A Cluster Analysis of Identity Processing Styles and Educational and Psychological Variables Among TVET Students in the Nyanza Region of Kenya

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Identity Theories

2.1.2. Berzonsky’s Model of Identity Processing Styles

2.1.3. Educational and Psychological Correlates of Identity Processing

2.2. Study Aims

- (i)

- What are the relationships between identity processing styles and educational variables such as academic motivation, procrastination, and achievement among TVET students?

- (ii)

- How do psychological factors, including self-efficacy, life orientation, and smartphone addiction, relate to the identity processing styles of automotive engineering students?

- (iii)

- Can distinct student profiles be identified through cluster analysis based on identity processing styles and their associated psychological and educational variables?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Revised Identity Style Inventory (ISI-5)

3.2.2. Academic Motivation Scale

3.2.3. Academic Performance Scale

3.2.4. Academic Procrastination Scale

3.2.5. General Self-Efficacy Scale

3.2.6. Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R)

3.2.7. Smartphone Addiction Scale—Short Version (SAS-SV)

3.2.8. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

3.3. Ethical Consideration

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Relationships

4.2. K-Means Clustering

5. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Questionnaire for Automotive Engineering Students

- Course of study…

- Age…

- Sex…

- Your Institution…

- (a)

- Identity Style Inventory Scales

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Defuse-avoidant items: Cronbach’s alpha: 0.85 | ||||||

| 1 | When personal problems arise, I try to delay acting as long as possible | |||||

| 2 | I’m not sure where I’m heading in my life; I guess things will work themselves out | |||||

| 3 | My life plans tend to change whenever I talk to different people | |||||

| 4 | Who I am changes from situation to situation | |||||

| 5 | I try not to think about or deal with problems as long as I can | |||||

| 6 | I try to avoid personal situations that require me to think a lot and deal with them on my own | |||||

| 7 | When I have to make a decision, I try to wait as long as possible to see what will happen | |||||

| 8 | It doesn’t pay to worry about values in advance; I decide things as they happen | |||||

| 9 | I am not thinking about my future now, it is still a long way off | |||||

| Informational items: Cronbach’s alpha: 0.96 | ||||||

| 1 | When making important decisions, I like to spend time thinking about my options | |||||

| 2 | When facing a life decision, I take into account different points of view before making a choice | |||||

| 3 | It is important for me to obtain and evaluate information from a variety of sources before I make important life decisions | |||||

| 4 | When making important decisions, I like to have as much information as possible | |||||

| 5 | When facing a life decision, I try to analyze the situation to understand it | |||||

| 6 | Talking to others helps me explore my personal beliefs | |||||

| 7 | I handle problems in my life by actively reflecting on them | |||||

| 8 | I periodically think about and examine the logical consistency between my values and life goals | |||||

| 9 | I spend a lot of time reading or talking to others trying to develop a set of values that makes sense to me | |||||

| Normative items: Cronbach’s alpha: 0.92 | ||||||

| 1 | I automatically adopt and follow the values I was brought up with | |||||

| 2 | I think it is better to adopt a firm set of beliefs than to be open-minded | |||||

| 3 | I think it’s better to hold on to fixed values rather than to consider alternative value systems | |||||

| 4 | When I make a decision about my future, I automatically follow what close friends or relatives expect from me | |||||

| 5 | I prefer to deal with situations in which I can rely on social norms and standards | |||||

| 6 | I have always known what I believe and don’t believe; I never really have doubts about my beliefs | |||||

| 7 | I never question what I want to do with my life because I tend to follow what important people expect me to do | |||||

| 8 | When others say something that challenges my personal values or beliefs, I automatically disregard what they have to say | |||||

| 9 | I strive to achieve the goals that my family and friends hold for me | |||||

| Adopted from Berzonsky et al. (2013, p. 897). | ||||||

- (b)

