Abstract

This paper investigates the potential of conceptual divergences within and between languages for providing intellectual resources for theorizing. Specifically, it explores the role of multilingual researchers in using the possibilities of the plurality of intellectual cultures and languages they have access to for theorizing International Service Learning (ISL). In doing so, this investigation of conceptual divergence within/between languages shows how it is possible for multilingual researchers to extend their capabilities for theorizing; to bring forward possibilities for theorizing ISL in languages other than English; and to potentially bring new perspectives to a field of enquiry which lays claim to being “international”. The process of developing the capability for theorizing begins by exploring the divergence in languages of key concepts. In this instance, the analysis focuses on the English concept of “service learning” which is rendered in Tiếng Việt (i.e., Vietnamese language) as học tập phục vụ cộng đồng. The analysis of the conceptual divergence represented by these Tiếng Việt concepts opens up insights into ways of developing the capabilities that multilingual researchers have for theorizing. In effect, this paper contributes to the knowledge about the options multilingual researchers have for using their full linguistic repertoire for the purpose of theorizing. The study has significant implications for multilingual education, multilingual research and theorizing ISL in universities which privilege English-only monolingualism.

1. Introduction

The paper adds to cutting-edge research which is exploring the possibility that multilingual Higher Degree Researchers (HDRs) might develop their capabilities for theorizing through using their full linguistic repertoire. Specifically, this paper is based on Singh’s [1] ground-breaking and thought provoking post-monolingual research methodology. Based on Singh’s generative and highly productive research and intellectual leadership in post-monolingual education and research, this paper provides an account of the use English and Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese language) in research into International Service Learning (ISL). Specifically, Tiếng Việt concepts and an associated image are explored for their potential value for developing the capabilities for theorizing ISL. Internationalizing education, of which ISL is a significant part, has produced demographic changes in universities which operate only in English through a substantial increase in the presence of multilingual HDRs. Given that this multilingual presence is a function of the internationalization of education, this paper brings to the fore questions about the uses of multilingual HDRs’ full linguistic repertoire and the knowledge it provides access to for theorizing ISL. In doing so, it contributes to efforts to position multilingual HDRs’ languages as educationally productive resources which can be used to develop their capabilities for theorizing, and broaden the English-only monolingual approach to internationalizing Anglo-American centered education [1].

This paper explores ways in which Tiếng Việt concepts might contribute to internationalizing the theorization of ISL. A range of studies illuminate how the internationalization of universities from countries such as the USA, the UK and Australia promulgate their structures of knowledge/language/power through epistemic activities associated with the privileging of the English language and Anglo-America [2]. This research raises questions about ways to open up the possibilities for “declining” from theorizing from English-only monolingualism by inviting multilingual HDRs to develop their capabilities for theorizing using their full linguistic repertoire. Ontologically, research-driven knowledge production and dissemination is necessarily conducted in a particular language. In other words, languages are integral to theory and theorizing. Multilingual HDRs are using theoretical tools from their languages for analytical purposes to declassify the division of intellectual labor which assigns theory to English, and data to other languages [3]. Here the concept of “Tiếng Việt theoretic-linguistic tools” refers to concepts and images in Tiếng Việt which can be used as analytical tools in research into ISL which is largely written in English. However, it must be emphasized that “Tiếng Việt theoretic-linguistic tools” does not refer to any uniqueness of these tools that are peculiar to Người Việt (Vietnamese people) or Tiếng Việt. The concept “Tiếng Việt theoretic-linguistic tools” is not used to claim any Người Việt ethno-national essence, but to the possibility of generating and using concepts in and from this language (and thus any other languages). Thus, the use of the term “Tiếng Việt theoretic-linguistic tools’ is similar to Jullien’s notion of “Chinese thought, [which designates] the thought which has been expressed in Chinese […] in the same way ‘Greek thought’ is that which is expressed in Greek” [4] (p. 147).

The focus of this paper is on developing multilingual HDRs’ capabilities for theorizing, in this instance, through using Tiếng Việt theoretic-linguistic tools to conceptualize ISL. Conversely, this paper is not trying to generate a precise meaning for ISL through the use of Tiếng Việt. The concept of ISL has been a focus for much contestation over the years [5]. In effect, ISL is a much contested concept. Contested concepts are “not resolvable by argument of any kind, [but] are nevertheless sustained by perfectly respectable arguments and evidence” [6] (p. 169). However, an appreciation of the value of the contested concepts used to theorize ISL is integral to post-monolingual research in this field. The purpose of this paper is to invite researchers, both Người Việt and Người nưới ngoài (Foreigners) who are proficient in Tiếng Việt to develop their capabilities for generating theoretic-linguistic tools in this language.

To do so, this paper begins by defining theorizing. Then it explores the question of whether current theorizing of ISL is reciprocal or partisan. As part of this literature review, Singh’s [7] concept of “reciprocity in post-monolingual theorizing” is introduced. The section that then follows provides a brief explanation and justification of the method used in the research reported in this paper. The results section addresses four key findings. The terms used by Vietnamese universities for subjects/courses relating to service learning offer a basis for exploring the conceptual divergences between English and Tiếng Việt as a way to open up possibilities for multilingual HDRs to develop their theorizing capabilities. Through an in-depth analysis of học tập phục vụ cộng đồng (service learning), it is possible to move beyond translation to theorizing. The analysis of another concept học dấn thân (service learning) provides resources for previously unseen considerations for theorizing [4]. Then, an analysis of the concepts used for service learning in Tiếng Việt media provides a focus for intercultural scholarly dialogues at the level of theorizing. The discussion section explores the importance of intellectual reciprocity in ISL through post-monolingual theorizing. The paper concludes by considering the possibilities of multilingual HDR’s intellectual resources for deepening their theorizing capabilities.

2. Theorizing Capabilities

While the concepts of “theorizing” and “theory” may be interpreted as interchangeable, they are actually different in nature. Theorizing focusses on the capabilities for building a theory, while theory is the product of this intellectual labor [8]. Developing theorizing capabilities is that part of the work of research that involves making “intelligible why people are saying and doing what they are saying and doing” [9] (p. 229). Two crucial capabilities required of researchers to engage in for theorizing are disciplined imagination [10,11] and creativeness [8]. This section elaborates on the capabilities researchers require for theorizing in order to better understand and to further clarify the challenging tasks multilingual researchers confront in extending their theorizing capabilities.

