1. Introduction

Vocabulary, as one of the crucial components of language, significantly impacts learners’ ability to acquire a foreign language [

1]. A restricted vocabulary can hinder the ability to use suitable words, structures, and functions for effective communication. Highlighting the critical role of vocabulary acquisition, Schmitt [

1] asserts that “lexical knowledge is central to communicative competence and to the acquisition of a second language”. To improve vocabulary teaching, a variety of emerging technologies and multimodal instructional tools have been used. Among other advanced technologies, immersive technologies like virtual background (VB, also referred to as “green screen technology”), virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR) provide learners with an experiential process of language learning in a simulated environment [

2,

3,

4].

For LOTE (languages other than English) learners, in addition to the vocabulary challenges in foreign language learning, concerns have been expressed about their uncertainty about the importance of mastering a LOTE and their decreased motivation for such learning [

5,

6]. More specifically, individuals’ desire to expand their multilingual repertoire, which has been identified as a crucial element of their motivation for language learning, was not widely considered by LOTE learners [

7]. A significant obstacle to fostering motivation among LOTE students is their restricted exposure to the LOTE within their immediate environments [

8]. Insufficient experience with the target language during the learning process can lead students to underestimate the value of that language in their specific context and gradually lose interest in learning it. Therefore, the key to boosting learning motivation is to enrich their imaginative experiences with context-specific scenarios. In light of these considerations, green screen technology emerges as a promising solution to these challenges by providing a more dynamic and interactive learning environment, thereby significantly enhancing learning effectiveness and the overall educational experience.

VB is a technique in which the original background of a scene is replaced by a selected image. According to Oppenheimer et al. [

9], using VB in presentations can make them more interesting and educational, effectively engaging elementary school students in exploring language science concepts. In a study carried out by Hamzah and Abdullah [

10], it was found that the use of green screen technology creates a favorable environment to improve students’ verbal engagement during English lessons. Valle and McConkey [

11] described how students can take personalized video trips around the world and tell their stories in the target language (i.e., Spanish) based on their own proficiency level. They also reported various benefits of green screen technology in language learning, including increased motivation, improved cooperation, effective language acquisition, and a deeper appreciation of different cultures.

However, compared to its counterparts in technology-based education (i.e., VR and AR, see below), VB has received less research attention. To address the identified gaps in empirical research, this study aims to explore the effectiveness of using green screen technology for vocabulary learning, especially for location and clothing vocabulary. The following research questions have been formulated throughout this research, which appears to be the first attempt to apply green screen technology to vocabulary learning:

To what extent, if any, does the use of VB help students improve their French vocabulary learning?

Is VB more effective for enhancing students’ learning of location vocabulary or clothing vocabulary?

What are the students’ perceptions of this new technology?

2. Literature Review

The integration of emerging technologies such as VR and AR into instructional activities has been a subject of increasing research in recent years. These technologies have been shown to provide immersive, interactive, and exciting learning experiences [

12] that can significantly enhance students’ motivation and learning outcomes. The immersion offered by VR creates simulated environments in which learners can explore and interact. Tai et al. [

13] examined the use of VR in vocabulary learning and found that compared with traditional vocabulary learning methods, VR improves students’ vocabulary learning and retention because it provides an authentic, learner-centered, and immersive language learning platform.

In addition to authentic and immersive learning experiences, contribution to cognitive development is another key component that supports learning in virtual contexts. Lan et al. [

14] studied the effects of several learning methods on learning Mandarin Chinese as a second language. They compared traditional learning methods to virtual technologies from cognitive and linguistic perspectives. The findings indicated that the learning trajectory of the participants in the virtual environment progressed faster than that of those in the traditional context. In the virtual environment, the simulated experience may have aided learners in understanding and constructing their own conceptual representations of words.

Some VR/AR research has also illustrated the manifestation of positive emotions [

15] and the enhancement of learning motivations. Chiang et al. [

16] found that the use of an AR-based mobile learning approach enabled students to have significantly higher motivations in attention, confidence, and relevance dimensions than those who learned with a conventional approach.

