Abstract

Based on a three year action research project, this study examines one strand of that research, namely the impact that ‘purpose’, i.e. exploring the range of rationales for studying a subject, has in helping white trainee teachers embrace cultural and ethnic diversity within their teaching. Through ‘purpose’ trainees explored different reasons why history should be taught (and by implication what content should be taught and how it should be taught) and the relationship of these reasons to diversity. Focusing on ‘purpose’ appears to have a positive impact on many trainees from white, mono-ethnic backgrounds, enabling them to bring diversity into the school curriculum, in this case history teaching. It offers one way to counter concerns about issues of ‘whiteness’ in the teaching profession and by teaching a more relevant curriculum has a potential positive impact on the achievement of students from minority ethnic backgrounds.

1. Introduction

This study focuses on supporting trainee teachers on a one year history initial teacher education (ITE) program (known as a Postgraduate Certificate in Education or PGCE) in England in their attempts to include greater diversity in their teaching in high schools; in other words, trainee teachers should regularly be able to find ways to integrate diversity into the curriculum they teach, which would be done in a meaningful and sensitive fashion, rather than as a tokenistic measure. The study arose out of concerns that trainee teachers and teachers from the dominant social group often find it difficult to teach a curriculum that includes material which covers a diverse range of social groups, even though societies are multi-ethnic and multicultural. This paper addresses one aspect of a three year study, namely the extent to which a focus on the purpose of teaching curricular topics could change the beliefs, values and actions of trainee teachers so that they teach a more diverse curriculum.

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

In this section I start by exploring what is meant by diversity before explaining why there is a particular focus on cultural and ethnic diversity in this study. This leads into a discussion about the place of diversity within the history curriculum generally and concerns about the dominance of a mono-ethnic history curriculum, which is seen in many countries [1,2,3,4], and the disengagement of some students from minority ethnic backgrounds. This is followed by a discussion of broad concerns about the nature of the teaching population and how teacher educators have tried to shape the ideas, attitudes, beliefs and actions of trainee teachers. The section concludes with a discussion of different purposes for teaching history and the relationship of these to a diverse history curriculum.

2.1. Diversity in the Curriculum

Diversity as a concept is a contested notion, covering a range of possible differences between individuals and groups and also differences within groups. It is therefore a complex term and open to dispute [5,6]. At one level diversity reflects the complexity of society and the different groups within a society, yet the notion of a group is also a construct and which may be rejected by individuals assigned to specific groups. In England, diversity is defined broadly within official government documents; for example in the history National Curriculum which exists in England, [7] it states:

Cultural, ethnic and religious diversity: Pupils should explore cultural, ethnic and religious diversity and racial equality. Diversity exists within and between groups due to cultural, ethnic, regional, linguistic, social, economic, technological, political and religious differences. Cultural understanding should be developed through the range of groups and individuals investigated, for example minorities and majorities, European and non-European. People and societies involved in the same historical event may have different experiences and views and may develop a variety of stories, versions, opinions and interpretations of that event.

For the purpose of this study the focus was on cultural and ethnic diversity; although this reflects a narrow aspect of diversity, the National Curriculum in England has often been criticized for failing to address cultural and ethnic diversity effectively [6].

This lack of cultural and ethnic diversity is not unique to England and is seen as a factor in the disengagement and relative underachievement of some students from minority ethnic backgrounds [8,9,10]. Where curricula have better reflected the cultural and ethnic diversity of society there have been positive outcomes in terms of student engagement and attainment from minority ethnic students [11,12].

A lack of cultural and ethnic diversity does appear to be a concern within the area of history education generally. Clearly history is a construct, and as such the history that is written about and taught often reflects particular values and viewpoints. History can be used to ignore or explore a diverse past. It has therefore been seen as an important means of teaching a more inclusive and diverse view of society [13,14,15], as it enables students to examine the range of experiences of people in the past and the contribution and struggles of individuals and different groups to the development of contemporary society, as well as having a strong role in the formation of identity and sense of belonging [16]. Banks [17] argues that diversity needs to be at the heart of any curriculum, yet sees history as having a particularly important role.

Within England the evidence shows that the history curriculum has limited appeal to students from minority ethnic backgrounds. A report for the Department for Education and Skills [18] identified pupils’ favorite and least favorite subjects. History did not feature in anybody’s list of favorites but was cited frequently as a least favorite subject amongst pupils from minority ethnic backgrounds. A study by Grever, Haydn and Ribbens [19] would suggest that this is due to the content within the curriculum. Their study, based on a survey of over 400 pupils aged 15–18 in the Netherlands and England, showed that pupils from indigenous and minority ethnic backgrounds recognized the importance of history as a school subject, but valued different types of history. For example, the Dutch pupils were asked to identify the five most important types of history they would like to study; minority ethnic pupils were more likely to rank the ‘history of my religion’ and the ‘history of where I was born’ higher than indigenous pupils who ranked national history highest. This raises fundamental questions about the content of the history curriculum in a pluralist society. The danger is that students from minority ethnic backgrounds, as shown in separate studies by Traille [20,21] and Epstein [1], find the history curriculum alienating, exclusive and/or does not match their own personal understanding of the past, so that ‘school’ history may be rejected as unimportant or inadequate.

2.2. The Challenge of Changing Trainee Teachers’ Ideas, Attitudes, Beliefs and Actions

The lack of cultural and ethnic diversity within a curriculum does appear to be related to the profile of the teaching population, which in the western world is predominantly white and middle class. As Gay [22] highlights, a curriculum is a social and cultural construct that reflects the ‘values, perspectives, and experiences of the dominant ethnic group’, whilst other groups are marginalized. Although there have been calls to diversify the teaching population, the majority of teachers are still likely to be drawn from the dominant cultural and ethnic groups, so there is a need to find ways to help them teach a more diverse curriculum. Unfortunately, the research evidence shows that trainee teachers and teachers from the dominant social group often find it difficult to embrace diversity within the curriculum they teach [23,24,25]. This seems related to their life experiences which have shaped their attitudes, values, beliefs and actions. This is not necessarily due to overt racism but a failure to acknowledge the privilege of ‘whiteness’ [26,27,28].

To bring about a change in such attitudes, values and beliefs and therefore to influence classroom practice, requires a shift in the way trainee teachers and teachers think. However this appears difficult to achieve. Successive literature reviews [29,30,31,32] examining attempts to develop awareness of and greater commitment towards cultural and ethnic diversity amongst trainee teachers, show a negligible impact. Different teacher training courses have provided school experience in multi-ethnic schools, have used reflective journals, self-analysis, including raising awareness of the privilege of ‘whiteness’, and so forth, yet the research provides little insight into teacher training practice that makes a major difference. Cochran-Smith et al. [29] claim that attempts to alter teachers’ attitudes and beliefs result in ‘modest or uneven effects depending on teachers’ backgrounds and quality of supervision and facilitation.’

In many ways these findings are unsurprising given what is known about the difficulties of changing the way trainee teachers think about teaching and the limited impact of interventions. Virta’s [33] study of Finnish trainee teachers shows their initial conceptions of teaching and how to teach emerge relatively unscathed from their training:

The nature of the problem is further outlined by Korthagen et al. [34]:

Teacher educators appear to be faced with an almost impossible task. Not only do student teachers show a strong resistance to attempts to change their existing preconceptions, but these preconceptions also serve as filters in making sense of theories and experiences in teacher education. The resistance to change is even greater because of the pressure that most student teachers feel to perform well in the classroom…In stressful conditions, people try even harder to keep their equilibrium…Thus teacher educators appear to be involved in the paradox of change: the pressure to change often prevents change.

