2. Background and Literature Review

Academic dishonesty is behavior that includes copying from colleagues during tests, copying homework, using unauthorized digital tools, and using plagiarism in academic assignments [

8]. Studying and identifying the causes of academic dishonesty is important in establishing preventive mechanisms and developing a system of means and tools that may be used in academic settings as well as in the education system as a whole [

11]. Researchers have examined the reasons behind academic dishonesty and whether there are factors that may influence people’s choice and desire to cheat. Thus, for example, according to Fishman [

12], morality plays a very important role in behaving with academic integrity. Fishman claims that academic integrity involves a personal obligation to the basic values of honesty, honor, fairness, trust, courage, and responsibility. A more recent study indicates that factors linked to a social-learning culture have a stronger presence in academia [

8]. Students rationalize their academic dishonesty by giving themselves various reasons and excuses for their behavior.

Studies have also indicated that students who engage in academic fraud are characterized by low self-efficacy, low class attendance, and an increased use of digital tools for learning and assessments [

13,

14]. Self-efficacy, defined as an individual’s belief in their ability to execute tasks successfully, plays a crucial role in academic behavior. Bandura emphasized that high self-efficacy may enhance motivation and academic performance, while low self-efficacy often correlates with more instances of academic dishonesty [

15]. Students with low self-efficacy may resort to cheating as a coping mechanism to deal with perceived academic challenges. The proliferation of digital tools and resources has made information more accessible, thereby increasing the opportunities for academic dishonesty. Websites offering pre-written academic papers and advanced AI tools like GPT software facilitate plagiarism and other forms of academic fraud [

16]. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated this issue by shifting many educational activities online, where monitoring and enforcing academic integrity has become more challenging [

17]. Class attendance is another critical factor influencing academic honesty. Studies show that regular class attendance is associated with higher levels of self-efficacy and fewer instances of academic dishonesty [

17,

18]. A physical presence in the academic environment fosters a sense of responsibility and commitment to academic integrity.

Ethics education is proposed as an effective measure to combat academic dishonesty. Emphasizing the importance of ethical behavior and the consequences of academic fraud may help inculcate a culture of integrity among students [

19]. Moreover, creating awareness about the long-term impact of academic dishonesty on the professional and personal life of students may deter them from engaging in fraudulent activities. Higher-education institutions play a pivotal role in preventing academic dishonesty. Strategies such as promoting academic integrity, providing training to the faculty on detecting and dealing with fraud, and using advanced plagiarism-detection software such as Turnitin are essential [

17,

19]. However, research indicates that these measures alone are insufficient and must be complemented by fostering a supportive academic environment that encourages honesty and integrity [

16].

There are several factors related to the higher-education system that contribute to academic fraud. (1) Universities do not promote the values of academic integrity very much. There is not enough emphasis in universities on following acceptable ethical codes [

19,

20]. (2) Professors do not receive sufficient incentives to fight academic fraud. The university budgets are largely dependent on the number of students and on research, and therefore, it is not worthwhile for professors to respond strictly to academic fraud. Professors do not view course examinations as an evaluation tool that is part and parcel of the course. Moreover, the exam questions are not always aligned with the course material and the syllabus, and professors do not always choose examination reference materials that will be allowed during the test [

21,

22]. (3) The teaching and evaluation methods used at universities are out of date and depend mainly on leaning by rote. There is a need to use more advanced methods that have been created following the development of AI. New methods of evaluation may be formed, with AI performing almost all the traditional evaluation tasks. It is necessary to consider the following questions: How may learning outcomes be evaluated when incorporating AI? How may AI be used as an evaluation aid? Is it at all possible or desirable to evaluate the process or the outcome? May a group assignment be evaluated as a learning outcome? Does the existence of generative AI (GenAI) provide new opportunities to reconsider why evaluation is needed [

23,

24]? (4) Students who act with academic integrity receive no incentive to report acts of fraud on the part of fellow students, because students who study together in academic groups develop strong feelings of belonging and solidarity toward each other [

25].

Studies show that academic fraud affects and predicts fraud and unproductive behavior at the future workplace [

26]. Moreover, academic dishonesty may be uncovered, unpredictably, many years later—for example, in 2012, the President of Hungary, Pál Schmitt, resigned due to allegations of plagiarism, and the Hungarian university revoked his 1992 PhD [

27]. Studies have been conducted for many years to understand the source and main reason for the phenomenon of academic dishonesty. Various studies worldwide and in Israel, such as a study that was conducted at Ariel University [

8], found numerous correlations between academic dishonesty and age, gender, demographic sector, religion, year of education, and more. Studies indicate a negative correlation between academic dishonesty and personal traits such as self-image, self-esteem, self-respect, optimism, self-confidence, skillfulness, and so on. It is suggested in the studies that a low level of these traits may be one of the reasons behind low academic achievements and a willingness to cheat. For example, a low emotional state affects the willingness to cheat [

28]. The most common reasons reported by students in various studies as driving their acts of academic fraud are internal reasons. For example, the study above-mentioned by Nitza Davidovitch and Liat Korn [

8] describes the characteristics of the “academic criminal” among students in Israel. Their results indicated a negative correlation between various self-perceptions and academic fraud. A dominant variable that was found to be related to academic integrity is self-efficacy.

