Abstract

Computer-supported collaborative learning facilitates the extension of second language acquisition into social practice. Studies on its achievement effects speak directly to the pedagogical notion of treating communicative practice in synchronous computer-mediated communication (SCMC): real-time communication that takes place between human beings via the instrumentality of computers in forms of text, audio and video communication, such as live chat and chatrooms as socially-oriented meaning construction. This review begins by considering the adoption of social interactionist views to identify key paradigms and supportive principles of computer-supported collaborative learning. A special focus on two components of communicative competence is then presented to explore interactional variables in synchronous computer-mediated communication along with a review of research. There follows a discussion on a synthesis of interactional variables in negotiated interaction and co-construction of knowledge from psycholinguistic and social cohesion perspectives. This review reveals both possibilities and disparities of language socialization in promoting intersubjective learning and diversifying the salient use of interactively creative language in computer-supported collaborative learning environments in service of communicative competence.

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

Previous meta-analyses have reported that computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL), where individuals are encouraged or required in negotiation and sharing of meanings to solve problems at hand in groups or within organizations with the help of modern information and communication technology [1,2], markedly enhanced learning opportunities for non-native speakers [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. These overall advantages of CSCL were variously explained from different theoretical perspectives: computer-supported collaboration functions on the basis of “groupware” providing individuals with a higher level of information sharing, coordinating and navigating; social connectivity was enhanced through equal participation that was facilitated in the CSCL environment; and especially the socially distributed process of inquiry in CSCL has been underscored for building collective intelligence in such a technologically sophisticated collaborative language-learning environment. Nonetheless, limited systematic reviews of studies on synchronous computer-mediated communication (SCMC) have, to the author’s best knowledge, been conducted to synthesize the evidence for both linguistic competence and discourse competence on the basis of integration of cognitive elaboration with the social cohesion perspective, and to discern different pedagogical ideas on applicability of SCMC in various learning support infrastructures. Given the alleged interactive feature and social presence, there is no guarantee in the literature for the recognition and acknowledgement of language-related episodes of SCMC in normal classroom discourse and for the consistency between task-as-workplan and task-as-process that results in successful learner outcomes. Therefore, in view of Litterwood’s [11] category of communicative competence, this review coins linguistic and discourse competence as “organizational competence” (p. 243), then underscores the most pertinent variables as learner proficiency, modality, interactional pattern and learning context to examine groupware and intersubjective learning, and mainly investigates the quality of language output and learning experience through this groupware technology.

1.2. Objective

To discern both advantages and disadvantages of realizing CSCL technologies in enhancing personal learning environments (PLEs), this review concentrates on linguistic and discoursal features and online intersubjective learning experiences as generated from negotiated interaction and co-construction of knowledge. At the same time, this review lays emphasis upon affordances of synchronous communication in service of communicative practice and learner outcomes by examining interactional feedback and co-construction of knowledge. In addition, it is expected to demonstrate how an effective blend of interstitial space between instructional context and technology-enhanced collaborative learning possibly extends traditional notions of learning, interactional patterns so as to enhance communicative competence in a diverse CSCL environment.

2. Methods

In this review, computerized databases: ProQuest, ERIC, Google Scholar were used to search for full-text articles from 1990s–2017. In addition, four main online journals and organizational websites were reviewed for online research articles: Language Learning & Technology, CALICO, Computer Assisted Language Learning, TESOL Quarterly. Studies were inductively coded to generate key themes. In the first coding cycle, the investigator read all the studies for key codes that represent research foci. To facilitate cross-analysis and decoding, the second cycle of thematic procedure was to generate 5 conceptual parameters: lexical features, grammatical development, discourse strategies, communities of practice (CoPs) and identity expression based on the initial codes. With the investigator’s exclusive focus on language users’ grammatical knowledge of lexical, syntax and the like, as well as socio-interactional knowledge of communication strategies (CSs), conveying utterances appropriately and coherent construction of collective intelligence, these parameters were at last aggregated into 3 paradigms: (1) linguistic competence; (2) discourse competence; and (3) quality of technology-enhanced collaborative learning experience.

2.1. Research Questions

This present review herein adopts a social interactionist view to address the following research questions:

- What evidence is there for the impact of computer-supported collaborative learning on linguistic and discourse competence in synchronous communication?

