Successful School Principalship: A Meta-Synthesis of 20 Years of International Case Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How was success defined?

- RQ2: What were the successful principalship practices (SPPs) across countries?

- RQ3: What are the values and qualities of successful principals in the global school context?

2. Background and Perspectives

3. Methods

3.1. Search Process, Study Screening and Selection, and Quality Assessment

- Explicitly report their data;

- Include evidence related to at least one of the study’s four research questions;

- Clearly state their aims and objectives;

- Use a research design appropriate to achieving the study’s objectives;

- Provide a clear account of how the data were collected and handled;

- Use appropriate and clearly specified analytic methods;

- Display enough data to support interpretations and conclusions.

3.2. Coding Scheme and Analytical Framework for Review

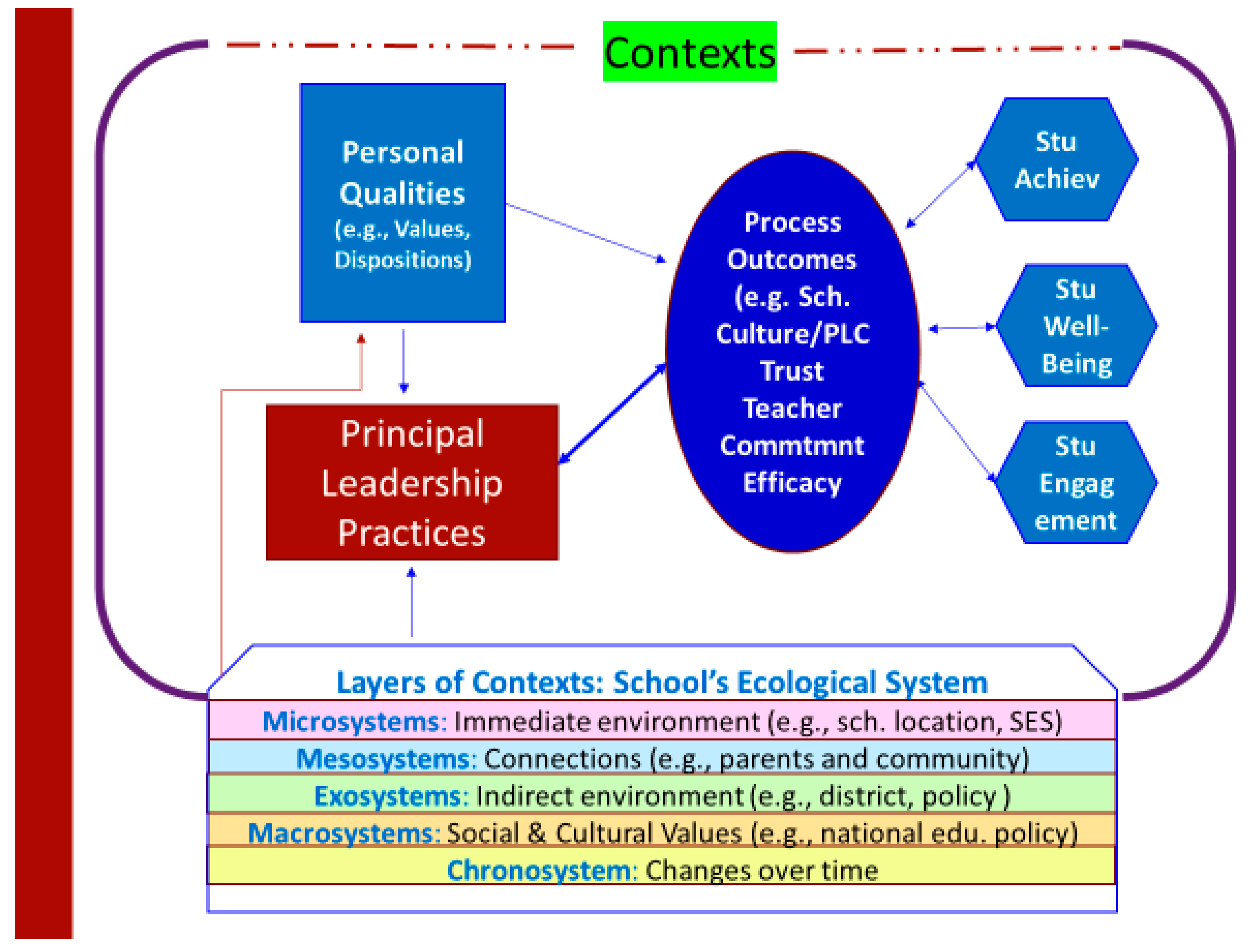

3.3. Ecological Human Systems Theory

3.4. Data Extraction and Coding

3.5. Data Analysis and Synthesis

- Reciprocal translation analysis. The researcher identifies key metaphors, themes, or concepts and translates them in relation to one another (i.e., judges the ability of the concepts of one study to capture concepts from another).

- Refutational synthesis. The researcher characterizes and attempts to explain contradictions between the separate studies.

- Line-of-argument analysis. The researcher builds a general interpretation grounded in the findings of the separate studies, identifying through constant comparison themes that are the most powerful in representing the entire dataset.

4. Findings

4.1. How Success Was Defined (RQ1)

4.2. Successful Principalship Practices (RQ2)

- Domain 1: Building shared visions, setting standards, and identifying pathways to improvement

- Identify and articulate a shared vision.

- Demonstrate and implement high expectations.

- Foster agreement about group goals and keep focused on the agreed school goals and priorities.

- Domain 2: Enhancing collective instructional competencies and capabilities

- 4.

- Build supportive, strong, and trustful working relationships inside the school community.

- 5.

