1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is twofold. First, it examines the beliefs of pre-primary and primary student teachers (STs) at the University Autónoma of Madrid (UAM) regarding the impact of bilingual education programs (BEPs) on children’s learning experiences at both educational stages. In particular, it explores how STs perceive the benefits and challenges associated with Content and Language Integrated Learning methodology (CLIL) in pre-primary and primary education. Second, this study aims to examine the underlying reasons for these beliefs among the two trainee groups, highlighting both their differences and commonalities. By comparing their perspectives, this paper seeks to determine whether the distinct curricular characteristics of pre-primary and primary education influence trainees’ beliefs about BEPs.

Teachers’ beliefs are conceptualized here as “a form of thought, constructions of reality, ways of seeing and perceiving the world and its phenomena, which are co-constructed within our experiences, and which result from an interactive process of interpretation and (re)signifying and of being in the world and doing things with others” (Barcelos, 2014, in

Kalaja et al., 2016, p. 123). Teachers’ beliefs have been widely examined in educational research because of their strong influence on teachers’ attitudes, classroom practices, and pedagogical decision-making (

Borg, 2001;

Bustos, 2001;

Kuzborska, 2011;

Pajares, 1992). Building on this line of inquiry, the present case study forms part of a broader research project undertaken collaboratively by the UAM DAIC research group

1 that investigates the perspectives of various stakeholders engaged in BEPs across different instructional contexts (

Alonso-Belmonte, 2024;

Alonso-Belmonte & Fernández-Agüero, 2021;

Fernández-Agüero & Mañoso-Pacheco, 2026;

Mañoso-Pacheco & Sánchez-Cabrero, 2022; among others).

In Spain, BEPs are widely implemented in state primary schools. The region of Madrid provides a clear example: the Programa Bilingüe is offered in 46.6% of public primary schools, and in the 2024–2025 academic year, 35 of the 369 public bilingual schools extended the program to the second cycle of early childhood education (ages 3 to 6). Against this backdrop, it is highly likely that the professional careers of both pre-primary and primary STs will unfold within the framework of regional BEPs.

In recent years, a growing body of research in Spain has investigated teachers’ perceptions of BEPs, often with the aim of identifying their strengths, limitations, and areas for improvement. Although the quality and implementation of BEPs vary across schools and regions, existing studies consistently emphasize the need for greater resource allocation, enhanced teacher training, and improved coordination among educational stakeholders—particularly in CLIL settings at the primary level (

Cabezuelo & Fernández, 2014;

Fernández & Halbach, 2011;

Pena Díaz & Porto Requejo, 2008;

Szczesniak & Muñoz Luna, 2022). With regard to pre-primary education, research remains limited (

Cortina-Pérez & Pino Rodríguez, 2021;

Du Plessis & Louw, 2008). Overall, early education teachers hold positive expectations about the potential benefits of CLIL for both learners and educators. Nevertheless, many do not feel adequately prepared to implement it at the pre-primary level, largely due to the limited availability of teacher training programs (both in methodology and foreign language communicative competence) and the scarcity of resources such as guidelines, teaching materials, and institutional support (

Segura, 2023).

STs’ beliefs remain relatively underexplored in recent literature, despite their crucial role in shaping future teaching practices. They act as filters through which new pedagogical knowledge is interpreted and assimilated. Deeply grounded in personal experiences, prior knowledge, and mental models, these beliefs tend to resist change. Consequently, new ideas introduced during teacher training interact with, rather than replace, pre-existing conceptions. Understanding how such beliefs influence and respond to training experiences is therefore key to designing more effective teacher education programs.

The findings from the UAM DAIC research group suggest that the perceptions of primary and pre-primary STs regarding BEPs are shaped by a range of interrelated factors. One such factor is their level of English proficiency. As noted by

Mañoso-Pacheco and Sánchez-Cabrero (

2022), the higher the STs’ command of English, the more critically they tend to assess BEPs. In contrast, STs with lower English proficiency tend to evaluate BEPs more positively. Another influential factor is STs’ emerging professional identity—that is, how they envision themselves as future educators and their role within bilingual education contexts. According to

Alonso-Belmonte (

2024), many STs express a strong identification with their subject area and perceive CLIL as an externally imposed methodology that may hinder their future teaching practice, leading to a largely negative evaluation of the approach. What remains to be explored in this research project is whether the degree of specialization of STs—primary or pre-primary—plays any role in shaping their perceptions; in other words, whether the characteristics of the educational stage for which STs are being trained influence their attitudes towards BEPs. Thus, the objectives of this paper are:

to examine pre-primary and primary STs’ beliefs at the UAM about the impact of BEPs on children’s learning experience in CLIL contexts, as well as the underlying reasons for these beliefs.

to compare the beliefs of these two trainee groups, identifying differences and commonalities.

