1. Introduction

Job satisfaction is increasingly imperative in the working environment and has been associated with numerous factors, including efficiency, productivity, non-attendance, turnover, and so on. Employees’ job satisfaction is indispensable in confronting the dynamic and ever-increasing complications and challenges of maintaining profitability of an organization by keeping their employees regularly engaged and inspired [

1]. The occupation of school head has become more demanding and intense. The importance of job satisfaction has been recognized as increasingly dire in educational settings because both head teachers and educators are managing the future of the society in which they work [

2]. Therefore, the responsibilities of a school head are very crucial to ensure the successful performance of school by ensuring a favorable climate, provision of adequate resources, and ensuring strong relationships and satisfactory performance of students [

3,

4,

5,

6]. School heads cannot accomplish their duties and responsibilities successfully until they are satisfied and secure in a workplace. Leaders with problems can lead to various negative and undesirable consequences for organizations and its workforce, which negatively affect the overall organizational achievements. Therefore, job satisfaction is the dominant variable because it is directly related to organizational productivity and individuals’ prosperity.

The concept of job satisfaction was initially introduced in the Hawthorne investigations during the 1920s and 1930s by Elton Mayo at the Hawthorne plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago. Job satisfaction is a multifaceted and complex variable that can describe different things to different people. Job satisfaction is an employee’s feeling of attainment and accomplishment at work. It is generally perceived to be directly related to efficiency and individual’s prosperity. Job satisfaction is an undertaking one appreciates, enjoys, performs it effectively and being rewarded for one’s efforts. Job satisfaction also suggests excitement and pleasure with one’s work. Job satisfaction is the fundamental that contributes to appreciation, advancement, income, and the accomplishment of different goals that cause feeling of satisfaction [

7]. Job satisfaction is also defined as the end condition of feeling, the feeling that is encountered after completing a task and may be negative or positive depending on the outcomes of the errand endeavored [

8]. Likewise, job satisfaction is the set of emotions and beliefs that individuals have about their current job. Individuals’ level of job satisfaction can range from extraordinary satisfaction to outrageous disappointment. Individuals also can have different views about different facets of their professions, for example, the nature of work they do, their colleagues, managers or subordinates and their compensation [

9]. Job satisfaction is a greater amount of a disposition, and inside state. It might, for example, be associated with an individual’s emotions of attainment having quantitative or qualitative nature [

10]. Job satisfaction is one of the most grounded indicators of esteemed organizational productivity, organizational responsibility, and commitment [

11]. Job satisfaction is viewed as a worker’s demeanor towards employment and the employment circumstances [

12].

A number of research studies have been carried out to compare the job satisfaction of male and female individuals in different contexts [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. In some research studies, no significant difference was found between the job satisfaction of males and females while in many research studies it was found that males are more satisfied with their employment as compared to females. On the other hand, some research studies have found contrary outcomes in which they found that females are more satisfied with their job than males. Rast and Tourani [

13] found that employees were moderately satisfied with their job and there was no significant difference between the job satisfaction of male and female employees. Mumtaz, Suleman and Ahmad [

14] concluded that on the whole, higher secondary-school heads were found satisfied intrinsically and extrinsically with their job position except for five dimensions i.e., ability utilization, supervision (HR), supervision (technical), education policies and working conditions. Furthermore, no significant difference was found between male and female higher secondary-school heads’ satisfaction with regard to intrinsic and extrinsic dimensions of their job except for ability utilization and compensation. Similarly, Donohue and Heywood [

15] found no significant difference between the job satisfaction of male and female individuals. Oshagbemi [

24] investigated that gender has no substantial effect on job satisfaction. Likewise, Koyuncu, Burke, and Fiksenbaum [

16] reported that there was no significant contrast in the job satisfaction of male and female instructors. Ali and Akhter [

17] expressed that there was no huge distinction between the perspectives of male and female employees with respect to job satisfaction. On the other hand, Ghazi [

18] found that female head teachers were more satisfied than males. In the same way, Mahmood [

19] also found that female respondents were more satisfied with their employment than male respondents. Ali et al. [

20] also concluded that there was a noteworthy contrast of employment satisfaction between male and female secondary-school teachers. Similalry, Brogan [

25] expressed that there was a substantial contrast between the job satisfaction of male and female principals; male principals were more satisfied than females.

