Abstract

Civic and citizenship education is a component of the school curriculum in all nation states. The form it takes, its purposes and the way in which it is implemented differs from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The pressures of globalization in recent times have meant that citizenship has increasingly come to be seen in global terms brought about by processes such as transnational migration, the homogenization of cultural practices and the development of supranational groupings that often seem to challenge more local versions of citizenship. Despite these pressures, the key responsibility for citizenship continues to rest with nation states. This paper will review issues relating to a more globalized citizenship and outline the strategies that nation states might adopt to ensure they remain capable of creating an active and engaged citizenship.

1. Introduction

In 1999, the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) conducted the second international assessment of civic education “responding to the expressed need of many countries for empirical data as they began to rethink their civic education programs in the early 1990s transitions” [1]. This IEA Civic Education Study involved 28 countries and 90,000 students. A decade later, the IEA conducted the third international assessment of civic education, this time involving 38 countries and 120,000 students [2]. The rationale of this study was not the transitions that had characterized the post-cold War world in the 1990s but rather the uncertainties and calamites that followed the destruction of the World Trade Centre in New York on 11 September 2001 and the related terrorist activities in places such as Bali, London and Madrid that followed in quick succession after 2001. Thus the last decade of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty first century witnessed global events that placed a spotlight on civic and citizenship education and its role in a changing world. It is important to understand these changing contexts.

One pervasive change that has been identified is related to global economic integration and in particular the growth and influence of technology in the global economy. Often referred to as “globalization”, this increasing integration has highlighted the interdependence of the world economy and the extent to which technology has enhanced this interdependence. For example, individuals across the globe continue to be located in a common geographic space such as China or Germany or the United States of America. Yet increasingly what happens in one society influences what happens in another. The manufacture of clothes in China impacts on prices and work opportunities for citizens in the United States, the financial crisis of 2008 could not be contained in a single geographic space and prices for drugs determined in Western nations impact on access to these drugs by people in developing countries. Yet globalization is not only economic in nature. Local cultures can also be challenged by technology enhanced processes that lead to more globalized music, fashion and food. These in turn may have economic impacts on local societies. As Mok [3] has pointed out “no matter how we assess the impact of globalization, it is undeniable that contemporary societies are not entirely immune from the prominent global forces”.

While the forces of globalization have been unmistakable across the international landscape, there have also been forces that have highlighted the continuing and significant role of individual nations. Kennedy [4] pointed to three broad elements that account for the continuing strength of nation states—the existence of states with strong governance structures, the increasing emphasis on national security in the light of 9/11 and the responses to the 2008 financial crisis that witnessed considerable intervention on the part of national governments. He has referred to these phenomena as a kind of “neo-statism” signaling the ongoing role of nation states even in an increasingly globalized world. As Keating [5] commented, “the nation-state model continues to have a grip on the intellectual imagination and its normative elements survive in much writing about politics”. The reason for this is not so much a romantic attachment to the nation state. Rather, it is because the everyday lives of citizens continue to be influenced by the decisions of national government whether they are concerned with new financial regulations, new state security arrangements or the variety of laws that cover such areas as transport, housing and education.

Kennedy [4] has also pointed to the influence of non-state actors on the international landscape and the need for civic and citizenship education to take account of these. Such actors have been responsible for the ongoing terrorism that has characterized much of the 21st century. The most well known is perhaps Al Qaeda but there are many more smaller groups and sometimes individuals who take it on themselves to threaten citizens directly through the destruction of buildings, and other public infrastructure. While such non state actors have come to characterize the current century they have their origins in much earlier times whenever individuals took action against governments and their follow citizens. Kennedy [4] has commented on the need to make such groups the focus of citizenship education “since understanding such individuals and groups, knowing how to respond to them and knowing how to respond to state actions against them should be part and parcel of any citizenship education program. Citizens must be equipped to handle complex ideas and ideologies if they are to contribute to their societies in a constructive way—traditional approaches to citizenship education may not always achieve this end”.

The kind of changes referred to above may be described in different ways—they may be characterized as economic, social or political or a combination of all of these. Yet what they achieve together are changes to the conditions of citizenship. In these new contexts, citizenship is no longer stable, no longer able to rely on a single national space or remain sheltered from decisions made thousands of kilometers away. A key issued raised by these phenomena is how to prepare citizens to negotiate and respond to these new contexts. What is the role of civic and citizenship education as both a component of the school curriculum and a social construct designed to serve the needs of changing nation states?

The purpose of this paper is to review the status of civic and citizenship education across different regions and within specific national jurisdictions in order to see what changes, if any, have taken place over the past two decades in response to changes in the macro environment. It will do so by drawing on both theoretical and empirical analyses to address the following issues:

- How do theoretical isssues construct civic education?

