Abstract

The present study aimed to investigate and problematize an attractive school-age educare (SAEC) from the children’s perspectives. Which different aspects of quality appear in the children’s narratives about the SAEC activities? This was achieved by listening to children’s narratives and their voices. Forty-three children aged 6 to 10 participated in group conversations with the staff in their SAEC center. The study is theoretically based on a childhood sociological lens where children are recognized as active participants and agents for change and therefore important to listen to. The results show that an attractive School-Age Educare requires committed staff who inspire new discoveries, its own identity-specific premises with appropriate materials, the provision of planned and guided activities, the offering of unexpected and non-routine activities, and space for children’s agency to influence and to choose and to direct one’s own time. It is shown that free choices can both expand and limit children’s agency. In addition, the study illustrates how conversations with children can form a basic method for both developing quality and making the contextual factors for children’s agency visible.

1. Introduction

The Swedish school-age educare (SAEC) is internationally unique, since it combines teaching, learning, meaningful leisure time, and recreation. All 6- to 12-year-old children in need of before and after school care because their parents are working or studying are offered a place in the SAEC. The SAEC is a pedagogical arena with more children enrolled than the secondary school. Eighty-four per cent of 6- to 9-year-olds attend the SAEC before and after school and on school vacation days, and the number of enrolled children is increasing steadily [1].

The Swedish SAEC has an explicit emphasis on complementing the school, and it is integrated with primary school within the same premises, sometimes sharing material and teachers [2,3]. Its mission, to stimulate children’s learning and development, is regulated by the Education Act. The SAEC teaching should focus on offering meaningful activities and recreation before and after school and on school vacation days, in addition to promoting play and creative work in formal and informal learning situations [1]. To become a certified SAEC teacher, one needs to complete a three-year specialization in the teacher education program at university level. In addition, other occupational groups, such as child carers, are employed at the SAEC. The majority of children attend the SAEC during several of their first years in school [2].

Hence, the Swedish SAEC, and its close collaboration with the compulsory school, differs from other countries’ after-school care. In common to all is that SAEC has become an important socialization environment throughout Europe, Australia, and the United States for a rapidly growing number of children [4,5]. Historically, after-school care has been regarded as a service for parents rather than an opportunity for children to learn and develop [6]. However, programs in the United States have evolved from safe havens, especially in unsafe neighborhoods, into ambitious after-school programs promoting positive youth social, cultural, artistic, and character development [7,8]. After-school care in different countries is also organized and controlled differently (for example, by the municipality, by the church, or in a community center) which also frames the core of the activities to be conducted [9].

In Sweden, the SAEC is run by the Ministry for Education. As in the US, the teachers in the Swedish SAEC have a mission to teach, that is, to stimulate children’s learning and development. There are, however, challenges and differences in how the task of combining teaching, meaningful leisure time, and recreation is interpreted and implemented in the activities, and what is prioritized—teaching and learning or rest and recreation.

In order for the children (and the parents) to want to stay enrolled in the SAEC, a certain quality must be maintained in the program, which needs to be attractive enough for children to want to participate in it. However, the SAEC has a relatively short history and quality goals or clear methods for the teaching or evaluating the practice have not yet crystallized. What constitutes quality and attractiveness likely depends on whose perspective is being viewed, the teachers’ or the children’s. The quality of the educare center is also related to the local conditions and circumstances [10,11].

Little is known about children’s perspectives on SAEC quality and its attractiveness. By listening to the children and their perspectives when evaluating the activities, an important basis for quality development can be created. Therefore, the purpose of the study is to investigate and problematize an attractive educare program from the children’s perspectives. The study was carried out together with a municipality within the framework of an ongoing research and development project, called ULF (Utbildning/Education, Lärande/Learning, and Forskning/Research, a national governmental investment which aims to develop and test sustainable, long-term collaboration models between higher education institutions and schools in terms of research, school activities, and teacher education). At the outset, this partnering municipality presented three development areas for the project to address: creating enhanced experiences of meaningful leisure time, increasing attendance at the SAEC (particularly in grades 4 to 6), and ultimately also contributing to pupils’ achievement of the learning goals for compulsory school, as stated in the curricula. The basis for this project lay in the challenges that the partnering municipality faced, such as the pupils were leaving the SAEC at increasingly younger ages. The rationale behind the project was to develop more carefully considered and varied teaching situations in the SAEC activities, which could lead to pupils experiencing more meaningful leisure time. A more worthwhile leisure time was likely to get the pupils to stay longer during the day and attend until an older age. Increased participation in the SAEC activities could also contribute to the pupils’ own development and learning in the long run.

Previous Research

What is quality in the SAEC? Everyone can probably agree that educational activities should maintain high quality. However, there are different opinions about what the concept of quality refers to and where the limit for an acceptable standard should be set. Quality is always associated with a particular situation, a particular time period, and a particular social and cultural context, which means that quality is constantly negotiated and renegotiated. Therefore, quality cannot be measured by selecting and quantifying certain defined aspects [12]. In addition, for example in preschool, quality cannot be scrutinized the same way as quality in the SAEC.

It is also difficult to identify how to visualize quality and how it is created in educational practice. According to Sheridan and Pramling Samuelsson [13], pedagogical quality does not exist in itself; it is developed and created in the interaction between teacher and child and between child and environment. Sheridan [14] identifies four dimensions of pedagogical quality focusing on children’s opportunities for learning and development in preschool. The four dimensions are those of the child, the society, the teacher, and the learning context. This complexity of pedagogical quality is constituted in the interaction between various dimensions and aspects of human and material resources. At the same time, research on quality in the SAEC is sparse. By the turn of the century, various researchers emphasized that after-school care requires its own approach to quality standards [8,15,16,17,18] and how these standards are met. There is a lack of research focusing on the pedagogical quality of after-school care, which is remarkable considering the large number of children attending after-school care [19].