An important factor that affects personal behavior is self-efficacy, that is, the individual’s belief in their ability to handle a task or situation. Self-efficacy gives the individual a sense of self-confidence that they are able to perform as expected of them [

29]. On the one hand, high self-efficacy leads to the exertion of greater efforts to reach goals. However, on the other hand, low self-efficacy leads to lower drive (lower motivation) and thoughts about failure. Positive beliefs form the basis for personal motivation and positive feelings in a given field when an individual interacts with their surroundings and significant others [

30]. A person’s self-efficacy is affected by the following factors to varying degrees: experience in performing tasks, watching the behavior of others, verbal convincing, and emotional arousal. Korn and Davidovitch [

8] also found that the frequency of cheating in tests was higher among students with a low grade point average (38.4%) compared to students with a higher grade point average (25.8%). The current study examined the relationship between the variables of self-efficacy and academic fraud, taking into consideration the effect of digital tools.

After more than 30 years, the Internet has increased the access to information and has enabled information to be spread to an unlimited number of learners who may edit and share the information via various tools. At the same time, the availability of online information has contributed to students copying from the Internet or sharing material with each other simply and easily to complete their academic studies successfully. In addition, various websites offer assistance in completing academic assignments, which encourages digital deception in an accessible and easy way and allows cheating to take place by purchasing ready-made academic papers online [

7,

31].

The coronavirus pandemic and its consequences have changed the educational scope as well as the students’ attitude toward the manner and essence of learning in an academic institution. From the point of view of the students, it was found that the attendance at classes and presence in the academic institution had significantly decreased in comparison to the pre-pandemic era [

32]. Students skip classes, do not take part in discussions, and sometimes do not even know their professor. Professor Yoram Shachar states, in his article “Mandatory Attendance” in Jokopost” [

33], that he struggles to bring his students to class and that, from a financial point of view, this struggle does not make much sense—he tries to provide them with as much benefit as possible from the product for which he gets paid (higher education), while they, the students, do their best to benefit as little as possible. Davidovitch and Dorot stated that the academic institution is responsible for creating a positive learning and social environment that will influence the students’ success and their motivation to learn [

34]. Classroom climate, in general, and student attendance on campus, in particular, may have a decisive impact on the students’ success in exams and assignments and may even lessen the phenomenon of academic fraud.

Academic fraud is conducted intentionally by students for the purpose of succeeding at their studies by using various dishonest methods [

35]. At colleges in the United States, plagiarism is widely used: more than 75% of students engaged in fraud during their studies, and 68% copied material from the Internet and used it in their academic work without properly referring to the source [

36]. To counter this, educational institutions must organize the learning process in a way that minimizes academic misconduct. It is challenging to research the topic of academic fraud because the main tool that is used is questionnaires in which participants are asked to report their own academic dishonesty. This method is paradoxical: it requires the survey participants to honestly report their dishonesty [

37].

After the development of software for identifying plagiarism such as Moss, PlagiServe, EduTie, and Turnitin, the job of uncovering plagiarism became easier; however, introducing this type of software into educational institutions did not have the desired effect. An example of this is shown in a study that was conducted in New Zealand on the prevention of plagiarism and included more than 500 participants. The study focused on the Turnitin software, which was used to identify plagiarism in academic exercises by locating excerpts from the exercises that could be found word-for-word on the Internet. Despite the fact that the teacher explicitly informed the students that the Turnitin software may be used on their work, almost a third of the students passed the first exercise by cheating. After receiving written notice from the teacher about having discovered plagiarism in their first exercise, only a third of the students who cheated refrained from cheating in the second exercise. Even when the Turnitin software was used, the number of students who engaged in plagiarism was high [

37]. The study shows that even the use of software to identify plagiarism does not prevent academic dishonesty.