Interactivity has also an important impact on the learning experience of VR/AR-based learning. Dunleavy and Dede [

3] argued that AR technology allows participants to interact with digital content that is integrated into the real-world environment, and to construct their own interpretations of reality from this physical interaction and the social interactions with others.

As an immersive technology akin to VR and AR, VB may also enhance the learning experience by narrowing the gap between the virtual and the real world. While VR and AR have been studied in educational contexts, the literature on the application of green screen technology is less prevalent, especially for its application in vocabulary learning. Despite the rapid development of technology, it cannot be denied that the application of VR in education still faces many challenges. For VR-based language learning, the majority of studies focused on using non-fully immersive VR systems via computers, where users navigate virtual environments through a mouse and a keyboard [

17]. Furthermore, it is particularly difficult for language teachers to implement VR-based language learning studies, due to the high cost of VR devices [

18].

Despite the growing body of theoretical and empirical research supporting the educational benefits of VR and AR, the literature on VB is comparatively sparse. However, the potential of VB to enrich educational experiences should not be overlooked, as the underlying principles of interaction, immersion, and engagement that characterize VR and AR technologies are also applicable to VB. Examining case studies of VR and AR in educational contexts provides valuable insights into how green screen technology can similarly enhance learning efficiency. Due to the pandemic outbreak in 2020, the use of virtual classrooms and VB technologies has seen wider application, and the necessity for green screen studios (or even green backgrounds) has been avoided. Online meeting software like Zoom (5.2.0 or higher) and Tencent Meeting (1.3.0 or higher), along with other green screen applications, can now achieve real-time background transformations, substituting videos and live-shot backgrounds with any image desired. Consequently, with the use of more convenient, affordable, and readily available equipment, green screen technology, which allows for the manipulation of backgrounds to create various scenarios or contexts, shares VR and AR’s potential to transform the learning environment into a dynamic and interactive space. These features are particularly relevant to vocabulary learning, where context and visual cues play critical roles in comprehension and memorization [

19].

According to dual coding theory [

20], the general cognition process involves the simultaneous activities of both verbal and non-verbal systems to facilitate understanding and memory retention. While the verbal system is specialized in dealing with linguistic information, the non-verbal system is specialized in processing sensory and imagery information. Verbal and non-verbal systems can both be used to represent [

20] or retrieve [

21] information. Therefore, dual coding theory and related research can contribute to the field of vocabulary acquisition in foreign language learning. Essentially, vocabulary retrieval involves two distinct memory codes: imagery codes, which include mental imagery or visual representations of the information, and verbal codes, which involve a verbal statement or a word’s definition. The dual encoding of new vocabulary through both imagery and verbal codes can be more productive than the effectiveness of solely verbal encoding [

22]. Therefore, green screen technology, by facilitating the creation of vivid, contextual visual backgrounds, should enhance the imagery encoding process. By integrating green screen backgrounds with the teacher’s live explanations, this technology allows for the integration of both verbal and imagery information, potentially leading to improved vocabulary learning outcomes in foreign language education.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context and Participants

Conducted at a prestigious university in China, a total of 58 students participated in the study. The study involved two separate groups: a control group of 25 participants and an experimental group of 33 students. The two groups took the same French course but were in different classes taught by the same teacher, which can ensure uniformity in teaching methodology and course content across both groups. The participants, consisting of students from all academic departments across the university, were native Chinese speakers with English as their first foreign language and French as their second.

Table 1 below summarizes the demographic information of the participants. At the beginning of the study, the students had approximately two months of French language instruction, starting from a baseline of zero knowledge before taking the French course. Moreover, students and teacher participants had no prior experience of using green screen technology for language learning/teaching, which ensured that any observed differences in vocabulary acquisition could be attributed to the use of green screen technology rather than pre-existing knowledge or familiarity with the learning tool.