If one wants to increase the quality of an educare program, examining children’s perspectives on the activities is a good place to start [6,20,21,22]. According to Lago and Elvstrand [23], the concept of meaningful leisure time can be problematized in many ways, and one is considering for whom the program should be meaningful. If leisure time is to be meaningful, based on the SAEC or society offering enhanced value-adding activities from their perspectives [23], then the result is often that the activities are planned according to what SAEC teachers consider to be a qualitatively good program. However, teachers’ perspectives may differ from what the children want to do with their leisure time, and this is where tensions may arise. This strain is identified in Lager and Gustafsson Nyckel’s [22] study, which shows that children’s perceptions of meaningful leisure time are based on active participation and shared planning, as well as being able to decide for themselves whether or not they have to participate in group activities that are offered. Children want to be with their friends, and instead of groups and organized activities, they want free play. This confirms results from previous studies which also show that voluntariness is central from a child’s perspectives [24,25]. Other studies [6,26] report the opposite; the more the activity is structured and teacher-organized, the more frequently the children choose to participate. One study by Simoncini [6] reports that more than half of the children (52%) state that the best thing about after-school care is activities planned by the staff. They see the SAEC as an important place for play, making friends, and participating in organized activities.

Thus, structured programs in SAEC have demonstrated themselves to be able to influence children’s opportunities to experience meaningful leisure time [10,22,24] and also children’s agency. Lager [10] discusses children’s different degrees of agency based on three identified types of spaces for children in the SAEC; the Abandoned space, the Activity-based space, and the Community space. In these different spaces, the view of children is different, which consequently also means that the children’s opportunities to experience meaningful leisure time are different. The Abandoned space is characterized by children being left to themselves with few affordances from the SAEC teachers. There is a lack of staff who are knowledgeable about the SAEC mission and the ability to build on pupils’ interests, and if the staff try to carry out activities, they do not succeed in inspiring the pupils to participate. The Activity space is characterized by teacher-led activities in line with curriculum content on a dedicated timeslot each day. When all staff are present, many activities take place, which are expected to stimulate the pupils’ development and learning in accordance with the aims and objectives of the curriculum. A drawback, however, is that the activities are carried out as separate and often without a meaningful context. The Community space is characterized by children as active actors in co-constructing content, activities, and routines together with the staff. Children can choose whether they want to participate or not. More specifically, involving the children in the planning can make the most of their interests, creativity, and wishes, and in this way, children are given the opportunity for joint decision-making and can develop an understanding of democratic ways of working [27]. In the three different types of spaces, Lager [10] also describes five main aspects for achieving quality in the activities: certified teachers, functioning work teams, rooms specifically intended for SAEC instruction, available materials, and time for planning and preparation. All these aspects of quality can be expected to be found in an optimum SAEC.

Previous research identifies a balance between freedom and control. The activities of the SAEC must offer recreation and rest as well as free choices, but at the same time the activities must challenge the pupils and stimulate them to new experiences. Thus, both pedagogical teaching skills and an inviting environment are required [28]. Several studies show advantages with an increased control of the SAEC activities [26,29]. Ludvigsson and Falkner’s study [29] shows that organizing activities in large groups of children can promote creating tasks that feel comfortable. When teachers decide which pupils will play together and where and what they will play, then there are routines and organization, and the pupils can get to know new friends. Sometimes freedom can have a downside. Too much free time can contribute to vulnerable pupils becoming even more vulnerable, if teachers are rarely present in pupils’ free activities [25,30]. Thus, free time can appear problematic, as it not only gives space for pupils’ own agency, but also presents the risk of children being excluded and becoming invisible.

The purpose of the study is to investigate and problematize attractive SAEC activities from the children’s perspectives. The research question that guides the study is: What different aspects of quality appear in the children’s stories about the SAEC activities?

2. Childhood Sociology Methodological Foundation

The study is conducted on a methodological foundation of childhood sociology. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child [31] has been of great importance for the childhood research view of childhood. In the Convention on the Rights of the Child, children are established as subjects with their own rights, which means that the children’s best interests are put on the agenda [32]. Therefore, important starting points for childhood sociological research depart from a basis such as the children’s perspectives, children’s voices, agency, and rights [33]. Children have long been regarded as powerless and undeveloped in relation to fully developed adults [34], but with the Convention on the Rights of the Child [31], there is the view that children are actors with their own terms, and they have the right to be treated with respect. Within the sociology of childhood, both children and adults are regarded as active individuals and as citizens of society on equal terms [32]. Children are portrayed as bright and competent, instead of vulnerable and lacking [35], though they still have a lot to learn about the world and are therefore at the same time in need of adults’ help [33].

Children are considered active agents in the creation of their own childhood, and today, they are expected from an early age to act as competent, participating, informed, and responsible citizens of society in many different contexts [35,36]. Thus, agency [37] becomes an important concept within this perspective and can be described as children’s actions in relation to and in interaction with adults in everyday situations. Agency is a central term in sociological research, and it refers to children’s room for action and their opportunities to act independently based on their choices [38,39].

