Teachers’ Participation in Digitalization-Related Professional Development: An International Comparison

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. National Contexts for the Use of ICT in Schools

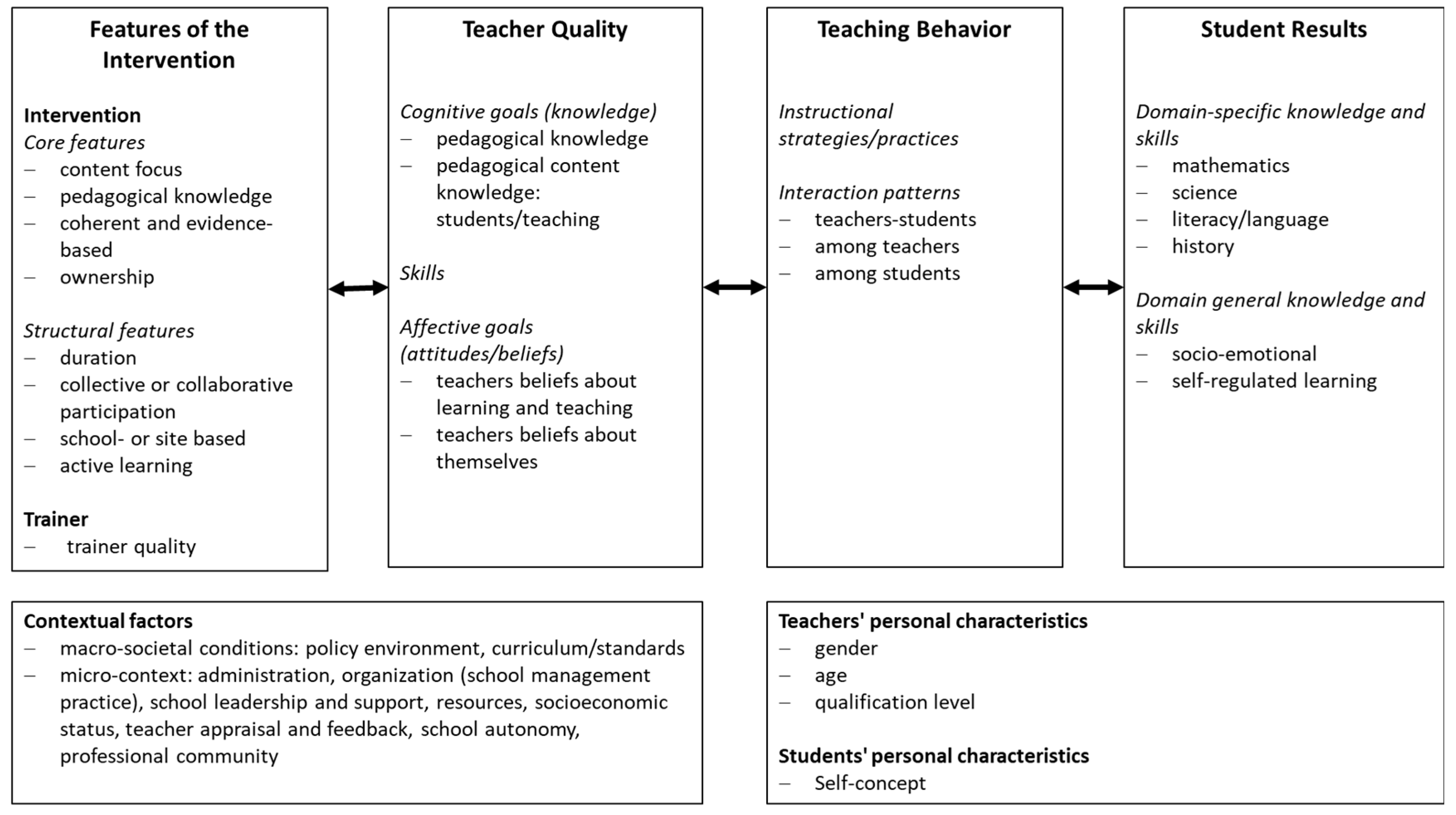

3. Extended Evaluative Framework for Mapping the Effects of Professional Development Initiatives

4. Participation in Professional Development Activities: Numbers, Requirements, and Obstacles

5. Effects of Professional Development Activities

6. Objectives and Research Questions

7. Materials and Methods

7.1. Data Basis

7.2. Instruments and Operationalization

7.3. Methodical Approach

8. Results

8.1. Participation in Digitalization-Related Professional Development

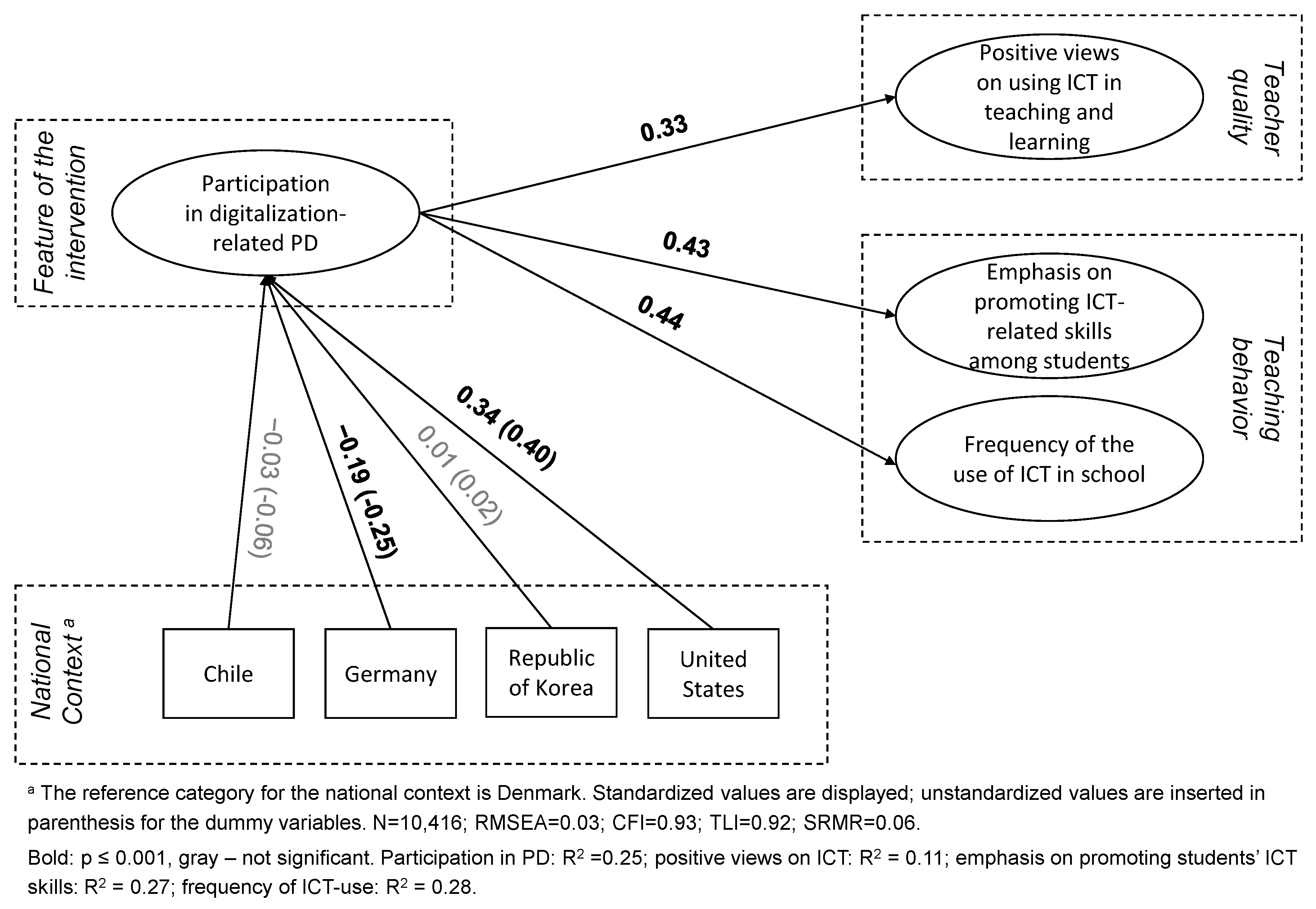

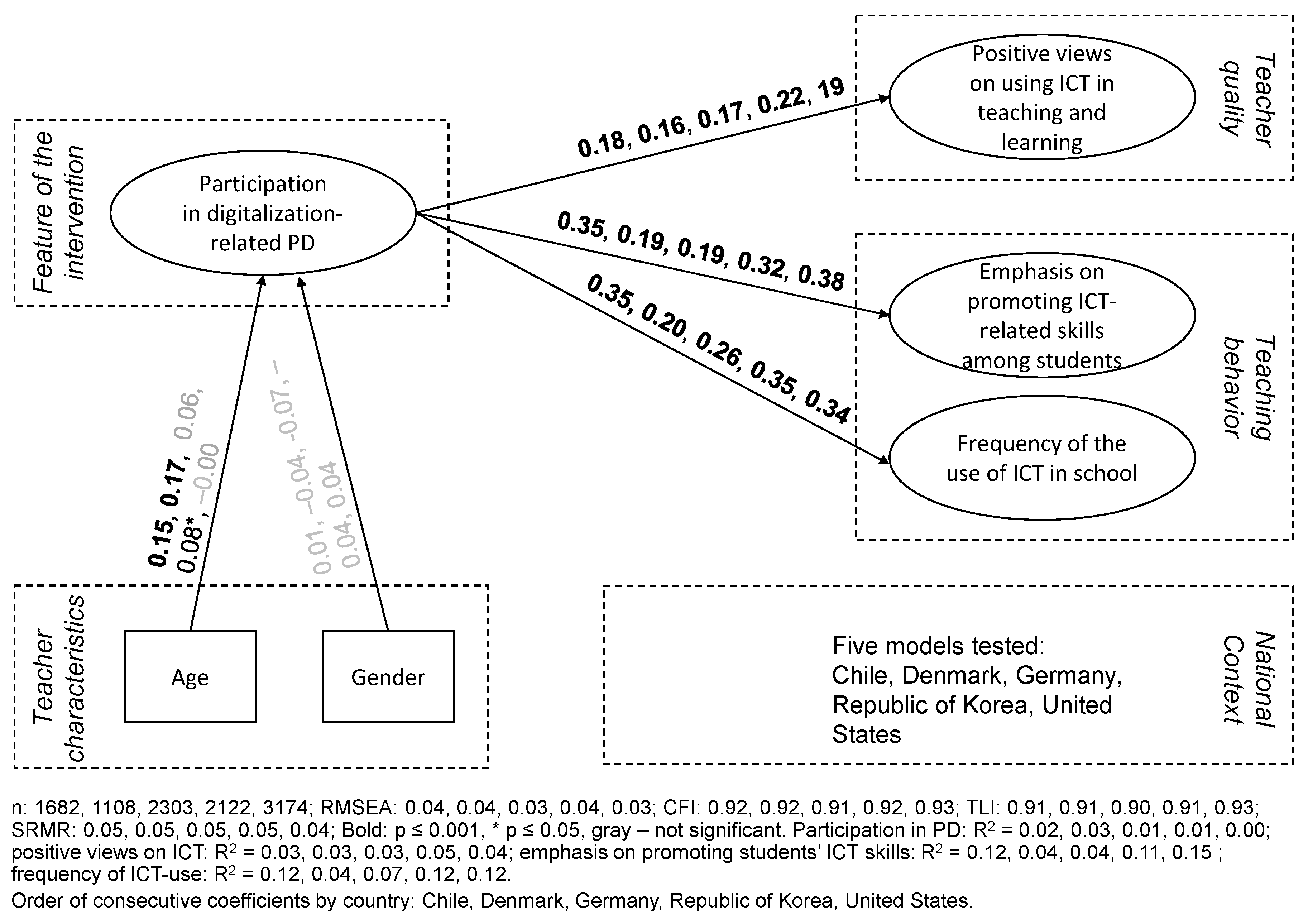

8.2. Impact of Teachers’ Participation in Digitalization-Related Professional Development

9. Discussion

9.1. Summary and Classification of the Results

9.2. Implications, Limitations, and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Teachers’ digital competence is an evolving concept, described in different terms and encompassing a variety of different skills and competencies (Ilomäki et al., 2016). In an overview of conceptualizations in the literature, Skantz-Åberg et al. (2022) find seven recurring aspects of teachers’ professional digital competence: technological competence, content knowledge, attitudes to technology use, pedagogical competence, cultural awareness, critical approach, and professional engagement. |

| 2 | The participating countries of ICILS 2018 were Chile, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Kazakhstan, Korea, Luxembourg, Portugal, the United States, and Uruguay. On top, Moscow (Russian Federation) and North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany) were benchmarking participants who only took part in the study with individual regions, cities, or provinces of a country. North Rhine-Westphalia is unique in that it participated both as a region of Germany and as part of the German