Abstract

Background: Learning to read is a complex linguistic and cognitive process. Despite the ever-growing body of empirical evidence, the complex knowledge and skills needed to teach all children to read have not been passed to trainee and in-service teachers. Methods: This study examined the delivery and evaluation of a short, intense literacy elective course, with 9 h of learning for trainee primary/elementary teachers, focused on the key knowledge areas of phonemic awareness, phonics instruction, fluency, vocabulary, text comprehension, and reading assessment. An open questionnaire was administered to 16 trainee teachers: they completed this same questionnaire prior to beginning the elective and again after. The questionnaire focused on the understanding of quality reading instruction, at-risk readers, and provision for struggling readers. The data were analyzed using a qualitative interpretational analysis (QIA). Results: The lowest levels of understanding at the outset were in reading fluency instruction and reading assessment: these areas then showed the greatest knowledge development. Importantly, by post test, participants increased access to evidence-based literature and resources. Feedback demonstrated the high value placed by the group on this learning. Conclusions: This approach improved trainee teachers’ content knowledge to teach reading in a short time. Initial Teacher Education should increase its focus on reading, a crucial foundation skill.

1. Introduction

Learning to read is a complex cognitive and linguistic process. Novice learners will be most successful when taught with structured explicit systematic instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics skills along with vocabulary, syntax, fluency, background knowledge, and text comprehension (Moats, 2020; Snow et al., 2024). Furthermore, for teachers, knowledge and skills in the assessment and progress monitoring of reading skills acquisition are essential to ensure that instruction is targeted to meet the needs of the increasing number of struggling readers (Petscher et al., 2020; Seidenberg et al., 2020).

Worldwide, Initial Teacher Education (ITE) has been shown to lack emphasis on these complex areas, and instead continues to focus on multiple literacies or “balanced literacy” (Mccombes-Tolis & Spear-Swerling, 2011; Meeks et al., 2016; Weadman et al., 2021). Teacher educators often lack the deep level of complex literacy knowledge required for effective literacy practice (Binks-Cantrell et al., 2012; Joshi et al., 2009; Washburn & Mulcahy, 2014).

There is a strong desire from classroom teachers for evidence-based content and pedagogical knowledge that they feel they are lacking and need (Snow, 2020; Snow et al., 2024). In Scotland, the Measuring Quality in Initial Teacher Education report showed that graduate primary teachers were the least confident in their teaching of the languages curriculum (of which literacy is one of five sub-groups), giving it a rating of 2.8 out of 5 between 2018 and 2022 (Kennedy et al., 2023). Because trainee teachers are exposed to a range of literacy pedagogies, and a curriculum that does not offer clear direction on what literacy knowledge needs to be taught in what sequence in order to accrue reading skill, teacher confidence is low (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021).

This study involved the development, implementation, and evaluation of a Reading Elective course in the latter stages of the nine-month PGDE (Postgraduate Diploma in Education) for primary school teachers. The language of the study was English. It was a small-scale attempt to shift trainee teachers towards the body of empirical evidence at the beginning of their careers. The aim was to build their core literacy knowledge in intense sessions and set them on the right path for future professional development (Binks-Cantrell et al., 2012, 2022). The study assessed and utilized their current knowledge to implement training to maximize learning relevance and outcomes (Reynolds et al., 2022).

The three national enquiries that took place in the UK, US, and Australia clearly demonstrated that the best outcomes for all require the explicit, systematic teaching of phonics skills developing phonemic proficiency, along with vocabulary, fluency, comprehension, and background knowledge (National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy, 2005; National Reading Panel, 2000; Rose, 2006). The most recent research adds the importance of oral language, as both an overlapping but separate component, and quality morphology instruction (Goldfeld et al., 2022; James et al., 2021).

Teacher knowledge of language and literacy development positively impacts student outcomes in reading (Joshi et al., 2009; Moats & Foorman, 2003; Pittman et al., 2020). Knowledge is a prerequisite for quality instruction (Arrow et al., 2019; Piasta et al., 2009; Porter et al., 2023). Research has consistently evidenced that teachers lack the necessary knowledge after ITE to teach all children to read (Solari et al., 2020; Washburn et al., 2010). Teachers also overestimate their knowledge (Cunningham et al., 2004; Kehoe & McGinty, 2024). This is important given the difference between teachers’ perceived confidence in literacy instruction rather than their actual knowledge to teach literacy (Binks-Cantrell et al., 20224; Meeks et al., 2016).

Worldwide rates of reading failure are typically around 30% (Hempenstall, 2013; Moats, 1999). Young people’s engagement with reading for pleasure is at its lowest level ever (Topping, 2024). The attainment gap in literacy refers to the higher number of struggling readers who come from areas of deprivation in Scotland. Over a billion pounds has been allocated, unsuccessfully, to closing the attainment gap, by the Scottish Government, since the initiation of the Scottish Attainment Challenge (Scottish Government, 2023). The impact of COVID-19 has further exacerbated the literacy divide with pupils in Scotland losing, on average, 64 days of learning, with this trend mirrored across the UK, Ireland, and the US (Buckingham, 2024; Peters et al., 2024).

At-risk readers and those who have the least proficiency in reading show the lowest reading progress and attainment (Kuhfeld et al., 2023; Peters et al., 2024). Currently, 36.7% of Scottish pupils are identified as having an additional support need (ASN), with this number above 1 in 2 in some schools in the most deprived areas (Scottish Government, 2023). This figure has doubled in the past decade, continues to increase, and is mirrored across the world (Boyle & Anderson, 2020; Scottish Government, 2023; Véronique et al., 2022).

Current literacy provision is not meeting the needs of many learners and particularly those who need high-quality reading instruction, such as children with impaired language development or executive functioning (Fletcher et al., 2019; Snowling & Hulme, 2024). A recent meta-analysis of students with disabilities, compared with their typically developing peers, showed a gap of over three years in reading achievement (Gilmour et al., 2019).