1.1. Theories and Models of Job Satisfaction

1.1.1. Frederick Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory

Frederick Hertzberg’s two-factor theory (also called Motivator Hygiene Theory) explains satisfaction and inspiration in the workplace. The theory states that satisfaction and dissatisfaction are caused by many variables i.e., motivational or inspirational and cleanliness factors etc. Motivational factors are those facets of the employment that individuals need to accomplish and enrich with satisfaction. These variables are believed to be intrinsic for employment or work accomplishment. Hygiene factors are composed of workplace facets i.e., compensation, organization policies, supervisory practices, and other working situations [

26]. Motivators or intrinsic (satisfier) variables are associated with the real execution of the work, or the content of the job. The motivators are the internal factors of employment that wish the workers to progress toward better accomplishments and contribute to job satisfaction and higher inspiration [

27]. According to the theory, motivators and hygiene factors are non-exclusive. Satisfaction and dissatisfaction cannot be regarded as the inverse closures of one continuum. Subsequently, an increase in the level of employment fulfillment does not infer a diminishing in employment dissatisfaction as there are different factors influencing satisfaction and dissatisfaction among the individuals [

28].

Intrinsic motivators i.e., responsibility, the though

t-provoking nature of employment, and accomplishment are motivators which originate from inside a person [

29]. The existence of intrinsic motivators contributes to job satisfaction, yet their non-existence will not contribute to job dissatisfaction [

30]. In a teaching career, intrinsic factors play a rewarding role in boosting people to join a stated occupation [

31]. To ensure individuals’ encouragement, fulfillment and inspiration about their employments, Herzberg and his colleagues guaranteed that the emphasis ought to be on variables connected with the nature of work, or outcomes directly achieved from the work, e.g., work itself, for self-improvement, recognition, accountability, and accomplishment. Therefore, fulfillment with the intrinsic facets of the job is long-lasting and, subsequently, enables individuals to keep their motivation for a long time [

32].

1.1.2. Hierarchy of Need Theory

Maslow [

33] was a renowned figure in the field of psychology. He was psychologist by occupation and believes that in the mission to satisfy the demands and requirements, people act and exhibit in a specific way. Humans attain fulfillment only when their needs are satisfied. His theory has three suppositions i.e., human needs never end, when one need is satisfied, the next hierarch of needs to be satisfied. Ultimately human needs can be divided into different levels depending the significance and when the level of need is satisfied, the next level of needs has to be satisfied to determine satisfaction [

34]. Maslow’s hierarchical model of human needs can be utilized to identify the factors manipulating job satisfaction. The hierarchy of needs recognizes five distinctive levels of individual needs such as physiological needs, social needs, esteem needs, self-actualization needs and security needs [

35].

Maslow’s need hierarchy outlines origination of individuals fulfilling their needs in a predefined order from bottom to top i.e., individuals are propelled to fulfill the lower needs before they attempt to fulfill the higher needs. Once a need is fulfilled, it is no more a powerful motivator. It is simply after the physiological and safety needs are practically fulfilled that the higher needs (social, esteem, and self-actualization) get to be the distinctly dominant concern [

36]. Utilizing Maslow’s theory, supervisors can persuade and guarantee job satisfaction in their workers by ensuring that every individual’s need is fulfilled. Fulfillment of such needs can be possible through offering appropriate rewards. For instance, supervisors or mangers can fulfill workers’ physiological needs through arrangement of accommodation and a staff cafeteria. Likewise, workers’ security needs can be fulfilled through guaranteeing that workers are given compensation, retirement pension and medical facilities [

35]. For social needs, managers can assure workers’ job satisfaction by empowering social association among the workers. Managers can plan challenging jobs, assign duties, and strengthen participation in decision making to fulfill workers’ esteem needs. The needs for self-actualization can be fulfilled through the arrangement of executive training, arrangement of difficulties and encouraging creativity. Managers can also keep up job satisfaction in their workers by ensuring that a satisfied need is persistently met [

34].

