Abstract

This longitudinal qualitative inquiry delves into the experiences of three novice teachers in the United States. Over the first four years of their teaching career, participants were interviewed multiple times, during which they created artifacts to capture the complex and emotional aspects of their experiences. The researchers utilized thematic analysis and restorying to illuminate the participants’ professional identity development and career trajectories. The findings underscore the realities of entering the teaching profession during a global teacher shortage and the tensions and vulnerability inherent in teacher identity development. The insights gleaned from these novice teachers provide fresh perspectives for educators, policymakers, and teacher educators to reimagine support systems to better sustain teachers in the profession.

1. Introduction

Supporting novice teachers during their induction period is vital to sustaining and retaining them in the teaching profession [1]. As our work shows, despite evidence of the benefits of quality mentoring and induction programs, too many novice teachers are left to their own devices during this important time in their teacher identity development. This can lead them to question their career trajectory and negatively impact their professional and personal well-being. When teacher attrition outpaces new teacher hires, it can negatively impact student learning and the financial health of a school district [2,3].

The purpose of this qualitative study was to investigate the experiences of novice teachers. Furthermore, recognizing that the United States is currently experiencing a teacher shortage, we sought to carefully examine the mentoring and induction experiences of three beginning teachers to glean insights to reimagine better support systems to sustain teachers in the profession. The three participants in this study are part of the uniquely challenged cohort who started their first year of teaching under unprecedented circumstances during the COVID pandemic.

2. Literature Review

This research aims to contribute to the body of literature related to supporting novice teachers to stay in the profession. In this review of the literature, we consider teacher identity development, stressors in education, teacher retention, and mentoring and induction.

2.1. Teacher Identity Development

Extensive research underscores the critical nature of identity development during the journey to becoming a teacher ([4,5,6,7], and many others). Britzman [4] asserts that adopting a teacher identity is an ongoing social negotiation, continually shaped by contextual and historical constraints.

Professional identity development extends across a teacher’s career, with an emphasis on the initial years. The first three to five years are widely recognized as challenging and pivotal, often termed the survival stage. These first years have been shown to significantly impact subsequent professional trajectories. In their seminal work, Feiman-Nemser [8] stated, “The first years of teaching are an intense and formative time in learning to teach, influencing not only whether people remain in teaching but what kind of teacher they become” (p. 1026). Shellings et al. [9] stated, “Through including identity work in induction programmes beginning teachers receive support at (identity) issues that are relevant in their current and future functioning” (p. 391). Similarly, in a study of Chilean novice teachers, researchers identified the need to support novice teachers in developing “emotional tools to stay in the profession” [10]. Both studies highlight the need for identity development among novice teachers to enhance their professionalism and career trajectories.

New teachers, because of their novice status, may inadvertently conform to the school norms of pedagogical practice [11]. School and district policies, accountability measures, and the school context often overshadow what they learned in their teacher preparation programs. The disparity between their ideals and the vision they had for themselves as teachers and the realities they experience can lead to frustration and a sense of helplessness unless they actively bridge the divide.

2.2. Stressors in Education

Becoming a teacher is a complex and often difficult process. Teaching is challenging, especially for teachers new to the profession [12]. New teachers encounter issues that are layered and complicated and continue to change as they move through their careers [8,12]. It has been well established that novice teachers are particularly vulnerable during the beginning of their careers, specifically within the first three to five years [13,14,15]. Historically, classroom management [16], differentiating instruction, and developing curriculum [16,17,18] were reported as just some of the stressors novice teachers experienced. Another qualitative study [18] reported novice teachers “feeling frustrated and exhausted by the many demands placed on them while they were still learning to teach (p. 194)”. The participants in this study were among the teachers who were confronted by unique stumbling blocks related to protocols put in place during the COVID pandemic, such as integrating new technological tools into their teaching practice [19]. The added COVID pandemic-related stressors intensified challenges related to well-being [14,20,21,22].

A lack of adequate guidance for novice teachers can result in increased levels of personal and professional distress [14]. The National Education Association reported that over 90 percent of members felt burnt out because of high levels of work-related stress [23]. Simos [24] also found that isolation at work contributed to teacher attrition. This isolation can happen when teachers work alone in a classroom, especially when they do not have sufficient opportunities for support from colleagues, co-teaching with colleagues, or lesson planning with colleagues [25,26]. The confluence of these long-standing and unprecedented challenges for teachers at the beginning of their careers can negatively impact their well-being, which can also impact their career trajectories.

2.3. Teacher Retention

The importance of retaining teachers in the profession cannot be overstated, particularly during a global teacher shortage. Decades of research show that teacher turnover negatively impacts student learning and has substantial financial consequences for school districts [2,3]. The data demonstrate the need to retain teachers in the profession. Researchers have identified the negative impact of teacher attrition on student achievement [27,28], particularly in schools with “large populations of Black and underperforming students” [29]. Ronfeldt et al. found that teacher turnover impacts all students in the school, not just those in the classrooms where teachers leave the school or the profession. While exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, the current teacher shortage has been developing for years, with ever-increasing gaps between openings and hires [30]. Research shows that these gaps are largely due to educators quitting the profession, even more than retirements, layoffs, or discharges [30]. Research suggests the need for further study into novice teachers’ experiences with mentoring and induction programs using longitudinal, qualitative methods to understand this phenomenon more fully [31,32]. Specifically, Billingsley and Bettini [33] suggest the need for further investigation into teachers’ decisions to remain in or leave the profession and the factors impacting those decisions.

2.4. Mentoring and Induction

Quality mentoring and induction programs have been shown to increase teacher retention [1] and can take many forms [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Kardos and Johnson [26] note that effective mentoring is a stabilizing mechanism that helps novice teachers gain their footing. Chaney et al. [35] found that novice teachers benefitted from monthly support. This support included working with their mentor, meeting other teachers, writing lesson plans together, and getting support in understanding the school’s pedagogical initiatives [35,36,37]. Similarly, Linton and Grant [38] reported that supportive conversations can help to improve teaching practices and promote self-reflection. When novice teachers are allowed to share their experiences and difficulties with other teachers, they advocate for their professional growth [39].

The European Commission [40] found that novice teachers displayed higher levels of pedagogical and professional identity development when involved in quality induction and mentoring programs. For example, increased critical thinking skills have been attributed to high-quality induction programs, affecting novice teachers’ attitudes and ideologies later in their careers [8]. In high-quality induction and mentoring programs, the goal is to support novice teachers’ personal as well as professional well-being. In some cases, it also reduces negative emotions and dissatisfaction [12,41,42,43]. Finally, high-quality programs provide novice teachers with multiple affordances, including teacher retention, which has been shown to improve both teacher and student well-being and performance [1,8].

Investment in educator development can aid in the alignment of novice teachers’ needs with professional training and create more collaborative work environments [44]. However, many states do not require mentoring and induction programs. The Education Commission of the States [45] found that 31 states mandated mentoring and/or induction programs for novice teachers. Ten of those states’ programs only provided support for a novice teacher’s first year in the profession, while ten other states’ programs provided support during a novice teacher’s first and second years [42]. This report affirms Darling-Hammond and Hyler’s [44] call to require school districts to prioritize the needs of educators during their induction periods. Internationally, countries such as Germany, China, and New Zealand offer mandatory induction programs that include supports such as assigned mentors, teaching observations, collaboration with colleagues, and reduced workload, which are shown to effectively support novice teachers [46].

