Beirut and Kuwait.

2.2. Design and Instrumentation

A qualitative research design using the phenomenological approach allowed the participants to discuss leadership based on their experiences [43]. Phenomenology can provide valuable knowledge of the participants’ perceptions subjectively rather than through a cause and effect approach [44]. Data was collected from interview questions which were divided into sub-sections. Each sub-section included the: (1) background information; (2) defining leadership; (3) leadership skills; (4) leadership challenges; and (5) conclusions. Participants were asked questions such as: What do you perceive as the benefits and drawbacks to working in an educational setting as opposed to a corporate environment? What type of leader would you say you are and why? Give an example. The questions were designed based on the concept of leadership.

2.3. Validity and Reliability

2.3.1. Validity

According to Leung [45], validity refers to the “tools processes and data and whether the research question, the methodology is valid” (p. 325). In this case, the items used were interview questions on leadership and the responses related to Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions. In hindsight, it would have been more appropriate to: (1) adapt the interview questions from other questions used in previous studies [46]; and (2) conduct a pilot of the interview questions to ensure that they were valid and responded to the research question.

2.3.2. Reliability

According to Leung [45], reliability can be obtained in qualitative research via comprehensive data use, constant data comparison, and verification of findings with the participants as a form of triangulation [47]. The data was compared with the current available research, however, triangulation of data did not take place.

2.4. Data Collection

An electronic mail (e-mail) containing a list of interview questions were emailed to 15 male and female educational leaders. Eight female participants responded to these e-mails from 27 February to 7 March 2015. These eight women range from ages 40 to 60 years old and have been in education for more than 20 years.

2.5. Data Analysis

Johnson, Dunlop and Benoit [48] suggested that the researcher, carefully read the data, identify the emerging themes and determine the quotes to be used to substantiate the themes. The participants’ responses were read and re-read and coded and re-coded according to Hofstede’s five dimensions to determine the index factor of each along a continuum.

3. Results

Table 6 shows the five dimensions and the relationship to each leadership style exemplified by the eight female leaders and the particular scores for each country.

Table 6.

Comparison of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, participants’ leadership styles; and nationality and scores.

Hofstede’s Five Dimension and Leadership

The scores for Trinidad for each of the areas indicated: PDI is 47; IDV is 16; MAS is 58; UAI is 55; and LTO is 13 (see Table 6). The Trinidadian educational administrator indicated that she saw herself as a servant leader and tried to serve as best as she could. She stated that she admired Mother Theresa because she was all “about leading by example and service”. However, the Lebanese educational administrator stated, “I see myself as a mix of a transformational and servant leader”. She continued, “The personal needs of my followers are important”. The score for power/distance for Lebanon was 75 (see Figure 1) which gives it a relatively high score.

The eight participants were interested in the development and improvement of their subordinates and in the general good for all. The Lebanese participant stated:

An effective leader strives to be obsolete. An effective leader develops in others responsibility and independence, instils self-confidence, to the point than he/she becomes obsolete and his/her followers become leaders in their own rights.

This would substantiate the 40 scored by Lebanon in individualism and collectivism where they are seen to be more collective and community-driven. This sentiment was echoed by the Canadian principal who saw herself as “a compassionate leader that tries to see the best in people”. She further stated, “I encourage leadership in others and really try to bring harmony into the school environment”. Another Canadian, the Literacy Lead, also indicated that she was interested in the well-being of the subordinates. She saw herself as “a partner rather than a leader”. She said that she hoped to help (her teachers), “refine their practice and grow professionally”. This demonstrates a culture of collectivism where the leader takes care of the followers and utilitarianism is practiced. It must be noted that this is in contrast to the high score of 80 given for Canada in favour of individualism. Therefore, this participant’s response could be the exception rather than the rule. More research in this area would determine whether this is so or not.

The Grenadian participant echoed that she hoped to develop “leaders through positive involvement instead of always being followers”. This includes participatory leadership which the Trinidadian participant stated that she was. She saw herself as allowing “great input from the members of my staff re ideas, changes. We, for the most part, make decisions as a team and I always look for ways to enhance their morale”. She added that she tries to “get to know and build my people, help them to grow. Even the delegation of tasks becomes easier when you truly know your employees because you know who to assign what and when”. In fact, she mentioned an issue with one of her teachers who was always submitting her grades late and she sat with her and tried to guide her through the process so that she would not be submitting grades late. This attitude is in agreement with the low score of 16 on individualism for Trinidad.

