Reconceptualizing Quality Teaching: Insights Based on a Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Context and Implications

2. Literature Review

2.1. Quality Teaching

2.2. Components of QT Adapted to the Framework of Education 4.0

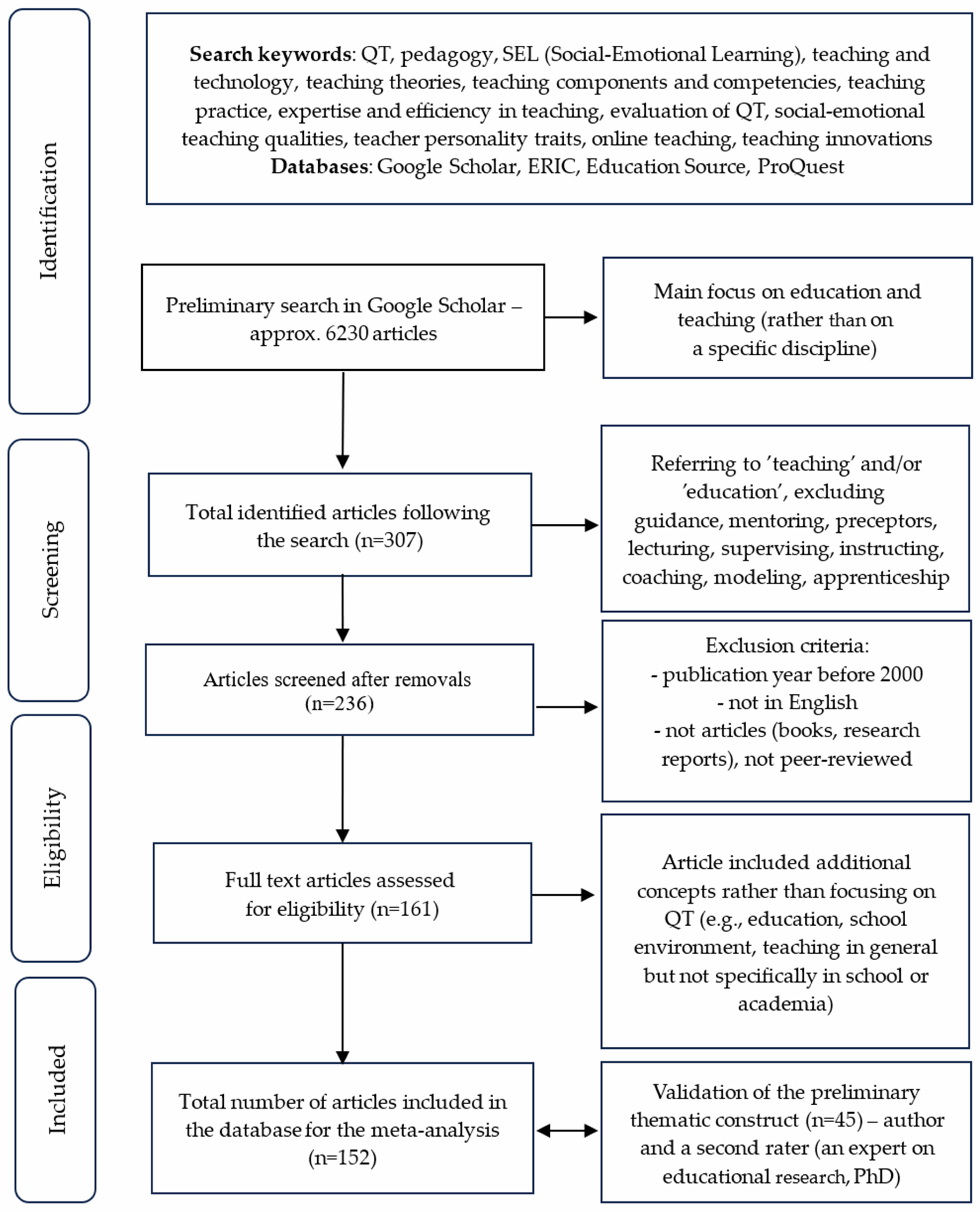

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Review Approach

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.3. Distribution of Articles by Domain

