Abstract

The use of augmented reality, assistive technology (AT), and augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) offers a promising opportunity to significantly enhance the general reading abilities of students with specific learning disorders (SLDs) by providing effective learning tools. This study aimed to assess students’ learning experiences to understand the effectiveness of AT and AAC in language skills development and identify the AT tools and devices commonly used in classroom settings, with the goal of better informing practitioners. A systematic literature review was conducted across various databases, resulting in the inclusion of 22 relevant articles, focusing on multiple implications of AT and AAC. Common factors associated with the implementation of AT in teaching students with SLDs were identified, and a thematic analysis revealed recurring patterns regarding the impact of AT solutions on students with SLDs. The findings indicate notable improvements in language skills among students with SLDs, including vocabulary, spelling, orthography, phonological awareness, and reading comprehension. However, two studies reported limited effects or no effects on language skills, self-efficacy, and self-esteem. This review shows that AT and AAC effectively support language skills development and outcomes for students with SLDs. Nevertheless, given the limited number of studies and the complexity of the factors explored, these conclusions should be interpreted with caution.

1. Introduction

Communication is crucial to the learning process and for its independence. Once oral language was established, it became easier to pass knowledge from older generations to younger ones. The discovery of written language further revolutionized this process, making knowledge transmission more efficient and accelerating human progress. The knowledge that one generation acquires is not lost. Therefore, communication and language skills, including the acquisition of reading, writing, and understanding mathematical language, are fundamental to academic learning (Abdelraouf et al., 2018). Language acquisition is a complex process, often taken for granted by teachers and parents. However, some children face significant challenges in acquiring reading and writing skills, which may be due to specific learning disorders (SLDs).

The prevalence of school-age children across different languages and cultures who struggle with learning language is around 5–15% (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), meaning that SLDs are among the most widespread and significant disorders affecting school-age children (Khodeir et al., 2020). Language deficits in students struggling with SLDs are correlated with significant impairments in academic and social skills (Khodeir et al., 2020).

SLDs refer to a range of difficulties that affect the acquisition of key academic skills, such as reading (dyslexia), writing (dysgraphia), and arithmetic (dyscalculia), all of which are essential for learning (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). SLD serves as an umbrella term for a group of neurodevelopmental disorders that share common symptoms. The primary challenge faced by individuals with SLDs is the inability to attain and maintain fluency in language skills, including spoken, written, sign language, and mathematical language, due to deficits in comprehension or production (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Children with SLDs encounter difficulties in fluent and efficient reading, particularly in terms of speed, automaticity, and executive coordination (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These challenges typically arise during the early years of formal education and, without proper support, can significantly hinder learning (Perdue et al., 2022). Symptoms commonly include word decoding and spelling, phonological processing, and orthographic–phonological integration (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Perdue et al., 2022). As a result, the overall profile of reading and writing skills for students with SLDs often falls below the level expected for their intelligence, motivation to learn, socio-cultural environment, and available learning opportunities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

In addition to difficulties with language and academic skills, researchers have identified other challenges that students with SLDs face in school settings. These include challenges in academic learning requiring reading skills (Miciak et al., 2022), attention deficits and short attention span, poor motor skills (Toffalini et al., 2017), difficulties with coordination and spatial reasoning, poor time management, planning, and organisational skills (Hendriksen et al., 2007), and difficulties with processing and organising information (Toffalini et al., 2017). Despite long-term intervention and remediation, these difficulties persist (Cleugh & Kirk, 1963), and teachers report a significant gap between a student’s potential and their actual performance (Rohmer et al., 2022). As academic learning that happens in schools is mostly based on literacy skills, it becomes crucial for students to practice using language in oral and written form, which is effortful for children with SLDs, and their academic success is strongly correlated with personalised, intensive, and continuous educational support (Al-Dababneh & Al-Zboon, 2022; Benney et al., 2022; Dhingra et al., 2024). Therefore, students with SLDs would greatly benefit from individualised learning pathways and rehabilitation strategies to compensate for the challenges that a learning disorder may pose to the learning process. However, research is needed to provide a personalised user experience for the specific needs and challenges of students with SLDs, based on a viable mechanism that can adapt to individual differences and specific learning and verbal behaviours, different interaction modalities, and customised types of multimedia feedback (Al-Thanyyan & Azmi, 2021). The use of AAC and the adoption of new technologies offer potentially viable solutions for improving and enhancing literacy skills and communication for students with SLDs (Wood et al., 2018).

AAC systems refer to any system that supports (augmentative) or replaces (alternative) oral communication, —essentially, any communication method other than natural speech (Beukelman & Light, 2020). The incorporation of AAC in education is intended to improve communication and make it effective. Language helps us to (1) express and understand each other by using words to build sentences, and sentences to build conversations; (2) arrange information in the right order to obtain meaning and significance; and (3) understand and capture the meaning of others’ discourse (Leeds-Hurwitz, 1993). AAC systems have been developed to compensate in instances when natural communication is challenged, and individuals are unable to use verbal language to meet all of their communication needs. AAC can be used either to augment communication or to provide an alternative as a primary means of communication (Andzik & Chung, 2022). The American Speech–Language–Hearing Association (ASHA, 1992) describes AAC as a tool to compensate temporarily or permanently for disabilities, activity limitations, and participation restrictions in verbal production, both oral and written. AAC systems are used by people who are unable to use verbal language for a limited or unlimited period (Andzik & Chung, 2022; Broomfield et al., 2022; Burnham et al., 2023).