Within this paradigm, children are regarded as a unique and separate group in an adult-dominated society, within which children’s rights need to be safeguarded [40]. As a theoretical concept, agency becomes critical when childhood is seen as a social construction, which in turn emphasizes the importance of giving children and young people space [41,42]. The teachers’ task is to organize educational activities so that children are provided the conditions to develop into active participants and citizens of society. Children’s thoughts and opinions need to be considered so that they can make choices based on their own terms and conditions [43]. Teachers must therefore make opportunities available to the children to experience different occasions where they are given control over the situation [44], because children need adults to be able to develop their agency. In an educational program, which is governed by state goals, there is always a risk that teachers put themselves at the center and lead children towards goals rather than towards the children’s wishes and needs. A skillful educator instead works eclectically [45], combining different ideas into a common basis so that children’s agency does not end up on the sidelines. Children need to experience both respect and capacity to act, while simultaneously having the right to support and care. To be able to manage this balance, adults must listen to children and try to get closer to their perspectives [46]. “Listening” is not just hearing the children; in order to be able to get closer to the children’s perspectives, it is necessary for adults to listen actively to the children and also include the children’s thoughts, opinions, and suggestions in the activities [47].

Our interpretation of getting closer to the children’s perspectives is based on Johansson’s [48] definition; to start from the conditions of how children live and what these mean for the children, and based on these conditions, try to understand children’s intentions and what children express. Being able to get closer to children’s perspectives and make children important informants, is the methodological foundation of this study. This requires specific approaches as well as specific knowledge, which are described below.

3. Materials and Methods

Based on the methodological starting points described above, the focus in the present study is on children’s perspectives and their voices. The children are recognized as “agents for change”, i.e., as active participants in the daily activities [44], and it is therefore important to listen to what they have to say. Here, the children are regarded as experts in their own lives, where their different narratives together contribute images of children’s worlds, both individually and collectively [49], and in the present case, the children’s experiences of their SAEC program.

Knowledge of children and how to talk to them is important for the research process [48]. In order to hold conversations with children where they feel safe and at ease, we therefore let the SAEC teachers talk with ”their children” at their respective SAEC, because the teachers were known adults who already had a relationship with the children. The researchers and teachers together designed a questionnaire to use as a common guide for the children’s conversations. The questions (19 items) were formulated based on the teacher’s current development project on quality in their SAEC centers and focused on the children’s perspectives on the content of the educare program, as well as the premises and teachers, and the children’s thoughts on what can be changed based on their needs and interests. The staff talked with the children in small groups, so that the children could discuss different interpretations and give different expressions for how they perceive their SAEC program [50,51]. Each conversation lasted approximately 20 to 30 min, and 43 children aged 6 to 10, divided into 11 groups, participated in the conversations.

Consent from the children and their parents is required in order to be able to use the conversations for research purposes. In accordance with research ethics guidelines [52], all the guardians received written information about the purpose and methods of the study and how the data would be used and stored. They subsequently gave written consent to their child’s participation in the study. Even with their guardians’ consent, the children could decline participating in the conversations.

The implementation of the study, with the staff conducting the conversations with the children, is fully in line with the intentions behind the government’s ULF initiative, where teachers, with the support of researchers, are expected to be agents of change in their educational programs. The conversations became a way for the teachers to get closer to children’s perspectives, while at the same time, they could directly evaluate their activities and continue developing their program based on what the children said. The teachers recorded the children’s conversations on tablets, and after carrying them out, they transcribed the conversations (a total of 33 A4 pages, ca. three pages/group). The transcriptions were anonymized, before being given to the researchers; thus, the researchers do not know which child has said what or from which educare center each conversation is coming.

Analysis Process

The analysis process was based on various aspects of the concept of quality. In the context of education, there are often three different forms of quality that are scrutinized: structure, process, and result [13]. Structural quality describes the external conditions of the program, i.e., the resources the program has at its disposal and how the program is organized [53]. Structural aspects of quality thus include, for example, premises, time, staff ratio, children group size, staff qualifications, etc. Process quality involves the aspects of inner work routines of the education program, such as teacher attitudes, instruction, work methods, and the interaction between staff and children. Result quality is about what one wants to achieve with the educational methods, namely, what the children are expected to develop and learn and what new knowledge they have gained through their participation in the activities [53]. In the present study, we use structure quality and process quality in the analysis, as the questions asked to the children did not consider knowledge, learning, or teaching.

As in the present project, if one wants to influence the children to want to stay longer at the SAEC center, then the program must be attractive. The canoe model [54] offers an analysis model that connects quality with the concept of attractiveness (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Canoe model.

The model is based on the idea that necessary quality meets basic needs, expected quality meets stated needs, and attractive quality meets unconscious needs. When quality only satisfies basic needs, it is difficult to create appeal, regardless of how well the need is fulfilled [54]. The afternoon routine at the SAEC center can be taken as an example of applying necessary quality. Both parents and children assume that staff will greet the children when they arrive and that the children will receive a snack. Thus, necessary quality can be said to stand for an unspoken need [54], something obvious that is only there. Necessary quality becomes an issue only when its reliability or quality notably decreases.

Expected quality is about what one can expect, for example, what is advertised in SAEC weekly letters and what activities SAEC centers are expected to carry out based on the vocational area. Stated needs can be discussed here [54]. If the SAEC markets itself as a movement and health-inspired program, then there is the expectation there will be frequent activities involving movement in the program.

On the other hand, quality that responds to the individual’s unconscious needs does not require the same level of reliability. Bergman and Klevsjö [54] take as an example the first camera in a cell phone. The camera was of poor quality compared to a system camera, but still created appeal among customers as they had not expected a camera in their cell phone. Attractive quality is identified here. Since attractiveness lies in an unspoken and unconscious need, it is challenging to develop a program based on attractive quality. One must identify activities that provide added value and create feelings of joy, surprise, and attraction. Put simply, it means that one must create a feeling of “WOW!” instead of “okay” [54].