Inspiring a shared vision and modelling the way relate to idealized influence and inspirational motivation. The Trinidadian participant indicated that she also saw herself as a transformational leader. She stated:

I also practice the transformational style of leadership because again I seek ways to enhance productivity by allowing for a lot of communication amongst us with the aim of transforming ourselves and by extension the institution for the better. In a nutshell, I see myself as a facilitator for the greater good of the institution. I do not even like to use the term “leader”.(Personal communication, 1 March 2015)

She continued that effective leadership is, “Setting an example to others of what you would want of them. Therefore, exactly what I am asking of them they should be able to see in me-giving of myself 110%”. All of this exemplifies the four Is of transformational leadership.

Similarly, one of the Canadian principals opined:

I have more of a coaching and/or transformational leadership style. I do my best to motivate teachers and enhance productivity and efficiency through communication and high visibility. I focus on the big picture and always do my best to be part of the team to accomplish goals. Most importantly an effective leader will be humane. It is okay to make mistakes, take risks, misunderstand, dream big, and have a life after hours with family. Equally, one must remember and value that the school is made of humans who, too, make mistakes, take risks, misunderstand, dream big, and have a life after hours with family. An effective educational leader should want to positively impact the whole system by professionally facilitating school culture, professional development and system-wide innovation.

The Canadian Literacy Lead indicated that an effective leader is one who coaches. Another Canadian principal stated, “My former principal who I consider my mentor. She was always encouraging and praising my strengths. She was kind and fair to all and had a sense of humour”. Another Canadian principal stated:

Some of the main lessons I have learned from my mentors is to always lead by example, be visible to teachers and students, and to always communicate a vision that animates, motivates, and inspires your staff.

These exemplify that these leaders saw themselves as transformational leaders who exemplified idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation and individualized consideration.

The Jamaican participant saw herself as an emergent leader who “coaches and facilitates leadership in others”. She sees part of this emergent leadership as both facilitative, coaching and situational. She added:

It is important that leaders be results-oriented and take the initiative to make changes as this will dive the organization to achieve objectives more than high-level meetings and external findings.

This idea of emergent leadership is in agreement with Jamaica’s low score of 13 for uncertainty avoidance which indicates that it is tolerant of changes and open to accepting diversity, differences in opinions and ambiguity. This is different from the findings on each country for uncertainty index where Trinidad, Canada and Lebanon scored below 50. It would also corroborate the idea that the online environment offers increased equality for all and women emerge as leaders as much as men.

Seven of the eight participants indicated that they capitalized on this nurturing quality. The Trinidadian participant indicated that she was a people-oriented leader despite making it as the first female vice-principal of a secondary boys’ school, she did not lose her femininity and actually capitalized on it in her leadership. Nevertheless, Trinidad scored relatively high in the masculinity/femininity index. The Trinidadian participant stated:

The people in my department tell me I am very maternal, some refer to me as a big sister or as a mummy to them so I would like to think it is that maternal instinct they are perceiving in me that probably endears them to me. Mothers for the most part are synonymous with love and care so this is what I try to portray I guess.

One Canadian principal opined:

I think my nurturing quality has come from being a mom—especially a mom with a child with some delays. I was a firm, but loving teacher before I had children. However, my whole being changed the minute I became a mom. I wish I could take back every PT interview and every report card comment before I was a mom. I was very harsh. I can see that now. I try not to think about my early days of teaching. When you know better—you do better.

The Grenadian participant echoed similar sentiments and said:

Counselling, showing empathy, providing food and clothing for the indigent, by starting a breakfast program, visiting and sending greeting cards to community members and parents when they are celebrating or grieving. Starting literacy sessions for parents who are illiterate.

Another Canadian principal shared, “With the parents and the children. Truly understanding how they feel and nurturing the little ones. They know that I truly care for them”. The Canadian Literacy Lead stated:

I do feel I have used my nurturing qualities (which is not just a feminine trait) in my role. I have given many hugs to overworked, overstressed teachers and they know they can come to me with personal problems as well as professional ones.

Another Grenadian participant stated:

As a woman, who studies indicate tend to show care in more passionate and persistent ways. I have used such inherent qualities to ensure that the group always work as a team (no power struggle) to get the work done effectively.