sample with an oversampling of 80 additional schools (Fraillon et al., 2020). The sample criteria for the teacher survey was a weighted overall participation rate of 75 percent, which in Denmark, Kazakhstan, France, and the USA was only met after the incorporation of replacement schools (Fraillon et al., 2020). |

| 3 | In an international comparison, only the simple index T_AGE from ICILS 2018 is available. The approximate age of teachers is used here. The following simple recoding was performed: less than 25 = 23; 25–29 = 27; 30–39 = 35; 40–49 = 45; 50–59 = 55; and 60 or over = 63 (Mikheeva & Meyer, 2020, p. 64). |

References

- Albion, P. R., Tondeur, J., Forkosh-Baruch, A., & Peeraer, J. (2015). Teachers’ professional development for ICT integration: Towards a reciprocal relationship between research and practice. Education and Information Technologies, 20(4), 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerup, P., Kirkegaard, S., Belling, M. N., & Stafseth, V. T. (2016). Denmark. In I. V. S. Mullis, M. O. Martin, S. Goh, & K. Cotter (Eds.), TIMSS 2015 encyclopedia: Education policy and curriculum in mathematics and science. ICS. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y. (2018). The effects of an online professional development course on teachers’ perceptions, attitudes, self-efficacy, and behavioral intentions regarding digital game-based learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(6), 1505–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in Teaching and Teacher Education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, A., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2015). Teacher professional development: International perspectives and approaches. Pschology, Society, & Education, 7(3), 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, S. (2018). Evaluating the impact of professional development. RELC Journal, 49(2), 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dağ, F. (2016). Examination of the professional development studies for the development of technological competence