Music Education for All: The raison d’être of Music Schools

Abstract

:1. Introduction

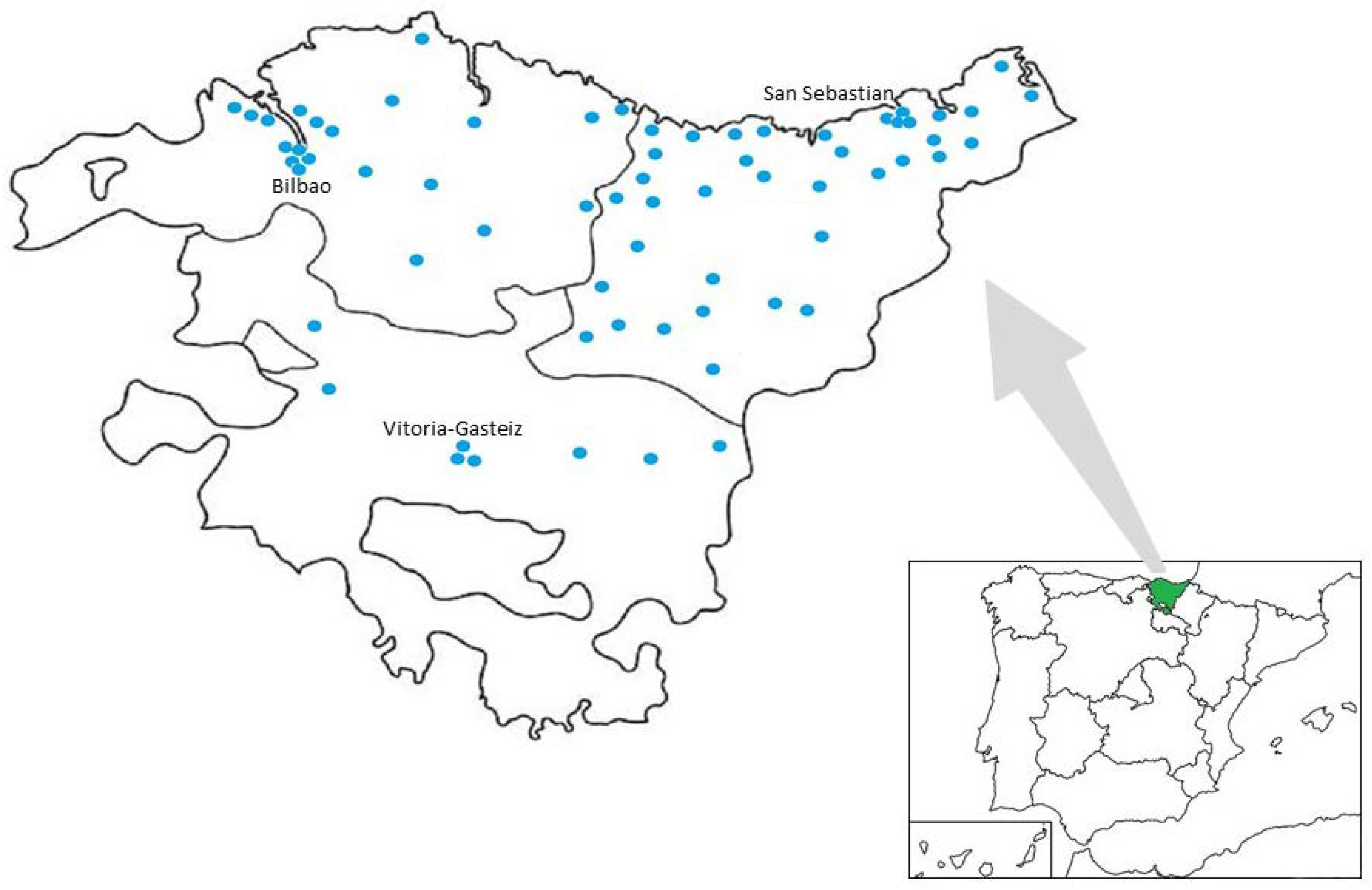

1.1. Music Education in the Basque Country

1.2. Basic Questions

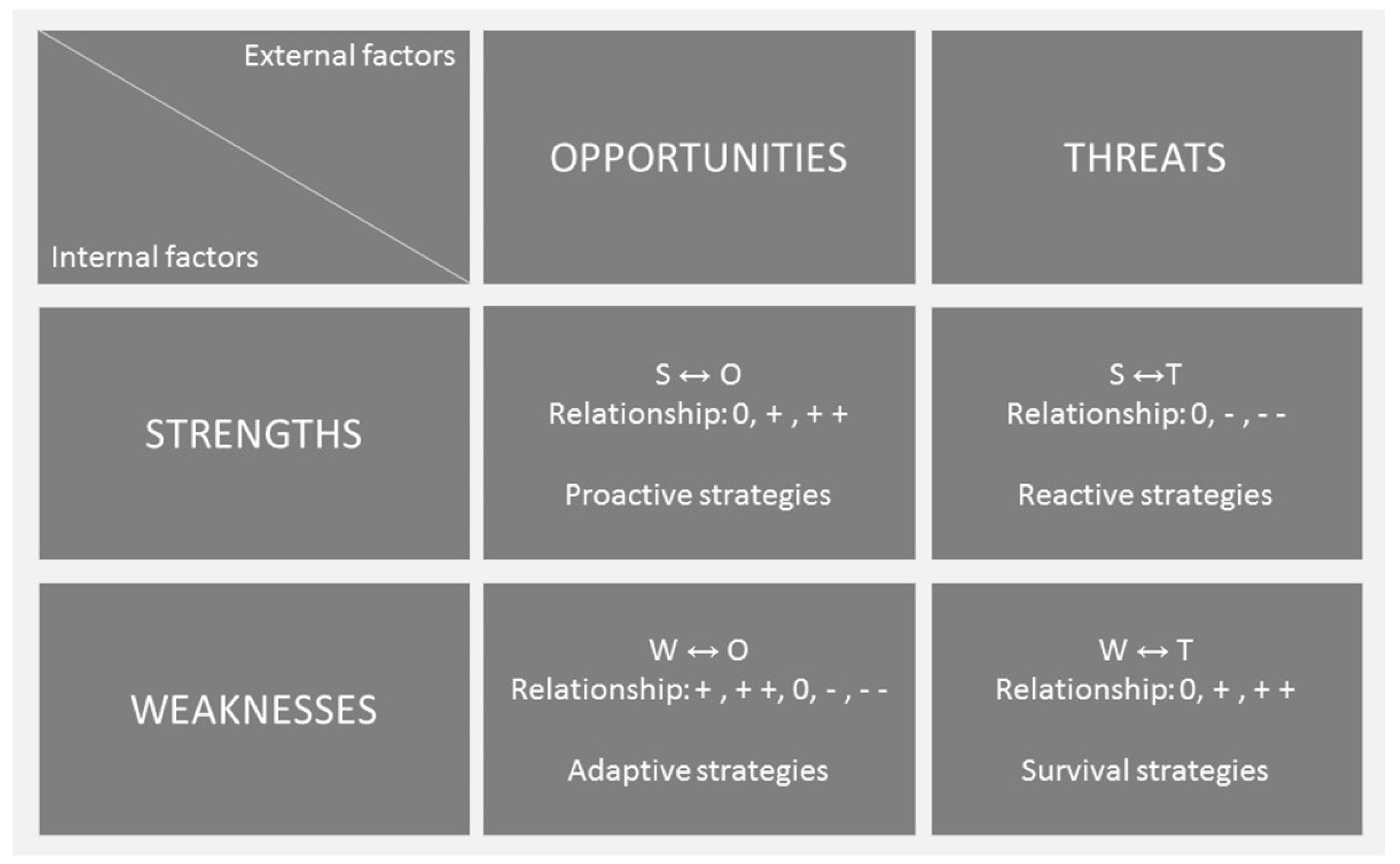

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the music school as a teaching model for specialised music education? Here, we are interested in exploring which specific aspects of these schools can be considered their strong points and which their weak points, in order to then either foster or mitigate these aspects accordingly.

- What are the opportunities music schools must take advantage of and the threats they must address in order to ensure their success? Here, the aim is to identify situations which foster the consolidation and effective running of the schools, as well as any circumstances which may prevent them from achieving their objectives, again with the aim of then either enhancing or mitigating those aspects accordingly.

- Can music schools respond and adapt to the particular circumstances of the moment? We are mainly interested in determining which elements of these schools may promote or limit their ability to adapt to the needs and demands of today’s society.

