Abstract

Education systems are moving to a more evidence-informed paradigm to improve outcomes for learners. To help this journey to evidence, robust qualitative and quantitative research can help decisionmakers identify more promising approaches that provide value for money. In the context of the utilisation of scarce resources, an important source of evidence commonly used in health and social care research is an understanding of the economic impact of intervention choices. However, there are currently very few examples where these methodologies have been used to improve the evaluation of education interventions. In this paper we describe the novel use of an economic analysis of educational interventions (EAEI) approach to understand both the impact and the cost of activities in the evaluation of a formative assessment implementation project (FAIP) designed to improve teachers’ understanding and use of formative assessment strategies. In addition to utilising a mixed method quasi-experimental design to explore the impact on learner wellbeing, health utility and attainment, we describe the use of cost-consequence analysis (CCA) to help decisionmakers understand the outcomes in the context of the resource costs that are a crucial element of robust evaluations. We also discuss the challenges of evaluating large-scale, universal educational interventions, including consideration of the economic tools needed to improve the quality and robustness of these evaluations. Finally, we discuss the importance of triangulating economic findings alongside other quantitative and qualitative information to help decisionmakers identify more promising approaches based on a wider range of useful information. We conclude with recommendations for more routinely including economic costs in education research, including the need for further work to improve the utility of economic methods.

1. Introduction

Over recent years, education has moved towards a more evidence-informed paradigm, using research findings to help teachers and policymakers improve outcomes for learners (2020) [1,2,3,4]. This initiative has aligned with the need for education systems to provide value for money in relation to public spending and is underpinned by the concept of cost-effective decision making [2,5,6]. One way to help identify more value for money approaches is to routinely adopt economic evaluation methodologies within education research. In health economics, for example, there are a range of tools and approaches available to help decisionmakers assess the effectiveness and value for money of a course of action, with the aim of assigning scarce resources more judiciously [7,8]. These methodologies are, however, infrequently used in educational research, and the impact of interventions is rarely evaluated in the context of their cost to both the education setting in question and the wider system. The use of economic evaluations seeks to expand on educational research of ‘what works’ by adding the ‘how much’ to evaluate the impact of investing resources in different interventions and/or inputs [9]. In this study we introduce the concept of an economic analysis of educational interventions (EAEI) approach. This paper aims to explore how these methods can be used to help researchers incorporate EAEI in educational research to support decisionmakers to make better informed decisions that balance impact and resource costs.

The UK’s Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) supports the utilisation of evidence in education and produces a range of materials to help educators implement more promising approaches and programmes in schools. The EEF has also developed a guidance document to inform best practice on the collection and interpretation of cost data within the trials they fund [10]. Prior to this guidance, not all costs were routinely incorporated into programme evaluations, including the important omission of the consideration of staff costs to deliver interventions. In economics, this would be considered an opportunity cost, as the next best value-use of staff’s time must be considered when assessing value. In the United States, although the Center for Benefit–Cost Studies of Education has developed a suite of costing tools to help researchers and education administrators collect information on resource costs for evaluation purposes [11], more work needs to be done to improve the accessibility and understanding of how economic techniques can support policymakers to make better quality decisions [12]. More recently, Kraft [9] has highlighted the need to consider wider programme costs and issues of scalability into the process of interpreting impact findings to help policymakers make better informed decisions. However, although there are some examples of how researchers have used economic evaluations to improve the quality of findings—for example, Quinn, Van Mondfrans and Worthen [13] have evaluated two mathematical programmes and Hollands et al. [14] used economic evaluation to assess five different interventions that sought to increase the completion rates of secondary school—the use of economic evaluation techniques is still used infrequently within education research.

In the UK, researchers in other public services have developed more robust and formalised economic evaluation methodologies to support decisionmakers (for example, in the health sector, economic evaluations are now commonly used to support healthcare provision [15,16]). Given the lack of evidence for the use of robust economic tools in education research, this study aimed to explore how the use of health economic methods could improve the evaluation of a regional professional learning initiative in UK primary schools.

2. Formative Assessment in Policy and Practice

Over recent decades, there has been an uptake in formative assessment strategies to improve teaching quality [17,18,19,20]. Black and Wiliam’s influential publication Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards through Classroom Assessment [17] highlights the potential of formative assessment as an important set of strategies to help teachers and learners use information and evidence about learning to inform the next steps in instruction and improve outcomes. Over the next twenty years, the adoption of formative assessment strategies became a core feature of effective teaching approaches in many schools and has been supported by a wide range of research and professional learning materials for teachers [19,20,21,22,23,24]. In 2008, the UK Labour Government’s education policy emphasised the importance of including the principles and practice of formative assessment into initial teacher education provision [25], and these concepts, and related teaching strategies, continue to underpin much of the practical advice and guidance provided to teaching staff in schools [20,24,26]. Formative assessment was also included as an integral assessment strategy described “as the bridge between teaching and learning” in the Curriculum for Wales [27] (p. 76).

Effective formative assessment focuses on providing high-quality feedback to monitor learning and to provide ongoing feedback to learners. In contrast, summative assessment is commonly used to evaluate learning after a body of work is completed and/or at the end of a period of study. The continuous nature of formative assessment provides learners with real-time advice and feedback to move their learning forward. Feedback can be provided by teachers, peers, and/or the learner themself. As such, formative assessment can be considered a universal intervention delivered to all learners from primary schools through to higher education settings [28,29,30]. Formative assessment is an ongoing and integral aspect of instruction, seamlessly embedded within the learning process to continually inform and enhance teaching practices [31].

Although previous research has identified the positive impact of teachers’ use of formative assessment strategies on the outcomes achieved by struggling learners and learners from disadvantaged backgrounds [25,32], there is still debate on the trustworthiness and value of some of the outcomes reported in previous formative assessment research [21,33]. Additionally, Anders et al. [29] identified the difficulty of evaluating the implementation of large-scale formative assessment programmes administered by school staff with very limited implementation support from researchers and/or experts in the field.

According to James [25,34], effective formative assessment consists of three stages:

- Making observations: The teacher needs to explore what the learner does or does not know, and this is typically achieved by listening to learners’ responses, observing the learner on tasks, and/or assessing class or homework tasks.

- Interpretation: The teacher interprets the skill, knowledge, or attitudes of the learners.

- Judgement: Once evidence has been gathered through observation and interpretation, the teacher then makes a judgement on the next course of action to move the learner forward.

While the three stages represent the core features of formative assessment, it is important to explain how they can be integrated into practice. Bennett [21] and Leahy and William [35] describe five key elements for the effective translation of formative assessment principles into classroom practice, as follows:

- Sharing Learning Expectations: Ensuring the learner knows what they are going to learn and the success criteria to achieve this goal.

- Questioning: Using effective questioning to facilitate learning.

- Feedback: Providing feedback that enhances learning within the moment.

- Self-assessment: Allowing learners to take ownership of, and reflect on, their learning.

- Peer assessment: Providing opportunities for learners to discuss their work with, and to instruct, others.

Given that there are limited examples of economic methods being used as part of evaluations of education programmes, the formative assessment implementation project (FAIP) delivered to schools in north Wales provided an opportunity to trial the application of EAEI using a cost methodology used in health economics on a medium-to-large-scale school improvement initiative. This study aimed to answer the following research questions:

RQ1:

What is the impact of the formative assessment implementation project (FAIP), and does this represent value for money?

RQ2:

What is the feasibility of using health economics approaches to evaluate a large-scale education programme in schools?

