‘We’ve Kind of Become More Professional’: Swedish Teaching Teams Enhance Skills with Participation Model for Inclusive Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Perspectives on Inclusive Education

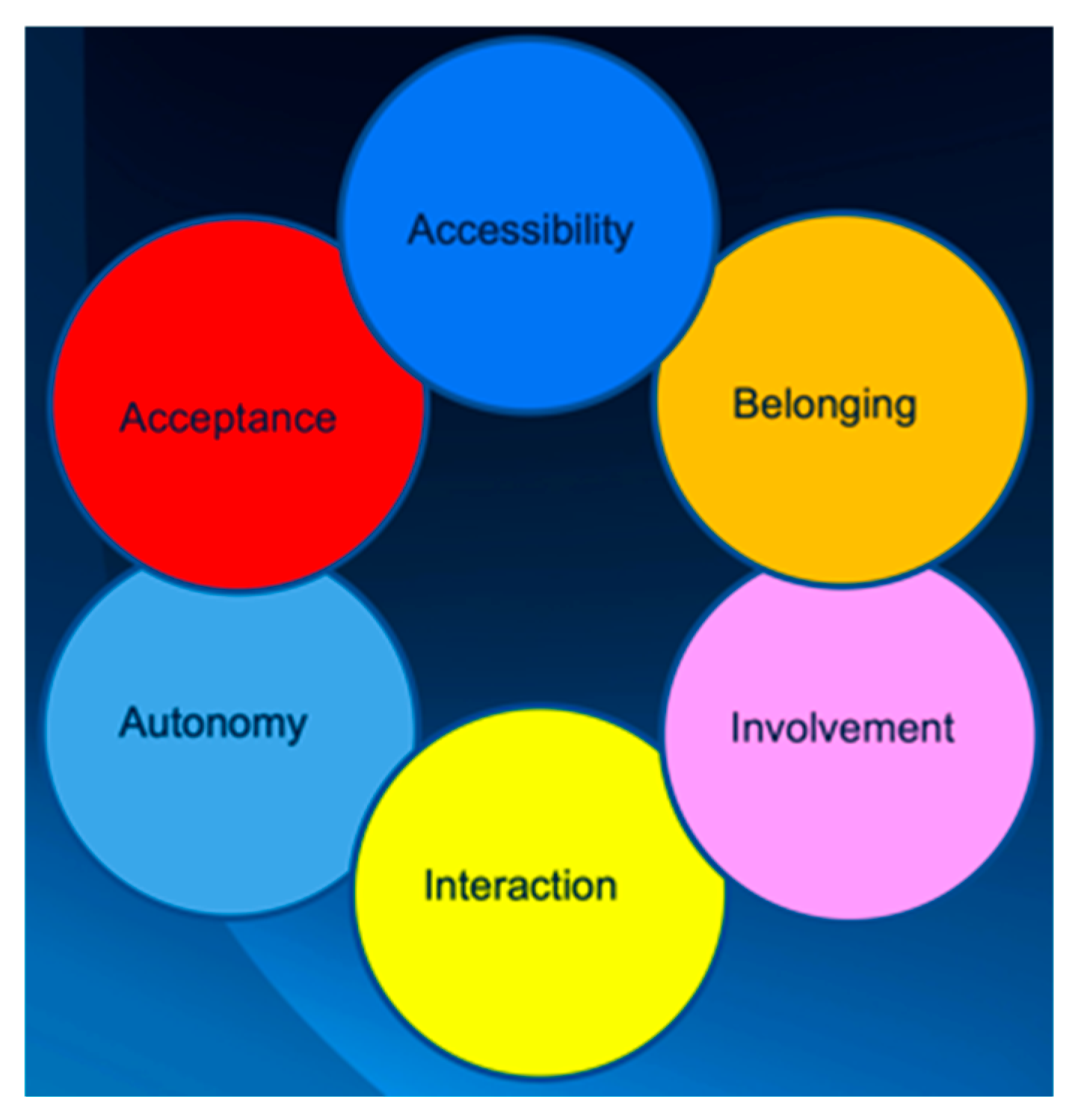

2.2. The Participation Model

2.3. Professionalism to Improve Inclusive Practices

2.4. Professional Development Through Collaboration

3. Theoretical Framework

4. Methods

4.1. Teaching Teams

4.1.1. Team Alpha

4.1.2. Team Omega

4.2. The Intervention

5. Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Organizational Professionalism

