Abstract

Current attempts to further diversify the professoriate signal the critical need to cultivate pathways for students to enter academia by encouraging undergraduates to pursue further graduate education. Previous research has already noted the critical importance of positive graduate education experiences in preparing future faculty. Other researchers point to the role that faculty mentors offer in cultivating students’ future aspirations to become academics themselves. Drawing on interviews from a longitudinal study with 30 undergraduates at three Hispanic Serving Institutions, this qualitative project explores how students of various racial and ethnic backgrounds make sense of the support they receive within a program (titled HSI Pathways to the Professoriate) specifically aimed at supporting students from Hispanic Serving Institutions interested in becoming faculty members. In what ways does the program’s (HSI Pathways to the Professoriate) focus on racial and ethnic identities cultivate students’ perceptions of what it means to enter academia with the goal of diversifying the professoriate? Framed by Museus’ CECE (Culturally Engagement Campus Environments) model, this paper contributes to the importance of faculty mentors working alongside students and students’ interactions with each another as critical to the meaningful engagement of culturally responsive principles. The paper concludes with suggestions for institutions interested in cultivating these principles within their faculty.

“You have to figure out ways to do things, because it’s not handed to you. You can’t be like ‘Oh, my mom is paying my tuition, I don’t have to work.’ So, if I were to think of a [Hispanic Serving Institution], I would think ‘that’s where the hustlers are.’”—Fernanda (pseudonym), participant in HSI Pathways to the Professoriate

1. Introduction

Diversifying the racial and ethnic profile of the professoriate is an increasingly important commitment for institutions of higher education. Scholars note that there is a growing need to reflect students’ growing diversity within faculty ranks. The gains in this process have been limited; in fall 2015, for example, 77% of full-time faculty at degree-granting postsecondary institutions were White, with only 3% Black faculty and 2% Hispanic faculty (I purposefully make use of the term “Hispanic” her,e in lieu of Latinx to signal the usage of this term by the National Center for Education Statistics.) [1]. Despite the limited representation of Hispanic faculty, the proportion of doctorates awarded to Hispanics has risen from 3.3% in 1994 to 6.5% in 2014 [2]. Current attempts to further diversify the professoriate signal the critical need to cultivate pathways for students to enter academia by encouraging undergraduates to pursue further graduate education. Indeed, previous research has already noted the importance of positive graduate education experiences in preparing future faculty [3]. Other researchers point to the role that faculty mentors offer in cultivating students’ future aspirations to become academics themselves [4].

This paper focuses on the emerging findings from a multi-sited institutional partnership across three Hispanic Serving Institutions and five predominantly white research universities whose primary goal is preparing undergraduate students at HSIs with aspiration of becoming faculty in the humanities and social sciences: HSI Pathways to the Professoriate. Fernanda’s reflection, above, captures how some of the thirty students in the program’s inaugural program negotiate their identities as they aspire to enter the academic profession. Specifically, the research question guiding this paper is: how do students’ narratives of their relationships with faculty mentors illustrate principles of cultural responsiveness within the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program? I focus on students’ voices to better understand their perceptions of the culturally-sustaining mentorship they receive within a program specifically designed to foster aspiring faculty within the context of Hispanic Serving Institutions. Amplifying students’ voices offer critical insights into the way institutions can ensure they are creating programs responsive to students’ assets, cultural context, and their desire to better understand the “hidden curriculum” in academic spaces [5].

The structure of the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program provides a rich context through which we can gain insights into the processes that motivate and challenge undergraduates in their aspirations to join the professoriate. In this article, I offer an overview of HSI Pathways to the Professoriate, and focus on elements of its mentorship structure that all participants receive across the three participating institutions. Specifically, I focus on how the mentorship interactions within the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate model offers promising strategies that are culturally responsive across the four domains in Museus’ Culturally Engaging Campus Environment model [6]. By demonstrating how students’ articulations of HSI Pathways to the Professoriate expand upon aspects of a collectivist cultural orientation, a humanized educational environment with engaged with proactive philosophies and holistic support, I further expand our understanding of the cultural responsiveness tenets espoused by the CECE model [7] (p. 192). Below, in Section 2.3, I describe how the CECE model functions as the conceptual model undergirding the analysis in this manuscript.