Where mentorship programs exist in schools, teachers are typically assigned a single mentor to guide them through their induction period. However, Kram [47] found that “individuals rely upon not just one [mentor] but multiple for developmental support in their careers” ([47], p. 264). Higgins and Kram [48] found that mentees with a constellation of mentors were successful in their chosen careers, highlighting that the mentees’ advancement was “tied to an individual’s engagement” with more than one mentor, as opposed to a single mentor (p. 238).

The concept of mentoring constellations is also present in education. Felten and Lambert [49] posit that universities must commit resources to assist undergraduate students to “develop the capacity to build constellations of mentors” (p. 149). Felten and Lambert [49] contend that the key is not tasking each student with identifying a single mentor who will meet all their needs, but rather creating a relationship-rich environment where students will have frequent opportunities to connect with many peers, faculty, staff, and others on and off campus (p. 6).

Felten and Lambert [49] acknowledge that one-on-one mentoring is powerful but comes with challenges, including a lack of personnel and a high monetary cost. Johnson et al. [4] also contend that those new to a profession should be intentional as they build their constellation of mentors and diversify the constellation membership and choose mentors with whom they have strong relationships.

3. Research Methodology

We, teacher educators in three different teacher preparation programs, became concerned about the experiences of our recent graduates who were beginning their teaching careers. This was the impetus for this longitudinal, qualitative study. We wanted to know how novice teachers were being supported (or not) in their early years of teaching. Although we did not anticipate following a cohort of teachers who were student teaching during the beginning of a pandemic, this was the timing of our study.

3.1. Context and Participants

This article focuses on three early-career teachers who were selected because of their varying career trajectories—two of the teachers shifted grade levels or moved districts, and one left the teaching profession altogether. Mirroring typical teacher preparation statistics, our three participants were white, middle-class females whose first language was English and who were in their early 20s. Like student teachers around the world in the spring of 2020, Kathleen, Bailey, and Lindsay’s student teaching experience was interrupted by the global pandemic. Kathleen had a full-year student teaching experience, which began in the fall of 2019. She recalled taking over her placement room in November 2019 as one of her biggest successes. Bailey experienced an abrupt end to her 16-week student teaching assignment, which took a toll both professionally and personally. She described her last day of in-person school in her student teaching placement as tearful and unsettling. Although Lindsay found most of her classroom practicum experiences during her teacher preparation to be quite critical to her learning-to-teach journey, student teaching was less idyllic. During that semester-long experience, she “felt like [she] was all by [her]self” and like she “didn’t have a mentor”. Due to the lack of support from her mentor teacher, she had to switch classroom placements to ensure she got the support she needed. While her second student teaching placement was with a “really passionate teacher” who was able to “help her understand what all went into teaching” and all the necessary preparation, this switch happened just “two weeks before things got shut down” due to the COVID pandemic. This did not leave much time for Lindsay to have a supportive student teaching experience.

3.2. Researcher Positionality

Lowenstein [50] points out that many teacher preparation programs in the United States are led by white, lower-middle-class professors without much experience in urban teaching, and they train mostly white, lower-middle-class female students. While our research team is made up of three white female professors teaching mostly white female students, we have a combined 25 years of experience teaching in diverse K-6 schools. Additionally, we have served as liaisons in university partnership schools, taught literacy courses, and supervised student teachers in urban, rural, and high-need schools. Bailey, Kathleen, and Lindsay were students from our universities, and at the time of recruitment, they were preparing for student teaching but were not enrolled in any of our classes. To ensure that they felt comfortable answering freely, a graduate assistant conducted all the interviews.

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected under an Institutional Review Board-approved exempt protocol. Data collection began at the start of the student teaching semester. In this article, we focus on two semi-structured interviews (see Appendix A), one at the end of the first year of teaching and the other at the two-and-a-half-year mark. These interviews were chosen for their retrospective questions and activities, which helped participants identify critical incidents impacting their identity development and career trajectories.

3.4. Data Analysis

For this study, we analyzed the two selected interview transcripts. The questions guiding our research were:

- How do novice teachers experience their first years of teaching?

- ○

- What impact do their experiences have on their professional identity development?

- ○

- What role does mentoring play in their first year of teaching?

Qualitative data analysis began during data collection, with our graduate assistant transcribing interviews and providing analytic memos. The research team iteratively read the data and performed initial coding, organizing it around topics discussed by the novice teachers. For example, mentoring, personal well-being, and concerns about students’ well-being were initial codes in Kathleen’s teaching story. A topic was considered a theme if a teacher discussed it at length or across multiple interviews.

The goal of these initial codes was to “restory” [51] the novice teachers’ narratives, making the complexities of their experiences visible. After coding each transcript, we refined the codes to accurately represent each teacher’s story. We re-read data chunks for each code and utilized in vivo coding, described by Marshall and Rossman [52], as using participants’ own words as codes. For example, Kathleen’s in vivo theme of “It’s Fine; You Can Figure It Out” is represented by “Seeking Mentorship” in the Findings section. We incorporated important information and included as many direct quotes as possible. Each teacher’s “restoried” narrative was then analyzed to understand their early teaching experiences. We created a storyline for each teacher’s experiences, serving as a backdrop for interpretation and identifying the most salient themes for the final section of each story.

We ensured trustworthiness through prolonged engagement, peer debriefing, and member checking [49]. Prolonged engagement involved conducting 30–60-minute interviews with all three teachers multiple times per year. As a research team, we repeatedly reviewed each restoried narrative, providing input and highlighting the most salient themes. Each participant read their restoried narrative as a member check. They were asked to suggest any changes or deletions to ensure that we accurately represented their experiences.

4. Findings

The findings of this study are presented as three distinct restoried narratives: those of Kathleen, Bailey, and Lindsay. The narratives that follow begin with an introductory overview of each teacher’s experiences. The title of these introductory overviews were crafted by the participants during an interview when prompted to provide a title of what we called an “autobiography of their early career”. Subsequent sections for each teacher are then organized thematically. The titles for these subsections begin with themes and are followed by in vivo subtitles. Each story concludes with a final section that encapsulates the overarching theme of their early teaching journey.

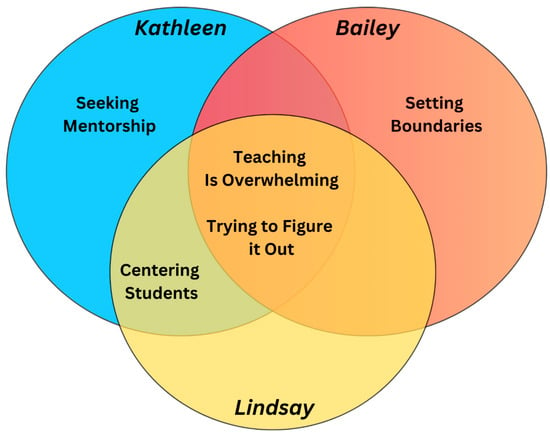

In Figure 1, each circle represents Kathleen, Bailey, and Lindsay, with overlapping areas showing common themes among them. Unique points related to Kathleen and Bailey are placed outside the overlapping sections. The overarching themes are Teaching Is Overwhelming, Centering Students, Trying to Figure It Out, Seeking Mentorship, and Setting Boundaries.

Figure 1.

Overlapping and distinct themes.