Research evidence has consistently demonstrated that dyslexia and difficulties in phonological processing can be identified at as young as nursery and early intervention and evidence-based reading instruction can not only remediate but also prevent reading difficulties (Fletcher et al., 2019; Ozernov-Palchik & Gaab, 2016). The gap between reading research and practice and the lack of transfer of complex knowledge to teaching practitioners impacts the teaching of reading to struggling readers and remediating reading difficulties (Moats, 2020; Snowling & Hulme, 2024).

Dyslexic and other “at-risk” readers including children with any vulnerability in language or executive functioning, do not require different reading instruction to other learners: they require an increased dosage, frequency, and intensity of explicit systematic instruction of evidence-based practices and targeted support according to their specific skill lag (Barquero et al., 2014; Burns et al., 2023; Duke & Cartwright, 2021). Recent research has called for scaling up both screening and intervention with widely available evidence-based practices (Snow et al., 2024; Snowling & Hulme, 2024).

Because the clear empirical evidence on how to effectively teach reading tends not to be transferred successfully to ITE, there needs to be an increased focus on literacy in ITE (Buckingham, 2024; Duke & Cartwright, 2021; Solari et al., 2020). As highlighted by Moats (2020): “The tragedy here is that most reading failure is unnecessary”. Policy changes in England, Ireland, Australia, and across 30 US states now mandate that children in schools must be taught to read using research informed practice. For teachers to successfully teach reading they need to have both content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge (Hall et al., 2023; Moats, 2020).

Cognitive load theory has been described as the most important theory that teachers need to understand and apply—this theory equally applies to student learners of new and complex knowledge, as well as pupils in a classroom (Sweller, 2022; Wiliam, 2011). Cognitive load theory demonstrates that limitations on the working memory impact both processing and long-term remembering, and the ability to connect to networks of knowledge and create new knowledge and learning (Clark et al., 2012; Lovell & Sherrington, 2020). Because student teachers are novice learners of complex literacy concepts and models, and because they need to acquire both content and pedagogical knowledge, a practice focus with maximum opportunities for response is key to trainee teachers’ development of knowledge and skills (Archer & Hughes, 2011; Kirschner et al., 2022). This study adds findings on the impact of a novel training activity in a teacher training program for increasing knowledge of the effective elements of reading instruction and preparedness of trainee teachers for practice. It highlights a new method of empowering trainee teachers for effective future professional development in reading instruction.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of an elective course for primary PGDE trainee teachers delivered towards the end of their university on-campus teaching time and immediately before their entry to their final teaching practice block in a primary school. This study documents the development, delivery, and evaluation of a reading elective course to identify which areas students increased their knowledge through this additional teaching and to evaluate the value that trainee teachers gave it. Three research questions guided the study:

- Did the elective improve knowledge and understanding of literacy concepts?

- What areas did trainee teachers increase their knowledge in?

- What did trainee teachers value most about the elective?

2. Methodology

2.1. Description of Elective/Intervention

The Action Research Design intervention was designed as 3 × 2 h workshops, lecturer-led inputs (Reading 1, Reading 2, Reading 3), and 3 × 1 h independent learning student-led time: 9 h total. The objective was to increase knowledge and understanding of the core literacy content areas: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension, spelling, and assessment.

A key success criterion was the ability to define these key reading concepts. For this part, students were able to consistently check and verify each other’s definitions every time the concept was mentioned by the tutor or a student and as part of a low-stakes quizzing process. This progressive learning ensured deeper knowledge development for student teachers and was a springboard for application in their practice (Hall et al., 2023; Paas et al., 2003; Paas & van Merriënboer, 2020).

The reading intervention utilized goals, continuous formative assessment, and retrieval practice:

- (A)

- Shared clear learning intentions overall and shared clear learning intentions for each of the three inputs, so that student teachers understood the big picture, where they were going, and the steps throughout

- (B)

- Low-stakes pair quizzing throughout each session to increase learning and elicit evidence of learning, providing feedback from quizzes to move the learners forward

- (C)

- Activating students as owners of their own learning through the individual roles within the group task to move them forward in their learning and for the assessment of arriving there

- (D)

- Activating student teachers as learning resources for one another through a final collaborative paired presentation task.

The use of low-stakes quizzing as a form of retrieval practice not only drew attention to and reinforced the learning of key concepts but also formatively assessed student-teacher progression. This approach aimed to increase the acquisition of both content and pedagogical knowledge, thereby enhancing both confidence and competence in teaching reading (Wiliam, 2011; Lovell & Sherrington, 2020). The students worked in pairs and switched pairs frequently throughout the sessions, and then they were paired for the final task based on their selection of one of the five key reading conceptual areas.

The final input utilized the two key strategies of: (1) Activating students as learning resources for one another; and (2) Activating students as owners of their learning (Wiliam, 2011). This occurred as a pair worked together to provide a PowerPoint presentation on one of the key reading areas for the final two-hour session. Each pair focused on one area where they would acquire the deepest knowledge and showed how this would relate to all the other areas (Lovell & Sherrington, 2020).

For their overall learning, and specifically for the final group task, the students accessed the evidence-based self-paced module (https://www.readingrockets.org/reading-101/reading-101-learning-modules/course-modules, accessed on 2 January 2025). Each small group of two or three students was assigned one key area from: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension, spelling, and Assessment. This enabled each group to delve deeply into one area of knowledge while advancing their learning in the other areas through the presentations, tasks, and signposting to key reading and multimedia resources shared by their peers.

Each group could cover one area in depth in the 3 × 1 h assigned for individual learning. Each area included a pre-test, core reading, additional reading, in-practice, assignments, and a post test. In the short time frame, it was important to ensure some breadth and, most importantly, the theoretical evidence-based underpinnings and resources (Buckingham & Meeks, 2019; Snow et al., 2024).

