1. Introduction

Over the past decade, virtual education has become an increasingly relevant and widely adopted modality within the university context. The advancement of information and communication technologies (ICTs), together with the growing demand for flexibility and accessibility in higher education, has led to the proliferation of programs and courses in various formats, marking a shift from the historically dominant face-to-face model.

In this sense, this modality emerges from the evolution of distance education, which, in the Colombian context, has been categorized into several generations—the third being designated as “virtual education” or “online education”, according to the Ministry of National Education (MEN).

Within this landscape, the adoption and effectiveness of this training modality depend not only on technological infrastructure and pedagogical resources but also on the perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs of the actors involved in the educational process. In this context, the social imaginaries of university professors play a crucial role in the implementation and development of virtual education—an aspect explored in depth throughout this article.

Social imaginaries refer to collective representations and symbolic constructions that individuals and social groups build from the various dimensions that shape their reality. These imaginaries influence how people interpret and perform within their environments. In the case of university faculty, they condition the acceptance, appropriation, and valuation of virtual methodologies and the technical framework surrounding them. Understanding these imaginaries is essential for identifying the opportunities and challenges facing virtual education in universities and, likewise, for designing strategies that facilitate its effective integration into teaching and learning processes.

This aspect gains particular relevance given that, according to MEN indicators, between 2019 and 2023, the number of university students enrolled in virtual academic programs in Colombia increased by 234%, from 221,625 to 518,068 across undergraduate and graduate levels. This scenario underscores the need to strengthen teaching and learning processes in digital contexts—an effort that must be shared by higher education institutions and faculty, who are responsible for designing and implementing pedagogical and didactic strategies aligned with the demands of virtual learning and the expectations of their students.

Universities, therefore, must generate professional development strategies that spark faculty interest and motivation, responding to their needs as educators in environments different from face-to-face settings. This entails providing appropriate tools for designing innovative teaching strategies that foster meaningful learning experiences. Addressing this need requires institutional support grounded in listening processes that unveil the imaginaries emerging from teachers’ uncertainties and certainties regarding virtual education and its implications for pedagogical practice.

In this regard,

Cuevas (

2020) asserts that “the social imaginary concerns the various worldviews, constituting a constantly changing form of expression and an indirect mechanism of reproduction.” This transformation invites a deeper understanding of singularity through a panorama built collectively by each actor within the field of virtual higher education. Consequently, it becomes possible to approach the perceptions of specific groups regarding how they interpret certain realities, as various authors examining social imaginaries suggest.

Rogozin et al. (

2022) identify a positive trend in university professors’ attitudes toward digital transformation, highlighting a shift from discontent to a more balanced view of online learning, recognizing the potential benefits of technology in innovative learning processes.

Similarly,

Facco et al. (

2019) note that “from this perspective, we can think of the subject as a magma of incessant creative imaginations—an unfinished being, open to change and contextual transience.” This perspective invites new ways of seeing and perceiving university faculty as evolving, transforming, and reinventing themselves to face the challenges of contemporary higher education.

This research article thus seeks to explore the social imaginaries of university professors regarding virtual education, analyzing their mental constructions and stances toward this modality. Through this investigation, we aim to refine and articulate key definitions and aspects emerging from teachers’ voices—beyond the national regulations and institutional guidelines that traditionally frame the educational discourse. Adopting a qualitative approach, the study seeks to capture the diversity and complexity of social representations that the faculty of Simón Bolívar University, Cúcuta campus (Colombia) collectively construct around virtual education, as well as the implications of these imaginaries for their teaching practice and students’ learning experiences.

To this end, a focus group and semi-structured interview guide were used, grounded in the categorical dimensions derived from the theoretical and empirical exploration of the topic. This methodological design enabled a deep and nuanced understanding of professors’ social imaginaries, offering key insights to conceptualize virtual university education in a way that reflects the lived experiences of those who teach in such contexts. Finally, the analysis—conducted through grounded theory—wove together the findings, allowing for the construction of a cartography of subjectivities around professors’ representations and imaginaries of virtual education.

Drawing from the existing literature on social imaginaries and virtual university education, the study presents its methodological framework and discusses the resulting findings. The research contributes to knowledge about the social and cultural dynamics influencing virtual education, while proposing practical recommendations to strengthen this modality as part of the commitment to quality in higher education.

Despite the growing body of research on virtual higher education, most studies have focused on technological, administrative, or academic performance aspects, leaving aside the symbolic and subjective dimensions that shape teachers’ engagement with this modality. Thus, a gap remains in understanding how faculty’s social imaginaries shape their relationship with virtuality, influence their pedagogical practices, and determine their perceptions of educational quality. From this perspective, the present study offers an inductive and situated approach that constructs a cartography of university faculty subjectivities regarding virtual education, revealing tensions between innovation and resistance, as well as the personal, institutional, and pedagogical factors shaping these representations. This contribution seeks to expand understanding of the cultural and formative dynamics mediating the transformation of university teaching in Latin American digital contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Between Representation and Experience: Teachers’ Social Imaginaries in the Field of Virtual Education

Virtual education, as an expanding phenomenon, has not only transformed the dynamics of teaching and learning but has also shaped new ways in which teachers represent and experience their role in these environments. This section reviews the literature that helps to understand how the social imaginaries surrounding educational virtuality influence teachers’ perceptions, practices, and dispositions toward their pedagogical work. Thus, it establishes a dialogue between the symbolic representations constructed around technology-mediated education and the concrete experiences of the teachers who inhabit it.

Following

Cegarra (

2012), who states that “social imaginaries are symbolic constructions that shape collective perceptions of reality,” these imaginaries are interpreted as a unified voice that weaves together the feelings of collectives whose perspectives are often overlooked or silenced within their context to conform to socially imposed standards.