4.1. The Unpredictable Years: Kathleen’s Early Years in Teaching

Kathleen began her first year as a virtual teaching assistant and was hired in October as a second-grade virtual teacher. She stayed in the same district for her second year, transitioning to an in-person third-grade teacher, and continued into her third year as a fourth-grade teacher in the same building. When titling her early teaching autobiography, she elaborated, “The times when I think it’s going to go really well, it doesn’t always go well, and the times I think it’s not going to go well, it gets better”.

4.1.1. Teaching Is Overwhelming: “I’m Very Overwhelmed and I Want to Do This Well”

Kathleen’s first teaching assignment started with some confusion. She was transitioning from the role of teaching assistant to teaching full-time virtually. She thought she would be teaching first grade, but found out the day before school started that she would be teaching second grade. She remembered being “very vocal with the [administration]”. She sent an email stating, “I don’t have any of [the necessary] information. I’m very overwhelmed, and I want to do this well, but I don’t feel like I’m in a place where I can do this”.

Kathleen had 19 second-grade students in her virtual classroom, all in the same district but from three different elementary schools. She described her biggest challenges as technology barriers, time management, meeting the expectations of the district and parents, and trying to build a community in a virtual space. She was expected to teach every subject every day. She tried to do 15-minute mini-lessons with a morning meeting, reading, phonics, and writing in the morning and after lunch teaching math, science, and social studies. She also read aloud to her students at the end of each day. When deviating from her schedule, Kathleen was reminded, “Some kids don’t know how to tell time”, so they set alarms. But that was hard when each day was a little different, with all the alarms they had set. When trying to include activities to build community, “parents complained that we [didn’t] need to spend time doing this; we need[ed] to be doing curriculum”.

4.1.2. Centering Students: “Supporting Students and Helping Them through Things”

Students sent Kathleen daily chats in Zoom, expressing that they were feeling sad. When she asked why, they often said they did not know, but just felt sad. She found that “working through those big feelings [was] tough, especially because they [were] on screens all day. They look[ed] like little zombies”. Just like her students, Kathleen was sad “because there [was] nothing [she] could do to change that”.

Kathleen’s silver linings of year one included “finding new and creative ways to innovate instruction, virtually”. She enjoyed teaching her students technology skills and being able to “support [her] students and help them through things”. She fondly remembered her first year with “cool kids” that “solidified [her] feeling that [she] was capable of teaching, even though it was [in] a very challenging environment”.

Kathleen’s second year of teaching was her first in a physical classroom; she taught third grade. Not having a strong working relationship with her colleagues was one of the hardest parts of this year. Despite this, her relationships with her students were a highlight. She realized how “awesome” they were and how excited she was to “spend time with them”. Celebrating their growth, she “felt more confident as a teacher” by the end of the school year. She was proud that she “made it through [her] first in-person year” and completed her master’s degree in elementary education.

4.1.3. Trying to Figure It Out: “Am I Supposed to Be Teaching or Am I Not?”

During her third year of teaching, Kathleen remained in the same school district with yet another grade level, fourth grade. Kathleen shared, “Year three has been interesting”. She argued that it was her hardest year because the students had been the most challenging. She attributed her struggles to the “behavioral issues” of her students and navigating “all the little pieces of that” [getting them support]. She had been getting up early and staying up late and was “exhausted” and “couldn’t function” when she got home. Her “mentality about teaching had been kind of negative” and had her wondering, “Am I supposed to be teaching or am I not?” In contrast, Kathleen was gaining confidence in her decision-making ability as she worked “making instructional decisions that [were] directly responsive to [her] kids and not listening to the other voices”.

4.1.4. Seeking Mentorship: “It’s Fine; You Can Figure It Out”

When asked what resources she wished were available, Kathleen suggested she would have liked “a bank of questions for admin, or mentors in general on what to ask a new teacher and to best support them”. In her experience, she “really felt like a lot of times, people would just talk to her like they knew what she needed”, and “it ended up being not helpful”. She added that it would have been nice if someone had asked her what she needed, but even then, she recalled that there were times she would not have been sure how to answer that question. In hindsight, she wished there “was a consistent check-in with someone”. In Kathleen’s experience, she tried to schedule weekly mentor meetings herself, and “after literally meeting one time” the meetings stopped, and she “didn’t feel comfortable continuing to instigate that because [her] mentor probably [had] a lot on her plate”. Kathleen realized that her mentor was doing a lot, and she did not “want to annoy her”. However, she also was frustrated, stating, “At the same time, I didn’t feel like I should have been the one having to constantly reach out and it was hard for me…and so I constantly just talked myself out of [reaching out]”. She was telling herself, “You don’t need to reach out it’s fine, you can figure it out”.

4.2. The Quest for Collaboration and Mentorship

During Kathleen’s initial years as an educator, she yearned for collaboration and mentorship. This quest for mentorship and collaboration was a recurring theme. Kathleen often felt unsupported by the administration and had to seek mentorship on her own. Her third year showed improvement in peer support and collaboration, which was critical to her sense of belonging and effectiveness.

Kathleen’s first year was filled with challenges as she sought support. She asked many questions, expecting the principal to be a major supporter, but found the principal “not very supportive”. This led to her “mental breaking point”. Often, she felt spoken to as if she were a veteran teacher rather than a novice and had to “either figure it out on [her] own or reach out to someone else”.

Typically, first-year teachers were assigned mentors, but Kathleen “took it upon herself” to seek mentors through her father, a teaching assistant at an elementary school. Her experience with peer support was mixed: “People that [she] would expect to be [supportive] were not, and the people she reached out to [were]”. Eventually, her principal asked if she wanted a mentor. Although Kathleen’s initial thought was, “That would have been a great question in October when I started out”, she was eventually connected with another second-grade teacher who became her “MVP”. Kathleen also found that “communication was one of the most challenging parts of this job, in terms of what you get versus what you give to others”.

During her second year, Kathleen realized that collaboration with her peers was key to her success and felt that not having this was one of the hardest parts of her second year as a teacher. In contrast, during her third year, she felt better about the support from her team, as they were all working together to figure things out. She still remembered in year two that she felt her teaching team was not “really together”, but felt “very island-like”. She appreciated that in year three, she and her peers “might be in the same sinking ship but [were] keeping each other afloat”.

Kathleen’s teaching journey, marked by challenges and personal growth, highlights the demanding path of a beginning teacher. From grappling with technology, student support, and time management in a virtual classroom to finding her footing and confidence in an in-person setting, Kathleen was overwhelmed but gained confidence as she sought the mentorship she craved.

Transitioning from Kathleen’s experiences, we now turn to Bailey’s story. Bailey faced her own set of challenges and sought the support needed to navigate the early stages of her teaching career. Her journey, like Kathleen’s, emphasizes the importance of mentorship, collaboration, and improvement in teaching.

4.3. Bailey’s Life Preservers for Teaching

Starting her teaching career in August 2020 during a global pandemic, and after an incomplete student teaching semester, Bailey faced challenges. She continued in the same district for her second year, again teaching second grade. By her third year, in search of better support, she had moved to a neighboring district to teach third grade. Bailey pointed out that “sometimes teachers are left to sink or swim…but there are life preservers around, and we need more of them. Teachers shouldn’t sink”.

4.3.1. Teaching Is Overwhelming: “It’s like a Lighthouse with No Light”

When reflecting on the support she received during her first year of teaching, Bailey described that experience as “a lighthouse with no light”. She went on:

“You’re trying to look for the path…and then there’s no light. You get glimpses of it, but then it’s already past us. Sometimes it comes back around, but maybe it is broken sometimes. There is a little bit of support, but I want so much more”.