The students assigned themselves specific roles while they worked on their chosen area. Afterward, they collaborated to complete a post test related to the subject. Finally, they created a presentation for their peers, highlighting the key learning points and providing references to important readings, multimedia resources, practice examples, and evidence-based materials that could be used by them when they went out on practice.

This was the first time that this elective had run and the intervention of the 3 × 2 h lecture tutor workshops with 3 × 1 h independent learning time was developed based on ongoing research (Buckingham, 2024; Snow et al., 2024).

2.2. Participants

The elective was capped at n = 16. After full ethical approval was granted by the university, the 16 trainee primary teachers were emailed with information about the research and invited to participate. All of them agreed to participate. There were 12 female and 4 male participants, all were native English speakers. They had all previously completed at least an ordinary undergraduate degree or equivalent. They had also all already completed two 6-week blocks of school placement training within a school and had one final 6-week block to complete after this elective training.

2.3. Measures

An open-ended questionnaire approach was utilized and administered to the student teachers before the first elective and again after the elective was completed. The questionnaire had three questions to give the participants maximum opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the key reading concepts, evidence-based reading instruction, at-risk readers, and impact of teacher instruction on reading (Hall et al., 2023; Moats, 1999, 2020). The data collection procedure involved the questionnaire being emailed to the participants prior to the first elective unit (Reading 1) and then again after the final elective unit (Reading 3). The questionnaire had three open questions:

- Define and describe high-quality reading instruction across all stages of primary school?

- Describe those children who might be at risk of reading difficulties and why this would be?

- How can we, as teachers, minimize reading difficulties and support struggling readers?

The questions were open-ended so that relatively elaborate responses to each were expected and there were open text boxes for each question. The students were also asked to define the five core components of reading instruction (phonemic awareness, phonics instruction, fluency instruction, vocabulary instruction, and comprehension instruction) along with reading assessment that would be/were covered in the elective course, and rate their knowledge and of them.

Participation was voluntary, which minimized ethical concerns, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The participants followed a web link to the questionnaire and the data was collected via Microsoft forms where the participants typed their responses. The pre-test data was collected over 2 weeks prior to the first elective and the post-test data was collected 2 weeks after the last elective. All participants completed the first questionnaire without any reminders and there was a reminder email send to two participants after the final elective. All participants completed all the questions. The responses from before and after the elective were compared. Their ratings from before and after the elective were compared.

2.4. Data Analysis

This action research utilized a content analysis to organize and categorize the data into a clear thematic framework (Patton, 2002; Snow et al., 2024). The main process was an interpretational qualitative analysis approach—fundamentally, an inductive analysis with no predetermined categories for the data (Scanlan et al., 1989, 1991; Snow et al., 2024).

The responses to each of the three questions, for both pre- and post-test, were organized into data sets and systematically analyzed, resulting in a clear thematic framework (Patton, 2002). Patterns were categorized and classified, by seeking refinement of the data through the similarities of the properties within that specific category and the differences to those categories without (Patton, 2002). Comparing the themes from the pre-elective questionnaire data with the post-elective questionnaire enabled the research questions to be answered and an examination of the knowledge and concepts that the trainee teachers were learning/not learning.

Each of the questionnaires was read and re-read in order that the researcher was familiar with the perceptions of the experiences of each participant, but also had a holistic sense of the complete data set (Scanlan et al., 1989). Meaning units—segments of texts—were highlighted on every single questionnaire (Scanlan et al., 1991). The basic unit of analysis was defined as the text unit comprised of a quote made up of a phrase, sentence, or paragraph, which represented one single perception of a reading instruction (Scanlan et al., 1989). Alongside each of these text units, a general description was typed that described its topic: a tag. The tag was an interpretative description of the information given in the data and involved summarizing or defining the data. Natural divisions were immediately created because some tags were the same, e.g., “those who are not read to at home” and “parents not reading to their kids” were both tagged as “not read to at home”.

Some were similar and then condensed as relationships and patterns were identified in the second stage of the data analysis (Patton, 2002): data interpretation. The process of analysis looked not only for relationships and patterns but also for contraindications and ambiguities (Patton, 2002). The entire set of tagged meaning units for each question pre- and post-test was printed out, each tag was separately cut out and each question data set was interpreted, analyzed, and categorized separately, resulting in a table of themes for each question pre- and post- elective. The researcher then analyzed the similarities and differences to the tags that were already established, before fixing each to a theme or sub-theme (Côté et al., 1993). Some tags were identical to their comment, e.g., “home environment” was tagged with “home environment” and became part of the theme: Literacy-Poor Environment, along with other comments such as “Children who were not encouraged to use language in their early childhood” and “Children from poor socio-economic backgrounds who may not have access to books”.

3. Results

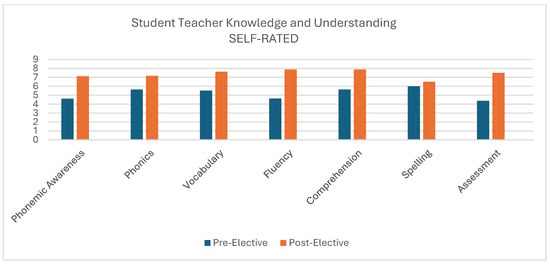

Self-rated student teacher knowledge and understanding increased. The largest increases were for reading fluency and reading assessment. The qualitative data demonstrated that reading fluency and reading assessment were two areas that trainee teachers did not identify as part of quality reading instruction prior to the elective training. Previously, self-rating and teacher confidence measures were often used as a justification, but this study did not rate generalized “teaching literacy” as other studies/reports have, but focused on key components of reading, such as phonemic awareness and vocabulary.

As underlined by Moats (2020), “The demands of competent reading instruction, and the training experiences necessary to learn it, have been seriously underestimated”. However, the participants themselves were able to articulate that they had overestimated their knowledge at the start and now they were aware of how much more complex each component was. Although they had increased their knowledge, they were aware of how much more they still had to learn. The following figure (Figure 1) illustrates the increase in self-rated knowledge for each of the key component areas of reading instruction:

Figure 1.