In this regard,

Castoriadis (

1997) asserts that “the instituting social imaginary constitutes the symbolic foundation of every institution,” introducing a radical rupture with traditional ways of understanding the origin and structure of social order. Rather than assuming that institutions emerge solely from instrumental rationality, political will, or functional necessity, Castoriadis argues that their genesis lies at a deeper level: within the symbolic realm of what is collectively imagined. This perspective does not regard the imaginary as mere fantasy or illusion but as a creative force—an instituting power that gives meaning, legitimacy, and form to social practices, norms, and structures. From this view, institutions such as the university, the school, or even virtual education are not neutral or natural entities but historical and cultural products sustained by shared significations. These meanings are neither universal nor fixed; they are in constant motion—always open to transformation or even subversion.

Within the educational context, imaginaries allow us to understand that teaching, the teacher’s role, the curriculum, and learning modalities cannot be analyzed solely through educational policy or a purely instrumental technological logic. It is essential to question the imaginaries that underlie and sustain them: What is imagined as “good teaching”? What is represented as “presence” or “absence” in virtual settings? What meanings circulate around the pedagogical relationship in the absence of physical contact?

From this perspective, the instituting social imaginary is performative: it creates possible worlds, inaugurates new realities, and organizes the meaning of experiences. For example, the emergence of virtual education is not merely the result of technological advancement; it is also the expression of a new imaginary about time, knowledge, and human relations. It represents a way of understanding learning that transcends physical classrooms and reconfigures the pedagogical bond through ubiquity, connectivity, and immediacy.

However, this instituting imaginary often encounters resistance from the instituted one—that is, from traditional representations that reproduce inherited models and resist change. In the teaching field, this tension manifests between those who imagine virtual education as an opportunity and those who perceive it as a threat or a form of dehumanization. These frictions reveal a symbolic struggle between competing imaginaries: one instituting, which proposes new possibilities; and one instituted, which seeks to preserve the familiar.

Therefore, to understand Castoriadis is to accept that every structural change—in institutions, pedagogical practices, or educational forms—first requires a transformation in the symbolic order. There is no transformation without a shift in imaginaries. Hence, the work of the researcher, the educator, and the critical teacher consists of making these imaginaries visible, deconstructing their assumptions, and opening spaces for new ways of imagining the educational world.

In short, Castoriadis challenges us with a powerful and provocative truth: the social world is not given; it is created. And within this creation, education represents one of the privileged arenas where imaginaries converge, conflict, and eventually transform.

As

Chávez Blanco (

2022) points out, “the imaginaries that drive online education point to a change in cultural logics rather than merely technological ones.” For this reason, listening to, analyzing, and understanding teachers’ perspectives becomes essential during processes of transition and appropriation of technology-mediated university education within higher education institutions.

2.2. Between the Instrumental and the Reflective: Approaches to University Teachers’ Digital Competencies

From a general perspective,

Buils et al. (

2022) argue that “frameworks for teaching competencies in higher education focus on a partial, instrumental, and teacher-centered digital vision.” Establishing such frameworks is important, as they serve as guides for designing professional development strategies that respond to current educational dynamics, while allowing for the assessment of teaching performance throughout the academic trajectory and fostering more flexible and innovative pedagogical practices.

However, in practice, understanding digital competence requires a holistic vision—one that integrates teachers’ needs, uncertainties, and aspirations, while also engaging with students’ learning expectations in a world dominated by technology.

It is therefore worth rethinking models that better respond to the realities of education in digital contexts, as

Esteve et al. (

2018) propose, by moving beyond restrictive concepts that reduce teaching to classroom performance and view technology through a merely instrumental lens. For these authors, teachers should be understood as generators of digital pedagogical practices and content—professionals who use technology with social commitment to expand their relationship with the students’ environment.

In this same vein,

Suárez et al. (

2021) propose an analytical framework for digital teaching competence in professional education that integrates pedagogy, resources, and assessment to understand, evaluate, and improve teachers’ digital capacities. Their analysis focuses on four technology-supported learning scenarios: individual learning, ICT-based teaching, collaborative learning, and student self-learning—thus offering an integrative perspective on the competencies necessary for effective teaching practice.

From this, it becomes crucial to identify the challenges and perspectives of virtual education considering university teachers’ digital competence. As

Cruz et al. (

2022) highlight, teachers must reflect in their practice the technological knowledge acquired and continually adapt these competencies to diverse contexts to meet the demands of 21st-century education.

Torres-Barzabal et al. (

2022) suggest that developing digital competencies must begin with self-awareness—a reflective process through which teachers uncover their familiarity with technological tools used in university education. This awareness, as

Vargas-Angulo (

2024) points out, is vital to recognizing what is needed to propose “specific adjustments grounded in the uniqueness of the context, the educational institution, and its educators.”

From this viewpoint,

Holguín-Álvarez et al. (

2021) argue that digital competence should also be analyzed through the lens of teacher resilience—the ability to face difficulties and strengthen performance in virtual teaching modalities. This perspective sheds light on teachers’ emotions, imaginaries, uncertainties, and challenges in the digital era, acknowledging the emotional dimension and its impact on virtual teaching and learning processes.

This shift—from an operational understanding of digital skills to a critical and integral comprehension—recognizes that technological knowledge cannot be dissociated from pedagogical knowledge or professional identity. Treating digital competence as part of teachers’ subjectivity implies moving beyond the technical–instrumental focus that has long dominated training frameworks and embracing a vision in which the digital becomes a space for reconfiguring knowledge, pedagogical relationships, and educational intentionality. It is not merely about using tools, but about transforming how educators think, design, and engage with learning processes, while acknowledging the tensions, resistances, and possibilities that emerge in technology-mediated university contexts.

In this sense, discussing digital competence in contemporary higher education requires incorporating ethical, emotional, and social dimensions that permeate teaching practice. Technological proficiency is not only a technical ability but also a stance toward the world. Virtual education demands openness to new languages, new ways of narrating knowledge, and new modes of inhabiting the digital classroom. Therefore, teacher training must create spaces for reflective dialogue, exploration of imaginaries, and collective construction of meaning about the digital, enabling teachers to re-signify their role and respond creatively and critically to the challenges of 21st-century university education.

2.3. University and Virtuality: New Educational Logics and Emerging Challenges for Teachers

The current landscape of higher education shows a steady increase in academic programs offered through non-face-to-face modalities, driven by the dynamics of the knowledge society. In this context, it is essential to adopt an integrated perspective on the difficulties universities face in their transition toward virtuality: the demand for new pedagogical strategies, the increase in teachers’ workload, the expansion of roles, and the tensions arising from technological appropriation and regional structural disparities.

