Reading Interventions to Support English Learners with Disabilities in High School: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. ELs with Disabilities

1.2. Academic Achievement

1.3. High School

1.4. Purpose

- What are the characteristics of ELs with disabilities in high school across the reading intervention studies?

- What are the characteristics of the reading interventions for ELs with disabilities in high school?

- What are the reading outcomes for ELs with disabilities in high school?

2. Method

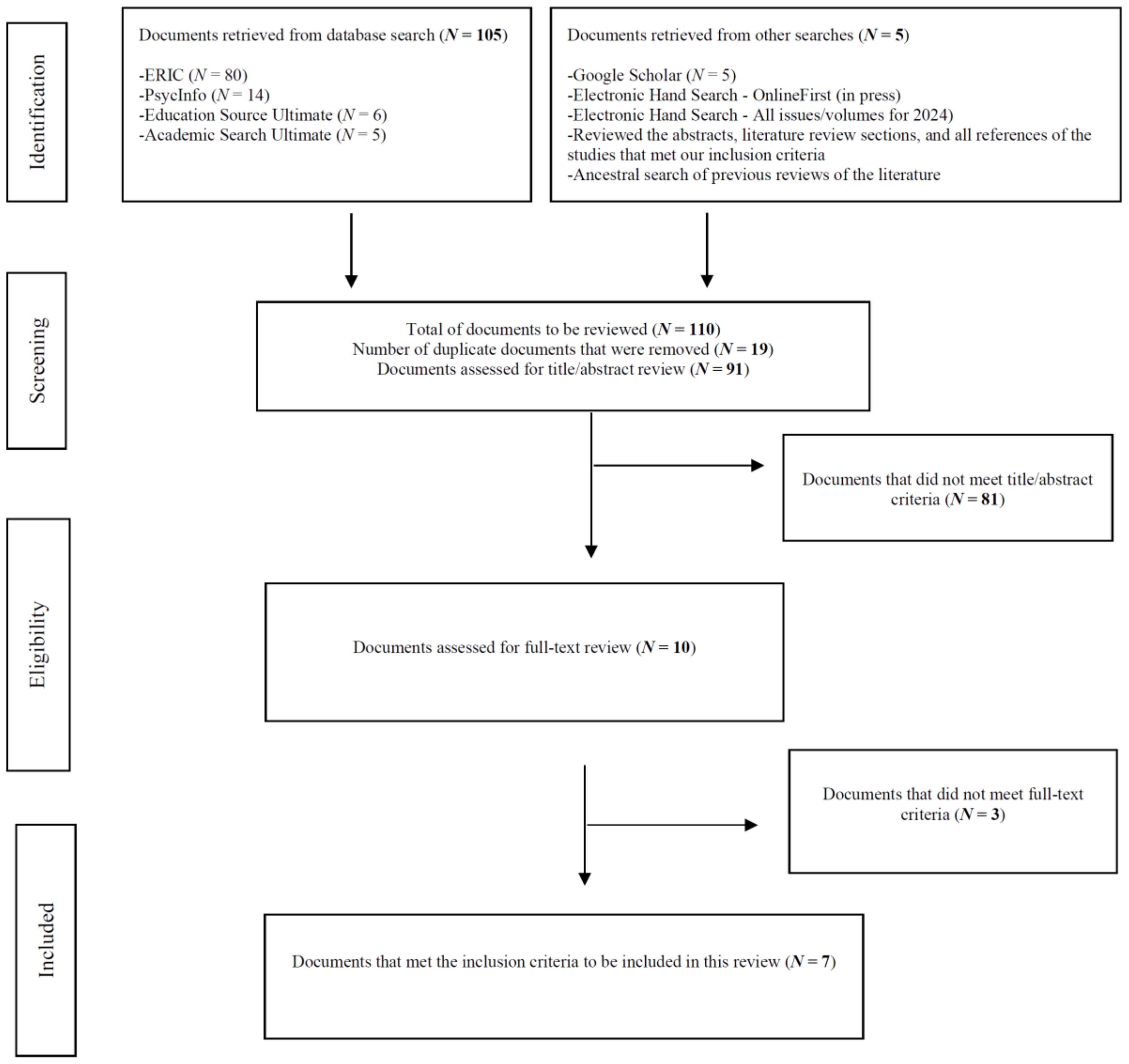

2.1. Literature Search and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Interrater Reliability

2.5. Coding

2.6. Participant Characteristics

2.7. Study and Intervention Characteristics

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of ELs with Disabilities in High School