Mean increase in the student teacher self-rating score of knowledge and understanding of key components of reading instruction.

3.1. Thematic Analysis

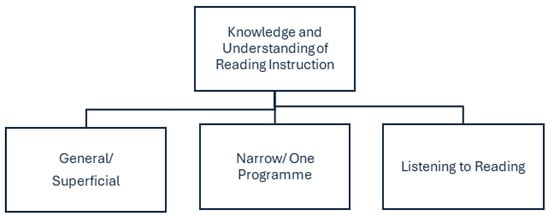

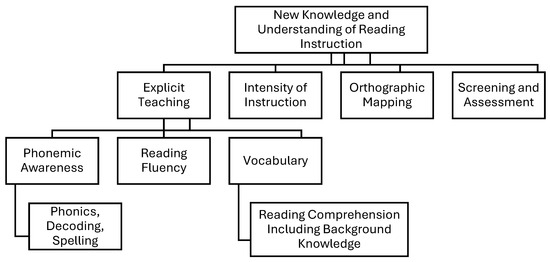

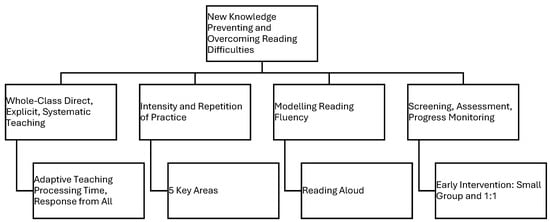

3.1.1. Knowledge and Understanding of Reading Instruction

The resulting themes from the systematic analysis of question 1. Define and describe high-quality reading instruction across all stages of primary school? are presented in Figure 2 (prior to the training intervention) and Figure 3 (after the training intervention) below. Prior to the elective, trainee teachers’ understanding of reading instruction was very superficial and generalized. After the elective, the trainee teachers were able to identify and demonstrate an understanding of the core components of effective evidence-based reading instruction as displayed in Figure 2 and Figure 3:

Figure 2.

Student teacher understanding of evidence-based reading instruction prior to the elective.

Figure 3.

Student teacher understanding of evidence-based reading instruction after the elective.

Prior to the elective, the understanding of evidence-based reading instruction was superficial, as demonstrated by the general and generic comments such as “Children can actively access literacy through different mediums and have support where necessary to help build their understanding and confidence in their reading” and “The instruction is accessible, equitable, and interactive to really engage the learners across all different types of text”. The student teachers gave very basic comments, such as “I think children not only need to be reading the words but also understanding what they are reading”.

At the outset, trainee teachers reported listening to reading as a key reading instruction practice: “Find opportunities to hear the children read multiple times a week”. This short intensive elective was able to change some of the misconceptions about how children learn to read and trainee teachers were able to change their focus from listening to reading to “increased explicit teaching of reading skills”. After the elective, they saw that their responsibility was to increase “skills through repetition and practice”, along with “progress monitoring” and “assessment”.

There was a new understanding of phonics as only one key part, and they now had access to evidence-based resources and phonics knowledge. They had also learned that phonemic awareness underpins reading development, but that vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension not only need to be taught but taught directly.

Prior to the elective, trainee teachers did not specifically describe any of the five instructional areas, apart from phonics (highlighted by the three national reading enquiries), but after the elective, they were able to identify each as an individual but also an overlapping component. The trainee teachers had a new understanding of reading fluency as a skill to be taught and an understanding of the strength of the evidence base around specific fluency instruction and practice.

The trainee teachers were now able to understand that reading is not a natural process and has to be explicitly taught, so that children, particularly those at risk, are able to develop the ability to orthographically map. Another of the areas that the trainee teachers gained new knowledge about and increased understanding of was reliable assessments for reading to enable teachers to effectively teach and develop literacy skills for all.

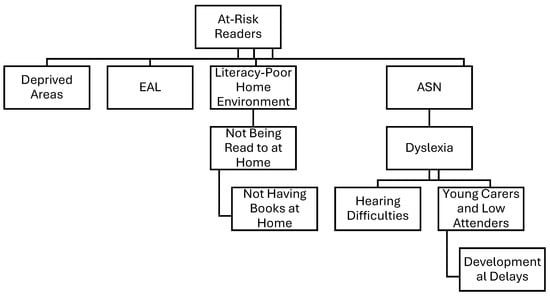

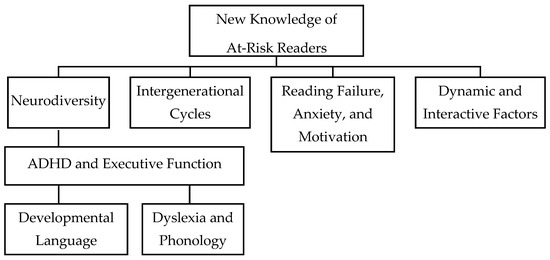

3.1.2. Knowledge and Understanding of At-Risk Readers

The themes resulting from the systematic analysis of question 2. Describe those children who might be at risk of reading difficulties and why this would be? are presented in Figure 4 (prior to the training intervention) and Figure 5 (after the training intervention). Prior to the elective, trainee teachers had some understanding of the societal factors that contribute to young people being at risk of reading difficulties, including deprivation and home environment. They also had a basic understanding of some of the additional support needs that would contribute to a child being at risk of reading difficulties. However, after the elective, their understanding of additional support needs and reading difficulties was broadened and deepened.

Figure 4.

Understanding of at-risk readers pre-elective.

Figure 5.

Understanding of at-risk readers after the elective.