However there appears to be an area that offers a means of bringing about change but which seems less well researched than other areas, and that is a focus on the purpose of teaching curricular topics. By purpose, I mean trainee teachers and teachers need to understand the rationale and/or possible range of rationales for teaching particular curriculum topics, and to understand how the rationale(s) actually informs curriculum choices. As Barton and Levstik [16] argue, ‘If we want to change teachers’ practices, we must change the purposes that guide those practices.’ Yet purpose is an often neglected part of a trainee teacher’s study, but would appear to be a valuable exercise [35], because change is more likely to occur in a teacher’s ideas and actions if they appreciate the need for change [34], and that change is more likely to occur where it is closely linked to a teacher’s sense of identity, which is often centered around their identity as a subject teacher [36].

Indeed, purpose is generally seen as an essential question in any issue related to curriculum. Tyler’s [37] classic discussion about the basic principles of curriculum identifies educational purposes as one of the fundamental questions to address. However, as Apple [38] explains, ‘Professional discourse about the curriculum has shifted from a focus on what we should teach to focus on how the curriculum should be organized, built and evaluated.’ Hopmann [39] and Priestley [40] show how, particularly in the Anglophone world, assessment systems have come to dominate educational systems, which is at the expense of more fundamental, yet crucial questions such as why should something be studied.

2.3. The Relationship between Purpose and Diversity in History

There is a need to focus on purpose in relation to teaching particular topics, because, as Haydn and Harris [41] have shown in the case of history in England, teachers are not always clear about the rationale for teaching particular topics. They often hold generic, abstract ideas about why the subject matters but they have seldom been required to match this to explicit areas of content. Barton and Levstik [16] argue that purpose is the major lever for improving the quality of history teaching:

If we hope to change the nature of history teaching, then we may have a greater impact by focusing on teachers’ purposes than on their pedagogical content knowledge.

Although many justifications for teaching history have been advanced, it is possible to argue that cultural and ethnic diversity is an integral part of these reasons. Barton and Levstik [16] have helpfully identified a number of ‘stances’, which provide different reasons for the study of history (although these are not exclusive categories and overlaps are possible). These are labeled ‘identification’, ‘analytical’, ‘moral response’ and ‘exhibition’ stances (the latter offers the least convincing rationale for studying history, focusing mainly on the acquisition of factual knowledge). By demonstrating that diversity is inherent in any of the rationales for studying the past it is hoped that trainee teachers would be more likely to embrace diversity.

The ‘identification’ stance is linked to a sense of identity, be that at a personal, community or national level, and history is a major factor in shaping our sense of identity [42]. Although there have been fierce debates about the teaching of national history in particular [2,43,44,45,46] there is a need to study history that reflects the realities of the past and the presence and roles of all groups—this would necessarily involve examining minority ethnic groups and different cultures.

The ‘analytical’ stance focuses on the role of analysis and how history helps people understand the present. This would logically require the study of topics related to contemporary issues, which will often relate to questions of diversity. This also implies studying a past that is familiar enough for us to make sense of the current situation. An alternative view argues that students also need to study the unfamiliar past [47]. This presents the opportunity to study diverse cultures, not because they have a direct relevance to issues today, but because they tell us something fundamental about the human condition. In studying both the familiar and unfamiliar past diversity issues are important.

The ‘moral response’ stance explores moral questions and values raised by a study of the past. Although the values base of an historical education is a notion some feel uncomfortable with [48,49], values cannot be avoided. For some history has a ‘humanizing’ effect [47], for others it is a source of democratic values and citizenship [16,50], and addresses issues such as stereotyping and promoting tolerance. The explicit promotion of values will include ideas of fairness and tolerance and so will involve a study of examples where this has been absent; these often include the treatment of minorities within a society.

Others adopt a different stance, arguing for the need to understand history as a discipline [47,51]. This would also require a diverse past being taught. A disciplinary approach requires students to understand how history is constructed, that there are competing views of the past, and the evidential base that is used to support particular views; this would entail students looking at different individuals and/or groups to see how they view the past, which would encompass the views of minority groups or ‘other’ cultures. There is a need for students to appreciate the complexity of the past, rather than be taught some bland, simple generalizations. This would also mean that students should be able to see the role of all individuals and groups in the past to the development of society, and thus means diversity should be an inherent element in any study of the past.

Thus when exploring the rationale for studying history, diversity has a place in each of these ‘stances’. Importantly, this allows teachers to hold different ideas about the point of studying history, but emphasizes that diversity is inherent in each position. This helps trainees see the value of teaching a more diverse curriculum so hopefully helping them see a need to accommodate such ideas in their practice; this can also sit within their existing beliefs, rather than threatening them, which would probably result in resistance.

3. Methodology

This section will outline the research approach adopted, which was action research, and will also explain some of the steps followed during the process. Writing about action research is a particularly difficult challenge as the process of research is iterative due to the interplay of action and theory, plus there is data collection and analysis at different stages of the action research cycle (and having several cycles of action research further complicates the process), making it difficult to neatly disentangle findings which emerged at different points in the process. Levin [52] suggests an approach to writing that reveals ‘gradual learning’ and as the focus on ‘purpose’ became more prominent during the action research process and in subsequent analysis, this needs to be reflected in the writing of this article. Therefore this section will proceed with a brief discussion of the nature of action research, to justify the adoption of this approach, which will necessarily outline how my interest in this area grew. It will then be followed by a brief explanation of the initial stage of action research, often called the reconnaissance stage, which served to identify more precisely the areas that needed to be investigated and the action plan that was implemented. This will reveal the ‘gradual learning’ that took place, albeit briefly. This is followed by a short explanation of the way interventions were built into the course, and which were designed to alter the way trainees thought about diversity and how they could incorporate it into their teaching. The section will then explain who was involved in the study and the ethical tensions this created. Once these have been explained the article will explore the findings solely related to the issue of ‘purpose’, which emerged during two cycles of research, and the impact this had on the trainees involved in this project.

