Creating Written Stories for Primary School Students Based on Personalized Mnemonics: The Case of One Lithuanian School

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

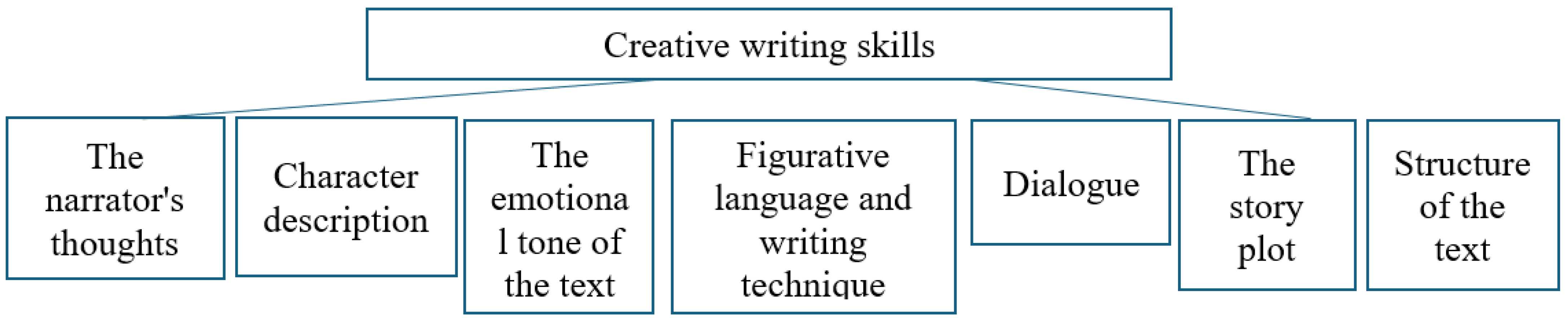

2.1. The Concept of Developing Creative Writing Skills in Primary School Pupils

2.2. Methods of Support for Developing Creative Writing Skills in Primary School Students

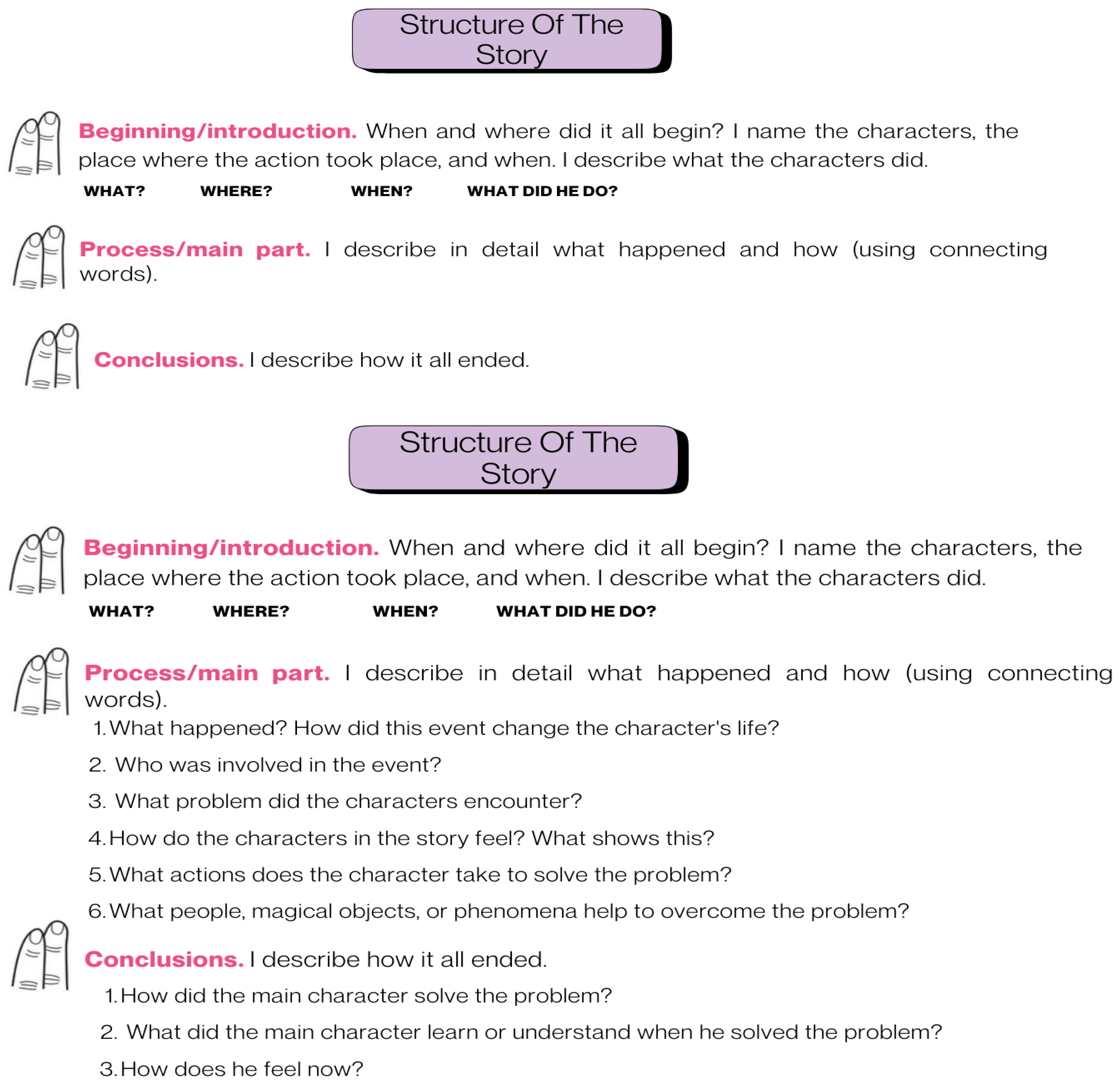

2.3. The Help and Benefits of Writing Mnemonics