- Self-Efficacy Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough | |||||

| 2 | If someone opposes me, I can find the means and ways to get what I want | |||||

| 3 | It is easy for me to stick to my aims and accomplish my goals | |||||

| 4 | I am confident that I can deal efficiently with unexpected events | |||||

| 5 | Thanks to my resourcefulness, I know how to handle unforeseen situations | |||||

| 6 | I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort | |||||

| 7 | I can remain calm when facing difficulties because I can rely on my coping abilities | |||||

| 8 | When I am confronted with a problem, I can usually find several solutions | |||||

| 9 | If I am in trouble, I can usually think of a solution | |||||

| 10 | I can usually handle whatever comes my way | |||||

| Adopted from Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995). Cronbach’s alpha: 0.92. | ||||||

- (c)

- Academic Motivation Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | For the pleasure I experience when I discover new things never seen before. | |||||

| 2 | Because my studies allow me to continue to learn about many things that interest me | |||||

| 3 | For the pleasure that I experience while I am surpassing myself in one of my personal accomplishments. | |||||

| 4 | Because college allows me to experience personal satisfaction in my quest for excellence in my studies | |||||

| 5 | For the pleasure that I experience when I read interesting authors. | |||||

| 6 | For the pleasure that I experience when I feel completely absorbed by what certain authors have written | |||||

| 7 | Because I think that a college education will help me better prepare for the career I have chosen | |||||

| 8 | Because eventually, it will enable me to enter the job market in a field that I like | |||||

| 9 | Because of the fact that when I succeed in college I feel important | |||||

| 10 | Because I want to show myself that I can succeed in my studies | |||||

| 11 | In order to obtain a more prestigious job later on. | |||||

| 12 | In order to have a better salary later on | |||||

| 13 | I can’t see why I go to college and frankly, I couldn’t care less | |||||

| 14 | I don’t know; I can’t understand what I am doing in school | |||||

| Adopted from (Kotera et al., 2021). Cronbach’s alpha: 0.89. | ||||||

- (d)

- Life Orientation Test

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | In uncertain times, I usually expect the best | |||||

| 2 | It’s easy for me to relax | |||||

| 3 | If something can go wrong for me it will | |||||

| 4 | I am always optimistic about my future | |||||

| 5 | I enjoy my friends a lot | |||||

| 6 | It is important for me to keep busy | |||||

| 7 | I hardly ever expect things to go my way | |||||

| 8 | I don’t get upset too easily | |||||

| 9 | I rarely count on good things happening to me | |||||

| 10 | Overall, I expect more good things to happen to me than bad | |||||

| Adopted from Scheier et al. (1994). Cronbach’s alpha: 0.77. | ||||||

- (e)

- Academic Achievement Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | I made myself ready in all my subjects | |||||

| 2 | I pay attention and listen during every discussion. | |||||

| 3 | I want to get good grades in every subject. | |||||

| 4 | I actively participate in every discussion. | |||||

| 5 | I start papers and projects as soon as they are assigned. | |||||

| 6 | I enjoy homework and activities because they help me improve my skills in every subject. | |||||

| 7 | I exert more effort when I do difficult assignments. | |||||

| 8 | Solving problems is a useful hobby for me. | |||||

| Adopted from Birchmeier, Grattan, Hornbacher, and McGregory. Cronbach’s alpha: 0.94. | ||||||

- (f)

- Smartphone Addiction Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | Missing planned work due to smartphone use | |||||

| 2 | Having a hard time concentrating in class, while doing assignments, or while working due to smartphone use | |||||

| 3 | Feeling pain in the wrists or at the back of the neck while using a smartphone | |||||

| 4 | Won’t be able to stand not having a smartphone | |||||

| 5 | I feel impatient and fretful when I am not holding my smartphone | |||||

| 6 | Having my smartphone in my mind even when I am not using it | |||||

| 7 | I will never give up using my smartphone even when my daily life is already greatly affected by it | |||||

| 8 | I constantly check my smartphone so as not to miss conversations between other people on Twitter or Facebook | |||||

| 9 | Using my smartphone longer than I had intended | |||||

| 10 | The people around me tell me that I use my smartphone too much. | |||||

| Adopted from (Kwon et al., 2013). Cronbach’s alpha: 0.93. | ||||||

- (g)

