Developing Beginning Design Students’ Self-Directed Learning Through Leadership Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Purpose and Approach

3. Description of Action Research Process

3.1. Institutional Context

3.2. Identifying the Problem: A Checklist Mentality to Learning

4. Gathering Information

4.1. Data from Students

Be more welcoming to ambiguity in the design process. Be more flexible. You need to get used to it.

My interpretation is that you need a checklist to follow in the design process. Well, we all do need and create checklists for most of our daily tasks.

4.2. Reviewing the Literature

4.3. Self-Directed Learning

4.4. Adaptive Leadership

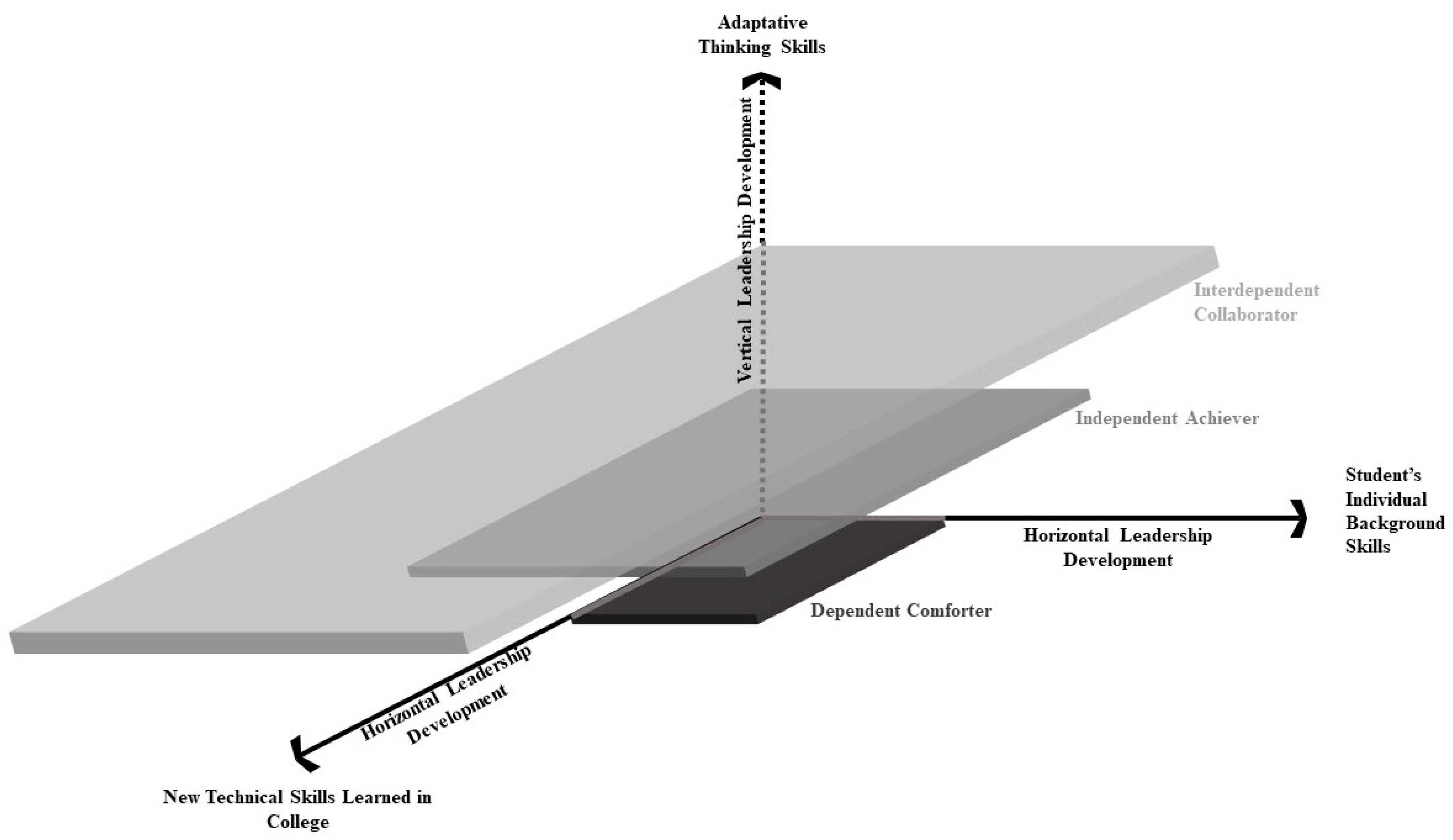

4.5. Vertical Leadership Development

- Heat experience: Confronting a complex situation that disrupts and challenges our usual thought patterns.