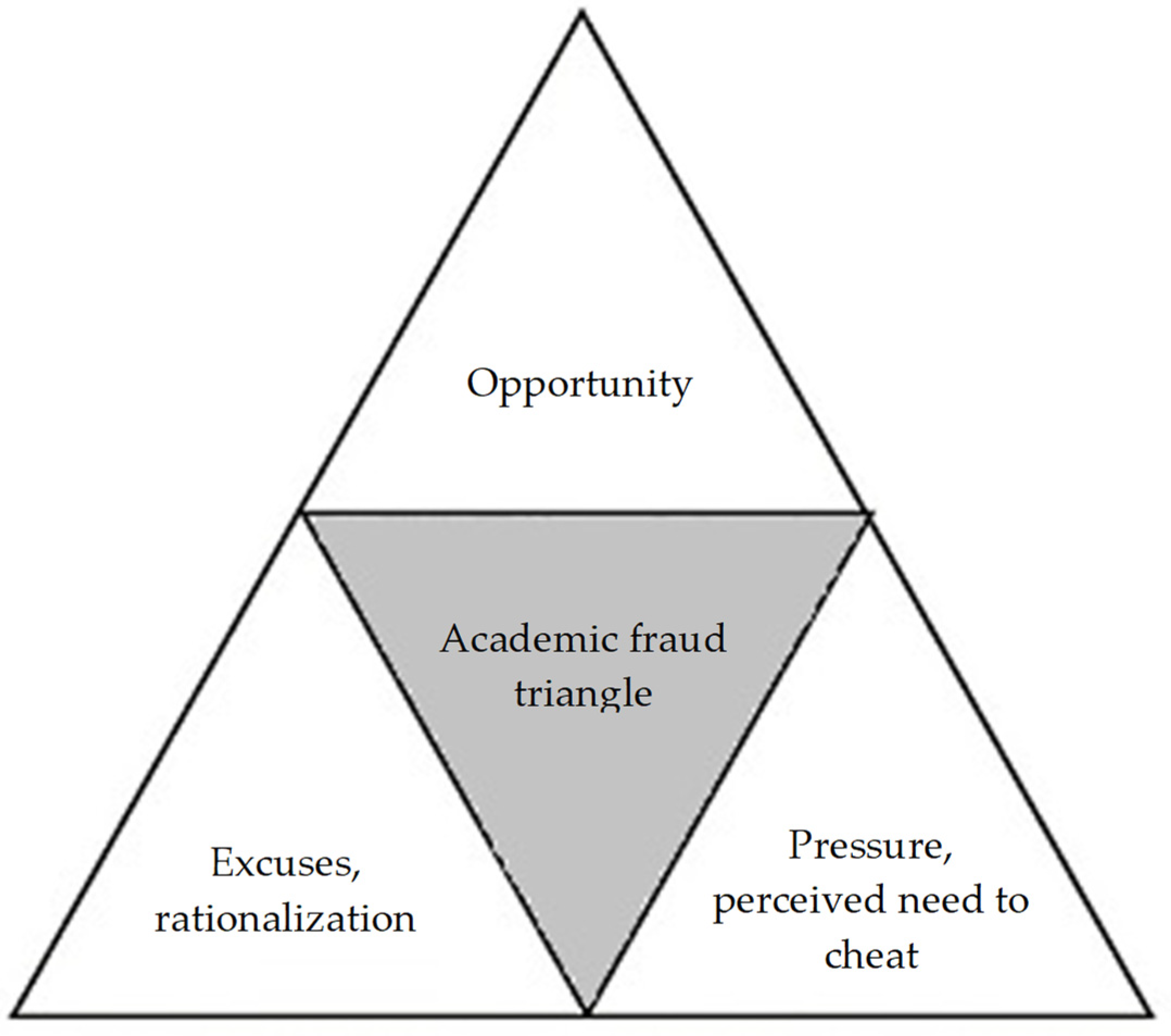

It is necessary to examine and identify the causes of academic fraud on both the theoretical and practical levels, since this will make it possible to create mechanisms and develop systems to prevent the fraud. One of these mechanisms is the “fraud triangle”. The fraud triangle model was presented in 1953 by the legal scientist Donald Ray Cressey, who claimed that every action committed by an individual (including fraud) must have a reason. This model divides the reasons into the following categories: pressures, opportunities, and rationalizations. The model was mentioned and renewed by American researchers J. Wentz, W. S. Albrecht, and T. Williams in the context of fraud in business. Their research hypothesis was that fraud occurred under three main conditions that together formed the so-called “fraud triangle”: (1) pressure from external circumstances (e.g., academic stress); (2) opportunity—the ability to perform acts of fraud that go unnoticed for a continued period of time (e.g., lack of supervision); and (3) rationalization—the fraudulent person’s ability to justify the fraud to themselves (e.g., justifying cheating by perceiving it as common practice). The researchers claimed that these three components exist in every case of fraud [

38,

39]. Addressing these factors through targeted interventions may help to reduce the number of instances of academic dishonesty.

Regarding higher education, the “fraud triangle” is used in scientific journalism in the United States in the context of academic fraud and is termed the “academic fraud triangle.” Marshall and Varnon explained the conditions for the students’ academic fraud through the example of student behavior during the exam period [

39]. They claim that students may be pressured (the first component of the fraud triangle) to achieve high grades on exams despite coming unprepared for the exams or having weak learning abilities. If, in addition, the opportunity presents itself (the second component of the fraud triangle) to access the answers to the exam, and the student knows that the academic institution does not actively fight against academic dishonesty, the student may justify the act of fraud through rationalizations and excuses (the third component of the fraud triangle): they may tell themselves that the teacher did not explain academic fraud, that the consequences for academic dishonesty at the academic institution are not severe, that everyone cheats, or that the exam on which they are cheating is only a practice exam and is not very important. They may go so far as to copy the answers during the exam [

40]. This model was examined at Semarang University in Indonesia and was found to be useful in explaining issues of academic fraud [

41].

The academic fraud triangle presents the principles of academic fraud: (1) each student has their own fraud triangle; (2) academic pressure and other external pressures may be present such as personal or financial difficulties, diseases, lack of time, learning problems, and so on; (3) indirect causes of pressure may exist such as a low self-image and a strong feeling of justice; (4) opportunities may present themselves at the academic institution such as weak supervision in in-class exams or no supervision in online exams or may stem from personal abilities of the student such as digital know-how, the ability to create cheat sheets, and access to previous exams; (5) rationalization—the student may come up with rationalizations to convince themselves to perform the fraudulent act. Rationalization is the main component of fraudulent behavior and is based on various personal opinions, stances, and views as well as the individual student’s personality and their belief that a lack of academic integrity is legitimate. The academic fraud triangle theory shows that it is possible to decrease the occurrence of academic fraud by diminishing one of the components of the fraud triangle. The shared task of both the university and the student is to diminish the components of the triangle and to take away from their value. For example, minimizing the opportunities for students to cheat and developing basic ethics among students may help overcome the recent outburst of academic fraud.

The literature highlights that academic dishonesty is a multifaceted issue influenced by individual traits such as self-efficacy, environmental factors such as class attendance, and the pervasive impact of digital tools. Preventive measures must be holistic, combining ethics education, institutional policies, and supportive academic environments to effectively combat academic fraud. Future research is needed to continue to explore innovative strategies and technologies for upholding academic integrity in the evolving educational landscape.