One of the most challenging parts was the start of her first school year. She said, “Everything was thrown at me”, and she spent a lot of time every day and “each weekend” and experienced a “lot of stress about setting up [her] classroom virtually and in person” while “not really knowing what [she] was doing”. The previous teacher had left a mess in the classroom, and she had trouble locating teachers’ manuals and figuring out how to use those she found. This was exacerbated by her admission that she struggles with “asking for help”. Particularly amid a global pandemic, she felt selfish “ask[ing] for help when everyone is going through…hell”.

During Bailey’s first year, she encountered challenges as she tried to find the “sweet spot” of instruction in which she held high academic expectations but “didn’t challenge them too much where they check[ed] out”. During her first year, she struggled to find her way teaching online. Bailey found it difficult to know which students needed additional support and differentiate instruction to meet everyone’s individual needs. Again, she reached out for support, this time from her instructional coach. She relied on data both to guide her instruction and to attempt to use it to motivate students by rewarding academic improvements.

Another challenge Bailey faced that many new teachers encounter is collaborating with parents, particularly many of whom she said put “a lot of pressure on [their children]”. Bailey described feeling pressure from parents in several ways. For instance, she said one of her second graders said her dad “gets angry when [she] doesn’t assign homework because he wants her to be a lawyer”. Another student, who received one point out of three possible points on an assignment, which Bailey said means “needs improvement”, was afraid to take his work home to show his mom because “she would take away [his] birthday present”. Navigating providing authentic and accurate feedback and the “pressure outside of [their] classroom to do well” while letting them know their “kids are doing great in this area” was a balancing act. She tackled some of this by implementing “growth mindset activities” and encouraging hard work and improvement over “perfect scores”.

Maintaining her well-being was another challenge during her first year. She described “waves of burnout and low confidence”. She took frequent long walks after school to try to “reset” before working more. She battled insomnia as she constantly thought about her students and how she could better support them. She went to school nearly every weekend to prepare for the following week.

4.3.2. Trying to Figure It Out: “There’s a Lot That Is Mindset but There’s Also a Lot That’s Your External Circumstances”

Bailey attributed much of her continued passion and optimism about the profession to her colleagues and the culture of the school. She described the environment as one that valued continued improvement and was “student focused”. She compared her own experience to that of her sister in a neighboring school district. During her visits there, she experienced a different environment in which teachers spoke negatively about the profession and their students. She said she got the feeling teachers were there to “do the bare minimum”. She was grateful to be in a much more positive place where everyone supported each other. She said, “Teachers have to decide to leave or stay in the profession” and “there is a lot that is mindset but there’s also a lot that’s your external circumstances”.

While she felt supported in general, her district-assigned mentor was not as accessible as she had hoped. She said they “[didn’t] talk that much”, although she could reach out to her if she needed to. Her mentor taught a different grade level and had a newborn, so she would leave immediately when the school day ended, while Bailey stayed to prepare. At the beginning of the year, her mentor checked in more frequently but towards the end would just ask Bailey how her day was going rather than providing structured mentorship support. Bailey was able to find other colleagues to support her, though. She said it “[made] more sense” to reach out to “other people who have more expertise and have been [teaching] longer”. She shared that she got to know her assistant principal and instructional coach well and that they “checked in” on her more than her mentor.

4.3.3. Setting Boundaries: “Work Smarter, Not Harder”

In her third year of teaching, Bailey moved to a different school district not far from her previous one to teach third grade. The move was prompted by her previous school beginning to feel somewhat “chaotic”. Her new school afforded her “more professional development opportunities” and a “more established” faculty. While the move was an adjustment at first and made her “feel like a first-year teacher all over again”, midway through her third year, she was settling in. She described her current experience level as “no longer a new teacher” but also “not the most experienced”. For instance, she saw more experienced teachers implementing instructional practices, such as small group rotations, and wanted to try them, but said that it “still feels really intimidating”. Even “easy” things such as putting students’ desks in groups of four, as she had always imagined doing, felt difficult after years of having students in rows due to COVID protocols. Overall, though, she felt she had “[fewer] challenges compared to years one and two”. Nevertheless, she still considered herself an inexperienced teacher.

During an interview, Bailey referred to studies in which “during the first five years, teachers may be the same with their level” and “half of them leave the profession”. Knowing that she is still in a rapid growth stage of her career comforted Bailey, as she felt “okay…with making mistakes”. Observing other teachers helped her see what was possible and areas for growth.

At her new school, in her third year, Bailey had not officially been assigned a mentor, although she did attend a new teacher orientation at the start of the year. Even so, she felt supported by “two teachers [on her grade-level team] who have 20 plus years [of experience]” and referred to them as her mentors, even though unofficially. This felt much more natural and supportive to Bailey than her mentorship during her first two years when “they had a whole different job” and “weren’t on her team”. Other colleagues, including her principal, were always willing to talk or provide support when needed.

In her third year, as she gained more experience, Bailey could pass on some of her wisdom to new teachers. She supported another third-year teacher with strategies to “work smarter, not harder” to keep closer to her contract hours by using checklists and other organizational strategies. This was an area in which she thought she had grown the most. It had been “a lot about letting go of control and feeling like you have to get everything done in a day”. Also, giving the students more responsibility in the classroom was helpful. For instance, Bailey said in her first two years she would “come in to sharpen pencils each day”, but now it was a classroom job. This tip, and others, improved Bailey’s work–life balance.

4.4. Seeking Validation and Fulfillment

Throughout the beginning of her teaching journey, Bailey consistently sought validation and fulfillment. She was a self-proclaimed overachiever and had always had the goal of being “an amazing teacher, like a top-tier teacher”. She looked up to her colleagues, particularly her assistant principal and instructional coach, during her first two years as “what [she] want[ed] to be”. She craved feedback, hoping for more observations of her teaching. She found it incredibly valuable to be able to observe her colleagues. She stated that when she observed, “it feels like your world just opens up more”, as she was able to see how others did things.

Overall, Bailey found teaching to be the profession for her. Even though the first years were challenging, she recognized that is likely why “this study is happening in the first place”—to learn more about the experiences of beginning teachers. While she “hate[d] how it felt like a rite of passage because [she didn’t] want that for anyone”, she acknowledged that “teaching is different than a lot of jobs”, and, in that way, “is very special”.

Shifting from Bailey’s experiences, we now transition to Lindsay’s story. We explore the hardships Lindsay faced in her early years of teaching as she made career decisions based on prioritizing taking care of herself. Her journey, like Bailey’s, emphasizes the role of personal mindset and external circumstances for early career teachers.

4.5. “You Never Know What Life Can Throw Your Way”: The Story of Lindsay’s Teaching Journey

In her first year, Lindsay taught fifth grade with a mixture of in-person and virtual instruction. The instructional modalities went back and forth as local authorities dictated due to the circumstances of the pandemic. In her second year, she was involuntarily moved to second grade. During her third year, she moved to another city and taught in a new district. Before mid-year, Lindsay resigned from this position. She explained, “You might be on a different path than what you originally thought…, but the journey doesn’t always have to be planned out to a T because it can always change”.