of teachers in Turkey in the context of lifelong learning. Yaşam boyu öğrenme bağlamında Türkiye’de öğretmenlerin teknolojik yeterliliklerinin geliştirilmesine yönelik mesleki gelişim çalışmalarının incelenmesi. International Journal of Human Sciences, 13(1), 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., Gardner, M., & Espinoza, D. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone, L. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossel, K., & Eickelmann, B. (2017). Teachers’ participation in professional development concerning the implementation of new technologies in class: A latent class analysis of teachers and the relationship with the use of computers, ICT self-efficacy and emphasis on teaching ICT skills. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 5(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossel, K., Eickelmann, B., & Gerick, J. (2016). Predictors of teachers’ use of ICT in school—The relevance of school characteristics, teachers’ attitudes and teacher collaboration. Education and Information Technologies, 22(2), 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve-Mon, F. M., Llopis-Nebot, M. A., & Adell-Segura, J. (2020). Digital teaching competence of university teachers: A systematic review of the literature. IEEE Revista Iberoamericana De Tecnologias Del Aprendizaje, 15(4), 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2013). Survey of schools: ICT in Education: Benchmarking access, use and attitudes to technology in Europe’s schools: Final report: A study prepared for the European Commission DG communications networks, content & technology. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2019). 2nd survey of schools: ICT in education: Objective 1: Benchmark progress in ICT in schools, final report. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2023). Education and training monitor 2023: Comparative report. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernández-Cerero, J., & García-Martínez, I. (2022). Digital competences for teacher professional development. Systematic review. European Journal of Teacher Education, 45(4), 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraillon, J., Ainley, J., Schulz, W., Friedman, T., & Duckworth, D. (2020). Preparing for life in a digital world: Iea international computer and information literacy study 2018 international report (1st ed.). Springer eBook Collection. Springer International Publishing; Imprint Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEW Deutschland. (2009). Wirksame Lehr-und Lernumgebungen schaffen. Gewerkschaft für Erziehung und Wissenschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, M. S., & Wagner, R. (2020). The impact of missing values on PLS, ML and FIML model fit (Vol. 6). KIT Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, G. B., & Hatlevik, O. E. (2018). Newly qualified teachers’ professional digital competence: Implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggemos, J., & Seufert, S. (2021). Teaching with and teaching about technology—Evidence for professional development of in-service teachers. Computers in Human Behavior, 115, 106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Haixia, L., Koehler, M., & Wang, L. (2018). The impacot of teachers’ beliefs on their different uses of technology. South China Institute of Software Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- Hardré, P. L., Ling, C., Shehab, R. L., Herron, J., Nanny, M. A., Nollert, M. U., Refai, H., Ramseyer, C., & Wollega, E. D. (2014). Designing and evaluating a STEM teacher learning opportunity in the research university. Evaluation and Program Planning, 43, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, R., Tondeur, J., van Braak, J., & Valcke, M. (2008). The impact of primary school teachers’ educational beliefs on the classroom use of computers. Computers & Education, 51(4), 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., Ma, J., & Yang, J. (2021). What to teach? Strategies for developing digital competency in preservice teacher training. Computers & Education, 165, 104149. [Google Scholar]