Following the agenda of Biesta et al. [9], developing one’s capabilities for theorizing may begin with speculative propositions about everyday experiences of ISL, for instance, in terms of making meaning of the relationships between power, knowledge, languages and gender. This step increasing one’s theorizing capabilities is the generation of explanations of the mechanisms and possible causative processes at work in ISL. These explanatory propositions are then tested against evidence to ascertain the potential empirical support for and credibility of these claims. It may be that the initial theorizing is misleading and has to be revised in the light of the evidence. This might be so even if the most recent, relevant research was used to inform initial theorizing. The ability to make such a judgement is an important capability a researcher has to achieve. In other words, a researcher has to recognize that the analysis and interpretation of the primary data collected to test one’s initial theorizing might give warrant for revisions. To minimize the vagueness about how to engage in and constitute a theory, the focus now turns to a logical and explicit explanation of the crucial capabilities required for theorizing.

Researchers have to have the capability to work with references, data, concepts and propositions. However, while these are necessary for theorizing, they are not sufficient. Thus, long reference lists are not evidence of theorizing. Although the capabilities for using these tools are integral to theorizing, theory production requires more work in terms of scholarship [12]. Theorizing requires researchers to have the capability to present “detailed and compelling arguments […] explicating the causal logic they contain” [10] (pp. 372–373). While being able to locate and give citations to scholarly literature in Vietnam on ISL may be necessary for Người Việt researchers, they are not sufficient for this task [13,14,15]. The challenge remains for researchers to develop the capabilities to advance credible with arguments through interesting theorizing.

Further, the capability for theorizing requires testing of analytical tools against data, but data by itself does not “constitute causal explanations” [10] (p. 374). Often empirical evidence is used to confirm or test an existing theory of ISL rather than being used to deepen researchers’ capabilities for generating new theoretical resources. In developing new theoretical tools, researchers demonstrate their capabilities for making sense of the data using concepts or images to “explain why empirical patterns were observed or are expected to be observed” [10] (p. 374). Of course, the language(s) in which data are collected should be represented in any reports to demonstrate the researcher’s multilingual capabilities; to enhance the credibility of the evidence and to make it available for re-analysis for those proficient in the language.

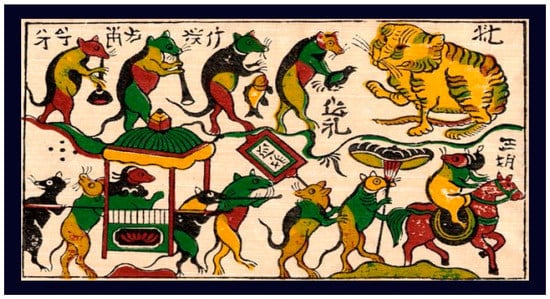

The capability for visual theorizing involves researchers generating images or diagrams to create an explanatory framework. To initiate the researchers’ development of their theorizing capabilities, diagrams can be used to illustrate the potential issues to be researched and be accompanied with an explanation and justification of the reasons for investigating a particular research problem from a specific standpoint [10]. Diagrams or images help readers envision the chain of causation being explained by researchers using a given theory. Visual aids which show causal relationships and logical order may be valuable in helping to clarify patterns and connections. For instance, the given image below of Đám cưới Chuột (Mice’s wedding) is an example of a wood-cut painting produced in Đông Hồ (Painting Village) in Vietnam (Figure 1). In this painting, some family members and/or guests of the bride and groom present gifts to a powerful cat, in an overture to prevent the bridal couple from being killed by the mouser. In terms of ISL, this image represents the negotiation of differential power/knowledge/language/gender relations. Those with limited power use their knowledge to soothe the dangers posed by powerful elites in order to carry on their lives. With regards to theorizing capabilities, the image might be reworked by a Người Việt researcher to schematically represent the cat as embodying the bureaucratic power revealed in the university administration procedures imposed on students, academic staff and partner organizations through ISL. If no resistance is made, academics have to negotiate this bureaucratic power as much as the demands of the students whose welfare and education they are working to support.

Figure 1.

Power/knowledge/gender relations in Dong Ho painting of Mice’s wedding.

While concepts are evidence of researchers developing capabilities for theorizing, a list of well-defined concepts or constructs “does not constitute a theory” [10] (p. 376). When generating and defining their own categories, researchers have to develop the capability to explain and justify the reasons for selecting and using specially designated concepts in their theorizing. The use of concepts from Tiếng Việt, for instance, might canvass the social-historical context of their production; what brings forward concepts from Tiếng Việt to be used as theoretical tools for their re-conceptualization; what forces constraint their use as theoretical tools; what challenges they pose by way of critique, and what intercultural intellectual connections their uses advances in the ISL field [16,17]. In Section 3 (Results), the concept of ISL is examined in terms of the conceptual divergences made possible by the Tiếng Việt.

Researchers’ theorizing capabilities extend to generating propositions to be investigated, subsequently revised and elaborated upon through the establishment of significant research findings. For Sutton and Staw [10] (pp. 376–377), these propositions are “concise statements about what is expected to occur” but do not in themselves constitute a theory. The theorizing capabilities of researchers involve the production of well-crafted conceptual arguments. In these conceptual arguments, key concepts along with logical arguments that justify and consider counterarguments are explicitly explained. Theorizing calls for researchers to have the capability to move from a preliminary sensitizing conceptualization of research problems to detailed, logical explanations of patterns or cause/effect relationships.

In sum, understanding the theorizing process is not easy. Moreover, actually carrying out the process of theorizing is a further challenge. Doing both of these in an academic language which is not one’s own is even more thought-provoking. Learning to theorize in one’s own language can be equally daunting. However, doing so is especially significant in terms of developing the capabilities for theorizing as well as for making an original contribution to knowledge through using one’s full linguistic repertoire. The following section explores the importance for multilingual researchers to develop their capabilities for theorizing using their full linguistic repertoire and to make original contributions to knowledge in such languages. The proposition investigated below (Section 3: Results) concerns the possibilities that multilingual HDRs might develop their capabilities for theorizing through using their full linguistic repertoire. If this proves possible through further research, then the conceptual divergences of Tiếng Việt may provide added values to theorizing ISL as a local/global phenomenon, and create the potential for constructing theoretical dialogues between intellectual cultures.