4.5.1. Centering Students: “Try to Pick Up All the Pieces”

Lindsay’s first school year as a fifth-grade teacher started as most during the fall semester of 2020 with virtual instruction. Her district decided to reopen in October, but that only lasted about a month before they were forced to close again due to increasing COVID cases. Starting the school year online, Lindsay experienced many of the same struggles as other teachers, including engagement and building relationships with students. Even though the return to in-person instruction was brief (about four weeks), this allowed time for her to get to know her students a little better. So, when they returned to virtual instruction again, “the participation and the engagement [was] much higher than it was”.

Teaching during a pandemic was physically and emotionally challenging for Lindsay, as it was for many teachers worldwide. When her students were in her classroom, she tried to focus on the social and emotional well-being of her students. She learned that many of them had “adult responsibilities”, such as “putting food on the table” and “taking care of siblings”, and she made sure to have “real conversations” about their concerns and fears. Many shared that they were “scared [of getting sick], but they were at school because their parents needed somewhere for them to go while they worked”.

4.5.2. Teaching Is Overwhelming: “You Can’t Control Everything”

During her first year, Lindsay had several mentors to support her learning. One was “another fifth-grade teacher” and the other was a “district mentor who [was] a retired teacher”. Her district mentor observed her teaching via Zoom, which was “a great way [to get] feedback that was non-evaluative”. Additionally, Lindsay had several observations by her principal. She found it “really, really good to have an observation”. Beyond her mentors and administrator, Lindsay also had the support of “two coaches in the building”, a math coach and a literacy coach, who were “extremely helpful”. In addition to this professional support, Lindsay’s parents also supported her and were “proud of everything she was doing [for her students]”. Lindsay’s friends, many of whom were also teachers, were “so supportive”, as well. Even halfway through her first year with all the support she had, Lindsay noted that she “still [felt] lost”, but felt that was normal and that it would “likely be like that for the first three to five years until [she] really feels like [she] knew how to do everything and could see things coming from a mile away”.

During Lindsay’s second year in the classroom, she moved from fifth grade to second grade in the same elementary school. This change was not her choice but rather was due to “staffing changes”, including “people leaving and early retirements”. While she said she was “voluntold” to go to second grade, she ended up enjoying the change.

One of her self-proclaimed life lessons she learned during her first year of teaching was, “you can’t control everything”. This manifested in many ways, including the repercussions of the pandemic and its impact on teaching and schooling in general. While she learned that she could not control everything, she took comfort in thinking she could “control what’s happening in [her] classroom during those eight hours”.

The biggest challenge she faced in her second year of teaching was the “difficult behaviors”. She saw this as a larger issue stemming from pandemic isolation that students had experienced. She said, “I don’t think it’s just my classroom. I don’t think it’s just our school. I think it’s…worldwide”. In her second-grade classroom, she shared that there were many “aggressive behaviors” and that “students [had] to be taken out of the classroom or suspended”. She attributed much of this to not only the isolation but also “the societal things they were experiencing”, as well as the increased consumption of social media trends, violent video games, and television shows.

4.5.3. Trying to Figure It Out: “But What Else Am I Going to Do?”

During the middle of Lindsay’s second year of teaching, she was already beginning to think about what the future might bring and if she would stay in the district or even the profession. She mentioned that “other colleagues who graduated with [her] from [her university] recently changed districts”. She stated, however, that “it’s not fair to give up on teaching when we don’t have a lot of experience outside of COVID”. However, she did question if “this is really what she had wanted to do since [she] was five years old”, but “[didn’t] really have a backup plan”. She lamented, “But what else am I going to do? It’s not fair”. While she “enjoy[ed] the teaching aspect”, and “enjoy[ed] working with students”, the parts she did not enjoy were “the disconnects between administration and districts and what other districts are doing”. She had been exploring “what other opportunities [were] out there for teachers and educators who [were] feeling this way”.

During the middle of her second year in the classroom, Lindsay thought a lot about the burnout she was feeling. She mentioned that during her teacher preparation, there was a frequent talk about burnout teachers can experience and that “if you make it past five years, you’re good”. At the time, she thought, “That’ll never happen to me…I want to do this forever”. But here she was experiencing it herself. She shared that if she knew then that she “was going to have to do all this and carry all this”, she “wouldn’t have chosen this path”. She followed several social media sites that showed what teachers could do with their skills besides teaching.

While things were challenging and frustrating, Lindsay was grateful to have a good support network in her grade-level team and “supportive administration”, as well as a behavior specialist, social worker, counselor, and psychiatrist. She found it “reassuring to know [she] had professional support”. She also prioritized taking care of herself. She noted that this was emphasized in her teacher preparation program and by family and friends to “dedicate time to your personal life”. While she sometimes “felt guilty” about doing this, it allowed her to be “energized” and “motivated”. After being “touched and screamed at and having [her] name called a bajillion times a day”, she noted that sometimes she “just needed to be by [herself]” and recognized that was “okay”.

4.6. Taking a Break from Education

Before the start of Lindsay’s third year, she moved to a different city and began teaching in a new district. She stated that even two and a half years into her career, she “still [felt] like a first-year teacher” since she “never really got a good groove going”. Her new school had “a lot of issues”, including “safety concerns” and “how the administration was running things”, along with difficult behaviors in the classroom.

She did not have a mentor assigned to her that year; however, there was a “new teacher program”. The meetings that constituted the program were about topics such as “how to set up your classroom” and “how to communicate with parents”. She “did not find a lot of benefit” from the program. She noted that it would have been helpful for “actual new teachers”, but everyone new to the district participated in the same program, regardless of their teaching experience elsewhere. She had support from her grade-level team, the social worker, the principal, and the assistant principal. She confided in them about her frustration and struggles, and they would “come in and do extra observations in [her] classroom”, as she had requested. She valued their advice as she “didn’t want to give up”. Nevertheless, halfway through the year, Lindsay decided to resign and “take a break from education”.

While she had challenges in her new setting, it was not just the school that caused her to leave; it was education in general and wanting a different pace. She noted that “in the corporate world…you could take a mental health day or just take the day off no questions about it. You just click a little button that says you’ll be out of the office”. She went on, “As educators, there is so much pressure, and it’s a guilty thing, because there’s so much more work to do being out of the office than just showing up and just doing it”. She needed to take care of herself and did not think that was possible in her current profession. And she felt she needed to resign in the middle of the year because “if [she] were to [finish] out the year, [she] would just be broken”.

A lack of support and resources, unattainable expectations, and “kid behavior”, all contributed to Lindsay’s decision to leave the teaching profession. She encouraged other educators to think about what they needed and to “take a leap of faith and go find a place where you do feel comfortable”. When reflecting on her recent decision to leave teaching, she said, “I don’t feel like I gave up on the kids. I feel like if I would have stayed, I would have given up on myself”.

5. Discussion

The individual and collective narratives of the experiences of these beginning teachers underscore the realities of entering the teaching profession today, in the wake of a global pandemic and amid a teacher shortage, including the tensions and vulnerability inherent in teacher identity development. The insights gleaned from these novice teachers provide fresh perspectives for educators, policymakers, and teacher and administrator educators to reimagine support systems to better sustain teachers in the profession.

5.1. Impact of School Context

Throughout the experiences of all three novice teachers, evidenced by the theme “trying to figure it out”, their school context deeply impacted their sense of well-being and, ultimately, their decision to stay or leave the profession. As Bailey described, “Sometimes it’s your mindset, and sometimes it’s your external circumstances that impact whether you stay or leave”. In Bailey’s story, for example, she moved school districts when things started to feel “chaotic”. Lindsay was deeply affected by the context of the schools in which she taught. She attributed “a lot of issues”, “safety concerns”, and administrative and behavioral challenges as contributing to her eventual departure from the profession.