- To what extent do synchronicity and intersubjectivity enhance comprehensible and authentic interactional modified output?

- To what extent do interactional patterns and sociolinguistic factors inform social presence and collective intelligence in cross-modality personal learning environments?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The social interactionist view is adopted to identify three key paradigms for synthesis: linguistic competence, discourse competence, and technology-enhanced collaborative learning experience. Selected studies examining these paradigms were reviewed with a special consideration to the role of groupware applications in creating favorable conditions for construction and maintenance of shared conceptions, establishment of interest communities and online personas. In this search, selection was limited to Integrative CALL period, i.e., the most up-to-date web 2.0 computer and information technology contributing to blended language learning and teaching as an agency, taking a sociocognitive point of view developed in social interaction [12,13], and synchronous computer-mediated communication. The majority of identified studies were set in ESL/EFL or FL higher education contexts from an intact classroom to a personal digital environment. When determining the eligibility of retrieved articles, studies with the following primary foci were excluded: use of synchronous communication for non-language learners; text-based CMC exclusively on writing skills.

2.3. Selection of Publication

The first stage was carried out in databases using a combination of key words. In the initial search, summaries, conference abstracts and commentaries were excluded; and at second stage the investigator focused exclusively on the integrative CALL in order to maintain a social interactionist approach. The majority of studies included in this phase looked into communicative practices and authentic discourse from sociocognitive perspective and took CSCL principally as Agency. To minimize publication and language bias, cited references and cross-disciplinary book chapters were also rated for inclusion criteria, but duplicated research deigns were excluded. Additionally, results drawn from comparative studies on synchronous and asynchronous CMC were found relevant in this review. To narrow down on the retrieved papers, inclusion of exact phrases (CoPs, online L2 identities, social presence, oral proficiency, Internet interest community) were paired with initial reference lists. It should be clarified that in this review organizational competence and quality of online learning experience were the main investigation. Based on the investigator’s prior knowledge, previous studies seemed to agree upon the facilitative role of text-based chat in learners’ writing skills and also argued for its possible transfer of skills to oral competence [14,15,16]. To examine the effect of written CMC on grammaticality and turn adjacency and provide plausible explanations, comparative studies looking into written CMC and results concerned with moderating variables such as interactional pattern (e.g., dyad, groupware), treatment length, socio-cultural and individual factors, etc. were also included for analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

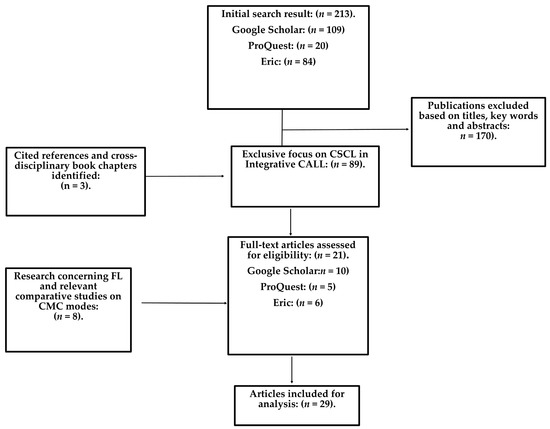

This flowchart (Figure 1) indicates educational databases search method and criteria identifying a total of 29 studies (2 non-empirical and 27 empirical studies).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the search process.

3.2. Social Interactionist Approach to Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning

In the background of Integrative CALL, transformative mode of delivery and conception of learning are called upon concomitantly with the inclusion and popularization of e-learning and technology-enhanced “groupware” in education. The field is growing with its promising efficacy in second language learning and teaching. In light of Swain’s [17] Output Hypothesis and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) [18], social interactionist approach incorporates socio-cognitive variables into constructivist and interactionist theories, and investigates the “reluctant” modified output and “more knowledgeable other” [19] facilitated by networked social interactions from both psycholinguistic perspective and social cohesion perspective. It offers an updated construct to look into key constructs as linguistic accuracy and complexity, discourse strategies, CoPs, CSCL, and quality of collaborative learning experience via synchronous communication.