3.4. Coding the Study’s Characteristics

3.5. Research Approach

3.6. Thematic Analysis

4. Results

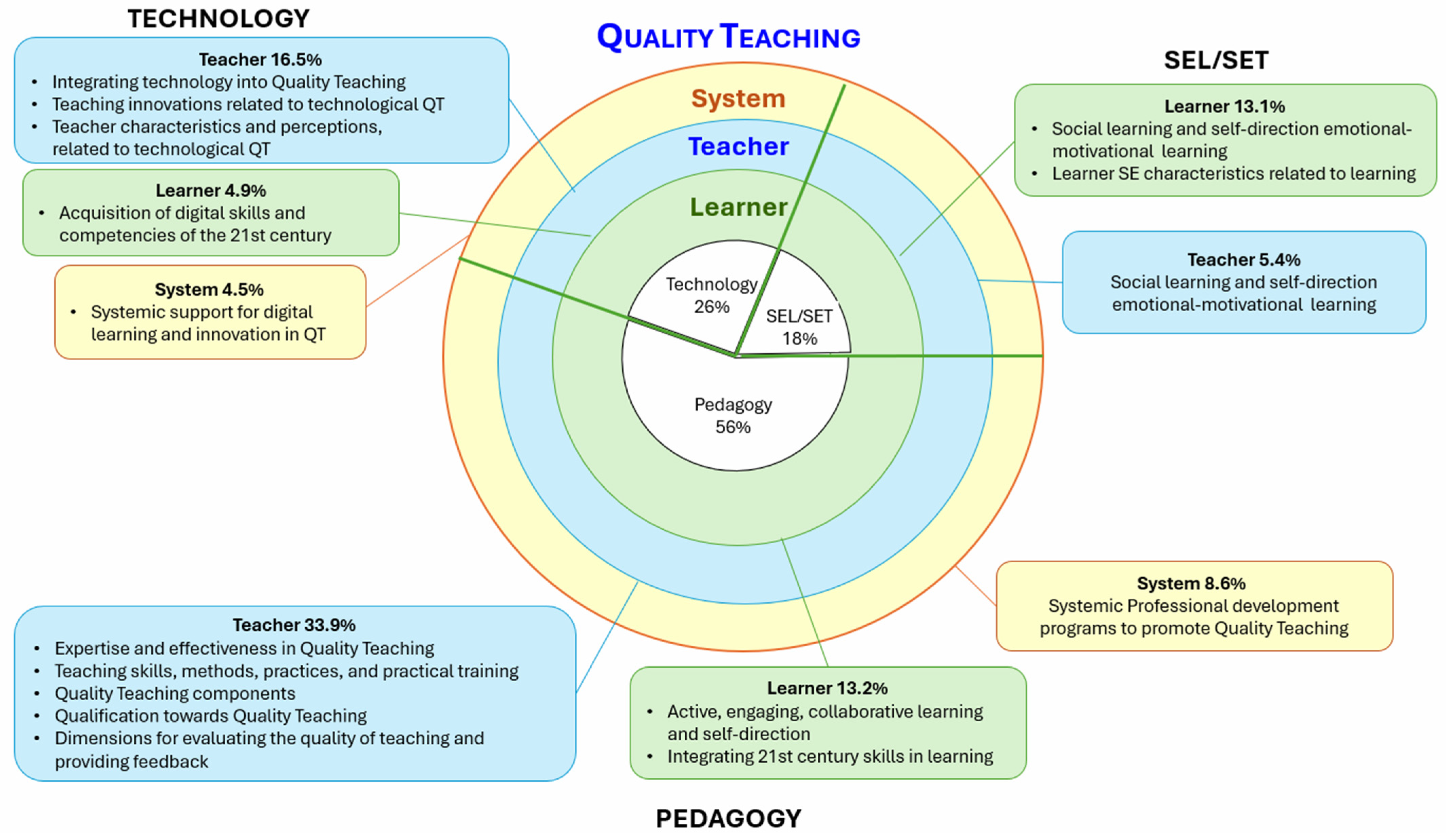

4.1. Distribution of QT

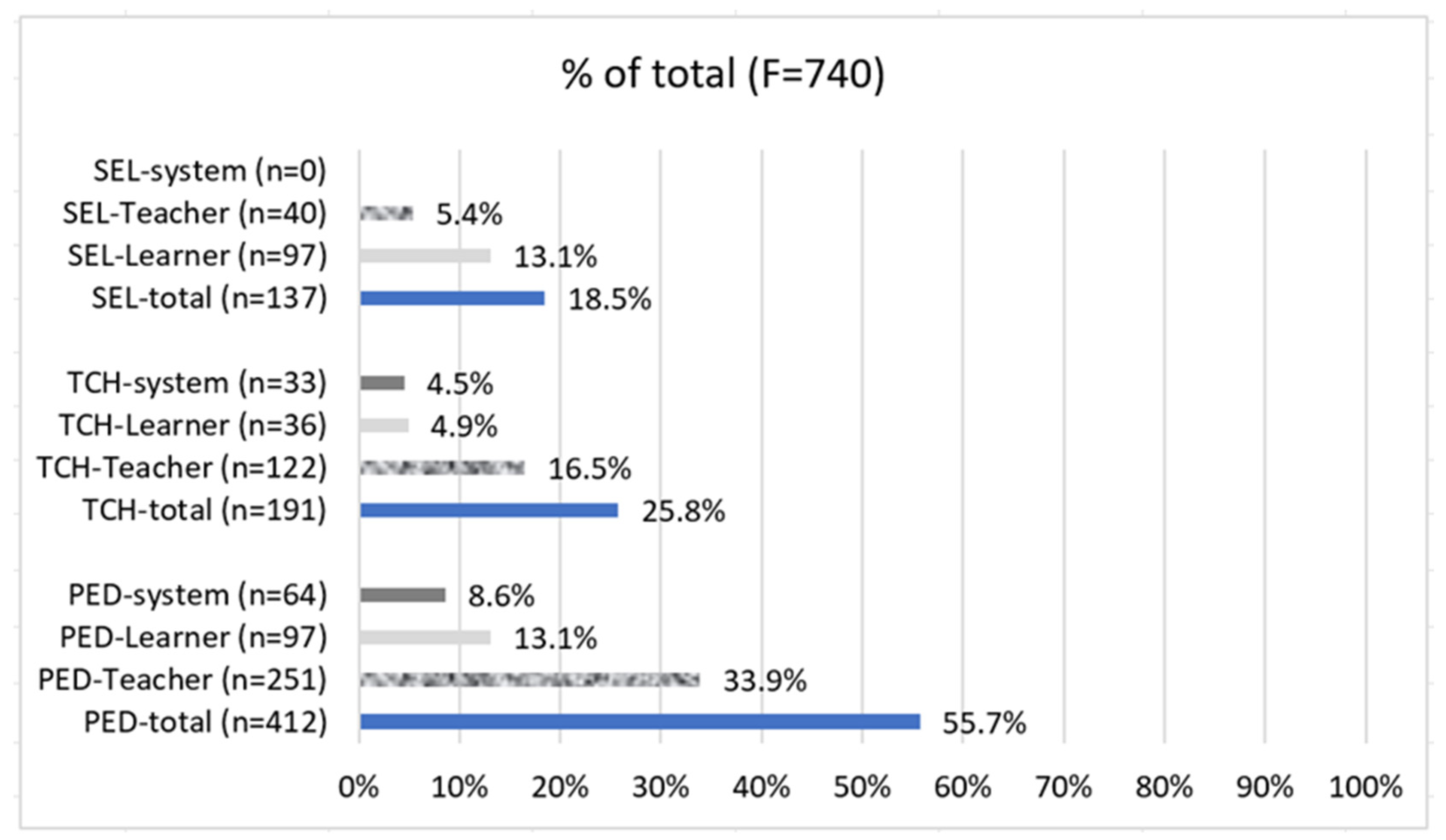

4.2. Characteristics of QT: Distribution of 740 Themes Related to QT by Focus

4.2.1. Pedagogy

- (a)

- Pedagogy: Teacher (f = 251, 33.9% of Total)

- (b) Pedagogy: Learner (f = 97, 13.1% of Total)

- (c) Pedagogy: System (f = 64, 8.6% of Total)

4.2.2. Technology—ICT

- (a)

- Technology: Teacher (f = 122, 16.5% of Total)

- (b) Technology: Learner (f = 36, 4.9% of total)

- (c) Technology: System (f = 33, 4.5% of Total)

4.2.3. SEL/SET

- (a)

- SEL/SET: Learner (f = 97, 13.1% of Total)

- (b) SEL/SET: Teacher (f = 40, 5.4% of total)