Much of the prior research on effective mentorship strategies focuses on these relationships in the context of STEM education [8,9,10]. Research focused on the mentorship of Hispanic students at the undergraduate level point to the importance of alignment between students’ and mentors’ cultural orientations [11]. Specifically, within the context of Hispanic Serving Institutions, authors like Crisp & Cruz previously noted the need for additional qualitative work exploring “how mentoring is ‘valued,’ ‘needed,’ and ‘reflected on,’ by different groups of college students, especially Hispanic students [12], (p. 241). In this respect, this article answers this call by focusing on a group of participants from HSIs, most of whom self-identify as Hispanic and/or Latinx.

A Brief Overview of Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs)

Given the specificity of the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program, this section offers an overview of the HSI designation. Hispanic Serving Institutions emerged in response to rapid demographic shifts in the nation and are defined by the federal government as institutions with at least 25% low-income Latinx students. Specifically, institutions that had originally served the majority population experienced demographic changes to their student bodies due to increases in the Latinx population on their campuses. Several of these institutions eventually achieved a critical mass of Latinxs and began to embrace their new student bodies and focus much of their efforts on retaining, supporting, and graduating Latinx students. These institutions have experienced admirable results. In 2012, HSIs enrolled nearly 56% of all Latino/a students. HSIs boast diverse faculties and staffs, provide environments that significantly enhance student learning and cultivate leadership skills, offer same-race role models, provide programs of study that challenge students, address deficiencies resulting from poor preparation in primary and secondary school, and prepare students to succeed in the workforce and in graduate and professional education. HSIs play a vital role in shaping the nation’s economy by: (a) elevating the workforce prospects of Latinxs; and (b) contributing to the presence of Latinxs in graduate school. Because HSIs enroll a substantial share of underrepresented students, many of whom might not otherwise attend college, the continuous development and success of these institutions are critical for realizing our nation’s higher education and workforce goals and for the benefit of American society [13].

One-half of all students enrolled at HSIs receive Pell Grants, compared with only 31% of all college students. These high rates of Pell Grant eligibility exist even though tuition rates at HSIs are, on average, 50% less than that of predominantly White institutions (PWIs). Students at HSIs are also more likely than those attending PWIs to have lower levels of academic preparation for college and are more apt to come from high-stress and high-poverty communities. And not surprisingly, almost 65% of all HSI students are the first in their families to attend college, compared to only 35% of students attending PWIs. Put simply, for many students, HSIs are a gateway to higher education and beyond [14].

Importantly, in addition to these commendable goals, HSIs are diverse institutions that have various cultures and have, at times, struggled to embrace this designation [15]. Indeed, by virtue of the demographic-contingency of the HSI designation, some campuses have not yet persisted from merely being “Latinx-enrolling” to “Latinx-Serving” [16,17]. Though applying García’s innovative typology of HSI organizational identities to the three HSIs in the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program is beyond the scope of this manuscript, it is nonetheless a critically important tool to remind readers that HSIs exist within a spectrum with respect to their ability to serve Latinx students. In turn, this manuscript focuses on a specific intervention across three institutions that explicitly articulates the HSI designation as a way of foregrounding programming attuned to students’ identities in their process of receiving support to succeed in future graduate aspirations.

2. Materials and Methods

The data for this manuscript emerged from the first wave of interviews in a longitudinal project with students enrolled at three Hispanic Serving Institutions conducted between June and July of 2016. All participants (n = 30) were part of HSI Pathways to the Professoriate, a multi-sited program targeting students interested in pursuing doctorate degrees in the humanities and social sciences, at the time of recording these conversations. Semi-structured interviews with these participants lasted between 30 to 60 min and focused on their experiences in the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program, including their interactions with peers, faculty mentors, and their time in a six-week summer program designed to introduce them to the structure of graduate education.