3.2. Disability

3.3. Age/Grade Level

3.4. Gender

3.5. Ethnicity

3.6. Native Language and Native Language Proficiency

3.7. English Language Proficiency

3.8. Reading Levels

3.9. Characteristics of Reading Interventions for ELs with Disabilities in High School

3.10. Target Skills, Types of Reading Interventions, and Outcomes

3.11. Intervention Agents

3.12. Research Designs

3.13. Dependent Measures

3.14. Setting and Format

3.15. Duration and Intensity

3.16. Treatment Fidelity

3.17. Social Validity

3.18. Inter-Observer Agreement

3.19. Data Collection Methods

3.20. Reading Outcomes for ELs with Disabilities in High School

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Implications for Research

4.4. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Boon, R. T., & Barbetta, P. M. (2017). Reading interventions for elementary English language learners with learning disabilities: A review. Insights into Learning Disabilities, 14(1), 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, R. T., Burke, M., & Bowman-Perrott, L. (2020). Literacy instruction for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: Research-based interventions for classroom practice. Information Age Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, R. T., & Spencer, V. (2023). English learners with learning disabilities: A collaborative practice guide for educators. Information Age Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, L., Herrera, S. G., & Murry, K. (2010). Reading difficulties and grade retention: What’s the connection for English language learners? Reading and Writing Quarterly, 26(1), 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C., Steinle, P. K., & Vaughn, S. (2019). Reading instruction for English learners with learning disabilities: What do we already know, and what do we still need to learn? In D. J. Francis (Ed.), Identification, classification, and treatment of reading and language disabilities in Spanish-speaking EL students (pp. 145–189). New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, no. 166. Wiley Periodicals, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hallahan, D. P., Kauffman, J. M., & Pullen, P. C. (2023). Exceptional learners: An introduction to special education (15th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Halterman, T. (2013). Effects of RAP paraphrasing and semantic-mapping strategies on the reading comprehension of English learners and fully-English-proficient students with mild-to-moderate learning disabilities [Ph.D. dissertation, The University of San Francisco]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. Available online: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/79/ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Helman, A. L., Calhoon, M. B., & Kern, L. (2015). Improving science vocabulary of high school English language learners with reading disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 38(1), 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helman, A. L., Dennis, M. S., & Kern, L. (2022). Clues: Using generative strategies to improve the science vocabulary of secondary English learners with reading disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 45(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S. L., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practices in special education. Exceptional Children, 71, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, E. A., Brigham, F. J., D’Agostino, S., & Finn, J. E. (2023). A reading intervention with ELs with disabilities at the high school level. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 39(5), 436–454. [Google Scholar]

- House, A. E., House, B. J., & Campbell, M. B. (1981). Measures of interobserver agreement: Calculation formulas and distribution effects. Journal of Behavioral Assessment, 3(1), 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddle, S., Hosp, J., & Watt, S. (2017). Reading interventions for adolescent English language learners with reading difficulties: A synthesis of the evidence. Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners, 17(2), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). (2004). Pub. L. No 94–142, 20 U.S.C. §1415. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/20/1415 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Institute of Education Sciences. (2017). Standards Handbook, Version 4.0. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/WWC/Docs/referenceresources/wwc_standards_handbook_v4.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Jozwik, S. L., Freeman-Green, S., Kaczorowski, T. L., & Douglas, K. H. (2021). Effects of peer-assisted multimedia vocabulary instruction for high school English language learners. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 37(1), 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas, S. E. N., Dai, S., & Ardasheva, Y. (2023). The intersection of language and disability: Progress of English learners with disabilities on NAEP reading. The Journal of Special Education, 58(2), 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisoli, K. L. (2010). Effects of repeated reading on reading fluency of diverse secondary level learners [Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Arizona]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. Available online: https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/145364 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Parker, R., & Vannest, K. (2009). An improved effect size for single-case research: Nonoverlap of all pairs. Behavior Therapy, 40, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Sauber, S. B. (2011). Combining non-overlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 35, 202–322. [Google Scholar]

- Rhinehart, L. V., Bailey, A. L., & Haager, D. (2024). Long-term English learners: Untangling language acquisition and learning disabilities. Contemporary School Psychology, 28(1), 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards-Tutor, C., Baker, D. L., Gersten, R., Baker, S. K., & Smith, J. M. (2016). The effectiveness of reading interventions for English learners: A research synthesis. Exceptional Children, 82(2), 144–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (1998). Summarizing single-subject research: Issues and applications. Behavior Modification, 22(3), 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solari, E. J., Kehoe, K. F., Cho, E., Hall, C., Vargas, I., Dahl-Leonard, K., Richmond, C. L., Henry, A. R., Cook, L., Hayes, L., & Conner, C. (2022). Effectiveness of interventions for English learners with word reading difficulties: A research synthesis. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 37(3), 158–174. [Google Scholar]