5.2. Impact of Student Behavior and Emotions Related to the COVID Pandemic

Students’ behaviors and emotions related to the COVID pandemic had a profound impact on the novice teachers’ experiences and well-being during their first years. During remote teaching, they struggled with engaging students. They frequently noted how “sad” and “scared” their students appeared. It was difficult to build relationships with students and families through a screen, which impacted student behavior and the well-being of students and teachers alike. Hearing about the emotions and experiences their students were facing, such as helping with “adult responsibilities” and “fear of getting sick”, took an emotional toll on the teachers. This directly relates to the theme “centering students”, which was present in Kathleen, Bailey, and Lindsay’s early career experiences. They also felt additional pressure from the parents being placed on the students and teachers.

Once remote teaching ended, student behavior issues continued to challenge the new teachers. For instance, Lindsay felt that the pandemic isolation, societal turmoil, social media, and violence in media contributed to many of the “difficult” and “aggressive” behaviors she witnessed in her classroom. After she moved schools, further “safety concerns” influenced her decision to “take a break from education”.

5.3. Impact of (Lack of) Support

Throughout their first years, support was a critical factor in helping the teachers navigate the challenges they experienced, as evidenced in the “seeking mentorship” theme. Some received more support than others. Isolation during remote instruction was a common experience. It was challenging for them to seek support without being in the same physical space as their colleagues and mentors. Additionally, several teachers noted that they felt guilty for asking for help during a pandemic “when everyone was going through hell”. They experienced variable support from administrators. Some were “very supportive”, while others were “not supportive at all”. Kathleen even felt that her principal pushed her to her “mental breaking point”.

While all the novice teachers were eventually assigned mentors, they all sought out support from others on their own during their first three years in the profession. Even in instances in which it was not support or mentoring in the traditional sense, having colleagues they could collaborate with felt supportive. For instance, in her third year, Kathleen experienced a feeling of commiseration with her colleagues, as she described them being “in the same sinking ship but keeping each other afloat”.

5.4. Impact on Teacher Well-Being

The overall well-being of the novice teachers ebbed and flowed throughout their first three years in the classroom. Feelings of joy and contentment were followed by waves of burnout, low confidence, and exhaustion. Kathleen “couldn’t function when [she] got home”. Bailey battled insomnia as she worried about her students and took many long walks to de-stress. Eventually, she adopted the attitude of “working smarter, not harder”, which positively impacted her sense of well-being as she let go of some of the pressure she placed on herself. Lindsay, too, decided to let go of what she could not control and prioritized taking care of herself, which helped her feel more “energized” and “motivated”. Their sense of well-being, as evidenced in the “setting boundaries” theme, influenced their thoughts about the profession and whether it was one they wanted to continue to pursue.

5.5. Impact of Experiences on Career Trajectories

All three teachers encountered the theme “teaching is overwhelming” and, as a result, considered leaving the profession at some point. During her third year, Kathleen had negative feelings about teaching and seriously considered whether she would or could continue. In the end, she stayed and felt comfort in commiseration with her colleagues and a sense of inspiration by pursuing her master’s degree.

When leaving the teaching profession crossed Bailey’s mind, she did not give it much consideration. She did, however, decide to move schools when her previous one started to feel “chaotic”. Her new school felt “more established” and provided her with more opportunities for professional development. She knew that the first few years of teaching were challenging for most teachers and that it was okay she did not yet know everything. She took great comfort in knowing that she was supposed to be growing and learning. This contributed to her decision to remain in the profession, as she wanted to be an “excellent” teacher and her new school was affording her the opportunities to continue to grow professionally.

Lindsay felt intense burnout in year two, which caused her to question whether she wanted to continue to teach. She felt conflicted, as it was “what [she] had always wanted to do”. Still, she frequently questioned her decision to be a teacher. When she changed districts at the beginning of year three, she hoped that things would improve. Instead, her feelings of doubt about her choice of profession intensified. In the end, she decided she needed a “different pace” as the pressure and guilt got to her. She left the teaching profession in the middle of the third year as she felt that if she finished her third year, she “would just be broken”.

5.6. Relation to Existing Research

Mentoring matters and quality induction support can lead to increased teacher retention. Kukla-Acevedo [32] reported that novice teachers were nearly one and a half times as likely to leave teaching and more than twice as likely to switch schools as experienced teachers (<five years). Much of the current literature on teacher mentoring is based on the experiences of mentors [53,54,55] and descriptions of mentoring programs [56]. Novice teachers’ voices, however, are too often absent from the discourse. This study aimed to amplify their voices so that we could learn from their experiences.

As was evident in the theme “trying to figure it out” present in each novice teachers’ experiences, the school context can greatly impact their experiences and pedagogical practice. As Bressman et al. [11] note, new teachers often conform to school norms due to their novice status, which can cause frustration and lack of agency as they “try to figure it out”. Further, student behaviors and emotions related to COVID caused Kathleen and Lindsay to “center students”. While novice teachers have historically experienced stressors related to classroom management [16], this was exacerbated for this group of teachers, as the stressors from the COVID pandemic magnified the difficulties related to well-being [14,20,21,22]. The theme of “setting boundaries”, most prevalent in Bailey’s story as she decided to “work smarter, not harder” and let go of expectations of perfection, aligns with the literature on teacher well-being. Setting boundaries allowed her to combat some of the work-related stress that most teachers experience [23].

While all teachers in the study sought support to some degree, “seeking mentorship” was most prevalent in Kathleen’s story. As evidenced in the literature, this mentorship she was seeking can support novice teachers as they gain their footing [26], increase pedagogical and professional identity development [40], and increase well-being [12,41,42,43]. Overall, this support, which was received by some novice teachers but not all, can greatly influence the feeling that “teaching is overwhelming”, a theme common across all stories. The feeling of being overwhelmed can impact career trajectories and retention in the profession. In this time of global teacher shortage [30], listening to the voices of novice teachers about their experiences with support and decisions to leave or remain in the field is crucial [31,32,33].

6. Conclusions and Implications

While the literature on beneficial mentoring is robust, these practices are not always implemented with fidelity in schools, as is evidenced by the narratives of Kathleen, Bailey, and Lindsay. We aim to provide practical suggestions for mentoring novice teachers. In this conclusion, we discuss ways school administrators can support novice teachers, specifically through co-designing mentoring resources and differentiating the support needed for novice teachers. Next, we emphasize the affordances of mentoring constellations and effective mentoring practices.

6.1. School Administrators’ Support of Novice Teachers

While teaching and supporting novice teachers to build constellations of mentors and advocating for themselves is beneficial, it should not take the place of support from school administrators. Stakeholders in this effort include school- and district-level administrators and principal/administrator preparation programs. Both entities should consider how to prepare principals and administrators to co-design support for novice teachers and how to differentiate that support to meet the novice teachers’ unique needs, understand mentoring constellations, and understand the characteristics of effective mentoring.