3.2. Pedagogical Design and Materials

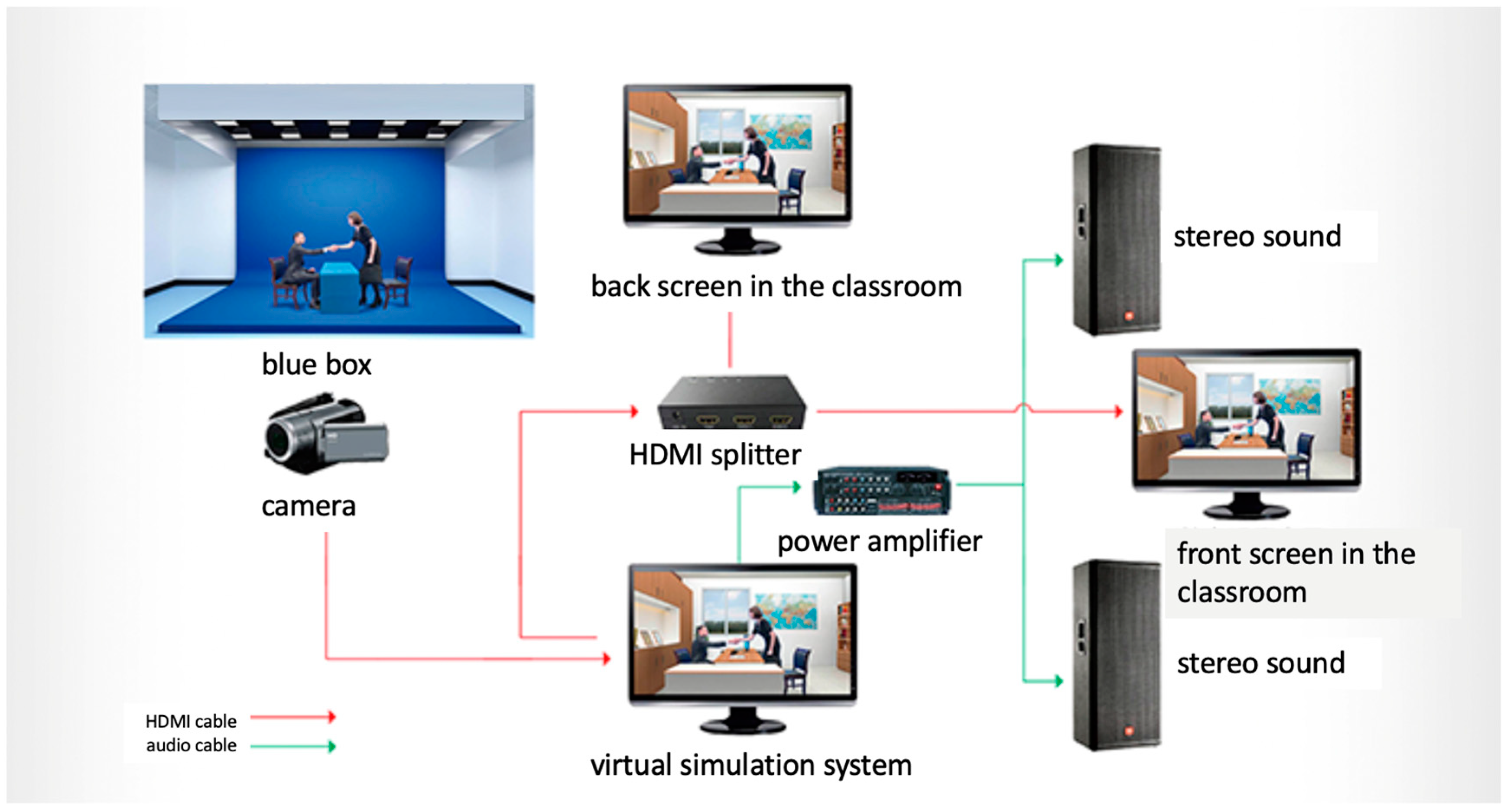

The study was conducted in the 2022–2023 Spring Semester and the 2023–2024 Autumn Semester. The green screen-based activities were carried out in a green screen classroom, which utilizes virtual simulation technology to achieve real-time switching between different teaching scenarios (as shown in

Figure 1, where the blue box in the picture represents the green screen background in the classroom). (Although the study was conducted in a green screen classroom, some online meeting software like Zoom and Tencent Meeting are found to be able to achieve the same effects after several trials.) During the teaching session, the teacher stood in front of the green screen, and the background system performed real-time keying of the teacher, overlaying the processed video with the virtual environment and transmitting it in real-time to the front and back screens of the classroom. Students in the classroom could thus receive an immersive experience by watching the overlay video.