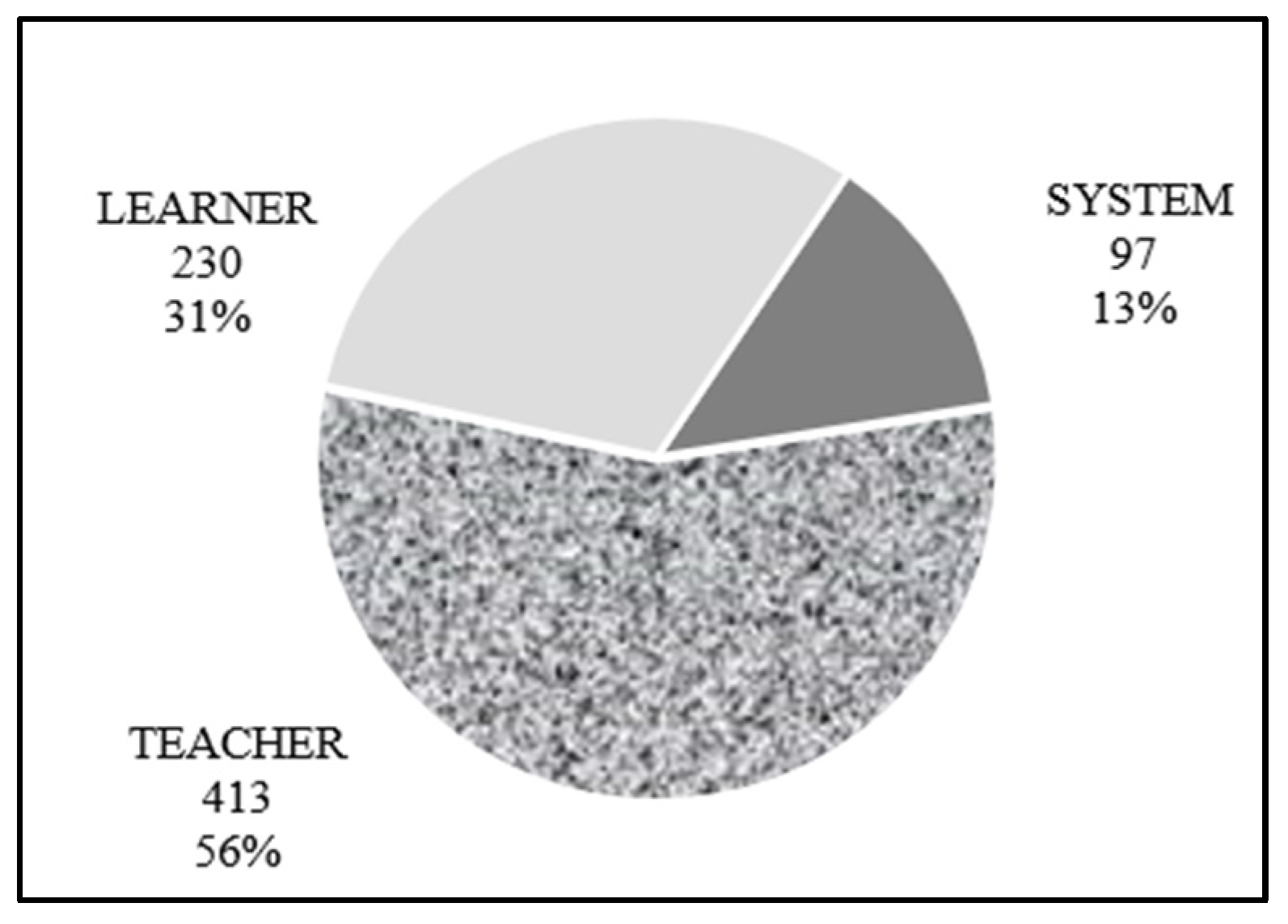

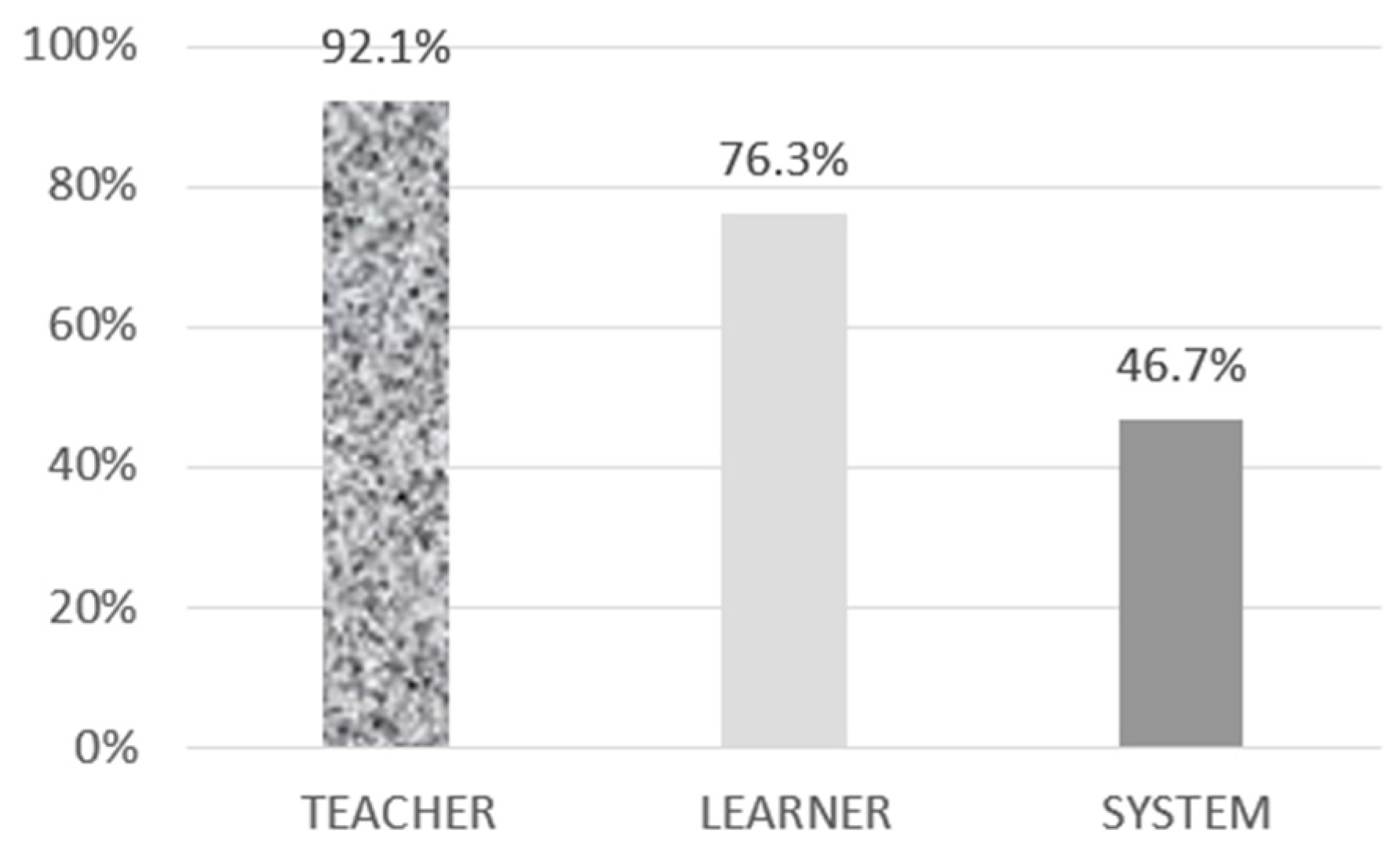

4.2.4. Summary of Findings According to the Focuses of the Articles

4.3. Summary of the Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. General Discussion of the Results

5.2. Practical Implications

- Offering role models of effective practice that demonstrate desired skills promoting QT. These role models may serve as educational change agents who support continuous professional development.

- Explicitly explaining the rationale underlying selected instructional practices and presenting them as problem-solving strategies.

- Developing classroom management practices and techniques through role-playing activities.

- Scaffolding authentic technology-based experiences to enhance teachers’ familiarity and confidence with educational technologies.

- Encouraging continuous reflection on the role of technology in teaching and learning.

- Facilitating active discussions addressing teachers’ perceptions and attitudes toward technology integration (including AI), rather than focusing solely on technical or operational aspects.

- Reducing professional isolation by providing diverse forms of support, such as modeling, coaching, and expert guidance.

- Incorporating active learning approaches that emphasize instructional methods, didactics, and pedagogical strategies.

- Integrating authentic tasks and activities that reflect real-world classroom situations.

- Defining SEL/SET skills as an integral component of the teacher’s professional role, with particular emphasis on emotion regulation, empathy, interpersonal communication, and conflict management.

- Promoting group discussions focused on real-life classroom cases, enabling teachers to reflect on challenges, anticipate potential difficulties, and effectively cope with unexpected situations.

- Initiating and supporting peer collaboration and professional interaction among teachers, with particular attention to social–emotional dimensions, including through engagement in online professional learning communities.

5.3. Research Limitations

- QT is researched across various disciplines (e.g., medicine and social science) beyond merely education/teaching studies.

- Many of the articles were related to multiple fields of study, requiring careful subjective judgment on disciplinary association.

- The results illustrate general, non-subject-specific characteristics of QT. On the one hand, this may allow for generalization, but on the other hand, some of the conclusions may be effective only for teachers in the reviewed educational systems, including higher education.

- The SEL/SET domain varies according to students’ ages (grade levels), and therefore generalization regarding this domain should take age differences into account.

5.4. Recommendations for Further Research

5.5. Summary

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Using the term “themes” in this context refers to the “quotes” from each article (i.e., “units of meaning”), which have a common “focus” and a common “domain”. We could have used the term “quotes” instead, but we assumed that this rather technical term overlooks the contextual reference that the term “theme” bears. |