Prior to the elective, student teachers had a strong understanding of the influence of home environments on children’s literacy development and mainly saw at-risk readers as those “who come from homes with low literacy skills”, “those who are not read to at home”, and “children from poor socio-economic backgrounds who may not have access to books as easily”. Whilst home environment does influence children’s language and literacy skills, and particularly their early reading skills, it is important for trainee teachers to focus on ensuring best classroom practice in reading and literacy instruction, because quality reading instruction implemented in schools can address language needs and gaps and develop the skills that children need to become efficient readers.

Prior to the elective, the trainee teachers were able to identify some additional support needs (ASNs) that would cause a child to be at risk of reading failure, but they had a generalized view of ASNs without being able to identify specifics and overlaps in the support and/or instruction needed. After the elective, they had a much deeper and broader understanding of different ASNs in reading. Similarly to teachers’ misconceptions of learning to read, teachers had misconceptions about dyslexia that impacted on their ability to provide quality classroom instruction. By the end of the elective course, the trainee teachers had developed an understanding of dyslexia with a core phonological difficulty and had developed an understanding of their responsibility to address this through quality instruction by developing phonemic proficiency.

There was a new understanding of both language vulnerabilities and executive function vulnerabilities and the discrete differences and potential overlap between these, along with attention-based difficulties in reading: “Executive function issues that prevent learning to read—such as metacognition issues, sustaining attention, reduced working memory, and emotional control”; and “Children who suffer from difficulties impact reading skills such as dyslexia and DLD because these impact accuracy, fluency, and understanding, amongst other elements”.

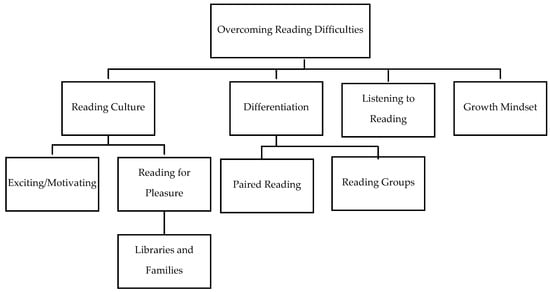

3.1.3. Knowledge and Understanding of Overcoming Reading Difficulties

The resulting themes from the systematic analysis of question 3. How can we, as teachers, minimize reading difficulties and support struggling readers? are presented in Figure 6 (prior to the training intervention) and Figure 7 (after the training intervention) below. Prior to the reading elective, the trainee teachers’ understanding of overcoming reading difficulties centered around reading for pleasure and generating a love of books, along with encouraging students who had previously failed in reading to keep working harder. After the elective, the trainee teachers were able to understand the five key components of quality reading instruction needed to instruct at-risk readers, along with a much clearer understanding of assessment as integral to this, along with screening, progress monitoring, and intervention as needed.

Figure 6.

Knowledge of instruction to overcome difficulties prior to the elective.

Figure 7.

Knowledge of the impact of teacher practice to minimize and support struggling readers after the elective.

Prior to the elective, student teacher understanding of supporting struggling readers was also very generalized, with comments such as “Look at differentiation and strategies that can be adapted to help the children realize their potential”. There was a clear emphasis on motivating children through reading for pleasure and rich reading environments: “Create a reading culture”; “Engaging material”; and “Find ways to get children excited about books and reading so that they are motivated and engaged despite any potential challenges”.

After the elective, early intervention was emphasized and student teachers had a new, clearer understanding of the importance of this: “Solid understanding of reading difficulties and early intervention is also crucial—teachers cannot minimize the effects of reading difficulties if they do not know what they are or how to do so, or that a particular child even has one in the first place”.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of a specifically designed intervention on trainee teachers’ knowledge and understanding of literacy instruction. The research is clear that reading skills need to be taught explicitly and systematically and at-risk readers need a higher dose, intensity, and frequency of instruction than typical learners (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2015; Kearns et al., 2022; Torgesen, 2002). The findings from this study support the literature demonstrating how teachers lack the required complex knowledge to teach all children to read after their initial training (Solari et al., 2020; Washburn et al., 2010). The elective was successful in focusing trainee teachers on the best practice of explicit instruction and their instructive role to increase responses and practices which, along with immediate corrective feedback, can ensure that all children are given the opportunity for success (Archer & Hughes, 2011; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2015).

Prior to the training elective, one program was highlighted four times by the trainee teachers as an example of best practice in quality reading instruction—Ruth Miskin’s “Read Write Inc”—which is a commercially produced systematic phonics scheme that is widely used where many of the students had spent their placement practices. A two-year effectiveness trial by the Education Endowment Foundation found the program to have only low to moderate effectiveness (Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), 2022). In the intervention, children made, on average, only one additional month of progress in reading and phonics skills compared with the control group.

Relying on commercially produced phonics and other reading programs as a primary training source for teachers is a haphazard and unsound way to equip them with the complex knowledge and skills they need. Systematic phonics instruction becomes quality instruction when teachers are trained and develop a deep knowledge of learning to read (Castles et al., 2018; Snow, 2020, 2021). The trainee teachers developed an understanding of the evidence base around reading fluency and other bridging processes and how to teach these to facilitate the practice required to ensure the best outcomes for all children (Duke & Cartwright, 2021; Padeliadu & Giazitzidou, 2018). The necessity of explicit instruction in phonics skills in order to facilitate orthographic mapping is one part of a deeper and wider understanding that reading teachers need (Ehri, 2012; Levesque et al., 2021; Spear-Swerling, 2019). This study supports the recent research on novel ways of increasing trainee and in-service teachers’ knowledge of reading instruction so that they have core complex knowledge, which is the basis of effective practice (Snow et al., 2024).