- Academic Procrastination Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | I put off projects until the last minute. | |||||

| 2 | I know I should work on schoolwork, but I just don’t do it. | |||||

| 3 | I get distracted by other, more fun, things when I am supposed to work on schoolwork. | |||||

| 4 | When given an assignment, I usually put it away and forget about it until it is almost due. | |||||

| 5 | I frequently find myself putting important deadlines off. | |||||

| Adopted from (Yockey, 2016). Cronbach’s alpha: 0.92. | ||||||

- (h)

- Satisfaction With Life Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| 1 | In most case my life is close to my ideal. | |||||||

| 2 | The conditions of my life are excellent. | |||||||

| 3 | I am satisfied with my life. | |||||||

| 4 | So far I have gotten the important things I want in life. | |||||||

| 5 | If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. | |||||||

| Source: (Diener et al., 1985). Cronbach’s alpha: 0.75. | ||||||||

References

- Achuodho, H. O., & Pikó, B. F. (2024). Experiencing online training and educational inequality in TVET delivery among trainers and trainees in Kenya during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Hungarian Educational Research Journal, 14(4), 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademtsu, J. T., & Pathak, P. (2023). A review on the fhallenges of gashion students’ training based on curriculum structure of technical universities in Ghana. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 12(11), 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1978). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1(4), 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares, & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (vol. 5, pp. 307–337). Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Barasa, O., Manasi, E., & Wepukhulu, R. (2023). Trainers’ pedagogical competence in technical and vocational education and training institutions in Bungoma County, Kenya. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 8(2), 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, M. D. (1992). Identity style and coping strategies. Journal of Personality, 60(4), 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzonsky, M. D., & Ferrari, J. R. (2009). A diffuse-avoidant identity processing style: Strategic avoidance or self-confusion? Identity, 9(2), 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, M. D., & Kuk, L. S. (2005). Identity style, psychosocial maturity, and academic performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(1), 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, M. D., Soenens, B., Luyckx, K., Smits, I., Papini, D. R., & Goossens, L. (2013). Development and validation of the revised Identity Style Inventory (ISI-5): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Psychological Assessment, 25(3), 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birchmeier, C., Grattan, E., Hornbacher, S., & McGregory, C. (2015). Academic performance questionnaire. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/57247883/_PDF_Academic_Performance_Questionnaire (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Bouizegarene, N., Bourdeau, S., Leduc, C., Gousse-Lessard, A., Houlfort, N., & Vallerand, R. J. (2018). We are our passions: The role of identity processes in harmonious and obsessive passion and links to optimal functioning in society. Self and Identity, 17(1), 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadely, H. S., Pittman, J. F., Kerpelman, J. L., & Adler-Baeder, F. (2011). The role of identity styles and academic possible selves on academic Outcomes for high school students. Identity, 11(4), 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Vecchione, M., Alessandri, G., Gerbino, M., & Barbaranelli, C. (2011). The contribution of personality traits and self-efficacy beliefs to academic achievement: A longitudinal study: Personality traits, self-efficacy beliefs and academic achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(1), 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, P., Jiang, Z., Xiao, X., Liang, X., Chen, J., & Chiang, F. (2024). Exploring the entrepreneurial self-efficacy of STEM students within the context of an informal STEM education programme. Research in Science Education, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., Luyckx, K., & Meeus, W. (2008). Identity formation in early and middle adolescents from various ethnic groups: From three dimensions to five statuses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(8), 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, R., Orçan, F., & Altun, F. (2020). Investigating the relationship between life satisfaction and academic self-efficacy on college students’ organizational identification. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 7(1), 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, M., Galand, B., & Frenay, M. (2017). Transition from high school to university: A person-centered approach to academic achievement. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 32(1), 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dontre, A. J. (2020). The influence of technology on academic distraction: A review. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(3), 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, D. B., & Kubota, M. (2015). Hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and academic achievement: Distinguishing constructs and levels of specificity in predicting college grade-point average. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, J. R., & Scher, S. J. (2000). Toward an understanding of academic and nonacademic tasks procrastinated by students: The use of daily logs. Psychology in the Schools, 37, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, C. G., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Gallardo-Pujol, D. (2009). Factor analysis with ordinal indicators: A monte Carlo study comparing DWLS and ULS estimation. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 16(4), 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffoor, A., & Van der Bijl, A. (2019). Factors influencing the intention of students at a selected TVET college in the Western Cape to complete their National Certificate (Vocational) Business Studies programme. Journal of Vocational, Adult and Continuing Education and Training, 2(2), 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hansson, E., & Sjöberg, J. (2019). Making use of students’ digital habits in higher education: What they already know and what they learn. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. (14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E. H., Alasmari, A., & Ahmed, E. Y. (2015). Influences of self-efficacy as predictors of academic achievement. A case Study of special education students—University of Jazan. International Journal of Educational Research, 3, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Hejazi, E., Shahraray, M., Farsinejad, M., & Asgary, A. (2009). Identity styles and academic achievement: Mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Social Psychology of Education, 12(1), 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, A. W., Hoy, W. K., & Kurz, N. M. (2008). Teacher’s academic optimism: The development and test of a new construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(4), 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, T. G., & Dembo, M. H. (2004). The relationship of self-efficacy, identity style, and stage of change with academic self-regulation. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 35(1), 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., Krawchuk, L. L., & Rajani, S. (2008). Academic procrastination of undergraduates: Low self-efficacy to self-regulate predicts higher levels of procrastination. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33(4), 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarraju, M., & Dial, C. (2014). Academic identity, self-efficacy, and self-esteem predict self-determined motivation and goals. Learning and Individual Differences, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarraju, M., & Nadler, D. (2013). Self-efficacy and academic achievement: Why do implicit beliefs, goals, and effort regulation matter? Learning and Individual Differences, 25, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y., Conway, E., & Green, P. (2021). Construction And factorial validation of a short version of the academic motivation scale. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 51(2), 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A. W., Orehek, E., Higgins, E. T., Pierro, A., & Shalev, I. (2010). Modes of self-regulation: Assessment and locomotion as independent determinants in goal pursuit. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of Personality and Self-Regulation (pp. 375–402). Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-7712-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kunwar, J. B. (2021). The influence of culture on collaborative learning practices in higher education. Journal of Intercultural Management, 13(2), 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M., Kim, D., Cho, H., & Yang, S. (2013). The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE, 8(12), e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leader, S. (2010). Relating identity processing styles and self-efficacy to academic achievement in first-year university Students. Faculty of Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, A. C., Davis, L. L., & Kraemer, H. C. (2011). The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(5), 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Goossens, L., Beyers, W., & Missotten, L. (2011). Processes of personal identity formation and evaluation. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 77–98). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-7987-2. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, S., Freeman, E., Skues, J. L., & Wise, L. (2022). Shaping the self through education: Exploring the links between educational identity statuses, appraisals of control and value, and achievement emotions. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 37(4), 1285–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meens, E. E., Bakx, A. W., Klimstra, T. A., & Denissen, J. J. (2018). The association of identity and motivation with students’ academic achievement in higher education. Learning and Individual Differences, 64, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadi, Z., & Mokhtari, F. H. (2016). Identity styles: Predictors of reading and writing abilities. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 5(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ng, Z. J., Huebner, S. E., & Hills, K. J. (2015). Life satisfaction and academic performance in early adolescents: Evidence for reciprocal association. Journal of School Psychology, 53(6), 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngware, M. W., Ochieng’, V., Kiroro, F., Hungi, N., & Muchira, J. M. (2024). Assessing the acquisition of whole youth development skills among students in TVET institutions in Kenya. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 76(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niittylahti, S., Annala, J., & Mäkinen, M. (2019). Student engagement at the beginning of vocational studies. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 9(1), 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niittylahti, S., Annala, J., & Mäkinen, M. (2021). Student engagement profiles in vocational education and training: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 75(2), 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okelo, O. B., Matere, A., & Syonthi, J. (2021). Assessment of emerging trends in technical, vocational education and training institutions policies in relation to students’ academic achievement in Uasin Gishu County, Kenya. Journal of Research Innovation and Implications in Education, 5(4), 342–351. [Google Scholar]