References

- Agbo, F. J., Olaleye, S. A., Bower, M., & Oyelere, S. S. (2023). Examining the relationships between students’ perceptions of technology, pedagogy, and cognition: The case of immersive virtual reality mini games to foster computational thinking in higher education. Smart Learning Environments, 10(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A. S., Dănăiaţă, D., & Gavrilă, A. (2022). The role of school managers in the process of using technological means in the learning process during COVID-19 crisis. Revista de Management Comparat International, 23(1), 122–135. Available online: https://www.rmci.ase.ro/no23vol1/09.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Albion, P. R., & Tondeur, J. (2018). Information and communication technology and education: Meaningful change through teacher agency. In J. Voogt, G. Knezek, R. Christensen, & K. W. Lai (Eds.), Second handbook of information technology in primary and secondary education (pp. 381–396). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W. (2019). The efficacy of evolving technology in conceptualizing pedagogy and practice in higher education. Higher Education Studies, 9(2), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amedu, J., & Hollebrands, K. F. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of using technology to teach mathematics during COVID-19 remote learning. REDIMAT, 11(1), 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J., & Taner, G. (2023). Building the expert teacher prototype: A metasummary of teacher expertise studies in primary and secondary education. Educational Research Review, 38, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anosova, A., Horpynchenko, O., Bulavina, O., Shevchuk, H., & Valentieva, T. (2022). The use of active learning methods for lifelong education. Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, 13(3), 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arega, N. T., & Hunde, T. S. (2025). Constructivist instructional approaches: A systematic review of evaluation-based evidence for effectiveness. Review of Education, 13(1), e70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artino, A. R. (2008). Motivational beliefs and perceptions of instructional quality: Predicting satisfaction with online training. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 24, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadi, N., Murad, T., & Khalil, M. (2019). Training teachers’ perspectives of the effectiveness of the “Academy-Class” training model on trainees’ professional development. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 9(2), 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, S., Schellings, G. L., Joore, J. P., & van Wesemael, P. J. (2023). Physical learning environments’ supportiveness to innovative pedagogies: Students’ and teachers’ experiences. Learning Environments Research, 26(2), 617–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D. L. (2000). Bridging practices: Intertwining content and pedagogy in teaching and learning to teach. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efcacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, M., & Mourshed, M. (2007). How the world’s best performing school systems come out on top. McKinsey and Company. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/public%20and%20social%20sector/our%20insights/how%20the%20worlds%20best%20performing%20school%20systems%20come%20out%20on%20top/how_the_world_s_best-performing_school_systems_come_out_on_top.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Bastian, K. C., Patterson, K. M., & Carpenter, D. (2022). Placed for success: Which teachers benefit from high-quality student teaching placements? Educational Policy, 36(7), 1583–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidjerano, T., & Dai, D. Y. (2007). The relationship between the big-five model of personality and self-regulated learning strategies. Learning and Individual Differences, 17(1), 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierman, K. L., & Sanders, M. T. (2021). Teaching explicit social-emotional skills with contextual supports for students with intensive intervention needs. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 29(1), 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlsma, H. J., Glas, C. A., & Visscher, A. J. (2022). Factors related to differences in digitally measured student perceptions of teaching quality. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 33(3), 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. W., Killingsworth, K., & Alavosius, M. P. (2014). Interteaching: An evidence-based approach to instruction. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 26(1), 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bruso, J., Stefaniak, J., & Bol, L. (2020). An examination of personality traits as a predictor of the use of self-regulated learning strategies and considerations for online instruction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68, 2659–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A. S., & Fedorek, B. (2017). Does “flipping” promote engagement? A comparison of a traditional, online, and flipped class. Active Learning in Higher Education, 18(1), 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J., Wen, Q., Qi, Z., & Lombaerts, K. (2023). Identifying core features and barriers in the actualization of growth mindset pedagogy in classrooms. Social Psychology of Education, 26(2), 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z., Gui, Y., Mao, P., Wang, Z., Hao, X., Fan, X., & Tai, R. H. (2023). The effect of feedback on academic achievement in technology-rich learning environments (TREs): A meta-analytic review. Educational Research Review, 39, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E., Hategeka, K. B., & Singal, N. (2024). Head teacher and government officials’ perceptions of teaching quality in secondary education in Rwanda. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 52(6), 1455–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A. A., Antonietti, C., & Rauseo, M. (2022). How digitalised are vocational teachers? Assessing digital competence in vocational education and looking at its underlying factors. Computers & Education, 176, 104358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. K. Y., & Lee, K. K. (2023). The AI generation gap: Are Gen Z students more interested in adopting generative AI such as ChatGPT in teaching and learning than their Gen X and millennial generation teachers? Smart Learning Environments, 10(1), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, M. A., & Kazim, E. (2022). Artificial intelligence in education (AIED): A high-level academic and industry note 2021. AI and Ethics, 2(1), 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. H., Chen, K. Z., & Tsai, H. F. (2022). Did self-directed learning curriculum guidelines change Taiwanese high-school students’ self-directed learning readiness? The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 31(4), 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherng, H. Y. S., Halpin, P. F., & Rodriguez, L. A. (2022). Teaching bias? Relations between teaching quality and classroom demographic composition. American Journal of Education, 128(2), 171–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshenko, O. S., Kankaraš, M., & Drasgow, F. (2018). Social and emotional skills for student success and well-being: Conceptual framework for the OECD study on social and emotional skills (OECD Education Working Papers, No. 173). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H., Jung, I., & Lee, Y. (2023). The power of positive deviance behaviours: From panic-gogy to effective pedagogy in online teaching. Education and Information Technologies, 28(10), 12651–12669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2021). Exploring teacher quality: International perspectives. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, C., Murray, C., Brady, B., Mac Ruairc, G., & Dolan, P. (2023). New actors and new learning spaces for new times: A framework for schooling that extends beyond the school. Learning Environments Research, 26(1), 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cress, T., & Kalthoff, H. (2023). Hybrid imbalance: Collaborative fabrication of digital teaching and learning material. Qualitative Sociology, 46, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Sykes, G. (2003). Wanted, a national teacher supply policy for education: The right way to meet the “highly qualified teacher” challenge. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh, L., & Franke, N. (2023). Online mathematics programs and the figured world of primary school mathematics in the digital era. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 35(1), 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pro Chereguini, C., & Ponce Gea, A. I. (2021). Model for the evaluation of teaching competences in teaching–learning situations. Societies, 11(2), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (2012). Human nature and conduct: An introduction to social psychology. Project Gutenberg. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41386/41386-h/41386-h.htm (accessed on 1 March 2022). (Original work published 1922).