- How is content in civic education regarded across nations?

- How do education systems make provision for civic education?

- How is civic learning best facilitated and what are the implications for the school curriculum?

2. Theoretical Issues and Civic Education

There are many different ways in which to examine the theoretical issues influencing civic education. In this section, it will be shown how civic and citizenship education and broader conceptions of citizenship can be related. It will also be shown how conceptions of civic and citizenship education itself often serve to construct the school subject in a particular way. Both ways of looking at civic and citizenship education have implications for it as a discipline of inquiry.

Civic and citizenship education can be a policy initiated by a government, a program run in a school, a lesson taught by a teacher or an activity experienced by a student. The common element across these different ways of thinking about civic education is the focus on a special aspect of the school curriculum—the aspect that is specifically concerned with the education of young people to become citizens of the future. Torney-Purta et al. [1] made the point “that civic education content is often less codified and less formalized compared to other subjects” and this was “related to the uncertainty in conceptualizing civic education knowledge due to the amalgamated disciplinary base of the subject and teachers’ varied subject matter backgrounds”. As a part of the school curriculum, therefore, civic education is unlike traditional subjects such as Mathematics, Language or History. That is, it is not so much about mastering a specific body of knowledge or skills—although civic and citizenship education can be knowledge or skills oriented. Rather, it is primarily about understanding the political processes that regulate the daily lives of individuals in any society. This is a key point to understand when considering civic and citizenship education because, as shown above, it is these very processes that have been transformed over the past two decades.

Table 1 summarizes the complex debates that highlight the transformations that have taken place in recent times. The transformations challenge the traditional argument that citizenship is primarily a legal status conferred by one country on the people who live within its borders. This argument is historically located. The history of Europe and North America from the late eighteenth century up to and including the early twentieth century very much focused on the development of individual nations that provided special privileges for their citizens—for example, the right to vote in elections, the right to stand for election, the right to receive economic and social benefits from the government. Citizens are still privileged within the borders of their nations and their rights are guaranteed within these geographic spaces. Yet they must now look beyond borders because the daily lives of citizens can be as much influenced by forces outside those borders as from within.

Table 1.

Changing and conflicting conceptions of citizenship.

| Key ideas on citizenship | Author |

|---|---|

| Individual nations have been the building blocks on which notions of citizenship have been built. Individuals within nations are seen to share common bonds that bring them together to create a distinctive group | See [6,7] on this point |

| The increased economic interaction of nations in the late twentieth century has meant that there is greater interdependence among nations. This interdependence is sometimes referred to as “globalization”. Since citizens now depend not only on their own nation but others as well, ideas have developed that citizenship itself should be broader than a single nation | Ohmae[8] has written about “the end of the nation state” Reid, Gill & Sears [9] have examined the impact of globalization on civic education Altman [10] has written about the apparently diminishing impact of globalization’ in the light of the renewed strength of nation states following the 2008 financial crisis |

| To try and provide a different perspective on citizenship there has been discussion, some people have talked about “global citizenship” or “cosmopolitanism”. The idea has been to suggest a broader understanding of citizenship linked to international rather than national frameworks of involvement and engagement | [11,12] |

The best example of looking beyond borders can be seen in the European Union that has since its beginning promoted the idea of European citizenship. To be a citizen of Europe one must first be a citizen of a member nation. Thus within the European Union, individuals have “two citizenships”: the traditional national citizenship and European citizenship. This is an important point because it means that one citizenship does not cancel out the other but rather one citizenship complements the other. European citizenship also confers additional rights, for example the right to travel across borders of member countries and the right to vote in European elections. The link between citizenship and rights is therefore maintained in this dual citizenship context. The European Union example supports the idea that in these new times, citizenship is a more complex issue that it has been in the past and there should be new ways of thinking about it to meet new developments and issues.

If the idea of citizenship is changing, it follows that ideas about civic and citizenship education should also be changing. Yet such changes are by no means simple. Civic and citizenship education has been embedded in traditional theoretical frameworks that assume it is linked to the needs of individual nations. This is made more complex because there is no single overarching theory—but multiple theories. Civic republicanism, for example, assumes “that individuals come together around common purposes, common values and a common good. The responsibility of citizenship, therefore, is to contribute actively to the “common-wealth” and to recognize at times that individual interests might need to be subjugated to a higher common good” [13]. In opposition to this view is a more full blown liberalism that leads to “a citizenship premised on individual rights giving priority to the interests of individuals rather than the interests of larger groups to which individuals belong. Freedom in all spheres of activity is the catch cry of liberal citizenshi [14]. There are different versions of this liberal conception of citizenship. Howard and Patten [15], for example, refer to neo-liberal discourses that influence civic education pointing to dissolution of restrictions within society that prevent individuals from making their own way in the social and economic spheres of activity. The neo-liberal citizen is a self regulating individual without the need for any government support at all and on whom there are no restrictions. Then there is Rawl’s [16] version of political liberalism that argues for restrictions on the role of the state on what should and should not be taught as part of civic education in a pluralistic society. In Rawl’s view there should be no single ideology guiding civic education apart from shared political values necessary for the maintenance of a democratic society. This is the only way to protect religious pluralism that for Rawls lies outside the political realm.