AAC refers not only to aided and unaided systems of communication, but also to various strategies and techniques that use symbols and low- and high-tech aids to augment, support, or replace natural language production (Beukelman & Light, 2020; Holyfield et al., 2023). AAC is therefore used to support the communication of individuals with unintelligible speech and to provide an alternative means of communication for those who have no oral language or who have not developed sufficient verbal expressive skills to communicate effectively. AAC users include people with congenital and/or acquired disabilities that affect their ability to communicate verbally, such as individuals with autism, cerebral palsy, dual sensory impairment, intellectual disabilities, multiple disabilities, and strokes. For example, a child with Down syndrome who has not yet developed intelligible speech may use an augmentative communication device or system to improve understanding and expression. As their oral language becomes more intelligible, the use of these devices may only be necessary in new or complex communication situations.

Recent technological developments have led to the development of different AAC solutions to facilitate language development and speech production to meet diverse communication needs. The augmented reality (AR) paradigm (Wang et al., 2022), together with the use of AAC and AT, has significant potential to improve students’ reading skills (Schiavo et al., 2021; Wood et al., 2018) by providing effective learning tools. Importantly, the aim of these tools is not to replace verbal language (oral or written), but to complement and support its development, particularly for students with SLDs. Verbal language development—both oral and written—remains the primary goal of intervention strategies for this population.

In the context of SLDs, AAC serves as a supportive tool to enhance literacy experiences and complement oral language development, rather than as a substitute for verbal communication, as is often the case for individuals with severe communication impairments who rely on AAC as their primary mode of communication. This perspective highlights the potential of AAC tools to enhance literacy experiences while supporting oral language development. However, research investigating the use of AAC in intervention strategies for students with SLDs remains limited. Addressing this gap is critical to guide educators, teachers, and policy makers in making research-based decisions about effective educational interventions.

The three research questions in this systematic literature review (SLR) were designed to explore key aspects of the use of AAC by students with SLDs. These questions were informed by two factors: (1) fundamental gaps identified in the literature regarding the use of AAC in SLD education, and (2) emerging findings from existing studies that highlighted barriers and opportunities related to the implementation of AAC. The aim was to explore areas that are critical to both theoretical understanding and practical application in educational settings:

RQ 1: What types of barriers and limitations are identified by teachers when using AAC and AT when working with students with SLDs? This question arose from the recognition that teachers play a central role in the implementation of AAC tools and that understanding their perspectives on barriers is essential to improving usability and adoption.

RQ 2: What features of AAC and AT should be assessed to ensure their feasibility and usability by students with SLDs? Insights into the design and functionality of AAC tools are essential to ensure that they meet the needs of both students and educators in classroom settings.

RQ3: How can the process of literacy development benefit from AAC or AT? The literature suggests potential for AAC to improve written language skills, but this area requires further research to identify specific strategies and outcomes.

Aim of the study

The purpose of this study was to assess students’ learning experiences in relation to the effectiveness of AAC in developing language skills, particularly written language, and to examine AAC tools and devices used in the classroom. The findings are intended to provide evidence-based recommendations for educators and practitioners to ensure that AAC interventions are both effective and accessible for students with SLDs.

2. Materials and Methods

A literature review was undertaken to summarise the current body of research on the impact of using AAC with students with SLDs and the intervention strategies implemented, and to provide guidance for further research. The rationale of conducting this SLR was to ensure reliable and rigorous knowledge for educators, professionals working with students with SLDs, and parents about where and how to use AAC tools.

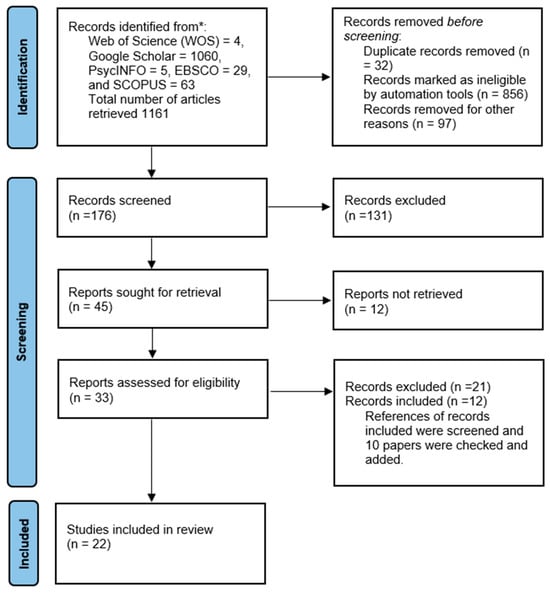

The methodology of this SLR was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA methodology) (Moher et al., 2016). The inclusion, exclusion, and quality criteria are listed below. The articles selected for review were coded according to the coding categories and criteria presented below.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Due to the diversity of studies conducted on AAC use, several inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to identify relevant studies. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) peer-reviewed publications; (b) studies on the use of AAC in classrooms with students with SLDs; (c) timeline of the papers: 1 January 2012–1 August 2022; and (d) target groups: teachers and professionals working with students with SLDs. The decision to include studies published from 2012 onwards was guided by the rapid advances in technology and educational tools over the past decade. AAC technologies, as well as assistive technologies more broadly, have evolved significantly in recent years, particularly in their applications to support language and literacy development. By focusing on studies from 2012 onwards, we aimed to ensure the inclusion of research that reflects contemporary tools and methodologies, as well as the pedagogical practices that are most relevant to current educational contexts. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) articles not related to the use of AAC with students with SLDs; and (b) articles not exploring the use of AAC in school settings.