- Enhance collective instructional competencies (esp. culturally responsive teaching and pedagogy).

- 6.

- Provide continuing, differentiated, and collective support for individual staff.

- 7.

- Offer intellectual stimulation that promotes reflection.

- 8.

- Model desired values and practices.

- Domain 3: Building organizational capacities and collaborative cultures

- 9.

- Restructure the organization/create structures to support, institute, and sustain collaborative processes, inquiries, and cultures, and desired practices.

- 10.

- Build collaborative, distributed leadership in the school, utilizing participatory governance and involving stakeholders in decision-making.

- 11.

- Develop a safe, orderly, inclusive, and conducive learning environment.

- Domain 4: Improving the instructional program

- 12.

- Continually improve classroom teaching and foster instructional innovation (e.g., new pedagogy).

- 13.

- Staff the school’s program with teachers well matched to the school’s priorities (e.g., hiring high-quality, diverse teachers).

- 14.

- Provide instructional support.

- 15.

- Monitor student progress.

- 16.

- Buffer staff from distractions to their work.

- 17.

- Redesign and enrich the curriculum.

- Domain 5: Building the School’s Capacity to Manage Change over Time

- 18.

- Build civic relationships with school communities and enlist greater parent and external community’s support, involvement, or partnership.

- 19.

- React to the context with contextual intelligence and be proactive (e.g., reach out to and meet the needs of the school and communities).

- 20.

- Build the school’s capacity to change with resilience.

- Build supportive, strong, and trustful working relationships inside the school community.

- Enhance teachers’ collective teaching competencies and capabilities (e.g., common teaching philosophy, consistent instructional practices, common assessment, adaptability, and knowledge accommodation).

- Respond to the context with contextual intelligence and being proactive (e.g., reach out to and meet the needs of the school and communities).

- Build the school’s capacity to manage change.

- Apply systems thinking to navigate layers of contextual influences with political acuity to solve complex problems.