2. Method

3. Results

3.1. Internal Factors

3.2. External Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Teachers

...in small schools having the right kind of teacher is essential. What is the teacher capable of? Being versatile is key. Teachers need to have a certain set of characteristics, not only as regards qualifications, but also in relation to whether or not they like their job and are motivated and enthusiastic. When you have teachers like this, many different opportunities arise.(Music school 38)

4.2. Location of the Schools

4.3. Organisation of the Educational Process

...for instrumental classes, we have a syllabus which adapts to each student's individual pace, abilities and interests. It’s completely tailor-made ... the aim is to bring out the best in every student.(Music school 39)

...we adapt to all circumstances. We are open to everything... We usually offer a range of different mini courses in addition to the main ones...(Music school 20)

...We have a fairly broad offer. We have students of all ages, from 4 to 70. Yes, we cover all age groups.(Music school 24)

4.4. Sociocultural Aspects

...the music school is very well thought of in the town, because we organise many events out in the streets and always participate in practically everything. I think that, from the outside, we are very well thought of.(Music school 61)

...Yes, I believe it's necessary, because by participating in the cultural life of the town we attach value to the idea of leaning music. I mean, we attach value to what we are doing, to what people are learning here, and this pays off...we are also helping to generate a musical culture, as well as a culture of participation, and I think that benefits society in general.(Music school 5)

4.5. Funding

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Guide for the Semi-Structured Interview

References

- Coombs, P.H.; Ahmed, M. Attacking Rural Poverty: How Non-Formal Education Can Help; The Jhons Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA; London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Bamford, A. Arts and Cultural Education in Norway 2010–2011; University of Nordland, Nasjonaltsenter for Kunstogkultur I Oplæringen: Bodø, Norway, 2011; Available online: http://www.kunstkultursenteret.no/sites/k/kunstkultursenteret.no/files/8cd9198d7e338e77556df2ff766a160f.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Frommelt, J.; Heinz, P.; von Gutzeit, R.; Vogt, L. (Eds.) Music Schools in Europe; Schott Musik International: Mainz, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cabedo-Mas, A.; Díaz-Gómez, M. Positive musical experiences in education: Music as a social praxis. Music Educ. Res. 2013, 15, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabedo-Mas, A.; Díaz-Gómez, M. Music education for the improvement of coexistence in and beyond the classroom: A study based on the consultation of experts. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2016, 22, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusinek, G. Disaffected learners and school musical culture: An opportunity for inclusion. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 2008, 30, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, S. The power of music: Its impact on the intellectual, social and personal development of children and young people. Int. J. Music Educ. 2010, 28, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Huerta, M.C.; Kubacka, K. Fostering social and emotional skills for well-being and social progress. Eur. J. Educ. 2015, 50, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southgate, D.E.; Roscigno, V.J. The impact of music on childhood and adolescent achievement. Soc. Sci. Q. 2009, 90, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, S.E. What is music education for? Understanding and fostering routes into lifelong musical engagement. Music Educ. Res. 2016, 19, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Hafteck, L.; Schraer-Joiner, L. The engagement in musical activities of young children with varied hearing abilities. Music Educ. Res. 2011, 13, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delalande, F.; Cornara, S. Sound explorations from the ages of 10 to 37 months: The ontogenesis of musical conducts. Music Educ. Res. 2010, 12, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S. Collaboration between 3- and 4-year-olds in self-initiated play on instruments. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2008, 47, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, M.V.; Hernández, J.R.; Hernández, J.A.; Cózar, R. Formación en valores en educación infantil a través de la música. Eufonía Didáctica de la música 2015, 63, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gardikiotis, A.; Baltzis, A. ‘Rock music for myself and justice to the world’: Musical identity, values, and music preferences. Psychol. Music 2012, 40, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabé Villodre, M.D.M. Prácticas musicales para personas mayores: Aprendizaje y terapia. Ensayos Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete 2013, 28, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, T.; Minichiello, V. The meaning of music in the lives of older people. A qualitative study. Psychol. Music 2005, 33, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prickett, C.A. Music and the special challenges of aging: A new frontier. Int. J. Music Educ. Orig. Ser. 1998, 31, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, P. Intergenerational music making: A phenomenological study of three older Australians making music with children. J. Res. Music Educ. 2012, 59, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabedo, A. La música comunitaria como modelo de educación, participación e integración social. Conociendo Comusitària: ‘Arte para la construcción social’. Eufonía Didáctica de la Música 2014, 60, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J.A.; Mota, G.; Cruz, A.I. O Projeto Orquestra Geração. A duplicidade de um evento musical/social. Sociologia Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto 2017, 33, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbel, N.; Díaz, M. Educación formal y no formal. Un punto de encuentro en educación musical. Aula Abierta 2014, 42, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Coronado, M.; Vázquez, M. Guía de las Escuelas Municipales de Música; Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias (FEMP)/Ministerio de Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2010; Available online: http://femp.femp.es/files/566-1000-archivo/GuiaEscuelasMunicipalesDeMusica FEMP.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2018).