1.1.3. The Expectancy Theory

Vroom was the first scholar who introduced the Expectancy Theory [

10,

37,

38]. According to this theory, individuals possess set of goals (outcomes) in different ways, and can be inspired and boosted provided they have certain expectations. Based on their former experiences, individuals tend to create assumptions with respect to the level of their job performance. Workers also create assumptions in regard to performance related results. They tend to lean toward specific results over others. Therefore, before joining employment, they consider what they need to perform to get compensation, and how much the reward means to them [

39]. There are different components that hinder an extraordinary performance, for instance, an individual’s personality, abilities, knowledge, or the manager’s recognitions. Underqualified and unskillful individuals will not be suitable in their performance, essentially by attempting. Vroom’s Expectancy Theory is also called the Valence or the Valence-Instrumentality-Expectancy (VIE) Theory [

34]. Expectancy is the level of an individual’s assurance that the choice of an alternate option will definitely contribute to desired outcomes [

40].

Valence is the feeling individuals have about particular outcomes and is referred to as expected satisfaction from expected outcomes [

10]. Instrumentality is an outcome-outcome relationship and is based on the belief that if the individuals perform one thing, then it will lead to another [

37]. It is a belief of probability of the first outcome, outstanding job performance, achieving the second outcome and reward [

41]. The fundamental principle of the Expectancy Theory is the perception of an individual’s objectives and the relationship between effort and performance, performance and reward, and reward and the individual’s objectives fulfillment. Individuals are encouraged, enlivened and satisfied to progress towards an outcome (goal) if they consider that their attempts will yield constructive and fruitful outcomes (phenomenal performance), which is followed by an outcome or reward that is valued (valence) [

34].

1.1.4. Adam’s Equity Theory

Adams [

42] equity theory clarifies that individuals tend to compare between the input and the output of a job, which implies that they compare workload they undertook and the number of hours they work with the pay benefits, reward and others they received. When the ratio of the input and the output are not equal, individuals tend to be disappointed, creating job dissatisfaction. Individuals tend to compare among fellow friends whom they feel are of the same class while on the other hand, they experience job satisfaction when the ratio between the input and the output is equal and it gives an avenue for inspiration for the employee or the person to raise the level of contribution for better output or keep up the consistency of the employment. Researchers assume understandings from the Adam’s equity theory that the main idea is the balance between the service they render and the advantages they get. It is predominantly concerned with comparing workload and the benefits of the employees. Employees consider their salaries reasonable if the salaries are viewed as equal to those of other employees in other organizations. If the employees are perceived as similar to their own, then the motivated performance will also drop to the same value and so on. The theories predict that job satisfaction from both personality and situation factors depend on fairness of benefits [

34].