To answer the first research question, this systematic review develops a social interactionist view to identify the principles of CSCL for communicative competence, and appraises consistency between these principles and the affordances of both synchronous oral CMC and written CMC. In investigating CSCL technologies, challenges such as disparity of distributed benefits of groupware applications, sociocultural and motivational factors deserve attention when we consider pedagogical implications of task-based SCMC. This is argued upon but not limited to mixed proficiency levels and linguistic and socioeconomic backgrounds in interactional composition; transferability resulting from relevancy between the delayed nature of asynchronous communication and the hybridity of text-based chat; and cognitive processing across learning tasks and contexts. It is evident that the above conditions concern the multimodality of SCMC (oral/aural vs. written). Hence, to answer the second and third research questions, it is beneficial to argue for cross-modality transfer of skills; patterns catered for certain group dynamics; opportunities for individual engagement in task-based SCMC. Such issues remain an immature area to be exploited for different pedagogical purposes.

4. Principles of CSCL for Communicative Purpose

Table 1 indicates that comparative studies (CSCL and traditional classroom; SCMC and asynchronous computer-mediated communication (ACMC), which enables users to conduct digital communication regardless of time and place [20]) have explored opportunities for L2 oral proficiency development in the CSCL environment. Based on the first thematic coding procedure, key codes as lexical range, corrective repair, discourse and syntactic complexity, discourse and participation were exploited with the purpose of investigating lexical features, discourse strategies, online personas and identity expression in CSCL. The according supportive principles were well reported in line with psycholinguistic SLA-based and social interactionist SLA-based framework as on quantity of language, and joint meaning-making in the way it provides frequent opportunities for (1) authentic input and meaningful negotiated interactions aiming at a greater variety of linguistic and discoursal features; (2) modifications and reflection during metalinguistic process; (3) language socialization upon collective intelligence and anxiety easement in digital PLEs.

Table 1.

Studies examining principles in the CSCL environment.

4.1. Linguistic Competence

Lexical range and density, and syntactic complexity were served as independent variables to investigate quantity and quality of L2 output in different modes. Incidental negotiations in response to communication gaps caused by lexical and syntactical confusions stimulate learners to initiate reciprocal meaning-making in synchronous communication, which directs their attention to interlanguage grammaticality. Compared to F2F discussions, oral computer-mediated communications (OCMC, i.e., digital communication in form of audio-based, video-based chat) is designated as a more effective preparatory modality in respect of lexical range, pronunciation and communicative units [21,22,23]. As far as the morphosyntactic negotiations, results vary from comparative studies to those who were exclusively on AudCMC. For instance, lexical triggers were greatly responsible for these incidental negotiations in contrast of paucity of syntactic repair [24], and only ACMC statistically stood out in provoking morphosyntactic triggers [25]. Additionally, no significant difference was found among the groups (written SCMC/ACMC, control group) in quality of language output in terms of lexical richness, diversity, and syntactic complexity [4]. This seems to go against the findings that 86.3% of phonetic triggers and 51.6% of lexical triggers in AudCMC caused negotiation and supported both negotiation of meaning and form [22]. Therefore, this review deems it essential to investigate written mode as equally to further compare and analyze online discourse across modalities with types of dyad setting. More comparative research is needed to properly address whether negotiation routines provoke interactional feedback and repair moves as such to contribute to noticing and learner uptake.

4.2. Discourse Competence

With regard to discourse competence, many previous experiments corroborated relative contributions of written mode to rich input and output in dynamic learner-centered discourse community [25,27,28,29]. Those research were usually designed with task-based activities such as decision-making tasks, jigsaw, and information gap to potentially elicit interactional feedback such as recasts, explicit correction, elicitation response. As SCMC is theoretically comparable to F2F interactions with higher level of collaboration among individuals in groupware, socially-oriented activities trigger more meaning construction movements along with lexically denser and syntactically complicated language. Noticeable findings can be found regarding quantity and types of discourse functions in SCMC. Whereas more negotiation turns and relatively fewer instances of actual negotiation routines were evidenced in OCMC, negative feedback in written computer-mediated communication (WCMC, i.e., written form of digital communication, generally referring to text-based chat) were found similar to F2F interactions and more versatile [23,25]. Such divergence can be explained by the nature of turn adjacency in WCMC where interactants simultaneously type messages which are shown based on sending order instead of writing, and thus feedback and response to action can be asymmetrical. A counter-evidence is that F2F and synchronous WCMC clearly differ in discourse sequence, in that as a hybrid medium, this modality might mirror the delayed nature of ACMC. If that is the case, additional time for codification and decodification leads to fewer non-communication triggers at the same time that it facilitates noticing features in negative feedback. However, few studies have exhibited such a direct link between ACMC and WCMC in one experiment. Unexploited results due to the complexities of turn adjacency, and negative feedback regarding the multimodality of SCMC indicate a productive line of focusing on asymmetry of morphosyntactic interactions in written mode and asynchronous communication.