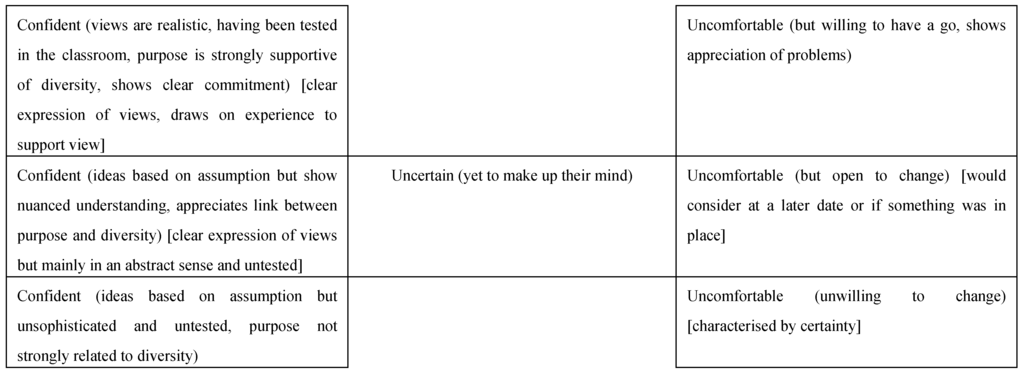

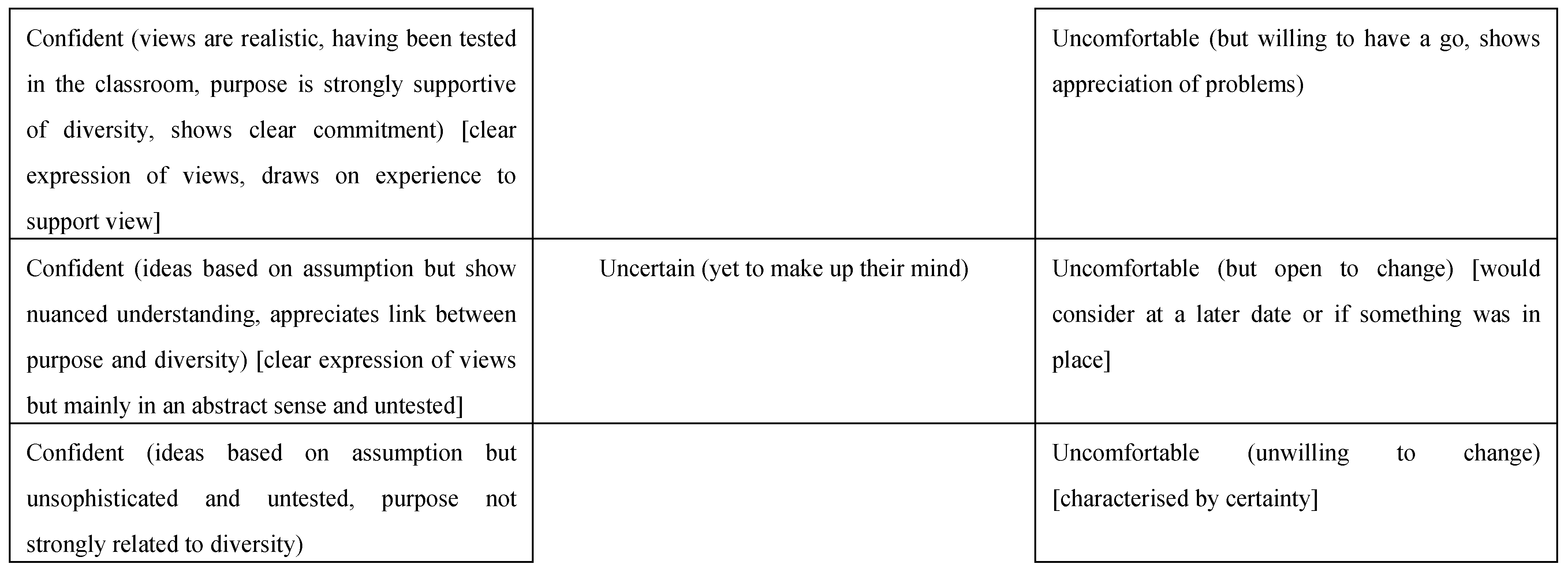

For the purposes of this article the findings will be drawn from interview data with the trainees who volunteered to participate in this study, as the interviews focused explicitly on the trainees’ developing understanding of diversity and the issues they encountered, and reveals much about the importance of purpose. Trainees were interviewed at the beginning of the academic year to establish initial starting points so that later changes in the trainees’ views could be identified, and so follow how the interventions shaped the way in which they thought about diversity and its place within the curriculum. A ‘confidence continuum’ (see Figure 1) was designed to help analyze the positions trainees adopted at different points in the course [53].

Figure 1.

The ‘confidence continuum’.

Figure 1.

The ‘confidence continuum’.

In 2007–8, seven trainees were interviewed at the start of the course and six at the end of the course (one trainee withdrew). In 2008–9 a further six trainees were interviewed three times (at the start, mid-point and end of the course); making a total of 31 interviews from 13 trainees.

The interviews lasted 40–60 minutes, were recorded with permission and transcribed in full. By using the same scenarios in each interview it was possible to track the trainees’ position across the year using the confidence continuum.

The interviews were based around scenarios that focused on an aspect of diversity and history (see Appendix), and the trainees had to discuss their views on the issue presented, for example whether, in a department meeting they would argue for the inclusion of a particular unit of work, along with their reasons and/or concerns. The use of these scenarios proved valuable and they elicited a range of responses from the participants, showing that they did not feel there were particular responses that were being sought.

3.1. Action Research

An action research approach was adopted as the focus was on improving my practice in order to influence the values, beliefs and actions of trainee history teachers, so that they would diversify the history curriculum they taught. Action research traditionally follows a cycle that starts with a reconnaissance stage to identify the issues that need to be addressed to improve a give situation, followed by an action plan to change the situation, which is implemented and monitored, and finally the impact of the intervention is evaluated. From here the cycle can be continued if required, or can move in a different direction. Reason and Bradbury [54] define action research as:

a participatory process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes. It seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern to people, and more generally the flourishing of individual persons and their communities.

Reflection on my own practice in training teachers using Critical Race Theory (CRT) [55,56,57] made me self-conscious of my own limited experience of diversity and raised concerns about my ability to support trainees’ understanding of this area. Exploring my biography I was able to appreciate the shortcomings of my personal experience and practice, due in part to my own background, which as a white middle-class teacher educator (and former high school teacher) had been essentially mono-cultural. I also used CRT to analyze my course materials on the ITE program and the history curriculum in general. It became clear that my course materials were essentially mono-ethnic and although the history curriculum in England has the potential to present a more diverse view of the past (see Qualifications and Curriculum Agency (QCA)) [7], in reality this is not being realized [58].

As a consequence I recognized a gap between my desire to develop my practice and insights into diversity, as well as a feeling of my inadequacies in being able to bridge this gap. Action research held out the prospect of enabling me to address these tensions as reflected in McNiff’s [59] notion of ‘I-theories’. At the same time the project would support the development of a particular set of values. These included a commitment to developing ideas of tolerance and mutual understanding through teaching an appropriate history curriculum as well as an awareness of the unintended consequences of what we may teach and its impact upon pupils from a variety of backgrounds. There was thus a social justice element to the study. As Somekh [60] explains, action research is not morally neutral and is recognized as a means of achieving social justice.

3.2. The Reconnaissance Stage

Having identified an area of concern, I needed to explore the issue more deeply so as to understand the nature of the problem. During the initial stages of the study, an approach to data analysis, drawing on principles of grounded theory [61,62] was adopted; open coding of interview transcripts from eight experienced teachers and five trainee teachers, followed by a process of exploring links and relationships between codes, identified a number of issues which were felt to be important in enabling trainee teachers to engage with diversity effectively [53,63]; these features included:

- greater awareness of the needs of pupils from minority ethnic backgrounds;

- greater awareness of ‘self’ (and the limitations of one’s own knowledge and experience);

- understanding appropriate pedagogical approaches to teaching diversity (to avoid insensitive handling of more diverse content);

- appropriate selection of curriculum content (to present a more diverse curriculum);

- and purpose (namely the reasons why subjects should be taught in the curriculum).

These issues (i.e. pupils, self, pedagogy, content and purpose) became the categories used to examine trainees’ interview transcripts. As the study progressed over a three year cycle, the issue of purpose seemed to be a useful means of unlocking trainee teachers’ willingness to engage with diversity, and given what is known about the challenge of bringing about change in how trainee teachers think and act, this seemed worth further analysis.