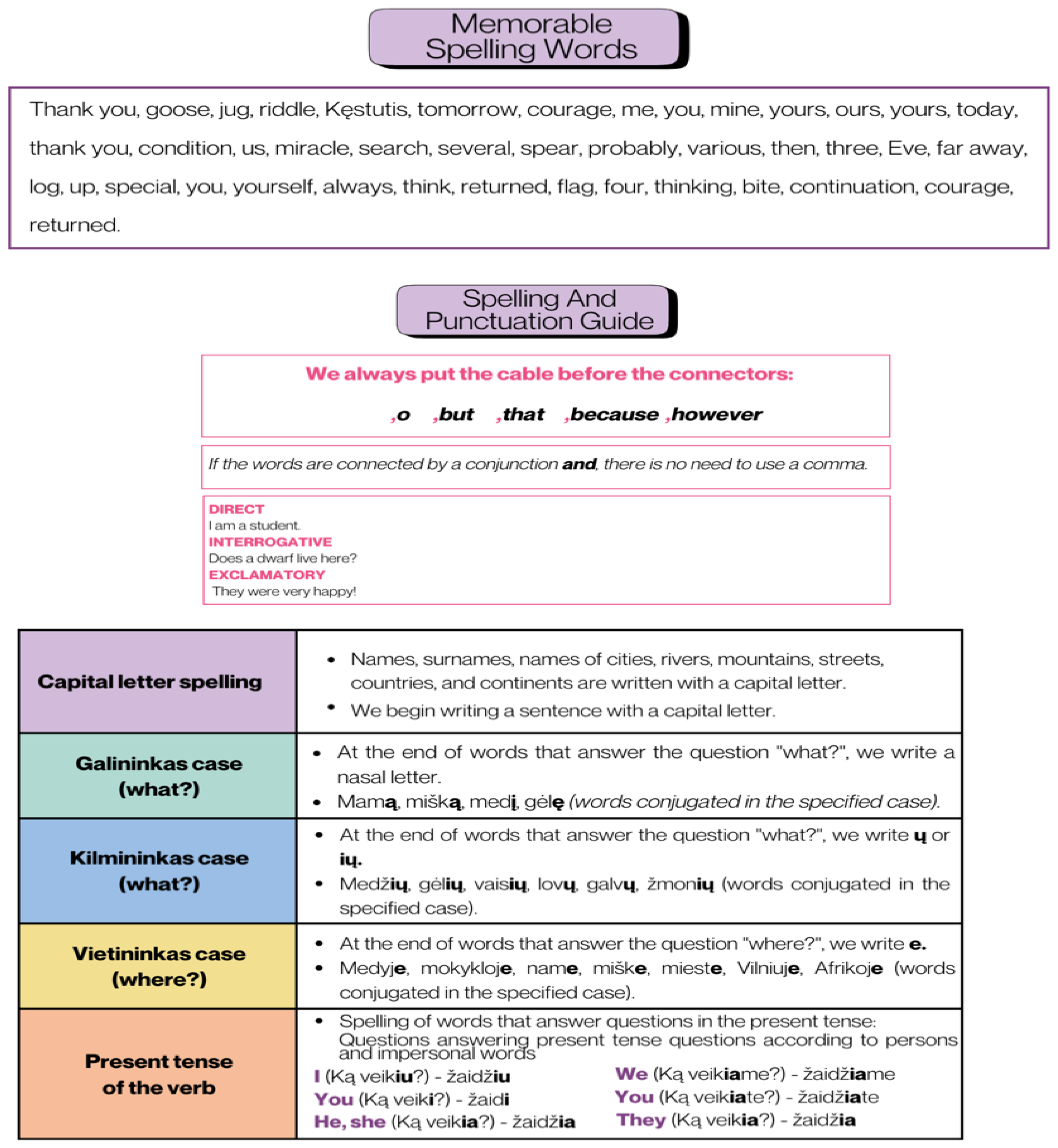

- Acrostic mnemonic—a specific word is used, in this case, it may be related to the type or theme of the text, where each letter represents a piece of important information that needs to be used when creating the story (the most important parts of the story, key words describing the characters).

- Keyword mnemonic—words with similar sounds and meanings are provided.

- Locus mnemonic—names of various places associated with children’s experiences are provided.