This demonstrates that she was not going deeply into TPM but trying to connect the new knowledge to her earlier experiences of cooperative learning, a popular method in (Swedish) schools today, as she recognized its similarities to TPM. This implies that her motivation was stronger in her work with the cooperative learning model, which she had already worked with and was familiar with, while TPM was just something she was instructed to use. Team Alpha expressed that they did not gain profound knowledge during this project, as seen in this quote: ‘Well, we had been under that iceberg. So now it’s like we’ve just been up on top and sniffed around a bit’ (PE, Team Alpha, FGD).Actually, I used most of this cooperative learning, which I see sort of fits in with TPM. Eh, since maybe I’m not looking at the actual model, which part is this? But I still think that, oh, just these parts, they also fit into TPM. So, it’s more that I kind of use the parts found in the cooperative, which is then also in TPM, than I might think about which parts are missing and what I need to add.(CT, Team Alpha, FGD)

6.2. Occupational Professionalism

Yes, but maybe quite a lot of belonging. Because we have … not been involved in almost anything like that, so there has been a lot of focus on that. But also accessibility in different school subjects, to be able to be involved and do the same kind of tasks, although perhaps in a slightly different way, so it doesn’t become completely our own and it is also very social. So it’s probably both the interaction, but mostly belonging, socially. But there is probably also a little interaction with each other and so on.(TA, Team Omega, FGD)

They did not just speak about involvement but specified the part of challenge within the criterion, which is a sign of their professionalization. They also described the outcome of the project as the new professional language they accessed and used in their everyday work at school. They all gave examples of this: ‘But then it was like it became a part of how we communicate around them’ (TA, Team Omega, FGD). They expressed that the concept was not new to them but that they now had a language for it.FT: That is probably what the challenge is, I think. Involvement, challenge, that is also a difficulty that could be improved. We are good at finding solutions for the ones who are on a low level. But that is our next step; it could be to find the right challenges for those in need, for the high achievers.TA: Exactly.(Team Omega, FGD)

It was evident that they agreed on the importance of TPM in supporting the development of a common professional language. The members of Team Omega were aware of their professionalization during this process and demonstrated the importance of occupational professionalism in developing professionalization. They elaborated on what they meant by developing their professional language: ‘It is like a technical term to us. We learned words for what we already knew’ (TB, Team Omega, FGD). This can be interpreted as tacit knowledge developing into professional language. Team Omega discussed the possibility of sharing this language with their colleagues in the rest of the school: ‘We could have the same language and the same concepts, for example, at school’ (FT, Team Omega, FGD).FT: I think this model is so good because it has given us concepts about things that we already…TA and TB: Mm [murmurs of agreement]FT: … do and know and think about. But we haven’t thought of them in these terms. So we’ve kind of become more professional.(Team Omega, FGD)

Time emerged as an important factor in professional development and the opportunity to put theory into practice. Team Omega talked a lot about the value of time: time to meet, time to reflect, time that they were willing to spend, and lack of time. Team Omega had the opportunity to organize their time when they were all in school, since they were three teachers in two classes. Since they decided for themselves to develop participation and inclusive education, they found ways to organize their meeting time. This autonomy of the team seemed to be key to creating a deeper understanding of participation and inclusive education. They seemed to be in charge of their situation and could plan for the next school year. Even though the prerequisites were to be changed, which probably meant less time, they could still find opportunities to continue the work they had started. Unlike Team Alpha, whose motivation was influenced by organizational professionalism and changed based on directions from the principal, Team Omega took charge of their situation. This could be explained by acknowledging the importance of autonomy in gaining occupational professionalism. For example, Team Omega’s teachers discussed possibilities for future work and how they could continue to cooperate even if they were split into different teams.FT: I think that our initial way should be to just tell them briefly about the model, then show how we worked with it. But not to do more than that, and then if they are interested, that’s awesome.TB: Mm.FT: And then they can do it either in their own way…TA: Exactly.FT: … or choose to take our finished model.(Team Omega, FGD)

Another sign of occupational professionalism being connected to the teaching teams’ autonomy was their motivation to develop their work in participation and inclusive education. They used available tools, such as the school platform and a shared digital notebook, to incorporate TPM into their daily work by using TPM criteria to plan future work and lessons for their students.TA: We may be four [teachers] next year. Years four and five, for example.FT: Mm.TB: That could work out really well, actually. Then, we could help each other as well, in some parts.(Team Omega, FGD)

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TPM | The Participation Model |