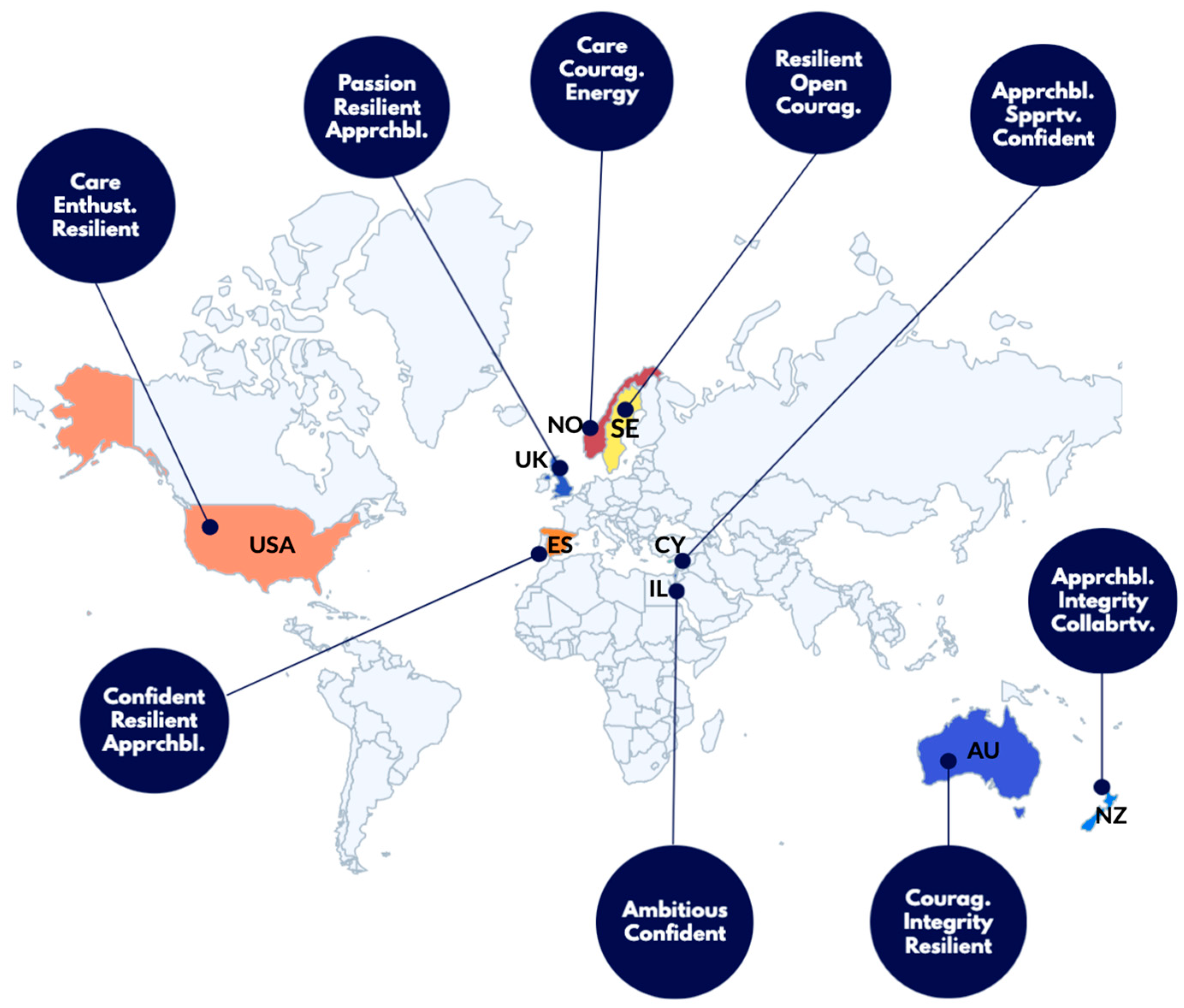

4.3. RQ3: What Are the Qualities of Successful Principals in the Global School Context?

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leithwood, K.; Louis, K.S. Linking Leadership to Student Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Sun, J.-P.; Schumacker, R. How school leadership influences student learning: A test of “the four paths model”. Educ. Adm. Q. 2020, 56, 570–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Sun, J.-P.; Pollock, K. (Eds.) How school leaders contribute to student success: The four paths. In Studies in Educational Leadership; Springer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Day, C. (Eds.) Starting with what we know. In Successful School Leadership in Times of Change: An International Perspective; Springer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, G. Does fatigue from ongoing news issues harm news media? Assessing reciprocal relationships between audience issue fatigue and news media evaluations. J. Stud. 2022, 23, 858–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulford, B.; Edmunds, B.; Ewington, J.; Kendall, L.; Kendall, D.; Silins, H. Successful school principalship in late-career. J. Educ. Adm. 2009, 47, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Gurr, D. Leading Schools Successfully: Stories from the Field; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ärlestig, H.; Day, C.; Johansson, O. International school principal research. In A Decade of Research on School Principals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ärlestig, H.; Johansson, O.; Nihlfors, E. Sweden: Swedish school leadership research—An important but neglected area. In A Decade of Research on School Principals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L. Australian and Pacific perspectives. In Successful School Leadership: International Perspectives; Pashiardis, P., Johansson, O., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2016; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Mulford, B. Leadership and organizational and student learning in Tasmanian Schools. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2008, 36, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mulford, B. Quality evidence on school leadership for Australian schools? Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2008, 36, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pashiardis, P.; Kafa, A. Successful School Principals in Primary and Secondary Education: A Comprehensive Review of a Ten-Year Research in Cyprus. J. Educ. Adm. 2022, 60, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Arcadia, C.; Nava-Lara, S.; Rodríguez-Uribe, C.; Glasserman-Morales, L.D. What we know about successful principals in Mexico. J. Educ. Adm. 2022, 60, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.L.; Day, C. The International Successful School Principalship Project (ISSPP): An overview of the project, the case studies and their contexts. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2007, 35, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.; Møller, J.; Jacobson, S.L.; Wong, K.C. Cross-national comparisons in the International Successful School Principalship Project (ISSPP): The USA, Norway and China. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2008, 52, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, L.; Bennett, J.; Murakami, E.T.; Johansson, O.; Gurr, D. Heroic leadership in Australia, Sweden, and the United States. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2014, 28, 785–797. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D. Successful school leadership across contexts and cultures. Lead. Manag. 2014, 20, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ylimaki, R.M.; Jacobson, S.; Johnson, L.; Klar, H.W.; Nino, J.; Orr, M.T.; Scribner, S. Successful principal leadership in challenging American public schools: A brief history of ISSPP research in the United States and its major findings. J. Educ. Adm. 2022, 60, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L.; Goode, H. International educational leadership projects. In Educational Leadership for Social Justice and Improving High-Needs Schools: Findings from 10 Years of International Collaboration; Barnett, B., Woods, P., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2021; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.; Leithwood, K. Successful School Leadership in Times of Change; Springer-Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ylimaki, R.M.; Jacobson, S.L. Comparative perspectives on organizational learning, instructional leadership, and culturally responsive practices: Conclusions and future directions. In US and Cross-National Policies, Practices, and Preparation; Ylimaki, R., Jacobson, S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Mulford, B. Recent developments in the field of educational leadership: The challenge of complexity. In Second International Handbook of Educational Change; Hargreaves, A., Lieberman, A., Fullan, A., Hopkins, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 23, pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, L.; Goode, H. Successful school leadership project, Morang South/school D case study. Victoria, Australia. 2004; unpublished research report. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, L.; Gurr, D. Theory and practice of successful school leadership in Australia. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2011, 31, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L.; Goode, H. Global research on principal leadership. In The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Educational Administration; Nobit, G.W., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, S.D. Schools as soft systems: Addressing the complexity of ill-defined problems. In Leading Holistically: How States, Districts, and Schools Improve Systemically; Shaked, H., Schechter, C., Daly, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, K.M.; Levitt, H.M. Heterosexism and the self: A systematic review informing LGBQ-affirmative research and psychotherapy. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2021, 33, 376–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D. Weight of evidence: A framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Res. Pap. Educ. 2007, 22, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, C.H.; Savin-Baden, M. An Introduction to Qualitative Research Synthesis: Managing the Information Explosion in Social Science Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks, C.A.; Rutakumwa, W.; O’Leary, K.A.; Profetto-McGrath, J.; Milner, M.; Levers, M.J.; Scott-Findlay, S. Sources of practice knowledge among nurses. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S. Secondary analysis in qualitative research: Issues and implications. Crit. Issues Qual. Res. Methods 1994, 1, 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Noblit, G.W.; Hare, R.D. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Major, C.H.; Savin-Baden, M. Integration of qualitative evidence: Towards construction of academic knowledge in social science and professional fields. Qual. Res. 2011, 11, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Baden, M.; Major, C.H. Using interpretative meta-ethnography to explore the relationship between innovative approaches to learning and their influence on faculty understanding of teaching. High. Educ. 2007, 54, 833–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Dimmock, C.A. School Leadership and Administration: Adopting a Cultural Perspective; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhouse, H.; Lu, C.Y.; Massaro, V.R. Multicultural education professional development: A review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2019, 89, 416–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett-Page, E.; Thomas, J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, H.M. How to conduct a qualitative meta-analysis: Tailoring methods to enhance methodological integrity. Psychother. Res. 2018, 28, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, Y.; Caskurlu, S.; Kenney, R.H.; Kozan, K.; Richardson, J.C. Moving qualitative synthesis research forward in education: A methodological systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 35, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timulak, L.; Creaner, M. Experiences of conducting qualitative meta-analysis. Couns. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 28, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S.M.; Anagnostopoulos, D. Methodological guidance paper: The craft of conducting a qualitative review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2021, 91, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 109, 174–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis-Onofre, R.; Catalá-López, F.