2.2. Quality Criteria

After the initial search, articles were assessed for quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Pluye et al., 2009), considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The quality criteria were validated by a group of experts from the author’s institution to ensure an efficient selection of articles. A qualitative synthesis was conducted to organise, analyse, and interpret all relevant data through interpretive, comparative, pattern, and relational analyses (Bazeley, 2013). The abstracts of the 176 articles were screened according to the inclusion criteria. Studies that did not meet the established criteria were excluded, resulting in 45 articles being selected (131 excluded studies). The remaining 45 studies were divided into two sections, which were screened by two independent experts according to the quality criteria. After this step, a further 33 studies were excluded. In total, t22 studies were included in the final review.

2.3. Search Methods

To address the above research questions, it was necessary to identify a sample of articles. The following electronic databases were selected for this purpose: Web of Science (WOS), PsycINFO, ScienceDirect, EBSCO, and SCOPUS. The following search string was used: (“augmentative and alternative communication” OR “assistive technology” OR “AAC”) AND (“specific learning disorder” OR “SLD” OR “dyslexia” OR “learning disorders”) AND (“reading disorder” OR “reading difficulty” OR “reading impairment”). The literature search process involved several stages, including identifying relevant studies aligned with our research aims, assessing their quality, identifying patterns and significant findings, and evaluating their relevance to the research questions. A total of 176 articles were identified, out of which 12 were selected based on the criteria. Due to the limited number of studies investigating the use of AAC in relation to SLDs, a further stage was added which involved screening the reference list of the 12 articles initially selected. The remaining 10 articles were added to provide further input to our SLR, resulting in a research sample of 22 papers. The selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of this SLR.

3. Results

This SLR summarizes the findings of the 22 selected papers that explored the research questions posed in the initial research phase. Table 1 provides a summary of the articles and several characteristics, including research questions or aims, study methodology, participant characteristics (age, diagnosis, language proficiency profile), type and role of AAC, and key findings. Only a limited number of articles exploring the use of AAC in the development of language skills in students with SLDs were identified. This SLR was based on 22 articles, following the purpose of our study to investigate AAC options in the development of students’ language skills in school settings (Supplementary Materials, Page et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Key characteristics of studies included in SLR.

The articles in the sample group included a variety of methodological approaches, the most common being experimental studies (n = 7), followed by exploratory analysis (n = 6), case and multi-case studies (n = 3), theoretical studies (n = 3), cross-sectional analysis (n = 2), and the mixed methods approach (n = 1). The large number of theoretical and experimental studies is probably explained by the need to explore and assess the effectiveness of AAC options in the development of language skills in students with SLDs. All included articles were analysed in terms of factors associated with the impact of AAC on the language skills development of children with SLDs in classroom settings. Out of the total sample of 22 papers, 15 studies (77.27%) focused on improvements in language skills (reading and writing), 22.73% explored the AAC options available for language development and made some recommendations and suggestions, and 13.63% provided information on the impact of AAC on the well-being and psychological health of students with SLDs. The extracted data were summarised using a qualitative meta-summary (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007) and coded deductively according to specific quality criteria. Factors were evaluated for their relevance to our SLR, including the type of AAC, its role, the students’ profile, outcomes (positive, neutral, or negative), language skills, barriers, and strengths.

4. Discussion

In this literature review, we identified common factors associated with the use of AAC in the classroom for students with SLDs. The thematic investigation provided some recurring data on the impact of AAC solutions on students with SLDs, their language development, and recommendations for the selection and use of AAC in classroom settings, as well as the types of support and improvements needed to support the language development of students with SLDs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of themes and subthemes of the impact of AAC on the language skills of students with SLDs.

4.1. Use of AAC with Students with Specific Learning Disorders

To answer our research questions, all 22 papers were reviewed using qualitative thematic analysis to identify patterns across the research samples. However, we identified a lack of studies exploring teachers’ perceptions on, attitudes towards, and preferences regarding AAC systems in our SLR. The selected papers do not provide much insight into teachers’ perceptions of AAC applications and their feedback on the effectiveness of using AAC with students with SLDs.

However, three studies (Barker et al., 2014; Cado et al., 2019; Lindeblad et al., 2019) reported insufficient training on AAC selection, assessment, adaptation, and implementation. Teachers reported facing some issues, such as low digital literacy and poor digital infrastructure (Lindeblad et al., 2019), insufficient training (Barker et al., 2014; Cado et al., 2019), insufficient knowledge of how to integrate assistive technology and AAC into their teaching practice, how to adapt the curriculum (Cado et al., 2019; Lindeblad et al., 2019), and teachers’ reluctance to adopt ACC due to the extra workload (Cado et al., 2019). Another aspect identified in the above papers is the fact that incorporating AAC into teaching is time-consuming. However, teachers reported that students were generally enthusiastic about the use of assistive technology and AAC in the classroom (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007). The increase in motivation and self-confidence was most noticeable in school activities that were predominantly reading-based (Lindeblad et al., 2019; Rousseau et al., 2017).

Preschool teachers reported using PECS as the main AAC tool for communicating with preschool children with complex communication needs, followed by signing and speech-generating devices (Barker et al., 2013). However, they admitted that they used AAC inconsistently and informally. Preschool children with complex communication need to be prompted and encouraged to use AAC in both structured and unstructured settings, as their spontaneous use of AAC is low (Barker et al., 2013).

AAC can be implemented in assessment activities due to its low-pressure focus on speech production and visual-based reading aids, as well as its ability to encourage non-speech responses or limited verbal instructions, which can be challenging for some students (Cleugh & Kirk, 1963; Leckenby & Ebbage-Taylor, 2024). High-tech AAC solutions provide more dynamic settings, immediate feedback, and computerised administration.