2. Benefits and Challenges of Bilingual Education: A Review of the Literature

CLIL, which integrates foreign language learning with subject-matter instruction, provides the methodological foundation for BEPs. A substantial body of research has documented its benefits in both pre-primary (

Otto & Cortina-Pérez, 2023) and primary education (

Dafouz & Guerrini, 2009;

Lasagabaster & Ruiz de Zarobe, 2010). One consistently reported advantage is the development of communicative language skills. Empirical studies show that CLIL fosters students’ linguistic competence (

Jiménez-Catalán & Ruiz de Zarobe, 2009), a finding that aligns with official data provided by the regional government of Madrid, which reports that 82% of sixth-grade pupils in bilingual public schools reach the expected proficiency level in external assessments (

Comunidad de Madrid, 2018). Moreover, research consistently highlights the positive impact of CLIL on students’ motivation, demonstrating that learners exposed to CLIL programs—even at younger ages—tend to show higher engagement and enthusiasm compared to their peers in non-CLIL settings (

Azpilicueta-Martínez & Lázaro-Ibarrola, 2023;

Lasagabaster & López Beloqui, 2015).

Another strand of research underscores CLIL’s contribution to cognitive development and critical thinking. Studies indicate that specific skills such as predicting, comparing, organizing, and problem-solving—and the associated language—are more effectively developed in CLIL contexts, where learners must engage with the academic and cognitive demands of subject learning through a foreign language (

Coyle, 2005;

Coyle et al., 2009). In pre-primary education, some scholars stress the value of fostering early cognitive growth as a foundation for later academic challenges (

Fernández-Agüero & Alonso-Belmonte, 2023). Although this may be demanding for very young learners, it becomes attainable when supported by appropriate scaffolding, the encouragement of broad creativity, an emphasis on discovery-based learning, and the strategic use of translanguaging.

Despite these well-documented benefits, the findings highlight a discrepancy between this theoretical framework and certain observational evidence gathered from classroom practice. An example of this gap is the limited integration of intercultural education within CLIL real practice. Even though all regional governments in Spain employ language assistants to promote multiculturalism and linguistic diversity in schools, this policy support does not always translate into effective classroom implementation. As

Pérez-Gracia et al. (

2017, p. 97) observe, “not many [primary teachers] have an idea of what intercultural competence is and how they can help students achieve it.” Consequently, intercultural education often remains superficial, restricted to isolated cultural facts or celebrations rather than being embedded in meaningful, critical, and reflective learning experiences. As

Gómez-Parra (

2018) compellingly argues, “intercultural education is not accomplished by the simple addition of culture-related contents to a specific approach. It rather entails the specific design of an educational bilingual program whose main axis is found in intercultural education (…) It involves the design of an approach where culture is at the very center of learning, which articulates and vehicles contents” (p. 94).

Similarly, although research consistently highlights the cognitive benefits of CLIL in promoting higher-order thinking skills, observational evidence also suggests that, in primary education, most reported CLIL practices remain limited to activities such as reviewing and activating prior knowledge before engaging with a text. Subsequent tasks often focus predominantly on lower-order thinking skills (

Alonso-Belmonte & Fernández-Agüero, 2018;

Gerena & Ramírez-Verdugo, 2014). Such discrepancies between theory and practice, as observed by STs, may significantly influence their beliefs and attitudes toward CLIL, and can largely be attributed to the persistent challenge of insufficient teacher preparation. As several studies indicate, many teachers possess only a limited repertoire of strategies to foster critical and creative thinking within CLIL lessons (

Campillo-Ferrer et al., 2020). This imbalance may ultimately hinder the implementation of the deeper cognitive objectives that CLIL is intended to achieve.

Further criticism concerns BEPs’ potential to deepen educational inequalities. While BEPs are intended to provide students from diverse socio-economic backgrounds with equal opportunities to learn foreign languages, their real implementation in some regions suggests that they may, in practice, contribute to the opposite effect, particularly at the secondary level, where differences in students’ linguistic and academic readiness become more pronounced (

Alonso-Belmonte & Fernández-Agüero, 2021;

Cortázar & Taberner, 2020).

Finally, although CLIL can significantly enhance learners’ intrinsic motivation, it can also pose additional difficulties for students with learning differences or special educational needs, who may struggle to process subject content and a second language simultaneously. As

Martín-Pastor and Durán Martínez (

2019) note, many bilingual programs lack adequate support for such learners. The resulting cognitive overload can reduce motivation and academic engagement, particularly among students already facing challenges in learning a foreign language.