2.1. Partisanship and Reciprocity in Theorizing International Service Learning

ISL is a pedagogy for integrating academic knowledge and civic engagement activities located outside students’ nation-state. Thus, ISL brings to the fore issues of intercultural intellectual engagement. There has been increasing amount of literature discussing conceptual diversity through implementation, the attributes and issues of this field in education [18,19]. Bringle and Hatcher [20] (p. 19) define ISL in the following terms:

- have a structured academic experience in another country in which students;

- participate in an organized service activity that addresses identified community needs;

- learn from direct interaction and cross-cultural dialogue with others; and

- reflect on the experience in such a way as to

- gain further understanding of course content;

- a deeper understanding of global and intercultural issues;

- a broader appreciation of the host country and the discipline, and

- an enhanced sense of their own responsibilities as citizens, locally and globally.

Since the turn of the century, ISL has become a feature at higher education institutions around the world [13,14,15,21]. Pedagogically, integrating university students’ academic studies through ISL is seen as providing them with meaningful experiential learning while addressing community needs. Valuing the positive benefits of ISL for students, universities and community organizations, higher education institutions have begun to institutionalize this innovative mode of teaching/learning in their curricula. No precise concepts with commonly agreed meanings and characteristics reflecting all aspects of this educational pedagogy have been developed. This is because naming the field of service learning is contested. Ever more literature adds to Bringle and Hatcher’s [20] definition and provides insights into the scholarly conversations where the conceptualization of ISL is being debated. For instance, Hartman and Kiely [22] (p. 56) define the concept of global service learning (GSL) as developing “students’ intercultural competence through engaging with critical global civic and moral imagination” in the context of the “global marketization of volunteerism”. Claiming the debates over the concept of ISL, Mitchell [5] classifies the concepts dichotomously, one being “traditional” service learning and the other “critical” service learning. Traditional ISL aims at students’ personal development through challenging them with visions of life possibilities, while critical ISL brings into focus the structures of power and privilege, raising questions about how they might contribute to socioeconomic change. This critical conception of ISL is similar to that of Hartman and Kiely’s [22] definition. For Mitchell [5] (p. 51), the key component that affects ISL practice and policies is the “political nature of service” which means acknowledging “the imbalance of power in the service relationship, [while challenging] the imbalance and [redistributing] power through the ways that service-learning experiences are both planned and implemented” [5] (p. 57).

In contributing to the conceptual contestation in this field, Crabtree [23] (pp. 29–30) states that “ISL is about producing global awareness among all participants, providing opportunities to develop mutual understanding, and creating shared aspirations for social justice and the skills to produce it”. Niehaus and Crain [24] (p. 32) argue that this debate over ISL concepts is compounded because there is “little research directly comparing international and domestic service-learning, most of this evidence comes from the larger study abroad literature”. Moreover, McCarthy et al. [25] (p. 2) contend that parochialism has a negative impact on conceptualization of the field, insofar as “ISL generally remains a less well developed area of concern in the USA”. Therefore, there is a need to analyze the place of theoretical reciprocity and partisanship in ISL.

For the reasons of social justice, reciprocity [20,26] is important for ISL when working with international community partners and participants. For instance, Bartleet et al. [27] propose a framework that makes reciprocity central to ISL partnerships and research. Minimally, reciprocity means ISL projects work respectfully with international partner organizations and communities. Likewise, Halimi et al. [14] argue for fully reciprocal relationships in co-creating ISL knowledge and practices. In a similar study, Basel [21] reports that the very continuation of ISL endeavors occurs because of the reciprocity international partner organizations and communities with the university, academics and students with whom they work. However, as Tranviet [15] found stakeholders’ perceptions, experiences and conceptions of reciprocity are shaped, constrained and enabled by (a) socio-economic and cultural differences; (b) historical legacies and personal backgrounds; (c) program location; and (d) country-to-country dynamics. These factors shape how different actors understand their own benefits and those of other stakeholders.

There are problems and tensions in terms of the reciprocal versus the partisan benefits of ISL. ISL is a structured academic experience undertaken in another country. This raises questions about what scholarly dialogues are occurring across intellectual cultures that might enhance the appreciation of the people from that country for making meaning of ISL. That in turn leads to the question of just how “international” ISL is [15] when it is mainly theorized using just one language (i.e., English). What are the possibilities for theoretical reciprocity in a field that claims to be “international” or “intercultural”? Let us briefly interrogate whether ISL theorists present evidence of engaging in theoretical dialogues across languages and intellectual cultures about ISL.

Bringle et al. [20] provide a conceptual framework for ISL that draws on knowledge from service-learning and community engagement programs in the USA. Their study does include a South African theorization of ISL interventions. However, overall its theorizing is partisan, contained only within US academic knowledge and the English language. For ISL, to gain credibility, there is the need to build closer intellectual connections with those who act as intentional community partners, to work with their theorizations of the field. This is especially significant if notions of intercultural mutuality and the value of listening are to have any substantive scholarly value.

Consider for a moment of Crabtree’s [23] argument that because ISL is a multifaceted endeavor, its theoretical foundations should be informed by multiple disciplinary and interdisciplinary literatures. Crabtree [23] reports that intellectuals from “southern” nations theorized ISL in relation to sustainability, democratization, biodiversity, Indigenous people’s rights, gender, race, and (im)migration. Porter and Monard’s [28] applied the Andean concept of Ayni (reciprocity) to analyze what a shared understanding of sustainable development might mean, and argued for developing students’ relational and equitable theorization of ISL. However, Crabtree [23] concludes that few ISL educators engage the theories and models of ISL developed in the international intellectual cultures where these programs are conducted. For Crabtree, this partisan, US-centric tendency for theorizing ISL is “particularly troubling in the case of ‘international’ service learning” [17] (p. 22). More research is needed to better understand the possibilities, dynamics and effects of building on existing interdisciplinary theoretical frameworks for ISL to using conceptual tools from the divergences of languages where these projects are undertaken to theorize ISL. This would go some way to give ISL a substantive “international” scholarly dimension.