6. Discussion

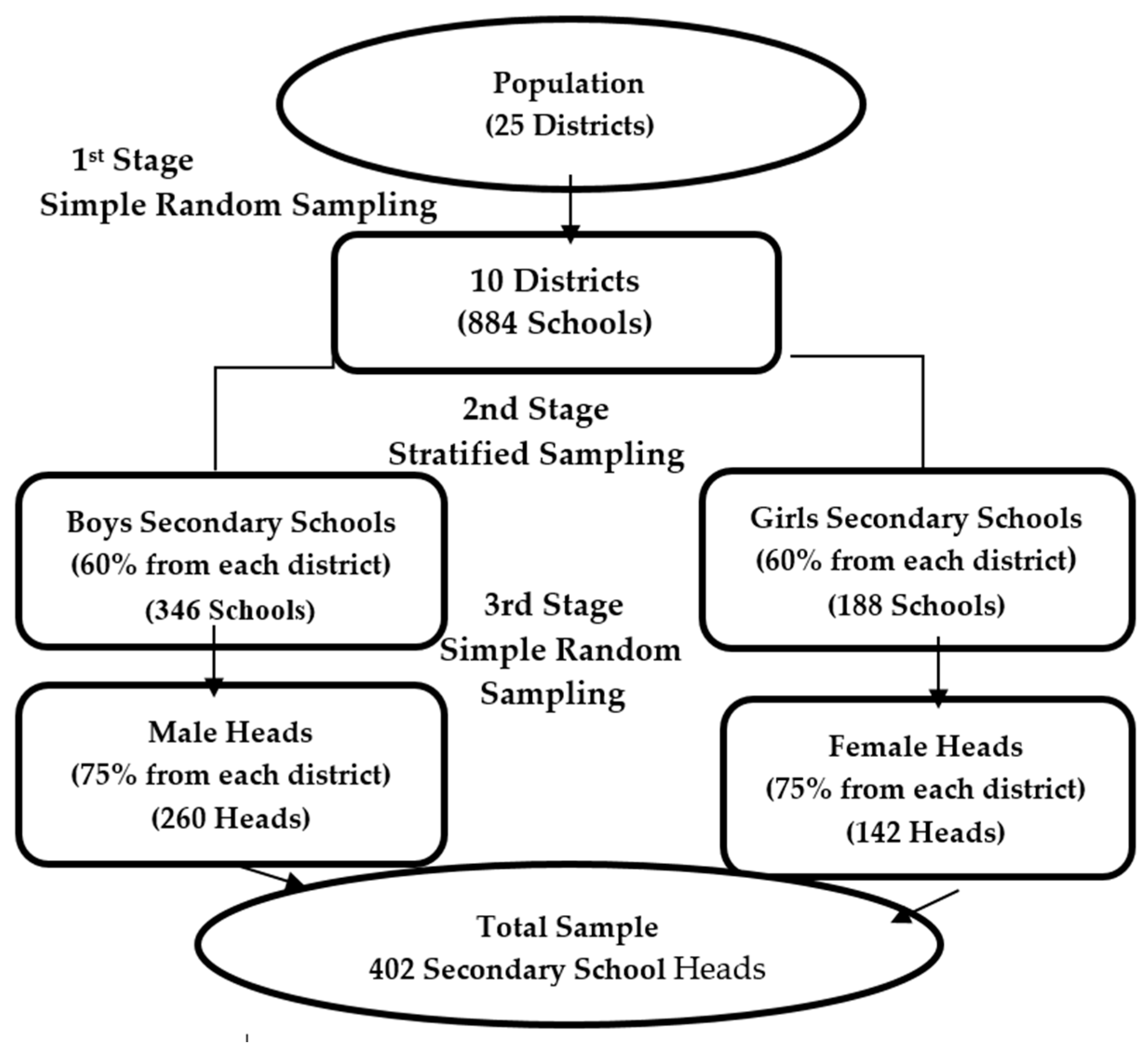

The purpose of the study was to examine and compare the job satisfaction of male and female secondary-school heads with respect to extrinsic and intrinsic factors in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It was a descriptive and quantitative study and therefore, descriptive survey research design was used. To collect information from the participants, a standardized tool i.e., the “Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire” (MSQ) was used. Raw data was collected, organized, classified, tabulated, and analyzed through proper descriptive statistics (i.e., mean, standard deviation) and inferential statistics (i.e., independent samples t-test). The result revealed that overall secondary-school heads were found satisfied intrinsically and dissatisfied extrinsically. They were satisfied with twelve intrinsic and extrinsic subscales i.e., achievement, activity, authority, co-workers, independence, moral values, recognition, responsibility, security, social service, social status, variety while they were dissatisfied with eight intrinsic and extrinsic subscales i.e., ability utilization, advancement, education policies and practices, compensation, creativity, supervision (HR), supervision (technical), and working conditions.