4.2. Barriers and Limitations to Using AAC with Students with Specific Learning Disorders

In the context of our second research question—“What types of barriers and limitations have teachers identified when using AAC and AT while working with students?” (RQ1)—only one paper from the research sample explored and identified some barriers and limitations that teachers face when using AAC with students with SLDs. Cado et al. (2019) identified several barriers to integrating AAC into the education of students with SLDs, including (1) a lack of digital infrastructure for children and their families; (2) insufficient human resources, such as teaching assistants, occupational therapists, and teachers available in the classroom to assess, identify, adapt, and implement AAC solutions for students with SLDs; (3) the cost of the equipment; (4) a wide range of AAC solutions being available with specific characteristics; (5) the readiness and ability of the child to learn how to use AAC; and (6) time-consuming implementation.

Similarly, Leckenby and Ebbage-Taylor (2024) identified significant barriers to the integration of AAC in the classroom and emphasised the need for systematic training for educators, better collaboration between professionals, and increased investment in digital tools and resources to support students with speech, language, and communication needs.

4.3. Feasibility and Usability of ACC in Teaching Students with Specific Learning Disorders and Improving Their Language Skills

A larger number of studies (n = 19) provided data on how to assess, use, and adapt AAC to provide better services to students with SLDs, which helped us to answer the second research question, “What features of AAC and AT should be assessed to ensure their feasibility and usability by students with SLDs?” (RQ2).

4.4. Characteristics of Studies of Inclusive Settings and the Role of AAC

AAC options are varied and can be challenging, time-consuming, and sometimes expensive to navigate. It is essential to identify the most efficient AAC system (Flores & Hott, 2022) that the child will find easier and more effective. Some high-tech devices require gross and fine motor skills, which can be problematic for children with SLDs, including those with dyspraxia. This may also explain the low integration of AAC in the learning process of students with SLDs. Motivational factors also need to be considered in relation to teachers’, parents’, and students’ preferences for AAC (Batorowicz et al., 2014). The process of exploring AAC opportunities can take time and effort, and motivational drive is crucial to maintaining the exploration process (Light & McNaughton, 2014; Sevcik et al., 2018).

Several studies, including Barker et al. (Barker et al., 2013), showed a lack of professional training in AAC for teachers and educators. This leads to insufficient knowledge on how to assess the communication needs of their students and identify the best solutions to successfully implement AAC for the development of language and communication skills. The lack of professional training is the reason for the low use of AAC reported by teachers in the learning process of students with SLDs and the relatively small number of studies in this area. Promoting the use of AAC and providing training and support for teachers and parents in the use of AAC is particularly important given the dynamic development of technologically mediated learning environments and the impact of having AAC options available in schools (Barker et al., 2013).

4.5. AAC Assessments to Better Meet the Needs of Students

Researchers such as Tariq and Latif (2016) and Wang et al. (2022) are interested in improving AAC systems and making them more effective for a wider range of users, including students with SLDs. The development of artificial intelligence (AI) has led to a proliferation of AAC solutions, which can make it difficult for teachers and parents to identify the best assistive alternatives. However, all updated versions of AAC systems are based on the Shannon communication device paradigm (Shannon, 1948), which aims to improve communication and language skills.

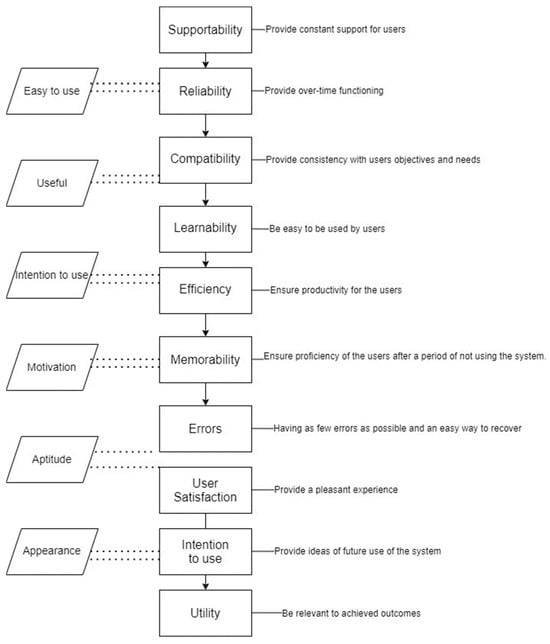

AAC systems undergo an evaluation process to assess their usability and suitability for the specific needs of children with SLDs. AAC devices should be tailored and adapted to the needs of their users. In this study, the focus is on students with SLDs. From the very beginning of AAC systems design, the design process should be learner-centred, and all elements of the tool should support the students’ learning process and help improve their language skills. Tariq and Latif (2016) proposed a technological framework designed to address specific users’ barriers, e.g., (1) phonological barriers, which can be reduced by children becoming familiar with phonemes; (2) reading barriers, which can be reduced by introducing the visualisation of concepts to improve memory skills; and (3) writing barriers, which can be reduced by adapting a learning algorithm to assess students’ writing performance. Some principles for selecting AAC options are presented in Figure 2. Another important element to include in the design of AAC systems is the ability to provide immediate feedback on the progress of students with SLDs to increase motivation for language practice (Tariq & Latif, 2016).

Figure 2.

Checklist for adapting the user experience (based on the System Acceptability Framework proposed by Nielsen (1994)).