In addition to the richness of these interviews, participants’ responses were triangulated with institutional documents produced across the three participating HSIs, as well as interviews and correspondence with faculty mentors, and coordinators responsible for running the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program.

2.1. Overview of HSI Pathways to the Professoriate

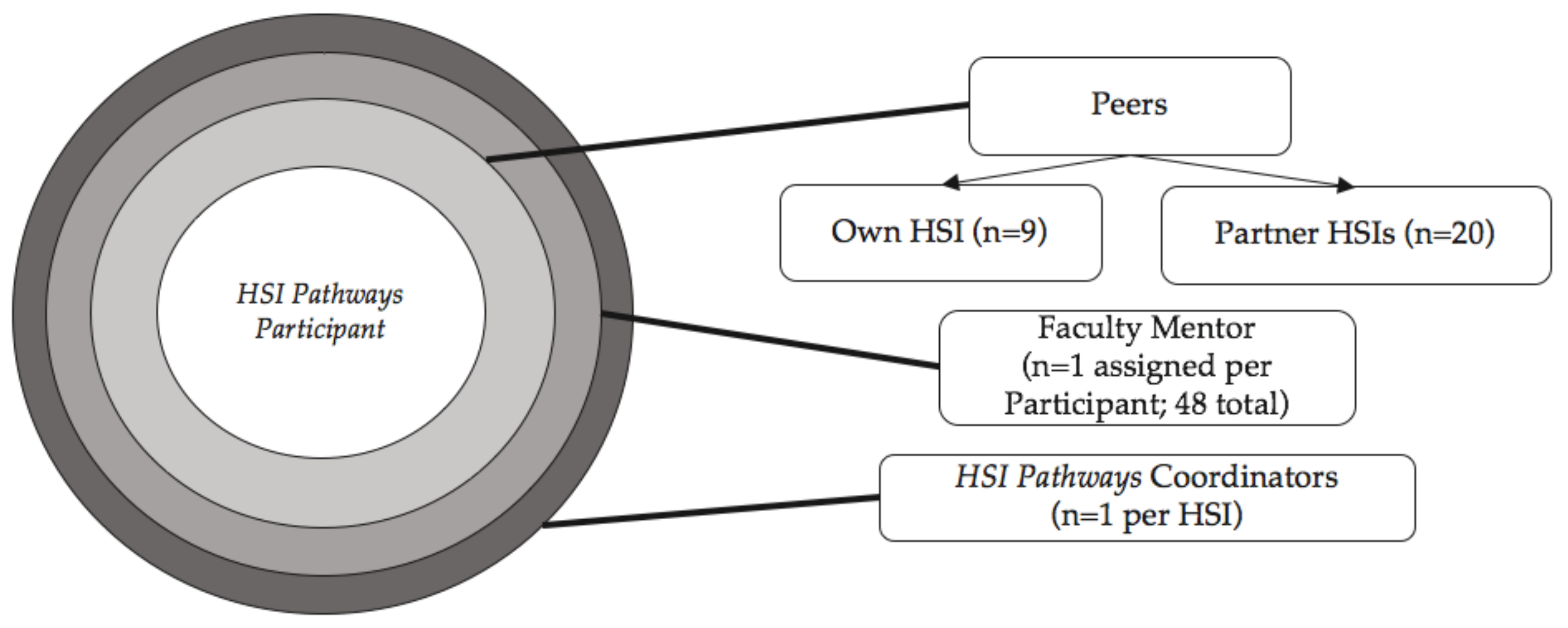

Students’ participation in the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program spans multiple years of their undergraduate education; traditionally, it begins during their junior year and lasts through their first year in graduate school. As participants enter the program, they are introduced to an ecosystem of support that encompasses their peers, some of whom are within their institution or at the other two participating Hispanic Serving Institutions. In addition to their peers, they have a designated HSI Pathways to the Professoriate mentor who is often a faculty member in the student’s intended field of further study or a related cognate field. In addition to their designated mentor, participants in HSI Pathways to the Professoriate also have access to the 48 faculty members affiliated with the program, some of whom are at one of the five participating predominantly white institutions who are also part of this program. On each campus, the program is organized by a designated individual who is also a faculty member or senior campus official. These overlapping communities form the core of participants’ HSI Pathways to the Professoriate ecosystem and contribute to their experience in the program (see Figure 1). The explicit focus of the program is to provide a robust array of resources and support to students who come from backgrounds or have identities that have largely been underrepresented in academia. Furthermore, given that HSI Pathways to the Professoriate is housed within three Hispanic Serving Institutions, it has provided an opportunity for the program to intentionally develop a space where participants actively discuss the potential issues encountered by individuals with minoritized identities in academia as part of the program’s ongoing discussions with participants. Importantly, the three HSIs participating in this program vary in their institutional profiles. Though all three institutions are four-year and public, they are spread in their geography with one each in California, Texas, and Florida, accounting for quite distinct representation of Cuban-, Mexican, and Central-American populations within their student bodies. They enroll between 20,000 to 55,000 students, most of whom are undergraduate students; however, the institution in Florida only has 57% full-time students whereas 8 in 10 students at the HSI in California are enrolled full-time. Future research can consider the relationship between these institutions’ characteristics and how the program unfolded within each HSI; the project of this manuscript, however, focuses on the specific interactions between the students and the faculty mentors.

Figure 1.

Hispanic Serving Institutions (HIS) Pathways to the Professoriate participants’ ecosystem of support.

2.2. Overview of Participants