2.2. Reciprocity in ISL Theorizing

To honor reciprocity in ISL, it would be meaningful for multilingual researchers to use their full linguistic repertoire to engage in theorizing ISL [7]. In this paper, reciprocity in theorizing [7] assumes that the constitution of conceptual framework for ISL is likely to benefit from engaging with the conceptual divergences of within/between the languages of project participants. In this way, ISL is defined as a field that, among other things constructing theoretical dialogues between intellectual cultures, even though experiencing the monolingual press for English medium instruction research and theorizing [29].

This is a very challenging task for all researchers involved in ISL, monolingual and multilingual researchers alike. For multilingual HDRs who speak Tiếng Việt, doing their doctoral research in a university which takes English-only research and education for granted, they expect to start their research career as intellectual inferiors who must learn existing theories available in English. They have no expectations that they might make an original contribution to knowledge, certainly not a contribution which uses Tiếng Việt to generate resources for theorizing. Moreover, because of the privileging of English-only monolingualism in the universities in which they are studying, both their diverse linguistics capabilities and the theoretical resources available in these are ignored. Both English and theories in English have a taken-for-granted privilege. The path multilingual HDRs travel to develop their theorizing capabilities presents many difficulties. These challenges include initiating the writing of Tiếng Việt ideas as if they could be used analytically, as well as facing “conflicts and contradiction” [10] (p. 372) from both monolingual and multilingual research communities. Support for multilingual researchers to engage these is necessary to build their self-confidence in using their intangible assets, their intellectual cultures and languages as resources for generating theoretical tools. As early career researchers, multilingual HDRs need the awareness and reassurance of supportive research educators so they can make an original contribution to knowledge by bringing forward theoretical assets from their complete linguistic repertoire [29]. Thus, it is very important that English-speaking monolingual researchers help their multilingual research colleagues in overcoming the anxiety of being alone in developing their theorizing capabilities and in building any credible and worthwhile theoretical resources from Tiếng Việt.

Not all multilingual HDRs have the will to engage in such a challenging undertaking. With the rise of English as the global language of research, such intellectual engagement requires bravery or foolishness [1]. Those HDRS who take up this challenge have to be prepared for the pain of arduous intellectual labor inherent in a theorizing process and the injury associated with the trials and errors of supervisors’ feedback and peer reviews [30]. Specifically, theorizing is a time-consuming and energy-intensive process. Moreover, it may end with the failure to meet the strict criteria of highly reputed journals. Multilingual HDRs may be discouraged because “even when a well-articulated theory that fits the data, editors or reviewers may reject it or insist the theory be replaced simply because it clashes with their particular conceptual tastes” [10] (p. 372). Multilingual HDRs have to have good strategies for disseminating the theorizing they produce because “without publications, that scientist’s work will have been largely wasted” [31] (p. 390). So what might make it worthwhile for multilingual HDRs to engage in the challenges of theorizing by using their intellectual resources from multiple languages? Without such capabilities, Tiếng Việt and Người Việt intellectual culture(s) will continue to be data collection sites, merely providing evidence to be tested using theories generated in English [29]. For HDRs who speak Tiếng Việt, it is important that they develop the capabilities required for theorizing in this language in order to:

- improve ISL programs in the Người Việt communities with which they work;

- better understand what theory is; and

- use Tiếng Việt for the higher order intellectual work of theorizing [7].

This important scholarly debate in the field of ISL gives warrant to further investigation of multilingual HDRs’ uses of theoretical resources from their full linguistic repertoire in the research and education they undertake in universities that privilege English and theoretical knowledge in English. In order to address this research problem, key concepts from Jullien’s [4] research are used for analyzing ISL as expressed in Tiếng Việt concepts. For Jullien, the conceptual divergences within and between languages open up possibilities for new thoughts, including alternatives for theorizing ISL. In other words, conceptual divergences within Tiếng Việt and between it and English gives multilingual HDRs a new lens to explore and deploy in making sense of real world ISL programs. This means moving beyond employing existing theories of ISL such as those of Bringle, Hatcher and Jones [20] in expected, ordinary and predictable ways. In research, languages are often presented as barriers. Translation is used to transfer evidence generated in one language (e.g., Tiếng Việt) to another (English), wherein it is theorized. Thus, translation “does not in itself say everything” regarding the intellectual matter exchanged “between languages” [4] (p. 82).

In contrast to translation, the capability for theorizing entails exploring the conceptual divergences within/between language(s) by crossing the frontiers of language [4] (p. 49). Theorizing through the conceptual divergences of language requires the elaboration and in-depth re-examination of concepts in other languages to make explicit their theoretical value or otherwise explicit. The concept of “divergence within/between language(s)” invites multilingual HDRs to explore “the unthought” in our linguistic repertoire, the unthought in our theorizing [4] (pp. 118, 120), and then to create “conditions for an intelligent dialogue, between [intellectual] cultures” [4] (p. viii). Accordingly, the following section provides a brief explanation and justification of the method used in the research reported in this paper. In particular, it focuses on the analytical tools used to make meaning of the possibilities for theorizing ISL using Tiếng Việt. The analytical lens employed in this study uses the conceptual divergences within Tiếng Việt, and between Tiếng Việt and English to elaborate or otherwise elongate the conceptualization of ISL [4].

2.3. Research Method

Employing “post-monolingual research methodology” [32,33] enables multilingual HDRs to explore possibilities for extending their capabilities for theorizing by using their full linguistic repertoire and thereby perhaps making original contributions to knowledge by formulating novel analytical tools. This study aims to establish a scholarly relationship between selected concepts or images in one language (Tiếng Việt) and another language (English) as a means for considering possibilities for theorizing ISL [29]. This entails exploring the conceptual divergences within/between of languages in the use of the concept service learning in Tiếng Việt and English. Through further research, such theorizing may enable the future production of analytical concepts used that can then be to formulate novel propositions about ISL [7,34]. To do so, the concept of divergence within/between languages [4] is used as a tool to analyze previously unthought possibilities for theorizing in Tiếng Việt as a basis for further work in the field of ISL. Importantly, this study indicates that post-monolingual theorizing can be undertaken universities which privilege English-only monolingualism [29].