In sum, while CLIL represents a powerful pedagogical approach that effectively integrates content and language learning—promoting linguistic competence, cognitive development, motivation, and intercultural awareness—, its implementation is highly dependent on contextual factors such as regional government policies, the quality of in-service teacher training, and the diverse profiles of students enrolled in BEPs. Variations in these factors can lead to significant differences in how CLIL is enacted in classrooms, sometimes resulting in a gap between theoretical expectations and practical realities. This mismatch can, in turn, affect STs’ beliefs and perceptions regarding the effectiveness of BEPs.

3. Materials & Methods

3.1. Method & Data

To address the objectives of this paper, data were drawn from a questionnaire completed by 170 prospective pre-primary and primary teachers at the UAM. The instrument, whose characteristics and validity are described in

Mañoso-Pacheco and Sánchez-Cabrero (

2022), comprised 24 items, five of which (nos. 19, 20, 21, 22 & 23) are particularly relevant to this study. Item 19 is a closed-ended question about whether STs believe BEPs enhance or hinder students’ learning experiences at the pre-primary or primary level. Items 20–23 present STs with a range of possible reasons on a rating scale, with items 20 and 21 focusing on why BEPs are perceived as beneficial and items 22 and 23 on why they are seen as detrimental. These reasons were identified and selected in light of the findings and discussions presented in the literature review in

Section 2 and are summarized here:

BPs improves students’ learning experience because: (a) it increases motivation among students; (b) it develops cognitive skills; (c) it enhances communicative skills; (d) it promotes multicultural education.

BPs worsens students’ learning experience because (a) it increases the social gap among children; (b) it involves added difficulty for students with learning difficulties and special needs; (c) it demotivates students with learning difficulties; (d) it lowers teaching standards due to the frequent lack of methodological training or L2 linguistic competence.

STs’ responses to items 20–23 were rated on a four-point Likert scale (1 = not important, 2 = barely important, 3 = quite important, 4 = very important). The sample of STs’ answers analyzed is available in the multidisciplinary research data repository e-cienciaDatos. Surveyed STs were informed about the aims of this research and assured that their responses would remain anonymous and be used solely for research purposes. All participants took part voluntarily and provided their informed consent.

3.2. Informants

As reported in

Mañoso-Pacheco and Sánchez-Cabrero (

2022) and in

Alonso-Belmonte (

2024), most participants were Spanish female students (85.5%) in their twenties (90.6%), most of them in the third year of their degree (62.4%). The surveyed STs were enrolled in the Primary Education Degree, the Nursery Education Degree, and the Joint Degree in Nursery and Primary Education at the UAM, in the proportions indicated in

Table 1.

At the UAM, STs in their second and third years receive general pedagogical training (not specifically focused on CLIL) and complete a school internship lasting several weeks where they are able to observe real class practice

2. All participants in the survey reported having observed the implementation of BEPs during their third-year internships in schools across the Madrid region.

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Results

As shown in

Table 2, nearly half of STs (47%) believe that BPs enhance the learning experience of students in both pre-primary and primary education. In contrast, one in five STs (20%) regard BPs as unfavorable at both stages, suggesting a critical stance toward their effectiveness.

Interestingly, some STs provided more nuanced views. While 22.9% felt that BPs are beneficial only at the pre-primary stage, a smaller group (4.7%) held the opposite view, suggesting that the program is not effective in primary. These differences indicate that STs are attentive to how educational practices may function differently across developmental stages. The possible reasons behind these perspectives are examined in the next section.