3.3. The Intervention

The year long ITE course in England requires trainee teachers to spend two thirds of their time in schools and one third in the university setting, and this intervention focused on what the course tutor could do within the university setting. To help trainees feel more comfortable and confident in embracing cultural and ethnic diversity in their practice, I had to do this within my own practice, and so I made a conscious decision to ‘infuse’ my course with more cultural and ethnic diversity [25,64]. This meant that the course materials I used to exemplify how to teach historical concepts and processes reflected a broader range of culturally and ethnically diverse topics. This was generally in the form of examples from another culture (e.g. the Islamic world), looking at the experiences of minority groups within society (e.g. the black and Asian experience in the UK) and looking at the interactions between societies/cultures (e.g. the British in India or the Arab Muslim world and the Christian West). These examples provided a constant ‘background’ of diversity. In addition there was a session focused purely on cultural and ethnic diversity and another on teaching sensitive and controversial topics in history (although I stressed that diversity should not be always be seen as sensitive and controversial). A focus on purpose was a recurring theme through the course. At the start of the course, trainees were set an assignment entitled ‘why should young people study the past and what should they therefore study?’ In subsequent sessions trainees were often asked to examine why particular topics should be taught (and how this would influence content selection and how it should be taught in order to match purpose to content and pedagogy), e.g. in a session on working with evidence, trainees were asked to examine why the Trans-Atlantic slave trade might be taught and therefore what materials should be selected and how they should be deployed.

3.4. The Sample and Ethical Considerations

All the teachers who agreed to be part of this study were aware of the nature of the study and gave written consent for their participation. All of them were white and the overwhelming majority came from mono-ethnic backgrounds in terms of their upbringing, education and work experiences (see Table 1; all names are pseudonyms). Thus trainees were encouraged to look beyond their own cultural and ethnic identities and context and examine the value and importance of creating a more inclusive curriculum; exemplar history teaching materials throughout the course drew upon a wide range of cultural and ethnic examples, trainees were required to broaden their subject knowledge of more diverse topics, and there was an explicit focus on the value of developing a more diverse curriculum.

Table 1.

Brief biographical information on trainee teachers who participated in the research.

| Trainee 2007–2008 | Gender | Age | Ethnicity | Degree and employment/school experience history |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharon | F | 27 | White British | 2:1 in Ancient History and Archaeology, 5 years’ work in financial services industry |

| Dominic | M | 23 | White British | 2:2 in History, worked in a Pupil Referral Unit |

| Jess | F | 21 | White British | 2:1 in History and Politics, voluntary experience as a student, taking younger pupils on camps |

| Louise * | F | 48 | White British | 2:1 in History, career in tax sector |

| Carol | F | 25 | White British | 2:1 in History, no school experience |

| James | M | 50 | White British | History degree from Princeton, career in financial sector, some experience as a cover supervisor |

| Anne | F | 23 | White British | 2:1 in History, worked as a Learning Support Assistant (LSA) in a secondary school |

| Trainee 2008–2009 | ||||

| Jane | F | 25 | White British | 2:1 in History and Politics, worked as a LSA in a secondary school, travel and teaching in Ghana |

| Kate | F | 21 | White British | 2:2 in History, work experience in secondary school settings |

| Jake | M | 24 | White British | 2:2 in Modern History, worked as a cover supervisor at a secondary school |

| Grace | F | 22 | White British | 2:1 in History and Drama, young leader for Brownies/Guides and work experience in a Pupil Referral Unit |

| Ally | F | 24 | White British | 2:2 in History and Education Studies, worked as a LSA in a secondary school |

| Emma | F | 21 | White British | 2:1 in History, worked as an activity leader on a youth camp |

* this trainee withdrew part way through the course.

As an ‘insider researcher’, investigating my own practice, there was a tension between my role as course tutor and researcher, for example, I may make negative judgments as a researcher about the ability of trainee teachers to incorporate diversity in their practice, but as a tutor I needed to be supportive and maintain the confidence of my trainees. Zeni [65] argues that action research should be characterized by open communication unless there is perceived risk. In this case the risk was my role as researcher would undermine my role as tutor; using the idea of the ‘ethics of caring’ [66,67] my role as tutor was the more important and so any negative analysis of the trainees’ views towards diversity were not shared. I was also conscious that as their tutor, the trainees may have provided responses they thought I would find ‘acceptable’. To counter this I used scenario based interviews. As Joram [68] explains:

The rationale underlying this methodology is that when commenting on a dilemma, participants’ beliefs and attitudes will be reflected in their responses, and the researcher can then cull the transcripts of their verbal responses to identify patterns. Thus, the methodology is designed to indirectly tap into participants’ beliefs…and attitudes.

4. Findings

Using the confidence continuum it was possible to place trainees according to their levels of confidence in understanding the purpose of teaching different topics. However it was clear that some trainees exhibited greater levels of confidence than others, so further analysis was carried out, based around the category of ‘purpose’. Using open coding [69], additional properties for this category were explored. This analysis identified three dimensions. There were those for whom an understanding of purpose reinforced existing ideas, those for whom purpose challenged their preconceptions and those for whom purpose was one of many competing demands on their energies.

Given the number of students involved and the richness of the data it is not possible to examine the views of all the students, so what follows is necessarily selective but the aim is to explore the range of views and positions that were expressed. The following sections contain six trainees, three from each cohort, with a trainee in each of the categories.

4.1. Purpose as Reinforcement of Ideas

Four trainees were identified in this category. These were students who had a clearly defined and attuned understanding of the value of diversity and why it needed to have a higher profile in the curriculum. The course did not therefore challenge the way these students thought but served to reinforce or mould their level of understanding.

Anne was a trainee on the course in 2007–2008. She showed a good understanding of diversity issues on her arrival. She thought it was misleading to talk about teaching British history because the history of different people and places is interconnected and therefore difficult to separate them out; she believed pupils should gain a more holistic, balanced view of the past. In addition she saw history as having a role in countering racism and stereotypes. By the end of the course, these ideas were still intact but Anne was able to identify the specific purpose behind particular topics and was therefore able to talk about what would be appropriate content and pedagogical approaches. For example she thought teaching about the British Empire would help to explain why Britain had such a multicultural population and could therefore help to prevent racism, whilst a unit on the ‘War on Terror’ would help to break down unhelpful stereotypes about Muslims; at the start of the course she had said she would not teach the ‘War on Terror’ as it was too controversial but now she could see a clear purpose and consequently could see how to approach teaching the topic and would want to teach it. Interestingly, Anne was unclear about the purpose of other topics, thus she could not understand the point of teaching the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. This was a reaction to what she saw as inappropriate content in her second placement school, and when asked why the topic was taught she simply replied ‘I’m not sure’. Overall she seemed much more convinced of the need to address diversity; when discussing a session about the challenges of addressing diversity and the reasons for examining diversity in the curriculum, Anne said:

…the fact that there is even an issue means that something needs to be addressed and I think that is probably why I’m a lot more now, like something needs to be done and I think if people don’t because they’re worried that they’re going to upset someone, it’s just going to get worse.

Even though Anne was placed in two predominantly white schools, the course had helped to affirm Anne’s original positive disposition and understanding of diversity issues. This had also remained intact despite a particularly traumatic placement (due to problems with in-school support she was moved to another school where she was able to complete the course successfully).

Jane joined the course in 2008–2009 and was unusual amongst the trainees in having a strong sense of commitment to diversity issues from the outset of the course. This was mainly due to her degree studies which had included large elements looking at imperialism and colonialism, plus some time travelling and teaching in West Africa. Jane had clearly developed ideas as to purpose of teaching a diverse curriculum. To her a key purpose was the need to address ignorance: ‘I think a lot of racism and religious animosity comes, stems from fear, stems from lack of understanding which creates fear.’ A focus on diversity in history would help to address stereotypes and help students understand how and why the world is as it is today. By the midpoint of the course she was still very clear on why diversity mattered and therefore was clear as to why certain topics should be studied, However she was also increasingly aware of the complexity of the issues, for example she was uncomfortable with the idea that she may be promoting a particular moral position through her teaching, and she was not sure whether this was her role as a teacher. She was also acutely aware of the difficulties she faced in trying to bring diversity into her practice, thus the host school acted as an obstacle; Jane did diversify her host school’s curriculum but was afraid that it would appear tokenistic given the constraints she faced.