There were ten students participating in HSI Pathways to the Professoriate at each of the three participating Hispanic Serving Institutions for a total of 30 participants in the data included in this manuscript. The median age for participants was 22 (with a range from 19 to 39 years). Twenty-one of the participants self-identified as women and nine as men. The clear majority (86%) were on some form of financial aid, and 70% of them came from houses where parents had not completed a four-year degree. All of the participants had been selected through a competitive process to participate in the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program, with the incentives of receiving ongoing one-on-one mentorship with a designated faculty member at their institution, access to mentors at other participating universities, a summer stipend to participate in a six-week long seminar, access to ongoing programming throughout the academic year, as well financial support in the preparation of their graduate school applications.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The interviews were conducted individually with each participant at a location on their campus. Participants were interviewed by the author, as well as three other members of a research team overseeing the broader longitudinal study of the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program. The conversations began with an invitation for participants to share stories from their upbringing and the experiences that participants deemed relevant to understand how they had ended up enrolling at their current institution in an effort to better acquaint ourselves. Of note, participants had already established rapport with the interviewers during virtual conversations in the months leading to the visits to their respective campuses. The interview protocols offered opportunities for participants to freely recall memorable events during their participation with the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program, with a specific focus on their interactions with peers within their cohort, their designated faculty mentor, and their impressions of the six-week summer program. The open-endedness in in the interview protocol was guided by prior research that positions interviewers and participants as dialectic interlocutors co-constructing meaning from previous social interactions [18,19]. Consistent with prior qualitative work on student success within Minority Serving Institutions, we used these open-ended conversations as an opportunity to have participants “connect a story or observation with a comment or phrase that had come up earlier in the interview.” [20] (p. 87). As students narrated their stories, we were committed to letting each participant share their histories in a way that not only enhanced our understanding of HSI Pathways to the Professoriate, but that also provided a space for authentic exchanges and disclosure [21]. Upon completion of the interviews, each interview’s audio file was transcribed in its entirety and reviewed by multiple members of the research team for accuracy and consistency. The author then formatted these files so they could be uploaded to the qualitative software, NVivo (v. 11).