The present analysis of the children’s narratives and perspectives adopts a combination of these analysis concepts: structure quality, process quality, and perspectives of attractiveness. The empirical material has undergone a qualitative content analysis [55] using a deductive approach. First, all the transcriptions are read. Then, the children’s statements and formulations that convey their expression of the quality of the SAEC are marked and deductively traced and matched to structure quality and process quality [53] and the canoe model’s [54] multidimensional perspective on attractiveness. The statements and formulations in the empirical material that can be traced to what appears to be significant for the children to experience the activities as attractive were identified. Three themes emerged which also highlight structure quality and process quality: the SAEC needs a place, the SAEC needs committed staff, and the SAEC needs to contain the unexpected. The analysis involved distinguishing both similarities and differences within and between children’s narratives and perspectives. The findings are described below.

4. Results

The following sections present the themes that emerged in the analysis (T = Teacher, C = Children):

4.1. The School-Age Educare Needs a Place

The children talk very little about the SAEC as a place. When they are prompted to describe the best place at the SAEC, their descriptions are about structural quality aspects [13]:

T: What is the best place for leisure time?

C: I think a little differently, but if I have to be completely 100%, I probably actually like the climbing wall.

C: I like to swing with my friends.

C: You know, where we have our recess activities [outside].

T: Some special rooms perhaps?

C: Does the gymnasium count as a room?

C: On the grass, because there you can practice gymnastics with your friends.

C: Outside is the best place.

The fact that the children above all describe how they stay outside or in other places (the gymnasium, the climbing wall, the grass...) rather than specifically in the SAEC premises is something that recurs in the conversations with children. It also seems to be difficult for the children to identify the SAEC as a place; this becomes apparent when the teacher tries to clarify by asking, “Some particular rooms perhaps?” The fact that the SAEC staff borrow other premises (for example, classrooms and gymnasiums) shows up in the children’s answers when they describe that they lack rooms that are only for SAEC activities:

T: Is there any material or room/environment that you miss during your leisure time?

C: A computer room!

C: A playroom!

C: … that we get rooms that we can stay in that are only rooms for leisure time. And even more toys and more games that you can play on the TV (Smartboard).

Because the SAEC does not have its own rooms for activities may explain why the children do not talk very much about their indoor activities. They seem to lack places and rooms with clear identities, such as rooms for digital games and play activities.

The fact that the SAEC does not have its own premises and that the material available is not of high quality may indicate that the program is not really prioritized to take place in the schools. Such conditions affect what program can be carried out as well as how much and what kinds of material it is possible to have on hand:

C: It’s fun to draw and stuff, and I draw quite a lot, but we need to get better pens, more erasers, more pens, pencil sharpeners, and more rulers.

C: I also think it’s fun to draw, but we need to buy more markers, because many are very bad and there aren’t very many of each color.

C: Soccer goals, they are so broken. And the sand toys, they’re broken.

C: Many more soccer balls, because the ones we have are worn out, and I want better ones that are not flat.

It is evident that the premises and materials are important to the children when two older children talk about the SAEC program:

C: We wanted our own playground with only fourth and fifth graders and our own adults and premises.

C: [It was] good to split the younger kids’ leisure time and the older kids’ leisure time, so you didn’t have to be with the little ones.

C: Playing with the toddlers is not fun.

In the conversations above, the children highlight structural aspects [13] of the educare program. Analysis suggests that premises adapted to the SAEC activities, so that the SAEC also becomes a place, can make up part of necessary quality [54]. This is to say that the SAEC having its own place to be constitutes a basic need for this education program.

The children also express aspects of expected quality [54]. They expect there to be materials that are good and functional, and having these could lead to higher attractiveness. Another dimension lies in what the children say is the difficulty in performing to their full potential when material is missing or is of low quality.

Having age-appropriate activities, as well as premises and staff that are specific for the SAEC, could contribute to a clearer identity for the program. Then it is likely that the children would experience the program as both more visible and attractive. One conclusion is that if one wants to get the children to stay longer at the SAEC, then a key component is for the program to have its own premises for activities.

4.2. The School-Age Educare Needs Committed Staff

The process aspects that appear in the children’s descriptions address the inner workings of the educational activities, such as teacher attitudes, work methods, and the interaction between staff and children [13]. Often these aspects can be related to each other. An additional finding is that attractiveness in the children’s stories is about the relationship between free and scheduled time, as illustrated in the following.

According to the children, an attractive SAEC program requires committed staff who plan and organize the content of activities. In the conversations, it appears that the children appreciate the teachers offering activities that are designed and directed:

C: I like all the fun activities that the adults initiate.

C: …and that there are different activities so that there is a little bit of everything possible you can do.

As examples of things to do, the children mention both activities that the staff organize and offer and activities that the children themselves participate in and influence:

C: When we made broomstick horses.

C: Games decided by the adults.

C: When we got to make our own obstacle courses.

C: Our cycling outings to the mountain bike course.

C: Our mini-game tournaments!

It seems that a variety of games and activities planned and organized by the teachers add to making time spent at the SAEC attractive to the children, either because the children like that the adults “get the children started” or because the children simply want the adults to be involved in the activities and do things together with them. In the conversations, the children’s appreciation emerges partly because adults initiate activities, and partly because there is a range of activities, like a smorgasbord, to choose from:

C: It’s fun at leisure time if you have an activity, because then you get to do more things.

C: Yes, then you get to do a little what you want.