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C. How to properly use the PRISMA Statement. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association (APA). Qualitative Meta-Analysis Article Reporting Standards Information Recommended for Inclusion in Manuscripts Reporting Qualitative Meta-Analyses. J. Artic. Report. Stand. 2018, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L. Successful school leadership: Victorian case studies. Int. J. Learn. 2003, 10, 945–957. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L.; Di Natale, E.; Ford, P.; Hardy, R.; Swann, R. Successful school leadership in Victoria: Three case studies. Lead. Manag. 2003, 9, 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, L. Making a difference. In Leading Australia’s Schools; Duignan, P., Gurr, D., Eds.; ACEL and DEST: Sydney, Australia, 2007; pp. 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D. We can be the best. In Leading Australia’s Schools; Duignan, P., Gurr, D., Eds.; ACEL and DEST: Sydney, Australia, 2007; pp. 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L.; Mulford, B. Instructional Leadership in Three Australian Schools. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2007, 35, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, L.; Goode, H.; Gurr, D. An Australian model of successful school leadership: Moving from success to sustainability. J. Educ. Adm. 2009, 47, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, J.; Mulford, B. Australian principal instructional leadership: Direct and indirect influence. Magis Rev. Int. Investig. Educ. 2010, 2, 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, L.; Goode, H.; Gurr, D. Sustaining School and Leadership Success in Two Australian Schools. In How School Principals Sustain Success over Time: International Perspectives; Moos, L., Johansson, O., Day, C., Eds.; Springer-Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, J.; Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L. The developing principal. In Leading Schools Successfully-Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, L.; Gurr, D.; Goode, H. Dare to Make a Difference: Successful Principals Who Explore the Potential of their Role. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2016, 44, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Acquaro, D. The strategic role of leadership in preventing early school leaving and failure. IPRASE J. Learn. Res. Innov. Educ. 2018, 10, 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L.; Longmuir, F.; McCrohan, K. The Leadership, Culture and Context Nexus: Lessons from the Leadership of Improving Schools. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. (Commonw. Counc. Educ. Adm. Manag. (CCEAM)) 2018, 46, 22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L.; Longmuir, F.; McCrohan, K. Successful school leadership that is culturally sensitive but not context constrained. In Leadership, Culture and School Success in High-Need Schools; Murakami, E.T., Gurr, D., Notman, R., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2019; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Longmuir, F. Resistant leadership: Countering dominant paradigms in school improvement. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 2019, 51, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurr, D.; Longmuir, F.; Reed, C. Creating successful and unique schools: Leadership, context and systems thinking perspectives. J. Educ. Adm. 2021, 59, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashiardis, P.; Savvides, V.; Lytra, E.; Angelidou, K. Successful school leadership in rural contexts: The case of Cyprus. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2011, 39, 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashiardis, P.; Kafa, A.; Marmara, C. Successful secondary principalship in Cyprus. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2012, 26, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashiardis, P.; Savvides, V. Trust in leadership: Keeping promises. In Leading Schools Successfully: Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Pashiardis, P.; Brauckmann, S.; Kafa, A. Let the context become your ally: School principalship in two cases from low performing schools in Cyprus. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2018, 38, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashiardis, P.; Brauckmann, S.; Kafa, A. Leading low performing schools in Cyprus: Finding pathways through internal and external challenges. Lead. Manag. 2018, 24, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yaakov, O.B.; Tubin, D. The Evolution of Success. In Leading Schools Successfully-Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tubin, D. School success as a process of structuration. Educ. Adm. Q. 2015, 51, 640–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notman, R. In pursuit of excellence. J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Pract. 2009, 24, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Notman, R. New Zealand—A values-led principalship: The person within the profession. In Leading Schools Successfully-Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Notman, R. Professional identity, adaptation and the self: Cases of New Zealand school principals during a time of change. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notman, R. An evolution in distributed educational leadership: From sole leader to co-principalship. J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Pract. 2020, 35, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, J.; Eggen, A.B. Team leadership in upper secondary education1. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2005, 25, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, J. Democratic schooling in Norway: Implications for leadership in practice. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2006, 5, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedøy, G.; Møller, J. Successful school leadership for diversity. Examining two contrasting examples of working for democracy in Norway. ISEA Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2007, 35, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Møller, J.; Vedøy, G.; Presthus, A.M.; Skedsmo, G. Successful principalship in Norway: Sustainable ethos and incremental changes? J. Educ. Adm. 2009, 47, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, J.; Vedøy, G.; Presthus, A.M.; Skedsmo, G. Fostering learning and sustained improvement: The influence of principalship. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2009, 8, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, J.; Vedøy, G. Norway-Leadership for social justice: Educating students as active citizens in a democratic society. In Leading Schools Successfully: Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ballangrud, B.B.; Paulsen, J.-M. Leadership Strategies in Diverse Intake Environments. Nord. J. Comp. Int. Educ. (NJCIE) 2018, 2, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, J. Creating cultures of equity and high expectations in a low-performing school. Interplay between district and school leadership. Nord. J. Comp. Int. Educ. (NJCIE) 2018, 2, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballangrud, B.O.B.; Aas, M. Ethical thinking and decision-making in the leadership of professional learning communities. Educ. Res. 2022, 64, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, C.; Martín-Romera, A.; Martínez-Valdivia, E.; Olmo-Extremera, M. Successful secondary school principalship in disadvantaged contexts from a leadership for learning perspective. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2017, 38, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Falcón, I.; García-Rodríguez, M.P.; Gómez-Hurtado, I.; Carrasco-Macías, M.J. The importance of principal leadership and context for school success: Insights from ‘(in) visible school’. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaella, C.M. A comparative study of the professional identity of two secondary school principals in disadvantaged contexts. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2020, 19, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höög, J.; Johansson, O.; Olofsson, A. Successful principalship: The Swedish case. J. Educ. Adm. 2005, 43, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ärlestig, H. Multidimensional organizational communication as a vehicle for successful schools? J. Sch. Public Relat. 2007, 28, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, O.; Davis, A.; Geijer, L. A perspective on diversity, equality and equity in Swedish schools. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2007, 27, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ärlestig, H. In school communication: Developing a pedagogically focussed school culture. Values Ethics Educ. Adm. 2008, 7, n1. [Google Scholar]