Based on gender analysis, male secondary-school heads were found satisfied intrinsically and dissatisfied extrinsically with their job. They were satisfied with twelve intrinsic and extrinsic subscales i.e., achievement, activity, authority, co-workers, independence, moral values, recognition, responsibility, security, social service, social status, variety, and they were dissatisfied with ability utilization, advancement, education policies and practices, compensation, creativity, supervision (HR), supervision (technical), and working conditions. On the other hand, female secondary-school heads were also found satisfied intrinsically and dissatisfied extrinsically with their job position on the whole. They were satisfied with twelve intrinsic and extrinsic subscales i.e., achievement, activity, authority, co-workers, independence, moral values, responsibility, creativity, security, social service, social status, and variety, and they were dissatisfied with ability utilization, advancement, education policies and practices, recognition, compensation, creativity, supervision (HR), supervision (technical), and working conditions. The results are consistent with the findings of Iqbal, Arif, and Abbas [

47] and Rajendran and Veerasekaran [

21] who acknowledged that the respondents showed slight satisfaction with the key eight sub-scales of their job i.e., ability utilization, education policies, advancement, compensation, independence, creativity, recognition and working condition. Ali et al. [

20] found that on the whole academic and administrative employees were satisfied with responsibility, authority, security, achievement, recognition, and variety while they exhibited low satisfaction with creativity, independence, and ability utilization. Also, they found that they were not satisfied with three facets of their job i.e., advancement, education policies and compensation. It obviously reveals that the outcomes of this research study support the findings of the current study in many facets however it contradicts in a few facets i.e., supervision (HR), supervision (specialized), advancement, compensation and working conditions. Likewise, the investigation of David and Wesson [

48] reported that advancement opportunities were not common in public sector organizations therefore discourage the competent and qualified workforces from remaining in the employment.

Ayele [

34] claimed that organizational policy and its management has a sound association with the organizational effectiveness and employees’ performance. The outcomes of the study revealed that secondary-school heads were not pleased with education policies which have antagonistic and adverse influences on school achievements. They responded that education policies and practices are not effectively implemented which contributes to negative consequences for school achievements. Furthermore, they added that the policies and practices toward employees of school system were disappointing. Also, they responded that employees of education were mistreated. The findings are in line with the findings of Mahmood [

19] who found that secondary-school teachers were less satisfied with education policies. Likewise, the findings support the results of Green [

49] who concluded that the chairpersons encountered minimal satisfaction with education policies. Ghazi [

18] investigated that government policies were not in the support of workers. Furthermore, he found that freezing of house rent, appointments of non-departmental officers, stoppage of advance increments and move-over in service, contract basis appointments policy, scrutiny committees, army surveys, political interference, new terminating rules, privatization of institutions, frequent change of curriculum and assessment system without proper guidelines were the key grounds for low satisfaction.

A few investigators believe that job satisfaction is emphatically concerned with the opportunities for advancement [

50]. The investigation of David and Wesson [

48] revealed that restricted advancement opportunities were common in public sector organizations, in this manner demoralizing the qualified employees from staying in the employment. Abdullah, Uli, and Parasuraman [

22] claimed that failure to acquire advancement or promotion is a hit to a person’s self-regard causing dissatisfaction and disappointment in work. The findings of the current study reveal that secondary-school heads were dissatisfied with advancement. They have no opportunities for the advancement on their job. Promotion policies are unsatisfactory. As per Grace and Khala [

51], compensation package is the most vital factor regarding job satisfaction. Wage, pay or salary is viewed as a noteworthy reward to inspire the employees and their behavior towards the achievement of employers’ goals [

24]. Hygiene factors such as compensation is a fundamental indicator of employment fulfillment. Therefore, pay will influence employees’ level of job satisfaction [

52,

53,

54]. The current study revealed that secondary-school heads were not pleased with their compensation and they were given insufficient salaries as compared to their job responsibilities. Their salary packages were not equivalent with those having the same job and scale in other departments. The findings also support the results of Ali [

55] who found that the entire academic and administrative staff were displeased with their compensation.

Performance and proficiency of the workforce may be improved by considering them and their necessities. The outcomes of the present investigation uncovered that secondary-school heads were disappointed with supervision (human relations) and supervisions (technical). They responded that District Education Officers (DEOs) lack technical knowledge and were incompetent in making effective decisions. Their ways of delegation of work to others and their ways of training their employees were unsatisfactory. Furthermore, they responded that DEOs handle their employees ineffectively. They were not serious in redressing the issues of their employees. The outcomes of the study support the findings of Toker [

56] who concluded that respondents exhibited the lowest level of satisfaction with supervision-technical, and supervision-human relations. Meanwhile the findings negate the findings of Mahmood [

19] and Ghazi [

18] who found that most of the respondents showed satisfaction with supervision (human relations) and supervision (technical). Conversely, Ghazi et al. [

57] concluded that instructors were neutral in responding with respect to supervision (technical).