The purpose of the current study is to show that certain correlations exist between the variables of attendance at classes, self-efficacy, digital learning methods, and academic fraud as well as to examine the causes of academic dishonesty. The study emphasizes the importance of finding a solid solution to academic fraud and may contribute to the identification of the main problems related to academic dishonesty. The study may also significantly contribute to the improvement of the tools that are used to fight academic dishonesty and to the understanding of the phenomenon and its scope, especially during the current era in which digital tools are easily accessible and some of which aid in acts of academic dishonesty.

The research questions are:

Regarding the class attendance variable: Does class attendance affect self-efficacy among higher-education students and, if so, to what degree? Is there a relationship between class attendance and academic fraud in higher education and, if so, to what degree?

Regarding the self-efficacy variable: Does self-efficacy affect academic fraud among higher-education students and, if so, to what degree? Is there a relationship between self-efficacy and student achievements in digital learning and, if so, to what degree?

Regarding the digital learning methods variable: Does the use of digital learning methods affect student achievements and, if so, to what degree? Does the use of digital learning methods affect the frequency of academic fraud and, if so, to what degree?

Regarding the academic fraud variable: What are the factors that contribute to academic fraud among higher-education students?

The research hypotheses are:

The lower the self-efficacy, the greater the academic dishonesty.

The more digital learning methods are used, the greater the increase in academic dishonesty.

The higher the level of class attendance, the lower the self-efficacy.

The first two hypotheses were confirmed; however, the last hypothesis was not confirmed. The fraud triangle method was used here to show ways that may reduce academic fraud such as providing fewer opportunities to cheat and educating students on the natural consequences of their actions.

3. Materials and Methods

The current study is a mixed methods study that is based on quantitative comparative methods as well as the previous literature and personal observations. The study examined the case of students at a particular university. The data were collected via a three-part questionnaire (

Appendix A) that was adapted to the topic of the study. The data were collected between May and July 2023. The questionnaire was sent to 121 students including both men and women from Ariel University, Israel, through digital platforms as a WhatsApp QR code and a hyperlink to a Google form. The participants were randomly sampled from higher-education students between the ages of 19 and 50, with most of the participants aged 22. The sample is a convenience sample. Correlations between academic dishonesty, class attendance, self-efficacy, and digital learning methods were found.

The research instrument was a structured questionnaire that is often used to collect data in the social sciences and humanities. The questionnaire included items that, together, formed the research variables (class attendance, self-efficacy, digital learning methods, and academic dishonesty). Some of the items were taken from the existing questionnaires, while new items were added that were more specific to the topic of the current study. After filling out the demographic details, the participants rated the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always”. The data were processed using SPSS software, version 28, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA. The questionnaire was adapted from a questionnaire dealing with morality and tolerance toward deviance that was used in a study by Korn and Davidovitch [

8]. The questionnaire in that study was validated before use, and the calculated reliability stated there was α = 0.740. Therefore, we assumed that the questionnaire in the current study was valid and that the reliability remained the same. This level of reliability is considered to be adequate with regard to academic standards.

The research variables were class attendance, self-efficacy, digital learning methods, and academic dishonesty. To examine the class-attendance variable, the participants were asked to evaluate their level of attendance at classes on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). To determine the reliability of this variable, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient was calculated using SPSS. The internal level of reliability of this variable was found to be α = 0.848. To examine the self-efficacy variable, the participants were asked to rate the degree to which they believed that they were able to achieve their goals regardless of the external conditions and to overcome their daily life obstacles. The items were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). To determine the reliability of this variable, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient was calculated using SPSS. The internal level of reliability of this variable was found to be α = 0.859. To examine the digital learning methods variable, the participants were asked to rate their opinions of digital learning methods on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). To determine the reliability of this variable, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient was calculated using SPSS. The internal level of reliability of this variable was found to be α = 0.700. To examine the academic dishonesty variable, the participants were asked to rate their own behaviors on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). To determine the reliability of this variable, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient was calculated using SPSS software, version 28, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA. The internal level of reliability of this variable was found to be α = 0.943.

The data that were used for the regression analysis were collected from the participants with regard to the various research variables. First, data were collected from the responses of the 121 students to the research questionnaire concerning these variables. Next, Pearson correlations between various pairs of variables were calculated. Finally, linear regression analysis was performed to find the predictability of certain variables based on other variables.

The data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 28, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA. The correlations between academic fraud and self-efficacy and digital learning methods as well as between self-efficacy and class attendance, were calculated. The background variables are gender, religious sector, faculty, year of study, study track, level of religiosity, mother tongue, and year of birth. The independent variables are self-efficacy, digital learning methods, and level of class attendance. The dependent variables are academic dishonesty and self-efficacy. The researchers received approval from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences’ ethics committee to conduct the study, approval no. AU-SOC-ND-20231112.

4. Results

To find the correlations, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the variables was calculated. A significant (

p < 0.05) weak negative correlation (

r = −0.223) was found between self-efficacy and academic dishonesty. That is, the lower the level of self-efficacy, the higher the level of academic dishonesty. A significant (

p < 0.05) weak positive correlation (

r = 0.235) was found between digital learning methods and academic dishonesty. That is, the greater the use of the Zoom digital platform for lectures and exams, the greater the increase in academic dishonesty behaviors. In addition, the correlation between class attendance and self-efficacy was examined. A significant (

p < 0.05) positive and almost strong correlation (

r = 0.446) was found between these two variables. That is, the higher the level of class attendance, the higher the level of student self-efficacy (

Table 1). Moreover, a significant positive correlation was found between the year of study and academic dishonesty (

Table 2). This correlation indicates that the more advanced the year of study, the greater the increase in academic dishonesty.