The university based part of the course had provided much encouragement and support for her ideas; she recognized that the ‘infused’ nature of the course had been helpful. But she was worried about the future when she would be working full time in schools; as Jane expressed it: ‘I am worried that it will all slip away when you’re institutionalized.’ She was clearly aware of the dangers of having to fit into a history department and the potential ‘wash out’ effect that could have, which raises questions about support beyond the end of the initial training period. By the end of the course she was very confident about teaching a more diverse history curriculum. Her second host school had given her a great deal of freedom and support, so she had developed very sophisticated insights and understandings about the need to teach a diverse curriculum and how this could be achieved in practice. Her only concern remained the question about the future and the extent to which she would be able to implement her ideas. It was clear she saw a need to fit into whatever school she worked in, plus she felt she lacked status as a young, newly qualified teacher. Jane saw the need for leadership and commitment from elsewhere:

Until teachers see it as a real priority which has got to come from higher up…it’s got to come from senior leadership in the school and the government, because, I mean, one teacher I spoke to said, oh, you know it’s just another, um, what was the word he used, you know, it’s just another phase, it’s just another initiative that’s going to go and die a death.

Although Jane was firmly committed to addressing diversity in the curriculum she felt she would not be able to influence anything until she herself had achieved some level of responsibility for developing the history curriculum (e.g. as a head of department). She was concerned that by then her ideas may have been weakened.

Jane’s level of commitment to diversity was in part due to the clear sense of purpose she saw in ensuring she taught a diverse curriculum. The course strengthened this belief, and she was able to build on this and develop her confidence in developing her pedagogy, subject knowledge and understanding the needs of pupils. Since leaving the course, I know through continued contact with her that her concerns about not being able to implement her ideas had proved without foundation, and she has been given responsibility for developing this facet of the history curriculum within her school.

4.2. Purpose as Challenge to Preconceptions

This category embraced the majority of students, with five trainees in this category. Trainees either had never seriously had to consider diversity issues before this point or held inappropriate or naïve ideas; for example trainees did not recognize how they might inadvertently create or reinforce stereotypes through content selection or felt such topics could be bolted onto the end of a course once other mainstream topics had been taught. The emphasis on diversity in the course served to challenge and to shape their thinking strongly, although in some cases their commitment to diversity was fragile.

Carol, who joined the course in 2007, was typical of many trainees who admitted that they had never considered diversity was an issue they would have to consider on a teacher training course. Not surprisingly her interview at the start of the course revealed a lack of clarity or sophisticated thought about diversity and the reasons why it should be a consideration when deciding what historical content to teach; for example she said she would welcome the chance to teach more diverse topics because they sounded interesting rather than appreciating the value of teaching such topics to students. Instead she spoke more confidently about potential pedagogical approaches she could try when teaching different topics. By the end of the course there was a greater level of sophistication and depth to her thinking; thus she argued that history should not be parceled up into ‘national’ history, ‘black’ history and so forth, but should be seen in a more holistic and complex way. Although she had become more certain and confident in her views, at the same time it was evident that she had also become much more uncertain in other ways. Indeed, when discussing whether a traditional British history program was appropriate, she was more assured in her view that it ought to be ‘more mixed’. She noted that what was taught was essentially English history rather than British, and although she believed that most pupils did not really take much notice of what history they were taught, she felt there was a need to diversify the curriculum. Her views were based upon her school experience; as both her placements had been in predominantly white mono-cultural settings she was able to observe the limitations of teaching a traditional curriculum, but had not had the experience of teaching a more diverse one. Her views were shaped by her experience on the course and serious self-reflection; as she explained in relation to national history:

I think it should be definitely more mixed. There’s no reason why it just has to be British history. I was doing some reading about it and talking about its culture, it’s not a nation anymore, we can’t just define it as one nation.

Carol was also certain that she would teach topics like the slave trade and be happy to do so, although she was aware that her opportunities to teach such topics, and therefore her experience, was limited. However, apart from the reasons for teaching about the ‘War on Terror’, her views showed a limited understanding of the purpose of teaching different topics, and she struggled to articulate her ideas; when asked why the Transatlantic Slave Trade ought to be taught she replied:

Um, I don’t know. [pause]. I suppose, links to the Empire to, er, the country did bad things, it happened…um, I don’t know what I’d want, I don’t know really.

Carol was still more confident talking about pedagogical approaches, although again she stressed she had not had the experience of doing this so was unsure how successful her ideas would be. Similarly her lack of experience meant she had had few opportunities to teach pupils from minority ethnic backgrounds and so she was unsure how this would affect the way she taught.

What was evident throughout the interview was Carol’s clear understanding of her current stage of development. She described herself as ‘naively confident’. She was prepared to tackle diversity in the curriculum, but was aware that she still had to gain a deeper understanding of a number of issues, in particular the rationale for teaching specific topics. Overall, Carol was firmly placed within the uncertain category on the ‘confidence continuum’, yet in many ways this was an improvement on her initial starting point. The experience of addressing diversity issues on the course had made her ask profound questions of herself and of the nature of the curriculum, but which were as yet unresolved. She was however concerned about how she would be able to follow these ideas into her first year as a teacher:

what I think will be a problem for me in the first year of teaching is that you’ll just get through the lesson, just to get through the lesson and it’s not for another year or so when you can really reflect on the actual lessons and what your aim, really aims are in the lesson and have you, are you actually achieving them.

So although, Carol had developed considerably during the year, doubts remained as to the extent to which ideas about teaching a more diverse curriculum were firmly embedded.

Emma was a trainee on the course in 2008–2009, and like Carol admitted that she had never considered diversity issues prior to the start of the course. She had been brought up in a rural monocultural area, her education had been in essentially all-white settings and so in many respects her lack of prior experience with diversity was similar to many of the other trainees. During her first interview she was very unsure about the purpose for studying a range of the topics discussed; for example when asked what the point of studying the British Empire was, she answered ‘I don’t actually know to be honest.’ Her views on some topics were slightly more convincing, for example she saw that a study of British history could help develop a sense of identity although she was aware that ‘Britishness’ was a very loose term in relation to identity formation. By the time of the second interview, Emma spoke more about the type of content she would introduce into the curriculum but did not elaborate as to the purpose, apart from an explanation that British history was inextricably linked to other parts of the world and so appreciated that British history was diverse and therefore the topics chosen should reflect this. It was evident in her interviews that she was grappling with the issues raised by diversity and acknowledged that the ‘infusion’ of diversity throughout the course was responsible for this. By the end of the course however she had come to realize the importance of purpose and was increasingly able to identify this within the topics she had taught:

I know it’s towards the end that I started to get it... I can see it through the Holocaust and I think almost doing that topic has made me realize with other topics what their purposes are and it’s almost like the penny’s dropped and I look at things slightly differently to how I did before.