C: I also think it’s fun when there are activities. Then you can take the opportunity to do it, because there are always days when there are no activities.

C: [I like] the drop-in gym, because you can decide for yourself if you want to join.

C: That you can choose freely, do more difficult things, and adapt outings and activities.

What these children seem to be pointing out is that activities are not always offered, but when they are offered, the children want to take advantage of them and participate. Here, having the choice seems to be the key to attractiveness—the teachers offer a planned and guided activity and the children can choose whether they want to participate or not.

Several of the children also highlight self-initiated activities as attractive. What appears to be critical in the analysis is the possibility to choose freely or to participate in teacher-led activities. Children who emphasize having self-initiated activities seem to have some thought behind choosing to have this free time; they seem to fill it with content and have an idea of which friends to share that time with:

C: I think it’s a lot of fun hanging out with friends, because that way you can find things to do.

C: …to play soccer and be with friends.

C: …playing on the swings with [my two friends], because it’s fun to do things with them. Because they’re my best friends and it’s fun to swing.

Thus, there seem to be certain requirements when children choose a self-initiated activity over the teacher-organized activity. For the children to perceive the leisure time as attractive, the children must have ideas about what they want to do, and they must have friends to do it with. If these are missing, for example, there are no friends to share the time with, then it appears that a self-initiated activity is not something that attracts children:

C: On Thursdays we always had “your own choice”. Then you had nothing to do, but it’s more fun when you [teachers] get some games started.

C: It doesn’t seem to work to be outdoors, if you have nothing to do.

C: [I wished] we did more, because sometimes it was just that you had to be outside.

C: Because sometimes you would have this “free stuff”, and then you would just sit and paint and had nothing to do.

In these conversations, the children emphasize the importance of having variation in games and activities planned and organized by the staff. Here, process aspects [13] of the program are highlighted. One result from the analysis is that teachers who meet basic needs, for example, by offering “your own choice”, being outdoors, or “free stuff”, can contribute to necessary quality [54]. Some children are happy with this, but this does not seem to be attractive to everyone. It is boring “when you have nothing to do,” say the children. Certain prerequisite conditions seem to be required, for example, children having ideas about what to do and having friends, in order for the children’s own choice to work and be perceived as attractive.

Many of the children rather express expectations that the staff and the SAEC should help make the time at the program attractive. It also appears that children appreciate being able to participate and influence the program. One finding is that committed staff constitute a significant component of expected quality [54] as they fulfil the children’s expressed need for there to be a “smorgasbord” of activities to choose from. The children’s stories show that they want dedicated staff who inspire, guide, and motivate them to new discoveries. That there is a freedom of choice attracts the children, and here is children’s expressed desire for agency [37] and the feeling of being able to decide for themselves but based on a structured plan with the support of engaged teachers. Choosing to participate in controlled activities or choosing among free activities appears to be central to attractiveness.

4.3. The School-Age Educare Needs to Encompass the Unexpected

In the children’s responses, what appears attractive seems to be activities that the children do not expect and that differ from the everyday routine. This result relates to Bergman and Klevsjö’s [54] concept of attractiveness, where attractive quality revolves around activities that provide extra value and create feelings of joy, that is, a program that provides opportunities for the children to be surprised. The children talk about occasions during leisure time that have been extra fun:

C: I liked barbecue Fridays and when we took the ferry over to the island.

C: I think it’s fun when we have snack time outside. We usually get waffles sometimes. On Valentine’s Day we get to do things. Sometimes we get chocolate brownies.

C: When everyone brings bikes and we ride down to a beach like we did last year.

C: A video-game tournament with Super Mario, we’ve had that. But we can have more, like Lego Masters.

Thus, children talk about outings where they leave the school premises, and also about smaller activities that break with the usual routine, such as grilling hamburgers over an open fire in the school yard. Breaking the everyday routine turns out to be attractive to the children. The children’s suggestions are not “unreasonable” in relation to program resources and possibilities. On the other hand, these ideas are expressions of the fact that the unexpected, the “WOW!” experience, can be perceived as attractive.

Many of the children’s wishes are actually about process factors [13], for example, committed staff who organize activities that facilitate new discoveries. This is demonstrated when the children talk about what they would like to do during leisure time:

C: Water fights.

C: Have a soccer tournament!

C: We should have popcorn and ice cream and watch a movie.

C: You can ask a soccer team or an indoor hockey team to be able to come here. So that you can practice different sports.

Other wishes require further resources, because the children want to leave the SAEC:

C: I wish we had gone to more things. That we did a little more sometimes.

C: Take a bus to the zoo.

C: Take a bus to the swimming pool.

One can see that the activities the children describe do not commonly happen in this particular SAEC. At the same time, these are not unreasonable wishes that the children have. Activities that the children do not expect and that break from the everyday routine appear as attractive based on process quality aspects [13]. The children describe times at the SAEC that they have experienced as extra fun, such as outings when they left the school area or activities with slight changes to the daily routine. According to the analysis, these types of activities make up part of attractive quality [54], because they provide extra value and create feelings of joy, surprise, and attraction.

5. Discussion

This study starts with the children’s voices, with particular focus on various aspects of quality, in order to gain important knowledge about children’s experiences of an attractive SAEC program. With the children’s perspectives being closely adopted [48], the children have become important informants in the investigation and problematization of an attractive educare program. The results show that adapted and appropriate premises and functional material are important structural aspects of quality, and that committed staff and structured activities are important process aspects of quality.