3. Methods

3.1. Trial Design

The evaluation was based on a mixed methods approach using a matched comparison pre-post quasi-experimental design, plus interviews with teachers and learners, to assess the impact of FAIP on learner outcomes. This was deemed the most appropriate approach to take as programme delivery with tier 1 schools was already underway at the start of this research and it was not possible to randomly allocate schools to different conditions [36]. This type of research design has also been used extensively in large-scale evaluation studies and for policy implementation studies, including public health research, in which researchers have little control over the allocation of groups of participants [37,38,39].

3.2. Recruitment

All primary schools in this study were in the second tier of FAIP and were invited in September 2018 to participate in the research study. A purposeful sampling approach was used to identify schools willing to engage with research [40]. School improvement advisers from the North Wales Regional School Improvement Service (GwE) identified 35 schools that had previously engaged in school-based research and were also part of FAIP tier 2. Ten schools were recruited for the intervention arm of the research and a matched sample of 10 control schools was identified using language of instruction, size and socioeconomic characteristics (as represented by the percentage of learners eligible for free school meals [% e-FSM]) as matching criteria. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the schools in both arms of the study. Two schools in the control group and one school in the intervention group failed to provide follow-up data and were omitted from the study. The final study consisted of nine schools in the intervention group and eight schools in the control group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating schools.

3.3. Study Population

This study focused on 249 learners from Years 4, 5 and 6 (age 8–11 years) in 17 primary schools in North Wales (Table 2). In the intervention schools, only learners in a class where the teacher had attended FAIP training were included in the analysis, and their progress was compared with learners in the matched control schools. Some parents did not provide consent for their child’s data to be included in the study, so there is an imbalance in the group sizes. This population was chosen because primary school settings enable learners to be taught mainly by the same class teacher throughout the year and, therefore, it was more likely that these teachers would be able to provide a more consistent delivery of the core strategies within the FAIP intervention. Additionally, the measures employed for this research were not valid for learners under 8 years of age. One teacher from seven of the intervention schools also participated in the study (Table 3). Informed parental consent and learner assent was gained for quantitative and qualitative data collection, and teachers consented to participate in the research. Ethical approval was granted for this study from Bangor University Psychology Ethics and Research Committee (application number: 2018-16324-A14505).

Table 2.

Ages of primary school learners in each group.

Table 3.

Characteristics of teachers participating in follow-up interviews.

3.4. Outcomes

The study collected information on learners’ National Reading and Numeracy personalised assessments from the 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 academic years. Learners are assessed on their reading comprehension skills in either Welsh or English (depending on their language of instruction) and two numeracy assessments: the Numeracy (Procedural) assessment focuses on measuring data and number skills and the Numeracy (Reasoning) assessment focuses on learners’ ability to complete problem-solving tasks [41]. The results of the test are presented as an age-standardised score that compares each learner with other children in Wales born in the same year and month who took the assessment at the same time of the year (M = 100, SD = 15) and a progress measure which compares a learner’s outcome with all of the other children in their year group across Wales who took the assessment at the same time of the year (M = 1000, SD = 20).

In addition to national assessment outcomes, the study used three validated questionnaires to explore the impact on learners’ quality of life and wellbeing. Formative assessment has been linked to improved pupil behaviour, self-regulation, and non-cognitive improvements [22,42], and it was deemed appropriate to try to capture these outcomes in this study. First, the Child Health Utility-9D (CHU-9D) measure focuses on health-related quality of life. CHU-9D covers nine domains: worried, sad, pain, tired, annoyed, schoolwork, homework, daily routine, and the ability to join activities, with five levels of response within each domain [43,44]. CHU-9D is available in multiple languages, including a Welsh version, enabling learners to respond in their preferred language.

Second, the study used the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) for learners aged 4–16 years and which identifies social and emotional wellbeing as well as behavioural difficulties [45]. SDQ consists of 25 questions covering five domains: emotional, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems and pro-social behaviour. The questionnaire has been translated into multiple languages, including a Welsh version, enabling learners to respond in their preferred language.

Finally, the third questionnaire was the Quality of Life in School Questionnaire (QoLS) [46]. This covers four main domains: teacher–student relationship and social activities (12 items); physical environment (11 items); negative feelings towards school (eight items); and positive feelings towards school (five items). The QoLS questionnaire has a four-level response rating and is primarily aimed at measuring learners’ wellbeing and satisfaction at school [47]. This questionnaire has been translated into American English. Through consultation with the developers, revisions were made as some specific terminology is not used in the UK (i.e., grade and homeroom). At the request of the developers, the revised version of the questionnaire was translated into Welsh and then reverse-translated back to English to check for accuracy. The Welsh language version was approved by the developers.

The qualitative element of the evaluation included semi-structured interviews with class teachers and focus group interviews with learners to understand their perspectives on the teaching approaches involved in FAIP.

3.5. Analysis

The primary outcome measure for the quasi-experimental part of this study was the gain score (or difference) between the mean pre- and post-test assessments. The gain score was judged to be an appropriate output as it accommodates any imbalance in the baseline performance of the two groups. Due to data sharing protocols, learner outcomes were anonymised and aggregated at class level and no additional learner demographic information was available. This limited any further regression analysis. The analyses here are based on Hedges’ g effect size, using the difference in the gain scores between the groups divided by their pooled standard deviation. As there was no random allocation used in this study, there is no need to report p-values or confidence intervals [48,49].

For the National Reading and Numeracy personalised assessments, data were provided for the 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 academic years. We used the standard deviations provided by the test developer (SD = 15 and SD = 20 for the age-standardised and progress measures respectively). For the CHU-9D, SDQ and QoSL measures, pre-tests questionnaires were administered in the autumn term 2018, and post-tests were collected in the summer term 2019. We calculated the pooled standard deviation for both groups. Sample sizes varied for CHU-9D, SDQ and QoSL due to missing cases, and only complete cases were used in the analysis. All of the scores presented in this study, including effect sizes, are rounded up to two decimal places. Effect size estimates derived from the National Reading and Numeracy personalised assessments are reported according to a schema described by Gorard and Gorard [49]. Questionnaires were administered through an online survey tool (Online Survey) and were available through the medium of the Welsh and English languages. Paper copies were also available for participants to use.

3.6. Interviews

Interviews were conducted with teachers to gather their feedback and experiences after implementing FAIP. Interviews were also used to collect additional information about the time and cost implications of using FAIP strategies in the classroom. Details of the seven participating teachers are shown in Table 3. Two teachers were not interviewed due to illness and other commitments.

3.7. Focus Group

Focus group interviews were used to explore learners’ perceptions of the impact of the teaching strategies contained within the intervention. All learners with parental consent were chosen at random by their class teacher to participate, and learner assent was also gained before the focus groups commenced. Fifty-seven Year 4, 5 and 6 learners (age 8 to 11 years) from eight intervention schools participated, representing a mixture of Welsh and English medium settings. All interviews and focus groups were conducted in school settings either in the classroom or a suitable, quiet room free from disruption.