- Texas Education Agency. (2023–2024). Public education information management system data on emergent bilingual students in Texas (fact sheet #1–statistics). Available online: https://www.txel.org/media/hxcfzvqe/factsheet1-statistics.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- U.S. Department of Education. (2017). English learner tool kit, 2nd rev. ed.; Office of English Language Acquisition, U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://ncela.ed.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/files/english_learner_toolkit/OELA_2017_ELsToolkit_508C.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- U.S. Department of Education. (2021). English learners with or at risk for disabilities. Inside IES Research: Notes from NCER & NCSER. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Special Education Research. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/blogs/research/post/english-learners-with-or-at-risk-for-disabilities (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- U.S. Department of Education. (2022). NAEP report card: Reading. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences. 1992–2022. Available online: https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading/nation/achievement/?grade=12 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- U.S. Department of Education. (2024). The condition of education 2024. National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences. 1992–2022. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2024144 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Williams, K. J., & Vaughn, S. (2020). Effects of an intensive reading intervention for ninth-grade English learners with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 43(3), 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Disability | Age (yrs/mo) | Grade | Gender | Ethnicity | Native Language | Native Language Proficiency | English Language Proficiency Assessment and Score | Reading Assessment and Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halterman (2013) | LD (n = 11) | NR | 9 | NR | NR | Spanish | NR | IPT-II Early Intermediate (n = 8) Intermediate (n = 1) Early Advanced (n = 2) | Gates–MacGinitie 4–8 yrs below grade level (1st through 5th grade) |

| Helman et al. (2015) | LD (n = 3) | 14 yrs 3 mo to 16 yrs 2 mo | 9 and 10 | M (n = 2) F (n = 1) | Hispanic (n = 3) | Spanish | NR | Pre-LAS (English) Beginning (n = 4) | Read 180 SRI Lexile 808 Lexile (n = 1; 6th grade) 640 Lexile (n = 1; 4th grade) 785 Lexile (n = 1; mid-5th grade) |

| Helman et al. (2022) | LD (n = 4) | 16 yrs 1 mo to 16 yrs 9 mo | 10 | M (n = 1) F (n = 3) | Hispanic (n = 4) | Spanish | NR | WIDA Beginning (n = 4) | Read 180 SRI Lexile 632 (n =1; 4th grade) 615 (n =1; 4th grade) 601 (n =1; 4th grade) 600 (n =1; 4th grade) |

| Horton et al. (2023) | LD and SL (n = 2) SL (n = 1) | 15 yrs 1 mo to 17 yrs 5 mo | 9 and 11 | M (n = 2) F (n = 1) | Hispanic (n = 2) Afghani (n = 1) | Spanish (n = 2) Persian (n = 1) | NR | NR Level 3 (n = 2) Level 4 (n = 1) | NR |

| Jozwik et al. (2021) | LD (n = 1) | NR | 9 | NR | Guatemalan (n = 1) | Spanish | NR | ACCESS Emerging 2.0 (n = 1) | NR |

| Morisoli (2010) | LD (n = 3) | 15 yrs to 17 yrs | 9–11 | M (n = 3) | Hispanic (n = 3) | Spanish | NR | AZELLA Intermediate (n = 1) Proficient (n = 2) | TOWRE 1 WJ-III ACH 1 GORT-4 1 3rd grade (n = 1) 4th grade (n = 2) |

| Williams and Vaughn (2020) | LD (n = 71) | NR | 9 | U | U | NR | NR | NR U | NR |

| Study | Number of ELs | Intervention and Intervention Agents | Research Design | Reading Skills | Dependent Measures | Setting and Format | Treatment Duration, Intensity, and Sessions | Treatment Fidelity Method (Percentage) | Social Validity Instrument | IOA 1 (Percentage) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halterman (2013) | n = 11 | C1: Traditional, RAP Paraphrasing Strategy, and Semantic Map Strategy C2: Traditional, Strategy Semantic Map Strategy, and RAP Paraphrasing Teacher | SCR–repeated measures with ATD | C | Reading comprehension Number of RAP steps recalled Number of semantic map steps recalled | SPED English classroom Whole group | 10 weeks T1 = 9 lessons 540 minutes total T2 = 9 lessons 540 minutes total | DO (NR) | NR | NR |

| Helman et al. (2015) | n = 3 | Clue Word Strategy Researcher (Doctoral Student) | SCR–MBD ABAB reversal across participants | V | Strategy use Strategy knowledge Oral strategy steps | Pull-out 1:1 | 2 weeks 45 minutes 3 days/week to mastery | Checklists, DO (100%) | CIRP | PP (100%) |

| Helman et al. (2022) | n = 4 | CLUES Strategy SPED Teacher | SCR–MBD across participants | V | Strategy use Strategy knowledge Near transfer Far transfer | In-class (ESOL) | 3 weeks 4 days a week | Checklists (>95%) | CIRP | AT (30%, 90–100%) |