For the purpose of this case study, evidence of Tiếng Việt concepts from three universities represent instances of the larger phenomenon of theorizing ISL in Tiếng Việt. This case study addresses the following research questions:

- Might the term used by Vietnamese universities for service learning open up possibilities for theorizing?

- Is it possible to move beyond translating English concepts for service learning to use Tiếng Việt for developing theorizing capabilities?

- Might concepts in Tiếng Việt about service learning reveal previously unheard of possibilities for theorizing?

- Might concepts in Tiếng Việt about service learning provide a focus for intercultural dialogical theorizing?

The data set for this study includes the Tiếng Việt names used by universities and the media in Vietnam for service learning subjects/courses. Of the 412 higher education institutions in Vietnam, three universities were found implementing service learning programs, namely, Hoa Sen University, Ho Chi Minh City University of Social Sciences and Humanities, and Ho Chi Minh City University of Science [35,36,37]. On their websites, these three universities claim that their service learning programs are the first to be embedded in curriculum in Vietnamese higher education system. The term service learning was used in Vietnam based on the philosophy of education and pedagogy from the USA as an expression of internationalization of education. The concept Học tập phục vụ cộng đồng is the standardized Tiếng Việt translation of the English term “service learning”. For these three universities, service learning is an innovative educational approach to engage students in real-world learning experiences and prepare them for international citizenship. Students’ contributions to the community inform their higher education studies and enhancing their employability.

A list of various concepts used by the Vietnamese media (n = 2) for service learning programs was also created. The websites were selected because they give focused, relevant concepts and information about service learning in Vietnam. These websites are the online newspapers and the media channels in Vietnam which report news and publish official reports on social issues and current affairs. The list of concepts for service learning offers insights into divergences in Tiếng Việt, moving beyond its familiar translation from English.

Data were analyzed using the process of evidentiary conceptual unit analysis [38] (p. 182). This process began by selecting the Tiếng Việt concepts for ISL as the evidentiary unit. Conceptual commentaries were generated to analyze or otherwise explain or make meaning of the data. This key concept was then used to generate a conceptual statement to introduce and focus on the evidentiary unit of conceptual analysis. Orienting information was provided to contextualize the data sources. In this way, each of the following four evidentiary units of conceptual analysis has been crafted to explain and justify the interpretation made of the evidence.

3. Results

Theorizing ISL using Tiếng Việt concepts proved to be a messy process of trial-and-error in which the concepts were interrogated, refined, elaborated and repolished. Lists, typological categories, and diagrams were used to aid the conceptualization of evidence-based logical explanations presented below [13]. To sharpen the theorizing undertaken here the conceptualization of the evidence has been stretched through reasoned arguments which have been further extended with the explicit use of citations to relevant references. All of this is integral to building the capabilities required for reciprocal rather than partisan orientation to theorizing of ISL.

3.1. Divergence of Language

As noted above, there is no lack of different ways of defining service learning in English. Service learning is a much-contested concept. Each definition of service learning is supported by informed arguments and credible evidence, providing little grounds for resolving these debates given the reasonable grounds for these disagreements. Understanding that service learning is a contested concept is useful for multilingual HDRs who are confronted with the challenge of finding ways to make familiar or taken-for-granted notions of service learning strange in order to make an original contribution to knowledge. This perspective makes it possible for multilingual HDRs to look beyond the predictable debates over service learning in English, by using their full linguistic repertoire to detach their theorizing from expected ways of reading notions of ISL in order to leverage new insights.

To investigate other possibilities for understandings of ISL, multilingual HDRS can explore the conceptual divergence within/between languages so as “to probe where these singularities can go and what by-ways they open up in thought” [4] (p. 147). The concept “divergence within/between of languages” is used here to open up possibilities for seeing ISL in a new light, and to reveal other possibilities for understanding ISL. Divergence within/between languages allows theorizing of ISL in ways that move beyond the mere translation of service learning from English into Tiếng Việt. The three universities mentioned above, namely, Hoa Sen University, Ho Chi Minh City University of Social Sciences and Humanities and Ho Chi Minh City University of Science use the term học tập phục vụ cộng đồng for service learning subjects/courses. “The expected, the ordinary and the predictable” [4] (p. 147) understanding of ISL is the translation of this concept as học tập phục vụ cộng đồng, making the Tiếng Việt equivalent to the English term. However, a divergence between these languages is evident in the use of two words in English for this concept while it takes six words in Tiếng Việt. Thus, there is more at stake here than the mere translation of an English concept into a Tiếng Việt concept. Table 1 below provides an in-depth analysis of học tập phục vụ cộng đồng. Theorizing goes beyond translation techniques for moving a concept from one language to another. Recognizing this opens up possibilities for seeing ISL in a new light, for understanding ISL from different perspectives. Rather than being fixed by translation through the “reign of uniformity” [4] (p. 14), theorizing broadens the resources available for making meaning of ISL. Attending to the divergences between ISL and học tập phục vụ cộng đồng offers possibilities for theorizing which tended to be ignored through a focus on the standardization effected through translation. I struggled to detach myself from expected ways of translating the notion of ISL into Tiếng Việt. Gradually, meaning of the divergence within/between languages itself came into focus making it possible to analyze the conceptual divergences between the English and Tiếng Việt concepts, opening up small but possibly significant new understandings of ISL.

Table 1.

In-depth analysis of Tiếng Việt concept Học tập phục vụ cộng đồng (service learning).