In contrast, the Lebanese participant was more concerned with ensuring that she takes care of the “small details to keep my staff comfortable at work”. This displays more task-oriented behaviours. Similarly, the Jamaican participant showed a more task-oriented approach to leadership but did not disclaim her people-centred leadership style. She explained:

I think that I have been able to build strong relationships but cannot attribute it to the female nurturing role as a man may do it just as well. For example, if a facilitator is ill or has a parent that is ill I would follow up and ask how the person is doing and share some advice or coping strategy.

It must be noted that Canada scored the lowest for masculinity orientation in Hofstede’s dimension with Jamaica scoring the highest, which indicates more adherence to task-oriented leadership.

The Jamaican online educator suggested that incoming educational leaders both online and face-to-face need to:

Have a clear vision of what you want to achieve through the post and set goals. Develop the skills of time management and communication and most importantly be prepared to build and motivate your team to understand and carry out all required tasks to a high level of quality regardless of how big or small these are.

These qualities reflect transformational leadership where the leader is seen as a motivator. Therefore, although she said she saw herself as an emergent leader, her words of advice demonstrate that she considers transformational attributes as being responsible for her success as a leader.

The Trinidadian participant indicated that she would advise young leaders to, “to be prepared to serve, to be all that you are asking of others to be”. This shows that albeit, she indicated that she saw herself as a participatory/shared and transformational leader, she was also a servant leader in her belief as to what made her successful.

The Grenadian participant resonated shared/participatory leadership when she advised:

Dream big, find the right people to dream with, work as a team to achieve success, let the little that you have work for you, keep the lines of communication open at all times, do not discriminate or block the contributions of others, value everyone, be yourself and be honest. Show love and empathy for each other and, most of all, be respectful to everyone.

It must be noted that three participants mentioned the importance of open communication. The second Grenadian participant stated:

My advice would be to have clear vision of what you want to achieve through the post and set goals. Develop the skills of time management and communication and, most importantly, be prepared to build and motivate your team to understand and carry out all required tasks to a high level of quality regardless of how big or small these are.

When asked about the qualities that they believe society looks for in an educational leader, all eight leaders indicated that honesty, strong morals and fairness were the most significant attributes. The Trinidadian participant stated, “They value strong, morally sound individuals. They seem to also value individuals who would be transparent and fair in their leadership”. The Jamaican participant opined, “The society values honesty, responsiveness and negotiation for goal setting and timelines”. The Grenadian participant stated, “Honesty, integrity, inclusive governance, integrity and transparency”. The Lebanese participant stated, “You must never compromise your ethics, no matter how difficult the situation is, no matter what you can lose. Your ethics, your values, is your legacy”.

One of the Canadian principals stated:

One cannot be an effective leader without first having self-awareness. Having the ability to see we are not perfect or when we have made a mistake allows us to see other peoples’ perspectives. If we can acknowledge our flaws, we can make positive change to improve upon them. However, knowing one’s strengths is also beneficial as it allows the leader to use them efficiently and to model best practices.

Another Canadian principal advised, “Be understanding of staff, always be willing to extend a helping hand, be kind and compassionate. Delegate and share your leadership. Encourage staff to become leaders”. The Canadian Literacy Lead stated:

Advice I would give to others hoping to take over my role is work first with those who want your help. Their enthusiasm will motivate others. Share experiences, listen carefully, use specific praise and master effective observation and questioning techniques. Keep current in your learning, value youthful drive and older experience. Let others know you are equals fighting in the same trenches and experiencing the same joys.

The advice from these participants demonstrate that they are geared towards improving themselves, their subordinates and their society. It also demonstrates that, when it comes to their expectations of the next generation, they do not differ based on the cultural norms espoused for long-term orientation as indicated by Hofstede (1997). It can be noted that the Jamaican participant’s advice was more task-oriented and illustrated that Jamaicans scored lowest in the long-term orientation index.

4. Discussion

From the discussion, it can be seen that differences and similarities exist for each dimension [15]. Differences in responses and lack of adherence to other findings on each cultural dimension could be determined if a more extensive mixed methodology study were to be conducted. Such a difference could be individual rather than collective which is another issue Miller [37] highlights that should be taken into consideration when discussing women’s leadership.