Past scholarship has employed the principles of the Culturally Engaging Campus Environments model to theorize organizational behaviors at HSIs [22]. The CECE model, developed by Museus, suggests that there are specific organizational attributes illustrating an institution’s cultural relevance and cultural responsiveness [6,7]. Specifically, the model suggests that a campus’s ability to illustrate cultural familiarity, culturally relevant knowledge, cultural community service, cross-cultural engagement, and cultural validation are all attributes of a Culturally Relevant campus. It further suggests that a collectivist orientation, humanized environments, proactive philosophies, and holistic support are all emblematic of cultural responsiveness. Given that the guiding research question for this manuscript explores the relationship between students and their faculty mentors, exploring the attributes that can showcase elements of responsiveness from faculty towards students’ needs is most apt for the analysis of participants’ transcripts. Following CECE tenets, transcripts were read with specific attention to a priori codes emerging from culturally responsive strategies adopted within culturally engaging campuses [23]. As an iterative process, the coding of these transcripts enabled the author to review and synthesize the substantive ways in which students articulated their experiences in the program as consistent with the culturally responsive principles of the CECE model.

3. Results

In this section, I have thematized the elements of the mentorship that students have received from their HSI Pathways to the Professoriate faculty, coordinators and peers. Framed by the CECE tenets of cultural responsiveness, I showcase how HSI Pathways to the Professoriate, a program developed explicitly with the goals of supporting students from minoritized backgrounds, successfully integrates cultural awareness in its academic support for students.

3.1. A Collectivist Cultural Orientation by Cultivating a Sense of Familia

In answering prompts about the mentoring and support that they received, multiple participants of the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program reflected not just on the guidance offered by their faculty mentors, but also from their peers. Daniela, one of the participants, said:

“I like being able to keep going and getting things done feels very productive, and I think my mentor, is amazing. He definitely holds me to a very high standard. He wants me to succeed, so he keeps pushing me, and I really appreciate that. [HSI Pathways to the Professoriate coordinator] does the same thing. I think the other fellows are very—we want to see each other succeed—and we’re not competitive in the sense that we’re like trying to hurt each other, but we do strive to be, like, the best cohort. I think we all say that, but we definitely want that. I think we definitely feel like we’re the underdogs, and so in many respects, we are, so we push each other to be better, and it is very—it is a very great environment to be in, I think. It fosters a lot of growth.”

In Daniela’s words, what becomes clear is that the expectations to succeed came not just from her mentor and coordinator, but also from her peers. In the same vein, Fernanda, who had spoken about her institution as a home for hustlers, mentioned that the shared experiences with her peers allowed her to believe in their ability to persist despite how others at prospective graduate institutions may view them as “underdogs,” (to draw from Daniela’s description). In Fernanda’s estimation, the benefits of being in a program like HSI Pathways to the Professoriate while at an HSI derived from knowing that:

“People around me here, they know the struggle, and I don’t want to say that all Hispanics are like this, because this is not true, but just in my opinion, people here work really hard. Maybe they don’t have time, as somebody who is at an Ivy League school or another [high ranking school] to spend all their time reading and stuff, but I think people here work really hard as well, and they’re here for a reason.”

Fernanda offers insights into the solidarity that can emerge from understanding that the peers with whom she shares the experiences in HSI Pathways to the Professoriate do, in fact, understand the struggles, while also evidencing the nuance needed to avoid a totalizing narrative that would otherwise depict Hispanics as inherently knowledgeable of “the struggle”. In effect, rather than succumbing to the deficits that often accompany these narratives, Fernanda is emblematic of the way the participants in this program can cultivate a sense of familia that sustains their efforts to succeed. Indeed, all thirty participants echoed Fernanda’s sentiments by mentioning the importance of the family-like atmosphere cultivated amongst their peers, and over half of them also mentioned these sentiments in relation to their faculty mentors.