| FGD | Focus Group Discussion |

| Members of Team Alpha | |

| CT | Class Teacher |

| PE | Teacher in Physical Education |

| RP | Resource Pedagogue |

| SP | Special Educational Needs Coordinator |

| Members of Team Omega | |

| FT | First and Class Teacher |

| TA | Class Teacher A |

| TB | Class Teacher B |

References

- Algraigray, H. (2023). Professionalism and the challenges of inclusion: An evaluation of special education teachers’ practice. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences, 10(7), 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, P. E. (2009). Professional development and teacher aides in inclusive education contexts: Where to from here? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(8), 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, A., & Gorman, A. (2023). Leading transformative professional learning for inclusion across the teacher education continuum: Lessons from online and on-site learning communities. Professional Development in Education, 49(6), 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buli-Holmberg, B., Høybråten Sigstad, H. B., Morken, I., & Hjörne, E. (2023). from the idea of inclusion into practice in the nordic countries: A qualitative literature review. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 38(1), 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, A., & Millward, A. (2000). Schools and special needs: Issues of innovation and inclusion. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Edström, K. (2023). Student Participation in Reading Classes in a Swedish Compulsory School for Students Diagnosed with Intellectual Disability. Education Sciences, 13(9), 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edström, K., Gardelli, V., & Backman, Y. (2022). Inclusion as participation: Mapping the participation model with four different levels of inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 28(12), 2940–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evetts, J. (1999). Professionalisation and professionalism: Issues for interprofessional care. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 13(2), 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evetts, J. (2013). Professionalism: Value and ideology. Current Sociology, 61(5–6), 778–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, K., Lindqvist, G., Klang, N., Magnússon, G., & Almqvist, L. (2018). Professionalism, governance and inclusive education—A total population study of swedish special needs educators. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(6), 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradén, M., & Irisdotter Aldenmyr, S. (2023). Praktikutvecklande samtal på vetenskaplig grund. Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige, 28(3), 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnþórsdóttir, H., Sverrisdóttir, A. B., Þrastardóttir, B., Óskarsdóttir, E., & Ragnarsdóttir, H. (2024). The role of school leaders in developing inclusive practices in icelandic compulsory schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 39(6), 928–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, S., ten Braak, D., & Munthe, E. (2022). Inclusion of students with special education needs in nordic countries: A systematic scoping review. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 68(3), 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Florian, L., & Pantic, N. (2022). The development of inclusive practice under a policy of integration. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(10), 1068–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, W. (2020). Organising inclusive schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(12), 1340–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., & Ruppar, A. (2021). Conceptualizing teacher agency for inclusive education: A systematic and international review. Teacher Education and Special Education, 44(1), 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreman, T. (2014). Measuring inclusive education outcomes in Alberta, Canada. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(5), 459–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, E. (2013). Social delaktighet i teori och praktik om barns sociala delaktighet i förskolans verksamhet [Ph.D. thesis, Stockholm University]. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:606868/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Miller, A. L., Wilt, C. L., Allcock, H. C., Kurth, J. A., Morningstar, M. E., & Ruppar, A. L. (2020). Teacher agency for inclusive education: An international scoping review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(12), 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minow, M. (1985). Learning to live with the dilemma of difference: Bilingual and special education. Law and Contemporary Problems, 48(2), 157–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilholm, C. (2006). Special education, inclusion and democracy. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 21(4), 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilholm, C. (2021). Research about inclusive education in 2020—How can we improve our theories in order to change practice? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(3), 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östlund, D. (2012). Deltagandets kontextuella villkor fem träningsskoleklassers pedagogiska praktik [Ph.D. thesis, Malmö University]. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, E. (2013). Raising achievement through inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(11), 1205–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlin, S. (2023). Teachers making sense of principals’ leadership in collaboration within and beyond school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 67(5), 754–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, S. (2024). Epilogue: Towards a more comprehensive understanding of inclusive and special education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 39(6), 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szönyi, K. (2020). Delaktighet i lärmiljön: Delaktighet—Ett stöd för en inkluderande lärmiljö. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- Szönyi, K., & Söderqvist Dunkers, T. (2018). Delaktighet: Ett arbetssätt i skolan (Rev. ed.). The National Agency for Special Needs Education and Schools, SPSM. [Google Scholar]

- The Swedish Schools Inspectorate. (2018). Att skapa förutsättningar för delaktighet i undervisningen (400-2016-11440). The Swedish Schools Inspectorate. Available online: https://www.skolinspektionen.se/beslut-rapporter-statistik/publikationer/kvalitetsgranskning/2018/att-skapa-forutsattningar-for-delaktighet-i-undervisningen/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- UNESCO. (1994). Final report: World conference on special needs education: Access and quality. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., & Struyf, E. (2023). Professional development initiatives as a lever for inclusive education: A multiple case study using qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). Professional Development in Education, 49(3), 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard U.P. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Edström, K.; Cervantes, S. ‘We’ve Kind of Become More Professional’: Swedish Teaching Teams Enhance Skills with Participation Model for Inclusive Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020226

Edström K, Cervantes S. ‘We’ve Kind of Become More Professional’: Swedish Teaching Teams Enhance Skills with Participation Model for Inclusive Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(2):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020226

Chicago/Turabian StyleEdström, Kattis, and Sara Cervantes. 2025. "‘We’ve Kind of Become More Professional’: Swedish Teaching Teams Enhance Skills with Participation Model for Inclusive Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 2: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020226

APA StyleEdström, K., & Cervantes, S. (2025). ‘We’ve Kind of Become More Professional’: Swedish Teaching Teams Enhance Skills with Participation Model for Inclusive Education. Education Sciences, 15(2), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020226