Higher education institutions face particular challenges in Latin America, where the introduction and appropriation of information and communication technologies (ICT) in education have posed significant obstacles.

Vélez Holguín (

2020) notes that some of the greatest challenges universities encounter regarding online education involve political and economic interests, the varying levels of scientific and technological development determined by social conditions, the alignment with regulatory standards, and the pedagogical quality of online teaching—amid growing pressure to deliver high-quality education without restrictions.

Examining the specific pedagogical, organizational, and technological challenges that teachers face in virtual learning environments,

Sällberg and Folino (

2024) found that pedagogical issues often relate to workload management and time allocation. Teachers report high initial time investment, limited accessibility, lack of student responsiveness, social distance, and weak cognitive presence in online sessions as major concerns.

Expanding on these challenges,

Yan and Pourdavood (

2024) identified findings from both teacher and student perspectives. Teachers reported that technical issues were a predominant concern, especially for those less technologically skilled. They also expressed difficulties in assessing understanding and fostering dialogue due to limited real-time communication and the distractions that affect students’ engagement. Teachers expressed growing concern over low participation and students’ sense of detachment from the learning process, citing lack of motivation and reduced control over course content.

The transition to virtual university education cannot be understood merely as a technological shift or a reconfiguration of tools and platforms. It represents a profound epistemic and cultural transformation of the educational act, in which traditional conceptions of teaching, the teacher’s role, the pedagogical relationship, and the meaning of knowledge are being redefined. In this new landscape, teachers are not only asked to adapt but also to rethink themselves as formative agents in contexts where time, space, and interaction have been radically altered.

These challenges are not purely instrumental. Although technological gaps persist—particularly in Latin American realities marked by inequality—the most critical issue lies in how these conditions affect the relational, emotional, and ethical dimensions of education. Teachers are called not only to acquire new digital skills but also to develop a reflective attitude to critically and creatively address the dilemmas of virtual teaching. Virtuality has revealed the structural fragility of educational institutions but has also opened unprecedented opportunities to reconfigure pedagogical relationships, decentralize knowledge, and re-signify student autonomy.

In this regard, contemporary universities must revisit their educational models from a situated perspective—one that acknowledges global challenges while recognizing local realities. Teachers, more than content transmitters, become key mediators between technology, knowledge, and students’ subjectivities.

Therefore, it is urgent to move toward a critical pedagogy of virtuality—one that goes beyond the acquisition of technical skills to foster reflection, creativity, collaboration, and ethical formation. This process must be supported by robust institutional policies, ongoing professional development programs, and an ethical commitment to inclusion, care, and the dignification of teaching in digital environments. Only in this way can universities inhabit the virtual world critically and transformatively.

Based on

Table 1, the following categorical inter-relations were established as the foundation for the methodological process.

3. Research Aim

This study aimed to understand the subjectivities of the teaching staff at Simón Bolívar University in the city of Cúcuta (Colombia) regarding the social imaginaries associated with digital competencies, relationships with technology, and conceptions of quality that shape their professional identity and teaching practice in virtual education contexts. The purpose was to contribute to the future development of a formative model that rethinks and transforms innovative and reflective pedagogical practices in higher education within the framework of virtual learning.

4. Research Methodology, Methods, and Materials

The study was grounded in the socio-critical paradigm, which, from a holistic perspective, seeks to understand and interpret social phenomena. In line with this approach, a qualitative methodology was employed. According to

Padilla-Avalos and Marroquín-Soto (

2021), qualitative research seeks to interpret the constructed reality of an educational and social phenomenon through the voices of the participants. The study adopted a Participatory Action Research (PAR) design, which, from its critical and self-reflective perspective, allowed for the articulation of contributions to the improvement of the educational context, requiring those involved to act as active agents in the process, as emphasized by

Kemmis (

1992).

The research involved a total of 15 university professors from the Simón Bolívar University, Cúcuta campus, who provided the information necessary for the construction of a cartography of subjectivities and social imaginaries surrounding virtual higher education. Data collection was carried out through semi-structured interviews, which were validated by a panel of experts in the field of Educational Sciences. The experts evaluated the relevance, clarity, and adequacy of each category and question comprising the instrument.

In coherence with the declared socio-critical paradigm, this process sought to analyze the needs and uncertainties revealed through participants’ responses as fundamental inputs originating from the protagonists of the teaching act—those committed to the process and interested in contributing to the understanding of the phenomenon addressed by the study on virtual education in university contexts. As stated by

Alvarado and García (

2008), this approach “fosters horizontal communication so that members of the group can anticipate and implement possible options to overcome the difficulties that affect, dominate, or oppress them.”

For the data analysis, four theoretical categories were considered, defined from the initial literature review. These categories guided the construction of the analytical framework related to teachers’ imaginaries about virtual education: being a teacher and their training, didactic use of technology and its connection to Higher Education, teachers’ relationship with technology, and Quality in Virtual Education.

Using this instrument and the authors’ hermeneutic interpretation, based on their experience in pedagogical and digital didactic training processes, the analysis followed the stages proposed by Grounded Theory: coding, structuring, contrasting, and theorizing.

Accordingly, the study implemented Grounded Theory as proposed by

Glaser and Strauss (

1967) to analyze emerging data systematically, generating an inductive theory about the teachers’ social imaginaries.

The analysis began with an iterative process of open, axial, and selective coding. During the open coding phase, the researchers identified units of meaning from teachers’ narratives (e.g., P6-GFP). In the axial coding stage, open codes were grouped into broader codes to form intermediate categories and establish relationships. In the selective coding phase, these categories were connected to the previously established theoretical categories to identify saturation points in both analytical and emergent dimensions within the studied imaginaries. During the initial stages, this coding process was conducted independently by the three researchers. Later, contrast and consensus sessions were held to unify criteria and strengthen the reliability of the process.