Regression Analysis

Significant correlations were found between self-efficacy and academic dishonesty and between digital learning methods and academic dishonesty as well as between self-efficacy and class attendance. These correlations allowed us to predict the level of the variables based on the other variables, as detailed below:

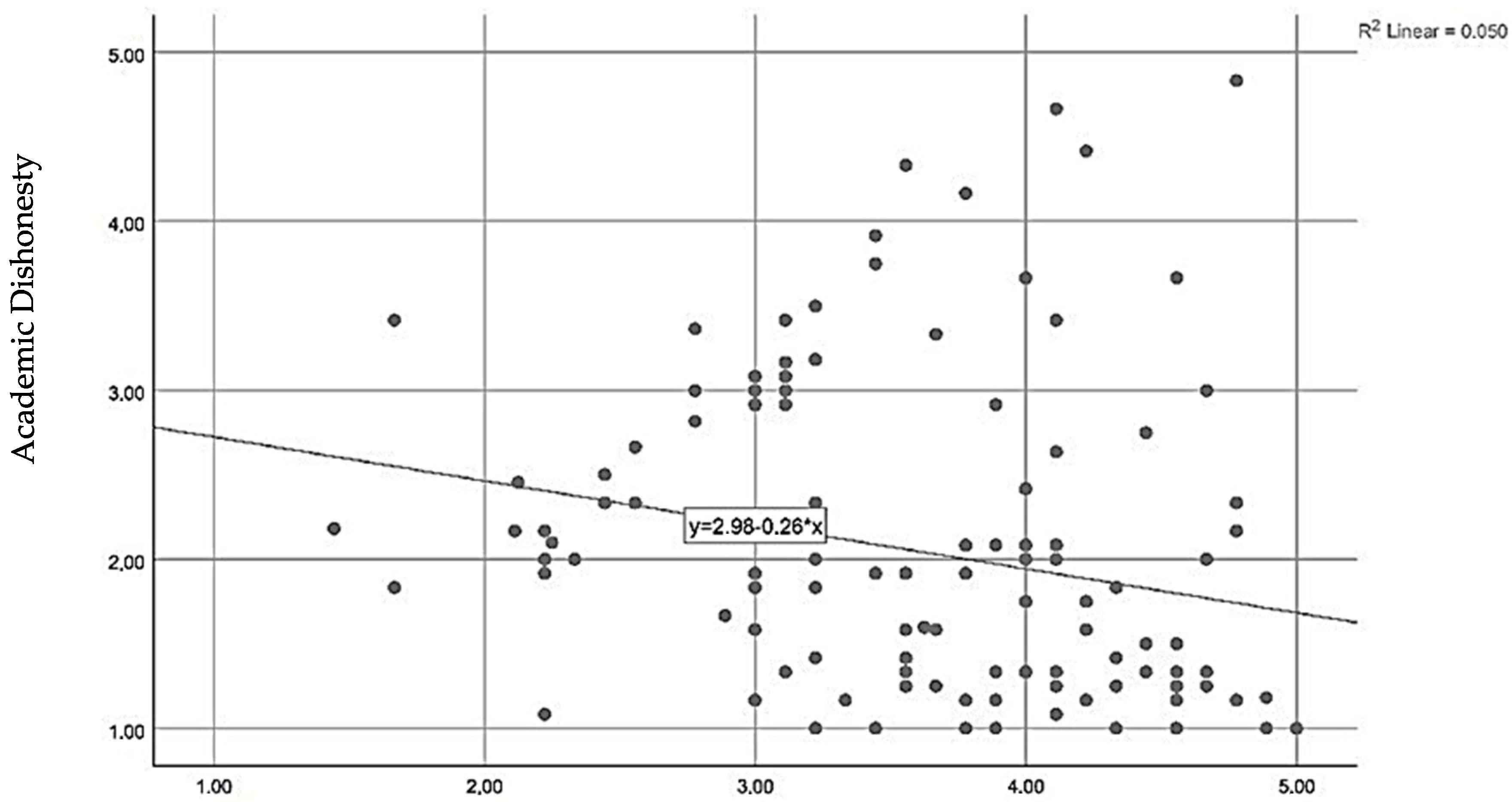

There was a systematic linear variation in variable Ŷ (academic dishonesty) as a function of variable X (self-efficacy). The regression data are shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 3.

After performing the linear regression analysis, the equation for predicting academic dishonesty based on self-efficacy was found to be Ŷ = − 0.26x + 2.98. The R value was found to be −0.223, R squared was found to be 0.050, the adjusted R squared value was found to be 0.041, and the SE of the estimate was found to be ~0.914. The coefficients that were calculated for the function constant (2.98) were: b = 2.984 and SE = 0.395 (unstandardized coefficients); t = 7.549; and p = 0.000. The coefficients that were calculated for the independent variable of self-efficacy were: b = −0.260 and SE = 0.106 (unstandardized coefficients); β = −0.223 (standardized coefficient); t = −2.460; and p = 0.015. The hypothesis was confirmed: the lower the value of the self-efficacy variable, the higher the increase in academic dishonesty [R = −0.223, p < 0.05, F (1, 116) = 6.050]. The self-efficacy variable explained 5% of the variance in the academic dishonesty variable.