While these theoretical frameworks contain major differences that are philosophical and ideological in nature, they share one thing in common. They have been applied to civic and citizenship education on the assumption that it is embedded within individual nations. This reflects the historic nation building role of civic and citizenship education but it does not take into account the changing nature of citizenship in a post-modern world. New formulations based on global conceptions of citizenship are making their presence felt [9,17,18] and these provide alternative narratives for citizenship. But the older theoretical frameworks continue to hold sway. Howard and Patten [15], for example, identified neo-liberal influences on recent civic education curriculum in Australia. Lockyer [19] identified strands of both liberalism and civic republicanism in the United Kingdom’s Citizenship curriculum. The focus on human rights in the civic and citizenship education curriculum of many countries is a reflection of commitments to classical liberalism and individual freedom. While there are many international policy instruments that seek to safeguard these rights, the best protections (and indeed the worst abuses) come from within the borders of nation states. The older theoretical frames have not disappeared. In their different ways they continue to exert a nation building influence alongside the newer narratives that provide a broader framework in which to locate citizens’ needs and interests.

A good example of how the old and the new sit side by side can be seen in the Asia Pacific region. Kennedy [13] showed that while liberalizing tendencies had powerfully affected economic growth and development in many Asian countries and that this in turn had led to widespread curriculum reform, that the same liberal tendencies had not been applied to the civic education curriculum. As Kennedy [13] pointed out “there is not a single case represented where the nation state has eased its grip on citizenship education as a major means of inducting young citizens into the culture and values of the nation state itself. This is as true for the United States as it is for the People’s Republic of China, for Australia as it is for Malaysia, for New Zealand as it is for Pakistan”. There can thus be both recognition of the powerful influence of globalizing forces and a deliberate intention to resist such forces in key aspects of a nation’s life. Steiner-Khamsi & Stolpe [20] have demonstrated this same process with particular reference to economic and social development in Mongolia. Here there has been both incorporation of global influences and considerable local agency to resist those influences where local values were seen to be of greater priority. This dual approach to globalization suggests that national and global narratives relating to citizenship will continue to exist side by side rather than one being replaced by the other. It should not, therefore, be assumed that globalization and global citizenship go hand in hand. Indeed the Asian cases demonstrate the opposite—the stronger the processes of globalization the more resistant nation states may be in protecting their future citizens.

A final theoretical issue concerned with civic education relevant to the current theme is the tendency to regard the so called “content” of civic education as more process than specific subject matter. Table 2 shows how different approaches to the assessment of civic education highlight process over content. It is not that civic knowledge is absent altogether from these examples (see the Australian example) but on balance, there is more emphasis on processes than content. This may reflect the fact that in three of the four cases, the assessments apply across countries so the selection of specific content would be very difficult, especially in the international assessments that can apply to over thirty countries. Yet even in the Australian example that does have a specific knowledge domain, the way in which the specific assessment domains are described make it clear that the knowledge being referred to here is almost exclusively national political knowledge. This point is highlighted in Table 3 that compares the key performance measures for Australian students in Year 6 and Year 10. The main point to note about these measures is that they are almost exclusively focused on the national political system and national political institutions. There is one exception, and that is the reference to “analyzing Australia’s role as a nation in the global community”. This may not necessarily be a reference to the impact of globalization or to the changing nature of citizenship in a global context. Rather, it is more likely to focus on the development of Australia in various regional and international contexts (e.g., as a member of the Asia Pacific Education Community and the United Nations). This simply reinforces the point that civic knowledge in these global times is more likely to be constructed as local or at best national. The example used here is from Australia, but it is likely to reflect priorities elsewhere as well. It is national rather than global priorities that continue to dominate civic education. At times, as shown in Table 2, the focus may not even be on knowledge at all, but on processes of participation and engagement.

Table 2.