A recent report has demonstrated that almost half of teachers of children aged 8–13 years rely on classroom experience as a main source of knowledge for teaching reading and three-quarters of teachers reported needing access to more training and resources (Shapiro et al., 2024). This report also highlighted that 40% of teachers teaching children aged 9–13 years have misconceptions about how children learn to read. Researchers estimate that 95% of students can be taught to read, the exception being those with the most severe learning disabilities (Goldberg & Goldenberg, 2022; Moats, 2020). Focusing on quality instruction gives trainee teachers control over where and how they could make an impact in improving literacy outcomes and change the commonly held misconceptions about learning to read that exist in practice (Shapiro et al., 2024; Snow et al., 2024).

Research across the world has shown that children from disadvantaged backgrounds learn to read well when they receive quality instruction from knowledgeable teachers and appropriately targeted interventions (Burns et al., 2023; Foorman et al., 2006; Vaughn et al., 2010). Similarly, many children from literacy-rich and supportive environments can struggle with learning to read—especially if they are not given quality instruction and they are at risk, such as with a language impairment (Mathes et al., 2005; Riccomini et al., 2017).

Children with language impairment often went undiagnosed, as did children with other moderate language difficulties, and were at risk of reading comprehension difficulties and subsequent academic failure and emotional distress (Adlof & Hogan, 2019; Cortelia & Horowitz, 2014). Teachers increasingly teach a significant number of young people with multiple and often co-occurring additional learning needs and the majority of these will have difficulties with reading and often experience multiple challenges. This study supports the research base highlighting that teachers hold misconceptions about dyslexia and reading instruction (Castles et al., 2018; Peltier et al., 2022). This study supports the increasing literature base on the urgent necessity to improve teacher training in reading instruction and equip teachers with the knowledge to teach all children to read (Snow et al., 2024; Kehoe & McGinty, 2024). The elective increased awareness and understanding of the difficulties of the child, as well as the impact of the teacher, which empowered the trainee teachers to go forward and provide young people with evidence-based instruction to make a difference in reading outcomes (Clark et al., 2012; Cortelia & Horowitz, 2014; Piasta et al., 2009).

Teacher voice is significantly underrepresented in the research literature and these trainee teachers highlighted that they found the elective extremely valuable and that it increased their knowledge to improve their practice: “I think this is key information that should be at the forefront of the PGDE primary course”; and “It has helped me make more sense of what I have been teaching whilst on placements and has provided me with more knowledge to take forward. This would be really beneficial being included into the full program for everyone”. As highlighted earlier, teaching reading is complex and teachers overestimate their knowledge (Cunningham et al., 2004; Kehoe & McGinty, 2024).

The elective provided one means of beginning to close the teacher knowledge gap and ensure that trainee and beginning teachers understood how much more they had to learn in practice, because “It showed the stages and complexity of the learning to read process, which I was not aware of”. The trainee teachers felt empowered by their access to evidence-based resources and training that would allow them to develop evidence-based practice further in-service: “The reading 101 website is excellent and engaging, it will be my go-to. I now view teaching children to read … as the most important role”.

The elective course was successful in improving the knowledge and understanding of complex literacy concepts in this small group of trainee teachers in a short time and setting them on the path for fruitful future professional development: to continue to learn and successfully apply their knowledge to practice for the best outcomes for the young people that they will teach.

ITE should increase the focus on preparing student teachers to acquire complex evidence-based knowledge about how to teach reading. ITE staff should be given development time for this type of training for teachers.

5. Conclusions

This action research demonstrated that student trainee primary/elementary teachers had some understanding of reading instruction, but there were significant gaps at the end of their university teaching, and they also held misconceptions. The elective intervention was successful as trainee teachers increased their knowledge of each of the core components of effective reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension, with the greatest gains in the understanding of reading fluency and reading assessment (Hall et al., 2023; Pittman et al., 2020). Analysis of the qualitative data demonstrated that neither reading fluency or reading assessment were identified when the student teachers were asked about reading instruction prior to the elective, but they identified were after, and the student teachers were able to demonstrate the beginning of understanding and access to evidence-based resources for future development.

Trainee teachers increased their personal knowledge of reading instruction while simultaneously increasing their understanding of the complex breadth and depth of knowledge still to be learned by them for successful practice. Rather than overestimating their knowledge, they now had a realistic view of how much they needed to focus on reading in practice and had research-based resources to guide them in their journey of professional development (Stark et al., 2016).

There were limitations in that this was a small-scale action research study. The sample was small and was composed of trainee teachers selecting this area for extra training, so we do not know if this intervention would have been as successful with unselected student teachers. The instruments were deliberately brief and open-ended, enabling the participants to respond in a relatively unstructured way, but a more structured approach might have asked more penetrating questions. Clearly, the generalization from this study is somewhat questionable, and of course the question of the effects at long-term follow-up have not been explored.

Future research should consider the most impactful ways of scaling up this intervention. The qualitative data set generated from the responses to open questions would be enhanced in future studies in follow-up focus groups or interviews to gain a deeper understanding of the knowledge developed and also consider the implications and impact that the training had on the trainee teachers’ future practice and professional development in reading instruction. The trainee teachers selected this elective and therefore were more invested in developing this area, so future research should consider the impact of this training with a sample from the general population of teachers. Future research should continue to focus on how best to improve trainee and in-service teachers’ knowledge of complex content and pedagogical knowledge, and access to evidence-based research.