- Colliding perspectives: Engaging with individuals holding diverse worldviews and opinions.

- Evaluated sense-making: Employing a structured process to integrate and comprehend various perspectives and experiences.

4.6. Developing and Implementing Research Plan

- Express themselves and develop their mindset, identity, and motivation as designers.

- Take a stand for what they believe in and what matters to them as designers.

- Understand their technical and adaptive challenges to improve as design students.

- Try to find ways that are unique to them to overcome or get better at challenges in the design process.

- Design what they have always cared about and bring their background and cultural aspects to it.

- Become more comfortable with ambiguities during the design process.

- Practice active listening in peer-coaching sessions.

- Drive agendas and lead possible changes for what needs to be done.

4.6.1. Phase 1—Co-Creating a Practical and Attractive Assignment Statement

4.6.2. Phase 2—Diagnosing Survey to Choose Design Topics

- The reasons for which students decided to become designers.

- The things in the design field that mattered to students the most.

- The things they wished to learn in the first-year design studios.

- The technical problems and adaptive challenges they usually face during the design process (O’Malley & Cebula, 2015).

4.6.3. Phase 3—Sharing Feedback and Suggestions in Peer-Coaching Sessions

4.6.4. Phase 4—Design

4.6.5. Phase 5—Reflection

- What did students learn about themselves and/or improve as designers in this exercise?

- What challenges did they face during this project?

- Based on their evaluation, how successful was this project?

5. Data Analysis

6. Findings

6.1. Phase 1—Co-Creating the Assignment

6.2. Phase 2—Diagnosing Survey to Choose Design Topics

6.3. Phase 3—Sharing Feedback and Suggestions in Peer-Coaching Sessions

6.4. Phase 4—Applying Leadership Skills to Start the Design Process

6.4.1. Breaking Conventional Boundaries and Embracing Creativity

6.4.2. Family and Personal Background as Key Influences

6.4.3. Desire to Stand Out and Think Outside the Box

6.4.4. Balancing Technical Mastery with Adaptive Growth

6.5. Phase 5—Students’ Reflections on the Self-Directed Exercise

[I learned that] I like solving problems that I don’t have an obvious answer for; I know how to manage myself; and I know what changes need to be made and when.

It showed me how important the process is and that I need to put all my ideas out, whether good or bad.I learned what changes to make and when.I am in a different mindset of attention to detail.

I thought this project was really fun, and I learned a lot about myself as a designer and a person. I really enjoyed it.I loved this project. It was nice to do something that felt related to what I hope to do with my career. It was hard, but fun.I want to do more projects with more creative freedom, where I can be in control of the entire process.