- Ilomäki, L., Paavola, S., Lakkala, M., & Kantosalo, A. (2016). Digital competence—An emergent boundary concept for policy and educational research. Education and Information Technologies, 21(3), 655–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, E., Kahlert, J., & Haag, L. (2014). Was ist ein guter Fall für die Aus-und Weiterbildung von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern? Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen-und Lehrerbildung, 32(1), 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Methodology in the social sciences. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, J. H. L., Chai, C. S., & Lim, W. Y. (2017). Teacher professional development for TPACK-21CL. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 55(2), 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschel, J., Richter, D., & Lazarides, R. (2020). Wie relevant ist die gesetzliche Fortbildungsverpflichtung für Lehrkräfte? Eine empirische Untersuchung zur Fortbildungsteilnahme in verschiedenen deutschen Bundesländern. Zeitschrift Für Bildungsforschung, 10(2), 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O., Choi, E., Griffiths, M., Goodyear, V., Armour, K., Son, H., & Jung, H. (2019). Landscape of secondary physical education teachers’ professional development in South Korea. Sport, Education and Society, 24(6), 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods, 48(3), 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, V. A., Ramírez-Correa, P. E., & Grandón, E. E. (2019). Innovativeness and factors that affect the information technology adoption in the classroom by primary teachers in Chile. Informatics in Education, 18(1), 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M., Dorotea, N., & Piedade, J. (2021). Developing teachers’ digital competence: Results from a pilot in Portugal. IEEE Revista Iberoamericana De Tecnologias Del Aprendizaje, 16(1), 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malley, L., Neidorf, T., Arora, A., & Kroeger, T. (2016). United States. In I. V. S. Mullis, M. O. Martin, S. Goh, & K. Cotter (Eds.), TIMSS 2015 Encyclopedia: Education Policy and Curriculum in Mathematics and Science. ICS. [Google Scholar]

- Mannila, L., Nordén, L.-Å., & Pears, A. (2018, August 13–15). Digital competence, teacher self-efficacy and training needs. Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research (ACM Conferences), Espoo, Finland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss. (2020). DigitalPakt Schule und Digitalisierung an Schulen: Ergebnisse einer GEW-Mitgliederbefragung und Wissenschaft (GEW). Mauss Research. [Google Scholar]