3.8. Procedure

Discussions took place with the class teacher prior to the focus group interviews to clarify the main strategies that had been used in class following FAIP training. This allowed the researcher to clarify the nature of the focus group questions. For example, if the class teacher implemented talk partners, learners would be asked “can you explain what a talk partner is?” followed by “how did you find this new way of working?” additional prompts would be used “do you like this way of working?” or “did you find this helped with your work?” Questions were as open-ended and non-directive as possible so that learners felt able to provide their opinions rather than responses that they may perceive as more socially acceptable [50]. Each focus group was composed of between 6 and 8 participants and lasted between 15 to 40 min. Before each focus group discussion commenced, the researcher clarified the purpose of the research and co-constructed the ground rules, including a demonstration of the recording equipment. Learners were informed that they could leave at any time should they no longer wish to participate. Questions were designed to give an insight and understanding of learners’ experiences of using the FAIP strategies in class, to provide information to help evaluate the outcomes learners achieve, and to provide time for learners to freely discuss their experiences and opinions.

3.9. Observations

Although there are no standardised observation checklists available for observing the quality of teachers’ use of formative assessment in classroom settings, a checklist document used by Leahy and Wiliam [35] was used in the current study. Observing the ongoing and often iterative nature of formative assessment in classrooms would not have been feasible due to resource limitations, so it was decided that a single observation would be made in each intervention classroom. The observation checklist consisted of 16 statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale relating to formative assessment practices as follows [35]:

- Is it clear what the teacher intends the students to learn?

- Does the teacher identify student learning needs?

- Do students understand what criteria will make their work successful?

- Are students chosen at random to answer questions?

- Does the teacher ask questions that make students think?

- Does the teacher give students time to think after asking a question?

- Does the teacher allow time for students to elaborate their responses?

- Is a whole-class response system used?

- Is teaching adjusted after gathering feedback from pupils (data collection)?

- Is there more student talk than teacher talk?

- Are most students involved in answering questions?

- Are students supporting each other’s learning?

- Is there evidence that various forms of teacher feedback advance student learning?

- Do students take responsibility for their own learning?

- Does the teacher provide oral formative feedback?

- Does the teacher find out what the students have learned before they leave the room?

To gather a more impartial and accurate assessment of the quality of teachers’ use of formative assessment strategies, GwE school improvement advisers were trained how to use the observation checklist. All of the advisers were either experienced head teachers and/or qualified school inspectors. The training consisted of a 30 min session that explained the purpose of the checklist and how it was designed to be used. The observations took place in the school setting and consisted of teachers being observed for up to 30 min delivering one lesson (literacy or mathematics). Each teacher in the intervention arm consented to the observation and nine teachers were observed. Observations were rated on the following five-point scale: not applicable, applicable but not observed, observed but poorly implemented, observed and reasonably implemented, or observed and well implemented. Observation checklists were available in Welsh and English depending on the language of instruction. The observation ratings for each statement were added together and an overall percentage score was calculated for the nine classrooms.

4. Intervention

This study focuses on the evaluation of a regional professional learning initiative called the Formative Assessment Implementation Programme (FAIP) delivered in the UK by the North Wales Regional School Improvement Service (GwE). FAIP was designed to help teachers identify and use more effective formative assessment strategies to help learners make progress and was focused on the delivery of domain general teaching strategies that could be used across the curriculum and throughout the school day. FAIP was designed to promote effective pedagogy; help reduce workload by enabling teachers to make use of more efficient feedback strategies; support schools to deliver the Curriculum for Wales [51]; and, to raise standards in schools across the region.

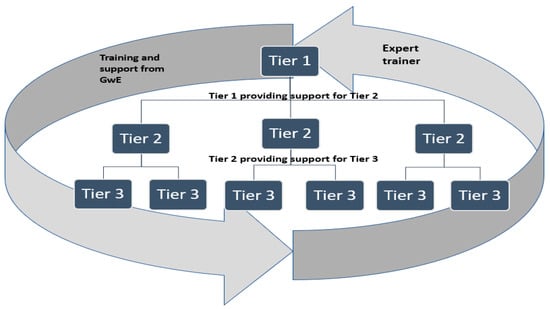

FAIP consisted of a three-year school improvement project working with three cohorts of schools from 2017 to 2020. The first year the programme consisted of initial training sessions delivered by an expert in formative assessment to an initial group of schools (known as tier 1 schools). In the second year of the project, these schools provided mentoring and support to a second wave of tier 2 schools through a train-the-trainer approach. In the third year, these tier 2 schools provided mentoring and support to a final cohort of tier 3 schools. GwE school improvement advisers supported the work of all schools in each tier throughout the duration of the project. Figure 1 shows the three implementation stages and structure of FAIP. This study focuses on an evaluation of costs and outcomes in tier 2 schools.

Figure 1.

The three implementation stages and structure of FAIP.

In October 2017, two teachers from each of the 27 tier 1 schools attended two FAIP training sessions led by the expert trainer and attended follow-up review sessions with GwE school improvement advisers to reflect on the fidelity of implementation of teaching strategies. These tier 1 teachers then worked collaboratively to implement the formative assessment strategies within their classrooms for the remainder of the academic year. In the 2018–2019 academic year, 386 teachers representing 193 tier 2 schools attended a FAIP training session led by the expert trainer alongside five training and implementation support sessions lead by GwE school improvement advisers (September, November, January, April, and June). In the 2019–2020 academic year, the remaining 140 schools in the region formed tier 3 of the project and were invited to attend introductory FAIP training with the expert trainer and receive support from tier 1 and tier 2 schools. Due to disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, tier 3 teachers received most of their training and support online. As part of a train-the-trainer model, teachers from all tiers were encouraged to share good practice and utilise support and guidance from other schools in the project. These collaborative review sessions were designed to share effective practice, discuss progress, and allow teachers to receive feedback on their experiences. Finally, a series of showcase events was organised to enable teachers to present the work they had undertaken in school. Table 4 shows the chronology of FAIP and the number of schools involved in each tier.

Table 4.

Chronology of FAIP * and number of schools involved in each tier.

The introductory FAIP training session led by the expert trainer contained a wide range of evidence-informed formative assessment strategies and techniques [19,20,21,24,35]. Table 5 shows the core principles of effective formative assessment contained within the introductory session, alongside the key implications and suggested teaching strategies for teachers. Although all teachers received information on all of the aspects outlined in Table 5, they could focus on using any of the strategies in school as part of their everyday teaching.

Table 5.

Summary of the formative assessment principles and practical teaching strategies delivered in the FAIP * training session.

5. Economic Analysis of Educational Interventions (EAEI)

5.1. Cost-Consequence Analysis

The study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of FAIP and test the feasibility of using economic methods in an educational context. Economic evaluation, in its simplest form, is a balance sheet of the costs and benefits (effects) of an intervention [52]. There are five main types of economic evaluation commonly used in health economics evaluations: cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), cost-utility analysis (CUA), cost-benefit analysis (CBA), cost minimisation analysis (CMA) and cost-consequence analysis (CCA) [52]. A cost-consequence analysis was chosen as the most appropriate evaluation tool for this study as it allows the decisionmaker to review the disaggregated evidence and prioritise which costs and outcomes are important to their context [53]. In the following sections we explore the utility of using CCA methods.

5.2. Rationale for CCA

CCA is recommended for use in the evaluation of provision in public health and non-health settings as it allows flexibility to capture the economic implications of a broad range of outcomes [54,55,56]. Coast [57] suggests that CCA is a more useful form of economic evaluation, particularly for social decision-making, where it is often suited to non-technical audiences and presents costs and outcomes in a disaggregated way [56]. There is a challenge when evaluating complex interventions that are often characterised by multiple components that can be subject to adaptation depending on the stakeholder needs and/or local conditions. Within complex interventions, there is an additional challenge of quantifying benefits and outcomes into monetary values, and omitting this information due to the difficulty in calculating monetary risks limits the range and scope of information available to decisionmakers [58]. Hummel-Rossi and Ashdown [7] have suggested that the ‘qualitative residual,’ or the additional benefits that are difficult to quantify in financial terms, should be included where possible to support decisionmakers within educational research.