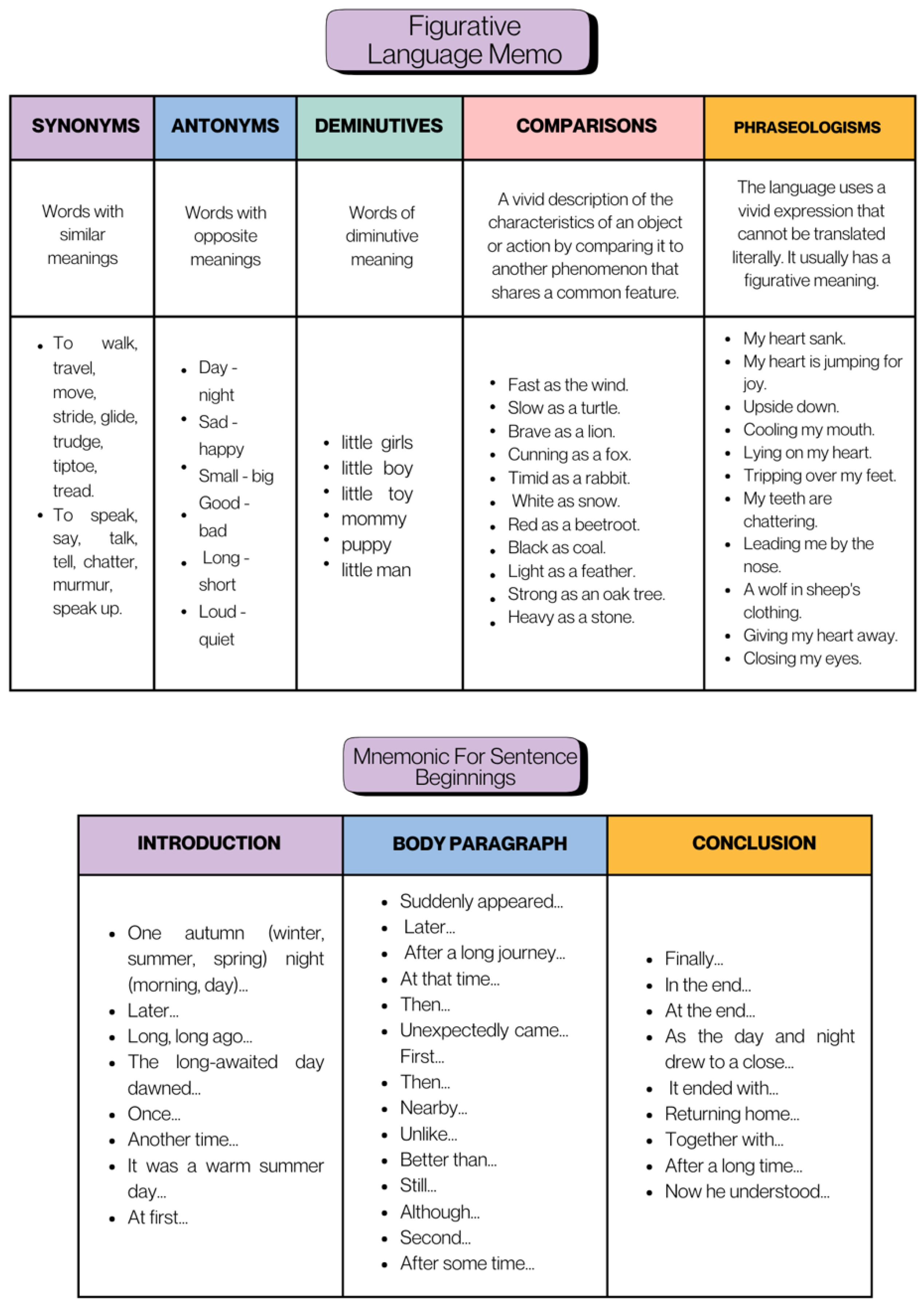

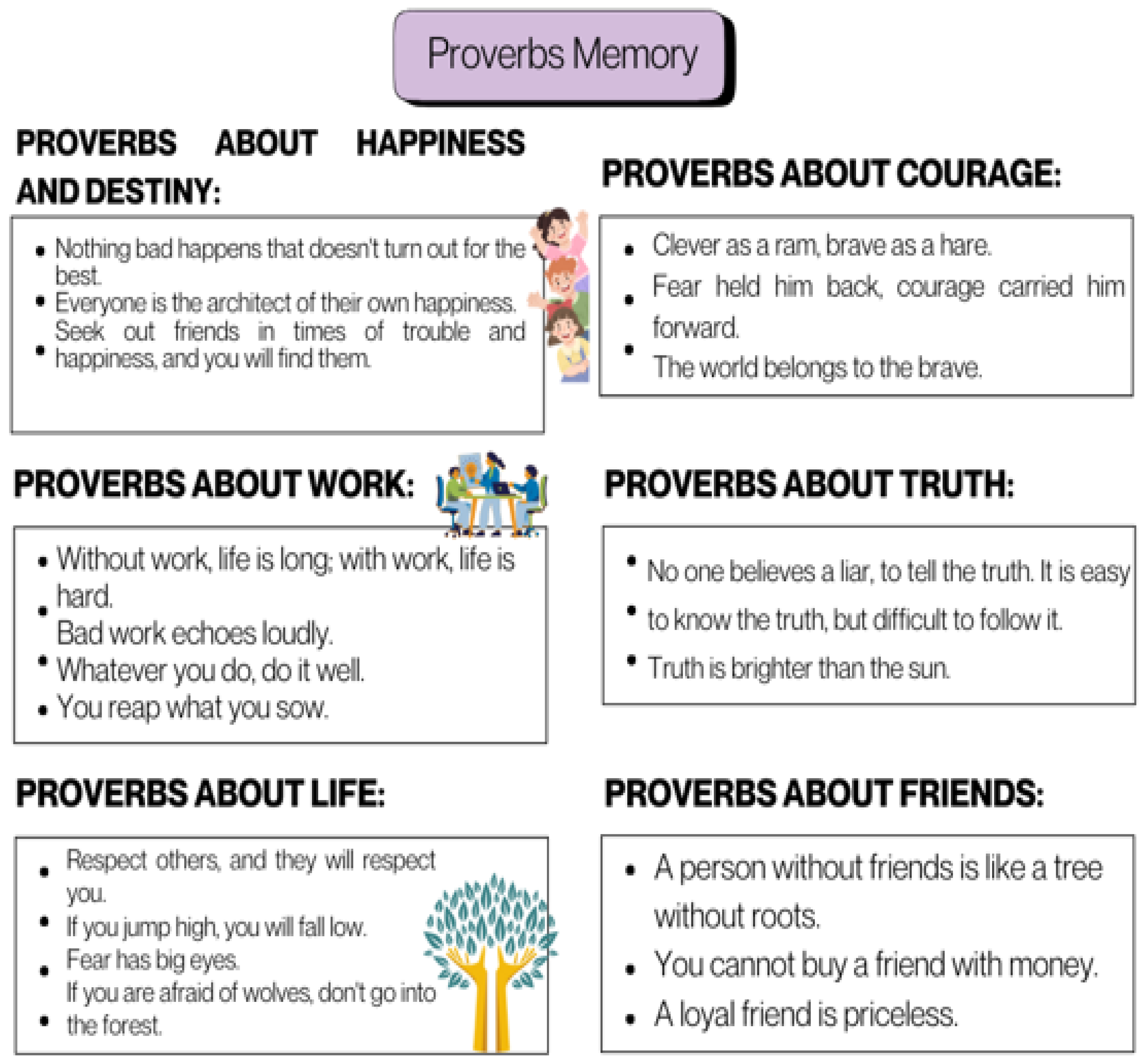

- Stylistic cohesion—various conjunctions, sentence starters, and other phrases that allow logical sentences to be combined into a coherent text.

- Characterization—various elements that help to create a vivid, attention-grabbing character.