The test and the pedagogical procedure were set by referring to students’ routine learning performances. Both the control group and the experimental group learned the same lessons before the mid-term exam, which took place before the intervention of green screen-based learning. After the mid-term exam, students learned the 26 selected words of two different types of vocabulary, specifically location and clothing-related words (see

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively), in two different lessons. In the control group, students first followed a lectured-based procedure of French vocabulary teaching and learning in university: in the 30 min vocabulary learning session of each lesson, the words were introduced and explained one by one by providing meanings, examples, and sometimes cultural or contextual notes relevant to each word. After the introduction and the explanation, students were required to do traditional vocabulary exercises which included repetition, matching exercises (linking French words with their Chinese translations), and fill-in-the-blanks exercises in class.

In the experimental group, students were required to learn the same 26 selected words in two vocabulary learning sessions of 30 min each. In the beginning, the words were introduced and taught the same way as in the control group. Then, the traditional word memory exercises were replaced by activities that incorporated green screen technology. These activities were designed to simulate real-life scenarios and contexts in which the target vocabulary could be used. Each of our green screen-based activities went through a piloting and editing process through which the teacher could receive feedback from several other students before the experimental process. In the location words’ learning session (see

Figure 2 for a screenshot of the virtual environment of the location words’ learning), the teacher stood and moved in front of the green screen, changing her position relative to the reference objects or people in the virtual environment. Participants could observe the teacher’s real-time location in virtual environments through the screens and hear sentences containing the corresponding vocabulary. They were also invited to interact with the teacher by answering questions, describing scenarios, and requesting the teacher (or other students in the class) to move to specific positions. In the clothes vocabulary learning session, participants could see the teacher presenting the target vocabulary in real-life contexts in which the word could be used (e.g., clothing store, designer studio, etc.). In the meantime, they were asked to interact with the teacher by answering questions, describing scenarios, and requesting the teacher (or other students in the class) to indicate different clothes.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3.1. Vocabulary Tests