Given the complex nature of the intervention being evaluated in this study, a CCA was deemed most appropriate to evaluate costs and outcomes, particularly given the difficulty of placing monetary values on some outcomes in this study. Using CCA also allows decisionmakers to decide what outcomes are relevant to their context or objectives. The FAIP intervention can be considered complex given the nature of the training and the fact that teachers were able to adapt the intervention to suit their school context. Each school setting is represented by different staff experiences and abilities, ethos, structures and environment, and this adds an additional layer of complexity to the challenge of delivering FAIP training at scale across six local authority areas via a train-the-trainer approach [58,59]

5.3. Cost Collecting Methodology

Cost collecting methodology in health falls into two broad categories, known as top-down or bottom-up approaches. Top-down methods require retrospective costing to secondary data to calculate costs (sometimes called relative value units [RVU]). Although this is a useful costing method when resources do not allow for in-depth costing, it can limit the precision of costing [60]. Bottom-up costing, sometimes termed activity-based costing (ABC), involves calculating, at item level, the costs associated with running an intervention or treatment and can be advantageous for the transferability to different sites or treatment pathways [52]. Applying different methods for estimating costing can produce different results, therefore it is important for the analyst to determine the most appropriate cost-collecting methodology. For example, if the analysis is not concerned with variation of local cost, then a top-down approach would be suited, but if the variation on a local level is a consideration, then a bottom-up approach may be more appropriate [60]. In this study, the majority of costs were incurred by GwE as the body that commissioned, organised and supported schools to engage with the project (e.g., costs to cover teachers’ attendance at the training and to cover GwE staff costs). It was therefore more appropriate to collect the cost from the perspective of GwE and that this should be considered a bottom-up methodology.

5.4. Collating Costs

One of the main challenges in collecting costs for economic evaluation in education is in quantifying the opportunity cost of using teaching staff to deliver a programme or intervention [61]. Education research currently lacks a recognised protocol for the identification of established costs, especially around the collection of opportunity costs. Therefore, a pragmatic approach was used in this study to calculate the cost of business as usual (BAU) for teachers. As this is a bottom-up approach, it was important to calculate the on-costs associated with teachers’ time and the costs of the necessary equipment and support they require to carry out their duties. To collate the cost of teachers’ time, costs were collected from three local authorities in North Wales (Anglesey, Conwy, and Wrexham), and additional information on maintenance costs and the costs of school services was gathered. Together, these data provided a cost for a teacher to stand in a maintained classroom with the necessary equipment for one year. Information on national teacher salary scales was used to calculate a mean salary for qualified teachers, including additional teaching and learning responsibilities (GBP 27,018–GBP 41,604, scale M2 to Max-U3 at 2020 rates). Salary scales for school leaders were excluded from this analysis. Additional information on teacher on-costs (including the cost of pension and National Insurance [NI] contributions) were taken from a previous study by Harden [62]. In Wales, teachers are contracted to work for 1265 hours a year [63], so the annual salary cost was divided by 1265 to calculate the cost per hour and the per pupil calculation was based on the average class sizes in three regions of Wales where the study took place (18.5 learners per primary school class). Table 6 shows the costs of teachers’ time, including on-costs, which forms the BAU comparison used in this evaluation.

Table 6.

Salary cost for a qualified teachers’ time (including on-costs).

5.5. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis is an important component in economic evaluations. It addresses the inherent uncertainty in costs and key parameters and helps explore how the assumptions made by the analyst might affect outcomes. In health economics, sensitivity analysis allows researchers to explore how changes in input variables can influence the outcomes of their analyses. Given that costs can vary widely, it is essential for researchers to be transparent about how they have identified costs and the assumptions that they have made [64]. By doing so, they can provide a clearer understanding of the robustness and reliability of their findings and, therefore, improve the trustworthiness of the findings.

6. Results

6.1. Learner Outcomes

In this section we report the outcomes of the primary and secondary analysis of learner outcomes in the FAIP intervention schools compared with the matched control schools that followed business as usual approaches.

It was not possible to obtain follow-up National Reading and Numeracy personalised assessment outcomes for one learner in one intervention school and three learners in two control schools. As a result, there were 245 learners in the final analysis of attainment outcomes between the two groups (Table 7). The results show that learners in the intervention group made negative progress (i.e., lower mean scores after one year) on all of the reading and numeracy assessments except for the Welsh progress score. However, learners’ English and Welsh scores showed a smaller decline between pre- and post-test than the control group, resulting in small to medium effect sizes for these three outcomes (+0.12, +0.15 and +0.08).

Table 7.

Primary analysis using National Reading and Numeracy personalised assessments.

Table 8 shows the mean and standard deviation results for the CHU-9D, SDQ, and QoLS measures as the secondary outcomes analysed. The CHU-9D measure had a completion rate of 80% for the intervention and n = 24 cases were removed, leaving n = 94 full cases for analysis. The completion rate for the control was 79%, with n = 29 removed, leaving n = 110 full cases to be analysed. SDQ measure had a completion rate of 73% for the intervention schools and 66% for the control schools. The total number of cases removed from the intervention was n = 32, leaving n = 85 full cases for SDQ analysis. For the control, n = 47 cases were removed, leaving n = 92 full cases for SDQ analysis. QoSL measure had a completion rate of 59% for the intervention group and 51% for the control group. The total number of cases removed for the intervention was n = 49, leaving n = 69 full cases for QoSL analysis. The total number of cases removed for the control was n = 68, leaving n = 70 full cases for QoSL analysis. Learners in the intervention group made greater negative progress on all of the quality of life and social and emotional wellbeing measures than learners in the control schools (effect sizes of –0.21, −0.22 and –0.39, respectively, for the three outcomes).

Table 8.

Results for CHU-9D, SDQ and QoLS outcomes measures.

6.2. Classroom Observations

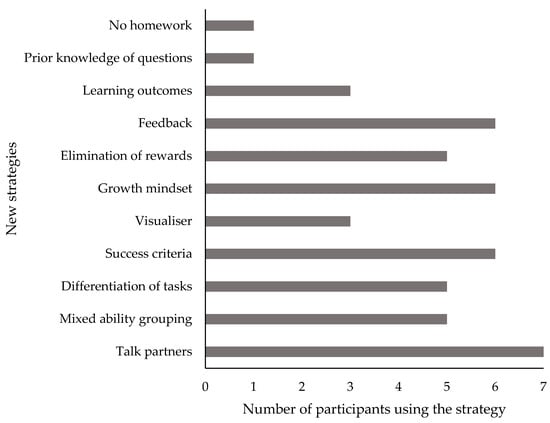

Nine teachers were asked what strategies from the FAIP training they had implemented in the classroom. Figure 2 shows the frequency of the formative assessment strategies that the teachers used in their classroom during the year following FAIP training. The most common strategy used by seven teachers was talk partners, followed by six teachers using success criteria, growth mindset and feedback strategies.

Figure 2.

Teachers’ use of formative assessment strategies following initial FAIP training.