According to Hannay [9] servant leadership thrives in a culture where there is “low power distance, low to moderate individualism, low to moderate masculinity, low uncertainty avoidance and a moderate to high long-term orientation” (p. 1). The Trinidadian educational administrator’s comments on the importance of being a servant leader are similar to this and not in agreement with Hannay’s [9] findings on power distance and servant leadership. However, in her ability to nurture her followers, this agrees with Eagly and Koenig’s [35] view that women tend to be more interested in cultivating relationships, nurturing others and are more people-oriented. Women are also seen as more relationship-oriented whereas men are more task-oriented [35]. The participants in this study exemplified this nurturing communal quality. This quality is also linked to collectivism and participatory leadership which resonated from the participants’ discussions [11,12,13]. This is also seen as being more people-oriented rather than task-oriented leadership. The participants’ responses are not in agreement with Muhr’s [38] and Rayyan’s [39] findings that females, when placed in leadership positions, display masculine-type leadership. However, these responses reflect Bissessar’s [40] conclusions that female leaders tend to capitalize on their communal qualities when leading [35] and are more compassionate and caring.

Transformational leadership relates to a low uncertainty avoidance index which is expected of leaders who look to motivate and inspire their subordinates to transcend their capabilities. Jung, Bass and Sosik [23] who found that a more collectivistic society fosters transformational leadership which is similar to what they participants indicated in their discussions. Their discussions are similar to findings by Ergeneli, Gohar and Temirbekova [27] who concluded that inspiring a shared vision and modelling the way are negatively correlated to uncertainty avoidance. In this study, the Trinidadian and Canadian participants indicated that they were committed to sharing a vision and serving as exemplars which shows low uncertainty avoidance, however, the counties’ scores showed average uncertainty avoidance which could indicate that these participants could be the exception rather than the rule.

5. Conclusions

From the findings, it can be seen that school leaders have the task of providing intellectual stimulation and individual support [49] and establishing positive working relationships with key stakeholders in order to promote school improvement and change. The eight participants in this study demonstrate aspects of leadership in relation to Hofstede’s five dimensions. A mixed methodology study showing a correlation between leadership styles and Hofstede’s cultural dimension would add to the current literature on leadership and culture.

6. Recommendations for Future Research

The following are recommendations for future research:

- The study should be replicated with a larger sample size of both males and females;

- A more robust interview questionnaire should be used, piloted and adapted from other researchers;

- A mixed methodology would be more effective in complementing the qualitative data with the quantitative data;

- Studies should place more emphasis on linking Hofstede’s five dimensions to the various leadership styles. A correlational analysis of the two variables could provide compelling fodder for discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Hofstede, G. Cultural dimensions in people management. In Globalizing Management: Creating and Leading the Competitive Organization; Pucik, V., Tichy, N., Barnett, C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, G.A. Personnel and Human Resource Management; ELST Publishers: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- House, R.J.; Wright, N.S.; Aditya, R.N. Cross-cultural research on organizational leadership: A critical analysis and a proposed theory. In New Perspectives in International Industrial Organizational Psychology; Earley, P.C., Erez, M., Eds.; New Lexington: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 535–625. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival, Revised and Expanded 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wursten, H.; Jacobs, C. The Impact of Culture on Education. 2013. Available online: http://geerthofstede.com/tl_files/images/site/social/Culture and education.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- Hofstede, G.H. Cultural Tools Country Comparison. 2017. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries/ (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- Goolaup, S.; Ismayilov, T.; Eriksson, J. The Influence of Power Distance on Leadership Behaviours and Styles. 2011. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:502384/fulltext01 (accessed on 6 May 2018).

- Al-Mahdy, Y.F.H.; Al-Harthi, A.S.; El-Dina, N.S. Perceptions of School Principals’ Servant Leadership and Their Teachers’ Job Satisfaction in Oman. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2016, 15, 543–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannay, M. The cross-cultural leader: The application of servant leadership theory in the international context. J. Int. Bus. Cult. Stud. 2009, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- West, G.R.B.; Bocarnea, M. Servant leadership and organizational outcomes: Relationships in United States and Filipino higher educational settings. Presented at the Servant Leadership Roundtable at Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, N.J.; Day, D.V.; Vance, R.J. Collective enactment of leadership roles and team effectiveness: A field study. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.G.; Ropo, A. Leadership and faculty motivation. In Teaching Well and Liking It: Motivating Faculty to Teach Effectively; Bess, J.L., Ed.; Johns Hopkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997; pp. 219–247. [Google Scholar]