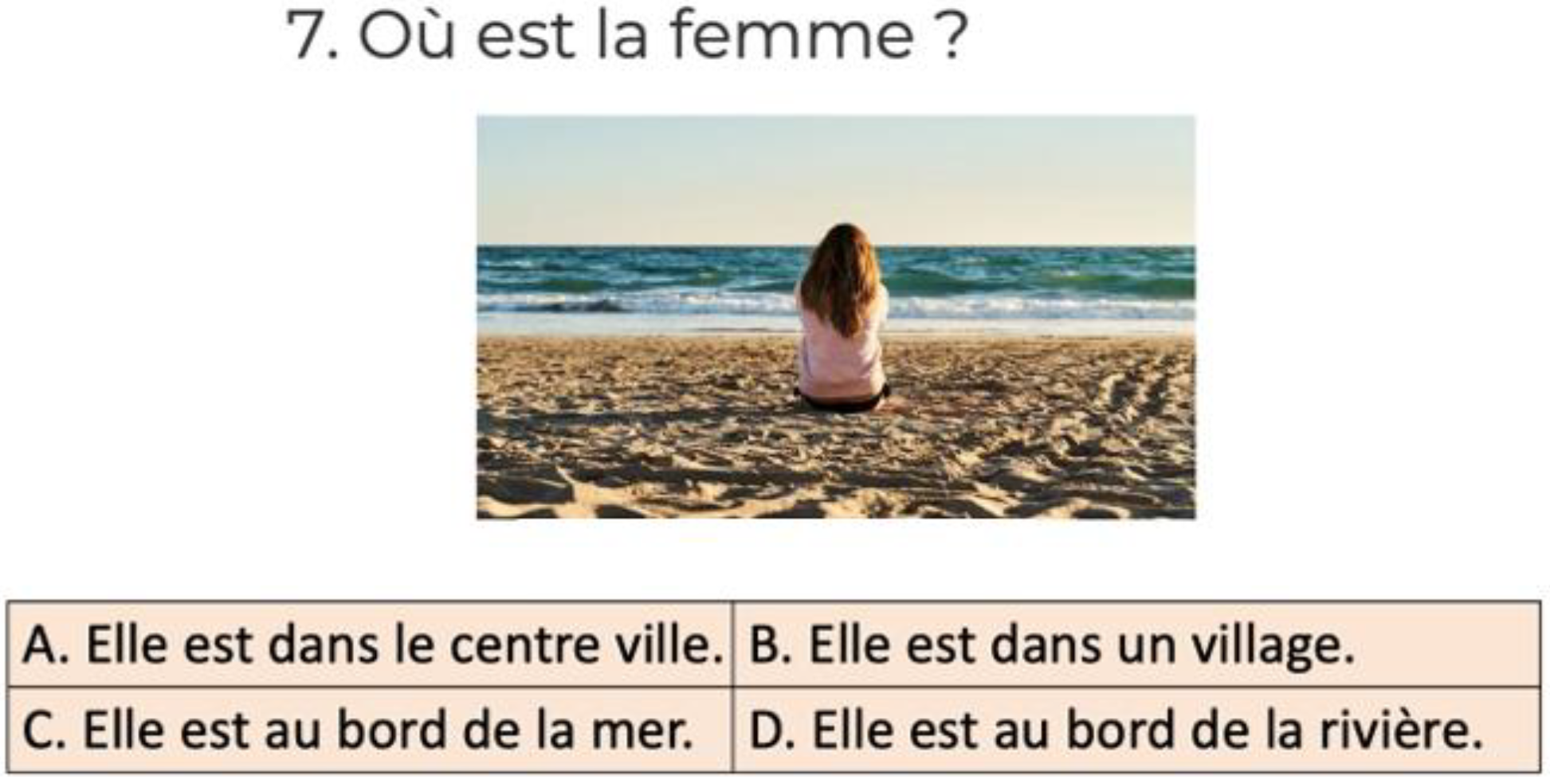

At the end of each vocabulary learning session, students in both groups were required to complete a vocabulary test to measure the learning results. Each vocabulary test consisted of eight items, and for each item, students were asked to choose the correct answer from four options of the same type based on the provided image (see

Figure 3 for an illustrative example). Similar delayed vocabulary tests for the two types of vocabulary were carried out 14 days after the vocabulary learning sessions of each group.

3.3.2. The Green Screen-Based Learning Questionnaire

At the end of the semester, students in the experimental group completed a five-point Likert-scale questionnaire (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), which was intended to understand the participants’ perceptions regarding their experience of using green screen technology for language learning. The items of the questionnaire were adapted with reference to several studies on computer-assisted language learning and modified to align with the theoretical framework of the present study. Four dimensions, including (1) authenticity and immersion, (2) cognitive and understanding, (3) motivation and emotion, and (4) interaction and exploration, were investigated. The adapted questionnaire was discussed with a senior researcher in the field of language learning and slightly modified in light of her feedback. A descriptive analysis of the questionnaire was carried out to provide an overview of the students’ participatory experiences.

3.3.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

Along with the learning questionnaire, semi-structured interviews with five participants of different levels (according to their mid-term exam scores) were organized to further understand students’ learning experiences. Each interviewee was requested to describe their learning experience, including challenges encountered in green screen-based learning, attitudes towards the new teaching method, and the advantages of learning with green screen technology. All interviews were transcribed and later confirmed by the interviewees for accuracy. A thematic approach was applied to the qualitative analysis of the transcription. The interviews (as well as the above-mentioned questionnaire) were conducted in Chinese to ensure better understanding and provoke deeper reflection from the interviewees.