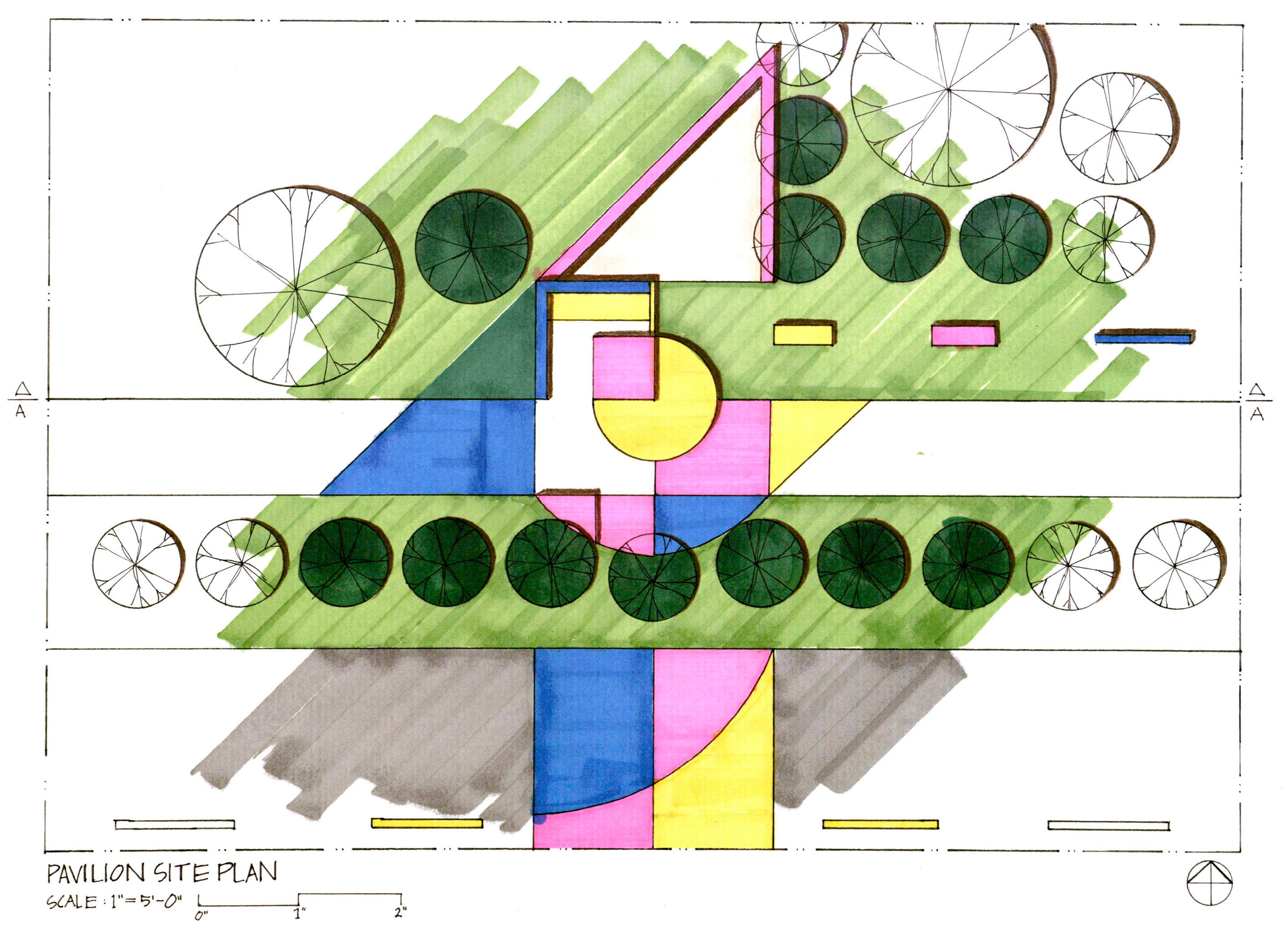

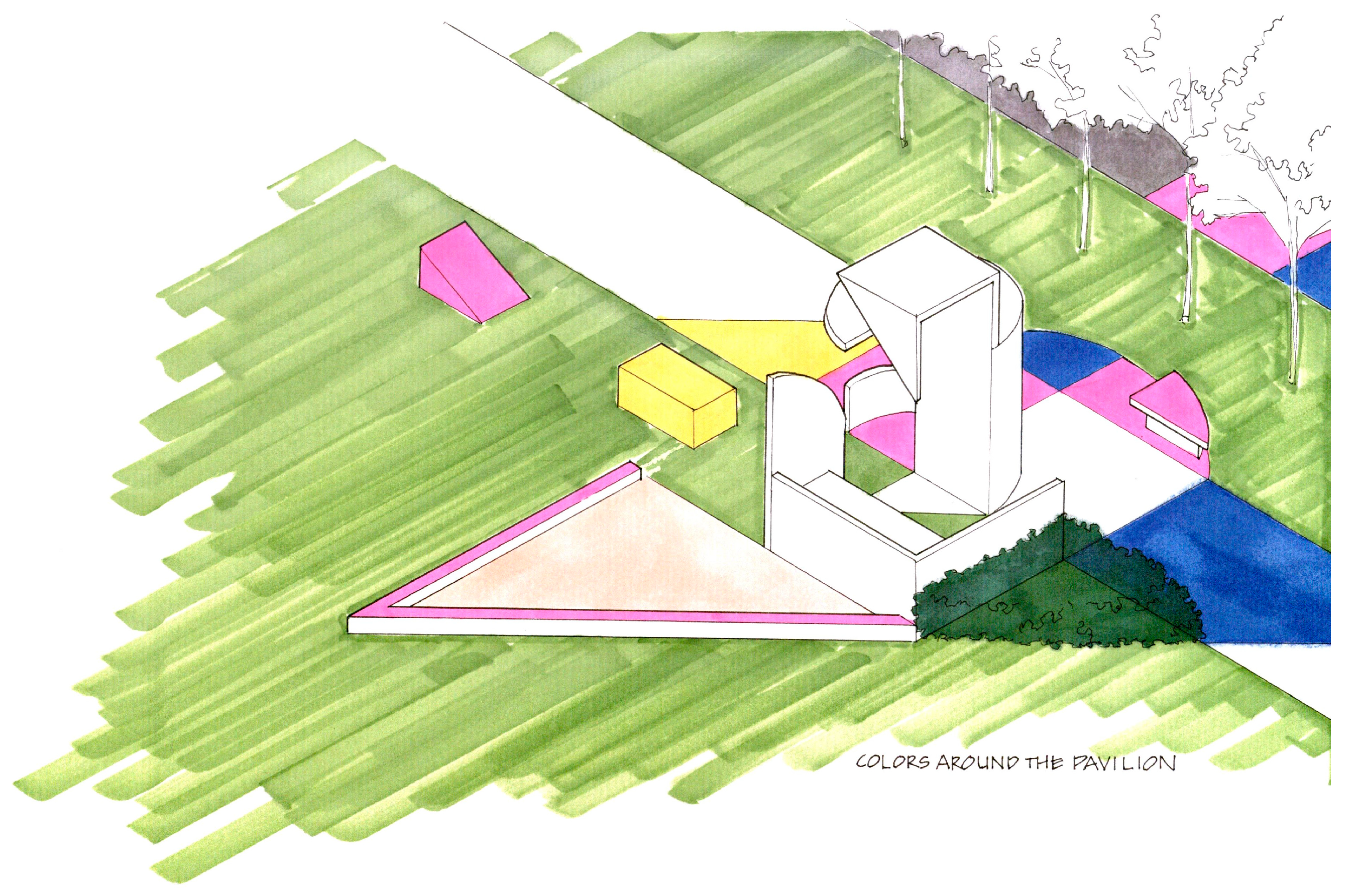

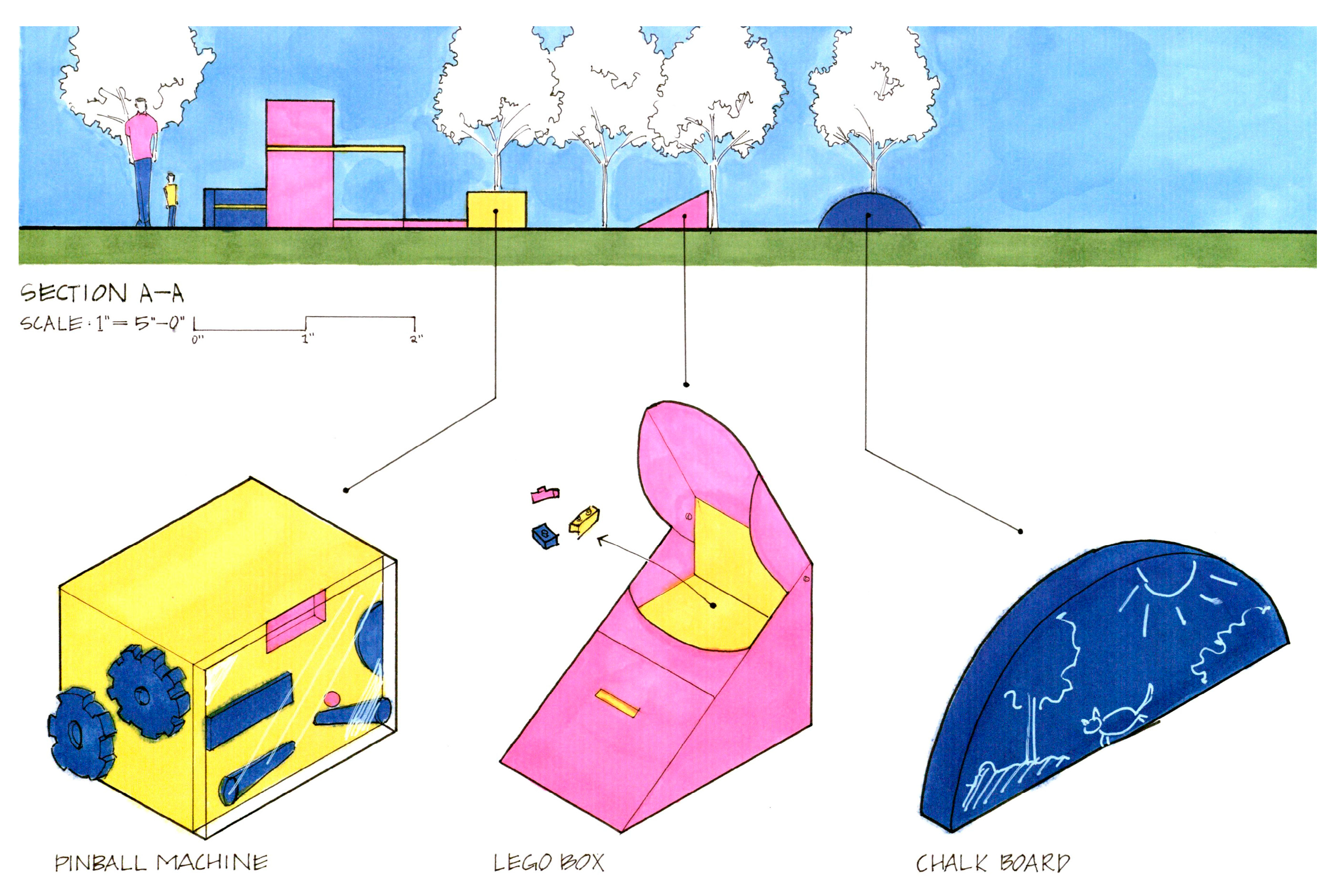

6.6. One Student’s Work Example

The design, Primary Block, provides a safe, fun place for children to stop by on their way after school or to meet up and play with their friends. Thus, the idea of primary shapes and colors, along with kid-friendly, block-like forms, becomes the foundation of the pavilion that joins the neighborhood and the school together.

7. Implications and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AAC&U. (n.d.). Essential learning outcomes. Available online: https://www.aacu.org/trending-topics/essential-learning-outcomes (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Bashier, F. (2014). Reflections on architectural design education: The return of rationalism in The Studio. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 3(4), 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, B. L., Armstrong-Smith, C., Forbes, A., & Holmes, A. C. (2020). Understanding the leadership learner: Priority 3 of the national leadership education research agenda 2020–2025. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14(3), 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, E. L., & Mitgang, L. D. (1996). Building community: A new future for architecture education and practice: A special report. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunoo, V., & Osteen, L. (2016). Purpose, mission, and context: The call for educating future leaders. New Directions for Higher Education, 2016, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranton, P. (2016). Understanding and promoting transformative learning: A guide for educators of adults. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Din, N., Haron, S., & Rashid, R. M. (2016). Can self-directed learning environment improve quality of life? Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 222, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwerike, O. (2022). It takes a village: Leading social change in Africa. Masobe Books. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, R., & Timulak, L. (2021). Descriptive-interpretive qualitative research: A generic approach. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Field, R., Duffy, J., & Huggins, A. (2015). Teaching independent learning skills in the first year: A positive psychology strategy for promoting law student well-being. Journal of Learning Design, 8(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, D. M. E., Doppenberg, J. J., & Oostdam, R. J. (2018). Are more able students in higher education less easy to satisfy? Higher Education, 75(5), 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, K. L., & Priest, K. L. (Eds.). (2022). Navigating complexities in leadership: Moving toward critical hope. Information Age Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz, R. A. (1994). Leadership without easy answers. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz, R. A., Linsky, M., & Grashow, A. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Higher Education Research Institute. (1996). A social change model of leadership development (version III). Higher Education Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- International Society for Technology in Education [ISTE]. (2007). The ISTE national educational technology standards and performance indicators for students. International Society for Technology in Education. Available online: https://iste.org/standards/students (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Kendall, M. R., & Rottmann, C. (2022). Student leadership development in engineering. New Directions for Student Leadership, 173, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, L. E., Priest, K. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2017). Case-in-point pedagogy: Building capacity for experiential learning and democracy. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 7, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Association Press. Available online: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000044218 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Komives, S., Longerbeam, S., Mainella, F., Osteen, L., Owen, J., & Wagner, W. (2009). Leadership identity development. Journal of Leadership Education, 8(1), 11–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komives, S., & Wagner, W. (2016). Leadership for a better world: Understanding the social change model of leadership development (2nd ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Mettetal, G. (2001). The what, why and how of classroom action research. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 2(1), 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B., Haywood, N., Sachdev, D., & Faraday, S. (2008). Independent learning—Literature review (Research Report DCSF-RR051). Department for Children Schools and Families. Available online: https://www.associationforpsychologyteachers.com/uploads/4/5/6/6/4566919/independence_learning_lit_review.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. Jossey-Bass Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks, A., Allen, S. J., McNutt, M. S., & Morrison, J. L. (2018). Discovering leadership: Designing your success. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P., Fahnoe, C., & Henriksen, D. (2013). Creativity, self-directed learning and the architecture of technology rich environments. TechTrends, 57, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, E., & Cebula, A. (2015). Your leadership edge. Kansas Leadership Center. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, E., & Fabris McBride, J. (2023). When everyone leads the toughest challenges get seen and solved. Bard Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, N. (2014). Vertical leadership development—Part 1: Developing leaders for a complex world. Center for Creative Leadership (CCL). [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, N. (2015). The how-to of vertical leadership development—Part 2, 30 experts, 3 conditions, and 15 approaches. Center for Creative Leadership (CCL). [Google Scholar]