Process approaches to content in civic education.

| Jurisdiction/Purpose | Domains |

|---|---|

| Australia: National Assessment Program—Civics and Citizenship Education Year 6 Assessment 2004 [21] | Civics: Knowledge and Understanding of Civic Institutions and Processes |

| Citizenship: Dispositions &Skills for Participation | |

| European Union survey of citizenship education [22] | Political Literacy |

| Attitudes/Values | |

| Active Participation | |

| Second IEA Civic Education Study [1] | Democracy/Citizenship |

| International Relations | |

| Social Cohesion/Diversity | |

| International Civic and Citizenship Study [2] | Civic Society & Systems |

| Civic Principles | |

| Civic Participation | |

| Civic Identities |

Table 3.

Key performance measures in the civic knowledge domain: the Australian example [21].

| Civic Knowledge and Understanding of Civic Institutions | |

|---|---|

| Year 6 | Year 10 |

| 6.1: Recognize key features of Australian democracy | 10.1: Recognise that perspectives on Australian democratic ideas and civic institutions vary and change over time |

| 6.2: Describe the development of Australian self-government and democracy | 10.2: Understand the ways in which the Australian Constitution impacts on the lives of Australian citizens. |

| 6.3: Outline the roles of political and civic institutions in Australia | 10.3: Understand the role of law-making and governance in Australia’s democratic tradition. |

| 6.4: Understand the purposes and processes of creating and changing rules and laws | 10.4: Understand the rights and responsibilities of citizens in a range of contexts. |

| 6.5: Identify the rights and responsibilities of citizens in Australia’s democracy | 10.5: Analyse how Australia’s ethnic and cultural diversity contribute to Australian democracy, identity and social cohesion. |

| 6.6: Recognise that Australia is a pluralist society with citizens of diverse ethnic origins and cultural backgrounds | 10.6: Analyse Australia’s role as a nation in the global community |

What can be concluded from this exploration of theoretical issues influencing civic education? First, it has to be recognized that civic and citizenship education has been developed as a strategy used across nations to support the values, structures and priorities of individual nations. Many of the theoretical frameworks referred to above take this as a given in their analyses of citizenship and the various forms it might take within the nation state. Yet citizenship within nation states is no longer something that can be treated in isolation from the broader global environment. Second, there are multiple forces within this environment that often seem to be pulling in different directions. Globalization has tended to locate influence and power outside of nation states but more recent concerns for national security and global financial stability have increased the influence of national governments. Third, traditionally there has been a focus in civic and citizenship education on processes (civic engagement and participation) and any focus on civic knowledge has been on national political knowledge structures rather than on knowledge that would help students understand global processes, structures and systems. In the remainder of this paper it will be important to keep these points in mind because they relate to key issues that will be discussed and they will be reviewed again towards the end of the paper.