6.2. Co-Designing Mentoring Support with Novice Teachers

School-level and district-level administrators will learn from their novice teachers when they listen to what they need. For example, Kathleen wished there had been a checklist “for the mentor [and] the admin[istrator] to better understand how to communicate with the new teacher”. While it would be unusual for a first-year teacher to be able to create such a checklist, it would be likely that a second- or third-year teacher could. In our interviews with Kathleen and other novice teachers, they were able to articulate which types of support mentors offered that were effective for them in their first years of teaching. This type of checklist could be developed cyclically. To keep the list up to date, a cycle of revisiting and revising the list with each group of early-career teachers would be necessary. This list could then be used to offer first-year teachers support. Teachers’ voices must be amplified so that school leaders may “consider the benefits of consulting with novice teachers about their expectations in the mentoring arrangement” [57].

6.3. Providing Differentiated Support

As Kathleen, Bailey, and Lindsay illustrate in their stories, there are some needs they all had in common, but there were also needs unique to each novice teacher. A checklist, as Kathleen suggested, would be one tool that school and district administrators could create to allow them to provide differentiated support to novice teachers. Lindsay also wished her support had been differentiated. In her third year, after moving to a different school district, she took part in a first-year program required for all new hires. However, she “did not find a lot of benefit” in the program, since it was geared toward teachers new to the profession. By thinking of novice teachers’ needs as we do those of our students, we will realize the need to differentiate the support we provide. In administrator preparation programs, principals and district-level administrators need to consider how they can pay attention to the support needed by different teachers. Given the time and resources to consider teachers’ needs, administrators will realize the need for effective and innovative resources for mentoring and induction. We recognize the need for resources co-designed by teachers, including novice teachers, mid- and late-career teachers (some who have served as mentors), teacher educators, educational leadership faculty, and elementary school administrators. Examples of resources include exemplary activities that can serve as provocations for mentor–novice teacher meetings, videos demonstrating effective mentoring practices, and resources for common novice teacher needs (planning, management, etc.) that could ultimately help retain and sustain them in the profession.

6.4. Mentoring Constellations

Mentors can play a vital role in a novice teacher’s success. When mentoring programs are even present, most school districts assign novice teachers only a single mentor who guides them through the induction period. However, there is considerable evidence [47,48,49,58] that novices in a wide range of careers benefit from a mentoring constellation rather than from a single mentor.

Among our participants, Kathleen is a good example of a novice teacher who took it upon herself to assemble a mentoring constellation. Kathleen began her teaching career a few months into the school year, so it took several months before she was assigned a single mentor by her school. Consequently, she used her prior relationships in the district to reach out to multiple educators to guide her and answer her many questions. Because Kathleen had access to a constellation of mentors, she relied on others to support her when her mentor was overwhelmed and could not provide support. It was not until her third year of teaching that she could rely on finding mentorship.

Bailey developed a constellation of mentors when she found her district-assigned mentor’s support trailed off after the beginning of her first year. These people included Bailey’s assistant principal and instructional coach. These mentors checked in on Bailey more frequently than her district-assigned mentor. She said that it “[made] more sense” to reach out to “other people who have more expertise and have been [teaching] longer”. She shared that she got to know her assistant principal and instructional coach well, and they “checked in” on her more than her mentor did.

Lindsay also had a constellation of mentors. In her first and second years of teaching, she received mentoring from a grade-level colleague, a district-assigned mentor, her principal, and two instructional coaches. During her third year, Lindsay moved to a new school district. In this district, Lindsay was not assigned a mentor, but she received support from her grade-level team, principal and assistant principal, and a social worker. Despite these constellations of mentors, Lindsay resigned from teaching during her third year. When asked why she left teaching, Lindsay listed “lack of support” as one reason. One factor that could have been integral in Lindsay’s decision to stay, despite having formed a constellation of mentorship, was the quality of the mentoring she received.

Constellations of mentors are important in a profession like teaching, in which many teachers and administrators are stretched thin. When novice teachers are surrounded by more than one mentor who can support them in different ways, the burden of supporting them is spread among several people. It also allows novice teachers to seek support or advice from colleagues based on their expertise, experience, and strengths. Novice teachers should be supported in building their constellation of mentors in a way that allows them to select people with whom they can have strong relationships and offer diverse support [58].

Johnson et al. [58] and Felten and Lambert [49] posit that people new to their professions should be taught to purposefully build their constellation of mentors. Bailey and Lindsay built their constellations of mentors, but not in purposeful ways. They advocated for themselves, though. When Lindsay moved to a different school district for her third year of teaching, she reached out to her colleagues to observe her teaching and provide feedback when she was struggling with students’ behaviors. By advocating for herself, Lindsay gathered several mentors to support her. Bailey advocated for herself after feeling that her district-assigned mentor had too much on her plate to be her only support. Bailey reached out to her assistant principal and instructional coach because she could be better supported by others. Kathleen, too, advocated for herself for mentoring support. She “took it upon herself” to seek support from her father’s colleague, who taught at a different school. Novice teachers could benefit from being taught in their teacher preparation and induction programs to build a constellation of mentors and advocate for themselves.

6.5. Effective Mentoring Practices

Effective support for novice teachers includes regular mentoring support with planning instruction, learning new pedagogical strategies, as well as meeting with other professionals to build collegial relationships in which novice teachers can develop as reflective practitioners [35,37,38,39]. Additionally, we propose that mentor training, release time for mentoring, and financial compensation for mentors are also critical for effective mentoring.

Whichever techniques an induction and mentoring program chooses to utilize, Kardos and Johnson [26] note that effective mentoring is a stabilizing mechanism that helps novice teachers gain their footing. In sum, novice teachers want to discuss their experiences and challenges with other educators. This process has been shown to aid novice teachers in advocating for their professional growth via feedback [39].

In this culture of heightened stress and pressure on teachers during a teacher shortage, we cannot simply pay lip service to this support by ensuring that mentoring is present and in a prescribed amount; rather, our time and energy should be focused on the quality of the mentoring if we are to retain and sustain novice teachers in the profession.

Author Contributions

Each author assisted equally in each of the elements associated with the construction of this article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Maris M. Proffitt and Mary Higgins Proffitt Endowment Grants, Indiana University, grant number 29-402-69 (PR-SD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Belmont Report and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ball State University (Approval Code: 1759537, Approval Date: 1 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to Institutional Review Board regulations and are part of an ongoing study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Margaret Ascolani. for her support in thoughtfully and compassionately conducting interviews with the participants throughout the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Protocols

Round 4

Welcome: During our conversation today, I am just going to ask you to reflect on the past year. First, congratulations for making it through your first year, especially during a pandemic.

Teaching Context: Let us start by reviewing to get some context. Could you restate what school you were working in?

And which district and grade level?

Looking back at this year, was instruction in person, virtual, hybrid, or a combination?

Reflecting Back: Thinking back to this past year, what lessons did you learn about your students?

What did you learn about yourself as a teacher this year?

Looking forward to next year and beyond, what teaching practices that were required during COVID do you hope go away?

Were there any teaching practices that required you adapting to COVID that you anticipate taking forward into the next year and beyond?

How do you think this experience will shape your future teaching?

Now turning to some of the highlights and struggles that you have this year:

What was the greatest success that you had?

On the flip side, what was your greatest challenge?

Support/Mentoring Network: Now we will shift and talk about the people who supported you professionally this year.

Looking back, who would you say supported you professionally?

How were you being supported by your mentor?

How did your support network evolve over the year?

Which relationships were the most beneficial for you this year?

Next Steps: After this interview, I will transcribe our conversation and attempt to illustrate your mentoring network. To make sure that I illustrate it correctly, and I capture your support system for this year, I would love to send you a copy of the illustration and then get your feedback and any edits that you see fit to make sure that I am representing that correctly. I will draft that up and send it to you soon.