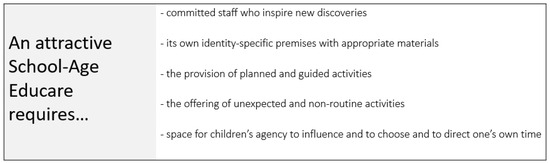

Previous research emphasizes that children generally expect the SAEC to be a place for self-initiated activities and free play [25]. The present results show a somewhat different picture. Based on what the children say in this study, there are aspects that seem to be required of SAEC activities in order for them to be perceived as attractive and thus meaningful to children. These aspects are summarized in Figure 2 and discussed below.

Figure 2.

Summary of results: aspects required in an attractive SAEC program.

An attractive [54] SAEC program seems to include committed staff who plan and organize the content of activities, as well as space for children’s agency concerning participation. It appears to be central that the children themselves can decide whether or not they want to participate. This points to the importance of children needing adults in order to develop their agency [37]. Teachers ought to give children opportunities to experience different situations where they are given control [44]. It is important that children be provided the possibility to influence, choose, and direct their time, as well as get to decide whether to participate in teacher-organized activities that may or may not inspire them to do other things. Thus, the attractive SAEC program appears as a smorgasbord, where the pupils themselves want to be able to choose what they want to take part in and opt out of what they are not interested in. Here, the perspectives on childhood sociology and perspectives on quality can be intertwined; by making space for children’s agency and influence, there is an improvement in quality of the SAEC from the children’s perspectives.

It therefore seems that offerings and freedom of choice make the program attractive, as well as that children get the possibility to exercise their agency. Here is the importance of giving children the space and opportunities needed to decide and act independently based on their choices [38,39]; these conditions can expand children’s agency. At the same time, a challenging balancing act for the teachers is identified here, between giving the children space for their own interests and experiences of control over their free time [44] and giving the children access to and opportunities for new discoveries. The balance between free and scheduled time could be understood as the children needing the space and opportunities to decide and act independently, at the same time as they have the right to the support and care [46] of staff at the SAEC. These terms become particularly visible in the children’s accounts about the self-initiated activities, where some children need support from teachers. The importance also emerges of the SAEC staff pausing, identifying, and reflecting on what the children choose to use their leisure time for. It is reasonable to think that children who have chosen to paint are happy doing that, but it could also mean that they are offered nothing else to do, which is the case in this study. In this way, free choice could also mean limited agency [37] with reduced space for acting.

The above discussion about children’s expanded or limited agency and the opportunities to make choices is also related to children’s age. The Convention on the Rights of the Child [31] states the importance of protecting vulnerable children, but also the importance of letting children emphasize their interests through active participation [35,36]. Children are regarded as competent and independent individuals, with the right to express their own ideas; while at the same time, maturity and age impact how children can, should, and may practice their rights. The present study results identify that age does play a role in attractiveness. The older children want access to challenging and meaningful activities; they do not want to participate in a program that is adapted to younger children and their needs. Here, a risk is identified that older children at the SAEC are forgotten or are “welcome, but not expressly invited”, which previous research [56] and evaluations [57] have also noted. The older children express the importance of seeing to their needs, and clearly an age-appropriate program on separate premises and with specially appointed staff can create a program that older children find attractive and want to stay at.

With choosing to consider children as social actors, it is necessary to reflect on how and in which situations they are given the opportunity to influence and participate, and when children’s opinions actually take on significance in educational practice. This study demonstrates the possibility of intertwining the childhood sociological perspective with a quality perspective. By listening to the children and their perspectives when evaluating the activities, an important basis for quality development can be created. The study also shows how conversations with children can form a basic method for making visible the contextual conditions for children’s agency. It takes knowledgeable and interested teachers in order to be able to take in the children’s perspectives and apply their ideas to areas of pedagogical development. What the children say is important information, because they are the most central actors in the SAEC program.

6. Conclusions and Implications for Practice

The SAEC represents an important place in children’s everyday life, and at the same time, it is a mirror that reflects societal perceptions of what constitutes a good childhood [47]. What a SAEC looks like today, what activities are carried out, and whether children’s agency is expanded or limited in the program, says something about the efforts put into practice. The efforts also shine through the children’s stories. A SAEC program with its own appropriate premises, where there is place for both the children’s own activities and the teachers’ organized activities, reflects an attractive, high-quality program with a clear SAEC identity. It also reflects an education system that is willing to invest in children’s leisure time at the SAEC.