- Merchie, E., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., & Vanderlinde, R. (2018). Evaluating teachers’ professional development initiatives: Towards an extended evaluative framework. Research Papers in Education, 33(2), 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheeva, E., & Meyer, S. (Eds.). (2020). IEA international computer and information literacy study 2018: User guide for the international database. IEA Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Njenga, M. (2023). Teacher participation in continuing professional development: A theoretical framework. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 29(1), 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2009). Creating effective teaching and learning environments: First results from TALIS. (1. Aufl.). OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2015). Students, computers and learning: Making the connection. (Rev. version). OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2016). PISA 2015 results. PISA. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 Results. Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners: Volume I. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2022). Education at a Glance 2022: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsakdi, N., Kortelainen, A., & Veermans, M. (2021). The impact of digital pedagogy training on in-service teachers’ attitudes towards digital technologies. Education and Information Technologies, 26(5), 5041–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestridge, S. (2010). ICT professional development for teachers in online forums: Analysing the role of discussion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(2), 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, A. A. A., & Viswanathappa, G. (2016). Teacher perceptions towards ICT Integration: Professional development through blended learning. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 15, 561–575. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.-S., Mena, J., & Rodríguez-Arroyo, J. A. (2017). In-service teachers’ self-perceptions of digital competence and OER use as determined by a xMOOC training course. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redecker, C. (2017). European framework for the digital competence of educators: Digcompedu. Publications Office. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisoğlu, İ. (2022). How does digital competence training affect teachers’ professional development and activities? Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 27(3), 721–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, D., Kunter, M., Anders, Y., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2010). Inhalte und Prädiktoren beruflicher Fortbildung von Mathematiklehrkräften. Empirische Pädagogik, 24(2), 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, D., Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2011). Professional development across the teaching career: Teachers’ uptake of formal and informal learning opportunities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Moreno, J., Agreda Montoro, M., & Ortiz Colón, A. (2019). Changes in teacher training within the TPACK model framework: A systematic review. Sustainability, 11(7), 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, I., Lazarides, R., Rubach, C., & Richter, D. (2022a). Unterrichtsqualität und digitale Medien: Welche Bedeutung haben Lehrkräftefortbildung und-kooperation sowie motivationale Überzeugungen? Empirische Pädagogik, 36(2), 166–184. [Google Scholar]

- Runge, I., Rubach, C., & Lazarides, R. (2022b). Selbsteingeschätzte digitale Kompetenzen von Lehrkräften: Welche Bedeutung haben Schulausstattung und Fortbildungsteilnahme angesichts aktueller Herausforderungen der COVID-19 Pandemie? Jahrbuch Schulleitung. [Google Scholar]

- Sancar, R., Atal, D., & Deryakulu, D. (2021). A new framework for teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 101, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skantz-Åberg, E., Lantz-Andersson, A., Lundin, M., & Williams, P. (2022). Teachers’ professional digital competence: An overview of conceptualisations in the literature. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2063224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, L. (2020). A review of research exploring teacher preparation for the digital age. Cambridge Journal of Education, 50(1), 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stürmer, K., & Seidel, T. (2017). Connecting generic pedagocial knowledge with practice. In S. Guerriero, & OECD (Eds.), Educational research and innovation. Pedagogical knowledge and the changing nature of the teaching profession (pp. 137–149). OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Thurm, D. (2020). Digitale Werkzeuge im Mathematikunterricht integrieren: Zur Rolle von Lehrerüberzeugungen und der Wirksamkeit von Fortbildungen. Essener Beiträge zur Mathematikdidaktik. [XVII, 413 Seiten]. Springer Spektrum. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieck, S., & Meinck, S. (2020). Weights and variance estimation for ICILS 2018. In E. Mikheeva, & S. Meyer (Eds.), IEA international computer and information literacy study 2018: User guide for the international database (pp. 25–38). IEA Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2018). Ict competency framework for teachers: Version 3. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Waffner, B. (2020). Unterrichtspraktiken, Erfahrungen und Einstellungen von Lehrpersonen zu digitalen Medien in der Schule. In A. Wilmers, C. Anda, C. Keller, & M. Rittberger (Eds.), Digitalisierung in der Bildung: Band 1. Bildung im digitalen Wandel: Die Bedeutung für das pädagogische Personal und für die Aus-und Fortbildung (pp. 57–102). Waxmann. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, G. (2014). Understanding and creating CPD for and with teachers; the development and implementation of a model for CPD [Doctoral dissertation, Newcastle University]. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, H., Smith, D. S., & Bos, W. (2016). Germany. In I. V. S. Mullis, M. O. Martin, S. Goh, & K. Cotter (Eds.), TIMSS 2015 Encyclopedia: Education Policy and Curriculum in Mathematics and Science. ICS. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfart, O., & Wagner, I. (2023). Teachers’ role in digitalizing education: An umbrella review. Educational Technology Research and Development: ETR & D, 71(2), 339–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., & Yang, Y. (2019). Rmsea, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | Chile | Denmark | Germany | Republic of Korea | USA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To improve ICT/technical skills | ● ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ● ∆ ◊ |