- Höög, J.; Johansson, O.; Olofsson, A. Swedish successful schools revisited. J. Educ. Adm. 2009, 47, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ärlestig, H.; Törnsén, M. Sweden–Teachers make the difference: A former principal’s retrospective. In Leading Schools Successfully-Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C. Resilient principals in challenging schools: The courage and costs of conviction. Teach. Teach. 2014, 20, 638–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C. Sustaining the turnaround: What capacity building means in practice. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2014, 12, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.; Gu, Q.; Sammons, P. The impact of leadership on student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educ. Adm. Q. 2016, 52, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Gu, Q. How Successful Secondary School Principals in England Respond to Policy Reforms: The Influence of Biography. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2018, 17, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Sammons, P.; Chen, J. How principals of successful schools enact education policy: Perceptions and accounts from senior and middle leaders. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2018, 17, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.L.; Brooks, S.; Giles, C.; Johnson, L.; Ylimaki, R. Successful school leadership in high poverty schools: An examination of three urban elementary schools. Educ. Financ. Policy 2004, 6, 291–317. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, C.; Johnson, L.A.U.R.I.; Brooks, S.; Jacobson, S.L. Building bridges, building community: Transformational leadership in a challenging urban context. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2005, 15, 519–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, C. Transformational leadership in challenging urban elementary schools: A role for parent involvement? Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2006, 5, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L. Rethinking successful school leadership in challenging US schools: Culturally responsive practices in school-community relationships. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2007, 35, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, C. Building capacity in challenging US schools: An exploration of successful leadership practice in relation to organizational learning. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2007, 35, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ylimaki, R. Instructional leadership in challenging US schools. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2007, 35, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, S.L.; Johnson, L.; Ylimaki, R.; Giles, C. Sustaining Success in an American School: A Case for Governance Change. J. Educ. Adm. 2009, 47, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, E.M.; Garza, E.; Merchant, B. Successful school leadership in socioeconomically challenging contexts: School principals creating and sustaining successful school improvement. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2010, 38, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Garza, E.; Murakami-Ramalho, E.; Merchant, B. Leadership succession and successful leadership: The case of Laura Martinez. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2011, 10, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.; Johnson, L.; Ylimaki, R. Sustaining school success: A case for governance change. In How School Principals Sustain Success over Time: International Perspectives; Moos, L., Johansson, O., Day, C., Eds.; Springe: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Dugan, T.; Ylimaki, R.; Bennett, J. Funds of Knowledge and Culturally Responsive Leadership. J. Cases Educ. Leadersh. 2012, 15, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, E.T.; Garza, E.; Merchant, B. When Hispanic Students Are Not Expected to Succeed: A Successful Principal’s Experience. J. Cases Educ. Leadersh. 2012, 15, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylimaki, R.M.; Bennett, J.V.; Fan, J.; Villasenor, E. Notions of “Success” in southern Arizona Schools: Principal leadership in changing demographic and border contexts. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2012, 11, 168–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, H.W.; Brewer, C.A. Successful leadership in high-needs schools: An examination of core leadership practices enacted in challenging contexts. Educ. Adm. Q. 2013, 49, 768–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, H.W.; Brewer, C.A.; Whitehouse, M.L. AVIDizing a high poverty middle school: The case of Magnolia Grove Middle School. Engag. Int. J. Res. Pract. Stud. Engagem. 2013, 1, 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dugan, T.; Bennett, J. USA—The story of new principals. In Leading Schools Successfully-Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- Klar, H.W.; Brewer, C.A. Successful leadership in a rural, high-poverty school: The case of County Line Middle School. J. Educ. Adm. 2014, 52, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor-Ragan, Y.; Jacobson, S. In her own words: Turning around an under-performing school. In Leading Schools Successfully: Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Gorgen, K. Successful School Leadership; Education Development Trust: Berkshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISSPP. ISSPP (International Susccessful School Principalship Project) 2022 Booklet 1; ISSPP: Tübingen, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.; Sun, J.; Grice, C. Research on successful school leadership. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th ed.; Tierney, R.J., Rizvi, F., Erkican, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.L.; Brooks, S.; Giles, C.; Johnson, L.; Ylimaki, R. Successful leadership in three high-poverty urban elementary schools. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2007, 6, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.L. Leadership for success in high poverty elementary schools. J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Pract. 2008, 23, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, P.T. In pursuit of authentic school leadership practices. In The Ethical Dimensions of School Leadership; Begley, P.T., Johansson, O., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Norwell, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tubin, D.; Pinyan-Weiss, M. Distributing positive leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2015, 43, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, L.; Johansson, O.; Day, C. How School Principals Sustain Success over Time: International Perspectives; Springer-Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.-P.; Leithwood, K. Transformational school leadership effects on student achievement. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2012, 11, 418–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K. School Leadership and Complexity Theory; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides, M. Successful school leadership in New Zealand: A scoping review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.L.; Johnson, L. Successful leadership for improved student learning in high needs schools: US perspectives from the international successful school principalship project (ISSPP). In International Handbook of Leadership for Learning; Townsend, T., MacBeath, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 553–569. [Google Scholar]