This proved pivotal in helping her understand not just why certain topics ought to be taught, but it allowed her to see how she could approach teaching them; for example in the interview she explained how she had struggled to see the point in teaching a unit on the Indigenous Peoples of North America, but once she had made her breakthrough she could explain how she would approach this unit much more effectively. She had also come to realize the weaknesses in the school’s approach to planning, which focused much more on what to teach and how to squeeze it into the curriculum rather than considering what they wanted to achieve and therefore what should be taught. As Emma said ‘the purpose should be what’s driving the lessons and your choices.’ Although Emma recognized the progress that she had made, she was also conscious that moving into a full time post might make it difficult for her to develop her thinking and practice further, partly due to the new demands this would place on her, but also because her new department may not see diversity as a priority.

4.3. Purpose as One of Many Competing Demands

This category encompassed three trainees who made little headway in their thinking or understanding, even if they had been positively disposed to the issue of diversity from the outset. What set this group apart from the others were the difficulties they encountered during the course which served to disrupt their progress and so they never same to see diversity as a priority or a means of addressing the concerns that they encountered.

James was on the course in 2007–2008 and was a mature student who had a huge passion for his subject. He was aware that he had much to learn to be an effective teacher and that this would include understanding how to engage students of all ages and backgrounds. As such he was perfectly aware that students from minority ethnic backgrounds may find some history topics more engaging than others purely because of their sense of identity. Thus he felt very positive about topics such as the British Empire, which he felt would be engaging to a wide range of pupils. However he was very concerned about his level of subject knowledge and was cautious of teaching anything that addressed racism—he was afraid that pupils might use this as an excuse to disrupt the lesson or accuse him of being racist. He saw history could help to address stereotypes, but his choice of stereotypes that could be addressed was interesting; in both interviews he referred to a black historian who had investigated the effect of the slave trade on West Africa and reportedly found many West Africans who felt the area had benefitted from the trade, and therefore focused on disrupting ‘black’ perceptions of the slave trade. By the end of the course his ideas had not changed. He seldom spoke about purpose when discussing any of the topics and when asked about teaching the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, although he could identify the issue of stereotyping as above, he said:

But I don’t know what the purpose, I’ve never taught this or come across it, so I wouldn’t actually know what the purpose is of teaching that, I’d have to think about it.

However his position is understandable when put into context. James struggled throughout much of the course, both in terms of planning lessons that were appropriate and therefore having to address the ensuing behavioral problems. As he said: ‘I’m just looking every day as it comes’ and ‘I try just to survive tomorrow’. For him, addressing the question of purpose was not paramount because he could not see how it would help him to address the very real issues he faced in his teaching, although in reality it may well have helped considerably.

Jake was on the 2008–2009 course and like James realized diversity would be an issue he would have to explore. He could see the value of making the curriculum more diverse and spoke confidently about his ideas during the initial interview, about the point of addressing diversity in a general sense; thus he saw the history curriculum as a means of countering discrimination, raising issues of identity and encouraging tolerance. However, he was unable to give specific reasons why particular topics should be taught. In the interview at the midpoint in the course, Jake’s understanding of the purpose of different topics had developed unevenly. He could see that topics such as the Trans-Atlantic slave trade had a role to play in addressing stereotypes and demonstrating that Britain’s past was more diverse than is often portrayed. However many of his ideas were still inchoate; when talking about the purpose of teaching the history of the British Empire he merely said ‘it’s an important topic’ but when asked for further explanation was unable to offer anything else. By the end of the course his ideas were still relatively undeveloped. He still saw the value of diversity generally but he continued to struggle to articulate why certain topics ought to be taught. It seemed that he had stalled in his development, and probably is a reflection on the difficulties he encountered during his final teaching placement. His mentor had become increasingly frustrated at the limited range of pedagogical strategies Jake used and pupils had become increasingly restless and bored with his approach. Consequently he became very focused on simply ‘getting through’.

In this scenario the importance of the context of learning becomes particularly acute. To an extent all trainees encountered difficulties trying to include diversity into the curriculum that they taught. A socio-cultural analysis of the process of learning to teach helps to explain the difficulties. Many of the trainees spoke of the ‘busyness’ of the course and the difficulty of finding time to think about how to address this issue plus a lack of time to reflect. There were also concerns expressed about how the extent to which diversity was a priority, either for themselves or for the host departments in which they were working. On top of this was the issue of personal disposition and the extent to which trainees were willing to take any opportunities to bring diversity into the curriculum that arose or whether they made opportunities for to teach a more diverse curriculum.

5. Discussion

A focus on purpose does appear to impact on the ability of at least some trainee history teachers to engage with cultural and ethnic diversity within the curriculum. Although the impact is not uniform, an analysis of the data shows that there are important issues which warrant further attention. In particular the need to engage with fundamental questions about curriculum, the role of subject specific courses where diversity permeates the program, the learning context within which trainee teachers operate and what happens to trainees once they move into full time employment emerge as areas for further reflection; and each of these are discussed in turn below.

5.1. The Need to Engage With Fundamental Questions About the Curriculum

The focus on the purposes of the subject and its relationship to diversity does appear to have some positive effect on the majority of students, even if it only serves to create uncertainty, as this shows that trainee teachers are grappling with the ideas raised. Although the impact of a focus on purpose is uneven, the value of understanding why a topic should be taught was regarded as valuable by the majority of trainees, and did provide important leverage to support most trainees in thinking differently about what should be taught and why. It is acknowledged that it is difficult to change teachers’ beliefs [34,70], but a focus on something like the rationale behind a subject, where the subject is closely aligned to a teacher’s sense of identity [36], does seem to offer a means of exerting change. For example, Jane needed little support in understanding the connection between the purposes of history teaching and diversity, but the course served to reinforce these existing ideas and gave her the confidence and relevant knowledge to implement her ideas in practice. Emma became far more aware of the importance of establishing the point of teaching something, and was therefore able to develop her appreciation of the place of diversity within history. Once this was clear then she could consider the appropriateness of content and preferred teaching approaches, although her subject knowledge still needed further development.

Although not all trainees were able to respond to the issues such deliberation generated, it does appear to be a significant lever in developing the thinking of the majority of trainees involved in this study, and as such would benefit from further research. On its own, a focus on purpose is not enough to change the way trainees thought and acted, hence the need to provide support in areas such as subject knowledge development and examining appropriate pedagogy, but it did provide a suitable stimulus to force trainees to question their existing ideas, attitudes and beliefs.

5.2. The Need for Subject Specific Courses Infused With Diversity

The research literature [29,30,31,32] highlights the problem of getting white trainee teachers, with limited experience of diversity issues, to engage seriously with this field. The literature on multicultural education and initial teacher education [25,64] claims that courses ‘infused’ with diversity, particularly subject specific courses, are more likely to be effective than courses where it is an additional or optional course. This research shows that many white trainees from mono-cultural backgrounds are able to appreciate the need to address diversity, given suitable stimulus, and many are willing to engage with issues, and will look, albeit with varying degrees of commitment, for ways to address this within the curriculum. However, I would argue that as part of this ‘infusion’ approach, trainee teachers need to address the notion of purpose, i.e. why their subject should be taught and the relationship of these reasons to diversity.

While the results from this study show that trainees reacted in different ways to the questions of purpose and diversity, it is possible to identify some trends and ideas that would benefit from further research. Trainees who entered the course with well-developed ideas found the reinforcement from the course helpful. For most trainees the course was important in making them explore these issues (often for the first time) and helping them to appreciate their significance. Although this latter group had a better understanding of the complexity of diversity issues, they still needed further development as they moved into full time employment.