4.2. Main Aspects Enhanced by BEPs in Pre-Primary and Primary Education

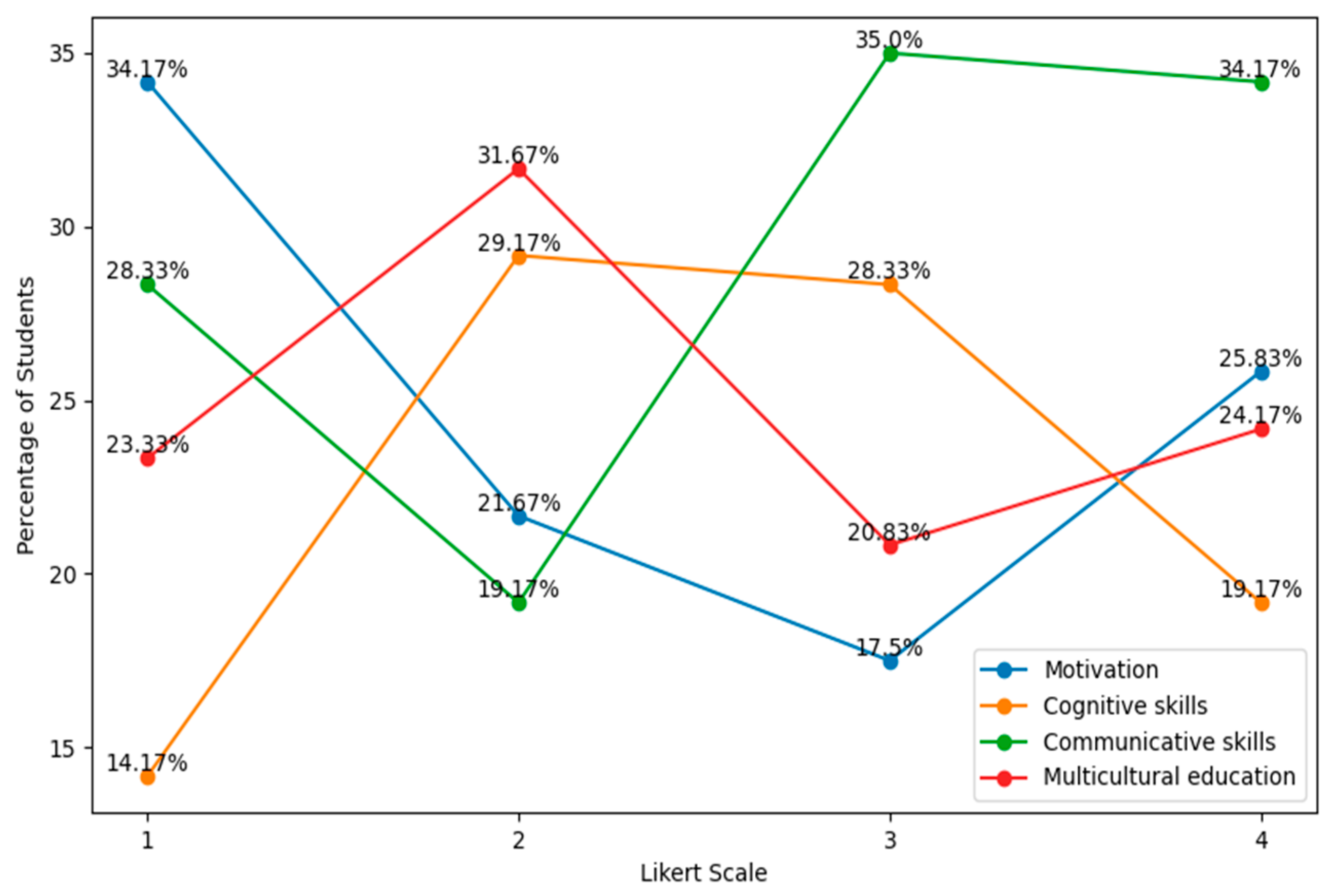

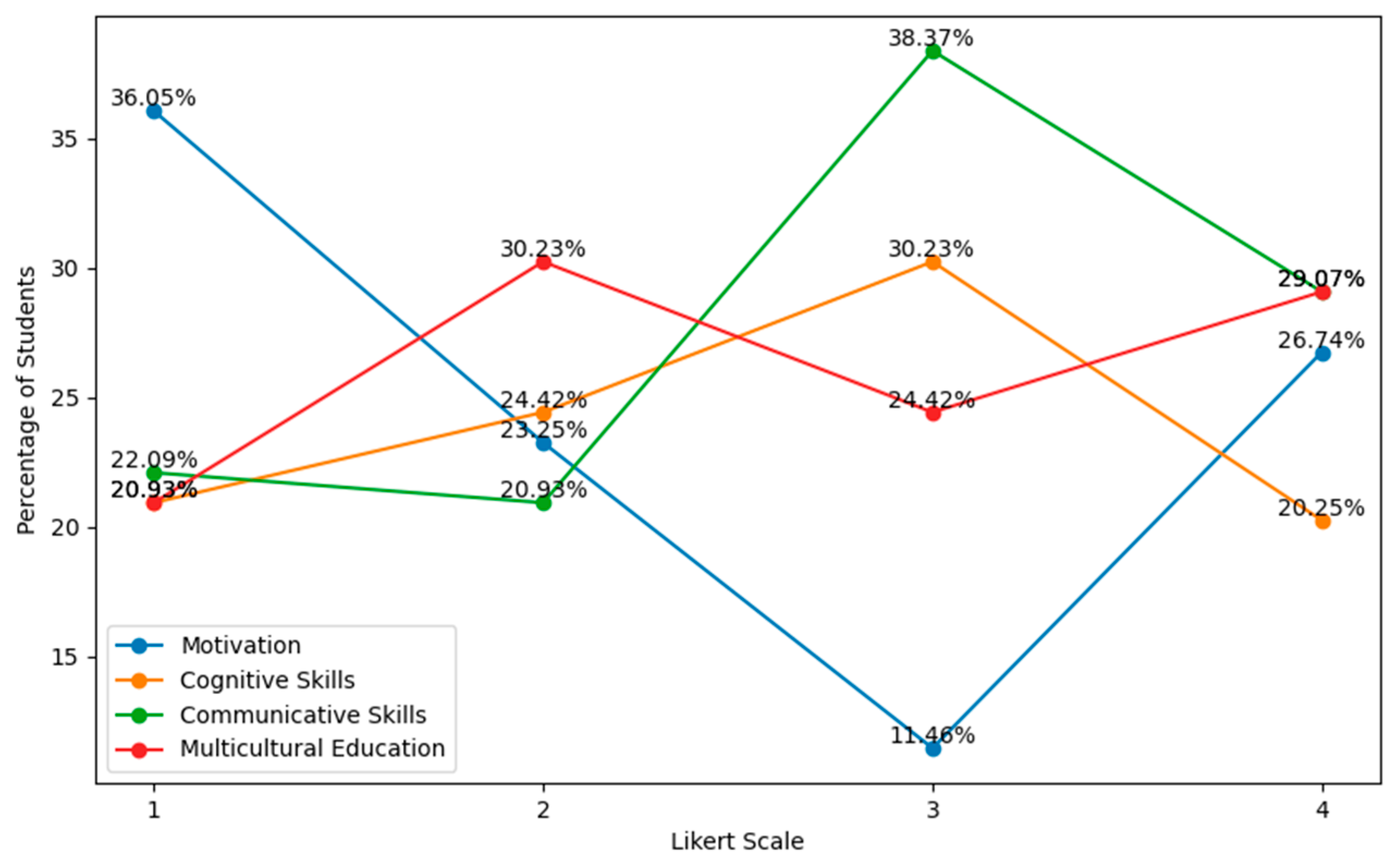

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 present the distribution of responses of pre-primary and primary STs by Likert scale option (1 to 4). Each curve represents a factor, highlighted in a different colour, and the percentages indicate how many trainees rated that factor at each importance level:

As figures show, both datasets reveal largely similar opinions. The main reason provided by both pre-primary and primary STs to claim that BPS enhance students’ learning process is the “enhancement of communicative skills in English”, followed by the “development of cognitive skills associated with bilingual speakers”. By contrast, the promotion of multicultural education and increased motivation are viewed as less important outcomes of BPs.

There are also some slight differences between the two groups. For example, while both groups express strong agreement on the relevance of BPs for enhancing communicative skills, pre-primary trainees show a slightly stronger and more unified endorsement. Most rated it as “Quite important” (3) or “Very important” (4), in comparison to the answers provided by their primary counterparts. This tendency can be attributed to the widespread belief that early childhood education is fundamentally rooted in communication, as interaction and language are viewed as the primary vehicles for learning and socio-cognitive development at this stage. By contrast, primary trainees may regard communication as just one of several essential competences to be cultivated in primary education, where the emphasis tends to be broader, encompassing literacy, numeracy, and subject-specific knowledge alongside social and communicative abilities.

Regarding the development of cognitive skills, primary trainees are the ones who display a stronger and more consistent belief in the cognitive benefits of bilingual programs. In fact, they register the highest percentage at the “Quite Important” level (30.23%), with a relatively balanced distribution across the remaining categories. By contrast, pre-primary STs present more neutral attitudes, with 29.17% selecting option 2 (“barely important”) and 28.33% opting for option 3 (“quite important”). This tendency may reflect primary STs’ awareness of the cognitive demands of subject learning through a foreign language and their focus on academic achievement in CLIL contexts, likely shaped by their practicum experience observing classroom teaching practice in Primary schools.

Responses concerning the impact of BEPs on multicultural education were mixed and showed little variation between the two groups. Pre-primary trainees exhibited a slight tendency toward options 1 (“not important”) and 2 (“barely important”), indicating that they regarded multicultural education as somewhat less important than their primary counterparts. Finally, with regard to motivation, responses were highly polarized in both groups, with primary trainees appearing slightly more skeptical about its importance, although the difference is far from significant.