In any organization, better working conditions are the most essential aspect of employment which positively affect employees’ job satisfaction. According to Robbins [

58], working condition has practical and positive effects on an employees’ job satisfaction on the grounds that employees desire physical surroundings that are safe, disinfected, conducive and friendly for work. The outcomes of the present study show that secondary-school heads were not pleased with the working conditions. They responded that there was lack of basic facilities such as poor power supply, lack of furniture, lack of water facility, no boundary walls, poor arrangement of sanitation, under-staffing, lack of advance library etc. which play an obstructive role in achieving institutional goals. The findings also support the findings of Mahmood [

19] who found that respondents were not pleased with the working conditions. Correspondingly, Ali [

55] concluded that the entire administrative and academic workforce were disappointed with the working condition.

Based on comparative analysis, there was no significant difference between the overall job satisfaction of male and female secondary-school heads. Both male and female secondary-school heads showed similar satisfaction/dissatisfaction with respect to overall intrinsic as well as extrinsic factors. However, male secondary-school heads were more dissatisfied with education policies and practices and creativity and more satisfied with moral values and responsibility than female secondary-school heads. The results are consistent with the findings of Oshagbemi [

24] who found that gender has no substantial effect on job satisfaction. Likewise, Koyuncu, Burke, and Fiksenbaum [

16] reported that there was no significant contrast in job satisfaction between male and female instructors. Similarly, Ali and Akhter [

17] expressed that there was no huge distinction between the perspectives of male and female employees with respect to job satisfaction. In the same way, Vorina, Simonič, and Vlasova [

59] concluded that there was no statistically significant difference in job satisfaction with respect to gender. On the contrary, the findings contradict with Ali et al. [

20] who found that there was a noteworthy contrast of job satisfaction between male and female secondary-school teachers. Research shows that females were reported to have high level of job satisfaction than males. Hauret and Williams [

23] claimed that females continue to show higher levels of job satisfaction than males in some countries, and the difference exists even after controlling many personal and job characteristics as well as working conditions. Ghazi [

18] found that female head teachers scored more than the males. In the same way, Mahmood [

19] also concluded that female respondents were more pleased and contented with their employment when contrasted with male respondents. Correspondingly, Mocheche, Bosire, and Raburu, [

60] concluded that female teachers showed slightly higher scores in job satisfaction than male teachers. On the other hand, Brogan [

25] announced that there was a substantial contrast between the job satisfaction of male and female principals; male principals were more satisfied than females.

7. Conclusions

Job satisfaction of employees in any organization is the leading variable for accomplishing organizational goals. An occupationally satisfied leader can develop the organization by ensuring vibrant environment, providing sufficient resources, ensuring good relations and an effective teaching-learning process. The findings reveal that both male and female secondary-school heads were satisfied intrinsically and dissatisfied extrinsically. In case of subscales analysis, male secondary-school heads were found satisfied with twelve intrinsic and extrinsic subscales i.e., achievement, activity, authority, co-workers, independence, moral values, recognition, responsibility, security, social service, social status, and variety, and they were dissatisfied with ability utilization, advancement, education policies and practices, compensation, creativity, supervision (HR), supervision (technical), and working conditions. On the other hand, female secondary-school heads were also satisfied with twelve intrinsic and extrinsic subscales i.e., achievement, activity, authority, co-workers, independence, moral values, responsibility, creativity, security, social service, social status, and variety, and they were dissatisfied with ability utilization, advancement, education policies and practices, recognition, compensation, creativity, supervision (HR), supervision (technical), and working conditions. Comparatively, overall, there was no significant difference between the job satisfaction of male and female secondary-school heads with respect to overall intrinsic as well as extrinsic factors. However, male secondary-school heads were more dissatisfied with education policies and practices and creativity and more satisfied with moral values and responsibility than female secondary-school heads.