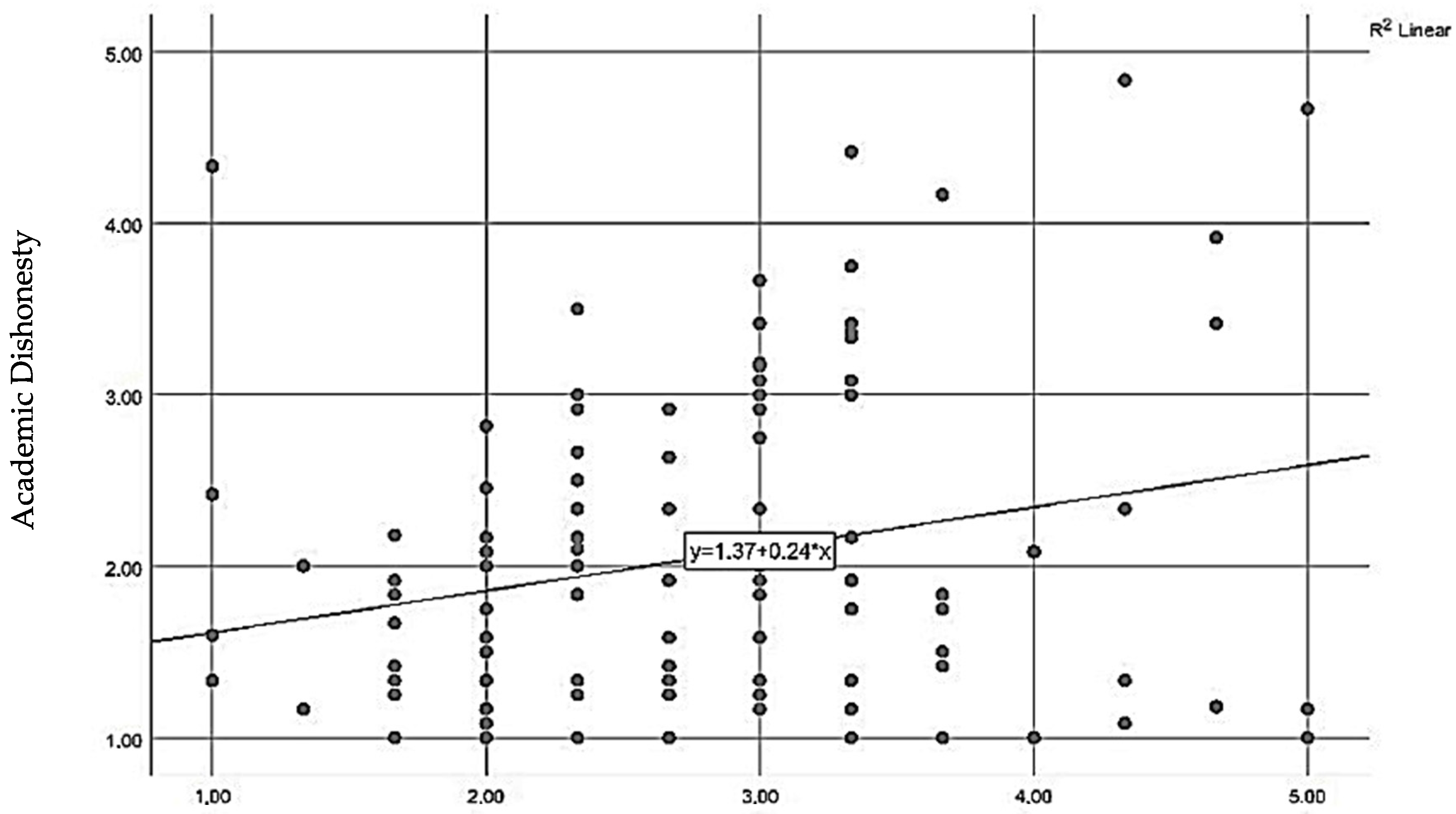

There was a systematic linear variation in variable Ŷ (academic dishonesty) as a function of variable X (digital learning methods). The regression data are shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 4.

After performing the linear regression analysis, the equation for predicting academic dishonesty based on digital learning methods was found to be Ŷ = 0.24x + 1.37. The R value was found to be 0.235, R squared was found to be 0.055, the adjusted R squared value was found to be 0.047, and the SE of the estimate was found to be ~0.912. The coefficients that were calculated for the function constant (1.37) were: b = 1.369 and SE = 0.269 (unstandardized coefficients); t = 5.093; and p = 0.000. The coefficients that were calculated for the independent variable of digital learning methods were: b = 0.244 and SE = 0.094 (unstandardized coefficients); β = 0.235 (standardized coefficient); t = 2.606; and p = 0.010. The hypothesis was confirmed: the higher the value of the digital learning methods variable, the higher is the increase in academic dishonesty [R = 0.235; p < 0.05; F(1, 116) = 6.792]. The digital learning methods variable explains 5.5% of the variance in the academic dishonesty variable.