| To improve content knowledge with respect to computer information literacy (CIL) | ● ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ● ∆ ◊ |

| To improve teaching skills with respect to CIL-related content | ● ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ● ∆ ◊ |

| To develop digital teaching and learning resources | ● ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ∆ |

| To integrate ICT in teaching and learning activities | ● ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ● ∆ |

| To improve skills in computer programming or developing applications for digital devices | ● ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ∆ | ● ∆ ◊ | ● ∆ |

| Chile | Denmark | Germany | Republic of Korea | USA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | N = 1682 | N = 1108 | N = 2303 | N = 2122 | N = 3174 |

| Sex/Gender | |||||

| Female | 60.64% | 59.12% | 61.09% | 66.07% | 67.77% |

| Male | 39.36% | 40.88% | 38.91% | 33.93% | 32.23% |

| Age in Years (Mean) | 40.02 | 45.32 | 45.33 | 43.99 | 42.66 |

| Construct | Items | α |

|---|---|---|

| Participation in structured-learning PD related to ICT | How often have you participated in any of the following professional learning activities in the past two years? 5 items, e.g., a course on how to use ICT to support personalized learning by students. 1—Not at all; 2—Once only; 3—More than once. | 0.84 |

| Positive views on using ICT in teaching and learning | To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following practices and principles in relation to the use of ICT in teaching and learning? Using ICT at school: 6 items, e.g., improves academic performance of students. 1—Strongly disagree; 2—Disagree; 3—Agree; 4—Strongly Agree. | 0.86 |

| Use of ICT for teaching practices in class | How often do you use ICT in the following practices when teaching your reference class? 8 items, e.g., the provision of feedback to students on their work. 1—I never use ICT with this practice; 2—I sometimes use ICT with this practice; 3—I often use ICT with this practice; 4—I always use ICT with this practice. | 0.92 |

| Emphasis on developing students CIL | In your teaching the reference class in this school year, how much emphasis have you given to developing the following ICT-based capabilities in your students? 9 items, e.g., to access information efficiently. 1—No emphasis; 2—Little emphasis; 3—Some emphasis; 4—Strong emphasis. | 0.93 |

| Participation of Teachers | Chile | Denmark | Germany | Republic of Korea | USA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A course on ICT applications (e.g., word processing, presentations, internet use, spreadsheets, databases) | Never | 51.86 (2.09) | 72.06 (1.93) | 73.85 (1.74) | 56.08 (2.48) | 37.43 (1.42) |

| Once | 27.11 (1.75) | 16.80 (1.75) | 17.76 (1.22) | 30.34 (1.99) | 25.10 (1.13) | |

| More than once | 21.02 (1.84) | 11.14 (1.06) | 8.40 (1.31) | 13.58 (0.87) | 37.47 (1.48) | |