3. The Content of Civic Education—A Cross National Perspective

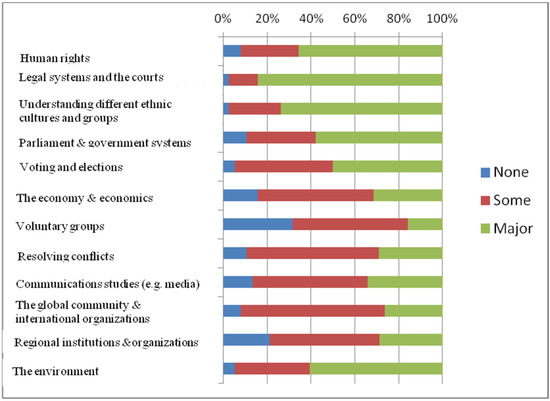

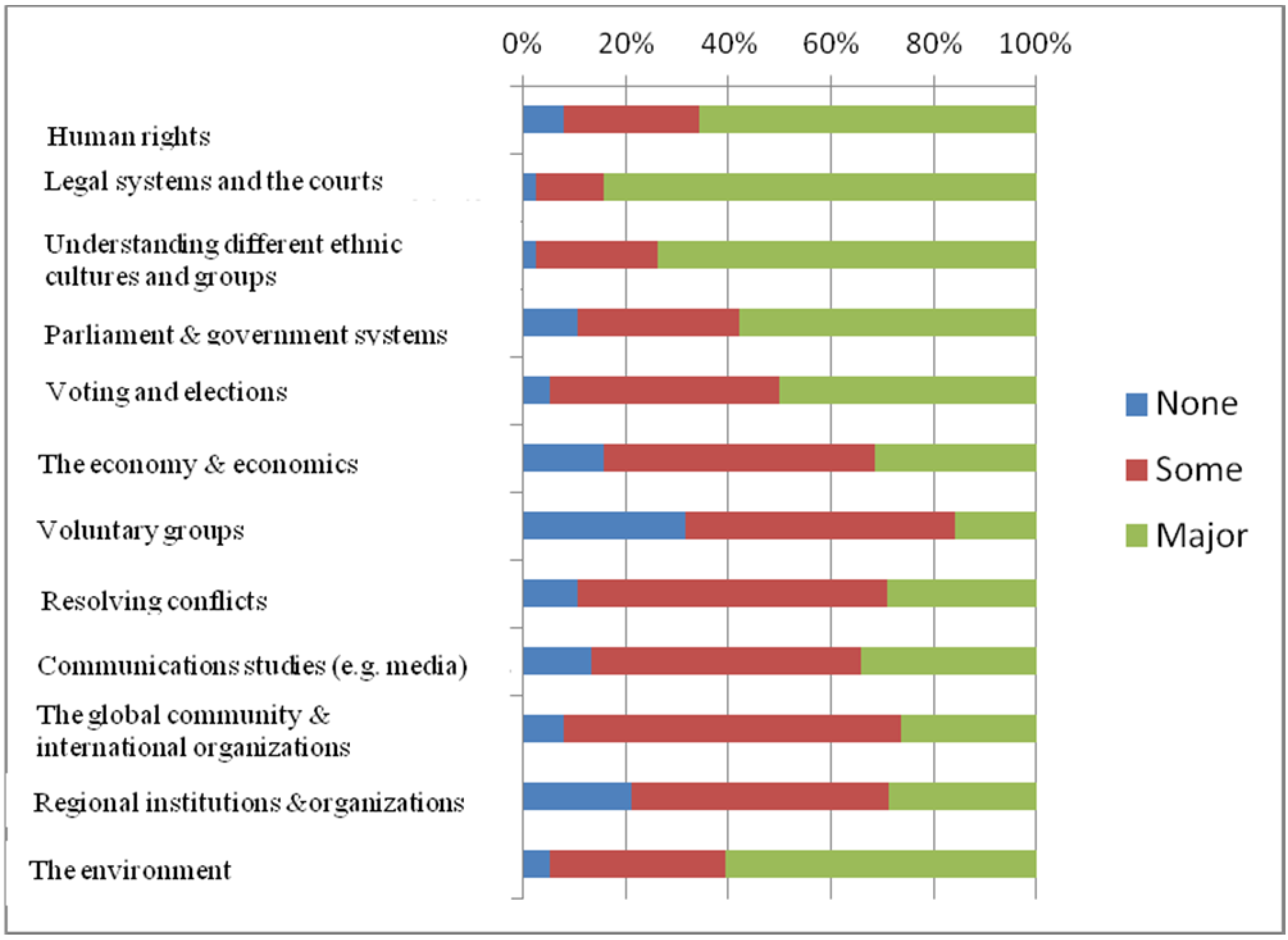

Given the different theoretical frameworks in which civic and citizenship education might be developed, it is important to examine the curriculum itself to see how different countries prioritize specific content for civic education. It is possible to gain an overview of civic education content because of the recently completed International Civics and Citizenship Study [2] that asked the 38 participating countries to provide data on the priorities for civic education. The responses have been summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Curriculum emphases for civic education identified by education systems participating in the international civic and citizenship study countries [2].

Figure 1.

Curriculum emphases for civic education identified by education systems participating in the international civic and citizenship study countries [2].

The first point to note is that while there is some similarities in terms of emphases, there is no common core of civic knowledge that can be identified across participating education systems. There is only one topic that 80% of countries identified as a major emphasis, “Legal Systems and Courts”. “Understanding Different Cultures and Ethnic Groups” was a major emphasis in over 70% of countries. These were followed by “Human Rights” (65.8%), the “Environment” (60.5%) and “Parliament and Government Systems” (57.9%). After these topics there is much less agreement on what represents major emphases across the thirty eight countries.

Perhaps more importantly, however, topics that might reflect a more international or global perspective—“The Global Community and International Organizations” and “Regional Institutions and Organizations”—are seen as major emphases in civic education for less than 30% of the participating countries. The same topics do not feature at all in 7.9% and 21% of countries respectively. Other topics such as “Human Rights” and the “Environment” may well have global dimensions, but the other topics where there is a major emphasis appear to be more related to local civic organizations or issues. Based on this analysis, therefore, it seems that local rather than global perspectives continue to dominate the civic education curriculum suggesting that the preparation of future citizens continues to be focused on national citizenship. This analysis supports the trend shown in Table 3 referring specifically to the case of Australia where the focus of the civic component of the national civic assessment was also on national and local political systems.

Another perspective on the importance of national priorities in civic and citizenship education can be seen from countries’ endorsement of the importance of developing a sense of national identity and allegiance. 47% of countries indicated that this was a major emphasis in terms of civic processes emphasized in civic education, 42% of countries indicated there was some emphasis on it and 11% of countries indicated there was no emphasis on it [2]. This is not to say that there are not other persepctivres included in national curriculum or that if the question had been asked about global persepctives that it may not have received a positive response. For example, in the United Kingdom’s Citizenship curriculum for students to be assessed at Level 6 and above, they must be able to “show understanding of interdependence, describing interconnections between people and their actions in the UK, Europe and the wider world” [23]. Yet national perspectives remain dominant in civic education even where there may be a recognition that students should look beyond the borders of their respective countries.