4. Results

Drawing on the research questions outlined in the Introduction, this section provides a detailed presentation of the major findings derived from our collected data. In the current study, the results from both the quantitative and the qualitative data are presented, offering evidence for the contribution of the green screen-based application in vocabulary learning.

4.1. Difference Analysis of Language Learning Abilities

Before testing students’ vocabulary learning performance, their language learning abilities were assessed to determine if there were any differences between the control group and the experimental group. For all the participants, their language learning abilities were evaluated by their mid-term exam scores. The exam, consisting of questions on vocabulary, grammar, and comprehensive language use, lasted for one hour and had a total score of 15 points. An independent sample

t-test was used to determine the differences in French language learning abilities between the two groups before the experiment. The results (see

Table 4) indicated that there was no significant difference in the language learning abilities of the two groups.

4.2. French Vocabulary Learning Performance

Descriptive statistics and independent sample t-tests were conducted to analyze the results of the vocabulary tests and determine if there was a difference in the students’ vocabulary acquisition. As

Table 5 and

Table 6 show, the mean scores for the vocabulary tests were 5.080 for the control group 6.515 for the experimental group immediately after the location words learning session, and 5.120 and 5.939 for the two groups after the clothing-related words learning session. The independent sample t-tests revealed a significant difference (

p < 0.05) between traditional learning methods and green screen-based learning for positional words, but not for clothing-related words (

p = 0.095).

In the delayed vocabulary test, similar patterns of improvement were observed: the mean scores of students in the control group (Mean = 3.680, SD = 1.725 for location words; Mean = 3.760, SD = 1.832 for clothes vocabulary) were lower than those in the experimental group (Mean = 4.697, SD = 1.667 for location words; Mean = 3.970, SD = 1.776 for clothes vocabulary), with significant differences for location words, but not for clothing-related words. The results suggest that the long-term memory of positional words is significantly enhanced when they are learned with the assistance of VB.

4.3. Learning Satisfaction

The results of the five-point Likert-scale questionnaire are summarized in

Table 7. In general, students demonstrated a positive attitude towards the use of green screen technology. The majority of the students believed that the use of green screen technology provided a high degree of authenticity and immersion. In the semi-structured interviews, all the interviewees used the terms “immersive”, “authentic” or “real-life situations” when describing their learning experience. For example, S1 mentioned:

In addition, S3 highlighted how the green screen technology enriched his learning experience through the teacher’s movements in the immersive background:

- 2.

“Watching you (the teacher) move around in the immersive background made the lessons more engaging and easier to understand. I felt like that I was actually in the places in question, which made the vocabulary and concepts stick in my mind much better”.

Due to the immersive nature of the technology, most students perceived a significant improvement in their cognitive process, especially in terms of memory retention (Mean = 4.212) and understanding of the learning content (Mean = 4.303). In his interview, S2 stated:

- 4.

“Beyond the mechanical methods of reading, writing, memorizing, and doing ordinary exercises, VB introduces a way of memorizing through visual and physical experiences, which is both innovative and interesting”.

Some interviewees also pointed out that the deeper impression of the vocabulary is attributed to the fact that the technology makes the language application scenarios more vivid. For example, S1 mentioned:

- 5.

“It makes cultural and practical scenarios more vivid, allowing me to have a deeper impression of the use of relevant grammar and vocabulary”.

Nevertheless, compared to the positive cognitive effects in terms of memory and understanding, VB seems to be less effective in helping students stay undistracted while studying French vocabulary (Mean = 3.939). The lower mean score may be explained by the fact that, according to S4, the current green screen technology may sometimes display image distortion in scene perception:

- 6.

“Sometimes, the green screen technology may exhibit a certain degree of distortion in scene reconstruction, which makes me feel disoriented when characters interact with the green screen environment”.

Table 7 also indicates that students recognized the positive impact of green screen technology on their motivation to learn French (Mean = 4.364). Most interviewees believed that green screen-based learning was perceived to be more engaging and more attractive compared to the traditional model of teaching. For instance, S1 remarked:

- 7.