3.2. Beyond Translation to Theorizing

For Jullien, “to translate is to think [and] to think is always also to translate” [4] (p. 164), here, translation is understood as a mechanism for moving towards post-monolingual theorizing, and post-monolingual theorizing is a way to move beyond translation. Unlike translation, theorizing is not a matter of conversion between languages. Theorizing goes beyond translation to forming and informing concepts from communicating across intellectual cultures. In other words, theorizing requires more than transferring language “content according to other, notional and syntactical, expectations, crossed the frontiers of the source language, taking its universalization with it” [4] (p. 49). In contrast, theorizing gains its significance when used to engage in intercultural educational dialogues. Table 2 shows that the Tiếng Việt concept học (learn) can be translated into three categories of meaning in English. One strand of học focuses on learning and enquiry; the second on imitating, following a good example or receiving teaching/education, and the third strand focuses on study and research. Of course, the list of meanings attributed to “service learning” presents challenges which do not only apply to Tiếng Việt and/ or do not only occur because of translation [10]. However, the focus of this study is not on the contested meaning of this “service learning”. Instead, the focus is on exploring the capabilities required for theorizing ISL using Tiếng Việt concepts.

Table 2.

In-depth analysis of Học dấn thân (engaged learning).

Table 1 indicates that the potential for learning (học) through serving (phục vụ) is variable and complicated. The concept of phục vụ (serve) can speak to the ideology of serving according to different societal interpretations. For some, serving may a part of people’s work whereas for others there may be a hierarchical divide between working and serving. Working (làm việc) is seen as making a societal contribution, while serving (phục vụ, hầu hạ) is held in lower status and undeserving of honor. The three contrasting features of học (learn) open up to question the concept of ISL, and understandings and uses of it in Vietnam and other epistemic communities. Even though these three strands have tập (practice) as a key component, in some ISL programs, students’ learning resides in imitating a good example whereas learning process in some long-term ISL programs take place through research. In the first and second strand, phục vụ (serve) means to do someone’s own work, while cộng đồng (community) means all groups working together. In the third strand, the terms phục vụ (do work that benefits others) and cộng đồng (adding the things held in common) have different meanings from the other two strands. Learning and serving can be linked by more than one channel driven by curriculum requirements or social responsibilities to the local community or to the nation. Read through the perspectives of intellectual culture, linguistics, nation and ideology, such theorizing brings forward possibilities for a new understanding to ISL that is rooted in this Tiếng Việt concept itself. Thus post-monolingual theorizing of ISL means going beyond translation techniques of converting “between the languages” to focus on theorizing “between thoughts” [7] (p. 182) in other languages.

3.3. Resources of the Unthought

Resources of unthought reside in establishing the angle of difference and from disagreement. Here is an opportunity for multilingual researchers to engage in “comparison to the thought of other cultures” [4] (p. 6). For Jullien [4] (p. 6), the resources of the unthought are to be found on “the flip-side of the uniform”. The concept of học dấn thân (engaged learning) (Table 2) is used by Hoa Sen University to explain and promote its service learning program. Table 2 provides an understanding ISL or học dấn thân using Tiếng Việt theoretic-linguistic tools. It indicates that there is no necessary uniformity regarding what this concept means or how it is used in Tiếng Việt.

The Tiếng Việt resources for theorizing ISL in terms of học dấn thân (engaged learning) have potential for exploring the conceptual divergences of what had previously not been thought of as analytical tools. If the word order is turned around to read thân dấn học, ISL begins with thân (body) which foregrounds the labor used in this kind of experiential learning method. Dấn (engage) expresses the eagerness and enthusiasm for doing these tasks. Learning (học) is expected to occur before, during and after the time serving takes place. To be engaged in community service activities, students start learning by imitating the labor of others. Learning from labor might affect students’ freedom to choose serving and/or learning. Exploring the “unthought” provides the potential to theorize ISL in terms of the relation between students’ labor and those who benefit from their services in this process. For researchers, this raises the question of how labor capability is to be measured and directed towards productive service and learning. Multilingual HDRs can look for theoretical resources in the languages they use by exploring the conceptual divergences of language for evidence of the unthought.

3.4. Conceptual Divergences within one Language: Intercultural Dialogues

Different from the conceptual divergences between languages in English and Tiếng Việt for service learning and học tập phục vụ cộng đồng, Table 3 shows the divergences of the uses and ways of viewing service learning in the same language, Tiếng Việt. The divergences of concepts of service learning used in Table 3 help us figure out the possibilities of intercultural dialogues in this field. Intercultural dialogues in ISL challenge both educators and researchers due to the pluralism of educational cultures. From a post-monolingual perspective, the concept “intercultural dialogues” is grounded in the reality that “dialogue has never been as egalitarian and neutral as has been sanctimoniously claimed [due to inequitable] power relations” [4] (p. 160). Here the aim is to “enable communication [and] gain a focus” (p. 160) that can advance intercultural intellectual dialogues. The Vietnamese media used two concepts to refer to service learning học dấn thân and học tập phục vụ cộng đồng.

Table 3.

Tiếng Việt concepts for service learning in Vietnamese media.

Table 3 invites the questions whether the concepts of Học dấn thân and Học tập phục vụ cộng đồng might be understood as representing and expressing two educational cultures. If so, what can be done to avoid the possibilities that when ISL takes place, “this plurality of cultures is designated as a new (and principal) source of conflicts in the world to come” [4] (p. 157)? Reaching a consensus in intercultural dialogues about ISL now seems to be inadequate to deal with variations among intellectual cultures within and across nations. Communication may sometimes be driven by tensions. Conflict may occur. Disputes and differences between educational cultures necessitate “a protocol of dialogue” [4] (p. 131). The implementation of protocol for intercultural dialogues about ISL that is egalitarian may be weakened by the dominating intellectual culture. The challenge to balance intercultural dialogues among intellectual cultures might help open up other possibilities. The next section discusses further the usefulness of the method for theorizing ISL illustrated here.

4. Discussion

This paper has used Jullien’s [4] concept of “divergence of language” to open up the possibilities for theorizing ISL in the Tiếng Việt language. The contribution of this paper has been using “divergence of language [to explore] the extent to which other paths can be cleared” [4] (p. 147) for theorizing. The mystification of theory and theorizing may create negative of thoughts about them. The process of theorizing presented in this paper shows these assumptions are false. The above analysis indicates that within the Tiếng Việt, there exists a rich diversity of intellectual resources for theorizing ISL. This gives substance to Jullien’s [4] (p. 143) claim that any intellectual culture always exists only as a diversity of intellectual cultures. The use of Tiếng Việt concepts to theorize ISL indicates the language’s pluralism, as much as the intellectual culture of which it is a part. Moreover, for multilingual researchers, engaging in “post-monolingual theorizing” [7] in Anglophone universities brings to the fore their linguistic repertoire and diverse intellectual resources while marking a considerable change from English-only uniformity that currently obstructs original knowledge production.