The emergent theories were directed toward addressing the research objective, deriving theoretical insights from the data collected through the instrument and contrasting them using a triangulation matrix. This matrix involved constant comparison among interview data, institutional documents, and analytical memos generated during interpretation. This procedure enabled validation of the emergent categories and ensured the internal coherence of the results.

As

Vargas-Angulo (

2024) argues, the search for meaning in the collected data—aimed at identifying the most relevant aspects in the analysis of teachers’ imaginaries—guided the development of an inductive process woven from coding, categorization, and in-depth analysis as central axes. In this regard,

Figure 1 presents the application scheme of Grounded Theory.

The process began with the construction of memos, integrating theoretical ideas that emerged from teachers’ responses to each interview question. The most significant results, determined by the evaluation scale, were cross-referenced with the interpretation matrix, from which the narrative of each case was extracted. Subsequently, open coding was applied to the four categorical statements, allowing the identification of central attributes grounded in the data, which shaped the formulation of the core themes in the emerging theoretical framework.

From the socio-critical approach adopted in this Participatory Action Research (PAR), the researchers assumed a reflexive stance toward their role in the inquiry process. It was acknowledged that every interpretation is influenced by the experiences, beliefs, and academic trajectories of those conducting the research; therefore, ongoing self-reflection was encouraged regarding their own understandings of teacher education and virtual learning.

This reflexivity was expressed through the development of analytical memos and in collective discussion sessions where individual interpretations were contrasted with the narratives of participating teachers. The aim was to minimize bias and ensure the co-construction of meaning. Thus, the subjectivity of the researchers was not suppressed but rather recognized as an integral component of the dialogical process that characterizes socio-critical Participatory Action Research.

For data analysis, a systematic process based on Grounded Theory (

Glaser & Strauss, 1967) was applied. In the first phase, open coding was conducted to identify units of meaning within participants’ responses. Subsequently, through axial coding, these codes were grouped according to conceptual affinity, resulting in intermediate categories that reflected shared dimensions of teachers’ discourse. In the final stage, selective coding enabled the integration and articulation of categories into core themes, which served as the foundation for the formulation of semantic postulates and the networks represented in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. This constant comparative process ensured coherence across the different levels of analysis and supported the inductive construction of the emerging theory.

Once the selective categories were consolidated, a constant comparative analysis was carried out to identify similarities and differences among the emerging themes, leading to the establishment of descriptive categories that guided the subsequent definition of the semantic postulates derived from the implemented coding process. Following these analytical stages, a formal theory was generated based on the treatment of the results that emerged from the instrument, following the procedures described above. The outcome was represented through four semantic networks, which are presented in detail in the following section.

5. Results

Based on the analysis of each imaginary, the following section presents the narrative constructed from the processes of coding, definition of attributes, central themes, and descriptive categories that led to the formulation of semantic postulates. The findings presented below emerge from the analysis of narratives collected in interviews with the fifteen participating professors and reflect shared trends and meanings regarding university virtual education. This qualitative interpretation makes it possible to understand how teachers’ experiences and perceptions shaped the semantic networks displayed in the subsequent figures, integrating personal, institutional, and pedagogical dimensions of their practice.

In the case of the imaginary being a teacher and their training, the narratives revealed a shared view among participants that teacher education is a continuous process demanding ongoing professional growth aligned with the changes required to improve educational quality. As expressed by P6-GFP: “I consider it my responsibility to maintain continuous training that allows me to respond to the challenges posed by education in these contexts and modalities…”

This perspective underscores the need to transform teaching and learning environments, as well as to adopt innovative pedagogical strategies and methods that facilitate the achievement of educational objectives. Participants also emphasized the importance of strengthening their competencies and skills for teaching in modalities other than face-to-face education. In this regard, P3-GFP stated: “as education makes greater use of technology, I have tried to constantly update and prepare myself to respond appropriately to my classes and to students’ training”. This involves a deliberate investment of time in strengthening their technopedagogical and technological competencies.

As one teacher expressed: “You never stop learning; every course, every technological challenge changes the way you teach—and the way you see yourself as a teacher.” (P3)

Similarly, another participant noted: “Teacher education cannot remain only at the technical level; we must also learn how to teach in virtual settings, to reach students through another language” (P7). These voices reflect a conception of teacher education that transcends mere technical training and moves toward the continuous transformation of teaching practice.

Based on these insights, the semantic network shown in

Figure 2 was constructed.

Figure 2.

Semantic network with the representation of the imaginary being a teacher and its training.

Figure 2.

Semantic network with the representation of the imaginary being a teacher and its training.