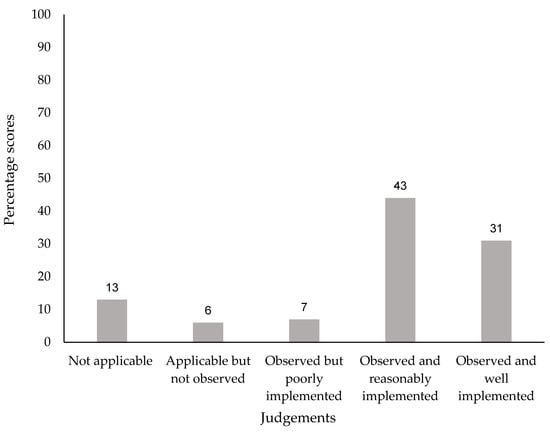

Figure 3 shows judgements on the quality of teachers’ implementation of formative assessment strategies in class. In each of the nine sessions observed, teachers were assessed using a 16-point observation checklist recorded using a 5-point Likert scale adapted from Leahy and Wiliam [35]. Judgements were added together to calculate an overall percentage score for the quality of implementation of formative strategies across all nine classrooms. The findings indicate that, in the intervention arm, many of the main formative assessment principles were observed as being implemented either reasonably well or better.

Figure 3.

Judgements on the overall quality of implementation of formative assessment strategies in nine intervention classrooms.

6.3. The Opinions of Teachers and Learners

Interviews were conducted with seven class teachers to explore aspects of FAIP in more detail. All interviews were conducted in English and took place in school. A thematic analysis approach was used that enabled the identification of key themes [65]. Thematic analysis provides a systematic way of organising qualitative information into themes representing patterns of meaning with the goal of understanding and describing the social reality of the topic under investigation. The themes generated allow for the perceptions and experiences of groups of participants to be examined and themes were developed across the whole sample rather than for each individual participant [66]. In this study, an inductive thematic analysis approach was used as described by Braun and Clarke [66].

6.4. Interviews with Teachers

Thematic analysis identified the following seven themes:

Learners focused on learning: All teachers mentioned that the strategies they employed allowed learners to engage with, and complete, tasks more independently and improve their readiness to learn. Teachers also reported that learners could self-assess and reflect on their work more effectively.

Understanding where learners are in the learning journey: All teachers agreed that the strategies helped them know where the learners were in their learning and helped provide them with a more complete understanding of each learner. Teachers were also able to identify which learners needed support much quicker and adapt teaching in real time to support any misconceptions that learners had within the learning process.

“…helps me feel I get a greater understanding of my children. And I don’t go home at the end of the week thinking, I don’t think I’ve said five words to that child.”Teacher 6

Self-efficacy: Teachers described how learners in their class had developed increased levels of self-efficacy and were able to challenge themselves to do tasks they were previously hesitant to complete. Teachers also found that learners were more confident to contribute and share ideas with the class.

“And sometimes it can be a little bit of idleness of picking up a pen but sometimes it’s their belief in themselves a lot of the time. And it is, it’s them thinking, “actually, I can do it”. “I think a lot of it is the confidence they have…”Teacher 4

Improved Behaviour: All of the teachers commented on the dynamics of the classroom and how it had changed to become a more inclusive setting where no learners felt excluded. “I found there was less fighting, or less arguing outside …” Teacher 2

Reduced workloads: All of the teachers identified that the appropriate use of a wider range of feedback strategies enabled them to reduce their marking workload and had improved the standards of learners’ work. In turn, this had allowed them to make more effective use of written feedback to learners.

“So, it’s easier. I think the quality of work is easier to mark…I do feel I’ve got extra time.”Teacher 2

Improved standards: Teachers identified improvements in the standards learners achieved during the intervention, particularly through the use of success criteria, talk partners and/or peer- and self-assessment strategies. Teachers also identified a positive impact on the standards achieved by struggling learners.

“I would say predominantly it’s that the lower achievers it’s had the bigger impact on.”Teacher 5

Prepared for the new curriculum: Teachers identified a positive link between formative assessment strategies and the 12 pedagogical principles in the context of the four purposes set out in the Curriculum for Wales [67]. A number of teachers felt that their participation in FAIP was effective preparation for understanding and delivering the Curriculum for Wales.

6.5. Focus Group Interviews with Learners

Focus groups were conducted with 57 learners from 8 intervention schools. All focus groups were conducted in English and learners were asked about their understanding of the strategies their class teacher had used over the academic year. They were also asked about the perceived impact, if any, on their learning. The following seven themes were identified:

Talk Partners: Learners understood what a talk partner was and were able to see that the strategy had other impacts, such as academic support and social relationships. Learners discussed copying as a challenging issue between some pairs of children. Some learners indicated they would become annoyed at other children looking at their work and the perception of imbalance in the pairing of talk partners in class. There were also perceptions of uneven workload distribution during peer working.

“You kind of get to know them more, cos like…you just like…you don’t really play with them, cos you like different things, but if you’re discussion partners, you might have to try and get to know them…You might think better of them.”Learner, school L

Mixed ability grouping and differentiation of task: Learners were aware of what ‘group’ they were in if they were sitting with a higher or lower-attaining learner and how this could support each other’s learning. There were incidents where learners explained that there were some negative consequences for both the higher and lower attaining learners, but overall these strategies allowed them to focus on their work and understand where they were within their own learning journey.

Elimination of comparative rewards: Learners in two focus groups discussed how the rewards were being used to encourage them to complete work and monitor behaviour. Some of the responses alluded to the fact that the use of rewards did not necessarily focus learners on their learning, but instead that they were motivated simply to receive a reward. The learners commented that, without the reward system, they would be more likely to focus on the academic task in hand and would seek feedback in other ways to support their learning. These learners also noted that removing the rewards would create a more equitable classroom climate.

Growth mindset: Learners were able to identify how the introduction of this strategy in the classroom impacted the quality of their work, their perception of self-efficacy and on the development of a more positive manner with which they could engage with their work.

Success criteria: Learners described how to create task-based success criteria, and how it helped them to complete tasks more successfully. Learners also discussed how the use of success criteria enabled them to stay on task and identify where improvements can be made.

“It makes the work a bit more straight forward, Cos when you look at the success criteria when you’re working, then it like gives you more to think about it and then more to think about the work.”Learner, school P

Feedback: The feedback strategies allowed learners to better understand the progress of their learning, identify mistakes, and allowed them to be a helpful learning resource for each other.

“…the teacher will take you out of the lessons and things just to like go over your piece of work and if you’ve done something well, he’ll tell you what you’ve done well and he’ll like highlight it on the success criteria, which is a list of things that you have to do and he’ll highlight it pink and then if you need to do something better, he’ll highlight it green and then he’ll tell you to re-do it and he’ll tell you what to re-do and stuff.”Learner, school O

Meta-cognition: Learners discussed how using a shared language of learning that is related to tasks helped them improve the quality of their work. Some learners were able to use this shared language to retrospectively assess their work.

The main findings from discussions with teachers and learners are organised around the five central principles of effective formative assessment as follows:

Sharing Learning Expectations: Ensuring the learner knows what they are going to learn and the success criteria to achieve this goal.The teachers discussed how FAIP supported them to help learners better understand the nature of successful outcomes and understand the expectations of quality standards in their work. Additionally, learners described how success criteria helped them complete tasks more successfully.

Questioning: Effective questioning to facilitate learning.Teachers identified how using the strategies contained within the FAIP training helped them better understand where the learners were in their learning and provided them with useful, additional information to plan next steps. Teachers also indicated that they were more able to identify which learners needed support and adapt teaching in real time to provide next steps advice and support to learners.