- Okumu, G. J., & Kenei, J. K. (2023). Factors promoting acquisition of employable skills among students in technical and vocational education and training institutions in Kenya. The Kenya Journal of Technical and Vocational Education and Training, 6, 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Oroni, N., Manasi, E., & Wepukhulu, R. (2023). Trainers’ competence in the knowledge of the subject content in technical vocational education and training institutions in Bungoma County, Kenya. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 9(1), 094–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osidipe, A. (2017). Prospects for TVET in developing skills for work in nigeria. Journal of Education and Practice, 8, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Otiono, N. (2021). Dream delayed or dream betrayed: Politics, youth agency and the mobile revolution in Africa. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines, 55(1), 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, M. (2014). TVET as an important factor in country’s economic development. SpringerPlus, 3(1), K3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pelser, A. M. F., Vaiman, V., & Nagy, S. (2022). The improvement of skills & talents in the workplace. Axiom Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-1-991239-06-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydz, E., & Romaneczko, J. (2022). Identity styles and Readiness to enter into interreligious dialogue: The moderating function of religiosity. Religions, 13(11), 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S., & Zyngier, D. (2012). How motivation influences student engagement: A qualitative case study. Journal of Education and Learning, 1(2), 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sany, S. B. T., Aman, N., Jangi, F., Lael-Monfared, E., Tehrani, H., & Jafari, A. (2023). Quality of life and life satisfaction among university students: Exploring, subjective norms, general health, optimism, and attitude as potential mediators. Journal of American College Health, 71(4), 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M., & Fletcher, D. (2014). Ordinary magic, extraordinary performance: Psychological resilience and thriving in high achievers. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 3(1), 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). General self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). Windsor. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabi, J., & Payne, J. (2013). Effects of identity processing styles on academic achievement of first year university students. International Journal of Educational Management, 27(3), 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, L. (2024). Learning through practice: The experience of secondary school TVET teachers in Chile. International Journal of Training Research, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavinski, T., Bjelica, D., Pavlović, D., & Vukmirović, V. (2021). Academic performance and physical activities as positive factors for life satisfaction among university students. Sustainability, 13(2), 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenens, B., Berzonsky, M. D., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., & Goossens, L. (2005). Identity styles and causality orientations: In search of the motivational underpinnings of the identity exploration process. European Journal of Personality, 19(5), 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, J. (2009). Identity Development throughout the lifetime: An examination of identity development throughout the life-time: An examination of eriksonian Theory. Graduate Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Struyf, A., Hubert, M., & Rousseeuw, P. (1997). Clustering in an object-oriented environment. Journal of Statistical Software, 1(4), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svartdal, F., Dahl, T. I., Gamst-Klaussen, T., Koppenborg, M., & Klingsieck, K. B. (2020). How study environments foster academic procrastination: Overview and recommendations. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 540910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjala, G., Chepkoech, S., & Khatete, I. (2020). Impact of Infrastructure at technical vocational education institutions on human resource development on realization of sustainable development goals in western Kenya. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 11(1), 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wilks, D. S. (2011). Cluster Analysis. In International geophysics (vol. 100, pp. 603–616). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-385022-5. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L., Yao, M., & Liu, H. (2024). Perceived social mobility and smartphone dependence in university students: The roles of hope and family socioeconomic status. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yockey, R. D. (2016). Validation of the short form of the academic procrastination scale. Psychological Reports, 118(1), 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrin, S., Paixão, M., & Panhandeh, A. (2017). Predicting academic performance by identity styles and self-efficacy beliefs (personal and collective) in Iranian high school students. World Science Report, 62, 186–191. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Diffuse-avoidant | (0.85) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Informational | 0.29 ** | (0.96) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. Normative | 0.41 *** | 0.59 *** | (0.92) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4. Academic Performance | 0.15 | 0.65 *** | 0.46 *** | (0.94) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5. Academic Procrastination | 0.46 *** | 0.01 | 0.31 ** | −0.02 | (0.92) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6. Academic Motivation | 0.19 * | 0.73 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.82 *** | −0.08 | (0.89) | - | - | - | - |

| 7. Self-efficacy | 0.16 | 0.73 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.77 *** | 0.01 | 0.80 *** | (0.92) | - | - | - |