3.2. Proactive Philosophies by Anticipating Potential Hurdles

As participants recalled their conversations with their mentors, they shared insights into how they perceived their mentors as anticipating potential hurdles that they could face as they progressed through their preparation to enter academia. Mentors proactively shared these concerns with students in a way that allowed them to think through strategies that they could employ to avoid stumbling in the face of these potential developments. For example, Isaías had shared his concerns about moving far away from his family. Though this concern had been echoed by over half of the participants, his history with personal dis/abilities had amplified these hesitations. As he shared, “if the only option for college meant going somewhere very far away, I was not sure I would have wanted to do that because I wasn’t—at that point—comfortable with taking that leap. But, as [his HSI Pathways to the Professoriate coordinator] and many of the other mentors have tried to tell us, we are much more attractive as a potential faculty member if you [sic] leave the state that you are in, and I’ve been slowly coming to terms with that.” The conversations in which Isaías had engaged had exposed him to the potential shortcomings of limiting his future educational trajectories to the region where he had grown up. In doing so, his faculty members proactively introduced him to the realities of having to make sense of insidious “academic caste system” that can mediate people’s experiences in their future job searches [24]. Though this is a difficult reality to confront, the faculty member’s willingness to introduce these conversations to HSI Pathways to the Professoriate participants better prepare them to face the challenges ahead.

3.3. Holistic Support and and a Humanized Environment by Listening to Students’ Needs

In the same vein that all members of the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program strove to cultivate a familial sense by holding each other to high standards, participants also shared how they felt supported beyond their academic preparation. One of Fernanda’s specific stories narrates how her HSI Pathways to the Professoriate familia came together to model how to think beyond the binary of mothering and academic pursuits:

“Like I said, I have a lot of support from [HSI Pathways to the Professoriate coordinator], who has been really supportive … I mean even when we went to [another city for an academic conference], it was my son’s birthday weekend. I was like ‘these are the choices I’m going to have to make. I felt really guilty. I’m going to choose the academic conference over my son’s birthday’. And so she [her HSI Pathways to the Professoriate coordinator] was like ‘No, you don’t have to do that. Bring him.’”

Fernanda went on to share that her HSI Pathways to the Professoriate coordinator brought along her partner so her child had proper childcare while she attended her academic sessions with her peers. In opening up to express her own concerns, Fernanda was able to establish a sense of support by realizing that she, too, could thrive in her pursuit of further graduate education. Later, in our conversation, she offered that finding the shared “cultural background,” with her academic advisor allowed her to see herself succeeding in her future: “even though she didn’t have a child, she had to support her parents. She had to, and so just seeing that she found a way to make it through grad school and have a job—that’s helpful, just knowing that somebody else has done it. I’m just trusting that I can figure it out too”.

For Fernanda, the ability to see her (future) self-reflected in her mentor was a particularly meaningful moment. Yet, sometimes, the process of finding a sense of shared humanity in meaningful mentorship interactions does not require mentors to reflect students’ selves. Rather, in producing an environment propitious for participants’ success in the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program, mentors, and participants offer meaningful insights into the processes of understanding that being part of a cohort must not be construed with understanding that all participants have the same needs. By embracing the complexity of each participants’ life stories, members of the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program can offer the specific support that every member needs.

Xenia, another participant, aptly captured the uncertainty of her needs with a particularly fitting metaphor:

“And I think sometimes when you don’t have a mentor, you feel like you’re a sitting duck. You’re just there floating. Everybody else is, all of the other ducks are going in front of you and you just feel like you’re floating and you’re just like ‘I don’t know exactly where I’m going or what I want’. My mentor made me feel better about not knowing what I wanted precisely but she’s like ‘Well you have to go in that direction’. So, yeah, she was really helpful.”