Finally, it is also possible to examine the way teachers participating in the ICCS viewed the importance of civic content. Table 4 shows content areas and teachers’ responses to them.

Table 4.

Teachers’ perceptions of important aims for civic education.

| Aims for civic education | Percentages of teachers considering these aims for civic education important | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 30 countries) | ||

| International Average (%) | Range (%) | |

| Promoting knowledge of social, political and civic institutions | 33 | 16–57 |

| Promoting respect for and safeguard of the environment | 41 | 22–61 |

| Promoting the capacity to defend one’s own point of view | 20 | 4–8 |

| Developing students’ skills and competencies in conflict resolution | 41 | 21–73 |

| Promoting knowledge of citizens’ rights and responsibilities | 60 | 37–73 |

| Promoting students’ participation in the local community | 16 | 2–40 |

| Promoting students’ critical and independent thinking | 52 | 19–84 |

| Promoting students’ participation in school life | 19 | 9–5 |

| Supporting the development of effective strategies for the fight against racism and xenophobia | 10 | 1–31 |

| Preparing students for future political participation | 7 | 1–19 |

From the perspective of teachers in 30 countries, the top four aims of civic education are “Promoting knowledge of citizens” rights and responsibilities (60%), “Promoting students’ critical and independent thinking” (52%) and “Promoting respect for and safeguard of the environment”/“Developing students skills and competencies in conflict resolution” (41% each). Given that these were forced category choices, teachers did not get the opportunity to express their views about global citizenship or global issues. Nevertheless, the focus of these top four aims clearly show that civic and citizenship education in these different national contexts emphasise the social and the personal aspects of the subject. It seems that for teachers, equipping individual students with skills that will help them negotiate a complex and uncertain world, is a priority. It is of interest to note that “Promoting knowledge of social, political and civic institutions” rates relatively poorly (33% of teachers on average regard it is important in at least one country the figure is as low as 16% of teachers. Lower still is any focus on “Preparing students for future political participation” with an international average of only 7% of teachers seeing it as important. This suggests that the political roles of citizens are not regarded as important by teachers, particularly when compared to the personal and social roles that students can play as future citizens. Finally, it can be seen that processes rather than specific content dominate civic education. Yet how are these aims realized in the actual curriculum? This issue will be addressed in the following section.

4. Curriculum Structures for Civic Education

The organization of the school curriculum highlights and what is considered valued knowledge for young people. It would be likely across countries to find that Mathematics, Science and mother tongue Language will be separate subjects with specific time allocations. In addition, perhaps History and Geography or some integrated version such as Social Studies will also find a similar place. Then there may also be room for Physical Education, Art, Music and Health Education. Where does Civic Education fit alongside these formal subjects in the school curriculum?

Kennedy [14] proposed a framework for considering the curriculum status of civic education. It highlighted four possible modes of delivery: as a single subject, taught through other subjects such as History and Geography, integrated across all subjects or as an extra curricular activity. In a subsequent study, Fairbrother and Kennedy [24] showed students who experienced Civic Education as a separate subject did produce higher scores on civic learning outcome measures and the differences were statistically significantly different from those of students who experienced Civic Education in other modes. Yet the mode of curriculum delivery did not account for a significant proportion of the variance in students’ learning outcomes. Other factors need to be identified that impact on learning.

In the recent ICCS [2] (Table 2) the curriculum delivery modes themselves were re-categorized and expanded from Kennedy’s [14] four to eight:

- Specific subject (compulsory or optional);

- Integrated into several subjects;

- Cross curricular;

- Assemblies and special events;

- Extra- curricular activities;

- Classroom experience/ethos; and

- Other.

The interesting point to note about participating countries’ responses to these curriculum delivery categories is that apart from compulsory/optional choice they were not seen to be mutually exclusive. Thus all countries indicating Civic Education was a compulsory single subject (representing 45% of the total number of countries) also indicated other curriculum delivery modes were used as well. For example, Chinese Taipei selected “compulsory specific subject”, “cross curricular”, “assemblies and special events”, “extra-curricular activities” and “classroom experiences/ethos” whereas Estonia selected “compulsory specific subject”, “integrated into several subjects” and “cross curricula”. There is, therefore, not a single curriculum delivery mode for civic education but multiple modes. This is also true where Civic Education is not a single subject (see, for example, Hong Kong, Finland and Denmark [2] Table 2). A key point that arises from this phenomenon is to consider what it means for Civic Education as a discipline.