4.3. Main Aspects Hindered by BEPs in Pre-Primary and Primary Education

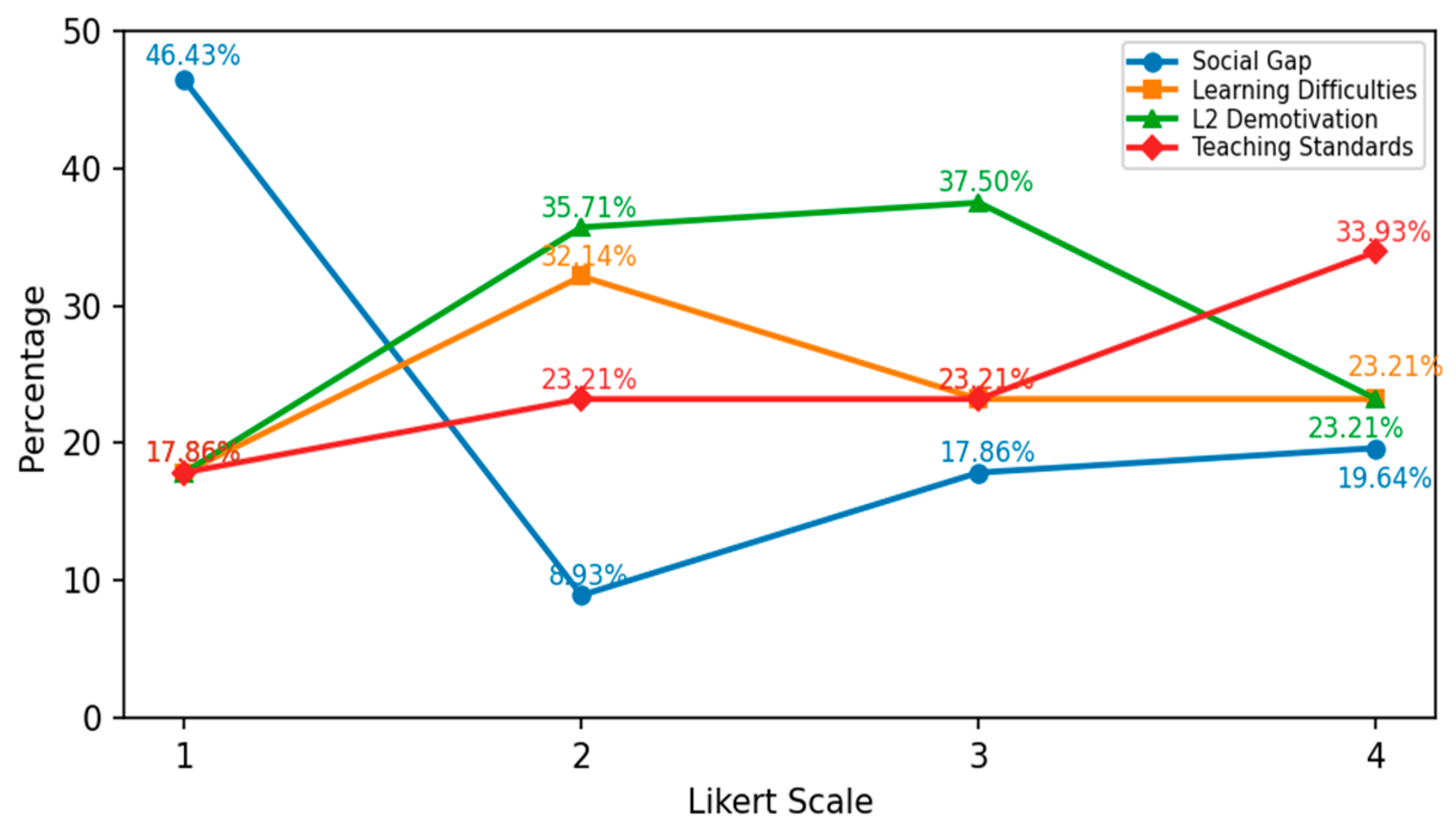

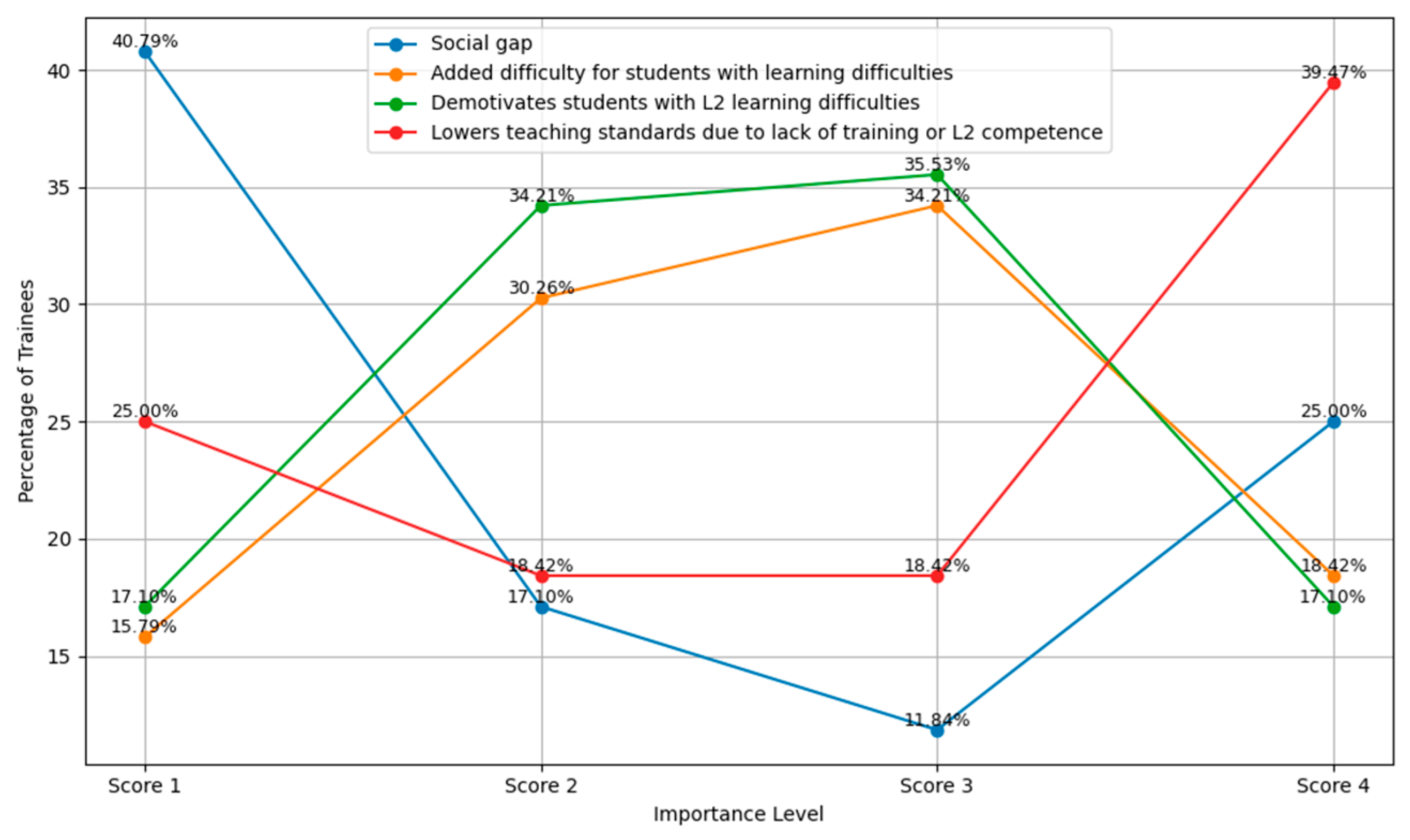

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present the distribution of responses of pre-primary and primary STs by Likert scale option (1 to 4), including the relative percentages associated with each response category:

Regarding the reasons attributed to the negative effects of the BPs, respondents appear to agree on both the most and least relevant criteria across educational stages. Both groups of trainees hold a strong awareness of how bilingual education can pose challenges for students with learning difficulties. A common concern is the potential link between BPs and the demotivation of students with L2 learning difficulties, which in turn could diminish their engagement and ultimately hinder their academic progress. Within this perspective, pre-primary trainees display greater concern about the dangers of demotivation, highlighting their sensitivity to the affective dimension of learning.

Another main concern is the teaching standards, particularly among primary STs. This factor received the highest “very important” rating (39.47%). Only 25% of the surveyed primary STs said it was not important. This reflects a strong concern among primary trainees about the quality of teaching in bilingual settings, especially when teachers lack proper training or language skills.

As for their minor concerns, social inequality is not widely perceived as a major barrier to bilingual education. Both groups of trainees seem to agree on this, although primary trainees show slightly more concern.

5. Discussion

Overall, the findings suggest a shared perception among STs that BEPs enhance the students’ learning experience in both pre-primary and primary education. Most respondents acknowledge the advantages of CLIL in improving language proficiency and fostering cognitive development, a view that aligns with previous research and reflects an overall positive attitude toward bilingual education. Nevertheless, although the surveyed STs acknowledge the benefits of CLIL, they also point out key challenges such as teacher training and L2 learner motivation, as well as the difficulties experienced by students with learning problems, showing their awareness of the potential barriers to effective implementation. Regarding social inequality, it is generally viewed as a minor issue by both groups, in contrast to findings from secondary education contexts, where concerns about unequal access to bilingual programs and disparities in student outcomes are more pronounced (

Alonso-Belmonte & Fernández-Agüero, 2021). This relative lack of concern among pre-primary and primary trainees may stem from limited exposure to the structural inequalities that become more evident in later stages of schooling.