Author Contributions

J.M. collected the data, and J.M. and K.J.T. worked on the written article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Dundee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the trainee teachers for their participation in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to resolve spelling and grammatical errors. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Adlof, S. M., & Hogan, T. P. (2019). If we don’t look, we won’t see: Measuring language development to inform literacy instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(2), 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, A. W., Braid, C., & Chapman, J. W. (2019). Explicit linguistic knowledge is necessary, but not sufficient, for the provision of explicit early literacy instruction. Annals of Dyslexia, 69(1), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barquero, L. A., Davis, N., & Cutting, L. E. (2014). Neuroimaging of Reading Intervention: A Systematic Review and Activation Likelihood Estimate Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(1), e83668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binks-Cantrell, E., Hudson, A., Washburn, E., Contesse, V., Peltier, T., & Lane, H. (2022). Teaching the teachers: The role of teacher education and preparation in reading science. The Reading League Journal, 3(3), 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Binks-Cantrell, E., Washburn, E. K., Joshi, R. M., & Hougen, M. (2012). Peter effect in the preparation of reading teachers. Scientific Studies of Reading, 16(6), 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, C., & Anderson, J. (2020). The justification for inclusive education in Australia. Prospects, 49(3–4), 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, J. (2024). An investigation of literacy instruction and policy in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Churchill Fellowship Report. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, J., & Meeks, L. (2019). Shortchanged: Preparation to teach reading in initial teacher education. Five from five. Available online: https://fivefromfive.com.au/publications/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Burns, M. K., Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2023). Evaluating components of the active view of reading as intervention targets: Implications for social justice. School Psychology, 38(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 5–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R. E., Kirschner, P. A., & Sweller, J. (2012). Putting students on the path to learning: The case for fully guided instruction. American Educator, 36(1), 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cortelia, C., & Horowitz, S. H. (2014). The state of learning disabilities: Facts, trends and emerging issues. National Center for Learning Disabilities; Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE); Institute of Education Sciences, United States Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Côté, J., Salmela, J. H., Baria, A., & Russell, S. J. (1993). Organizing and interpreting unstructured qualitative data. The Sport Psychologist, 7(2), 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A. E., Perry, K. E., Stanovich, K. E., & Stanovich, P. J. (2004). Disciplinary knowledge of K-3 teachers and their knowledge calibration in the domain of early literacy. Annals of Dyslexia, 54(1), 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S25–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Endowment Foundation (EEF). (2022). Research into read write Inc. phonics. A report on lessons learned. EEF. [Google Scholar]

- Ehri, L. C. (2012). Word reading by sight and by analogy in beginning readers. In Reading and spelling (pp. 87–111). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J. M., Lyon, G. R., Fuchs, L. S., & Barnes, M. (2019). A Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foorman, B. R., Schatschneider, C., Eakin, M. N., Fletcher, J. M., Moats, L. C., & Francis, D. J. (2006). The impact of instructional practices in Grades 1 and 2 on reading and spelling achievement in high poverty schools. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 31(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2015). Rethinking service delivery for students with significant learning problems. Remedial and Special Education, 36(2), 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, A. F., Fuchs, D., & Wehby, J. H. (2019). Are students with disabilities accessing the curriculum? A meta-analysis of the reading achievement gap between students with and without disabilities. Exceptional Children, 85(3), 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M., & Goldenberg, C. (2022). Lessons learned? Reading wars, reading first, and a way forward. The Reading Teacher, 75(5), 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfeld, S., Snow, P., Eadie, P., Munro, J., Gold, L., Le, H. N. D., Orsini, F., Shingles, B., Connell, J., Watts, A., & Barnett, T. (2022). Classroom promotion of oral language: Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a whole-of-classroom intervention to improve children’s reading achievement. AERA Open, 8, 23328584221131530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C., Solari, E. J., Hayes, L., Dahl-Leonard, K., DeCoster, J., Kehoe, K. F., Conner, C. L., Henry, A. R., Demchak, A., Richmond, C. L., & Vargas, I. (2023). Validation of an instrument for assessing elementary-grade educators’ knowledge to teach reading. Reading Writing, 37(8), 1955–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempenstall, K. (2013). What is the place for national assessment in the prevention and resolution of reading difficulties? Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 18(2), 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, E., Currie, N. K., Tong, S. X., & Cain, K. (2021). The relations between morphological awareness and reading comprehension in beginner readers to young adolescents. Journal of Research in Reading, 44(1), 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R. M., Binks, E., Hougen, M., Dahlgren, M. E., Ocker-Dean, E., & Smith, D. L. (2009). Why elementary teachers might be inadequately prepared to teach reading. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(5), 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearns, D. M., Walker, M. A., Borges, J. C., & Duffy, M. E. (2022). Can reading practitioners and researchers improve intensive reading support systems in a large urban school system? Journal of Research in Reading, 45(3), 488–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, K. F., & McGinty, A. S. (2024). Exploring teachers’ reading knowledge, beliefs and instructional practice. Journal of Research in Reading, 47(1), 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A., Carver, M., & Adams, P. (2023). Measuring quality in initial teacher education: Final report. Scottish Council of Deans of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, P., Hendrick, C., & Heal, J. (2022). How teaching happens: Seminal works in teaching and teacher effectiveness and what they mean in practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfeld, M., Lewis, K., & Peltier, T. (2023). Reading achievement declines during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from 5 million U.S. students in grades 3–8. Reading and Writing, 36(2), 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, K. C., Breadmore, H. L., & Deacon, S. H. (2021). How morphology impacts reading and spelling: Advancing the role of morphology in models of literacy development. Journal of Research in Reading, 44(1), 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, O., & Sherrington, T. (2020). Sweller’s cognitive load theory in action. John Catt. [Google Scholar]

- Mathes, P. G., Denton, C. A., Fletcher, J. M., Anthony, J. L., Francis, D. J., & Schatschneider, C. (2005). The effects of theoretically different instruction and student characteristics on the skills of struggling readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(2), 148–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccombes-Tolis, J., & Spear-Swerling, L. (2011). The preparation of preservice elementary educators in understanding and applying the terms, concepts, and practices associated with response to intervention in early reading contexts. Journal of School Leadership, 21(3), 360–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeks, L., Stephenson, J., Kemp, C., & Madelaine, A. (2016). How well prepared are pre-service teachers to teach early reading? A systematic review of the literature. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 21(2), 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moats, L. C. (1999). Teaching reading is rocket science: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. American Federation of Teachers. [Google Scholar]