5.3. The Learning Context within Which Trainee Teachers Operate

Some trainees, even those who were keen to develop their understanding of diversity, made little headway in teaching a more diverse curriculum. For trainees who are having a ‘tough’ time in school, paying attention to diversity can become less of a priority, as they simply strive to survive. A way forward seems to be to work closely with the trainees and school based mentors to explore the basis of the problems the trainee is encountering, which in many cases is to do with fundamental issues such as what they are teaching and why; there is a need for teachers to engage with these fundamental questions about purpose in history [71,72]. Students often fail to see the point of what they are studying in history [73,74], and this can be associated with teachers’ own lack of understanding or failure to communicate this to students [75]. This emphasizes the point that the source of many difficulties in education is the curriculum; for pupils the curriculum may appear irrelevant, inappropriate or inadequate [9,15,22], but it also raises difficulties for teachers if they do not understand its purpose either. Once this is clear trainees often find it easier to plan and teach lessons with confidence, or can focus on other aspects of their practice secure in the knowledge of what they are trying to achieve. In this sense, discussions about the purpose of teaching a diverse curriculum can help all trainees, regardless of subject or age range being taught, understand more generally the point of teaching topics that better reflect the nature of society, rather simply topics relating to the dominant social group.

5.4. The Move into Full Time Employment

A major concern that emerged strongly was the question of continued support for trainees once they finish the course. For example, Carol was reflecting very seriously on the issues raised by the end of the course, but finished the course with these unresolved and so there is the potential for these to remain unresolved without further support and challenge. Even where trainees had reached a point where they were confident about putting their ideas in to practice, there were serious concerns about their ability and opportunity to do so. This seems to be very closely associated with their perceived status as new and inexperienced teachers; even Jane, who was the strongest advocate of diversity, said:

in terms of teaching in the next few years, then I’ve got to sort of do what the school wants me to do, so, um, that would stop me from doing anything major but I don’t suppose, it wouldn’t stop me from drip feeding diversity into the traditional, British curriculum…I think a lot of us have said, actually, it would be really good if, like a lot of elements of the course we can come back and do when we get made head of departments, how a lot of the things are actually things that we almost can’t use until we’re at that position by which time they’ve been forgotten and been sucked into system.

In one sense this represents a ‘chicken and egg’ situation—trainees will feel greater encouragement to address diversity in the curriculum where schools address diversity seriously, but schools are unlikely to do this until sufficient teachers come through training willing to address diversity seriously. This is where the role of partnership in teacher training can offer solutions, but in turn this requires those in teacher training to have the insights needed to provide such support [76]. Since the start of the project more of the schools with which I work have expressed an interest and desire to interweave diversity into their practice, which in turn should support future trainees.

6. Final Thoughts

As Cabello and Burstein [70] stress, ‘teachers replace beliefs only if they are challenged and appear unsatisfactory. Even then…they change beliefs only as a last alternative.’ This highlights the challenges of getting trainees to address issues such as diversity, particularly if they lack personal experience. It is important to find ways which connect with teachers’ beliefs, attitudes and values in order to exert change. This is why a focus on purpose appears to offer a productive line of enquiry; by working from a teacher’s sense of purpose, linking this to diversity and showing how they are compatible is more likely to induce change than adopting a confrontational approach, which is more likely to result in resistance. It seems to promote what Korthagen et al. [34] see as one of the key factors in bringing about change in teachers’ conceptions and actions, namely for teachers to appreciate an internal need for change. What appears to be lacking in many diversity courses is the focus on the imperative for change, i.e. trainee teachers do not see an internal need to change themselves.

Although this study shows that this is not an easy goal in itself, the findings suggest that there is sufficient change in the understanding and practice of many trainees to warrant further attention on the idea of purpose, which requires trainee teachers to engage with fundamental questions about the purpose of education, and the purpose of teaching particular subjects and therefore the purpose of specific topics within the curriculum. The findings from this study suggest that a focus on purpose is a promising line of further enquiry, both for practitioners and researchers.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Epstein, T. Interpreting National History; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grever, M.; Stuurman, S. Beyond the Canon: History for the Twenty First Century; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, T. Howard’s end: A narrative memoir of political contrivance, neoconservative ideology and the Australian history curriculum. Curric. J. 2009, 20, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.; Guyver, R. History Wars and the Classroom—Global Perspectives; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gaine, C. We’re All White, Thanks; Trentham Books: Stoke on Trent, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Maylor, U.; Read, B.; Mendick, H.; Ross, A.; Rollock, N. Diversity and Citizenship in the Curriculum: Research Review; DfES: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Qualifications and Curriculum Authority. History Programme of Study for Key Stage 3 and Attainment Target; QCA: London, UK, 2007. Available online: http://media.education.gov.uk/assets/files/pdf/h/history%202007%20programme%20of%20study%20for%20key%20stage%203.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2011).

- Gillborn, D.; Mirza, H. Educational Inequality: Mapping Race, Class and Gender; Oftsed: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, S. Critical Multicultural Education and Students’ Perspectives. In The RoutledgeFalmer Reader in Multicultural Education; Ladson-Billings, G., Gillborn, D., Eds.; RoutledgeFalmer: London, UK, 2004; pp. 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Ten Steps to Equity in Education; policy brief; OECD: Paris, France, 2008. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/21/45/39989494.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2011).

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate. In Achievement of Black Caribbean Pupils: Good Practice in Secondary Schools; Oftsed: London, UK, 2002.

- Zec, P. Dealing with Racist Incidents in School. In Education for Cultural Diversity: The Challenge for a New Era; Fyfe, A., Figueroa, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.A. Approaches to Multicultural Curriculum Reform. In Race, Culture and Education: The Selected Works of James A. Banks; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.I. Comprehensive Multicultural Education: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gundara, J.S. Intercultural Education and Inclusion; Paul Chapman Publishing: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, K.; Levstik, L. Teaching History for the Common Good; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.A. Multiethnic Education: Theory and Practice; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education and Skills. In Ethnicity and Education: The Evidence on Minority Ethnic Pupils Aged 5–16; DfES: London, UK, 2006.

- Grever, M.; Haydn, T.; Ribbens, K. Identity and school history: the perspectives of young people from the Netherlands and England. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2008, 56, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traille, E.K.A. School History and Perspectives on the Past: A Study of Students of African Caribbean Descent and Their Mothers. PhD Thesis, Institute of Education, University of London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Traille, E.K.A. ‘You should be proud about your history. They made me feel ashamed’: Teaching history hurts. Teach. Hist. 2007, 127, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. Curriculum Theory and Multicultural Education. In Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, 2nd; Banks, J.A., McGee Banks, C.A., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, USA, 2004; pp. 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Causey, V.; Thomas, C.; Armento, B. Cultural diversity is basically a foreign term to me: The challenges of diversity for preservice teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2000, 16, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockrell, K.S.; Plaicer, P.L.; Cockrell, D.H.; Middleton, J.N. Coming to terms with “diversity” and “multiculturalism” in teacher education: Learning about our students, changing our practice. Teach. Teach.Educ. 1999, 15, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, H. Stability and change in U.S. prospective teachers’ beliefs and decisions about diversity and learning to teach. Teach. Teach.Educ. 2005, 21, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, E.; McAuley, A. Teaching for diversity by troubling whiteness: Strategies for classrooms in isolated white communities. Race Ethn. Educ. 2008, 11, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, S. You Wouldn’t Understand: White Teachers in Multiethnic Classrooms; Trentham Books: Stoke on Trent, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, J.L. Silence in the classroom/whispers in the halls: Autoethnography as pedagogy in White pre-service teacher education. Race Ethn. Educ. 2007, 10, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Davis, D.; Fries, K. Multicultural Teacher Education: Research Practice and Policy. In Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, 2nd; Banks, J.A., McGee Banks, C.A., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 931–978. [Google Scholar]