At times when students experience a sense of being adrift like Xenia’s duck, the holistic support that mentors offer is maximized when students are able to share the vulnerabilities of uncertainty. Xenia’s disclosure of feeling like she was merely floating was assuaged by having a mentor with whom she could share her lingering concerns and who could reflect suggestions of avenues that she could consider undertaking. In effect, well over two thirds of the participants discussed the support networks emerging from their interactions with their mentors and peers as anchors helping them navigate the terrain of preparing for their future graduate education.

4. Discussion

The CECE model’s principles of “cultural responsiveness” extend to the campus environment in which students engage themselves. Most of these principles apply to the (in)actions of faculty and staff that can deeply affect a student’s sense of belonging (and, consequently, future success) in academia. In documenting how the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program can serve as a specific case study of a culturally responsive program, we can extend the tenets of cultural responsiveness within the CECE model to also encompass peer-to-peer interactions. As evidenced by the voices of the participants in this program, many of them invoked the importance of their peers as (in)valuable members of the individuals who offered encouragement and mentorship throughout the process of participating in this program. By noting the role that peers have as part of the mentorship ecosystem in which students participate, these students’ narratives offer helpful considerations for future research and practice.

4.1. Recommendations for Research

The analysis in this article focused on the “cultural responsiveness” elements of the CECE model. Further work, however, can extend this analysis by also considering the “cultural relevance”, defined as the ways in which campus environments are not just reactive but also reflective of students’ identities and backgrounds [7]. As a longitudinal project, there is also ample room for future work to consider the varied perceptions of the mentoring relationships between faculty and students, particularly with respect to the cultural responsiveness of models that are embedded within Hispanic Serving Institutions. Furthermore, the construction of the sense of an internal familia within an institutional program also opens avenues for further inquiry that can interrogate how students reconcile their relationships with their biological families and emerging kinship models of support constructed through students’ academic engagement in pre-doctoral programs like HSI Pathways to the Professoriate. Prior work demonstrates the critical importance of students’ families in their academic success, yet there is room for further work to also consider how students synthesize these various families of support.

4.2. Recommendations for Practice

Centering students’ narratives of their experiences in the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program underscores the potential gains of embedding faculty research mentorship in the context of a cohort model with peers that share similar academic and professional goals. As these participants demonstrate, there is a fruitful opportunity to model a spirit of familia and generosity that can be cultivated early in individual’s introduction to their potential lives within academic professions. At a time when other scholars lament the rise of cutthroat academic careerism, engaging a programmatic structure that amplifies the tenets of cultural responsiveness serves as a welcome intervention [25]. Though generalizable inferences are beyond the scope of the qualitative methodologies used in this manuscript, other practitioners who oversee the development of pre-doctoral programs for undergraduates are well-served in considering the relevance of fostering a cohort that is guided by principles of openness with one another and with their mentors. These practices extend beyond the conversations shared by mentors and participants and can also be embedded within the structure of the programs in which these individuals interact. For example, at one of the sites of the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate six-week summer program, the coordinator had established a series of permanent stations where students could write letters of support to one another, express gratitude for guest speakers or mentors, or unwind with relaxation tools. The resourcefulness of the coordinator and responsiveness to students’ needs paved the way for these participants to not merely hustle for survival, but to thrive in community.

5. Conclusions

Enhancing cultural responsiveness must be embedded within mentorship interactions with students vying to participate in the diversification of the professoriate. Mentors and students within the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate model promising practices and relationships that show how centering students’ experiences beyond their academic formation are central to enhancing students’ desire to further their academic formation. Indeed, programs that center students’ identities as a core component of its programming can steward a more holistic understanding of how we are to support those will become the future of our academic profession.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Marybeth Gasman, Paola Esmieu, and Andrew Martinez for their collaborative work in documenting these interviews and undertaking the research efforts that enabled the writing of this article. The author also acknowledges the 30 students whose voices and wisdom structured the insights shared in this paper, as well as their faculty mentors and program coordinators to the HSI Pathways to the Professoriate program. The author also thanks the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for providing the funds enabling the development of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. The Condition of Education. 2017. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=61 (accessed on 28 January 2018).