- Dicte. (2019). Pedagogical, ethical, attitudinal and technical dimensions of digital competence in teacher education. Developing ICT in Teacher Education Erasmus+ Project. Available online: https://dicte.oslomet.no/dicte/ (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Douglas-Gardner, J., & Callender, C. (2023). Changing teacher educational contexts: Global discourses in teacher education and its effect on teacher education in national contexts. Power and Education, 15(1), 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutse, N., Panishoara, G., & Panishoara, I. O. (2014). The profile of the teaching profession–empirical reflections on the development of the competences of university teachers procedia. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 140, 390–395. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., Baabdullah, A. M., Koohang, A., Raghavan, V., Ahuja, M., Albanna, H., Albashrawi, M. A., Al-Busaidi, A. S., Balakrishnan, J., Barlette, Y., Basu, S., Bose, I., Brooks, L., Buhalis, D., … Wright, R. (2023). “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egara, F. O., & Mosimege, M. (2024). Effect of flipped classroom learning approach on mathematics achievement and interest among secondary school students. Education and Information Technologies, 29(7), 8131–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbach, B., & Coleman, B. (2024). Online pedagogies and the middle grades: A scoping review of the literature. Education Sciences, 14(9), 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, A., & Zlibansky Eden, A. (2019). Adapting the education system to the 21st century. The Israeli Democracy Institute. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- El-Hamamsy, L., Monnier, E. C., Avry, S., Chevalier, M., Bruno, B., Dehler Zufferey, J., & Mondada, F. (2024). Modelling the sustainability of a primary school digital education curricular reform and professional development program. Education and Information Technologies, 29(3), 2857–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterhazy, R., de Lange, T., Bastiansen, S., & Wittek, A. L. (2021). Moving beyond peer review of teaching: A conceptual framework for collegial faculty development. Review of Educational Research, 91(2), 237–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, M. (2023). The effects of microlearning-supported flipped classroom on pre-service teachers’ learning performance, motivation and engagement. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 12687–12714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J., & Everatt, J. (2021). Innovative learning environments in New Zealand: Student teachers’ perceptions. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 56(1), 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortus, D., Lin, J., & Passentin, S. (2023). Shifting from face-to-face instruction to distance learning of science in china and israel during COVID-19: Students’ motivation and teachers’ motivational practices. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 21(7), 2173–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, J., Radianti, J., Wehking, C., Stieglitz, S., Majchrzak, T. A., & vom Brocke, J. (2021). More than experience? On the unique opportunities of virtual reality to afford a holistic experiential learning cycle. The Internet and Higher Education, 50, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, F. F., & Bown, O. H. (1975). Becoming a teacher. Teachers College Record, 76(6), 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, N., & Dubeau, A. (2023). Building and maintaining self-efficacy beliefs: A study of entry-level vocational education and training teachers. Vocations and Learning, 16, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, E., & Curwood, J. S. (2023). A world beyond self: Empathy and pedagogy during times of global crisis. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 46(2), 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayman, C. M., Hammonds, F., & Rost, K. A. (2018). Interteaching in an asynchronous online class. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 4(4), 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgara, A., Kazhamiakin, R., Mich, O., Palmero Approsio, A., Pazzaglia, J. C., Rodríguez Aguilar, J. A., & Sierra, C. (2023). The AI4Citizen pilot: Pipelining AI-based technologies to support school-work alternation programmes. Applied Intelligence, 53, 24157–24186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, L., Bradford, A., & Linn, M. C. (2022). Supporting teachers to customize curriculum for self-directed learning. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 31(5), 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhard, K., Jäger-Biela, D. J., & König, J. (2023). Opportunities to learn, technological pedagogical knowledge, and personal factors of pre-service teachers: Understanding the link between teacher education program characteristics and student teacher learning outcomes in times of digitalization. Zeitschrift fur Erziehungswissenschaft, 26, 653–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, A. F., Sandilos, L. E., Pilny, W. V., Schwartz, S., & Wehby, J. H. (2022). Teaching students with emotional/behavioral disorders: Teachers’ burnout profiles and classroom management. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 30(1), 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbert, B. G., Miller, D., Herman, E., Breedlove, M., & Molina, C. E. (2023). Social emotional learning in schools: The importance of educator competence. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 18(1), 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloppen, S. K. (2023). Enacting teacher evaluation in Norwegian compulsory education: Teachers’ perceptions of possibilities and constraints. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 35(3), 387–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goagoses, N., Suovuo, T., Winschiers-Theophilus, H., Suero Montero, C., Pope, N., Rötkönen, E., & Sutinen, E. (2024). A systematic review of social classroom climate in online and technology-enhanced learning environments in primary and secondary school. Education and Information Technologies, 29(2), 2009–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomis, K., Saini, M., Pathirage, C., & Arif, M. (2022). Enhancing quality of teaching in the built environment higher education, UK. Quality Assurance in Education, 30(4), 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, L. I., & Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. (2022). Components of Education 4.0 in 21st century skills frameworks: Systematic review. Sustainability, 14(3), 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, J., Rosser, B., Jaremus, F., Miller, A., & Harris, J. (2024). Fresh evidence on the relationship between years of experience and teaching quality. The Australian Educational Researcher, 51(2), 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, K. L., Sutherland, K. S., Conroy, M. A., Dear, E., & Morse, A. (2023). Teacher burnout and supporting teachers of students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 31(2), 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Großmann, L., & Krüger, D. (2024). Assessing the quality of science teachers’ lesson plans: Evaluation and application of a novel instrument. Science Education, 108(1), 153–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X., Zhu, Y., & Guo, X. (2013). Meeting the “digital natives”: Understanding the acceptance of technology in classrooms. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 16(1), 392–402. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.16.1.392 (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Han, X., Ge, W., Wang, S., Wang, S., & Zhou, Q. (2024). Standards framework and evaluation instruments. In J. Cheng, W. Han, Q. Zhou, & S. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of teaching competency development in higher education (pp. 37–62). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, D. M., Gudmundsdottir, G. B., & Korona, M. (2024). Teachers’ online preparedness in times of crises: Trends from Norway and US. Education and Information Technologies, 29(2), 1489–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazzan-Bishara, A., Kol, O., & Levy, S. (2025). The factors affecting teachers’ adoption of AI technologies: A unified model of external and internal determinants. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 15043–15069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemi, M. E., & Kasperski, R. (2023). Development and validation of ‘Edusel’: Educators’ socio-emotional learning questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 201, 111926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-de-Menendez, M., Escobar Díaz, C. A., & Morales-Menendez, R. (2020). Educational experiences with generation Z. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing, 14, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershkovitz, A., Daniel, E., Klein, Y., & Shacham, M. (2023). Technology integration in emergency remote teaching: Teachers’ self-efficacy and sense of success. Education and Information Technologies, 28(10), 12433–12464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, B., Grainger Clemson, H., Tasic Hansen, D., Laurillard, D., Murray, M., Fernandes, L., Gilleran, A., Ruiz, D. R., & Rutkauskiene, D. (2022). A pedagogical model for effective online teacher professional development—Findings from the Teacher Academy initiative of the European Commission. European Journal of Education, 57(1), 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, T., Lundin, M., Rensfeldt, A. B., Lantz-Andersson, A., & Peterson, L. (2021). Moderating professional learning on social media-A balance between monitoring, facilitation and expert membership. Computers & Education, 168, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, L. M. A., & Koifman, L. (2013). The supervising look in the perspective of changing processes activation. Physis, 23(2), 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W., Porayska-Pomsta, K., Holstein, K., Sutherland, E., Baker, T., Shum, S. B., Santos, O. C., Rodrigo, M. T., Cukurova, M., Ibert Bittencourt, I., & Koedinger, K. R. (2021). Ethics of AI in education: Towards a community-wide framework. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 32, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, J. E. S., & Schweig, J. D. (2022). SEL in context: School mobility and social-emotional learning trajectories in a low-income, urban school district. Education and Urban Society, 56(2), 164–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyert, M., & O’Dell, C. (2019). Developing faculty communities of practice to expand the use of effective pedagogical techniques. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 19(1), 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, F. P., Lin, H. S., Liu, S. C., & Tsai, C. Y. (2021). Effect of peer coaching on teachers’ practice and their students’ scientific competencies. Research in Science Education, 51, 1569–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Huang, R., & Trouche, L. (2023). Teachers’ learning from addressing the challenges of online teaching in a time of pandemic: A case in Shanghai. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 112(1), 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-Parrado, C., Pfaller-Sadovsky, N., Medina, L., Gayman, C. M., Rost, K. R., & Schofill, D. (2021). A systematic review and quantitative analysis of interteaching. Journal of Behavioral Education, 31, 157–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichsan, I., Suharyat, Y., Santosa, T. A., & Satria, E. (2023). The effectiveness of stem-based learning in teaching 21 st century skills in generation z student in science learning: A meta-analysis. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA, 9(1), 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenßen, L., Eilerts, K., & Grave-Gierlinger, F. (2023). Comparison of pre-and in-service primary teachers’ dispositions towards the use of ICT. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 14857–14876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrim, J., Sims, S., & Oliver, M. (2023). Teacher self-efficacy and pupil achievement: Much ado about nothing? International evidence from TIMSS. Teachers and Teaching, 29(2), 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocius, R., O’Byrne, W. I., Albert, J., Joshi, D., Blanton, M., Robinson, R., Andrews, A., Barnes, T., & Catete, V. (2022). Building a virtual community of practice: Teacher learning for computational thinking infusion. TechTrends, 66, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, M. S. Y. (2023). Flipped classroom: Motivational affordances of spherical video-based immersive virtual reality in support of pre-lecture individual learning in pre-service teacher education. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 35(1), 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jõgi, L., Karu, K., & Krabi, K. (2015). Rethinking teaching and teaching practice at university in a lifelong learning context. International Review of Education, 61, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, G., Blömeke, S., König, J., Busse, A., Döhrmann, M., & Hoth, J. (2017). Professional competencies of (prospective) mathematics teachers—Cognitive versus situated approaches. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 94, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A., & Maehr, M. L. (2007). The contributions and prospects of goal orientation theory. Educational Psychology Review, 19(2), 141–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca-Atik, A., Meeuwisse, M., Gorgievski, M., & Smeets, G. (2023). Uncovering important 21st -century skills for sustainable career development of social sciences graduates: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 39, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E., Seßler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemanna, S., Hüllermeier, E., Krusche, S., Kutyniok, G., Michaeli, T., Nerdel, C., Pfeffer, J., Poquet, O., Sailer, M., Schmidt, A., Seidel, T., … Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, H., Celik, I., Le, T. T., Lai, V. T. T., Nguyen, A., & Bui, H. (2022). Examining teachers’ behavioural intention for online teaching after COVID-19 pandemic: A large-scale survey. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 5999–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, H., Shum, S. B., Chen, G., Conati, C., Tsai, Y. S., Kay, J., Knight, S., Martinez-Maldonado, R., Sadiq, S., & Gašević, D. (2022). Explainable artificial intelligence in education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L. E., Jörg, V., & Klassen, R. M. A. (2019). Meta-analysis of the effects of teacher personality on teacher effectiveness and burnout. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L., Moorhouse, B. L., & Zou, D. (2023). ChatGPT for language teaching and learning. RELC Journal, 54(2), 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonté, C., & Smith, V. R. (2022). Learning through technology in middle school classrooms: Students’ perceptions of their self-directed and collaborative learning with and without technology. Education and Information Technologies, 27(5), 6317–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C., & Jin, T. (2021). Teacher professional identity and the nature of technology integration. Computers & Education, 175, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird-Gentle, A., Larkin, K., Kanasa, H., & Grootenboer, P. (2023). Systematic quantitative literature review of the dialogic pedagogy literature. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 46(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, M., Boerst, T., & Graziani, F. (2011). Organizational resources in the service of school-wide ambitious teaching practice. Teachers College Record, 113(7), 1361–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. L., & Johnes, J. (2022). Using network DEA to inform policy: The case of the teaching quality of higher education in England. Higher Education Quarterly, 76(2), 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. H., & Gargroetzi, E. (2023). “It’s like a double-edged sword”: Mentor perspectives on ethics and responsibility in a learning analytics–supported virtual mentoring program. Journal of Learning Analytics, 10(1), 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer-Knafo, O. (2019). How to improve the quality of teaching in higher education? The application of the feedback conversation for the effectiveness of interpersonal communication. Edukacja, 2, 31–41. Available online: http://polona.pl/item/127871010 (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Li, M., & Li, B. (2024). Unravelling the dynamics of technology integration in mathematics education: A structural equation modelling analysis of TPACK components. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 23687–23715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenberg Ball, D., & Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(5), 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckin, R., Cukurova, M., Kent, C., & du Boulay, B. (2022). Empowering educators to be AI-ready. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100076. [Google Scholar]