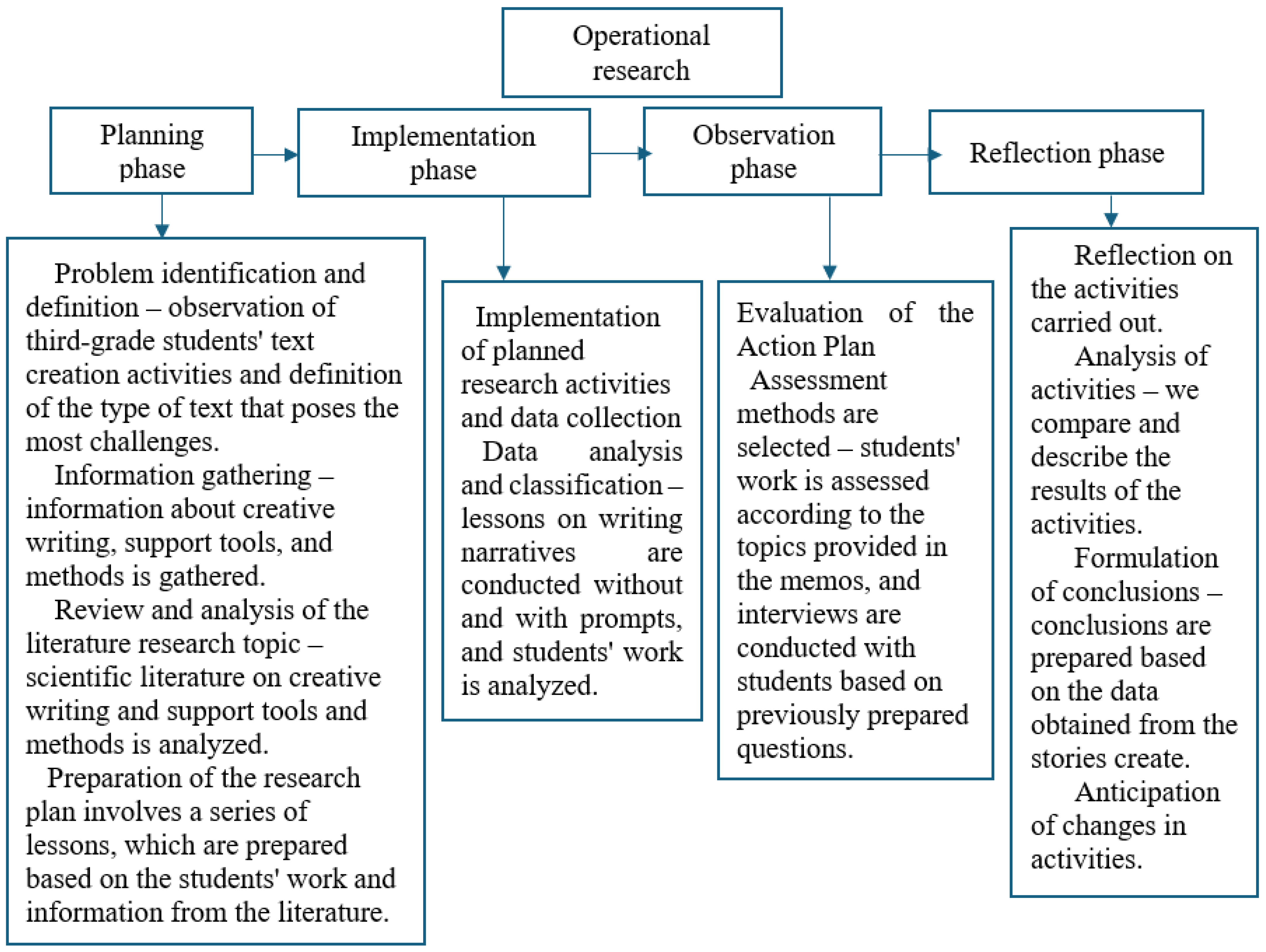

3. Developing Creative Writing Skills in Primary School Pupils Using Mnemonics: Empirical Research Methodology

- Qualitative research paradigm. Bryda and Costa (2023) argue that the variety of contemporary qualitative data analysis methods is very large, involving the analysis of interviews, texts, and visual material. In our study, an activity study was conducted several times in the same class, during which students wrote creative works using personalized mnemonics. The creation and application of personalized mnemonics in the educational process corresponds to the elements of developing transformative practical experience (Fantinelli et al., 2024). In the empirical part of the study, we present an analysis of creative writing works at different stages according to the cheat sheets used and certain words used in them. This study does not claim to cover the entire sample, but it reveals educational practices and shows certain details that are directly related to helping specific students and how that help can change specific student work (in this case, creative writing) and contribute to the growth of a student’s personal achievements in the field of creative writing. A qualitative thematic analysis of the content (Fantinelli et al., 2024; Mack et al., 2005; Saldana, 2010) of creative writing assignments was carried out, analysing and grouping the results of each student according to the personalized mnemonics.

- What are the benefits of using mnemonic devices to develop the storytelling skills of primary school students?

- What should be taken into account when preparing personalized mnemonics for developing the creative writing skills of primary school students?

- How much do spelling mnemonic devices help children reduce spelling errors when writing a story, compared to traditional teaching methods?

- to theoretically substantiate the concept of developing creative writing skills with the help of aids;

- to examine the experience of developing the writing skills of third-grade students when using cheat sheets;

- to compare students’ creative writing skills and identify changes when writing without and with the use of cheat sheets.

- 3rd-grade students with higher creative writing skills in the Lithuanian language;

- 3rd-grade students with basic creative writing skills in Lithuanian;

- 3rd-grade students with satisfactory creative writing skills in Lithuanian;