“It (Green screen technology) breaks the traditional model of teaching where the teacher lectures in front of the classroom, bringing into play the subjective initiative of students, making the classroom atmosphere more relaxed and fun”.

S4 also noted that the use of VB promoted students’ learning interests in French culture and language:

- 8.

“The green screen scenes also gave me a more intuitive aperçu of various places in France, which further stimulated my interest in discovering French culture and studying the French language”.

Although most learners experienced positive emotions during the learning process, a few participants mentioned the frustration associated with the application of green screen technology in vocabulary learning. S2 mentioned the challenge of using digital technology and the resistance that it may generate:

- 9.

“Compared to traditional learning methods, green screen technology primarily uses digital manipulation, which might cause some students to feel resistant when using it”.

Finally, students generally agreed that VB provided a learning environment that encouraged interaction and exploration. For example, S5 commented:

- 10.

“We can virtually transport ourselves to different settings where the vocabulary is used. This approach allows us to follow the teacher’s actions and encourages us to ask questions, making the learning process much more dynamic and interactive”.

As suggested by S5, the green screen-based learning facilitated the willingness to speak and explore their ability in French.

In conclusion, the integration of green screen technology in vocabulary learning not only enhances students’ immediate and long-term retention of vocabulary but also positively influences their learning satisfaction and overall engagement in the learning process.

5. Discussion

By analyzing the results of the learning satisfaction questionnaire and the interviews, it was observed that VB, like other immersive technologies, can also facilitate vocabulary acquisition by providing an immersive and authentic context, enabling students to understand how to use the words in real-life situations. Compared to traditional language learning activities, “using a green screen can make the classroom more life-oriented and let us know how to express ourselves in daily life scenarios” (S5). With this advantage, students increased their exposure to the target language and had the chance to understand the practical value of the language in their specific contexts, which can help overcome the two major obstacles to fostering motivation among LOTE learners (cf. 1. Introduction) and thus maintain their motivation and engagement in learning. Another reason for the increase in students’ motivation and emotional engagement may be the “novelty” of the learning experience with the green screen technology to promote students’ curiosity, as S1 noted in his interview, “learning through green screen technology brought an exciting new dimension to me that I haven’t experienced before, which greatly captivated my interest and enriched the material of learning”. In addition, differing from traditional language learning methods, the application of VB enhanced students’ interaction and exploration. The ability for students to see the teacher’s real-time location in a virtual environment, to describe scenarios, to request movements or even to move inside the virtual space themselves adds a dynamic and interactive element to the learning experience and promotes the use of the target language. This interaction is not only engaging but also encourages active participation, as students can directly influence the lesson flow. Ultimately, green screen-based learning is found to aid cognitive processes and improve understanding, which improves students’ learning performance.

Through the vocabulary tests, it was found that green screen-based learning improves the immediate learning and long-term retention of French vocabulary: the mean scores of participants were higher in the experimental group than those in the control group. While the green screen technology significantly enhanced the retention of location words, the results were not significant for clothing-related words, in both the in-class and the delayed vocabulary tests. Therefore, these findings suggested that the effectiveness of green screen technology in vocabulary teaching may be particularly pronounced for certain categories of words, underscoring the importance of considering the type of vocabulary being taught when integrating visual technologies into language learning. The reason for the superiority of green screen technology in enhancing the retention of location-related words could be attributable to the visual contexts it provides, making abstract concepts more concrete and memorable. Given that location-related words often abstractly convey a sense of place without tangible references, their retention is notably enhanced by the contextual visualization provided by green screen technology; conversely, clothing-related words, which are inherently concrete and directly linked to tangible items, may not experience the same level of benefit from such visual aids.