| A course or webinar on integrating ICT into teaching and learning | Never | 63.60 (2.08) | 66.56 (1.73) | 68.53 (2.07) | 50.71 (2.03) | 34.93 (1.33) |

| Once | 23.67 (1.77) | 19.33 (1.36) | 22.77 (1.93) | 33.46 (1.96) | 26.21 (1.53) | |

| More than once | 12.73 (1.47) | 14.10 (1.31) | 8.70 (0.93) | 15.83 (0.85) | 38.86 (1.88) | |

| Training on subject-specific digital teaching and learning resources | Never | 67.91 (1.80) | 45.14 (1.89) | 69.34 (1.83) | 46.98 (2.67) | 29.72 (1.36) |

| Once | 20.16 (1.56) | 32.98 (1.78) | 21.95 (1.71) | 38.25 (2.81) | 27.17 (1.32) | |

| More than once | 11.92 (0.87) | 21.88 (1.53) | 8.71 (1.06) | 14.77 (0.75) | 43.11 (1.86) | |

| A course on use of ICT for students with special needs or specific learning difficulties | Never | 85.69 (1.16) | 63.79 (2.91) | 95.41 (0.86) | 81.61 (1.22) | 66.65 (1.56) |

| Once | 9.34 (0.91) | 24.51 (2.24) | 1.62 (0.38) | 14.37 (1.11) | 18.29 (1.48) | |

| More than once | 4.97 (0.72) | 11.70 (1.35) | 2.97 (0.56) | 4.03 (0.41) | 15.06 (1.00) | |

| A course on how to use ICT to support personalized learning by students | Never | 77.39 (1.51) | 71.03 (2.09) | 77.75 (1.26) | 70.34 (1.22) | 54.28 (1.76) |

| Once | 14.47 (1.36) | 17.28 (1.27) | 14.89 (1.06) | 23.00 (1.21) | 24.92 (1.21) | |

| More than once | 8.15 (1.01) | 11.69 (1.66) | 7.37 (0.93) | 6.66 (0.60) | 20.80 (1.11) |

| Variable | (a) Chile | (b) Denmark | (c) Germany | (d) Republic of Korea | (e) USA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A course on ICT applications | 1.69 b,c,d,e (0.04) | 1.39 a,d,e (0.03) | 1.35 a,d,e (0.03) | 1.58 a,b,c,e (0.03) | 2.00 a,b,c,d (0.03) |

| A course or webinar on integrating ICT into teaching and learning | 1.49 c,d,e (0.03) | 1.48 d,e (0.03) | 1.4 a,d,e (0.03) | 1.65 a,b,c,e (0.02) | 2.04 a,b,c,d (0.03) |

| Training on subject-specific digital teaching and learning resources | 1.44 b,d,e (0.02) | 1.77 a,c,d,e (0.03) | 1.39 b,d,e (0.03) | 1.68 a,b,c,e (0.02) | 2.13 a,b,c,d (0.03) |

| A course on use of ICT for students with special needs or specific learning difficulties | 1.19 b,c,e (0.02) | 1.48 a,c,d (0.04) | 1.08 a,b,d,e (0.01) | 1.22 b,c,e (0.01) | 1.48 a,c,d (0.02) |

| A course on how to use ICT to support personalized learning by students | 1.31 b,d,e (0.02) | 1.41 a,c,e (0.04) | 1.3 b,d,e (0.02) | 1.36 a,c,e (0.01) | 1.67 a,b,c,d (0.03) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Annemann, C.; Menge, C.; Gerick, J. Teachers’ Participation in Digitalization-Related Professional Development: An International Comparison. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040486

Annemann C, Menge C, Gerick J. Teachers’ Participation in Digitalization-Related Professional Development: An International Comparison. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):486. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040486

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnnemann, Christiane, Claudia Menge, and Julia Gerick. 2025. "Teachers’ Participation in Digitalization-Related Professional Development: An International Comparison" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040486

APA StyleAnnemann, C., Menge, C., & Gerick, J. (2025). Teachers’ Participation in Digitalization-Related Professional Development: An International Comparison. Education Sciences, 15(4), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040486