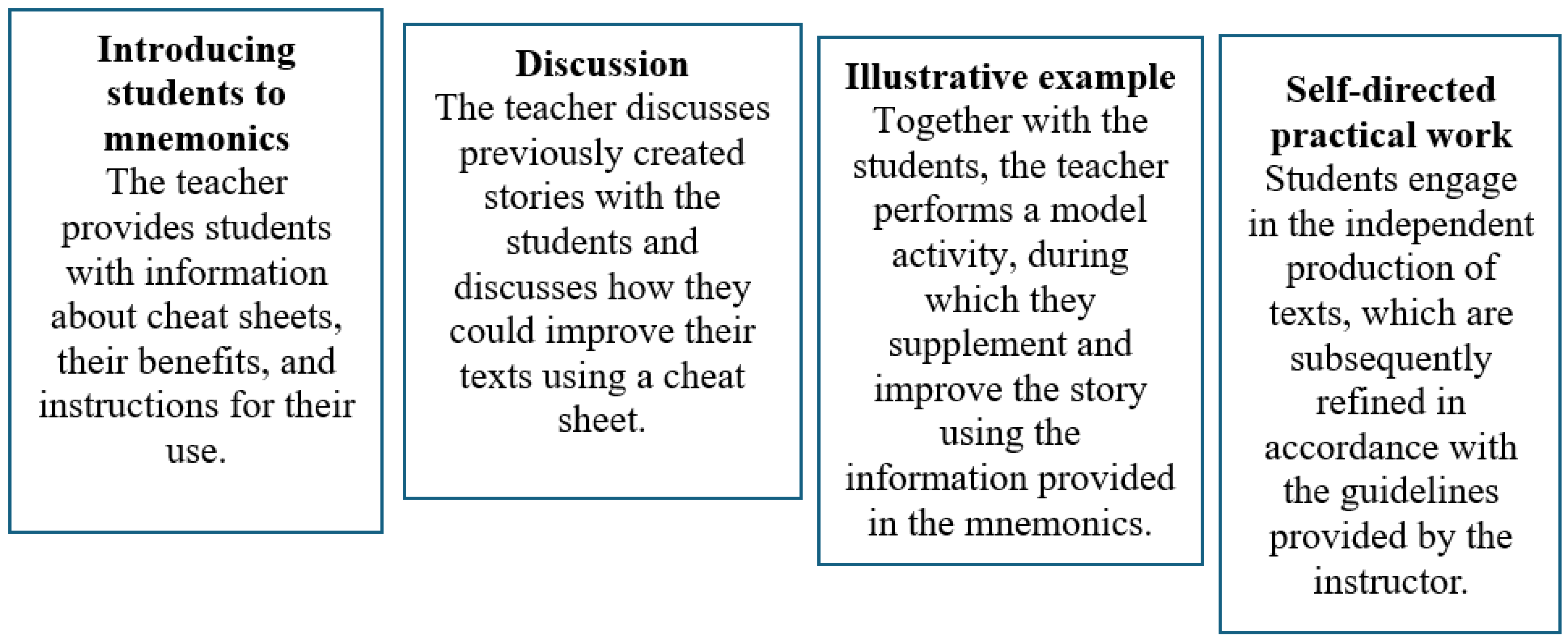

3.1. A Description of the Research Process

3.2. Research Ethics

4. Analysis of Empirical Research Results

4.1. Analysis of Diagnostic Research Data

4.2. Analysis of the Results from the First Stage of the Study, During Which Mnemonics Were Used in Creative Writing Tasks

4.3. Analysis of the Results of the Second Stage of the Study, in Which Mnemonics Were Used During Creative Writing Tasks

- story structure;

- revelation of the theme;

- clarity and coherence of the text;

- correct spelling and punctuation.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., & Loewenstein, G. (2020). Secrets and likes: The drive for privacy and the difficulty of achieving it in the digital age. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 30(4), 736–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsola, M. K., & Odeyemi, E. O. (2014). Effects of mnemonic and prior knowledge instructional strategies on students achievement in mathematics. International Journal of Education and Research, 2(7), 675–688. [Google Scholar]

- Alied, N. A., Alkubaidi, M. A., & Bahanshal, D. A. (2022). The use of blogs on EFL students’ writing and engagement in a Saudi private school. Journal of Education and Learning, 11(4), 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhaldi, A. A. (2023). The impact of technology on students’ creative writing: A case study in Jordan. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 13(3), 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mukhallafi, T. R. (2022). The impact of information technology on developing creative writing skills and academic self-efficacy for undergraduate students. International Journal of English Linguistics, 12(1), 12–29. Available online: https://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ijel/article/view/0/46253 (accessed on 30 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Aluwihare-Samaranayake, D. (2012). Ethics in qualitative research: A view of the participants’ and researchers’ world from a critical standpoint. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(2), 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arni, D. N. B. A., & Aziz, A. A. (2024). Utilising journaling technique to enhance creative writing skills among primary school students. Jurnal Pendidikan, 49(1), 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Assemakis, K. (2023). Student teachers as creative writers: Does an understanding of creative pedagogies matter? Literacy, 57(1), 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, O., & Şahin, H. (2021). Review of primary school English coursebooks in terms of creative writing activities. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 8(3), 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, G., Khosronejad, M., Ryan, M., Kervin, L., & Myhill, D. (2024). Teaching creative writing in primary schools: A systematic review of the literature through the lens of reflexivity. The Australian Educational Researcher, 51, 1311–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezan, O., Krishen, A. S., & Garcera, S. (2023). Back to the basics: Handwritten journaling, student engagezment, and bloom’s learning outcomes. Journal of Marketing Education, 45(1), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J. (2023). Key strategies for a focus on creative writing in ELT–Using mentor texts in teacher education. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 11(2), 28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bryda, G., & Costa, A. P. (2023). Qualitative research in digital era: Innovations, methodologies and collaborations. Social Sciences, 12(10), 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bukantienė, J., Girdzijauskienė, R., Jarienė, R., Penkauskienė, D., & Sruoginis, L. V. (2013). Mokinių kūrybiškumo ugdymo lietuvių (gimtosios) kalbos pamokose metodika [Methodology for developing students’ creativity in Lithuanian (native) language lessons]. Šiuolaikinių Didaktikų Centras. [Google Scholar]

- Carignan, I., Beaudry, M.-C., & Larose, F. (2016). La recherche-action et la recherche-développement au service de la littératie. Les Éditions de L’université de Sherbrooke. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicho, K. Z. H., & Zrary, M. O. H. (2022). Using visual media for improving writing skills. Canadian Journal of Language and Literature Studies, 2(4), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioca, L.-I., & Nerișanu, R. A. (2020). Enhancing creativity: Using visual mnemonic devices in the teaching process in order to develop creativity in students. Sustainability, 12(5), 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demïrbaş, İ., & Şahïn, A. (2023). The effect of digital stories on primary school students’ creative writing skills. Education and Information Technologies, 28(7), 7997–8025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, C., & Ackermann, F. (2018). Theory into practice, practice to theory: Action research in method development. European Journal of Operational Research, 271(3), 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantinelli, S., Cortini, M., Di Fiore, T., Iervese, S., & Galanti, T. (2024). Bridging the gap between theoretical learning and practical application: A qualitative study in the Italian educational context. Education Sciences, 14(2), 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaižauskaitė, I., & Valavičienė, N. (2016). Socialinių tyrimų metodai: Kokybinis interviu [Social research methods: Qualitative interviews]. Registrų Centras. [Google Scholar]