- Satterwhite, R., Sarid, A., Cunningham, C. M., Goryunova, E., Crandall, H. M., Morrison, J. L., & McIntyre Miller, W. (2020). Contextualizing our leadership education approach to complex problem solving: Shifting paradigms and evolving knowledge: Priority 5 of the National Leadership Education Research Agenda 2020–2025. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14(3), 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, R. A. (2006). Practical action research for change. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. (2011). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. Routledge Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2016). Generation Z goes to college. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A., & Firth, J. (2011). Qualitative data analysis: The framework approach. Nurse Researcher, 18(2), 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowick, M., & Komives, S. R. (2020). How academic disciplines approach leadership development. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2020(165), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tassone, V., O’Mahony, C., McKenna, E., Eppink, H., & Wals, A. (2018). (Re-)designing higher education curricula in times of systemic dysfunction: A responsible research and innovation perspective. Higher Education, 76(2), 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, T., Chee, T. S., Beng, L. C., Sing, C. C., Ling, K. J. H., Li, C. W., & Mun, C. H. (2010). The self-directed learning with technology scale (SDLTS) for young students: An initial development and validation. Computers & Education, 55(4), 1764–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerri, M., Radford, K., & Shacklock, K. (2018). Student engagement in academic activities: A social support perspective. Higher Education, 75(4), 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Problems, Challenges, and Goals | What I Decided to Achieve | What I Did to Accomplish This |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Problems | Line weight Clarity of diagrams Consistency of sheet composition Hand lettering Margins Clean cut—align edges on models Daily sketching | Applied line weight to axons and diagrams Kept diagrams simple and conveyed more information through graphics than words Drafted hand lettering Did daily sketches as a break |

| Adaptive Challenges | Make the product up to par with process Staying focused in studio (after class, too) Push forward more of own ideas Help others and interact | Put out ideas as if they were the final Did not play music, documented the times I got distracted to remind me to keep working Put out more work than conveyed the design, not just the minimum |

| Personal Goals | Wake up at 8:00 a.m. Stay positive Have more evenings to self | Set up more alarms to wake up early Reminded myself of the joys I found in architecture when I was down |

| Study Objective | Metrics/Evidence | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Develop a stronger identity as a designer. |

|

|

| 2. Enhance time management and planning skills. |

|

|

| 3. Improve the clarity and craftsmanship of design drawings. |

|

|

| 4. Foster self-directed learning and leadership mindsets. |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eshrati, D.; Priest, K.L. Developing Beginning Design Students’ Self-Directed Learning Through Leadership Activity. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040426

Eshrati D, Priest KL. Developing Beginning Design Students’ Self-Directed Learning Through Leadership Activity. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):426. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040426

Chicago/Turabian StyleEshrati, Dorna, and Kerry L. Priest. 2025. "Developing Beginning Design Students’ Self-Directed Learning Through Leadership Activity" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040426

APA StyleEshrati, D., & Priest, K. L. (2025). Developing Beginning Design Students’ Self-Directed Learning Through Leadership Activity. Education Sciences, 15(4), 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040426