- Magro, S. W., Nivison, M. D., Englund, M. M., & Roisman, G. I. (2023). The quality of early caregiving and teacher-student relationships in grade school independently predict adolescent academic achievement. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 47(2), 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero Galván, J. J., Negrín Medina, M. Á., Bernárdez-Gómez, A., & Portela Pruaño, A. (2023). The impact of the first millennial teachers on education: Views held by different generations of teachers. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 14805–14826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, C. S., Romero, M. E., Yang, W., & Weigand, T. (2023). A call for equity-focused social-emotional learning. School Psychology Review, 52(5), 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, S., & Attardi, S. M. (2023). Sage or guide? Student perceptions of the role of the instructor in a flipped classroom. Active Learning in Higher Education, 24(1), 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalec, P., & Wilson, J. L. (2022). Truth hidden in plain sight: How social–emotional learning empowers novice teachers’ culturally responsive pedagogy in title i schools. Journal of Education, 202(4), 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mičiulienė, R., & Kovalčikienė, K. (2023). Motivation to become a vocational teacher as a second career: A mixed method study. Vocations and Learning, 16, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadasi, J., & Keikavoosi-Arani, L. (2023). Investigating the factors influencing students’ academic enthusiasm for a shift of paradigm among education managers shaping academic pedagogy. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, S. Y., Rupp, D., & Holzberger, D. (2023). What kind of individual support activities in interventions foster pre-service and beginning teachers’ self-efficacy? A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 40, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A., Cahill, H., & Dadvand, B. (2022). The role of gender, setting and experience in teacher beliefs and intentions in social and emotional learning and respectful relationships education. The Australian Educational Researcher, 49(1), 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, L., & Grazia, V. (2021). Students’ school climate perceptions: Do engagement and burnout matter? Learning Environments Research, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelimarkka, M., Leinonen, T., Durall, E., & Dean, P. (2021). Facebook is not a silver bullet for teachers’ professional development: Anatomy of an eight-year-old social-media community. Computers & Education, 173, 104269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemorin, S., Vlachidis, A., Ayerakwa, H. M., & Andriotis, P. (2023). AI hyped? A horizon scan of discourse on artificial intelligence in education (AIED) and development. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(1), 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J., & Dusenbury, L. (2015). Social and emotional learning (SEL): A framework for academic, social, and emotional success. In K. Bosworth (Ed.), Prevention science in school settings: Complex relationships and processes (pp. 287–306). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGSS Lead States. (2013). Next generation science standards for states, by states. The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nir, A., Ben-David, A., Bogler, R., Inbar, D., & Zohar, A. (2016). School autonomy and 21st century skills in the Israeli educational system: Discrepancies between the declarative and operational levels. International Journal of Educational Management, 30(7), 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obsuth, I., Murray, A. L., Knoll, M., Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. (2023). Teacher-student relationships in childhood as a protective factor against adolescent delinquency up to age 17: A propensity score matching approach. Crime & Delinquency, 69(4), 727–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019). Improving school quality in Norway: The new competence Development model, implementing education policies. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, O. G., Adamu, A., & Daniel, O. (2023). Relation between students’ personality traits and their preferred teaching methods: Students at the university of Ghana and the Huzhou Normal University. Heliyon, 9(1), e13011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottergren, E., & Ampadu, E. (2023). Transition to hybrid teaching of mathematics: Challenges and coping strategies of Swedish teachers. SN Social Sciences, 3(6), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdemir, N., Kılınç, A. Ç., Polatcan, M., Turan, S., & Bellibaş, M. Ş. (2023). Exploring teachers’ instructional practice profiles: Do distributed leadership and teacher collaboration make a difference? Educational Administration Quarterly, 59(2), 255–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, C. I., Georgiou, D., & Pittich, D. (2024). Technology education in primary schools: Addressing teachers’ perceptions, perceived barriers, and needs. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 34(2), 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette-Smith, M., Buckler, H., & Johnson, E. K. (2023). How sociolinguistic factors shape children’s subjective impressions of teacher quality. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 76(3), 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partnership for 21st century skills. (2009). P21 framework definitions. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED519462.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Peled, Y., & Perzon, S. (2022). Systemic model for technology integration in teaching. Education and Information Technologies, 27(2), 2661–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Jorge, D., González-Afonso, M. C., Santos-Álvarez, A. G., Plasencia-Carballo, Z., & Perdomo-López, C. D. L. Á. (2025). The Impact of AI-Driven Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) on Educational Information Management. Information, 16(7), 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, T. M., Souto-Manning, M., Anderson, L., Horn, I., J. Carter Andrews, D., Stillman, J., & Varghese, M. (2019). Making justice peripheral by constructing practice as “core”: How the increasing prominence of core practices challenges teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom assessment scoring system (CLASS) manual, K–3. Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Pow, W. C. J., & Lai, K. H. (2021). Enhancing the quality of student teachers’ reflective teaching practice through building a virtual learning community. Journal of Global Education and Research, 5(1), 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmatullah, A., Hinckle, M., & Wiebe, E. N. (2022). The role of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and habits in differentiating types of K–12 science teachers. Research in Science Education, 53, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G. K. L., & Mokhtar, N. (2023). Dental education in the information age: Teaching dentistry to generation Z learners using an autonomous smart learning environment. In M. B. Garcia, M. V. Lopez Cabrera, & R. P. P. de Almeida (Eds.), Handbook of research on instructional technologies in health education and allied disciplines (pp. 243–264). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Renta-Davids, A.-I., Jiménez-González, J.-M., Fandos-Garrido, M., & González-Soto, Á.-P. (2016). Organisational and training factors affecting academic teacher training outcomes. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(2), 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, I., Kuusisto, E., Tuominen, M., & Tirri, K. (2019). In search of a growth mindset pedagogy: A case study of one teacher’s classroom practices in a Finnish elementary school. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C. D. (2022). A framework for motivating teacher-student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 2061–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L. A., Nguyen, T. D., & Springer, M. G. (2025). Revisiting teaching quality gaps: Urbanicity and disparities in access to high-quality teachers across Tennessee. Urban Education, 60(2), 467–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roofe, C., Maude, K., & Sunder, S. G. (2023). From classroom teacher to teacher educator: Critical insights and experiences of beginning teacher educators from Jamaica, England and United Arab Emirates. Power and Education, 15(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, L., Bourke, T., L’Estrange, L., Lunn lee, J., Ryan, M., Walker, S., & Churchward, P. (2021). How does initial teacher education research frame the challenge of preparing future teachers for student diversity in schools? A systematic review of literature. Review of Educational Research, 91(1), 112–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Viruel, S., Sánchez Rivas, E., & Ruiz Palmero, J. (2025). The role of artificial intelligence in project-based learning: Teacher perceptions and pedagogical implications. Education Sciences, 15(2), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandilos, L. E., Neugebauer, S. R., DiPerna, J. C., Hart, S. C., & Lei, P. (2022). Social–emotional learning for whom? Implications of a universal SEL program and teacher well-being for teachers’ interactions with students. School Mental Health, 15, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J., Figueiredo, A. S., & Vieira, M. (2019). Innovative pedagogical practices in higher education: An integrative literature review. Nurse Education Today, 72, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanusi, I. T., Oyelere, S. S., Vartiainen, H., Suhonen, J., & Tukiainen, M. (2023). A systematic review of teaching and learning machine learning in K-12 education. Education and Information Technologies, 28(5), 5967–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-López, J. M., Grimaldo-Santamaría, R. Ó., Quicios-García, M. P., & Vázquez-Cano, E. (2024). Teaching the use of gamification in elementary school: A case in spanish formal education. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 29(1), 557–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheeler, M. C. (2008). Generalizing effective teaching skills: The missing link in teacher preparation. Journal of Behavioral Education, 17, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, B. B., Swidan, O., Prusak, N., & Palatnik, A. (2021). Collaborative learning in mathematics classrooms: Can teachers understand progress of concurrent collaborating groups? Computers & Education, 165, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweisfurth, M. (2023). Disaster didacticism: Pedagogical interventions and the ‘learning crisis’. International Journal of Educational Development, 96, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seery, C., Andres, A., Moore-Cherry, N., & O’Sullivan, S. (2021). Students as partners in peer mentoring: Expectations, experiences and emotions. Innovative Higher Education, 46(6), 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitzer, H. (2023). More than meets the eye: Uncovering the evolution of the OECD’s institutional priorities in education. Journal of Education Policy, 38(2), 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, H., Majid, F. A., & Ismail, I. S. (2019). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) in teaching 21st century skills in the 21st century classroom. Asian Journal of University Education, 15(3), 24–33. Available online: https://education.uitm.edu.my/ajue/ (accessed on 27 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Short, C. R., Graham, C. R., Holmes, T., Oviatt, L., & Bateman, H. (2021). Preparing teachers to teach in K-12 blended environments: A systematic mapping review of research trends, impact, and themes. TechTrends, 65(6), 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. K., Kiriti, M. K., Singh, H., & Shrivastava, A. (2025). Education AI: Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on education in the digital age. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 16, 1424–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovák, P., & Fitzpatrick, G. (2015). Teaching and developing social and emotional skills with technology. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 22(4), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smakman, M., Vogt, P., & Konijn, E. A. (2021). Moral considerations on social robots in education: A multi-stakeholder perspective. Computers & Education, 174, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. (2021). Educating teachers for the future school-the challenge of bridging between perceptions of quality teaching and policy decisions: Reflections from Norway. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, M. (2021). Educating quality teachers: How teacher quality is understood in the Netherlands and its implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C., Franchi, T., Mathew, G., Kerwan, A., Nicola, M., Griffin, M., Agha, M., & Agha, R. (2021). PRISMA 2020 statement: What’s new and the importance of reporting guidelines. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriyanto, S., Buchori, A., Handayani, A., Nguyen, P. T., & Usman, H. (2020). Implementation multi factor evaluation process (MFEP) decision support system for choosing the best elementary school teacher. International Journal of Control and Automation, 13(2), 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, S., & Ellis, V. (2021). Teaching quality, social mobility and ‘opportunity’ in England: The case of the teaching and leadership innovation fund. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J., & Yang, W. (2023). Unlocking the power of ChatGPT: A framework for applying generative AI in education. ECNU Review of Education, 6(3), 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L., Kangas, M., Ruokamo, H., & Siklander, S. (2023). A systematic literature review of teacher scaffolding in game-based learning in primary education. Educational Research Review, 40, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swars Auslander, S., Bingham, G. E., Tanguay, C. L., & Fuentes, D. S. (2024). Developing elementary mathematics specialists as teacher leaders during a preparation program. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 27(4), 665–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H. (2021). Teaching teachers to use technology through massive open online course: Perspectives of interaction equivalency. Computers & Education, 174, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, T., Houtveen, T., van de Grift, W., & Willemsen, M. (2018). Learning to teach: Effects of classroom observation, assignment of appropriate lesson preparation templates and stage focused feedback. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 58, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekkumru-Kisa, M., Preston, C., Kisa, Z., Oz, E., & Morgan, J. (2021). Assessing instructional quality in science in the era of ambitious reforms: A pilot study. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 58(2), 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C. L., Zolkoski, S. M., & Sass, S. M. (2022). Investigating the psychometric properties of the social-emotional learning scale. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 47(3), 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. J., da Cunha, J., & Santo, J. B. (2022). Changes in character virtues are driven by classroom relationships: A longitudinal study of elementary school children. School Mental Health, 14, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. K., Barab, S. A., & Tuzun, H. (2009). Developing critical implementations of technology-rich innovations: A cross-case study of the implementation of quest Atlantis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 41(2), 125–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonova, E., & Raitskaya, L. (2023). Education 4.0: The concept, skills, and research. Journal of Language and Education, 9(1), 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, R. Q. E., Koh, K. K., Lua, J. K., Wong, R. S. M., Quah, E. L. Y., Panda, A., Ho, C. Y., Lim, N. A., Ong, Y. T., Chua, K. Z. Y., Ng, V. W. W., Wong, S. L. C. H., Yeo, L. Y. X., See, S. Y., Teo, J. J. Y., Renganathan, Y., Chin, A. M. C., & Krishna, L. K. R. (2022). The role of mentoring, supervision, coaching, teaching and instruction on professional identity formation: A systematic scoping review. BMC Medical Education, 22, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J., Aesaert, K., Prestridge, S., & Consuegra, E. (2018). A multilevel analysis of what matters in the training of pre-service teacher’s ICT competencies. Computers & Education, 122, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J., van Braak, J., Siddiq, F., & Scherer, R. (2016). Time for a new approach to prepare future teachers for educational technology use: Its meaning and measurement. Computers & Education, 94, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, K. D. (2020). Defining “Teacher”. Virginia English Journal, 70(1), 6. Available online: https://digitalcommons.bridgewater.edu/vej/vol70/iss1/6 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Tzimiris, S., Nikiforos, S., & Kermanidis, K. L. (2023). Post-pandemic pedagogy: Emergency remote teaching impact on students with functional diversity. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 10285–10328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valtonen, T., Hoang, N., Sointu, E., Naykki, P., Virtanen, A., Poysa-Tarhonen, J., Hakkinen, P., Jarvela, S., Makitalo, K., & Kukkonen, J. (2021). How pre-service teachers perceive their 21st -century skills and dispositions: A longitudinal perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 116, 106643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laar, E., Van Deursen, A. J., Van Dijk, J. A., & De Haan, J. (2017). The relation between 21st -century skills and digital skills: A systematic literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vembye, M. H., Weiss, F., & Hamilton Bhat, B. (2024). The effects of co-teaching and related collaborative models of instruction on student achievement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 94(3), 376–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, M., Kreijns, K., & Evers, A. T. (2022). Transformational leadership, leader–member exchange and school learning climate: Impact on teachers’ innovative behaviour in the Netherlands. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(3), 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestad, L., & Tharaldsen, K. B. (2022). Building social and emotional competencies for coping with academic stress among students in lower secondary school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(5), 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidergor, H. E. (2018). Effectiveness of the multidimensional curriculum model in developing higher-order thinking skills in elementary and secondary students. The Curriculum Journal, 29(1), 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreekamp, M., Gulikers, J. T., Runhaar, P. R., & Den Brok, P. J. (2024). A systematic review to explore how characteristics of pedagogical development programmes in higher education are related to teacher development outcomes. International Journal for Academic Development, 29(4), 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Gong, S., Cao, Y., Lang, Y., & Xu, X. (2022). The effects of affective pedagogical agent in multimedia learning environments: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 28, 100506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, S., & Borromeo Ferri, R. (2023). Promoting pre-service teachers’ professionalism in steam education and education for sustainable development through mathematical modelling activities. ZDM–Mathematics Education, 55, 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieman, C. E. (2019). Expertise in university teaching & the Implications for teaching effectiveness, evaluation & training. Daedalus, 148(4), 47–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, E. B., Ferrer, N. B., Correnti, R. R., Stein, M. K., & Schunn, C. D. (2021). Coaching that supports teachers’ learning to enact ambitious instruction. Instructional Science, 49(6), 877–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullschleger, A., Voros, A., Rechsteiner, B., Rickenbacher, A., & Merki, K. M. (2023). Improving teaching, teamwork, and school organization: Collaboration networks in school teams. Teaching and Teacher Education, 121, 103909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Kaiser, G., König, J., & Blömeke, S. (2018). Measuring Chinese teacher professional competence: Adapting and validating a German framework in China. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(5), 638–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagni, B., Van Ryzin, M., Ianes, D., & Scrimin, S. (2025). Advancing social and emotional skills through tech-supported cooperative learning in primary and middle schools. European Journal of Education, 60(3), e70166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Bao, J., & He, R. (2023). Characteristics of good mathematics teaching in China: Findings from classroom observations. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 21(4), 1177–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus: | Teacher | Learner | System | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles | f | % | f | % | f | % |