- Moats, L. C. (2020). Speech to print: Language essentials for teachers (3rd ed.). Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Moats, L. C., & Foorman, B. R. (2003). Measuring teachers’ content knowledge of language and reading. Annals of Dyslexia, 53(1), 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy. (2005). Teaching reading: Report and recommendations. Department of Education, Science and Training. Available online: https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=tll_misc (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- National Reading Panel. (2000). The national reading panel report. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Available online: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/documents/report.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). Scotland’s curriculum for excellence: Into the future. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozernov-Palchik, O., & Gaab, N. (2016). Tackling the ‘dyslexia paradox’: Reading brain and behavior for early markers of developmental dyslexia. WIREs Cognitive Science, 7(2), 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2003). Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2020). Cognitive-load theory: Methods to manage working memory load in the learning of complex tasks. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(4), 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padeliadu, S., & Giazitzidou, S. (2018). A synthesis of research on reading fluency develompent: Study of eight meta-analyses. European Journal of Special Education Research, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and education methods (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Peltier, T. K., Washburn, E. K., Heddy, B. C., & Binks-Cantrell, E. (2022). What do teachers know about dyslexia? It’s complicated! Reading and Writing, 35(9), 2077–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S. J., Langi, M., Kuhfeld, M., & Lewis, K. (2024). Unequal learning loss: How the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the academic growth of learners at the tails of the achievement distribution (pp. 23–787). EdWorkingPaper. Annenberg Institute at Brown University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petscher, Y., Cabell, S. Q., Catts, H. W., Compton, D. L., Foorman, B. R., Hart, S. A., Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., Schatschneider, C., Steacy, L. M., Terry, N. P., & Wagner, R. K. (2020). How the science of reading informs 21st-century education. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(Suppl. S1), S267–S282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piasta, S. B., Connor, C. M., Fishman, B. J., & Morrison, F. J. (2009). Teachers’ knowledge of literacy concepts, classroom practices, and student reading growth. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(3), 224–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, R. T., Zhang, S., Binks-Cantrell, E., Hudson, A., & Joshi, R. M. (2020). Teachers’ knowledge about language constructs related to literacy skills and student achievement in low socio-economic status schools. Dyslexia, 26(2), 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S. B., Odegard, T. N., Farris, E. A., & Oslund, E. L. (2023). Effects of teacher knowledge of early reading on students’ gains in reading foundational skills and comprehension. Reading and Writing, 37(8), 2007–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B. L., Yu, M. H., & Li, M. (2022). Pre-service English teachers’ understanding about preparing to teach reading skills in secondary schools. Review of Education, 10(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccomini, P. J., Morano, S., & Hughes, C. A. (2017). Big ideas in special education: Specially designed instruction, high-leverage practices, explicit instruction, and intensive instruction. Teaching Exceptional Children, 50(1), 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J. (2006). Independent review of the teaching of early reading. Department for Education and Skills. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, T. K., Stein, G. L., & Ravizza, K. (1989). An in-depth study of former elite figure skaters: II. sources of enjoyment. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, T. K., Stein, G. L., & Ravizza, K. (1991). An in-depth study of former elite figure skaters: III. sources of stress. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(2), 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. (2023). Summary statistics for schools in Scotland 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/summary-statistics-for-schools-in-scotland-2023/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Seidenberg, M. S., Borkenhagen, M. C., & Kearns, D. M. (2020). Lost in translation? Challenges in connecting reading science and educational practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(Suppl. S1), S119–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A., Sutherland, R., & Kaufman, J. H. (2024). What’s missing from teachers’ Toolkits to support student reading in grades 3–8: Findings from the rand American teacher panel. Rand Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3358-1.html (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Snow, P. (2020). Balanced literacy or systematic reading instruction? Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, P., Serry, T., Charles, E., & Barbousas, J. (2024). Build it and they will come: Responses to the provision of online science of language and reading professional learning. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 29(2), 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, P. C. (2021). SOLAR: The science of language and reading. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 37(3), 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowling, M., & Hulme, C. (2024). Do we really need a new definition of dyslexia? A commentary. Annals of Dyslexia, 74(3), 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solari, E. J., Terry, N. P., Gaab, N., Hogan, T. P., Nelson, N. J., Pentimonti, J. M., Petscher, Y., & Sayko, S. (2020). Translational science: A road map for the science of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(Suppl. S1), S347–S360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear-Swerling, L. (2019). Structured literacy and typical literacy practices: Understanding differences to create instructional opportunities. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 51(3), 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, H. L., Snow, P. C., Eadie, P. A., & Goldfeld, S. R. (2016). Language and reading instruction in early years’ classrooms: The knowledge and self-rated ability of Australian teachers. Annals of Dyslexia, 66(1), 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (2022). The role of evolutionary psychology in our understanding of human cognition: Consequences for cognitive load theory and instructional procedures. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 2229–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topping, K. (2024). Is reading on the decline in schools? Teaching Times. [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen, J. K. (2002). Lessons learned from intervention research in reading: A way to go before we rest. Learning and Teaching Reading, 1(1), 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, S., Denton, C. A., & Fletcher, J. M. (2010). Why intensive interventions are necessary for students with severe reading difficulties. Psychology in the Schools, 47(5), 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véronique, I., Jijun, Z., Xiaolei, W., Sarah, H., Ke, W., Ashley, R., Christina, Y., Amy, B., Bullock, M. F., Rita, D., & Stephanie, P. (2022). Report on the condition of education 2022 (p. 144). NCES. National Center for Education Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Washburn, E. K., Joshi, R. M., & Cantrell, E. B. (2010). Are preservice teachers prepared to teach struggling readers? Annals of Dyslexia, 61(1), 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, E. K., & Mulcahy, C. A. (2014). Expanding preservice teachers’ knowledge of the english language: Recommendations for teacher educators. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 30(4), 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weadman, T., Serry, T., & Snow, P. C. (2021). Australian early childhood teachers’ training in language and literacy: A nation-wide review of pre-service course content. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 46(2), 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiliam, D. (2011). What is assessment for learning? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).