4.6. AAC Modalities and Interventions to Improve the Learning Process for Learners with Dyslexia

The use of AAC systems to communicate with peers improved the positive experiences of students with SLDs and increased the number of opportunities for interaction. This is likely to improve children’s language development, which helped us to answer the third research question (How can the process of written language skills development benefit from AAC and AT?—RQ3). This can be attributed to an increased number of communication contexts and opportunities, along with greater exposure to AAC models, as well as teacher modeling during classroom interactions. (Brady et al., 2010). At the same time, AAC was associated with improvements in children’s language outcomes (Joginder Singh & Loo, 2023). The incorporation of AAC systems increased the number of students engaging in communication with partners, which, in turn, provided more opportunities for language practice, as evidenced by improved language scores (Joginder Singh & Loo, 2023).

Reading Fluency and Reading Comprehension. Students with SLDs struggle to comprehend a text due to their inability to master reading at a fluency level. For students with SLDs, the reading process is challenging because reading requires a complex task of recognition/decoding and identifying meaning. Reading comprehension characterises the ability to process a text, fully understand its meaning, and integrate it with what the reader already knows based on a vocabulary stockade and good oral comprehension (Brady et al., 2010). For students with SLDs, the decoding process is impaired, slow, and inaccurate, which is reflected in their reading comprehension.

AAC systems and AT can assist and facilitate the decoding process by ensuring optimal audio–visual integration and maintaining attention through eye-tracking technology. This “audio-visual integration might improve verbal and visual information processing on working memory, increasing the mental resources that can be devoted to comprehension. This might help readers construct and maintain a situational model of the text information, connecting incoming information with the representation of the previous information in the text with the reader’s own prior knowledge” (Schiavo et al., 2021, p. 883). Therefore, the use of AAC to support reading to improve comprehension is a viable solution. Staels and Van den Broeck (2015) reported in their research that children scored highest on comprehension tasks.

Students with SLD have difficulties choosing the correct spelling from two visually presented homophones. Reading comprehension is enhanced when the reading process is atomized; consequently, technology-assisted reading significantly improves the reading process of people with acquired dyslexia (Caute et al., 2018; Lindeblad et al., 2019) and students with SLDs (Al-Thanyyan & Azmi, 2021; Lindeblad et al., 2019; Schiavo et al., 2021). Reading-aloud techniques (i.e., GARY, an eye-tracking-enhanced read-aloud tool) improved the reading comprehension of students with SLDs (dyslexia) by 24% on a reading comprehension standardized instrument (Alqahtani, 2023; Schiavo et al., 2021). Allowing readers to control the pace of reading by linking it to eye gaze reduces the reading effort for students with SLDs, improving their reading experience and their reading comprehension outcomes (Gough & Tunmer, 1986; Hall-Mills et al., 2022; Keelor et al., 2023). AAC systems assist students with SLDs in reading tasks by simplifying text to reduce its complexity and improve readability and comprehension, making the reading process less effortful (Paetzold & Specia, 2017). Augmenta11y is an application that can assist students with SLD in reading and listening activities, thereby improving their overall language competences (Gupta et al., 2021). Improved reading skills lead to greater openness and willingness to learn. Studies suggest that text simplification applications are effective tools for supporting students with SLDs and with low literacy skills (Al-Thanyyan & Azmi, 2021).

Naming Tasks for Vocabulary Building. Vocabulary learning for children with communication and language impairment is hindered by comprehension deficits that reduce their engagement in communicative contexts and limit their opportunities to practise new words (Deliberato et al., 2018). “Limited symbol vocabulary is often a barrier to communicative development” (Sevcik et al., 2018, p. 9). The use of AAC helps children to name objects at an increased rate; however, in real-life conversations, children rely on adults to identify and select the missing word and to support vocabulary building (Deliberato et al., 2018). Another study (Sevcik et al., 2018) presented evidence that students with developmental disabilities and language delays can learn new words and build up their vocabulary (symbol–referent relationships) using AAC (Blissymbols and computer-based symbol sets of lexigrams). However, the use of AAC may raise concerns about the impact on children’s spontaneous engagement with more competent communicative companions, thereby hindering vocabulary development through the construction of meaning in natural communicative contexts that are more relevant. Other studies showed that text-to-speech software had no significant main effect on the item-type naming task (target vs. homophone) (Staels & Van den Broeck, 2015). However, the use of a technology-based system of symbols can be efficient in increasing students’ vocabulary and in natural communicative interactions (Sevcik et al., 2018).

Spelling Task. Share (1999) proposes a self-teaching paradigm, where AAC provides tools for learners and communicators to improve their communication skills through independent learning and practice, not in a formal setting but within more natural speech conditions.

Phonological Representations. Phonological representation consists of the morphemic composition of a word and the phonemic composition of the morphemes in a specific language, and is the basis for inner speech construction, along with semantic and syntactic representations (Alderson-Day & Fernyhough, 2015; Share, 1999). An AAC tool for speech output in a speech-generating device was proven to support the use of phonological forms and is used to promote verbal labelling in adults with disabilities (Dukhovny & Soto, 2013), particularly those who can use their short-term memory for phonological encoding.

Expressive Syntax. Findings from the research conducted by King et al. (2015) provide evidence that AAC can support and provide tools for the dynamic assessment of expressive syntax, such as evaluating children’s ability to sequence simple, rule-based messages using graphic symbols. Assessments performed through AAC systems are significantly enriched, making the process dynamic and more accurate in predicting future language performance, even in the production of expressive syntax and assisted semantic–syntactic structure formation.