- Göçen, G. (2019). The effect of creative writing activities on elementary school students’ creative writing achievement, writing attitude and motivation. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 15(3), 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. (2023). The contribution of blog-based writing instruction to enhancing writing performance and writing motivation of Chinese EFL learners. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1069585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A. G., Holmes, A., & Pollock, B. (2021). Memory aids as a disability-related accommodation? Let’s remember to recommend them appropriately. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 36(3), 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2017). The practice of qualitative research: Engaging students in the research process (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, I. H. (2024). Creative writing instruction for primary students: An in-depth analysis in the context of curriculum reform in Vietnam. International Online Journal of Primary Education, 13(2), 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., & Renandya, W. A. (2018). Exploring the integration of automated feedback among lower-proficiency EFL learners. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 14(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, B. (2020). Constructing digital ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ gamebooks to enhance creative writing and collaboration skills. In K.-M. Frederiksen, S. Larsen, L. Bradley, & S. Thouësny (Eds.), CALL for widening participation: Short papers from EUROCALL 2020 (pp. 120–124). Research-Publishing.net. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Sanchis, E., Echegoyen-Sanz, Y., & Martín-Ezpeleta, A. (2025). Primary school teachers’ creative self-perception and beliefs on teaching for creativity. Education Sciences, 15(2), 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė, D., Jašinauskas, L., & Kudinovienė, J. (2025). Action research-based practices in primary education. Educational contexts and teachers’ experiences. Rankraštis. Vytauto Didžiojo Universitetas. [Google Scholar]

- Jamik, H. N., & Soeharno, S. (2020). The implementation of mnemonic method to improve the primary school learner’ s English writing skills. Journal of Primary Education, 9(4), 422–428. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumawardhani, P. (2020). The use of flashcards for teaching writing to English young learners (EYL). Scope: Journal of English Language Teaching, 4(1), 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B. P. (2024). Writing strategies for elementary multilingual writers: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 14(7), 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietuvos bendrosios programos [Lithuanian framework programmes]. (2022). Nacionalinė švietimo agentūra.

- Liu, D., He, P., & Yan, H. (2023). An empirical study of schema-associated mnemonic method for classical Chinese poetry in primary and secondary education based on cognitive schema migration theory. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 20720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, N., Woodsing, C., Mac Qeen, K., Guest, G., & Namey, E. (2005). Qualitative research methods: A data collector‘s field guide. FHI. [Google Scholar]

- Mangion, M., & Riebel, J. A. (2023). Young creators: Perceptions of creativity by primary school students in Malta. Journal of Intelligence, 11(3), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, K. A., Lee, V. J., Gentile, C., Hanna, C., & Montgomery, A. (2024). Empowering young writers: A multimodal case study of emergent writing in urban preschool classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 53(6), 2117–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathura, S., & Zulu, F. Q. B. (2021). Using flashcards for English second language creative writing in Grade 1. Reading & Writing-Journal of the Reading Association of South Africa, 12(1), 298. [Google Scholar]

- Matulaitienė, J. (2021). Metamokymasis pradiniame ugdyme: Mokslinės literatūros analizė [Metacognition in primary education: An analysis of scientific literature]. Pedagogika, 143(3), 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (Vol. 11, Issue 2, pp. 64–81). Jossey-Bass A Wiley Brand. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, A., & Ocetkiewicz, I. (2021). Creativity for sustainability: How do polish teachers develop students’ creativity competence? Analysis of research results. Sustainability, 13(2), 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paldy, P., Sthevaniocy, Y. R., Baharuddin, M. R., & Yunus, R. Y. I. (2025). Creating engaging flashcard materials for young learners: A developmental study on English language teaching in primary schools. Journal of Languages and Language Teaching, 13(1), 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methoods (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, A. L. (2015). Mnemonics in education: Current research and applications. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 1(2), 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhanti, D. (2024). The role of reflective journaling in creative writing learning. Journal of Social and Scientific Education, 1(1), 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgatlioglu, M., & Ulusoy, M. (2022). The effect of activity-based poetry studies on reading fluency and creative writing skills. International Journal of Progressive Education, 18(3), 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupšienė, L. (2007). Kokybinių tyrimų duomenų rinkimo metodologija [Qualitative research data collection methodology]. Klaipėdos Universitetas. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana, J. (2010). The coding manual for qalitative researchers. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Saylik, A. (2014). Pradinių klasių mokinių kūrybinio rašymo gebėjimų ugdymas naudojant interaktyviąją lentą [Developing creative writing skills in primary school students using an interactive whiteboard] [Daktaro disertacija, Lietuvos Edukologijos Universitetas]. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. J. (2022). Working memory training and explicit teaching: A transdisciplinary approach to reading intervention. Australian Catholic University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarūnaitė, G. (2025). Pradinių klasių mokinių kūrybinio rašymo gebėjimų ugdymas naudojantis atmintinėmis [Developing creative writing skills in primary school students through mnemonics]. Vytauto Didžiojo Universitetas. [Google Scholar]

- Širiakovienė, A., Bilbokaitė, R., & Rašimaitė, G. (2016). Pradinių klasių mokytojų požiūris į mokinių kūrybiškumo ugdymą muziejine edukacija [Primary school teachers’ attitudes towards fostering creativity in pupils through museum education]. Mokytojų ugdymas, 26(1), 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Q. (2024). Creativity in the digital canvas: A comprehensive analysis of art and design education pedagogy. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications, 15(6), 942–951. [Google Scholar]

- Ulu, H. (2019). Examining the relationships between the attitudes towards reading and reading habits, metacognitive awarenesses of reading strategies, and critical thinking tendencies of pre-service teachers. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 6(1), 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, A., & Uslu, N. A. (2021). Improving primary school students’ creative writing and social-emotional learning skills through collaborative digital storytelling. Acta Educationis Generalis, 11(2), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaicekauskienė, L., Vukotić, V., Čičirkaitė, R., & Nevinskaitė, L. (2022). Lietuvių kalba kaip klaida. Raštingumo samprata ir kalbos taisymai mokykloje [Lithuanian language as a mistake. The concept of literacy and language corrections at school] (Specialusis Taikomoji kalbotyra numeris, Nr. 18). Available online: https://www.zurnalai.vu.lt/taikomojikalbotyra/lt/article/view/34595 (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Vicol, M. I., Gavriluț, M. L., & Mâță, L. (2024). A quasi-experimental study on the development of creative writing skills in primary school students. Education Sciences, 14(1), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemsen, R. H., Schoevers, E. M., & Kroesbergen, E. H. (2020). The structure of creativity in primary education: An empirical confirmation of the amusement park theory. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(4), 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žydžiūnaitė, V. (2018). Implementing ethical principles in social research: Challenges, possibilities and limitations. Profesinis Rengimas: Tyrimai ir Realijos, 29(1), 19–43. [Google Scholar]