- Hollins, E.R.; Guzman, M.T. Research on Preparing Teachers for Diverse Populations. In Studying Teacher Education: The Report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education; Cochran-Smith, M., Zeichner, K.M., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Washington, DC, USA and AERA: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeter, C.E. Preparing teachers for culturally diverse schools: Research and the overwhelming presence of whiteness. J. Teach. Educ. 2001, 52, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, K.M.; Hoeft, K. Teacher Socialization for Cultural Diversity. In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, 2nd; Sikula, J., Ed.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Virta, A. Becoming a history teacher: Observations on the beliefs and growth of student teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2002, 18, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F.A.J.; Kessels, J.; Koster, B.; Lagerwerf, B.; Wubbels, T. Linking Theory and Practice: The Pedagogy of Realistic Teacher Education; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J. Exploring diversity through ethos in initial teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 1729–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Elliot, B.; Kington, A. Reform, standards and teacher identity: Challenges of sustaining commitment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, R. Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Apple, M.W. Is There a Curriculum Voice to Reclaim? In The Curriculum Studies Reader; Flinders, D.J., Thornton, S.J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 342–349. [Google Scholar]

- Hopmann, S. Restrained teaching: The common core of Didaktik. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 6, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M. Global discourses and national reconstruction: The impact of globalization on curriculum policy. Curric. J. 2002, 13, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydn, T.; Harris, R. Pupil and teacher perspectives on motivation and engagement in high school history: A U.K. view. Presented at the American Educational Research Association, New York, NY, USA, March 2008.

- Marwick, A. The Nature of History, 3rd ed; Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Husbands, C.; Kitson, A.; Pendry, A. Understanding History Teaching; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ismailova, K. Curriculum reform in post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan: Indigenization of the history curriculum. Curric. J. 2004, 15, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, K. Teaching history in schools: A Canadian debate. J. Curric. Stud. 2003, 35, 585–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R. History Teaching, Nationhood and the State: A Study in Educational Politics; Cassell: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wineburg, S. Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kinloch, N. The Holocaust—Moral or historical question? Teach. Hist. 1998, 93, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kinloch, N. Parallel catastrophes? Uniqueness, redemption and the Shoah. Teach. Hist. 2001, 104, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tosh, J. Why History Matters; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wineburg, S. Unnatural and essential: The nature of historical thinking. Teach. Hist. 2007, 129, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, M. The Praxis of Educating Action Researchers. In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, 2nd; Reason, P., Bradbury, H., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R.; Clarke, G. Embracing diversity in the history curriculum: A study of the challenges facing trainee teachers. Cam. J. Educ. 2011, 41, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. The SAGE Handbook of Action Reseach: Participative Inquiry and Practice, 2nd ed; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gillborn, D. Racism and Education: Coincidence or Conspiracy? Routledge: London, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. New Directions in Multicultural Education: Complexities, Boundaries and Critical Race Theory. In Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, 2nd; Banks, J.A., McGee Banks, C.A., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, USA, 2004; pp. 50–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Just What Is Critical Race Theory and What Is It Doing in a Nice Field Like Education? In The RoutledgeFalmer Reader in Multicultural Education; Ladson-Billings, G., Gillborn, D., Eds.; RoutledgeFalmer: London, UK, 2004; pp. 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Office for Standards in Education. Children’s Services and Skills History for all—History in English schools, 2007/10. 2011. Available online: http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/Ofsted-home/Publications-and-research/Browse-all-by/Documents-by-type/Thematic-reports/History-for-all (accessed on 22 September 2011).

- McNiff, J. Action Research: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed; RoutledgeFalmer: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Somekh, B. Action Research; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine de Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R. An Action Research Project to Promote the Teaching of Culturally and Ethnically Diverse History on a Secondary PGCE History Course. PhD Thesis, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, O.; Lopez, R. Teachers’ initial training in cultural diversity in Spain: Attitudes and pedagogical strategies. Intercult. Educ. 2005, 16, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeni, J. Ethics and the ‘Personal’ in Action Research. In The Sage Handbook of Educational Action Research; Noffke, S., Somekh, B., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 254–266. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, P.; Costley, C. An ethics of community and care for practitioner researchers. Int. J. Res. Meth. Educ. 2006, 29, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, G.B.; Rallis, S.F. Everyday ethics: Reflections on practice. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2010, 23, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joram, E. Clashing epistemologies: Aspiring teachers’, practicing teachers’, and professors’ beliefs about knowledge and research in education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2007, 23, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. Real World Research, 2nd ed; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, B.; Burstein, N.D. Examining teachers’ beliefs about teaching in culturally diverse classrooms. J. Teach. Educ. 1995, 46, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Slater, J.; Walsh, P.; White, J. The Aims of School History: The National Curriculum and Beyond; Tufnell Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, R. Reflective Teaching of History; Continuum: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Adey, K.; Biddulph, M. The influence of pupil perceptions on subject choice at 14+ in geography and history. Educ. Stud. 2001, 27, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydn, T.; Harris, R. Pupil perspectives on the purposes and benefits of studying history in high school: A view from the UK. J. Curric. Stud. 2010, 42, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydn, T.; Harris, R. Factors Influencing Pupil Take-Up of History Post Key Stage 3: A Report for the QCA; QCA: London, UK, 2007. Available online: http://www.uea.ac.uk/ ~m242/historypgce/qca3report.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2011).

- Maylor, U. Notions of diversity, British identities and citizenship belonging. Race, Ethn. Educ. 2010, 13, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Appendix

‘Scenarios’ used for interviews

- a) The National Curriculum includes a large amount of British history from 1066 to C20th, covering political, religious, social and economic developments. You are teaching in a school that has a mixed ethnic population and includes a diversity of religions. In this context how appropriate do you think it is for young people to learn about the political development of Britain and events such as the Norman Conquest, the Reformation, the development of Parliament and so forth? How comfortable would you feel about teaching such topics? If you were teaching in a predominantly white, monocultural setting, how appropriate do you feel this type of history would be?

- b) You are teaching the British Empire—you could focus on areas such as why it grew, the benefits of the empire, the perceptions of those ruled by the British, the downside of British rule, the contribution of the colonies to the British Empire and so forth. What ‘story’ would you want pupils to understand? What would influence your decision in deciding which angle to adopt? What concerns would you have teaching this topic? Would the nature of the school population alter how you would approach this topic? How comfortable would you be teaching this topic?

- c) You are teaching about the Transatlantic slave trade. What would you want to cover when teaching this topic and why? What concerns would you have teaching this topic? Would the nature of the school population alter how you would approach this topic? How comfortable would you be teaching this topic?

- d) Your department is discussing whether to include a GCSE unit on the ‘War on Terror’ as part of the coursework. This will involve looking at Afghanistan, the war in Iraq, 9/11 and so forth. The school has a large number of Muslim students. Would you argue for or against introducing this unit? Why would you adopt this stance? Would it alter your view if the school population did not include any Muslim students? How comfortable would you be teaching this topic?

- e) Your department, in a white, monocultural school, is discussing whether to include more multicultural topics within the curriculum, either more units on other cultures beyond Europe or the experience of ethnic minorities within Britain—currently 70% of curriculum time deals with ‘traditional’ British topics. This will involve doing less ‘traditional’ British history due to time constraints. Do you argue for doing more multicultural history, if so why and what multicultural topics would you include, or do you argue for the importance of keeping British history. How comfortable would you be teaching these topics?

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).