Orthograph Task. The overall proportion of correct choices on the orthographic choice task and the proportion of completely correctly spelled target words in the spelling task of children in the experimental condition of a study conducted by Staels and Van den Broeck (2015) were reported to be significantly higher when using text-to-speech software—“well beyond chance” (Staels & Van den Broeck, 2015, p. 46). A positive relationship was found between the decoding ability of students with SLDs and the level of orthographic awareness.

Writing Skills. There is evidence (Rousseau et al., 2017) of gender differences regarding the impact of AAC on spelling self-efficacy and writing self-perception, with better results for boys. Therefore, boys are more likely to use technological support, which improves their sense of self-efficacy in writing, but increases the three dimensions of anxiety in assessments (social depreciation, cognitive blockage, and body tension) (Rousseau et al., 2017). The difficulties and scores regarding cognitive blockage are interpreted as a processing difficulty for students with SLDs and poor motor skills (Toffalini et al., 2017) due to the dual task of written production and the use of AAC tools (Rousseau et al., 2017). In the long term, technological support seems to contribute to subjective well-being by improving the sense of self-efficacy in writing for students with SLDs, regardless of their gender (Rousseau et al., 2017; Schaur & Koutny, 2024). However, in a study by Lindeblad et al. (2017), assistive technology had no impact on students’ self-esteem.

5. Conclusions

This SLR examined practices and key intervention strategies that use AAC tools to support students with SLDs. The findings provide direct insights into the research questions, highlighting both the potential and limitations of AAC in educational settings.

In relation to RQ1 (What barriers and limitations do teachers identify when using AAC and AT with students with SLDs?), this review found that while AAC systems can be effectively integrated into interventions, successful implementation often depends on addressing barriers, such as limited teacher training and a lack of tailored resources. These challenges highlight the importance of equipping educators and parents with the necessary knowledge and skills to implement AAC tools effectively.

For RQ2 (What features of AAC and AT should be assessed to ensure feasibility and usability by students with SLDs?), the findings emphasise the importance of selecting AAC systems that are tailored to the individual needs of students. As AAC technologies become increasingly diverse, understanding their usability and adaptability to specific learning contexts is essential. Teachers and carers need to be empowered to assess and select tools that meet the individual cognitive and linguistic needs of students.

In response to RQ3 (How can the process of developing written language skills benefit from AAC or AT?), this review shows that AAC systems can significantly enhance language development by reducing barriers and promoting inclusive learning environments. AAC has been shown to support the development of critical skills, such as vocabulary, spelling, phonological awareness, orthography, and reading comprehension. By integrating AAC into interventions, students who struggle with traditional methods can benefit from additional scaffolding to improve their written and oral language skills.

While these findings highlight the potential of AAC tools in meeting the language development needs of students with SLDs, this review also identifies significant gaps in the literature. There is limited evidence on how AAC systems are used in the classroom and how they can be scaled to meet wider educational goals. This gap highlights the need for more evidence-based research to develop practical, scalable strategies for integrating AAC into inclusive learning environments.

As the availability of AAC options continues to grow, teachers and parents should acquire specific knowledge to identify appropriate AAC systems to accommodate and meet the educational needs of students with SLDs (McCall et al., 2022). The urgent need for evidence-based intervention is reinforced by the lack of studies on the use of AAC in the classroom. AAC has been shown to reduce barriers to language skills development by fostering inclusive learning environments and providing scaffolding for students struggling with traditional methods of instruction. This review indicates that AAC can enhance language acquisition and support broader educational goals for students with SLDs. This SLR revealed some relevant data on the AAC systems available to students with SLDs that can enhance language acquisition, reduce barriers to language skills development and learning, and create a more inclusive environment in schools.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

According to Staels and Van den Broeck (2015), the use of text-to-speech software is recommended only to assist students with SLDs to compensate for poor reading skills. They discourage the use of text-to-speech software in the early years in favour of naturalistic reading experiences with the active participation of students with SLDs. Other researchers have raised concerns about reading-aloud tools that fail to support students by not keeping track of the text being visually processed by the reader, which can lead to incongruence between what the student reads and what they hear (Schiavo et al., 2021). However, multimodality is recommended, and the simultaneous listening to and reading of text improves comprehension (Curtis et al., 2022). Similarly, Mastrothanasis et al. (2023) highlighted the importance of interactive and engaging strategies like Readers’ Theatre in fostering reading skill development, emphasizing that active participation enhances comprehension and fluency.