One observation to make on this issue is that the new curriclum delivery categories addded by the ICCS were towards the informal civic learning end of the curriculum. This suggests that while there may be formal curriuclum content to be covered (for example 45% of countries indicated Civic Education was a “compulsory specific subject” and 81% indicated it was “integrated into several subjects”) there were also aspects of Civic Ecuation that fell outside of these subject boundaries into more informal activities (for example assemblies, extra curricular activities and classroom ethos). This makes Civic Education somewhat exceptional since its boundaries are so flexible. It also raises the important question of civic learning and how this can best be facilitated for curriuclum exepriences that extend beyond the formal curriuclum. . This issue will be taken up in the following section.

5. Facilitating Civic Learning and the Implications for the School Curriculum

Researchers on civic learning—including those responsible for the ICCS—have tended to focus on those structural variables that influence student learning—socioeconomic status, gender, immigrant status, etc. These are always telling and are important control variables, but the issue of interest to teachers is what can be done to promote civic learning both within classrooms and beyond them into schools and the community. The responses in the research literature tend to suggest that there are instructional strategies and school activities that do support student’s civic learning. An “open classroom climate” within classrooms and the use of School Parliaments involving students are two processes that have been found to be positively related to students’ civic learning [1]. These are things that teachers and schools can well manage and go beyond the structural and demographic characteristics of students. There are other strategies that were identified in the context of the IEA Civic education study [1].

Turney-Purta and Barber, [25] reported that reading newspapers is a moderate predictor of students’ likelihood to vote (βs across their European sample were ≥ 10, ≤ 21). Torney-Purta et al [1], reported that the frequency of watching TV and news amongst the international sample was also a moderate predictor of students’ likelihood to vote in the future (β = 13). These could be activities that take place out of school. Yet given that there are differential levels of trust in the media across countries they could equally well take place within school if they were developed as instructional and learning activities. Husfeldt, Barber and Torney-Purta [26] developed a new Trust in Media Scale but have also raised the question of whether students are able to apply critical skills to the task. Amadeo, Torney-Purta and Barber [27] have shown the positive relationship between media consumption and both students’ civic knowledge and their attitude to future civic engagement. Torney-Purta and Barber [25] have pointed out “school-based programs that introduce students to newspapers and foster skills in interpreting political information may be of value”. This may be a particularly important thing to do for students whose home environments do not provide them with these informal learning opportunities. These are more examples of how schools and teachers can make a difference to civic learning.

This consideration of civic learning raises an important question about the nature of civic and citizenship education as a “discipline”. It is concerned with both “content” and “pedagogy”, and it is not enough to consider either in isolation. The influential report, The Civic Mission of Schools [28,29] made this point very strongly. The report argued that while civic knowledge is an essential part of any civic education, it cannot be delivered in such a way as to alienate students or lead them to become disengaged from learning. The kind of teaching and learning strategies referred to above are as much a part of the discipline as the specific knowledge itself. Pedagogy and content must be integrated for civic education: what needs to be learnt should be constructed in a learning environment that is at once relevant, meaningful and engaging to students. Because civic education, in liberal democracies at least, is about supporting democratic structures and systems, then teaching strategies need also to be democratic otherwise there will be a conflict between the content and the pedagogy. This is an important issue for the development of civic and citizenship education in the future.

6. Conclusions

The many changes in the external environment have focused attention on civic and citizenship education over the past two decades. Many countries have responded to these changes by reinforcing the civic and citizenship education curriculum but there has been no standard approach internationally. Diversity rather than uniformity is the main characteristic of the civic curriculum. In terms of aims, teaching strategies and delivery mechanisms, there is considerable variability across countries. Successive international assessment studies have not isolated the variables that can account for successful civic learning. Rather, a combination of structural characteristics (for example, socioeconomic status, gender and immigrant status) combined with student focused instructional strategies and democratic decision making processes seem to be the most likely explanations for different levels of civic learning. Yet much remains to be done to identify other variables that impact on student learning in civic education.