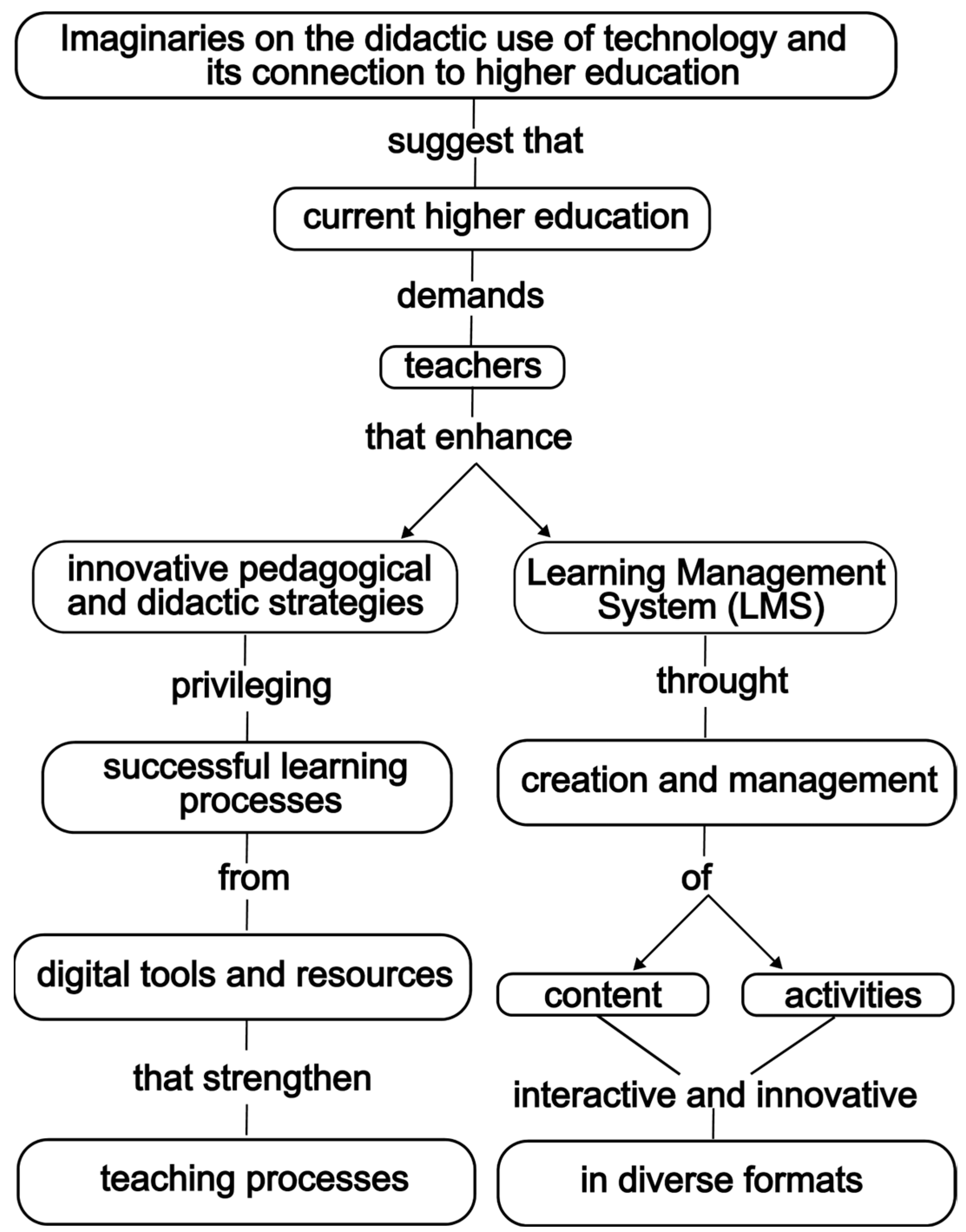

Regarding the imaginary of the didactic use of technology and its connection to Higher Education, teachers consider that contemporary higher education requires the adoption of innovative pedagogical and didactic strategies that enhance student learning. As P2-GFP noted: “I like to research new didactic alternatives offered by digital contexts to strengthen students’ motivation”. They recognize the existence of a wide range of digital tools and resources that enrich teaching in virtual environments.

According to their reflections, this is achieved when teachers understand and apply these strategies through the creation and management of interactive and creative content in different formats, as well as by designing activities that foster student engagement and motivation through Learning Management Systems (LMS). As P13-GFP explained: “The university provides extensive training in our Extended Classroom platform, and in other courses, I’ve worked with Google Classroom and Canvas. That strengthens us as teachers.” However, it is important to clarify that the degree of autonomy teachers have in managing content on these platforms varies depending on the institution, as some allow greater freedom to develop courses using materials, they deem necessary.

Figure 3 presents the semantic network emerging from teachers’ reflections on the imaginary of the didactic use of technology and its connection to Higher Education.

Figure 3.

Semantic network with the representation of the imaginary didactic use of technology and its connection to Higher Education.

Figure 3.

Semantic network with the representation of the imaginary didactic use of technology and its connection to Higher Education.