Some limitations of this SLR should be noted. First, this SLR relied on a relatively small number of studies that addressed the use of AAC with students with SLDs, and some implications were discussed for studies conducted with students or adults with complex communication needs. Another limitation relates to the unlikelihood of a study reporting negative or neutral effects of AAC on children’s language development. Based on this SLR, further research should focus more on exploring modalities that facilitate peer interactions and create opportunities for engagement in natural communicative settings for students with SLDs, with AAC as a support tool to promote language and dialogical skills. There is a need to conduct research to develop more effective AAC systems to support literacy and address the comprehension challenges posed by different language impairments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci15020170/s1.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author reports no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdelraouf, E. R., Kilany, A., Hashish, A. F., Gebril, O. H., Helal, S. I., Hasan, H. M., & Nashaat, N. H. (2018). Investigating the influence of ubiquinone blood level on the abilities of children with specific learning disorder. Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery, 54(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dababneh, K. A., & Al-Zboon, E. K. (2022). Using assistive technologies in the curriculum of children with specific learning disabilities served in inclusion settings: Teachers’ beliefs and professionalism. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 17(1), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderson-Day, B., & Fernyhough, C. (2015). Inner speech: Development, cognitive functions, phenomenology, and neurobiology. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 931–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, S. S. (2023). Ipad Text-to-Speech and Repeated Reading to Improve Reading Comprehension for Students with SLD. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 39(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thanyyan, S. S., & Azmi, A. M. (2021). Automated Text Simplification. ACM Computing Surveys, 54(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Andzik, N. R., & Chung, Y. C. (2022). Augmentative and alternative communication for adults with complex communication needs: A review of single-case research. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 43(3), 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R. M., Akaba, S., Brady, N. C., & Thiemann-Bourque, K. (2013). Support for AAC use in preschool, and growth in language skills, for young children with developmental disabilities. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 29(4), 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, R. M., Bridges, M. S., & Saunders, K. J. (2014). Validity of a non-speech dynamic assessment of phonemic awareness via the alphabetic principle. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30(1), 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batorowicz, B., Campbell, F., Von Tetzchner, S., King, G., & Missiuna, C. (2014). Social participation of school-aged children who use communication aids: The views of children and parents. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30(3), 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazeley, P. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: Practical strategies. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Benney, C. M., Cavender, S. C., McClain, M. B., Callan, G. L., & Pinkelman, S. E. (2022). Adding Mindfulness to an Evidence-Based Reading Intervention for a Student with SLD: A Pilot Study. Contemporary School Psychology, 26(3), 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukelman, D. R., & Light, J. C. (2020). Augmentative & alternative communication. Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (5th ed.). Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, N. C., Herynk, J. W., & Fleming, K. (2010). Communication input matters: Lessons from prelinguistic children learning to Use AAC in preschool environments. Early Childhood Services, 4(3), 141. [Google Scholar]