| Horton et al. (2023) | n = 3 | Modified GIST Strategy Researcher (Doctoral Student) | SCR–MPD across participants | C | Expository paragraph summary score | Pull-out 1:1 | Tutoring phase: 2 weeks 20–50 minutes each 6 sessions Intervention phase: NR 12–47 minutes each 5 sessions | Checklist (98.76%) | AMRP | Summary statement scores (100%) GIST strategy rubric (95.02%) |

| Jozwik et al. (2021) | n = 1 | Peer-Assisted Multimedia Vocabulary Instruction ESL Teacher | SCR–MPD across word sets replicated across participants | V | Number of words defined correctly | In-class Dyads | 5 days/week 45 minutes/day | DO Self- regulation training (93%) Intervention (98.5%) | Researcher- created questionnaire | PP Accuracy on expressive definition tests (93%) |

| Morisoli (2010) | n = 3 | GL Repeated Readings with Systematic Error Correction and Performance Feedback (Story Passages Only) SPED Teacher/ Researcher | SCR–ABAB reversal across participants | F | Words per minute Errors per minute | Pull-out 1:1 | 12 weeks 15–20 minutes 3–4 days/week | NR (99.87%) | NR | (>90%) |

| Williams & Vaughn (2020) | n = 85 | RIA Reading Interventionists | Group with participants randomly assigned to a treatment or a comparison group | F, C, and V | Phonemic Decoding Sight words Vocabulary Reading comprehension | Reading intervention class Groups of 10–15 | 2 semesters (1 year) 3.74–4.25 hours/week NR | Checklist (2.5–3.3 on a 4.0-point scale) | NR | NR |

| Study | Outcome | Effect Size | Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halterman (2013) | Gains in reading comprehension Gains in semantic mapping Gains in written factual recall Gains in multiple-choice factual recall Gains in multiple-choice far transfer | Semantic mapping d = 1.95 RAP paraphrasing strategy d = 1.13 | Text recall was “relatively stable” (p. 45) Gains maintained in factual recall and far transfer for all but one student after 2 weeks |

| Helman et al. (2015) | Improved proficiency in analyzing science vocabulary with the Clue Word Strategy | ---- | Gains in analyzing science vocabulary were maintained after 2 months |

| Helman et al. (2022) | Students needed graphic organizers to remind them of CLUES steps Students were able to produce most of the root words learned, but produced very few prefixes and suffixes | ---- | Gains in strategy use (correctly writing morphemes, morpheme meanings, and science term meanings) after 2 weeks and 4 weeks Better on near- than far-transfer generalization, but they were able to arrive at the meaning of new science vocabulary with context clues and by analyzing morphemes |

| Horton et al. (2023) | Improvements in reading comprehension | Text summarization (Alphonzo) NAP = 1.00, p < 0.01 Tau-U = 1.00, p < 0.01 Text summarization (Bryan) NAP = 1.00, p < 0.01 Tau-U = 1.00, p < 0.01 Text summarization (Corrine) NAP = 1.00, p < 0.01 Tau-U = 1.00, p < 0.01 | Gains maintained after 2 weeks |

| Jozwik et al. (2021) | Improved number of accurate expressive definitions Increase in self-reporting of higher levels of word knowledge | PND = 91% | Students maintained subject-specific vocabulary definitions on two subject-specific word sets after 11 to 3 weeks, respectively |

| Morisoli (2010) | More words read correctly Fewer mistakes made reading passages | ---- | |

| Williams and Vaughn (2020) | No significant improvements in reading fluency Non-statistically significant effects for reading comprehension (overall) Improvements in sentence-level comprehension | Proximal vocabulary measure g = 0.41 2 Word reading g = 0.08–0.18 3 Sentence-level comprehension g = 0.14 4 | ---- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bowman-Perrott, L.; Boon, R.T.; Ewoldt, K.B.; Burke, M.D.; Eslami, Z.; Mirzaei, A. Reading Interventions to Support English Learners with Disabilities in High School: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020223

Bowman-Perrott L, Boon RT, Ewoldt KB, Burke MD, Eslami Z, Mirzaei A. Reading Interventions to Support English Learners with Disabilities in High School: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(2):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020223

Chicago/Turabian StyleBowman-Perrott, Lisa, Richard T. Boon, Kathy B. Ewoldt, Mack D. Burke, Zohreh Eslami, and Azizullah Mirzaei. 2025. "Reading Interventions to Support English Learners with Disabilities in High School: A Systematic Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 2: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020223

APA StyleBowman-Perrott, L., Boon, R. T., Ewoldt, K. B., Burke, M. D., Eslami, Z., & Mirzaei, A. (2025). Reading Interventions to Support English Learners with Disabilities in High School: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences, 15(2), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020223