5. Quality of L2 Output in Synchronous Communication

Table 2 investigates intentional transfer of skills from written to spoken mode in task-based SCMC.

Table 2.

Studies examining the interplay of learner proficiency and variance of interactional feedback and repair move in cross-modality synchronous communication.

In the background of psycholinguistic and social cohesion theories, this review pinpoints learner proficiency as an independent variable and educational level as a covariate in analyzing co-constructing learning in the process of language socialization. It should be well acknowledged that some researchers ran proficiency tests while some did not, so the former judgement was made based on the generally even number of proficiency levels spread out across modality analysis (4 advanced, 6 mixed, 5 intermediate, 4 elementary). The latter was coded based on original background information such as educational level and course they had completed. To eliminate possible bias, 3 studies also enrolled participants from online learning community with entirely anonymous identity. It is hypothesized that successful learner uptake leads to communicative competency [19,28,36,39]. Results regarding learner proficiency diverge in different modalities of SCMC. Evidence supports that higher-span non-native speakers are most likely to solve syntactic ambiguities and notice recasts from their interlocutors [30,33,35]. However, discussion about indirect transfer of skills from written to oral mode lends itself to beneficial effects for lower PWMC learners [25,28,34]. From psycholinguistic perspective, Levelt’s [40] model of language production and concepts in working memory capacity (WMC) are the rationale to predict affordances in synchronous WCMC for L2 oral proficiency development. Comparing two modalities, voice chat was more conducive to negotiation turns and elaborated responses than text chat [14,21,22,23]. However, written texts were also proved as an indispensable aid for participants in spoken tasks [14]. Payne and Whitney [15] pointed out that simultaneous text-based exchanges produced the similar underlying cognitive mechanism for L2 speech. That is, through meaningful social interactions, both socially and physically distributed cognition are combined between and among several agents to make limited and inconsistent explanations from low-span agent available to move forward with the activity. As to individual differences in WMC may affect the frequency of repetition and other patterns of language use in chatroom discourse, more frequent repetition and relexicalization were found from lower PWMC learners in the attempt to maintain the conversational flow via recycling of linguistic forms from prior talks into current ones. Positive evidence of cross-modality transfer of skills is consolidated by affordances in synchronous WCMC, such as (1) versatile turn-taking patterns and non-ephemeral cues in chatroom sessions [41]; (2) “participatory” social presence accountable for communicative continuum [39,42]; (3) more communication strategies aiming at meaning-based tasks coupled with additional information about the non-understanding/misunderstanding items and concepts due to the paucity of paralinguistic cues [15,16,28,33,43].

6. Quality of Technology-Enhanced Collaborative Learning Experience

Table 3 lists studies examining types of negotiation triggers, quantity and quality of negotiation routines, grammaticality of learner output, power relationship in CoPs, types of error corrections, and response to negative feedback episodes. The examined interactional patterns cover the range from mixed-levels of proficiency dyad to groupware; from disclosed most likely partners to anonymous identity status.

Table 3.

Examine interactional feedback in learner patterns in synchronous communication.