- Broomfield, K., Harrop, D., Jones, G. L., Sage, K., & Judge, S. (2022). A qualitative evidence synthesis of the experiences and perspectives of communicating using augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 19(5), 1802–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burac, M. A. P., & Dela Cruz, J. (2020). Development and usability evaluation on individualized reading enhancing application for dyslexia (IREAD): A mobile assistive application. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 803(1), 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, S. P. L., Finak, P., Henderson, J. T., Gaurav, N., Batorowicz, B., Pinder, S. D., & Davies, T. C. (2023). Models and frameworks for guiding assessment for aided Augmentative and Alternative communication (AAC): A scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 19(4), 1758–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cado, A., Nicli, J., Bourgois, B., Vallée, L., & Lemaitre, M. P. (2019). Assessing assistive technology requirements in children with written language disorders. A decision tree to guide counseling. Archives de Pediatrie, 26(1), 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caute, A., Cruice, M., Marshall, J., Monnelly, K., Wilson, S., & Woolf, C. (2018). Assistive technology approaches to reading therapy for people with acquired dyslexia. Aphasiology, 32(1), 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleugh, M. F., & Kirk, S. A. (1963). Educating exceptional children. British Journal of Educational Studies, 12(1), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, H., Neate, T., & Vazquez Gonzalez, C. (2022, October 23–26). State of the art in AAC: A systematic review and taxonomy. ASSETS 2022—Proceedings of the 24th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Athens, Greece. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliberato, D., Jennische, M., Oxley, J., Nunes, L. R. D. D. P., Walter, C. C. D. F., Massaro, M., Almeida, M. A., Stadskleiv, K., Basil, C., Coronas, M., Smith, M., & von Tetzchner, S. (2018). Vocabulary comprehension and strategies in name construction among children using aided communication. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 34(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhingra, K., Aggarwal, R., Garg, A., Pujari, J., & Yadav, D. (2024). Mathlete: An adaptive assistive technology tool for children with dyscalculia. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 19(1), 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukhovny, E., & Soto, G. (2013). Speech generating devices and modality of short-term word storage. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 29(3), 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M. M., & Hott, B. L. (2022). Introduction to a Special Series on Single Research Case Design: Information for Peer Reviewers and Researchers Designing Behavioral Interventions for Students With SLD. Learning Disability Quarterly, 07319487221085267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T., Aflatoony, L., & Leonard, L. (2021, October 22–25). Augmenta11y: A reading assistant application for children with dyslexia. Proceedings of the 23rd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (pp. 1–3), New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Mills, S., Marante, L., Tonello, B., & Johnson, L. (2022). Improving Reading Comprehension for Adolescents With Language and Learning Disorders. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 44(1), 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, J. G. M., Keulers, E. H. H., Feron, F. J. M., Wassenberg, R., Jolles, J., & Vles, J. S. H. (2007). Subtypes of learning disabilities: Neuropsychological and behavioural functioning of 495 children referred for multidisciplinary assessment. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 16(8), 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyfield, C., Caron, J., Lorah, E., & Norton, B. (2023). Effect of Low-Tech Augmentative and Alternative Communication Intervention on Intentional Triadic Gaze as Alternative Access by School-Age Children With Multiple Disabilities. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 54(3), 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joginder Singh, S., & Loo, Z. L. (2023). The use of augmentative and alternative communication by children with developmental disability in the classroom: A case study. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 18(8), 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keelor, J. L., Creaghead, N. A., Silbert, N. H., Breit, A. D., & Horowitz-Kraus, T. (2023). Impact of text-to-speech features on the reading comprehension of children with reading and language difficulties. Annals of Dyslexia, 73(3), 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M. J., Thomas, C. N., Meyer, J. P., Alves, K. D., & Lloyd, J. W. (2014). Using evidence-based multimedia to improve vocabulary performance of adolescents with ld: A udl approach. Learning Disability Quarterly, 37(2), 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodeir, M. S., El-Sady, S. R., & Mohammed, H. A. E. R. (2020). The prevalence of psychiatric comorbid disorders among children with specific learning disorders: A systematic review. Egyptian Journal of Otolaryngology, 36(1), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M. R., Binger, C., & Kent-Walsh, J. (2015). Using dynamic assessment to evaluate the expressive syntax of children who use augmentative and alternative communication. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leckenby, K., & Ebbage-Taylor, M. (2024). AAC and aided language in the classroom: Breaking down barriers for learners with speech, language and communication needs. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Leeds-Hurwitz, W. (1993). Semiotics and communication: Signs, codes, cultures. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lerga, R., Candrlic, S., & Jakupovic, A. (2021, April 23–25). A review on assistive technologies for students with dyslexia. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (pp. 64–72), Online Streaming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2014). Communicative competence for individuals who require augmentative and alternative communication: A new definition for a new era of communication? AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeblad, E., Nilsson, S., Gustafson, S., & Svensson, I. (2017). Assistive technology as reading interventions for children with reading im-pairments with a one-year follow-up. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 12(7), 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeblad, E., Nilsson, S., Gustafson, S., & Svensson, I. (2019). Self-concepts and psychological health in children and adolescents with reading difficulties and the impact of assistive technology to compensate and facilitate reading ability. Cogent Psychology, 6(1), 1647601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrothanasis, K., Kladaki, M., & Andreou, A. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Readers’ Theatre impact on the development of reading skills. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 4, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, J., van der Stelt, C. M., DeMarco, A., Dickens, J. V., Dvorak, E., Lacey, E., Snider, S., Friedman, R., & Turkeltaub, P. (2022). Distinguishing semantic control and phonological control and their role in aphasic deficits: A task switching investigation. Neuropsychologia, 173, 108302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miciak, J., Ahmed, Y., Capin, P., & Francis, D. J. (2022). The reading profiles of late elementary English learners with and without risk for dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia, 72(2), 276–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A., Estarli, M., Barrera, E. S. A., Martínez-Rodríguez, R., Baladia, E., Agüero, S. D., Camacho, S., Buhring, K., Herrero-López, A., Gil-González, D. M., Altman, D. G., Booth, A., … Whitlock, E. (2016). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Revista Espanola de Nutricion Humana y Dietetica, 20(2), 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Joint Committee for the Communicative Needs of Persons with Severe Disabilities. (1992). Guidelines for meeting the communication needs of persons with severe disabilities (Supplement, 7). ASHA. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. (1994). Usability engineering. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paetzold, G. H., & Specia, L. (2017). A survey on lexical simplification. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 60, 549–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Chou, R. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, M. V., Mahaffy, K., Vlahcevic, K., Wolfman, E., Erbeli, F., Richlan, F., & Landi, N. (2022). Reading intervention and neuroplasticity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of brain changes associated with reading intervention. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 132, 465–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluye, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., & Johnson-Lafleur, J. (2009). A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(4), 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rello, L., Bayarri, C., Otal, Y., & Pielot, M. (2014, October 20–22). A computer-based method to improve the spelling of children with dyslexia. ASSETS14—Proceedings of the 16th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Rochester, NY, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmer, O., Doignon-Camus, N., Audusseau, J., Trautmann, S., Chaillou, A. C., & Popa-Roch, M. (2022). Removing the academic framing in student evaluations improves achievement in children with dyslexia: The mediating role of self-judgement of competence. Dyslexia, 28(3), 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, N., Dumont, M., Paquin, S., Desmarais, M., Stanké, B., & Boyer, P. (2017). Le sentiment de bien-être subjectif d’élèves dyslexiques et dysorthographiques en situation d’écriture: Quel apport des technologies d’aide? ANAE—Approche Neuropsychologique Des Apprentissages Chez l’Enfant, 29(148), 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer Publishing Company. Available online: https://parsmodir.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/MetaSynBook.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Schaur, M., & Koutny, R. (2024, July 8–12). Dyslexia, reading/writing disorders: Assistive technology and accessibility. Computers Helping People with Special Needs: 19th International Conference, ICCHP 2024 (pp. 269–274), Linz, Austria. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavo, G., Mana, N., Mich, O., Zancanaro, M., & Job, R. (2021). Attention-driven read-aloud technology increases reading comprehension in children with reading disabilities. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(3), 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevcik, R. A., Barton-Hulsey, A., Romski, M. A., & Hyatt Fonseca, A. (2018). Visual-graphic symbol acquisition in school age children with developmental and language delays. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 34(4), 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A Mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27(3), 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Share, D. L. (1999). Phonological recoding and orthographic learning: A direct test of the self-teaching hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 72(2), 95–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staels, E., & Van den Broeck, W. (2015). Orthographic learning and the role of text-to-speech software in dutch disabled readers. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, R., & Latif, S. (2016). A mobile application to improve learning performance of dyslexic children with writing difficulties. Educational Technology and Society, 19(4), 402–409. [Google Scholar]

- Toffalini, E., Giofrè, D., & Cornoldi, C. (2017). Strengths and Weaknesses in the Intellectual Profile of Different Subtypes of Specific Learning Disorder: A Study on 1049 Diagnosed Children. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(2), 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Muthu, B. A., & Sivaparthipan, C. B. (2022). Smart assistance to dyslexia students using artificial intelligence based augmentative alternative communication. International Journal of Speech Technology, 25(2), 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. G., Moxley, J. H., Tighe, E. L., & Wagner, R. K. (2018). Does use of text-to-speech and related read-aloud tools improve reading comprehension for students with reading disabilities? A meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51(1), 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).