Feedback: Provide feedback that enhances learning within the moment.Teachers discussed how feedback strategies supported them to better understand learner progress. Some teachers discussed being able to give immediate feedback to support learners to improve the outcomes they achieve.

Self-assessment: Allowing learners to take ownership of, and reflect on, their learning.Learners identified how the use of a range of self-assessment strategies impacted positively on the learning process and how it helped them engage with, and complete, tasks more successfully.

Peer assessment: Providing opportunities for learners to discuss their work with, and to instruct, others.Teachers identified improved opportunities for learners to discuss their own work to enhance understanding and knowledge. Learners understood what a talk partner was, and how it helped them with their learning. It also enabled them to provide support for other learners. Learners also identified how it improved social relationships in school.

6.6. The Full Economic Cost of FAIP for Tier 2 Teachers

Table 9 shows the full economic cost of delivering FAIP training and support to 342 tier 2 teachers in 2018–2019. FAIP was implemented in the academic year 2019–2020, and costs have been inflated to 2022–2023 prices in the final column of Table 9 using Bank of England inflation calculator.

Table 9.

Full Economic Cost of FAIP for tier 2 teachers in 2018–2019.

6.7. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted on three different parameters to test the assumptions of the costing methodology detailed in Table 10. Testing assumptions can support robust conclusions in economic evaluations [68]. Costs have been inflated to 2022–2023 prices in the final column of Table 10 using Bank of England inflation calculator.

Table 10.

Sensitivity analysis.

The fixed teacher costs, alongside other project costs (for example, resource, translation, training and venue hire), represent the actual costs to deliver FAIP. The costs may vary when replicating the programme in another area. There are some uncertainties over assumptions made on three main costs.

6.7.1. Sensitivity Analysis 1

The average class size in Wales was 25 learners [69], and it was assumed that for each teacher trained, 25 learners would be exposed to the intervention. For comparison, sensitivity analysis was conducted on average class sizes of 20 and 30 learners. Changing the class size to 20 resulted in GBP 90.73 per-pupil cost and increasing the class size to 30 reduced the cost per pupil to GBP 60.08. Therefore, we can expect the cost to range between GBP 90.73 and GBP 60.08 depending on class size (at 2022–2023 prices).

6.7.2. Sensitivity Analysis 2

The teachers incurred out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses, mainly to purchase books and materials to support the dissemination of formative assessment in their setting. The OOP expenses were not mandatory but supported teachers’ professional development in this area. Sensitivity analysis was conducted assuming that all teachers in the study incurred OOP expenses. Results suggest that the per-pupil cost would increase from GBP 72.34 to GBP 74.46 if teachers incurred additional OOP expenses (at 2022–2023 prices).

6.7.3. Sensitivity Analysis 3

GwE provided a flat rate to cover teacher supply costs (GBP 250 per day and GBP 125 for a half day). The cost of a teacher’s time is a non-standardised cost that is likely to vary between different education settings. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to calculate the cost to cover teaching staff using the costs calculated for teachers’ time outlined in Table 7. Using BAU rates for teachers’ time increased the cost by GBP 10.87 from GBP 72.34 to GBP 83.21 (at 2022–2023 prices).

6.7.4. Sensitivity Analysis 4

Teachers in the second tier attended a final showcase event for half a day. Although there was no funding provided to cover the cost of attending this event, there would have been an opportunity cost. Sensitivity analysis was conducted on the opportunity cost of attending the showcase using three scenarios, as follows. First, the core programme costs outlined in Table 10 plus the BAU cost for teachers to attend the showcase event. Second, the core programme costs outlined in Table 10 plus the supply costs provided by GwE to attend the showcase event. Finally, the cost of the programme using BAU costs for teachers to attend the showcase event as well as BAU costs for all other teacher activities. The results indicate that if the opportunity cost of teachers attending the final showcase event was taken into account, the per-pupil cost would fall between GBP 76.18 and GBP 88.36 (at 2022–2023 prices).

7. Discussion

In this paper we have evaluated the impact of a regional professional learning project designed to improve teachers’ understanding and use of a range of formative assessment principles. We used a mixed method quasi-experimental design, including an economic analysis, to explore the impact of a regional formative assessment programme on a range of learner outcomes. The following discussion is focused around the two research questions.

RQ1:

What is the impact of the Formative Assessment Implementation Project (FAIP), and does this represent value for money?

The study found a medium, positive effect on learners’ English language skills in the intervention schools, and a medium positive effect on learners Welsh progress score. However, it is important to note that, although learners’ English scores declined in both groups from pre to post, the difference in reduction over time in the intervention group effect is smaller by +0.12 and +0.15 for the age-standardised and progress scores respectively, suggesting some benefit to the learners in the FAIP group. The baseline English scores were very similar for both groups and the school demographics were also closely matched. Therefore, excluding any confounding school effects, this indicates a degree of trustworthiness in this finding. In contrast, the baseline scores for the Welsh assessments were dissimilar, indicating an imbalance in their baseline language skills and the need to treat the finding for the Welsh progress score with caution. There were medium, negative effect sizes for the numeracy age-standardised and progress scores (−0.10 for both outcomes), and negative effects for the three non-standardised quality of life and wellbeing outcomes (−0.21, −0.22 and –0.39 respectively) (Table 7 and Table 8). It is not entirely unexpected to observe a greater impact in learners’ language skills compared with numeracy outcomes, as previous research evaluating the use of formative assessment for mathematics teaching has shown limited impact on learner outcomes [70], and there is further evidence to suggest that teachers find formative assessment challenging to use during mathematics instruction [71]. Furthermore, there is some evidence from this study to show that the formative assessment strategies and techniques were more commonly used to support language-specific tasks and to help learners improve the quality of their written work across the curriculum (for example, sharing success criteria and examples of learners’ work, and redrafting for improvement). As such, learners might have been able to engage with, and understand, a greater range of curriculum content that helped improve their reading skills. In contrast, it is not unexpected that there was no improvement in learners’ quality of life and wellbeing outcomes, as FAIP was not designed to specifically improve these domains. It is also possible that systemic, external factors might have affected how learners perceived their quality of life. Observational data suggest that the formative assessment strategies were implemented either reasonably well or better by teachers as part of their everyday teaching.

The cost of implementing FAIP to 323 tier 2 teachers was GBP 72.34 per pupil (converted to 2022–2023 prices) associated with an effect size of +0.12 and +0.15 for the English age-standardised and progress scores, respectively. This per-pupil cost also falls within the ‘medium effect size and low cost’ category outlined in Kraft [9]. Kraft [9] identifies GBP 436 (converted and inflated to 2022–2023) to be a low per pupil cost for interventions. This is an important finding and indicates that FAIP can be considered a low-cost, promising approach to help teachers and learners improve outcomes in schools. As well as considering cost and impact, Kraft [9] identifies the need to consider the scalability of the approach or intervention. Interventions tested during small scale efficacy trials (that may have had large effect sizes) can often produce smaller effects when delivered at scale, due to the challenges associated with maintaining fidelity during wider roll out without specialist training and support. Policymakers need to consider whether a programme can be delivered at scale, including an appreciation of the barriers and facilitators that schools might encounter when implementing the approach. More complex interventions frequently require sophisticated implementation plans and are more difficult to take to scale [9]. However, FAIP required teachers to consider the use of a suite of practical, evidence-informed teaching strategies that required minimal behavioural change to enable teachers to implement them to a good standard. Additionally, the initial FAIP professional learning sessions followed a relatively simple format and were supported by widely available professional learner materials for teachers [19,20]. It was also possible to divide schools into three intake cohorts and use teachers as part of a train-the-trainer support model. This indicates that FAIP has the potential to be scaled up.