- Garza, E.; Drysdale, L.; Gurr, D.; Jacobson, S.L.; Merchant, B. Leadership for school success: Lessons from effective principals. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2014, 28, 798–811. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L.; Clarke, S.; Wildy, H. High-need schools in Australia: The leadership of two principals. Manag. Educ. 2014, 28, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, J.; Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L. The formation and practice of a successful principal: Rick Tudor, Headmaster of Trinity Grammar School, Melbourne, Australia. In Leading Schools Successfully: Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, S.L.; Johnson, L.; Ylimaki, R.; Giles, C. Successful leadership in challenging US schools: Enabling principles, enabling schools. J. Educ. Adm. 2005, 43, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbar, V.; Marshall, G.; Power, P. Better Schools, Better Teachers, Better Results: A Handbook for Improved Performance Management in your School; Acer Press: Sydney, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C. England—Identity challenge: The courage of conviction. In Leading Schools Successfully: Stories from the Field; Day, C., Gurr, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 98–114. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, J.; McEachen, J.; Fullan, M.; Gardner, M.; Drummy, M. Dive into Deep Learning: Tools for Engagement; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mulford, B.; Johns, S. Successful school principalship. Lead. Manag. 2004, 10, 45–76. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, H.; Drysdale, L.; Gurr, D. What we know about successful school leadership from Australian cases and an open systems model of school leadership. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincu, M.; Colman, A.; Day, C.; Gu, Q. Lessons from two decades of research about successful school leadership in England: A humanistic approach. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutz, M. Toward a conceptual model of contextual intelligence: A transferable leadership construct. Leadersh. Rev. 2008, 8, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P. Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubin, D. From principals’ actions to students’ outcomes: An explanatory narrative approach to successful Israeli schools. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2011, 10, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S. Leadership effects on student achievement and sustained school success. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2011, 25, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. The personal resources of successful leaders: A narrative review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Year | Pub Type | Journal Quality | Reader-Ship | Case Country | Research and Sampling Methods | Cases | Participants | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gurr and Drysdale [46] | 2003 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 3 P and 3 AP and 18 T and 48–60 Stu and 48–60 Par and 3 CC and 3 CSB and 3 SCM | 1 and 6 |

| Gurr, Drysdale, Di Natale, Ford, Hardy and Swann [47] | 2003 | 1 | 3 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 3 P and 3 AP and 18 T and 48–60 Stu. and 48–60 Par. and 3 CC and 3 CSB and 3 SCM | 1 and 6 |

| Drysdale [48] | 2007 | 2 | N/A | N/A | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and 1 AP and 6 T and 10–16 Stu. And 10–16 Par. and 1 CC and 1 CSB and 1 SCM | N/A |

| Gurr [49] | 2007 | 2 | N/A | N/A | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and 1 AP and 6 T and 10–16 Stu. and 10–16 Par. and 1 CC and 1 CSB and 1 SCM | 4 and 6 |

| Gurr, Drysdale and Mulford [50] | 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 3 P and 3 AP and 18 T and 48–60 Stu and 48–60 Par and 3 CC and 3 CSB and 3 SCM | 1 and 6 |

| Drystale, Goode and Gurr [51] | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and 1 AP and 1 CC and 6 T and 1 CSB and 1 SCM and 10–16 Par. and 10–16 Stu. | 1 and 3 |

| Gurr, Drysdale and Mulford [52] | 2010 | 1 | 3 | N/A | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 3 P and 3 AP and 18 T and 48–60 Stu and 48–60 Par and 3 CC and 3 CSB and 3 SCM | 1 and 6 |

| Drysdale, Goode and Gurr [53] | 2011 | 2 | N/A | N/A | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | 2 P and 2 AP and 12 T and 20–32 Stu. and 20–32 Par. and 2 CC and 2 CSB and 2 SCM | 1 and 3 and 6 |

| Drysdale and Gurr [25] | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 4 | 4 P and 4 AP and 24 T and 64–80 Stu and 64–80 Par and 4 CC and 4 CSB and 4 SCM | 1 and 2 |

| Doherty, Gurr, and Drysdale [54] | 2014 | 2 | N/A | N/A | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and 1 AP and 1 CC and 6 T and 1 CSB and 1 SCM and 10–16 Par. and 10–16 Stu. | N/A |

| Drystale, Gurr, and Goode [55] | 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 3 P and 3 AP and 18 T and 48–60 Stu and 48–60 Par and 3 CC and 3 CSB and 3 SCM | 1 |

| Gurr and Acuqro [56] | 2018 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 3 P and 3 AP and 18 T and 48–60 Stu and 48–60 Par and 3 CC and 3 CSB and 3 SCM | 1 |

| Gurr, Drysdale, Longmuir, and McCrohan [57] | 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 3 P and 3 AP and 18 T and 48–60 Stu and 48–60 Par and 3 CC and 3 CSB and 3 SCM | 1 |