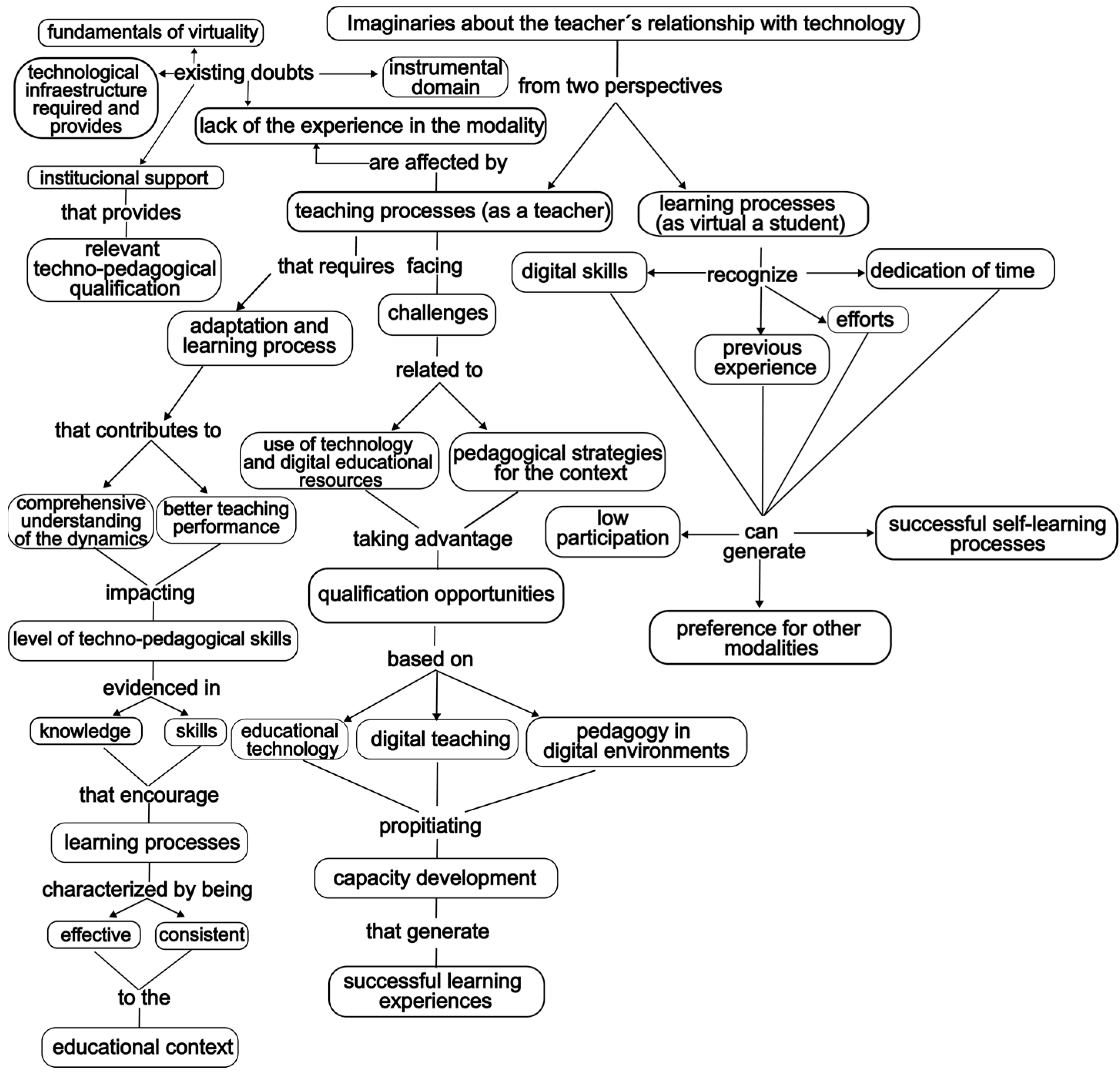

Concerning the imaginary teachers’ relationship with technology, participants indicated that virtual higher education is in constant evolution and requires teachers to face challenges related to both technological proficiency and pedagogical strategies suitable for this context. As expressed by P14-GFP: “I know that to teach in virtual courses I must continue strengthening my technological and pedagogical skills in these virtual environments”. Many teachers stated that, due to a lack of experience in this modality, they experience doubts and uncertainties regarding institutional support, technological infrastructure, and their mastery of digital tools. However, they emphasized that these uncertainties do not reflect rejection, but rather a need for adaptation and learning to perform effectively in virtual settings. As one interviewee mentioned: “Sometimes technology overwhelms me, but when I manage to master it, I feel that I can connect better with my students” (P1). Similarly, another teacher added: “There are days when the system fails, and you have to improvise; that also teaches you to be more creative and patient” (P9). These experiences reflect a resilient and growth-oriented stance, where technological challenges become opportunities for professional development. Teachers also recognized that their level of participation in virtual education may be affected by a lack of prior experience or interest, since online education requires dedication and self-learning skills.

For this reason, the development of technopedagogical competencies is seen as essential. Teachers view virtual education as a continuous process of professional updating and improvement, involving a positive attitude toward transforming teaching practices. Hence, they express a need to commit to strengthening their abilities to take advantage of the opportunities and face the challenges presented by technology-mediated teaching.

Figure 4 synthesizes, through a semantic network, the findings related to the imaginary of teachers’ relationship with technology.

Figure 4.

Semantic network with the representation of the imaginary teacher’s relationship with technology.

Figure 4.

Semantic network with the representation of the imaginary teacher’s relationship with technology.

Regarding the imaginary of Quality in Virtual Education, the findings reveal that participants believe both institutional and teacher decisions and actions have a direct impact on the quality of virtual higher education. Therefore, all actors must collaborate to achieve it. As expressed by P11-GFP: “The success of virtual education depends on a joint effort among institutions, teachers, and students—it’s a shared responsibility”. Teachers believe they should actively participate in the continuous improvement of online programs, viewing this responsibility as an integral part of their professional role and commitment to educational quality. From their perspective, this process requires a positive and open attitude toward improvement, exploring both challenges and opportunities in virtual education.

They recognize that under their teaching role, they may encounter both positive and negative experiences in virtual education; however, limitations can be transformed into opportunities to enhance and elevate quality.

In this sense, they consider that schedule flexibility is a characteristic that, if properly managed, can yield more advantages than disadvantages. As P7-GFP expressed: “As a teacher, what I like most about virtual education is the flexibility it offers to organize and manage learning processes. Nowadays, people simply lack time for everything…”. As another participant pointed out: “Quality doesn’t depend only on the platform but on the commitment you put into course design and student follow-up” (P12). Likewise, another teacher emphasized: “The hardest part is maintaining the human connection; that’s where true quality lies—in not losing closeness with students” (P4).

These statements reveal an understanding of educational quality as a relational process, centered on both teacher commitment and the construction of meaningful bonds with students.

This enthusiastic stance may be related to prior experiences with flexibility, a beneficial and essential feature of this modality. Likewise, participants noted that although virtual higher education faces challenges and limitations that may affect quality, the pursuit of continuous improvement highlights its advantages—especially its adaptability to personal and professional schedules and its capacity to provide inclusive and accessible education that meets the changing needs of students.

To conclude the presentation of results,

Figure 5 presents the semantic networks constructed from the analysis of the imaginary of Quality in Virtual Education.

Figure 5.

Semantic network with the representation of the imaginary quality in virtual education.

Figure 5.

Semantic network with the representation of the imaginary quality in virtual education.

6. Discussion

6.1. Teaching Commitment and Educational Transformation in Digital Settings

The transformation of the contemporary university context, driven by the rise in virtual and blended education, has highlighted the need for university teachers to assume their role with a renewed commitment to pedagogical and technological updating. This is not merely about incorporating digital tools but about reformulating their professional practice from a critical understanding of technology-mediated learning environments.

According to

Revuelta Domínguez et al. (

2022), digital teaching competence is a complex construct that requires the integration of knowledge, skills, and pedagogical attitudes across multiple dimensions. In this sense,

Tondeur et al. (

2023) suggest “four dimensions of teachers’ digital competencies: teaching practice, empowering students for a digital society, teachers’ digital literacy, and teachers’ professional development”.

In this process, self-training capacity emerges as an essential competence for both teachers and students, who must operate in dynamic contexts that demand adaptive skills, autonomy, and innovative thinking.

Beyond the fulfillment of operational tasks, the participating teachers demonstrated a tendency to perceive themselves as active agents in the construction of digitally supported educational experiences. Their narratives revealed motivation to explore methodologies such as microlearning, as well as to create digital resources that promote participation and meaningful learning. Nevertheless, there is still a concentration on the use of conventional platforms such as Moodle, which indicates a gap in the diversification of digital environments and techno-pedagogical strategies.