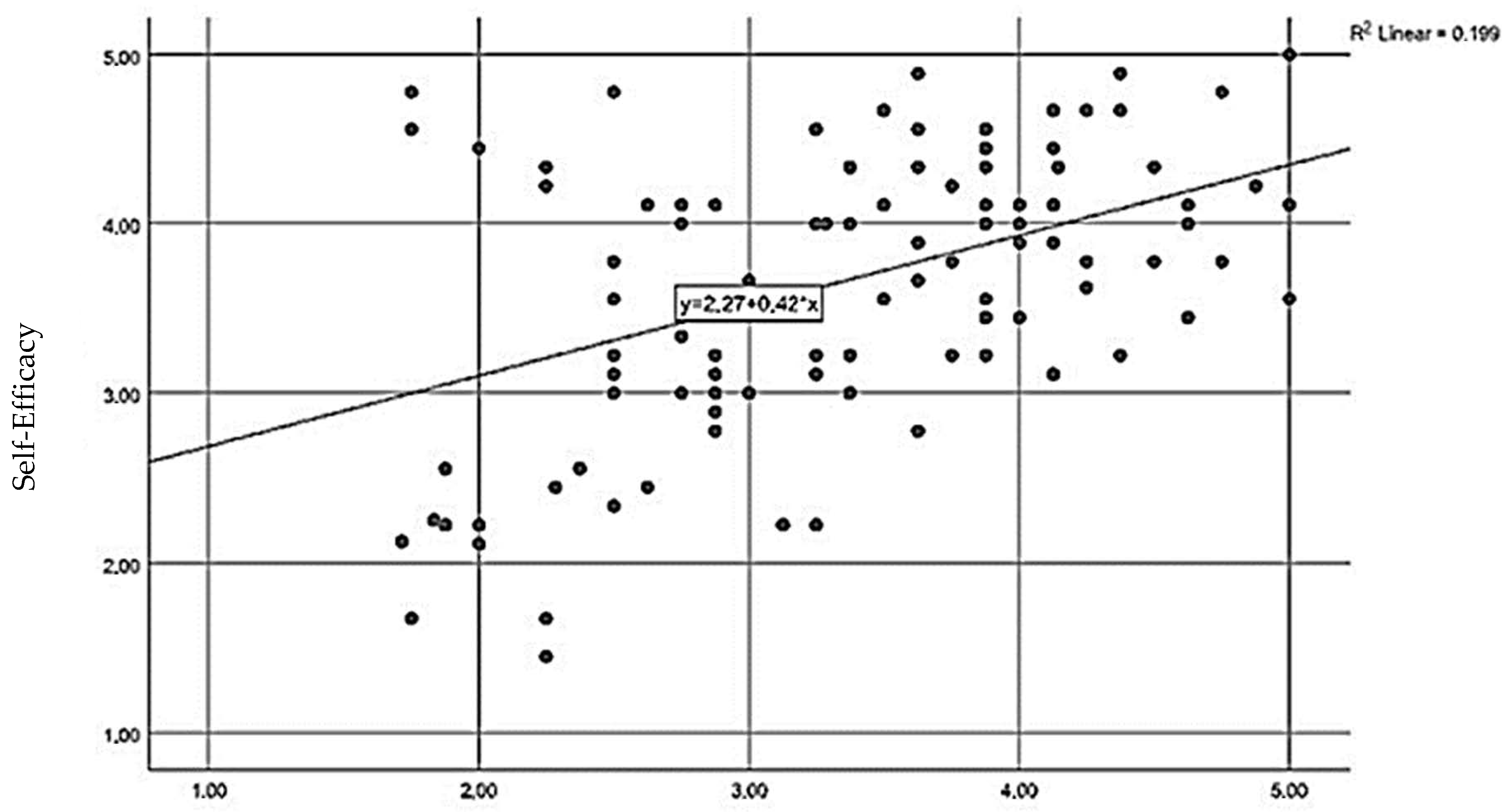

There is a systematic linear variation in variable Ŷ (self-efficacy) as a function of variable X (class attendance). The regression data are shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 5.

After the performing linear regression analysis, the equation for predicting self-efficacy based on class attendance was found to be Ŷ = 0.42x + 2.27. The R value was found to be 0.446, R squared was found to be 0.199, the adjusted R squared value was found to be 0.192, and the SE of the estimate was found to be ~0.718. The coefficients that were calculated for the function constant (2.27) were: b = 2.271 and SE = 0.266 (unstandardized coefficients); t = 8.540; and p = 0.000. The coefficients that were calculated for the independent variable of class attendance were: b = 0.415 and SE = 0.077 (unstandardized coefficients); β = 0.446 (standardized coefficient); t = 5.68; and p = 0.000. The hypothesis was not confirmed: the higher the value of the class attendance variable, the higher the self-efficacy [R = 0.446; p < 0.05; F(1, 116) = 28.820]. The class attendance variable explained 19.9% of the variance in the self-efficacy variable.

5. Discussion

HEIs have great influence on the future of students including their career choice, their progress in life, their income level, and various social aspects of their lives. Therefore, the main goal of education, in general, and of higher education, in particular, is to create human capital that will later influence the quality of education and the social-economic systems [

42]. However, this goal may not be reached if there exists an ethical educational problem such as academic dishonesty. Academic dishonesty also causes graduates to enter their jobs with a low level of education, unprepared, which is especially problematic in fields that involve public safety [

10].

The current study explored several important issues regarding the frequency, type, and scope of the phenomenon of academic dishonesty among students in a case study of a sample of students from Ariel University, Israel. The relationship between class attendance and academic dishonesty, between self-efficacy and academic dishonesty, and between digital learning methods (online learning) and academic integrity were examined. The uniqueness of the study lies in its examination of the relative influence of class attendance, self-efficacy, and digital learning on academic fraud based on the “fraud triangle model”.