Two additional aspects—multicultural education and increased learner motivation—were perceived by STs as less significant outcomes of BEP implementation. This limited emphasis may stem from their direct classroom observations during their school placements, where language-focused tasks often take precedence over intercultural development, and where some students may display lower levels of motivation than those reported in research. Although any potential relationship between school-based training experiences and STs’ beliefs regarding BEPs has yet to be examined in depth, this perception relates to another reported drawback of BEPs, particularly noted by primary STs: the lack of effective teacher training in CLIL. Recent research in Spain has similarly highlighted this issue. In fact, studies indicate that many teachers tend to prioritize improving their own English proficiency over developing the methodological expertise required to design cognitively demanding, interculturally grounded, and linguistically accessible learning experiences (

Durán Martínez & Beltrán Llavador, 2020). Hence, there is an urgent need for both pre-service and in-service teacher training programs that explicitly focus on developing the methodological strategies required to promote cognitive and intercultural development, motivation, and learner engagement in CLIL contexts. There is also a need for closer collaboration between university-based training programs and school-based training experiences. Strengthening this collaboration would promote consistent, high-quality mentoring and ensure a coherent approach to teacher preparation—one that effectively bridges theoretical instruction and practical classroom experience. This is especially important in Spanish pre-primary education programs, where CLIL training remains limited or even absent.

The integration of interculturality in CLIL requires learning to make a profound curricular reorientation—one that places culture at the core of learning objectives and materials. Such training should not only raise awareness of cultural diversity but also provide concrete classroom practices that promote dialogue, critical thinking, and cross-cultural understanding. Likewise, fostering motivation among all students demands inclusive practices that promote accessibility and balance linguistic and cognitive demands to ensure meaningful participation for all learners. Together, these measures can help bridge the gap between CLIL potential and real classroom practice, enhancing both the educational experience and learning outcomes in CLIL settings.

In response to objective No. 2, no major differences were found between the two groups of STs surveyed. While overall patterns are largely consistent, subtle variations emerge, revealing two distinct teaching profiles among the trainees. Primary STs tend to display greater sensitivity to structural and pedagogical issues, particularly in relation to teaching standards. This heightened critical awareness may reflect their focus on academic achievement and measurable learning outcomes, which are central to the primary education stage. In contrast, pre-primary trainees appear less critical overall and more attuned to the social and emotional dimensions of learning. They show stronger support for the development of communicative skills and express greater concern for learners’ motivation and emotional well-being, especially in relation to students who experience learning difficulties. This emphasis likely stems from the developmental orientation of early childhood education, where communication and affective engagement are viewed as foundational for learning and growth. This suggests that the training STs receive—both on-campus and at schools—may play a significant role in shaping their opinions and perceptions. Although this influence requires further investigation, these observed distinctions between primary and pre-primary STs could have important implications for teacher training programs. The greater sensitivity of primary STs to structural and pedagogical issues could also indicate a potential need to strengthen their exposure to socio-emotional dimensions of learning, ensuring they are equipped to address students’ motivational and affective needs alongside academic objectives. One way to achieve this is by embedding case studies, role-playing activities, or collaborative projects into their training programme, requiring STs to consider how learners’ emotional engagement and interpersonal dynamics influence learning processes. In contrast, pre-primary STs’ stronger emphasis on social and emotional aspects suggests a need to further strengthen their understanding of CLIL and their training in specific CLIL pedagogical strategies specifically suited to Early Education. This might involve offering modules on CLIL methodology tailored to young learners, providing model lessons delivered by experienced CLIL teachers, and incorporating hands-on micro-teaching sessions in which STs practise scaffolding content while supporting early language development. Additionally, reflective tasks and guided observations of CLIL classrooms can further strengthen their awareness of effective instructional approaches, helping them learn to balance socio-emotional engagement with structured content and language learning.

6. Conclusions

This analysis should be regarded as an initial exploratory step that lays the foundation for more extensive and systematic research in the future. Given that it relies on a limited dataset—specifically, responses to six items from a structured questionnaire, it offers only a preliminary and necessarily impressionistic picture of UAM prospective teachers’ beliefs about BEPs and the reasons behind it. Despite these limitations, this study provides meaningful insights into how future teachers perceive bilingual education programs and highlights emerging patterns worth examining in greater depth. These findings can serve as a starting point for more robust, mixed-methods research and for the refinement of teacher education programs, ensuring that future bilingual educators receive targeted support aligned with the realities of classroom practice. The use of the questionnaire in itself already provides a solid guarantee of replicability, as it can be easily administered to larger and more diverse cohorts of STs—both within and beyond the UAM and across academic years, degree programmes, and institutional contexts. This facilitates meaningful comparisons of findings over time and across settings, enabling future studies to validate, refine, or challenge the patterns identified in the present analysis.