| Levels Area of Achievement | Threshold | Satisfactory | Basic | Higher |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability to create a narrative in writing | Writes at least one part of the text according to the requirements of the task, the text is short, and the topic is often not developed. Uses simple, limited vocabulary; sentences may be incoherent or incomplete. Makes 10–12 mistakes from cases that have already been taught. | Creates a text or at least one part of it that meets the requirements of the task. Creates a title for the text that corresponds to the topic, but the topic is not developed. There may be leaps in thought, simple vocabulary and phrases are used, there are no sentence boundaries, and they are incoherent. Makes 6–9 mistakes from the cases they learned. | Creates text according to the structure of the narrative: beginning of the event, development of the event, end of the event. Creates text that corresponds to the topic. Presents events concisely and coherently, but there may be some shortcomings. Sentences and paragraphs are connected; the text is coherent. Various types of sentences are used, the vocabulary is more complex and richer, but there may be some repetitions. 3–5 errors from the cases studied. | The narrative is relevant to the topic and coherent. The text is consistent and logical, with dialogue inserted where appropriate. Sentences are well-developed and use figurative language. There may be 1–3 random spelling or punctuation errors. |

| Questions for Students | Background to the Questions |

|---|---|

| How did you feel while doing this task? | The aim here is to observe how students feel when creating a text with the help of a supplementary aid, and what thoughts and emotions arise. The aim is to find out how the respondents feel (Rupšienė, 2007). |

| How did you do with the task? Why? | These questions are intended to encourage participants to reflect on the entire creative process and what they did while performing the tasks (Rupšienė, 2007). |

| What challenges did you face while writing the text? | The aim of this question is to find out what difficulties students encounter when writing creative works, even when using cheat sheets. The aim is to anticipate changes for future activities and ways to improve the tool. Questions of this type allow for an analysis of the participant’s relationship with the place and environment (Bryman, 2008). |

| How did the cheat sheet help you while writing the text? | These questions aim to find out what the research participant thinks about the research question, to note the suitability of the tool and its use during creative writing (Rupšienė, 2007). The question helps to stay focused on the research goal and keep it at the centre of the interview (Gaižauskaitė & Valavičienė, 2016). |

| How could you improve your text if you were to write it again? | The question aims to find out whether students have noticed the help provided by the cheat sheets and would like to include even more elements in their text. |

| Research Participants | Elements of Figurative Language | Punctuation Mistakes | Common Grammar Mistakes | Connecting Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ugnė | Comparison (triušis buvo pūkuotas, kaip šuo su kailiu [the rabbit was fluffy, like a dog with fur]). There is a lack of synonyms (character names are repeated many times). | No errors were found. | Includes dialogue between characters (Jis pasakė: „Ar tu gali man padėti?” [He said, “Can you help me?”]) | Kartą, staiga [Once, suddenly] |

| Mantas | None. | Separation of conjunctions. | Spelling of nouns in the Galininkas case, spelling of adverb endings. | Kartą, tada [Once, then] |

| Vincentas | None. | Punctuation in direct and interrogative sentences, punctuation of conjunctions. | Spelling of nouns in the Galininkas case, capitalization of sentences. | Tada, kartą [Then, once] |

| Ona | Application of synonyms (vaikų vardai, vaikai, jis, ji, mergaitė, žmonės [children’s names, children, he, she, girl, people]) | Separation of conjunctions. | Spelling of the galininkas and kilmininkas cases of nouns. | Kartą, tada, galiausiai [Once, then, finally] |

| Saulius | None. | Separation of conjunctions. | Spelling at the beginning of a sentence, spelling of the galininkas and kilmininkas cases of nouns, spelling of present tense verb endings. | Kartą [Once] |

| Monika | None. | Separation of conjunctions, punctuation of exclamatory, interrogative, and direct sentences. | Spelling at the beginning of a sentence, spelling of present tense verb endings. | Kartą, staiga, tada [Once, suddenly, then] |

| Ugnė | None. | Separation of conjunctions. | No errors were found. | Vėliau, tada [Later, then] |

| Arnas | None. | Separation of conjunctions. | No errors were found. | Kartą, po dešimties minučių [Once, after ten minutes] |

| Lukas | Diminutives (spynelė [small locket]). Comparison (Tas kambarys buvo be išėjimo, bet su labai daug knygų kaip bibliotekoje [That room had no exit, but it had a lot of books, like a library]). | No errors were found. | No errors were found. | Kartą, pasirodo [Once, it turns out] |

| Justas | None. | Separation of conjunctions (bet, nes, o, kad [but, because, oh, that]). | Spelling of nouns in the Galininkas case. Spelling of present tense verb endings. | Kartą, pirma, paskui, tada [Once, first, then] |

| Miglė | None. | Separation of conjunctions (bet [but]). | Spelling of nouns in the Galininkas case. Spelling of prefixes (yšokome [yšokome]). Memorable spelling words (negryžo, negryš [did not return, will not return]). | Kartą, tada, paskui [Once, then, afterwards] |

| Austėja | None. | Separation of conjunctions (kad [that]). | Spelling of adverb endings. Spelling of nouns in the Galininkas case. | Kartą [Once] |

| Ignas | None. | No errors were found. | Spelling of nouns in the Galininkas case. | Kartą, tada [Once, then] |

| Saulė | None. | Separation of conjunctions, punctuation of exclamatory, interrogative, and direct sentences. | Spelling of adverb endings Spelling of noun endings in the Galininkas, Kilmininkas and Vietininkas cases. Spelling of present tense verb endings. | Vieną kartą [One upon a time] |

| Research Participants | A collection of Figurative Language and/or Proverbs Used | Punctuation Mnemonics Used in the Sentence | Applied Spelling Mnemonics | Applied Sentence Openings Mnemonics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ugnė | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | + | + | - |

| Mantas | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | - | - | - |

| Vincentas | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | Commas were used to delimit the conjunctions. | Sentences began to be written with a capital letter. Corrected the endings of the Galininkas case of the noun. Correct spelling of nasal letters. | Po kelių akimirkų… [A few moments later…] |