The research correlations were determined by analyzing data that were collected from 121 students. Most of the participants reported having engaged in academic fraud. In the academic dishonesty questionnaire, 5.4% stated that they always cheated, and only 50.2% stated that they never cheated. That is, approximately half of the participants who answered the questionnaire did not oppose academic fraud and actually engaged in academically fraudulent behavior. However, since the results were obtained based on self-reporting, it can be assumed that the real number of fraudulent students is even greater than the reported number, and that the self-reporting method may be the reason that not all the research hypotheses were confirmed. It may be concluded from the research that in a class of 20 students, at least one student always cheats; moreover, half of the students do not hesitate to cheat when the opportunity arises.

The findings show that a significant negative correlation exists between self-efficacy and academic dishonesty. This correlation is supported by many other studies such as the study by Simon Moss et al. [

43], in which the authors showed, based on the existing literature, that a specific combination of circumstances and psychological attributes, of which self-efficacy plays an important role, cultivates academic fraud. In the current study, the findings showed that a significant positive correlation exists between digital learning methods and academic dishonesty. This correlation is supported by American researchers who claim that, following the introduction of digital learning technologies into HEIs, and, due to the popularity of these technologies, students now have a new opportunity of “electronic cheating”, which leads to a higher rate of academic fraud than exists in courses that do not use technological methods [

44]. However, no previous studies have examined the correlation between class attendance and academic dishonesty. Therefore, the current study, which relied on the previous literature, did not examine this correlation.

A model that may be useful in examining the causes of academic fraud is the “fraud triangle model”, which presents the possible reasons for committing fraud. This model was created more than 50 years ago. Many studies were conducted in an attempt to improve and renew the model, and thus the “fraud diamond model” and the “fraud pentagon model” were created, with partial success [

7]. To adapt the “fraud triangle model” to higher education, researchers created the “academic fraud triangle model” [

39]. The components of this triangle, as shown in

Figure 4, which relate to the environmental and personality characteristics of the fraudulent student, are: (1) the perceived need to cheat due to reasons such as illness, jealousy, lack of money, exam pressure, pressure from parents, greediness, low self-esteem, and low self-efficacy; (2) the opportunity to cheat such as tests and exercises that are not under the teacher’s scrutiny, knowledge regarding ways to cheat, free or paid cheating services, courses in which attendance is voluntary, tests during which students are allowed to leave the room to use the bathroom, lenient punishment for cheating, procedures that enable cheating (use of technological methods, the option to use the bathroom during exams, online exams); and (3) rationalizations for cheating such as convincing oneself of the legitimacy of cheating (“it won’t hurt anyone”, “everyone cheats”, “the teacher is unfair”), cheating to save time, laziness, lack of interest in the topic of the course, and believing that it is okay to cheat (cheating culture).

This model includes all the research variables as possible causes of academic fraud. According to the model, minimizing the causes of academic fraud, which are the components of the triangle, will minimize the cases of academic dishonesty. This theory is supported by the results of the current study, which show that the higher the level of self-efficacy and the less use there is of digital learning methods, there will be less academically fraudulent behaviors. The academic triangle fraud model may serve as a tool for understanding the varying complex types of academic dishonesty and their causes, and this, in turn, may provide information regarding the totality of methods that may be used to promote academic integrity in the most efficient manner.

The research questionnaire included additional background variables that were not examined in the analysis: gender, religious sector, faculty, year of study, study track, level of religiosity, mother tongue, and year of birth. The potential effects of these variables on the research results, based on the previous literature, are explained below:

Gender: The perceptions and behaviors of men and women may differ from each other with regard to academic integrity, class attendance, and the use of digital learning methods. Previous studies have shown that women often tend to behave more ethically than men, which may lead to lower levels of academic dishonesty among women [

45,

46,

47,

48].

Religious sector: The effect of the religious sector to which the participant belongs may be significant, since religious values may affect the student’s perception of academic integrity and responsibility. Religious students may show higher levels of class attendance and lower levels of academic dishonesty compared to non-religious students [

47,

49].

Faculty: The effect of the faculty to which the student belongs on the study results may be due to the culture and values that are acceptable in the particular faculty. For example, exact sciences are high-risk fields and therefore students majoring in these disciplines may be more tempted to cheat [

50].

Year of study: The effect of the year of study may be significant, since students in advanced years may be more aware of the importance of academic integrity and the risks of dishonesty. However, students in their first years may be less experienced and aware, and therefore may display higher levels of academic dishonesty than senior students [

48].

Study track: The effect of the study track may be evident in the differences between practical and theoretical study tracks, where theoretical tracks more greatly emphasize the importance of academic integrity. Different tracks may also use digital learning methods to various degrees, and this may have affected the results of the current study [

48].

Level of religiosity: Similarly to the religious sector, the personal level of religiosity may affect the perceptions and behaviors of students regarding academic integrity. Very religious students may display lower levels of academic dishonesty and make less use of digital tools for fraudulent purposes [

47,

49].

Mother tongue: A student’s mother tongue may affect their level of comfort in participating in the classroom and in completing study exercises. Students whose mother tongue differs from the language in which their academic course is being taught may have additional difficulties, which may lead to higher levels of academic dishonesty [

51].

Year of birth: The effect of the year of birth on the results of the current study may be expressed as via the differences between students of various generations, where students who are more senior may display greater responsibility and behave more ethically concerning their studies. In contrast, younger students may be more exposed to technology and more often use digital tools to cheat than older students [

52].

In summary, the effect of the variables that were examined in the questionnaire is somewhat complex regarding the behavior and perception patterns among higher-education students. It is important to understand the effect of each variable when formulating recommendations and interventions for the prevention of academic dishonesty and in striving to increase awareness toward integrity and ethical behavior in HEIs.