| Gurr et al. [58] | 2019 | 2 | N/A | N/A | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 3 P and 3 AP and 18 T and 48–60 Stu and 48–60 Par and 3 CC and 3 CSB and 3 SCM | N/A |

| Longmuir [59] | 2019 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and 1 AP and 6 T and 10–16 Stu. and 10–16 Par. and 1 CC and 1 CSB and 1 SCM | 1 and 3 |

| Gurr, Longmuir and Reed [60] | 2020 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Australia | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | 2 P and 2 AP and 12 T and 32–40 Stu and 32–40 Par and 2 CC and 2 CSB and 2 SCM | 1 and 3 |

| Pashiardis et al. [61] | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Cyprus | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 5 | 5 P and T and Par. and Stu | 4 and 6 |

| Pashiardis et al. [62] | 2012 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Cyprus | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | 2 P and T and Par. and Stu | 1 and 4 |

| Pashiardis and Savvides [63] | 2014 | 2 | N/A | N/A | Cyprus | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and T and Par. | 1 |

| Pashiardis et al. [64] | 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Cyprus | Qualitative study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | 2 P and 10 T and 6 Stu | 4 |

| Pashiardis et al. [65] | 2018 | 1 | 3 | 1 | Cyprus | Case study; Random sampling | 2 | 2 P and 10 T and 10 Stu | 4 |

| Yaakov and Tubin [66] | 2013 | 2 | N/A | N/A | Israel | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P | 1 |

| Tubin [67] | 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Israel | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 7 | P and AP and SLT and SCM and Sch Psy. And Sup. and External agents | 1, 3, 4, 6 and 7 |

| Notman [68] | 2009 | 1 | 3 | 1 | New Zealand | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and Stu. and Par. | 1 |

| Notman [69] | 2014 | 2 | N/A | N/A | New Zealand | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and senior T and T and Stu. and DP | 1 |

| Notman [70] | 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | New Zealand | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | 2 P and T and BT | 1 |

| Notman [71] | 2020 | 1 | 3 | 1 | New Zealand | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | 2 P and Senior leader and BT | 4 |

| Moller and Eggen [72] | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Norway | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 2 P and T and Stu. and Par. and LT and Emp. and UP and Ind. | 1 and 3 |

| Moller [73] | 2006 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Norway | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | T and Stu. and Par. and DO | 1 and 3 |

| Vedoy and Moller [74] | 2007 | 1 | N/A | N/A | Norway | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | 2 P and Stu | 1 and 3 |

| Moller, Vedoy, Prethus, and Skedsmo [75] | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Norway | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | T and 1 P | 1 and 2 |

| Moller, Vedoy, Prethus, and Skedsmo [76] | 2009 | 1 | N/A | 1 | Norway | N/A | 2 | T and 2 P | 1 |

| Moller and Vedoy [77] | 2014 | 2 | N/A | N/A | Norway | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and T | 1 |

| Ballangrud and Paulsen [78] | 2018 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Norway | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and Stu. and T and LT | 4 |

| Moller [79] | 2018 | 1 | N/A | 1 | Norway | Mix study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 8 T and 1 P and 8 Stu and 1 Sup. and 2 Deputy | 1 and 5 and 7 |

| Ballangrud and Aas [80] | 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Norway | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | 41 in total (2 P and T and Stu and Leaders) | 1 and 3 |

| Moral et al. [81] | 2017 | 1 | 1 | N/A | Spain | Qualitative study; Random sampling | 4 | 4 P and 14 T and 3/4 Par. and 4/5 Stu and Inspectors | 4 |

| González-Falcón, García-Rodríguez, Gómez-Hurtado, and Carrasco-Macías [82] | 2020 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Spain | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | P and T and Par. and Stu and 2 Outside agent | 1 |

| Santaella [83] | 2020 | 1 | 2 | N/A | Spain | Qualitative | 2 | 2 P | 3 and 4 and 1 |

| Höög, Johansson and Olofsson [84] | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Sweden | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | 1 CSB and 1 super and 12 Stu and 2 P and 6 T | 1 |

| Ärlestig [85] | 2007 | 1 | 3 | 1 | Sweden | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 6 T and 2 P | 1 and 5 and 6 |

| Johansson, Davis, and Geijer [86] | 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Sweden | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 2 P and 4 T and Stu | 1 and 2 and 3 and 6 |

| Ärlestig [87] | 2008 | 1 | 3 | 1 | Sweden | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 5 | 5 P and 25 T | 1 and 4 and 5 |

| Höög, Johansson, and Olofsson [88] | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Sweden | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | 2 P and T and Stu | 1 and 2 and 3 |

| Ärlestig and Törnsén [89] | 2014 | 2 | N/A | N/A | Sweden | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P | 1 |

| Day [90] | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | UK | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | P | 1 |

| Day [91] | 2014 | 1 | 2 | 1 | UK | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | P and Staff and Par. | 1 |

| Day, Gu, Sammons [92] | 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | UK | Mix study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | P and Staff and other colleagues | 1 and 2 |

| Day and Gu [93] | 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | UK | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 2 | P and Senior/Mid leaders and T | 4 |

| Gu, Sammons, and Chen [94] | 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | UK | Mix study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | P and Staff and stakeholders | 1 and 2 |

| Jacobson et al. [95] | 2004 | 1 | 2 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful and random sampling | 3 | P and T and Staff and Par. and Stu. (18 + 17 + 20 = 55 educators) | 4 and 6 and 7 |

| Giles, Johnson, Brooks, and Jacobson [96] | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful and random sampling | 1 | 1 P and 13 Faculty and 4 Staff and 18 Par. | 1 and 4 and 6 and 7 |