Information from teachers and learners shows that the FAIP intervention schools found important, positive impacts in both the quality of teaching and learner experiences. After initial training, teachers used many of the formative assessment teaching strategies to a good standard in class. In turn, teachers identified positive impacts on the quality of classroom learning environments and a concomitant improvement in the standards learners achieved. An important feature of the findings was a reduction in teachers’ workload facilitated by the more effective use of a range of formative assessment strategies, including a reduction in the volume of time-consuming, written feedback in learners’ books. This is an important outcome, especially in the context of teacher workload and burnout [72]. Learners reported important positive benefits to the quality of the learning environment in class and a positive impact on the standard of their work. In particular, teachers’ effective use of feedback strategies, together with more task-specific success criteria, were deemed successful features. Learners also discussed how the strategies helped them to understand the features of successful outcomes and indicated that it helped them improve the quality of their work.

The costs and impact data presented in this study can be compared with other programmes where similar information is available. Gorard, Siddiqui and See [73] have made comparisons of ‘catch up’ programmes for secondary school learners, including the ‘effect’ sizes and costs for a range of interventions. An adapted version of the original table of comparative programme costs and impacts is presented in Table 11, with costs inflated to 2022–2023 prices to enable comparison with FAIP. While FAIP is a regional professional learning initiative rather than a ‘catch-up’ programme, it is designed to improve the quality of teaching and, therefore, learner outcomes through the dissemination and use of a suite of effective teaching strategies that can be used across the curriculum. The findings presented in this paper show that FAIP has a positive impact on teachers’ skills and learner outcomes, and that the effect size and per-pupil cost compares very favourably with comparable programmes such as summer schools and Switch-on (a reading programme).

Table 11.

Comparison of programme costs and impact adapted from Gorard, Siddiqui, and See [73].

However, there is a need to exercise caution when comparing the FAIP costs to the ‘catch up’ interventions presented in Table 11. The costs included in the estimates presented by Gorard, Siddiqui and See [73] are estimates and not full economic evaluations. This reflects the current lack of robust cost collecting methodology in education that prevents researchers from making fair comparisons between programmes and approaches.

The EEF’s ‘Embedding Formative Assessment’ study is similar in scale and design to FAIP, and findings presented by Speckesser et al. [74] indicate that secondary school learners made up to two months of additional progress in a range of GCSE subjects after teachers had engaged with a formative assessment professional development programme. However, no impact was found in English and mathematics outcomes. The cost of the EEF ‘Embedding Formative Assessment’ implementation was GBP 1.20 per pupil based on a two-year implementation period and averaged over three years [74]. The current FAIP evaluation was based on one academic year, and we did not calculate discounted rates (maintaining the benefits over a longer term) for any subsequent years the teachers may have retained the formative assessment strategies and any longer-term impacts on learners [68]. Additionally, the EEF did not calculate the opportunity cost of teachers’ time or detailed cost breakdowns. Had the EEF included the opportunity cost, this would have increased the cost per pupil. Considering that opportunity cost is a core concept when undertaking economic evaluations, it is difficult to draw any meaningful cost comparisons between this study and the EEF study [12]. If discounted rates are applied to FAIP and projected over three years, the cost is reduced to GBP 24.11 per pupil (including the opportunity cost). However, it is important to exercise caution in interpreting this revised figure, as it assumes that teachers can maintain the use of these new skills over multiple years.

Although the present study and the EEF study both use different assessment outcomes, the findings suggest variable levels of impact following the introduction of formative assessment intervention programmes. This might be due, in part, to the limited duration of the intervention in this study (i.e., one academic year) and the more general aim of formative assessment initiatives to improve teaching and learning skills as opposed to targeting specific academic skills (e.g., English language skills). Additionally, the teachers involved in this study received training and input from both the expert trainer and other teachers as part of a train-the-trainer model. It is likely there was some variation in the quality and support available for tier 2 teachers and, by implication, variation in the quality of formative assessment practice within the classes in the intervention group.

The findings in this study underscore the benefits of helping teachers use good-quality formative assessment strategies, including improved understanding of learning goals, enhanced questioning techniques, effective feedback, and the promotion of self and peer assessment strategies. Importantly, these skills can be used by teachers and learners across the curriculum. While it is difficult to translate the qualitative findings into monetary values, this information suggests that FAIP has resulted in important positive benefits on both the quality of teaching learner independence, and the language outcomes they achieve. Unlike standardised outcomes measures, these less tangible outcomes are difficult to transfer to monetary values (for example, Newell, Pizer and Prest [75] converted improvements in exam results into predictors of future earnings). It is important for decisionmakers to appraise costs needed to help them decide if softer educational and/or well-being outcomes are important within the context of the improvement action and, therefore, whether it represents value for money. Using only information on effect sizes to compare programmes (as opposed to a combination of effect size, qualitative impact and cost) limits the concept of the impact of the intervention to one—often narrow—outcome measure [68]. Approaches such as EAEI provide a more accurate account of the costs to be presented alongside effect sizes and other qualitative data, and enables researchers and decisionmakers to assess concepts of value for money and impact in the context of the wider benefits to school staff and learners.

RQ2:

What is the feasibility of using health economics approaches to evaluate a large-scale education programme in schools?

This study has shown the feasibility of using a CCA methodology to improve the evaluation of a large-scale school improvement programme. This study took a pragmatic approach and provided an example for how other analysts might attempt to overcome the lack of standardisation of costs in education settings. Though the consideration of these costs is still in its infancy in education research, this study has shown the utility of collecting these costs whenever possible. We were able to collect accurate programme costs, which represent the actual cost to disseminate FAIP, alongside additional cost information from schools, to assess the cost to implement FAIP at school level. We also identified some challenges when applying these methods to education, including the lack of a standardisation of the cost of teachers’ time and the resulting difficulty in calculating opportunity cost and business as usual comparisons. In health economics research, the opportunity cost is dependent on the analyst’s perspective and the current economic frameworks being developed in education research recommend that opportunity cost be routinely included [12]. In the UK, the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) supports health economists to establish programme costs by providing a centralised cost repository to support accurate overall costings and, in turn, to provide consistency across a range of evaluations of other areas of education provision [76]. The findings of this study support the call for the creation of a centralised cost repository for education to provide standardised costs to researchers to help them improve the quality of evaluations [77]. We have attempted to mitigate this challenge by calculating the BAU or opportunity cost for teachers’ time in a robust way that could be used by other analysts who wish to conduct economic analyses of education interventions.

As this was a large-scale intervention that was evaluated over a relatively short time, it was challenging to identify outcome measures that would adequately capture the impact of the programme. FAIP was a teacher professional learning programme designed to improve the quality of teachers’ formative assessment skills and, therefore, it could be considered a domain general approach and not targeted to one subject area or skill (see discussion in [21]). However, this study used available national reading and numeracy assessment data as outcome measures, together with health, social and emotional and quality of life outcomes, as these were judged to be the most practical way of capturing the widest possible range of FAIP impact over the duration of the study. However, using national and other standardised assessment outcomes to support comparisons across different interventions and programmes is problematic, in part due to the challenge of capturing the sometimes nuanced variation of outcomes from programmes and interventions that focus on the same domain (for example, wellbeing programmes).