To increase the ”credibility” of the research in this study [58] we have used excerpts from the transcriptions to illustrate the empirical findings. It is important to provide clear and in-depth descriptions so that others can decide the extent to which findings from one study are generalizable to another situation. Thus, this is a small-scale study, meaning that it is not possible to make claims about generalization. Despite the limitations of the data, however, the results may have relevance for other similar contexts. As such, the study constitutes a contribution to the understanding of how quality in SAEC can be scrutinized and developed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A., M.W. and M.K.; methodology, H.A., M.W. and M.K.; validation, H.A., M.W. and M.K.; formal analysis, H.A. and M.W.; investigation, H.A., M.W. and M.K.; data curation, H.A., M.W. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A. and M.W.; writing—review and editing, H.A., M.W. and M.K.; visualization, H.A.; supervision, H.A.; project administration, H.A.; funding acquisition, H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ULF (Undervisning/Education, Lärande/Learning and Forskning/Research), a national investment which aims to develop and test sustainable, long-term collaboration models between higher education institutions and schools in terms of research, school activities, and teacher education.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical considerations stated by the Swedish Research Council regarding the requirements related to information, consent, anonymity, and the right to withdraw from the project. No sensitive personal data was collected. As such, the study did not fall within the Swedish Ethical Review Act. For detailed regulations, please refer to Guide to the Ethical Review of Research on Humans, p. 65ff, available online: https://etikprovningsmyndigheten.se/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Guide-to-the-ethical-review_webb.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the participating teachers and their students for generously letting us take part of their narratives. We are also grateful to the translator Susan Canali as well as the anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Agency for Education. Elever Och Personal i Fritidshem-Läsåret 2023/24 [Pupils and Personnel in School-Age Educare-Academic Year 2023/24]; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/fler-statistiknyheter/statistik/2024-04-03-elever-och-personal-i-fritidshemmet-lasaret-2023-24 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Ackesjö, H. Supporting Children’s Transition from Preschool to the Leisure Time Center. J. Educ. Hum. Dev. 2016, 5, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lago, L. Mellanklass Kan Man Kalla Det—Om Tid Och Meningsskapande vid Övergången Från Förskoleklass Till Årskurs Ett [You Can Call It Middle Class—About Time and Meaning-Making during the Transition from Preschool Class to First Grade]. Ph.D. Thesis, Linköpings University, Linköping, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care; OECD: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Plantenga, J.; Remery, C. Out-of-school childcare: Exploring availability and quality in EU member states. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2017, 27, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoncini, K.; Cartmel, J.; Young, A. Children’s voices in Australian school age care. Int. J. Res. Ext. Educ. 2015, 3, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.F.; Collier-Meek, M.A.; Furman, M.J. Supporting out-of-school time staff in low resource communities: A professional development approach. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 63, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, R. The promise of after-school programs for low-income children. Early Child. Res. Q. 2000, 15, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audain, I. Informal extended education in Scotland. An overview of school age childcare. Int. J. Res. Ext. Educ. 2016, 4, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lager, K. Possibilities and Impossibilities for Everyday Life: Institutional Spaces in School-Age Educare. Int. J. Res. Ext. Educ. 2020, 8, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernholm, M. Undervisning i ett fritidshem för alla? [Education in a school-age educare for all?]. Pedagog. Forsk. I Sver. 2023, 28, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, G.; Moss, P.; Pence, A. Från Kvalitet Till Meningsskapande: Postmoderna Perspektiv-Exemplet Förskolan. [From Quality to Meaning Making: Postmodern Perspectives—The Preschool Example], 3rd ed.; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, S.; Pramling Samuelsson, I. Barns Lärande: Fokus i Kvalitetsarbetet. [Children’s Learning in the Quality Work], 2nd ed.; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, S. Dimensions of pedagogical quality in preschool. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2007, 15, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, M.; Hawken, A.; Jacknowitz, A. Accountability for After-School Care; Devising Standards and Measuring Adherence to Them; RAND: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Larner, M.B.; Zippiroli, L.; Behrman, R.E. When school is out; analysis and recommendations. Future Child. 1999, 9, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scott-Little, C.; Hamann, M.S.; Jurs, S.G. Evaluations of after-school programs: A meta-evaluation of methodologies and narrative synthesis of findings. Am. J. Eval. 2002, 23, 387–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.; Barker, J. Contested spaces; children’s experiences of out of school care in England and Wales. Childhood 2000, 7, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukkink, R.; Boogaard, M. Pedagogical quality of after-school care: Relaxation and/or enrichment? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 112, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartmel, J.; Hurst, B.; Bobongie-Harris, F.; Hadley, F.; Barblett, L.; Harrison, L.; Irvine, S. Do children have a right to do nothing? Exploring the place of passive leisure in Australian school age care. Childhood 2023, 31, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, E. Teknisk, praktisk och frigörande kvalitet i fritidshemmet systematiska kvalitetsarbete. [Technical, practical and liberating quality in the school-age educare systematic quality work]. Pedagog. Forsk. I Sver. 2023, 28, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lager, K.; Gustafsson-Nyckel, J. Meaningful leisure time in school-age educare: The value of friends and collective strangers. Educ. North 2022, 29, 84–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lago, L.; Elvstrand, H. Elever på gränsen: Elevers perspektiv på att sluta i fritidshem [Pupils on the edge: Pupil’s perspectives on leaving the school-age educare]. In Barn i Fritidshem; Elvstrand, H., Lago, L., Eds.; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Elvstrand, H.; Närvänen, A.L. Children’s Own Perspectives on Participation in Leisure-time Centers in Sweden. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, L.; Elvstrand, H. Frihet, frivillighet och styrning: Elevers friutrymme i fritidshem [Freedom, voluntariness and governance: Pupils’ free space in school-age educare]. In Fritidsdidaktiska Dilemman; Lundmark, S., Kontio, J., Eds.; Natur och Kultur: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wernholm, M.; Ackesjö, H.; Gardesten, J.; Funck, U. Mjuka förmågor—Ett sätt att begreppsliggöra arbetet med “det sociala” i fritidshemmet [Soft skills—A way to conceptualize the work with “the social” in the school-age educare]. In Fritidsdidaktiska Dilemman; Lundmark, S., Kontio, J., Eds.; Natur och Kultur: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Orwehag, M. Didaktik i fritidshemmet [Didactics in school-age educare]. In Fritidshemmets Pedagogik i Ny Tid, 2nd ed.; Haglund, B., Nyckel, J.G., Lager, K., Eds.; Gleerups: Malmö, Sweden, 2020; pp. 139–170. [Google Scholar]