| Giles [97] | 2006 | 1 | 2 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful and random sampling | 3 | 3 P and 40 T and 15 Staff and 29 Par. | 4 and 6 and 7 |

| Jacobson et al. [15] | 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful and random sampling | 3 | P and T and Staff and Par. and Stu | 4 and 7 |

| Johnson [98] | 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | T and P and Par. | 1 and 7 |

| Giles [99] | 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | N/A | N/A |

| Ylimaki [100] | 2007 | 1 | 2 | 1 | US | Case study | 4 | P and T | 1 |

| Jacobson, Johnson, Ylimaki and Giles [101] | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and 1 AP and 1 CBT and 6 T and 6 Par. | 1 and 2 and 7 |

| Ramalho, Garza and Merchant [102] | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Case study;Purposeful sampling | 2 | 2 P and11 T and5 Adm. and12 Par. and11 Stu. | 1 and 4 and 5 and 7 |

| Garza, Murakami and Merchant [103] | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P | 1 |

| Jacobson, Johnson, and Ylimaki [104] | 2011 | 2 | N/A | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P and 1 AP and 1 CBT and 6 T and 6 Par. | 1 and 2 and 6 and 7 |

| Dugan, Ylimaki and Bennet [105] | 2012 | 1 | 3 | 1 | US | Case study | 1 | P and T and Par. | 1 |

| Murakami, Garza and Merchant [106] | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | P and T and Par. | 1 |

| Ylimaki et al. [107] | 2012 | 1 | 2 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful and random sampling | 4 | P and SCM and AP and CC and T and 6 Par. and 6 Stu. | 1 and 2 and 6 |

| Klar and Brewer [108] | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Mix study; Purposeful sampling | 3 | P and other stakeholders | 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and 6 |

| Klar et al. [109] | 2013 | 1 | N/A | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | P and Adm. and T and Staff and 6 Par. and 6 Stu. | 1 and 2 and 4 and 6 |

| Dugan and Bennet [110] | 2014 | 2 | N/A | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | P and T | 1 |

| Klar and Brewer [111] | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 2 P and 1 AP and 6 T and 1 Staff and 2 Par. | 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and 5 and 6 |

| Minor-Ragan and Jacobson [112] | 2014 | 2 | N/A | 1 | US | Case study; Purposeful sampling | 1 | 1 P | 1 |

| Findings | Microsystems | Meso- | Exo- | Macro | Chrono- | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stu Performance | SES | Culture | Stu Population | Location | Level | Parents, School Community | Sch Ranking | Policy | Political | Culture and Values | ||

| Success | Hi Lo | Hi Lo | Teacher leaving Behavioral issues | Diverse Homogeneous Needs | Urban Suburban Rural | Elem. Middle High | Supportive Negative | Reginal partnership | Pressure to increase scores, accountability | Ed. system Centralized Decentralized | By country | Over time |

| Qualities | Hi Lo | Hi Lo | Teacher leaving Behavioral issues | Diverse Homogeneous Needs | Urban Suburban Rural | Elem. Middle High | Supportive Negative | Reginal partnership | Pressure to increase scores, accountability | Ed. system Centralized Decentralized | By country | Over time |

| Practices | Hi Lo | Hi Lo | Teacher leaving Behavioral issues | Diverse Homogeneous Needs | Urban Suburban Rural | Elem. Middle High | Supportive Negative | Reginal partnership | Pressure to increase scores, accountability | Ed. system Centralized Decentralized | By country | Beginning, next, final stage |

| Success Indicators | Australia | Cyprus | Israel | New Zealand | Norway | Spain | Sweden | UK | US |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Student Outcomes | |||||||||

| Academic achievement, growth, % to college and up | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Student social and emotional development, empowered engagement, leadership, taking extracurricular courses | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Enrollment up/dropouts down | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 2. School Environment | |||||||||

| Supportive, positive, caring, learning environment, sense of community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Student bonds, good teacher–student relationships | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Disciplinary climate improved (e.g., attendance up, absence down, incidents down, student respect) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Inclusive for minority students, democratic, reduced racism, multicultural | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 3. Instructional Capacity | |||||||||

| High-level professional learning | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| High-quality teachers | ✓ | ||||||||

| Low staff turnover | ✓ | ||||||||

| High motivation, committed, trust | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Innovative curriculum/program | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Collegial, friendship, cordiality, collaboration | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 4. Community and Parent Support | |||||||||

| Parent involvement and support | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Partnering with community (e.g., local business, authority) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 5. Good Reputation/School Improvement | |||||||||

| School and principal awards, innovative | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Good Ofsted inspection report, school ranking, improvement and turnaround | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 6. School Physical Appearance and Resources | |||||||||

| Well tended, well resourced | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, J.; Day, C.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H.; Huang, T.; Lin, J. Successful School Principalship: A Meta-Synthesis of 20 Years of International Case Studies. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090929

Sun J, Day C, Zhang R, Zhang H, Huang T, Lin J. Successful School Principalship: A Meta-Synthesis of 20 Years of International Case Studies. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(9):929. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090929

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Jingping, Christopher Day, Rong Zhang, Huaiyue Zhang, Ting Huang, and Junqi Lin. 2024. "Successful School Principalship: A Meta-Synthesis of 20 Years of International Case Studies" Education Sciences 14, no. 9: 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090929

APA StyleSun, J., Day, C., Zhang, R., Zhang, H., Huang, T., & Lin, J. (2024). Successful School Principalship: A Meta-Synthesis of 20 Years of International Case Studies. Education Sciences, 14(9), 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090929