In terms of specific content for civic education, it seems that at the present time, despite the significant changes to the external environment, the focus is on national political structures and systems. While more detailed examination of specific curricula is needed to confirm this finding, it does seem that in a number of jurisdictions at least the emphasis is on the social and personal aspects of civic education rather than on the political or global aspects. This is despite the changes that were documented at the beginning of this paper. Global citizenship, while the vision of some academics and community supporters, remains at some distance from national curricula where, to use Keating’s [5] terms, “the nation-state model continues to have a grip on the intellectual imagination”

References

- Torney-Purta, J.; Lehmann, R.; Oswald, H.; Schulz, W. Citizenship and Education in Twenty-Eight Countries: Civic Knowledge and Engagement at Age Fourteen; IEA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, W.; Ainley, J.; Fraillon, J.; Kerr, D.; Losito, B. Initial Findings from the IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study; IEA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.H. Education Reform and Education Policy in East Asia; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, K. Neo-statism and post-globalization as contexts for new times. In Globalisation, the Nation-State and the Citizen: Dilemmas and Directions for Civics and Citizenship Education; Reid, A., Gill, J., Sears, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, M. Rescaling Europe. Perspect. Eur. Polit. Soc. 2009, 10, 1570–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A. Education and state formation in Europe and Asia. In Citizenship Education and the Modern State; Kennedy, K., Ed.; Falmer: London, UK, 1997; pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, C. Concentric, overlapping and competing loyalties and identities. In Nationalism in Education; Schleicher, K., Ed.; Peter Lang: Frankfort, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmae, K. The End of the Nation State; Harper Collins Publisher: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, A.; Gill, J.; Sears, A. Globalisation, the Nation-State and the Citizen: Dilemmas and Directions for Civics and Citizenship Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, R. Globalization in retreat—Further geopolitical consequences of the financial crisis. Foreign Aff. 2009, 88, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, H. Educating the European citizen in the global age: Engaging with the post-national and identifying a research agenda. J. Curric. Stud. 2009, 41, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Anker, C. Transnationalism and cosmopolitanism: Towards global citizenship? J. Int. Polit. Theory 2010, 6, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K. Globalized economies liberalized curriculum reform and national citizenship education: New challenges for national citizenship education. In Citizenship Curriculum in Asia and the Pacific; Grossman, D.L., Lee, W.O., Kennedy, K., Eds.; Comparative Education Research Centre: Hong Kong, China, 2008; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, K.J. The citizenship curriculum: Ideology, content and organization. In The SAGE Handbook Of Education for Citizenship And Democracy; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 483–491. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, C.; Patten, S. Valuing civics: Political commitment and the new citizenship education in Australia. Can. J. Educ. 2006, 29, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. Political Liberalism; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Keyman, F.; Icduygu, A. Citizenship in a Global World: European Questions and Turkish Experiences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Isin, E. Democracy, Citizenship and the Global City; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lockyer, A. Introduction and review. In Education for Democratic Citizenship—Issues of Theory and Practice; Lockyer, A., Ed.; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Aldershot, UK, 2003; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner-Khamsi, G.; Stolpe, I. Educational Import: Local Encounters with Global Forces in Mongolia; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerial Council on Education, Employment Training, and Youth. National Assessment Program—Years 6 and 10 Civics and Citizenship Report; Curriculum Corporation: Melbourne, Australia, 2006. Available online: http://www.mceetya.edu.au/verve/_resources/CC04_Yr_6_SRM_Part-A.pdf (accessed 19 June 2012).

- European Commission (Directorate-General for Education and Culture). Citizenship Education at School in Europe; Eurydice European Unit: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. Available online: http://www.moec.gov.cy/programs/eurydice/publication.pdf (accessed 19 June 2012).

- Attainment Target for Citizenship Homepage. Available online: http://www.teachfind.com/qcda/attainment-target-citizenship-subjects-key-stages-1-2-national-curriculum (accessed on 15 June 2012).

- Fairbrother, G.; Kennedy, K. Civic education curriculum reform in Hong Kong: What should be the direction under Chinese sovereignty? Cambridge J. Educ. 2012, in press.. [Google Scholar]

- Torney-Purta, J.; Barber, C. Democratic School Engagement and Civic Participation among European Adolescents; IEA: Amesterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. Available online: http://www.jsse.org/2005/2005-3/judith-torney-purta-carolyn-barber-democratic-school-engagement-and-civic-participation-among-european-adolescents (accessed on 15 June 2012).

- Husfeldt, V.; Barber, C.; Torney-Purta, J. Students’ Social Attitudes and Expected Political Participation: New Scales in the Enhanced Database of the IEA Civic Education Study; Civic Education Data and Researcher Services: College Park, MD, USA, 2005. Available online: http://www.terpconnect.umd.edu/~jtpurta/Original%20Documents/CEDARS%20new%20scales%20report.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2012).

- Amadeo, J.; Torney-Purta, J.; Barber, C.H. Attention to Media and Trust in Media Sources: Analysis of Data from the IEA Civic Education Study; The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement: College Park, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, J. Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools; The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement: College Park, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie Corporation of New YorkThe Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE)The Civic Mission of Schools; Carnegie Corporation of New York and CIRCLE: College Park, MD, USA, 2003.

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).