Though using programme-designed measures may allow large impacts to be identified, these are generally limited to the programme under investigation [9]. It is also important to use comparable outcome indicators, particularly when undertaking economic evaluations involving cost-effectiveness analysis, where two interventions with the same outcome indicators are used to make a comparison of costs and outcomes to aid decision making [52]. Developing this theme, health economists have developed the Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY) measure to provide a comparable outcome standard when comparing different programmes, even when the programmes target different outcomes. The QALY enables interventions to be compared across treatments and populations, and it has become a core tool that has improved the quality of healthcare evaluations and decision making [78]. Developing an education QALY might enable researchers to incorporate cost analyses in evaluations to help decisionmakers compare different courses of action where the focus of the intervention could be different, or the outcomes are not the same. At the moment there is no education QALY and this is why approaches such as EAEI are triangulated with information on effect sizes and process evaluation findings (such as the views and opinions of key stakeholders). The combined output will help researchers and decisionmakers identify the most promising approaches. It is important to note that this might not necessarily mean utilising the lowest cost programme, but it will require more a sophisticated consideration of the needs of the target population alongside cost, impact and ability to take the approach to scale.

The costs included for this study focused on the training and participation of tier 2 teachers (and the associated programme delivery costs) as opposed to the costs associated with all three tiers. Early identification of costs supports the scalability of interventions [79,80], and Levin and Belfield [81] and Scammacca et al. [61] recommend that economic evaluations should be conducted across all stages of programme evaluation research to help inform decisionmakers. This principle should routinely be applied at all stages of education research, for example, from early efficacy trials through to later phases of research on the journey to evidence [6]. This is particularly relevant for implementation studies where it is important to estimate the costs and impact for programmes and approaches that are often delivered by teaching staff in sub-optimal conditions (for example, without specialist set-up training and ongoing implementation support from experts). Providing this information would greatly improve the utility of research findings for decisionmakers.

8. Limitations

McMillan, Venable and Varier [82] have discussed the difficulty of establishing causality within formative assessment research. Given the difficulties in accounting for confounding variables that exist in research in applied settings, this limitation applies to the current study. There are a small number of cases per comparison group alongside some imbalance in the number of learners in the intervention and matched control groups [83,84]. The groups were also not randomly allocated, and any differences between the groups could be due to confounding factors. These features limit the trustworthiness of the findings. Learner outcomes were anonymised at class level, and this prevented more sophisticated statistical analysis. It was not possible to exclude the possibility that schools in the control group may have been utilising the formative assessment strategies contained within the FAIP training. Additionally, the study did not collect information on implementation fidelity, so it was possible that there was variation in the frequency and quality of teachers’ use of the formative assessment strategies (see [29]). The duration of the FAIP intervention in this study was relatively short, and group level, universal interventions such as this can take longer than one academic year for population impacts to develop [85].

Also, caution should be taken when considering the cost of implementing FAIP in other settings and contexts as the costs presented here may differ from those in other regions of the UK and/or other education jurisdictions.

9. Conclusions

This paper explores the utility of using economic methods to improve the quality of evaluation of a regional school improvement programme. We applied an economic analysis of educational interventions (EAEI) approach to understand the impact and cost of a formative assessment implementation project (FAIP), a regional school improvement initiative designed to improve the quality of teaching in 193 primary schools in North Wales. EAEI requires a more sophisticated consideration of costs, one that uses economic analysis techniques rather than the ‘back of envelope’ estimates commonly used in educational research [9]. This study used a quasi-experimental design to compare the effect of FAIP between the project schools and a comparison group of matched control schools, as well as considering the views of teachers and learners on the impact of FAIP in school.

The study’s findings show that FAIP helped improve teachers’ skills and learners’ independence. There was also a positive, medium effect on learners’ English reading skills. The per-pupil cost of FAIP was GBP 72.34 and the programme can be considered a low-cost, promising intervention that could be scaled up [9]. FAIP costs and impact also compare favourably with other medium- to large-scale education programmes that have been evaluated. Additionally, while the costs analysed in this study were incurred in the first year of implementation, there is the potential for programme benefits to be retained over multiple years to provide longer term impact and improved value for money. The consideration of this discounted rate effect should be a priority within all future evaluation studies.

This study has also shown that it is possible to use a CCA approach to gather important information on the costs associated with the delivery of a large, multi-site intervention. However, we have highlighted the challenge of establishing the cost of a teacher’s time and associated BAU costs. While we attempted to calculate BAU costs, there remains little standardisation around this important aspect of education economics. This is an important aspect for future research, as the need to identify core costs is central to the development of a more sophisticated approach to the use of economic methods in education. Collecting the opportunity cost of the teachers’ and/or teaching staff’s time to deliver an intervention should be routinely included in economic evaluations, but there are currently very few examples in which more sophisticated methods have been used in education research (other than the use of basic hourly, or day-rate calculations based on a teacher’s income). Also, the true cost of an educator’s time should reflect more than simply salary costs, and should include on-costs and overheads [12,86].

Considerations around the nature of outcome indicators should also be more routinely incorporated into evaluation designs so that decisionmakers can compare programmes against a standard measure. While creating an education QALY may be the answer, this is likely to present a significant challenge. Although some work has already been undertaken to transfer the concept of a QALY to crime research [87], there has been little progress made in education other than some work on health-focused interventions. The development of an education QALY is an important concept that should be a focus for future research. We recommend that an EAEI approach be routinely incorporated into programme evaluations to improve the utility of research outputs and to help policymakers and school leaders make better use of scarce resources to improve outcomes for learners.

Author Contributions

J.C.H., R.C.W. and E.T. designed and managed the study. E.T. was responsible for trial management. E.T., C.S., A.G. and F.S. contributed to data analysis. All authors made a contribution to the interpretation of the study findings and/or writing and editing the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Knowledge Economy Skills Scholarship (KESS), Wales (grant number is 80815). https://kess2.ac.uk/ (30 April 2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was granted from Bangor University Psychology Ethics and Research Committee (application number 2018-16324-A14505, approved on 25/05/18).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, E.T., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the schools, teachers, and children who participated in this study. Funding for this research was provided through a Knowledge Economy Skills Scholarship (KESS) at Bangor University. The North Wales Regional School Improvement Service (GwE) provided information on programme costs.

Conflicts of Interest

R.C.W. works for the North Wales Regional School Improvement Service (GwE). R.C.W. did not undertake any data collection or participate in any of the training sessions.

References

- Gorard, S.; See, B.H.; Siddiqui, N. What is the evidence on the best way to get evidence into use in education? Rev. Educ. 2020, 8, 570–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Value for Money in School Education: Smart Investments, Quality Outcomes, Equal Opportunities; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegram, J.; Watkins, R.C.; Hoerger, M.; Hughes, J.C. Assessing the range and evidence-base of interventions in a cluster of schools. Rev. Educ. 2022, 10, e3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R.E. How evidence-based reform will transform research and practice in education. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 55, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, H. Waiting for Godot: Cost-effectiveness analysis in education. New Dir. Eval. 2001, 2001, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, K.L.; Watkins, R.C.; Hughes, J.C. From evidence-informed to evidence-based: An evidence building framework for education. Rev. Educ. 2022, 10, e3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel-Rossi, B.; Ashdown, J. The state of cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses in education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2002, 72, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machin, S.; Mcnally, S.; Wyness, G. Educational Research Educational attainment across the UK nations: Performance, inequality and evidence Educational attainment across the UK nations: Performance, inequality and evidence. Educ. Res. 2013, 55, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M.A. Interpreting Effect Sizes of Education Interventions. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]