| 0 (none) | 12 | 7.9 | 36 | 23.7 | 81 | 53.3 |

| 1 | 23 | 15.1 | 46 | 30.3 | 48 | 31.6 |

| 2 | 34 | 22.4 | 38 | 25.0 | 20 | 13.2 |

| 3 | 37 | 24.3 | 21 | 13.8 | 3 | 2.0 |

| 4 | 27 | 17.8 | 10 | 6.6 | ||

| 5 | 13 | 8.6 | 1 | 0.7 | ||

| 6 | 4 | 2.6 | ||||

| 7 | 2 | 1.3 | ||||

| Median | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Mean | 2.7 | 1.5 | 0.6 | |||

| SD | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.8 | |||

| Domains | Focuses | N | % of Total | % of Domain | Md | Mean | SD | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall total themes | 740 | 100.0% | 5 | 4.9 | 2.4 | 13 | ||

| Pedagogy | Total | 412 | 55.7% | 100.0% | 3 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 8 |

| Teacher | 251 | 33.9% | 60.9% | 2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 5 | |

| Learner | 97 | 13.1% | 23.5% | 0 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 3 | |

| System | 64 | 8.6% | 15.5% | 0 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 2 | |

| Technology | Total | 191 | 25.8% | 100.0% | 0 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 5 |

| Teacher | 122 | 16.5% | 63.9% | 0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 3 | |

| Learner | 36 | 4.9% | 18.8% | 0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| System | 33 | 4.5% | 17.3% | 0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| SEL/SET | Total | 137 | 18.5% | 100.0% | 1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 3 |

| Learner | 97 | 13.1% | 70.8% | 0 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 2 | |

| Teacher | 40 | 5.4% | 29.2% | 0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| System | 0 | |||||||

| Focus | Pedagogy | Theme | F | % of Total (F = 740) | % of Domain (f = 412) | Mean | SD | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher | Total | Pedagogy Teacher | 251 | 33.9% | 60.9% | 1.7 | 1.3 | 5 |

| Expertise | Expertise and effectiveness in Quality Teaching | 73 | 9.9% | 17.7% | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Practice | Teaching skills, methods, practices, and practical training | 70 | 9.5% | 17.0% | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Components | Quality Teaching components | 55 | 7.4% | 13.3% | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Qualification | Qualification towards Quality Teaching | 39 | 5.3% | 9.5% | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| Evaluation | Dimensions for evaluating the quality of teaching and providing feedback | 14 | 1.9% | 3.4% | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 | |

| Learner | Total | Pedagogy Learner | 97 | 13.1% | 23.5% | 0.6 | 0.8 | 3 |

| Collaboration/self-direction | Active, engaging, collaborative learning and self-direction | 69 | 9.4% | 16.8% | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| Integration | Integrating 21st century skills in learning | 28 | 3.8% | 6.8% | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| System | Professional development | Systemic professional development programs to promote Quality Teaching | 64 | 8.6% | 15.5% | 0.4 | 0.6 | 2 |

| Focus | Technology | Theme | F | % of Total (F = 740) | % of Domain (f = 191) | Mean | SD | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher | Total | 122 | 16.5% | 63.9% | 0.8 | 1.0 | 3 | |

| Integration | Integrating technology into Quality Teaching | 62 | 8.4% | 32.5% | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Innovations | Teaching innovations related to Technological Quality Teaching | 35 | 4.7% | 18.3% | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| Characteristics | Teacher characteristics and perceptions related to technological Quality Teaching | 25 | 3.4% | 13.1% | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| Learner | Acquisition | Acquisition of digital skills and competencies of the 21st century (TPACK) | 36 | 4.9% | 18.8% | |||

| System | Support | Systemic support for digital learning and innovation in Quality Teaching | 33 | 4.5% | 17.3% | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1 |

| Focus | SEL/SET | Theme | F | % of Total (F = 740) | % of Domain (f = 137) | Mean | SD | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learner | Total | 97 | 13.1% | 70.8% | 0.6 | 0.8 | 2 | |

| SEL and self-direction | Social learning, self-direction, and emotional-motivational learning | 52 | 7.0% | 38.0% | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| characteristics | Learner SE characteristics related to learning | 45 | 6.1% | 32.8% | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Teacher | characteristics | Teacher SE characteristics related to Quality Teaching | 40 | 5.4% | 29.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Halfon, E. Reconceptualizing Quality Teaching: Insights Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010037

Halfon E. Reconceptualizing Quality Teaching: Insights Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalfon, Ester. 2026. "Reconceptualizing Quality Teaching: Insights Based on a Systematic Literature Review" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010037

APA StyleHalfon, E. (2026). Reconceptualizing Quality Teaching: Insights Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Education Sciences, 16(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010037