| 8. Optimism | −0.05 | 0.37 *** | −0.01 | 0.44 *** | −0.48 *** | −44 *** | 0.32 ** | (0.77) | - | - |

| 9. Smartphone addiction | 0.42 *** | −0.04 | 0.18 | −0.04 | 0.82 *** | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.43 *** | (0.93) | - |

| 10. Satisfaction with life | 0.33 ** | 0.17 | 0.32 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.58 *** | 0.17 | 0.23 * | −0.01 | 0.52 *** | (0.75) |

| Score | 9–45 | 9–45 | 9–45 | 8–40 | 5–25 | 22–70 | 10–50 | 13–30 | 10–50 | 5–25 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.23 (8.59) | 34.14 (10.02) | 29.14 (9.90) | 31.35 (8.05) | 12.68 (5.84) | 52.35 (11.43) | 37.33 (9.61) | 19.97 (3.54) | 26.71 (11.21) | 15.10 (4.48) |

| Skewness | −0.013 | 1.091 | −0.373 | −1.030 | 0.329 | −0.719 | −0.991 | 0.599 | 0.212 | 0.080 |

| Kurtosis | −0.108 | 0.562 | −0.375 | 0.563 | −0.927 | 0.263 | 0.986 | −0.012 | −0.705 | 0.159 |