Thank you so much for sharing your experience.

Round 7

WELCOME

Interviewer Statement: Thank you for continuing to participate in this research study. As you know, we are interested in understanding your experiences during the early years of your career.

CAREER REVIEW

Transition: Consistent with our last interview, the first set of questions aims to capture where you are working now and if there have been any changes in your position. We want to make sure we have an accurate understanding of your time as a teacher. Could you restate…

During your first year of teaching, what school did you teach in?

Could you restate the district that school was in?

Could you restate the grade that you taught during year 1?

Transition: Thank you for restating that information. Where are you teaching now? Which district is your school located in? What grade are you teaching this year?

How is it going so far this year? [Follow up as appropriate]

What challenges have you encountered this year?

What areas are you striving to grow in this year?

What areas do you feel most comfortable/confident in this year?

How would you describe where you are at this point in your career?

If they do not mention beginner, novice, new, mid-career, experienced, seasoned, master, veteran… something, follow up with:

Do you still think of yourself as a novice or beginner? Or something else?

INDUCTION AND MENTORING

Is there a statewide mentoring or induction program in [insert state/where you are teaching]?

If so, what does that look like?

Have you found that program to be helpful?

Describe your experience with your assigned mentor. Would you classify your assigned mentor as your primary mentor? If not, describe why.

Is there a district and/or building-level mentoring or induction program?

If so, what does that look like?

As part of this study, we are hoping to create some tools to help districts support new teachers.

Now that you are at this point in your career, what has been most helpful to you? Any particular support or tools that were useful?

What was missing that you think would be/would have been helpful to you?

Are you serving in any sort of mentoring role for newer teachers now, either formally or informally? If so, tell me about it.

INTERACTIVE ACTIVITY—Drawing your career

Transition: Thank you for outlining how induction/mentoring/support has/have looked in your career thus far. To better understand your experiences throughout the last 2.5 years, we would like to ask you to draw a line that represents your time as a teacher…

On this whiteboard (share Zoom whiteboard), draw a line that represents your experiences during your first 2.5 years of teaching considering highs, lows, and in-betweens. It might be straight, bumpy, or whatever makes sense given your experiences.

The interviewer models how to draw a line (thick pen works best).

[Let the participant play around with it, if needed. Have them clear the board and draw their line when they are ready. The interviewer waits while they draw. Once done, capture the drawing and label it with the participant’s pseudonym.]

“Now, describe the journey that is represented on the line”.

If you were to write an autobiography about your first few years as a teacher, what would the title be?

Why would you give your autobiography that title?

How might your journey you described with the line correlate to some chapters in this autobiography?

Is there anything else you would like to say, particularly in relation to your advice for assisting early-career teachers?

**Follow-up questions will be asked as appropriate.

CONCLUSION

Interviewer Statement:

Thank you so much for your time today. If you have any questions, do not hesitate to reach out to me via email.

References

- Wood, A.L.; Stanulis, R.N. Quality Teacher Induction: “Fourth-wave” (1997–2006) Induction Programs. New Educ. 2009, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, G.; Crowe, E.; Schaefer, B. The Cost of Teacher Turnover in Five School Districts: A Pilot Study; National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sutcher, L.; Darling-Hammond, L.; Carver-Thomas, D. A Coming Crisis in Teaching? Teacher Supply, Demand, and Shortages in the U.S. Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2016. Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/coming-crisis-teaching (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Britzman, D. Practice Makes Practice: A Critical Study of Learning to Teach, revised ed.; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Danielewicz, J. Teaching Selves: Identity, Pedagogy, and Teacher Education; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alsup, J. Teacher Identity Discourses: Negotiating Personal and Professional Spaces; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, M.L.; Phillips, D.K. Becoming a Teacher of Literacy: The Struggle Between Authoritative Discourses. Teach. Educ. 2005, 16, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiman-Nemser, S. From Preparation to Practice: Designing a Continuum to Strengthen and Sustain Teaching. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2001, 103, 1013–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellings, G.; Koopman, M.; Beijaard, D.; Mommers, J. Constructing Configurations to Capture the Complexity and Uniqueness of Beginning Teachers’ Professional Identity. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2023, 46, 372–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Fernandez, M.; Joo-Nagata, J.; Dobbs-Diaz, E.; Mardones-Nichi, T. Construction of Teacher Professional Identity through Initial Training. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.V.; Roller, C.; Maloch, B.; Sailors, M.; Duffy, G.; Beretvas, S.N. Teachers’ Preparation to Teach Reading and Their Experiences and Practices in the First Three Years of Teaching. Elem. Sch. J. 2005, 105, 245–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, R.; Helms-Lorenz, M.; Maulana, R.; Veen, K.V. The Longitudinal Effects of Induction on Beginning Teachers’ Stress. Br. Psychol. Soc. 2019, 89, 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressman, S.; Winter, J.S.; Efron, S.E. Next generation mentoring: Supporting teachers beyond induction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 73, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanks, R.; Attard Tonna, M.; Krøjgaard, F.; Annette Paaske, K.; Robson, D.; Bjerkholt, E. A Comparative Study of Mentoring for New Teachers. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2022, 48, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleas, E.K.; Code, M.A. Practice Teaching to Teaching Practice: An Autoethnography of Early Autonomy and Relatedness in New Teachers. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020933879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, N. The Liminality of New Foundation Phase Teachers: Transitioning from University into the Teaching Profession. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2017, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholam, A. A Mentoring Experience: From the Perspective of a Novice Teacher. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2018, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, S.; Davis, T.; Sydnor, J.; Ascolani, M. First-year Teachers Seek Mentoring and Stress Management During a Pandemic. In Research on Stress in Education: Implications for the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond; McCarthy, C.J., Lambert, R.G., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2023; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, E.D.; Woo, A. Job-Related Stress Threatens the Teacher Supply: Key Findings from the 2021 State of the U.S. Teacher Survey. RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-1.html (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Heubeck, E. Mentors Matter for New Teachers: Advice on What Works and Doesn’t. Education Week, 5 May 2021; 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Washington, V. A Case Study: A Novice Teacher’s Mentoring Experiences the First Year and Beyond. Educ. Urban Soc. 2022, 56, 309–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, L.A. Mentoring Novice Teachers. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2021, 29, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jotkoff, E. NEA Survey: Massive Staff Shortages in Schools Leading to Educator Burnout: Alarming Number of Educators Indicating They Plan to Leave Profession; National Education Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.nea.org/about-nea/media-center/press-releases/nea-survey-massive-staff-shortages-schools-leading-educator (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Simos, E. Why Do Teachers Leave? How Could They Stay? Engl. J. 2013, 102, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, L.U.; Koballa, T.R. Borders to cross: Identifying sources of tension in mentor-intern relationships. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 2132–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardos, S.M.; Johnson, S.M. On Their Own and Presumed Expert: New Teachers’ Experience with Their Colleagues. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2007, 109, 2083–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E.A.; Kain, J.F.; Rivkin, S.G. Why public schools lose teachers. J. Hum. Resour. 2004, 39, 326–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kini, T.; Podolsky, A. Does Teaching Experience Increase Teacher Effectiveness? A Review of the Research; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfeldt, M.; Loeb, S.; Wyckoff, J. How Teacher Turnover Harms Student Achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 50, 4–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]