Positive impacts of computer-supported collaborative “focus on form” on grammatical accuracy is partially warranted in NNS-NNS and NNS-NS pattern [5,25,28,36,39]. The ECEs generated in NNS-NS interactions were deemed to facilitate authentic language input and interactional modifications regarding morphosyntax, lexicons and pronunciation with a wealth of target-like linguistic and stylistic features [14,21,22,25,31,32]. This finding is also confirmed by Jepson [32] that NNS-NS is the most beneficial pattern in pronunciation. It is significant that amounts of phonetic LREs produced modified output followed by morphosyntactic LREs and lexical LREs [22]. In a way, there seems to be a greater possibility of successful learner uptake in NNS-NNS than in NNS-NS pattern. Furthermore, NNSs-NNSs with different L1 have been observed with higher amount of phonetic and lexical LREs. Possibly due to the same L1, dyads shared similar contextual and background information and easily reached complete understanding while L1 interference and transfer may result in extra LREs in NNSs-NNSs Diff L1 group. With regard to types of triggers and indicators, deviations exist in studies where researchers focused on AudCMC and where they compared oral and written mode. It seems in those comparative studies across modality, there is usually a clear abundance of global LREs (41% in AudCMC, 39% in VidCMC) [23,31]. Whereas, local triggers for OCMC were rather prominent in exclusive examination of SVCMC [21,22,31,45,46]. To give a closer investigation of designs of these research, such divergence could possibly be interpreted by the profile of their participants. For example, in Fernández’s [31] research, sample size of NNSs-NNSs dyads were limited, while NNSs-NNSs Diff L1 group from Bueno’s [21,22] research were all preservice teachers who might have known all forms of interactional feedback. In this case, it is rather partial to apply to all EFL learners. Since Yanguas [23] only concerned Spanish L1 learners, not too many comparable results can be drawn, but it does share some common ground with NNSs-NNSs Same L1 [21,22]. Therefore, more parallel research need to properly address this issue.

Another interesting finding in NNS-NNS interaction is that morphosyntactic feedback was most often provided by recasts [44], whereas only explicit correction was recorded as the most used technique for NF [21,22,23]. Previous research has shown that among attempts to balance and maintain flow of interactive discourse in synchronous communication, remix of language is a prominent predictor in co-construction of knowledge for low-span speakers [13,47,48]. The main concern here is that the actual “language recycling” may bootstrap lower-proficient NNSs partners into non-target linguistic forms when they fail to balance function-to-form and meaning-to-form behaviors. On the other hand, availability of time in textual interactions could also pose anxiety and disproportionate participation to lower proficiency-level speakers if required presence, forced output and individual accountability are specifically reinforced in collaborative learning with technology [34,35].

Table 4 indicates that learning contexts can, by design, reduce burdens on language production and consumption mechanisms for disadvantaged learners. From a social cohesion perspective, studies covered sociocultural and motivational factors of synchronous communication in building CoPs and user-friendly PLEs.

Table 4.

Studies examining co-construction of knowledge in different learning contexts.

The purposes of investigating synchronous communication in PLEs were reported variously as: an establishment of parameters for effective communicative language learning; an aid/supplement for face-to-face (F2F) discussions; bridging gap between theoretical CSCL framework and classroom-based discourse; or improving linguistic accuracy and fluency; as well as the advancement of task-based teaching and learning with technology.

As reviewed, the majority of studies are located in blended learning contexts where social dynamics in groupware are well established and consistent. It is also necessary to examine core concepts such as “co-constructing learning”, “interest community”, “identity expression”, “communities of practice”, “significant others” in personal digital learning environments where participants rarely or never meet face-to-face. For instance, perceived positive educational impacts on learners were seen in SNSs as improved attitudes, greater motivation and lower level of boredom towards online course; optimal anxiety level for online experience as negotiating and sharing ideas in non-threatening online communities; impression and interpersonal relationship management and maintenance [10,19,32,50,51]. It is desirable that in learner-centered PLEs, phenomenon of identity expression in CoPs develops their online personas in confrontation of a broad sense of audience and sense of social presence in the way non-native speakers actively shift their role from “novice learners” to “significant mediators” via manipulating L1, modifying L2, taking ownership and personalizing learner needs.