This presents a challenge not only in terms of training but also in terms of institutional openness to more flexible models that promote experimentation, autonomous design, and pedagogical trial in various virtual scenarios. Thus, teachers’ interest in innovation is confronted by the need for supportive structures that enable the expansion of horizons regarding tools, methodologies, and teaching models.

Furthermore, in this group of teachers, the intention to strengthen their own digital competencies is accompanied by the purpose of shaping their students as active subjects in the use of technology—promoting autonomy and participation in virtual environments. The teaching body not only seeks to consolidate its digital competencies but also expresses a clear intention to empower students as active users of technology.

This formative dimension is reflected in the intention to transcend the traditional role of the teacher and become a facilitator of processes in which students can create content, develop critical skills, and become digital prosumers. In this regard, higher education faces a crucial challenge: to ensure that institutional conditions favor a situated pedagogical practice—conscious of context and capable of engaging with contemporary demands. This involves recognizing teachers as strategic actors in educational transformation, not only from an instrumental standpoint but also from ethical, reflective, and creative perspectives.

6.2. Adaptation to Contemporary Education

The interviewed teachers acknowledge that technology permeates their daily lives and transforms educational dynamics, particularly in the teaching-learning process. According to

Nikou and Aavakare (

2021), the “selection of the relevant digital technology and harmonizing it with the overall teaching and learning strategy is crucial for universities in order to reap the full benefits of emerging technologies”.

The emergence of virtual and blended learning modalities has created new horizons for teacher qualification, strengthening digital teaching competencies. This shift has been positively received by much of the teaching staff, as technology is viewed as a strategic ally in transforming teaching and learning processes. In this regard, technological advancement also entails a transformation in the commitments and responsibilities of the teaching role, requiring ongoing qualification processes aligned with environmental dynamics and student expectations.

Although many teachers come from traditional, face-to-face trajectories, there is an increasing willingness among them to integrate technological mediations into their practice. This openness not only indicates a paradigm shift but also legitimizes institutional efforts to support such transitions through situated pedagogical approaches.

The willingness to explore new educational scenarios aligns with professional development programs designed to strengthen teaching practice in digital environments, suggesting that initiatives led by Pedagogy Departments respond largely to the real interests of faculty members. Consequently, institutions can design more effective training programs that address teachers’ specific needs. This, in turn, will lead to improved teaching practices and student outcomes, as faculty members become better equipped to integrate digital tools into their pedagogy, as stated by

Moreira-Choez et al. (

2024).

Interest in training within virtual environments also transcends the instrumental logic, becoming a reflective process in which the teacher assumes the role of a learner. This formative experience not only enables the appropriation of digital skills but also exposes teachers to challenges commonly faced by virtual students—such as time management, balancing professional and academic responsibilities, and establishing personal learning rhythms. Rather than obstacles, these experiences become valuable inputs for rethinking the relationship between pedagogical design and the real-life conditions of educational actors.

Within this logic, the limits identified in virtual training experiences—such as lack of time or limited face-to-face qualification opportunities—are not viewed solely as individual shortcomings but as opportunities to redesign more inclusive institutional policies.

It becomes evident that a significant portion of faculty members still do not feel fully prepared to perform their roles in technology-mediated environments, reaffirming the need for continuous, flexible, and teacher-centered professional development programs. These transformations represent a turning point for universities, which must rethink traditional models of teacher development from a critical and situated perspective.

According to

Karimi and Khawaja (

2025), “the digital transformation of the education sector has placed increasing demands on university teachers to develop and apply robust digital competencies in their teaching practices”. This transition toward technology-mediated educational models requires not only technical skills but also a profound reconfiguration of the pedagogical meaning of teaching.

Digital competence should not be limited to the ability to use tools; it must also be oriented toward a critical understanding of their ethical, social, and formative implications. In this sense, the university is called to become a space for care and collective construction of digital knowledge, where teachers are not merely platform operators but designers of situated, equitable, and transformative learning experiences.

6.3. Quality in Virtual Education: A Constant Commitment to Innovative Learning Environments

Educational quality in virtual environments depends on institutional will and teacher commitment to generating meaningful learning experiences. When institutions and teachers engage actively, a collaborative synergy emerges that supports the continuous development of digital competencies and the effective use of digital platforms.

According to

Tuero et al. (

2023), in these spaces, the sustained improvement of virtual teaching becomes a shared responsibility, allowing teachers to adopt innovative pedagogical methods aligned with the demands of the digital context.

For teachers, their role goes beyond delivering classes: their influence extends to dimensions such as student retention and dropout—key elements in current debates on educational quality. The continuous renewal of their pedagogical practice enables the design of memorable learning experiences that foster motivation and belonging. As

Sharif et al. (

2025) affirm, this approach goes beyond digital content, focusing on the construction of authentic connections that encourage educational continuity.

Moreover, inclusion and flexibility stand as pillars of institutional quality: by offering learning without geographical or temporal constraints, diverse needs are addressed and democratized education is promoted. This openness facilitates access to learning environments adapted to students’ changing realities, enhancing equity and reducing barriers.

Thus, virtual education represents not only a challenge but also an opportunity to rethink educational quality through inclusive, student-centered practices.

6.4. Interpretive Synthesis: Cartography of Subjectivities

The cartography of subjectivities derived from the analysis of semantic networks (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) integrates the institutional, personal, and pedagogical dimensions that shape the teaching experience in virtual education. In the analyzed narratives, these dimensions intertwine, forming a symbolic fabric in which teacher education, the didactic use of technology, relationships with the digital world, and perceptions of quality emerge as interdependent expressions of the same meaning-making process. Tensions arise particularly at the intersections between institutional demands for innovation and personal insecurities regarding technological mastery, as well as between the desire for educational quality and the structural limitations inherent to the university context.

This articulated reading allows for an understanding of how teachers’ social imaginaries configure a collective symbolic structure from which they construct their sense of practice and professional identity in the virtual university environment.