These observations are further supported by theoretical and empirical evidence from previous studies on the application of dual coding theory. By reviewing a number of studies on the use of pictures in learning sight vocabulary (i.e., vocabulary that a reader can recognize instantly, without grapheme-phoneme analysis) and the impact of word concreteness and context, Sadoski [

22] suggests that nonverbal (i.e., pictorial) and verbal contexts and concreteness may play a more critical role in learning sight words than previously thought, and a balanced approach to sight vocabulary programs should incorporate decodability, concreteness, and context. Many empirical studies [

23,

24,

25] investigated the dual coding theory by examining the notable differences between concrete and abstract words. In the study of Yui et al. [

25], 298 participants were divided into two groups to memorize and recall lists of abstract or concrete words. Results supported the hypothesis that concrete words are recalled better than abstract ones. Shen [

26] compared the learning effects of two instructional methods used in Chinese vocabulary acquisition for both abstract and concrete words: one method involved only verbal encoding and another combined verbal with imagery encoding. Results indicate that combining verbal and imagery encoding does not significantly enhance the retention of concrete words over verbal encoding alone. For abstract words, however, the combined method significantly improves their retention. According to Shen [

26], this difference may be due to the fact that when learning concrete words, students inherently recall mental images of these words from their memory, even without visual aids. For abstract words, the mental images were not easily recalled, and the visual images used in imagery encoding significantly improved their retention. In the present study, it is possible that the mental images could not be readily retrieved without visual aids when students learned location-related words. Therefore, the use of green screen technology can significantly enhance the learning process by providing a visual context, which helps in forming stronger mental associations, potentially improving memory retention and understanding of these words.

As a pilot study, further investigation needs to be conducted to understand the effectiveness of VB for learning abstract and concrete words. Meanwhile, relevant studies can be envisaged to compare the impact of VB on language acquisition and retention with other immersive technologies. As S3 noted in his interview, “the learning experience might be even better if VR devices could be incorporated”. VR might prove to be more effective due to its fully immersive characteristics through visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning. However, it should be noted that green screen technology can already offer promising improvements in vocabulary learning outcomes and be easily implemented with current software like Zoom (5.2.0 or higher) and Tencent Meeting (1.3.0 or higher). In contrast, the high cost of VR equipment, if used solely for enhancing vocabulary teaching effectiveness, may not present a favorable cost–benefit ratio. In addition, the configuration of VB is often simpler than VR, requiring less specialized equipment and software. In terms of vocabulary learning, VB allows for a variety of immersive contexts to be created quickly with minimal effort, providing a flexible learning environment that can be tailored to different vocabulary topics. With its flexibility, accessibility, and cost-effective nature, green screen technology is likely to emerge as a practical solution for educators seeking to innovate vocabulary teaching strategies, by offering dynamic, interactive, immersive, and motivation-boosting learning experiences.

6. Conclusions

This present study aimed to analyze the impact of the integration of green screen technology for vocabulary acquisition within LOTE teaching, more specifically for Chinese students learning French as a second foreign language. According to the results, this technology is effective in promoting learners’ vocabulary acquisition (including both short-term and long-term retention), by offering students a positive and engaging learning experience. VB creates an authentic and immersive learning context that promotes increased interaction and active exploration, which are beneficial for vocabulary acquisition. Despite some potential limitations in green screen-based vocabulary learning, such as the occasional presence of a certain degree of distortion, it can still stimulate students’ motivation and participation, aid in consolidating knowledge, and reinforce language skills, helping students better understand and remember the content of learning.

The results also indicate that green screen technology is particularly effective in teaching location words because it offers visual context for these words whose mental images cannot be easily retrieved compared to concrete words with more tangible references. The application of VB transforms abstract location concepts into concrete, memorable experiences, which can significantly facilitate vocabulary retention and understanding. Green screen environments provide visual support that allows students to form stronger mental associations with location words, enhancing their ability to recall and apply the vocabulary in real-life contexts. This aligns with findings from previous studies on the application of dual coding theory, which underscores the importance of visual context and concreteness in vocabulary acquisition.

As the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of using VB for vocabulary learning, this study demonstrates that, like other immersive technologies applied in education, green screen technology can also play an important role in the improvement of learning motivation and outcomes. It should be acknowledged that, as a cost-effective and accessible tool, this technology has a high potential to enrich vocabulary learning and offer dynamic and interactive learning experiences that bridge the gap between language acquisition and real-world application.