7. Discussion

Overall favorable conditions were perceived in both written and oral synchronous computer-mediated communication as a “cognitive amplifier” [26] (p. 472) and a “conversational simulator” [20] (p. 198). Different learning opportunities are provided by OCMC as in fluency and pronunciation and by WCMC in accuracy and syntax [37]. OCMC imposes inter-personal pressures on interlocutors and the turn taking patterns resemble F2F interaction with greater emphasis on task completion via more repair moves targeting comprehensible pronunciation. In this case, OCMC has been hailed to produce more CSs, fewer disrupted discourse and co-construction of target language in audio-/video-based interactions. In addition, studies also looked into transferability of text chats to oral skills by specifying language units and organizational skills while measuring features of oral proficiency. Reviewed evidence on learner proficiency and modality lends further credence to the notion that synchronous WCMC work as “simulator” and pre-production phase for speaking practice to happen at paragraph level, and low-span learners’ noticing of their own problematic linguistic output and of reciprocal teacher-like feedback from their interlocutors. However, it is also noticeable that in measuring the underlying cognitive mechanism, there was a crossover in score levels in non-word repetition tests and reading span tests employed in two studies [15,16]. Given that learning conditions include learning task, medium and may levy different cognitive demands on WMC, studies need to be replicated with a proper design of test measures and instructional treatments.

In spite of the above deviations, this review also argues for some internal consistency among studies. Firstly, as to quantity and types of negotiation triggers and indicators, NNSs with the same L1 naturally assumed their partners would not know the items, and thus they omitted the indicator and anticipated synonyms as a response. In addition, the lexical search technique of resorting to native language in solving communicative problems explains fewer instances of actual negotiation routines [14,21,22,32,45,46]. Therefore, apart from learner proficiency, familiarity of or shared socio-cultural and linguistic background facilitates comprehension and interpretation, thus decreasing the need for negotiation.

Secondly, with regard to grammatical development, contrary to previous research which had stated that AudCMC dyads only managed to reach 45% of complete understanding of target lexicons being negotiated and did not produce adequate morphosyntactic negotiations [15,16,26,33,43], SCMC has the potential for focus on both form and meaning, and especially phonetically modified output were most significant [14,21,22,31]. This suggests that grammatical triggers do provoke notice and possible negotiation. However, whether such negotiation routines would lead to final learner uptake is under great debate. Such deviation still raises questions of whether the inclusion of phonetics in focus on meaning episodes would yield a higher percentage of focus on form in meaning-making tasks.

Thirdly, the reliability and generalizability of these findings are subjected to the limited sample size and treatment length. Especially in a personal digital learning environment, learning support infrastructure, online registrants’ readiness to social bonding, random partnership, equality of engagement are all constraining factors and it takes time for co-construction of knowledge to lead to language socialization and oral proficiency [52,53]. The present results in SCMC research regarding communicative practices also concern group dynamics. Comparatively, groups with competitive dynamics will exhibit higher telepresence than groups with egalitarian dynamics [40,54]. In addition, those with greater autonomous motivation are also more likely to take control in interactional turns. An interesting finding as a result of a specific learner’s linguistic background and learning style is the versatility of triggers and frequent use of explicit correction as negative feedback. For instance, Spanish learners prefer explicit corrective feedback [48]. Coded opportunities of ECEs recorded no learner-initiated error correction in NNS-NS dyad when “polite” culture from American NSs’ is involved [25,28]. Such results confirm the phenomenon that NSs partners/tutors tend to ignore syntactic errors or give implicit salient cues or delayed corrective feedback. It is worth mentioning that the personal learning environment involves greater variety of learner backgrounds, and participants’ actions are normally bound by sociocultural conventions and personalities. The similar case is with NSs and more advanced NNSs in balancing and maintaining communicative discourse, as negative feedback in NNS-NNS outnumbered NNS-NS patterns, except for reactive indirect feedback [24,28,48,55]. As a result, disparity of who engages and who actually benefits makes democratization principle a debatable issue in collective intelligence. This fact warrants longitudinal studies on quality of collaborative learning experience to gain deeper insights into interactional patterns in different settings, learner opportunity to interactional feedback and effects exerted by different kinds of dyads on successful learner uptake.