The paper has explored the divergence of language to theorize ISL. It has shown that Tiếng Việt can be used as an intellectual resource for theorizing, and as a mechanism for developing multilingual researchers’ capabilities for theorizing. Theorizing is an important, complicated academic work that leads to conceptual tools that are not just original but provide novel, meaningful insights. However, current scholarly contributions to debates in the field of ISL do not address the question of theorizing using intellectual resources from other languages rather English [8,10,11,12]. Of course, theory building requires the investment in existing theoretical scholarship. To make such “post-monolingual theorizing” intelligible means to build evidence reporting on the use of conceptual divergences of languages for theorizing ISL, and justifying the added value gained through these theoretical tools [4]. The divergence of language explored in this study opened up taken-for-granted readings of Tiếng Việt conceptions of ISL as học tập phục vụ cộng đồng as in imitate (bắt chước), practice (tập) and do someone’s own work (phục vụ) and of all groups (cộng đồng). This research into the divergence of language indicates potential alternatives for theorizing ISL, such as receiving teaching/education (thọ giáo); doing work of lower status and undeserving of honor (phục vụ) and adding to what is common (cộng đồng).

Such theorizing was not possible until I analyzed in-depth the concepts of service learning in both English and Tiếng Việt. I had not thought of doing before I engaged with the literature on post-monolingual theorizing [33]. The insights gain through theorizing ISL using the divergence of languages brought to the fore the ideologies in this field in which students may be passive learners waiting for their knowledge givers through to active engagement in initiatives with hierarchical relationships of power/knowledge in working and serving. The question this study raises is whether ISL can be “international” if only certain nations (e.g., the USA, the UK) get to theorize about the field in their language (e.g., English). A related question is what is required to make Tiếng Việt concepts part of the international theorizing of ISL. ISL is an innovative approach to experiential education that entails the power/knowledge relations which are also gendered. Some research fails to address this issue [18,19].

Moreover, this paper indicates that multilingual researchers can explore and deploy their repertoire of linguistic resources to develop their capabilities for theorizing. Not all multilingual researchers are aware of, or can make an advantage of their complete linguistic repertoire for theorizing. For instance, rather ironically, research into multilingual issues by Vietnamese scholars does not use Tiếng Việt as an intellectual resource for theorizing these issues [44,45]. Singh [7] observes that any reluctance by multilingual researchers may be due to not wanting to confront the pain being of having their efforts at post-monolingual theorizing rejected by examiners, editors or reviewers. The intellectual contribution multilingual researchers can make to post-monolingual theorizing [33] requires will, enthusiasm and determination to engage in such an adventurous, perhaps even risky journey. This paper indicates that by exploring the divergence of language, these researchers may deploy and develop their multilingual skills for deepening their theorizing capabilities in educational research.

5. Conclusions

It is fascinating to consider the important question of the divergence of languages as potential resources for theorizing. While English might be necessary for theorizing about ISL, it hardly seems to be sufficient in this age of global education. The study explored the possibilities of theorizing ISL through investigating the potential of the conceptual divergences of languages in Tiếng Việt and English. This entailed analysis of English and Tiếng Việt concepts of ISL. The findings indicate that there are conceptual divergences within and between these languages which provide openings for theorizing ISL. I had ignored these possibilities for developing my research capabilities due to being strongly wedded to English-only monolingual theorizing. Like other multilingual researchers, I had not thought “outside the box” as a result of my taken-for-granted perspective using existing theories in English as a means of knowledge production. Like some multilingual researchers, I was not confident about engaging in theorizing, or using my linguistic repertoire as resources for theorizing. Fortunately, this study of the conceptual divergences of languages revalues Tiếng Việt as a potential vehicle for contributing to the production of original theoretical knowledge about ISL. However, these by themselves do not make a theory; more research remains to be done in this regard.

As with all research, this study has some limitations. This case study analyzed evidence of concepts from three ISL programs at universities in Vietnam. Further research across more universities in Vietnam is warranted. This study has indicated the value of exploring the possibilities of languages offer by way of resources for theorizing. The concepts employed in this study are from Tiếng Việt and English. Further research might generate theoretical sources through other languages to test tools for the conceptual analysis of ISL in a range of settings. The study has implications for multilingual education and multilingual researchers. In terms of multilingual education, universities might consider policies and curricula that enables and encourages Higher Degree Researchers to develop their academic multilingualism. This might help them maximize the possibilities of learning through using their linguistic repertoire. With regard to multilingual researchers, they might make use of their linguistic repertoire for making original contributions to theoretical knowledge. Multilingual researchers may develop their capabilities for theorizing as important opportunities for extending their scholarship in education or their employability in international partnerships. Such researchers may use their full linguistic repertoire to sharpen their capabilities for theorizing in research. Therefore, theorizing ISL might be based on international perspectives that add to scholarly debates in this field.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Michael Singh for encouraging me to engage in Multilingual Research. His useful and valuable advice helped me develop the research skills and theorizing process that are reflected in the paper. This research was financially supported by Western Sydney University and Vietnam International Education Development (VIED).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Singh, M. Pedagogies of intellectual equality for connecting with non-Western theories. In Precarious International Multicultural Education; Wright, H., Singh, M., Race, R., Eds.; Sense: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Shahjahan, R. International organizations (IOs), epistemic tools of influence, and the colonial geopolitics of knowledge production in higher education policy. J. Educ. Policy 2016, 31, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, W.; Çelik, E.; Wöhrer, V. (Eds.) Global Knowledge Production in the Social Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2016.