- Kenny, A. Mapping the context: Insights and issues from local government development of music communities. Br. J. Music Educ. 2011, 28, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztambide-Fernández, R.A. Musicking in the city: Reconceptualizing urban music education as cultural practice. Action Crit. Theory Music Educ. 2011, 10, 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de la Iglesia, R. A modo de prólogo. Peinando el viento: Cuando la pedagogía acaricia la gestión cultural. In Acción Pedagógica en Organizaciones Artísticas y Culturales; Gómez de la Iglesia, R., Ed.; Grupo Xabide: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2007; pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dudt, S. From Seoul to Bonn: A journey through international and European music education policies. In Listen Out: International Perspectives on Music Education; Harrison, C., Hennessy, S., Eds.; NAME Publications: Matlock, UK, 2012; pp. 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Riediger, M.; Eicker, G.; Koops, G. Music Schools in Europe; European Music School Union: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Available online: http://www.musicschoolunion.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/101115_EM_publicatie_EMU_2010_digitaal.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Heimonen, M. Music and arts schools. Extra-curricular music education: A comparative study. Action Crit. Theory Music Educ. 2004, 3, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Heimonen, M. Justifying the right to music education. Philos. Music Educ. Rev. 2006, 14, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchernoff, E. Music Schools in Europe; Association Européenne des Conservatoires, Académies de Musique et Musikhochschulen [AEC]: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; Available online: https://www.aec-music.eu/publications/music-schools-in-europe (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Decreto 289/1992, de 27 de Octubre, por el que se Regulan las Normas Básicas para la Creación y Funcionamiento de las Escuelas de Música en el País Vasco [Decree 289/1992 of 27 October, Regulating the Basic Norms for the Creation and Functioning of Music Schools in the Basque Country]. Official Basque Country Gazette No. 1, of 4 January 1993. Available online: https://www.euskadi.eus/y22-bopv/es/bopv2/datos/1993/01/s93¬_0001a.shtml (accessed on 17 January 2018).

- Orden de 28 de Septiembre de 1993, del Consejero de Educación, Universidades e Investigación, por la que se Convocan Subvenciones a los Centros de Enseñanzas Musicales [Order of 28 September of 1993 Establishing a Subsidy Programme for Music schools]. Official Basque Country Gazette No. 217, of 11 November 1993. Available online: https://www.euskadi.eus/y22-bopv/es/bopv2/datos/1993/11/9303594a.shtml (accessed on 17 January 2018).

- Roselló, D. Diseño y Evaluación de Proyectos Culturales; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weihrich, H. The TOWS matrix—A tool for situational analysis. Long Range Plan. 1982, 15, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, R.G. Strategic development and SWOT analysis at the University of Warwick. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 152, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.; Minocha, S.; Schneider, C. The strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of using social software in higher and further education teaching and learning. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2010, 26, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinesse-Demel, J. Learning Regions in Germany. Eur. J. Educ. 2010, 45, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Music School Union [EMU]. EMU 2015. Statistical Information about the European Music School Union; European Music School Union: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Available online: http://www.musicschoolunion.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/EMU-Statistics-2015-08.09.2017.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2018).

| Internal Factors | Strength (%) | Weakness (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Size and scope of school | 31.34 | |

| Location and equipment | ||

| 64.17 | 4.48 |

| 46.26 | 43.28 |

| Organisation of the educational process | 77.61 | 26.87 |

| Subject areas available | 58.20 | 17.91 |

| Teaching staff | ||

| 59.70 | |

| 52.23 | |

| 50.75 | |

| Activities with pupils | 85.07 | |

| Number of pupils | 17.91 | 25.37 |

| Positive image in the community | 52.23 |

| External Factors | Opportunity (%) | Threat (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Activities with other organisations in the community | 70.15 | |

| Pupils | ||

| 61.19 | 32.84 |

| 25.37 | |

| Schools | ||

| 71.64 | |

| 56.72 | |

| Relationship with other musical organisations | 53.73 | |

| Teaching staff | ||

| 11.94 | 13.43 |

| Social impact | ||

| 17.91 | |

| 11.94 | |

| 23.88 | |

| Funding | ||

| 73.13 | |

| 34.33 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Alba, B.; Díaz-Gómez, M. Music Education for All: The raison d’être of Music Schools. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8020066

De Alba B, Díaz-Gómez M. Music Education for All: The raison d’être of Music Schools. Education Sciences. 2018; 8(2):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8020066

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Alba, Baikune, and Maravillas Díaz-Gómez. 2018. "Music Education for All: The raison d’être of Music Schools" Education Sciences 8, no. 2: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8020066

APA StyleDe Alba, B., & Díaz-Gómez, M. (2018). Music Education for All: The raison d’être of Music Schools. Education Sciences, 8(2), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8020066