8. Conclusions

Closely informed by the social interactionist view, this review presents possible capacities provided by the computer-supported collaborative learning environment for communicative practice. A follow-up examination of 4 interdependent variables reveals how these principles are applied into synchronous communication to improve language users’ oral skills, social presence and collective intelligence. To comprehensibly evaluate individual online learning experiences, sociocultural factors (e.g., social dynamics), individual characteristics (proficiency level, personality, tolerance scale, etc.), asymmetry of dyad setting and groupware, and treatment length all need to be included into future research. This review also sheds light on the possible expansion of instructional CSCL activities in digital environments where autonomous and independent learning mostly takes place. Guidance and support should be tailored to mediate differential technology-enhanced pedagogy in learner-initiated personal learning environments with a shift of education practitioners’ role from “sage on stage” to “guide on side”. Apparently, digital literacy training for classroom practitioners is also expected to maximize advantages of learning conditions for communicative practice in blended learning environments and also to better prepare learners on the trajectory towards their personal integration of collaborative learning with technology.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my former supervisor Mairin Laura Hennebry and all three reviewers for a wealth of insightful comments and suggestions, all of which—in one way or another—have been reflected in the current version of the paper. This paper is also debited to support from my family and friends.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACMC | asynchronous computer-mediated communication |

| AudCMC | audio computer-mediated communication |

| CoPs | communities of practice |

| CSCL | computer-supported collaborative learning |

| ECEs | error corrective episodes |

| F2F | face-to-face |

| IFL | Italian as a foreign language |

| IPC | Increased Participation in Computer Mode |

| LREs | language-related episodes |

| OCMC | oral computer-mediated communication |

| PLEs | personal learning environments |

| PWMC | phonological working memory capacity |

| SCMC | synchronous computer-mediated communication |

| SNS | social networking site |

| VidCMC | video computer-mediated communication |

| WCMC | written computer-mediated communication |

| WMC | working memory capacity |

| ZPD | Zone of Proximal Development |

References

- Belz, J. Social dimensions of telecollaborative language study. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2002, 6, 60–81. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, T. What is Web 2.0: Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. Commun. Strateg. 2007, 65, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, L. Computer-mediated glosses in second language reading comprehension and vocabulary learning: A meta-analysis. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2008, 21, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, Z.I. The effects of synchronous and asynchronous CMC on oral performance in German. Mod. Lang. J. 2003, 87, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuSeileek, A.F. The effect of computer assisted cooperative learning methods and group size on EFL learners’ achievement in communicative skills. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuSeileek, A.F.; Qatawneh, K. Effects of synchronous and asynchronous computer-mediated communication (CMC) oral conversations on English language learners’ discourse functions. Comput. Educ. 2013, 62, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, D. Using computer networking to facilitate the acquisition of interactive competence. System 1994, 22, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, D.M. Computer-mediated discourse in instructed environments. In Mediating Discourse Online; Magnan, S., Ed.; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, D.M.; Payne, J.S. What makes students click: Working memory and look-up behavior. System 2004, 32, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, S. Computer-Mediated Communication: Linguistic, Social and Cross-Cultural Perspectives; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood, W. Communicative and task-based language teaching in East Asian classrooms. Lang. Teach. 2007, 40, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, S. CALL: Past, present and future. System 2003, 31, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Poel, K.; Swanepoel, P. Theoretical and methodological pluralism in designing effective lexical support for CALL. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2003, 16, 173–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.-J. Can synchronous computer-mediated communication (CMC) help beginning-level foreign language learners speak? Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2012, 25, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.S.; Whitney, P.J. Developing L2 oral proficiency through synchronous CMC Output, working memory, and interlanguage development. CALICO J. 2002, 20, 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, J.S.; Ross, B.M. Synchronous CMC, working memory, and L2 oral proficiency development. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2005, 9, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, M. The output hypothesis and beyond: Mediating acquisition through collaborative dialogue. In Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning; Lantolf, J.P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S.L.; Black, R.W.; Sykes, J.M. Second Language Use, Socialization, and Learning in Internet Interest Communities and Online Gaming. Mod. Lang. J. 2009, 93, 802–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauvois, M.H. Conversations in slow motion: Computer-mediated communication in the foreign language classroom. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 1998, 54, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Alastuey, M.C. Synchronous voice computer-mediated communication: Effects on pronunciation. CALICO J. 2010, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Alastuey, M.C. Interactional feedback in Synchronous Voice-based Computer-Mediated Communication: Effect of Dyad. System 2013, 41, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanguas, I. Oral computer-mediated interaction between L2 learners: It is about time. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2010, 14, 72–93. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, R.J. Computer mediated communication: A window on L2 Spanish interlanguage. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2000, 4, 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sotillo, M.S. Discourse functions and syntactic complexity in synchronous and asynchronous communication. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2000, 4, 82–119. [Google Scholar]