- Jullien, F. On the Universal, the Uninform, the Common and Dialogue between Cultures; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T. Traditional vs. critical service-learning: Engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Mich. J. Commun. Serv. Learn. 2008, 14, 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gallie, W. Essentially contested concepts. Proc. Aristot. Soc. 1955, 56, 167–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Worldly critical theorizing in Euro-American centered teacher education? In Global Teacher Education; Zhu, X., Zeichner, K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- Swedberg, R. Before theory comes theorizing or how to make social science more interesting. Br. J. Sociol. 2016, 67, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biesta, G.; Allan, J.; Edwards, R. The theory question in research capacity building in education. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2011, 59, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.; Staw, B.M. What Theory is Not. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K. What Theory is Not, Theorizing Is. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroløkke, C. What is the obligation to build theory? West. J. Commun. 2013, 77, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghee, W.; Zakaria, F.; Zain, W. Promotion of Civic Engagement through a Service Learning Experience: A Community-Based Intercultural Leadership Program in Vietnam. In Proceedings of the University-Community Engagement Conference for Empowerment and Knowledge Creation, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 9–12 January 2012.

- Halimi, S.; Kecskes, K.; Ingle, M.; Phuong, P. Strategic international Service-Learning Partnership: Mitigating the Impact of rapid Urban Development in Vietnam (46–67). In Crossing Boundaries: Tension and Transformation in International Service-Learning; Green, P., Johnson, M., Eds.; Stylus Publishing: Sterling, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tranviet, T. Examining benefits in international service learning from comparative perspectives: A Case Study of the Suny-Brockport Vietnam Program. Ph.D. Thesis, State University of New York System (SUNY), Albany, NY, USA, 24 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Chen, X. Ignorance and pedagogies of intellectual equality. In Reshaping Doctoral Education; Lee, A., Danby, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Huang, X. Bourdieu’s lessons for internationalising Anglophone education: Declassifying Sino-Anglo divisions over critical theorising. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2013, 43, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butin, D. Service-learning in Theory and Practice: The Future of Community Engagement in Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Deeley, S. Critical Perspectives on Service-Learning in Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bringle, R.; Hatcher, J.; Jones, S. (Eds.) International Service Learning: Conceptual Frameworks and Research; Stylus Publishing, LLC: Sterling, VA, USA, 2012.

- Basel, C. Double Happiness: Secondary School Students’ Experiences of Community Service-Learning in an International School Offering the International Baccalaureate Programme in Vietnam. Master Research Thesis, Melbourne University, Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, E.; Kiely, R. Pushing boundaries: Introduction to the global service-learning special section. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2014, 21, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, R. Theoretical foundations for international service-learning. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2008, 15, 18–36. [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus, E.; Crain, L. Act local or global? Comparing student experience in domestic and international service-learning programs. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2013, 20, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, F.E.; Murakami, M.; Nishio, T.; Yamamoto, K. Crossing borders at home and abroad: International service learning and the Service Learning Asia Network. In Proceedings of the 6th International Service Learning Research Conference, Portland, OR, USA, 27 January 2006.

- Keith, N. Community service learning in the face of globalization: Rethinking theory and practice. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2005, 11, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bartleet, B.; Bennett, D.; Marsh, K.; Power, A.; Sunderland, N. Reconciliation and transformation through mutual learning: Outlining a framework for arts-based service learning with Indigenous communities in Australia. Int. J. Educ. Arts 2014, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.; Monard, K. Ayni in the global village: Building relationships of reciprocity through international service-learning. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2001, 8, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M. Multicultural international Mindedness: Pedagogies of intellectual e/quality for Australian engagement with Indian (and Chinese) theorising. In Proceedings of the Multiculturalism: Perspectives from Australia, Canada and China, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 21–22 November 2011; pp. 94–105.

- García, O.; Wei, L. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clapham, P. Publish or Perish. Bioscience 2005, 55, 390–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. ‘Other thoughts’ to guide research educators, candidates and managers. Educ. Philos. Theory 2016, 48, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Learning from China to internationalise Australian research education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2011, 48, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Designing research to improve students’ learning. Aust. Educ. Res. 2013, 40, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa Sen University. Available online: http://www.hoasen.edu.vn/en/15733/about-us/center-service-learning (accessed on 16 September 2016).

- Social Sciences and Humanities University. Available online: http://rls-sea.de/blog/tag/ussh-hcmc/ (accessed on 16 September 2016).

- Ho Chi Minh University of Science. Available online: http://web.hcmus.edu.vn/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=7040&Itemid=1327 (accessed on 16 September 2016).

- Emerson, M.; Fretz, R.; Shaw, L. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyên, M. Ra mắt mô hình “Học dấn thân” đầu tiên tại Việt Nam. Bao Moi. 2015. Available online: http://www.baomoi.com/ra-mat-mo-hinh-hoc-dan-than-dau-tien-tai-viet-nam/c/16359772.epi (accessed on 16 September 2016).

- Lịch, N. Ra mắt mô hình học tập mới: Học dấn thân! Thanh Niên Online. 2015. Available online: http://thanhnien.vn/gioi-tre/ra-mat-mo-hinh-hoc-tap-moi-hoc-dan-than-549815.html (accessed on 16 September 2016).

- Nguyên, M. Ra mắt mô hình “Học dấn thân” đầu tiên tại Việt Nam. Ha Noi Moi. 2015. Available online: http://hanoimoi.com.vn/Tin-tuc/Huong-nghiep/748658/ra-mat-mo-hinh-%E2%80%9Choc-dan-than%E2%80%9D-dau-tien-tai-viet-nam (accessed on 16 September 2016).

- Tâm, M. Học để phục vụ cộng đồng. Giao duc. 2009. Available online: http://www.giaoduc.edu.vn/hoc-de-phuc-vu-cong-dong.htm (accessed on 16 September 2016).

- Phan, P. Học ở người nghèo, học từ cộng đồng. Tuoi Tre. 2014. Available online: http://tuoitre.vn/tin/tuoi-tre-cuoi-tuan/20140713/hoc-o-nguoi-ngheo-hoc-tu-cong-dong/621319.html (accessed on 16 September 2016).

- Nguyen, H. The multilanguaging of a Vietnamese American in South Philadelphia. Univ. Pa. Work. Pap. Educ. Linguist. 2012, 27, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tuc, H.D. Vietnamese-English Bilingualism: Patterns of Code-Switching; Taylor & Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).