- National Science Foundation. Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2014. 2015. Available online: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2016/nsf16300/ (accessed on 28 January 2018).

- Austin, A.E. Preparing the Next Generation of Faculty: Graduate School as Socialization to the Academic Career. J. High. Educ. 2002, 73, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, V.; Pifer, M.; Lunsford, L.; Greer, J.; Ihas, D. Faculty as Mentors in Undergraduate Research, Scholarship, and Creative Work: Motivating and Inhibiting Factors. Mentor. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 2015, 23, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, E.; Romero, M. “The department is very male, very white, very old, and very conservative”: The functioning of the hidden curriculum in graduate sociology departments. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1998, 68, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museus, S.D. The Culturally Engaging Campus Environments (CECE) Model: A New Theory of Success among Racially Diverse College Student Populations. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 189–227. ISBN 978-94-017-8004-9. [Google Scholar]

- Museus, S.D.; Yi, V.; Saelua, N. The Impact of Culturally Engaging Campus Environments on Sense of Belonging. Rev. High. Educ. 2017, 40, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byars-Winston, A.M.; Branchaw, J.; Pfund, C.; Leverett, P.; Newton, J. Culturally Diverse Undergraduate Researchers’ Academic Outcomes and Perceptions of Their Research Mentoring Relationships. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2015, 37, 2533–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, E.T.; Holmes, R.M.; Wirkus, S.A. Transforming the Undergraduate Research Experience through Sustained Mentoring: Creating a Strong Support Network and a Collaborative Learning Environment. New Dir. High. Educ. 2015, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpi, A.; Ronan, D.M.; Falconer, H.M.; Lents, N.H. Cultivating Minority Scientists: Undergraduate Research Increases Self-Efficacy and Career Ambitions for Underrepresented Students in STEM. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2017, 54, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.B.; Yang, Y.; Dicke-Bohmann, A.K. What Do Hispanic Students Want in a Mentor? A Model of Protégé Cultural Orientation, Mentorship Expectations, and Performance. J. Hisp. High. Educ. 2014, 13, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, G.; Cruz, I. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of a Measure of “Mentoring” Among Undergraduate Students Attending a Hispanic Serving Institution. J. Hisp. High. Educ. 2010, 9, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, A.-M.; Hurtado, S.; Galdeano, E.C. Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Advancing Research and Transformative Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-317-60169-2. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, C. Educating a Diverse Nation; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-674-42549-1. [Google Scholar]

- Doran, E.; Medina, Ø. The Intentional and the Grassroots Hispanic-Serving Institutions: A Critical History of Two Universities. Assoc. Mex. Am. Educ. J. 2018, 11, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.A. What Does it Mean to be Latinx-serving? Testing the Utility of the Typology of HSI Organizational Identities. Assoc. Mex. Am. Educ. J. 2018, 11, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.A. Defined by Outcomes or Culture? Constructing an Organizational Identity for Hispanic-Serving Institutions. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 54, 111S–134S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, R.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theories and Methods, 5th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-205-48293-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Dominance through Interviews and Dialogues. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 480–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasman, M.; Ginsberg, A.; Castro Samayoa, A. Minority Serving Institutions: Incubators for Teachers of Color. Teach. Educ. 2017, 52, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, K. Reflective Interviewing: A Guide to Theory and Practice; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4462-4469-2. [Google Scholar]

- García, G.A. Complicating a Latina/o-serving Identity at a Hispanic Serving Institution. Rev. High. Educ. 2016, 40, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4739-0248-0. [Google Scholar]

- Burris, V. The Academic Caste System: Prestige Hierarchies in PhD Exchange Networks. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2004, 69, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P. Survival Guide Advice and the Spirit of Academic Entrepreneurship: Why Graduate Students Will Never Just Take Your Word for It. Workplace 2013, 14, 25. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).