- Warschauer, M. Comparing face-to-face and electronic discussion in the second language classroom. CALICO J. 1996, 13, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, G.; Koschmann, T.; Suthers, D. Computer-supported collaborative language learning: An historical perspective. In Cambridge Handbook of Learning Sciences; Sawyer, R.K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 409–426. [Google Scholar]

- Sotillo, M.S. Corrective feedback via instant messenger learning activities in NS–NNS and NNS–NNS dyads. CALICO J. 2005, 22, 467–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaffar, J. Networking Language Learning: Introduction. In Language Learning Online: Theory and Practice in the ESL and L2 Computer Classroom; Swaffar, J., Romano, S., Markley, P., Arens, K., Eds.; Labyrinth Publications: Austin, TX, USA, 1998; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fitze, M. Discourse and participation in ESL face-to-face and writing electronic conferences. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2006, 10, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Garciá, M.; Martínez-Arbelaiz, A. Learner’s interactions: A comparison of oral and computer-assisted written conversations. ReCALL 2003, 15, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, K. Conversations—And negotiated interaction—In text and voice chat rooms. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2005, 9, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Salaberry, M.R. L2 morphosyntactic development in text-based computer communication. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2000, 13, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satar, H.M.; Özdener, N. The effects of synchronous CMC on speaking proficiency and anxiety: Text versus voice chat. Mod. Lang. J. 2008, 92, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S. Exchanges ideas with peers in network-based classroom: An aid or a pain? Lang. Learn. Technol. 2001, 5, 103–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, C.; Zhao, Y. Noticing and text-based chat. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2006, 10, 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, Y.-W.; Higgins, S. Learners’ use of communication strategies in text-based and video-based synchronous computer-mediated communication environments: Opportunities for language learning. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2016, 29, 901–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cziko, G.A.; Park, S. Internet audio communication for second language learning: A comparative review of six programs. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2003, 7, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L. Learners’ perspectives on networked collaborative interaction with native speakers of Spanish in the U.S. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2004, 8, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Levelt, W.J.M. The ability to speak: From intentions to spoken words. Eur. Rev. 1995, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Epigenesis of Identity: Identity, Youth, and Crisis; Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L. A study of native and nonnative speakers’ feedback and responses in Spanish-American networked collaborative interaction. In Internet-Mediated Intercultural Foreign Language Education; Belz, J., Thorne, S., Eds.; Heinle & Heinle: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 147–176. [Google Scholar]

- Roschelle, J.; Behrend, S. The construction of shared knowledge in collaborative problem solving. In Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning; O’Malley, C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1995; pp. 69–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, A.; Gass, S.; McDonough, K. How do learners perceive interactional feedback? Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2000, 22, 471–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. Computer-mediated negotiated interaction: An expanded model. Mod. Lang. J. 2003, 87, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. The use of communication strategies in computer-mediated communication. System 2003, 31, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deusen-Scholl, N.; Frei, C.; Dixon, E. Coconstructing learning: The dynamic nature of foreign language pedagogy in a CMC environment. CALICO J. 2005, 22, 657–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinagre, M.; Muñoz, B. Computer-mediated corrective feedback and language accuracy in telecollaborative exchanges. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2011, 15, 72–103. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R.; Thomas, M. Identity in Online Communities: Social Networking Sites and Language Learning. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Soc. 2009, 7, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, K.P.; Holcomb, L.B.; Smith, B.V. The use of alternative social networking sites in higher educational settings: A case study of the E-Learning benefits of Ning in education. J. Interact. Online Learn. 2010, 9, 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, M. Variations in motivation, anxiety and boredom in learning English in Second Life. EUROCALL Rev. 2015, 23, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanovic, O. Learning and teaching in a synchronous collaborative environment. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 1999, 15, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L. Processes and outcomes in networked classroom interactions: Defining the research agenda for L2 computer-assisted classroom discussion. Lang. Learn. Technol. 1997, 1, 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, M.; Stockwell, G. CALL Dimensions: Options and Issues in Computer-Assisted Language Learning; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tudini, V. Using native speaker in chat. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2003, 7, 141–159. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).