- National Agency for Education. Läroplan för Grundskolan, Förskoleklassen och Fritidshemmet: Lgr22 [Curriculum for Primary School, Preschool Class and School-Age Educare]; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson, A.; Falkner, C. Fritidshem—Ett gränsland i utbildningsslandskapet: Lärare i fritidshems institutionella identitet [School-age educare—A borderland in the educational landscape: Teachers in the institutional identity of school-age educare]. Nord. Tidsskr. Pedagog. Og Krit. 2019, 5, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, L.; Elvstrand, H. “Jag har oftast ingen att leka med”: Sociala exkludering på fritidshem [“Usually I have no one to play with”: Peer rejection in school-age educare]. Nord. Stud. Educ. 2019, 39, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Eilard, A. Perspektiv på barndom och barns villkor i relation till lärande [Perspectives on childhood and children’s conditions in relation to learning]. In Perspektiv på Barndom Och Barns Lärande: En Kunskapsöversikt om Lärande i Förskolan och Grundskolans Tidigare år; Åsén, G., Ed.; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010; pp. 21–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bergnehr, D. Barnperspektiv, barns perspektiv och barns aktörskap—En begreppsdiskussion [Child perspective, children’s perspectives and children’s agency—A conceptual discussion]. Nord. Tidsskr. Pedagog. Og Krit. 2019, 5, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qvortrup, J. Varieties of Childhood. In Studies in Modern Childhood. Society, Agency, Culture; Qvortrup, J., Ed.; Palgrave McMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2005; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, D. Barndomspsykologi-Utveckling i en Förändrad Värld [Childhood Psychology Development in a Changing World], 2nd ed.; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kampmann, J. Societalization of Childhood: New Opportunities? New Demands? In Beyond the Competent Child. Exploring Contemporary Childhoods in the Nordic Welfare Societies; Brembeck, H., Johansson, B., Kampmann, J., Eds.; Roskilde University Press: Roskilde, Denmark, 2004; pp. 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mayall, B. Children in action at home and school. In Children’s Childhoods Observed and Experienced; Mayall, B., Ed.; The Falmer Press: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, M. Barns och Lärares Aktiviteter med Datorplattor och Appar i Förskolan. [Children’s and Teacher’s Activities with Computer Tablets and Apps in Preschool]. Ph.D. Thesis, Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen, H.; Kumpulainen, K. A visual narrative inquiry into children’s sense of agency in preschool and first grade. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 3, 141–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, F.; Baader, M.S.; Betz, T.; Hungerland, B. Reconceptualising Agency and Childhood: New Perspectives in Childhood Studies; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge, D. The education of children in care: Agency and resilience. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 77, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdall EK, M.; Punch, S. Not so ‘New’? Looking Critically at Childhood Studies. Child. Geogr. 2012, 10, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerlöf, P.; Wallerstedt, C.; Kultti, A. Barns agency i lekresponsiv undervisning [Children’s agency in play responsive teaching]. Forsk. Om Undervis. Och Lärande 2019, 7, 44–63. [Google Scholar]

- Caiman, C.; Lundegård, J. Preschool children’s agency in learning for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiman, C. Naturvetenskap i Tillblivelse: Barns Meningsskapande Kring Biologisk Mångfald och en Hållbar Framtid [Natural Science in the Making: Children’s Sense-Making around Biological Diversity and a Sustainable Future]. PhD Thesis, Stockholms University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pramling Samuelsson, I.; Sommer, D.; Hundeide, K. Barnperspektiv och Barns Perspektiv i Teori och Praktik [Child Perspective and Children’s Perspective in Theory and Practice]; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ackesjö, H. Fritidshemmets ideologiska vändning [The school-age educare’s ideological turn]. In Barn i Fritidshem; Elvstrand, H., Lago, L., Eds.; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, E. Att närma sig barns perspektiv: Forskares och pedagogers möten med barns perspektiv. Pedagog. Forsk. I Sver. 2003, 8, 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.; Moss, P. Listening to Young Children: The Mosaic Approach; National Children’s Bureau: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aarsand, P. The ordinary player: Teenagers talk about digital games. J. Youth Stud. 2012, 15, 961–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernholm, M. Children’s Out-of-School Learning in Digital Gaming Communities. Des. Learn. 2021, 13, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Research Council. God Forskningssed [Good Research Practice]; Swedish Research Council: Sweden, Stockholm, 2017; Available online: https://www.vr.se/analys/rapporter/vara-rapporter/2017-08-29-god-forskningssed.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Asplund Carlsson, M.; Pramling Samuelsson, I.; Kärrby, G. Strukturella Faktorer och Pedagogisk Kvalitet i Barnomsorg och Skola—En Kunskapsöversikt [Structural Factors and Educational Quality in Childcare and School—A Knowledge Overview]; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2001; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.6bfaca41169863e6a6541c8/1553957357900/pdf829.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Bergman, B.; Klefsjo, B. Från Behov Till Användning [Quality. From Need to Use]; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Qualitative Content Analysis, 2nd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ackesjö, H; Dahl, M. Det Bästa med Fritids var att Kompisarna var Där. En diskussion om meningsfull fritid och hållbar fritidspedagogik [“The best thing about SAEC was that the friends were there.” A discussion about meaningful leisure time and sustainable leisure time pedagogy]. In Fritidspedagogik, Fritidshemmets Teorier och Praktiker; Klerfelt, A., Haglund, B., Eds.; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011; pp. 204–223. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish School Inspectorate. Kvalitet i Fritidshem [Quality in the School-Age Educare]; Skolinspektionen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010; Available online: https://skolinspektionen.se/globalassets/02-beslut-rapporter-stat/granskningsrapporter/tkg/2010/fritidshem/rapport-kvalitet-fritidshem.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).