Furthermore, the evaluation of quality in virtual education must incorporate multidimensional frameworks that account for both quantitative indicators—such as completion rates and academic performance—and qualitative dimensions, including student satisfaction, engagement, and perceived relevance of the learning experience. As

Anderson et al. (

2020) affirm, holistic assessment models not only provide a richer understanding of educational effectiveness but also guide strategic decisions regarding curriculum design, instructional support, and technological infrastructure.

In this context, fostering a culture of feedback and reflective practice becomes essential. Encouraging faculty to engage in critical self-assessment and peer review contributes to the refinement of teaching strategies and supports adaptive responses to emerging challenges. Institutions that cultivate these reflective ecosystems are better positioned to promote pedagogical innovation and sustain quality standards in virtual education over time.

Ultimately, achieving and sustaining quality in virtual education entails a profound cultural transformation within higher education institutions—one that moves beyond the mere adoption of digital tools toward the intentional design of pedagogical ecosystems that are inclusive, adaptive, and evidence-informed. Such transformation calls for leadership committed to fostering reflective teaching practices, promoting experimentation, and valuing the voices and lived experiences of educators and students alike. It also involves continuous dialogue between institutional policies and pedagogical realities to ensure that evaluation metrics, professional development, and infrastructure are aligned with the goal of meaningful, student-centered learning.

In this regard, quality is not a static achievement but an evolving commitment that demands responsiveness to technological change, social diversity, and epistemological pluralism. Faculty must be supported not only in acquiring technical competencies but also in developing critical digital literacies that enable them to interrogate the implications of virtual education and co-construct learning environments that are equitable, participatory, and transformative. Only by embedding innovation within a robust ethical and pedagogical framework can institutions ensure that virtual education fulfills its promise as a vehicle for expanding access, deepening engagement, and enhancing the overall quality of higher learning in the digital age.

7. Conclusions and Suggestions for Practical Use

The experience gathered in institutions such as Universidad Simón Bolívar, Cúcuta campus, highlights how timely and continuous institutional support becomes a key pillar in fostering technological appropriation from a meaningful pedagogical perspective. This approach transcends teacher training frameworks and impacts the learning processes of university students.

At the institutional level, discourses emerge that guide teacher education and practice within regulatory and programmatic frameworks defined by the university under study. These discourses, present in documents such as the Institutional Educational Plan, the Teacher Training Policy, and the Virtual Education Guidelines, promote a professorial ideal associated with pedagogical innovation, research, and social responsibility.

However, the narratives of participating teachers reveal that these institutional directives do not always materialize in everyday practices, generating a field of tension between the institutional ought-to-be and the subjective experience of being a teacher. This distance exposes the complexity of the link between the normative and the lived dimensions, reinforcing the interpretation of the coexistence of institutional and personal imaginaries in university teaching practice.

The findings of this study offer a situated panorama shaped by the voices of participating teachers, who—through their imaginaries and lived experiences—reveal the richness and complexity of a learning environment that, while distinct from face-to-face education, engages in dialogue with national and international transformations in the field of virtual education.

This research provides a global perspective grounded in the voices of those responsible for educating future professionals. Through their perspectives—beyond the direct impositions of pedagogy, didactics, and technological structures within institutions—teachers have made visible, through their imaginaries, the richness of a learning context unfamiliar to many, yet clearly aligned with national and global trends in education modalities. This opens up diverse possibilities for rethinking the structure of teacher qualification programs offered by institutions, aimed at supporting this transformation—not only of pedagogical and didactic practices in virtual contexts but also of the paradigms deeply embedded within this population.

Based on this experience, it is suggested that higher education institutions promote similar exercises of inquiry into teachers’ imaginaries. From this study, it is recommended that universities implement initiatives that explore faculty imaginaries in order to understand their stances and obtain a contextualized diagnosis of their relationship with technology, their training processes, uncertainties, intentions, and expectations regarding the professional development programs offered by their institutions.

Furthermore, the design of qualification processes must not be disconnected from the structural conditions of teaching practice. The tensions between administrative demands, academic commitments, and personal life have created scenarios of overload that, if not recognized and addressed, may limit any intention of innovation. In this context, it is urgent to promote institutional policies that integrate continuous professional development as a labor right, ensuring time, resources, and sustainable support for teachers’ professional growth.

This study was conducted with a group of 15 teachers from a single higher education institution; therefore, the findings are not intended to be statistically generalizable. However, from a qualitative and interpretive perspective, the results can be transferable to educational contexts that share similar structural, organizational, and cultural characteristics. The configurations of teaching imaginaries described herein should be understood in light of the institutional specificities and symbolic frameworks of the university under study.

Future research could broaden this perspective by comparing different university contexts—both national and international—to explore how institutional policies, academic cultures, and training processes shape the experiences and imaginaries of being a teacher in diverse ways.

Overall, the challenges and opportunities of virtual education demand a profound redefinition of the teaching role and of the institutional conditions that ensure quality. Beyond the mere incorporation of technologies, the goal is to cultivate an innovative, flexible, and inclusive pedagogical culture that places the student at the center of the learning process.

The creation of disruptive and memorable learning environments requires commitment, continuous professional development, and openness to change on the part of teachers, as well as institutional policies that support mentoring, reflective evaluation, and the sustainability of good educational practices in digital environments. Only through such means will it be possible to consolidate virtual education with quality standards comparable to—or even surpassing—those of traditional models.

In this regard, the results presented here do not aim to establish generalizations but rather to offer a situated and transferable understanding of the meanings that university teachers attribute to virtual education. These interpretations contribute to broadening the reflection on teacher training and institutional management in digital settings, providing valuable insights to strengthen teaching and learning processes in contemporary higher education.

Limitations

While the findings provide an in-depth understanding of the representations and meanings constructed by the participating teachers, they must be interpreted as contextually situated results within the specific environment of University Simon Bolivar.

This study was based on the narratives of fifteen professors, which limits the possibility of generalizing the results to other institutional settings. Nevertheless, the qualitative richness of the data and the use of grounded theory enhance the transferability of the findings to contexts with similar characteristics, offering valuable insights into the teaching experience in university virtual education.