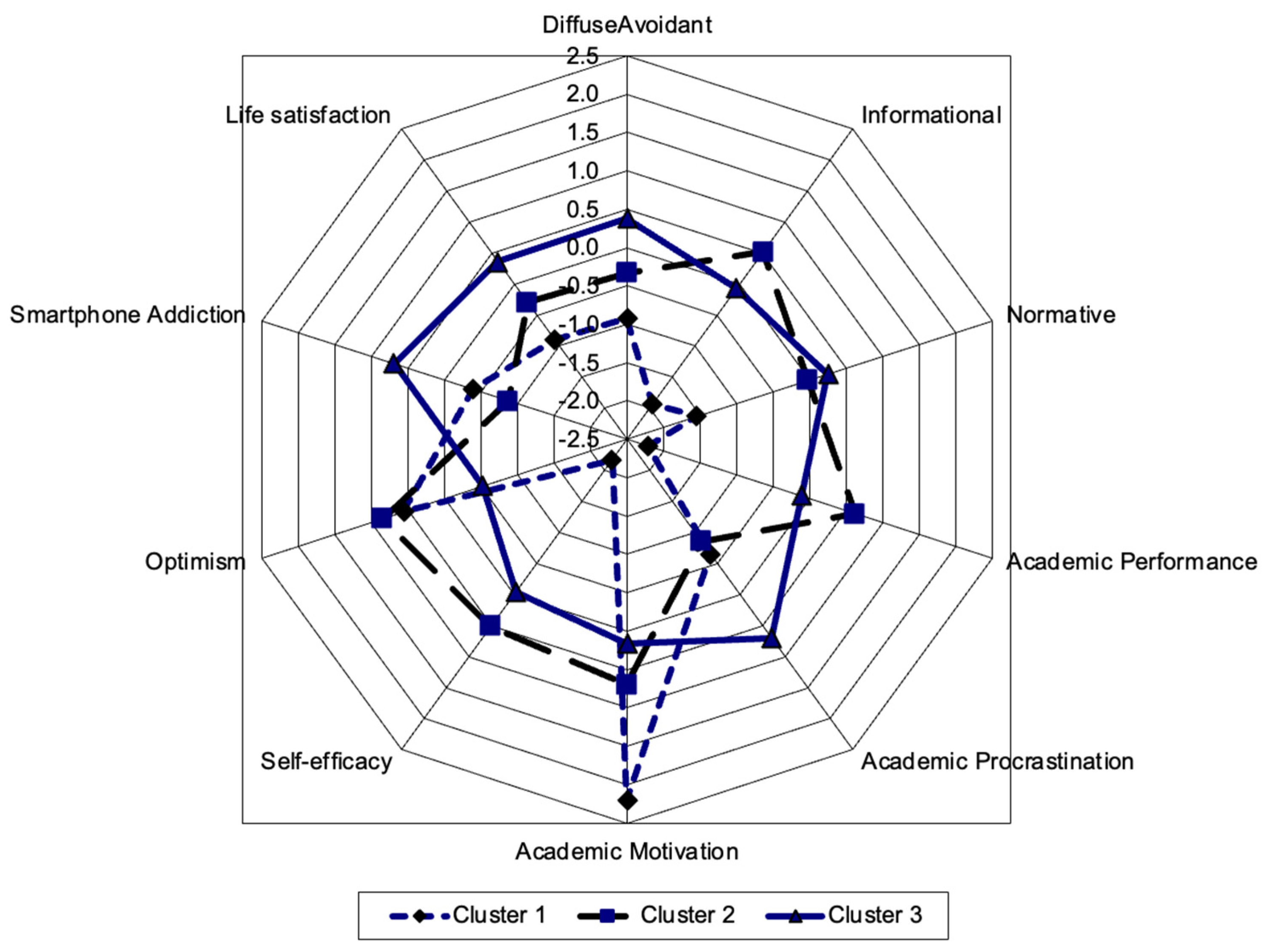

| Cluster 1 Mean (SD) z-Score | Cluster 2 Mean (SD) z-Score | Cluster 3 Mean (SD) z-Score | F-Value | η2p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffuse-avoidant | 18.33 (7.02) −0.92 | 23.31 (8.83) −0.34 | 29.51 (7.08) 0.38 | 12.79 *** | 0.19 |

| Informational | 14.67 (6.54) −1.94 | 39.36 (6.81) 0.52 | 33.41 (8.43) −0.07 | 38.54 *** | 0.42 |

| Normative | 13.89 (7.17) −1.54 | 28.98 (9.59) −0.02 | 31.59 (8.37) 0.25 | 15.90 *** | 0.23 |

| Academic Performance | 13.56 (4.75) −2.21 | 36.45 (3.69) 0.63 | 30.44 (6.35) −0.11 | 69.45 *** | 0.56 |

| Academic Procrastination | 8.89 (3.26) −0.65 | 7.69 (2.52) −0.85 | 16.81 (4.53) 0.71 | 76.00 *** | 0.59 |

| Academic Motivation | 27.11 (5.42) −2.20 | 60.40 (6.17) 0.70 | 50.47 (8.08) −0.16 | 83.03 *** | 0.61 |

| Self-efficacy | 16.44 (8.44) −2.17 | 42.31 (6.03) 0.52 | 36.97 (7.24) −0.04 | 52.16 *** | 0.49 |

| Optimism | 18.00 (1.22) −0.56 | 22.98 (3.32) 0.85 | 18.14 (2.25) −0.52 | 43.39 *** | 0.45 |

| Smartphone addiction | 22.33 (9.64) −0.39 | 16.79 (5.86) −0.88 | 34.44 (8.00) 0.69 | 71.49 *** | 0.57 |

| Satisfaction with life | 11.11 (4.73) −0.89 | 13.60 (4.18) −0.30 | 16.93 (3.98) 0.36 | 37.32 *** | 0.17 |

| Percentage (n) | 8.18% (9) | 38.18% (42) | 53.64% (59) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Achuodho, H.O.; Berki, T.; Piko, B.F. A Cluster Analysis of Identity Processing Styles and Educational and Psychological Variables Among TVET Students in the Nyanza Region of Kenya. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020135

Achuodho HO, Berki T, Piko BF. A Cluster Analysis of Identity Processing Styles and Educational and Psychological Variables Among TVET Students in the Nyanza Region of Kenya. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(2):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020135

Chicago/Turabian StyleAchuodho, Hamphrey Ouma, Tamás Berki, and Bettina F. Piko. 2025. "A Cluster Analysis of Identity Processing Styles and Educational and Psychological Variables Among TVET Students in the Nyanza Region of Kenya" Education Sciences 15, no. 2: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020135

APA StyleAchuodho, H. O., Berki, T., & Piko, B. F. (2025). A Cluster Analysis of Identity Processing Styles and Educational and Psychological Variables Among TVET Students in the Nyanza Region of Kenya. Education Sciences, 15(2), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020135