- Dachler, H.P. Management and leadership as relational phenomena. In Social Representations and the Social Bases of Knowledge; Von Cranach, M., Doise, W., Mugny, G., Eds.; Haupt: Bern, Switzerland, 1992; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, R. The influences of leadership styles on teacher satisfaction. Educ. Adm. Q. 2001, 37, 662–683. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.H. Culture and Organization: Software of the Mind; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Meunjohn, N.; Armstrong, A. Transformational leadership: The influence of culture on the leadership behaviours of expatriate managers. Int. J. Bus. Inf. 2007, 2, 265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.K.; Lee, Y. Assessment of Cultural Dimensions, Leadership Behaviours and Leadership Self-Efficacy: Examination of Multinational Corporations in Taiwan. 2012. Available online: http://ipedr.com/vol28/38-ICEMM2012-G00010.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Developing Transformational Leadership: 1992 and Beyond. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1992, 4, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzes, J.; Posner, B. The Leadership Challenge, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, R.J.; Waters, T.; McNulty, B.A. School Leadership that Works: From Research to Results; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandra, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, M.L.; Witziers, B.; Sleegers, P. The impact of school leadership on school level factors: Validation of a causal model. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2007, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.I.; Bass, B.M.; Sosik, J.J. Bridging leadership and culture: A theoretical consideration of transformational leadership and collectivistic cultures. J. Leadersh. Stud. 1995, 2, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, P. International and cross-cultural leadership. In Handbook for International Management Research; Punnett, B.J., Shenkar, O., Eds.; Blackwell Publisher: Malden, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 267–349. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Perttula, K.H.; Xin, K. Traditionality matters: An examination of the effectiveness of transformational leadership in the United States and Taiwan. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Does the transactional—Transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergeneli, A.; Gohar, R.; Temirbekova, Z. Transformational leadership: Its relationship to culture value dimensions. Int. J. Int. Relat. 2007, 31, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, R.; Curphy, G.J.; Hogan, J. What we know about leadership: Effectiveness and personality. Am. Psychol. 1994, 49, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, Y.; Alavi, M. Emergent leadership in virtual teams: What do emergent leaders do? Inf. Organ. 2004, 14, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier, S.D. Emergent Leadership is Focused at the Individual Level, and Is Derived from the Perceptions of Others as They Relate to a Single Person. 2012. Available online: https://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3275&context=etd (accessed on 21 February 2018).

- Carte, T.A.; Schwarzkopf, A.B.; Wang, N. Emergent Leadership: Gender and Culture the Case of Sri Lanka. 2010. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d882/9fddb56547f88cc64e070d685a8fe56cfa86.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2018).

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J. Gender and the emergence of leaders: A meta-analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 685–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.E.; Dologite, D.G. The role of computer support tools and gender composition in innovative information system idea generation in small groups. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2000, 16, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, B.L.; Shapiro, D.L. The impact of team member’s cultural values on productivity, cooperation and empowerment in self-managing work teams. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1997, 32, 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Koenig, M. Social Role Theory of Sex Differences and Similarities: Implications for prosocial behaviour. In Sex Differences and Similarities in Communication; Dindia, K., Canary, D.J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. (Eds.) Leadership, Culture, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P. The Political Dichotomy of School Leadership in the Caribbean: A multi-lens look. In School Leadership in the Caribbean: Perceptions, Practices, Paradigms; Miller, P., Ed.; Symposium Books Limited: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muhr, S.L. Caught in the gendered machine: On the masculine and feminine in cyborg relationship. Gender Work Organ. 2011, 8, 338–357. [Google Scholar]

- Rayyan, M. Jordanian women’s leadership styles in the lens of their masculinity/femininity value orientation. J. Transnatl. Manag. 2016, 21, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissessar, C.S. Correlation of female Trinidadians, Bermudians, Sri-Lankans’ feminist identity development and self-esteem: Reflection of social role theory. Adv. Women Leadersh. Online J. 2013, 33, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, A.; Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Naihua, D.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar]

- Welman, J.; Kruger, S. Research Methodology for the Business and Administrative Sciences; International Thompson: Johannesburg, South Africa, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, A. IPA and science: A response to Jonathan Smith. J. Phenomenol. Psychol. 2011, 42, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative Research, 6th ed.; Pearson: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Doing Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.D.; Dunlap, E.; Benoit, E. Structured Qualitative Research: Organizing “Mountains of Words” for Data Analysis, both Qualitative and Quantitative. 2010. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2838205/ (accessed on 21 February 2018).

- Leithwood, K.; Riehl, C. What We Know about Successful School Leadership. Taskforce on Research in Educational Leadership; Laboratory for Student Success, Temple University: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).