| Ona | Comparison (buvo tamsu lyg į akį durk [it was dark as pitch]), antonyms (pasirodė ne tamsi, o spalvota gėlė [appeared not dark, but colorful flower]), phraseological expression (užmetėme akį, mums širdis į kulnus nusirito [we took a look, our hearts sank]). | Commas were used to delimit the conjunctions. | Corrected the endings of the Galininkas case of the noun. | Staigiai… Vėliau… Netikėtai… [Suddenly… Later… Unexpectedly…] |

| Saulius | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | Commas were used to delimit the conjunctions. | Sentences written correctly. Corrected the endings of the Galininkas case of the noun. | - |

| Monika | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | Appropriate punctuation was used to distinguish direct, exclamatory, and interrogative sentences. | Failed to notice and correct spelling and punctuation errors. | - |

| Ugnė | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | Commas were used to delimit the conjunctions. | + | Vieną kartą… Vėliau… Staiga… Galiausiai… [Once… Later… Suddenly… Finally…] |

| Arnas | Diminutive (raktelis [small key]). | Commas were used to delimit the conjunctions. | + | - |

| Lukas | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | + | + | Kitą kartą… Staiga… [Next time… Suddenly…] |

| Justas | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | Commas were used to delimit the conjunctions. | Spelling of present tense endings of verbs (apsirengėme, atsisveikinome, išsigandome [We got dressed, said goodbye, and got scared]). Corrected the endings of the Galininkas case of the noun. | Staiga… Pirmiausia… Vieną kartą… [Suddenly… First of all… Once…] |

| Miglė | Proverb (žmogus be draugų yra, kaip medis be šakų [A person without friends is like a tree without branches]). | - | Correctly spelled memorable words and nouns in the Galininkas case. | Vieną kartą… Vėliau… Galiausiai… [Once… Later… Finally…] |

| Austėja | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | - | Correctly spelled nouns in the Galininkas case. | - |

| Ignas | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | + | Corrected the endings of the Galininkas case of the noun. | Vieną kartą… Galiausiai… [Once… Finally…] |

| Saulė | The mnemonic could not be utilized by the participant in a manner consistent with his/her cognitive abilities. | Punctuation mistakes remained uncorrected. | Not all mistakes were noticed and corrected. Only a few cases of spelling errors in the Galininkas case of nouns were corrected. | - |

| Research Participants | A Collection of Figurative Language and/or Proverbs Used | Punctuation Mnemonics Used in the Sentence | Applied Spelling Mnemonics | Applied Sentence Openings Mnemonics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ugnė | The participant did not possess this memory aid. | + | Spelling of nouns in the Galininkas case (not all cases were successfully corrected). | Po kiek laiko… [After some time…] |

| Mantas | The participant did not possess this memory aid. | Errors were corrected with the support of the teacher and the use of mnemonics. | Errors were corrected with the support of the teacher and the use of mnemonics. | Vieną pavasario dieną, vėliau, po kurio laiko, tuo metu, netikėtai, galiausiai… [One spring day, later, after some time, at that moment, unexpectedly, finally…] |

| Vincentas | The participant did not possess this memory aid. | Errors were corrected with the support of the teacher and the use of mnemonics. | Errors were corrected with the support of the teacher and the use of mnemonics. | Vieną niūrų žiemos rytą, vėliau, po kelių akimirkų, po dvidešimt keturių valandų… [One gloomy winter morning, later, after a few moments, after twenty-four hours…] |

| Ona | Phraseology (idiom) (net širdis į kulnus nusirito, iš laimės širdis spurdėjo [even my heart skipped a beat, my heart was pounding with happiness]). | + | The errors were successfully corrected. | - |

| Saulius | The participant did not possess this memory aid. | The spelling of the Galininkas case endings of nouns has been corrected. | Seniai, seniai, tada… [Long, long ago, then…] | |

| Monika | Synonym for the word matė—regėjusi [saw—has seen]. Deminutyvai (mergytės [little girls]). | The errors were successfully corrected. | The errors were successfully corrected. | Po kelių minučių… [After a few minutes…] |

| Ugnė | The participant did not possess this memory aid. | + | + | Buvo vasara, dabar, staiga, po trijų mėnesių… [It was summer, and now, suddenly, after three months…] |

| Arnas | Proverb (už pinigus negalima nusipirkti draugo [You can’t buy a friend with money]). Comparison (raudonas, kaip burokas, greitas, kaip vėjas, lengvas, kaip plunksna [red as a beet, fast as the wind, light as a feather]). Phraseology (idiom) (širdis į kulnus nusirito, širdis iš džiaugsmo šokinėjo [my heart sank, my heart leapt with joy]). | + | Changed the numerals and wrote them correctly. | Išaušo ilgai laukta diena, tą dieną… [The long-awaited day dawned, that day…] |

| Lukas | The participant did not possess this memory aid. | + | + | - |

| Justas | The participant did not possess this memory aid. | The errors were successfully corrected. | + | Kartą, vieną kartą, tada, vieną rudens dieną… [Once, just once, then, one autumn day…] |

| Kaja | Phraseology (idiom) (širdis iš džiaugsmo šokinėjo [my heart sank, my heart leapt with joy]). | + | + | - |

| Austėja | The participant did not possess this memory aid. | - | + | - |

| Ignas | Metaphor (kojos nukrito [legs fell off]). | - | The errors were successfully corrected. | Vieną kartą [Once upon a time] |

| Saulė | The participant did not possess this memory aid. | Errors were corrected with the support of the teacher and the use of mnemonics. | Errors were corrected with the support of the teacher and the use of mnemonics. | Vieną pavasario dieną, staiga, paskui, tada, vėliau… [One spring day, suddenly, then, later…] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė, D.; Šarūnaitė, G. Creating Written Stories for Primary School Students Based on Personalized Mnemonics: The Case of One Lithuanian School. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010063

Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė D, Šarūnaitė G. Creating Written Stories for Primary School Students Based on Personalized Mnemonics: The Case of One Lithuanian School. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleJakavonytė-Staškuvienė, Daiva, and Gabija Šarūnaitė. 2026. "Creating Written Stories for Primary School Students Based on Personalized Mnemonics: The Case of One Lithuanian School" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010063

APA StyleJakavonytė-Staškuvienė, D., & Šarūnaitė, G. (2026). Creating Written Stories for Primary School Students Based on Personalized Mnemonics: The Case of One Lithuanian School. Education Sciences, 16(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010063