Teacher and Middle Leader Research: Considerations and Possibilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

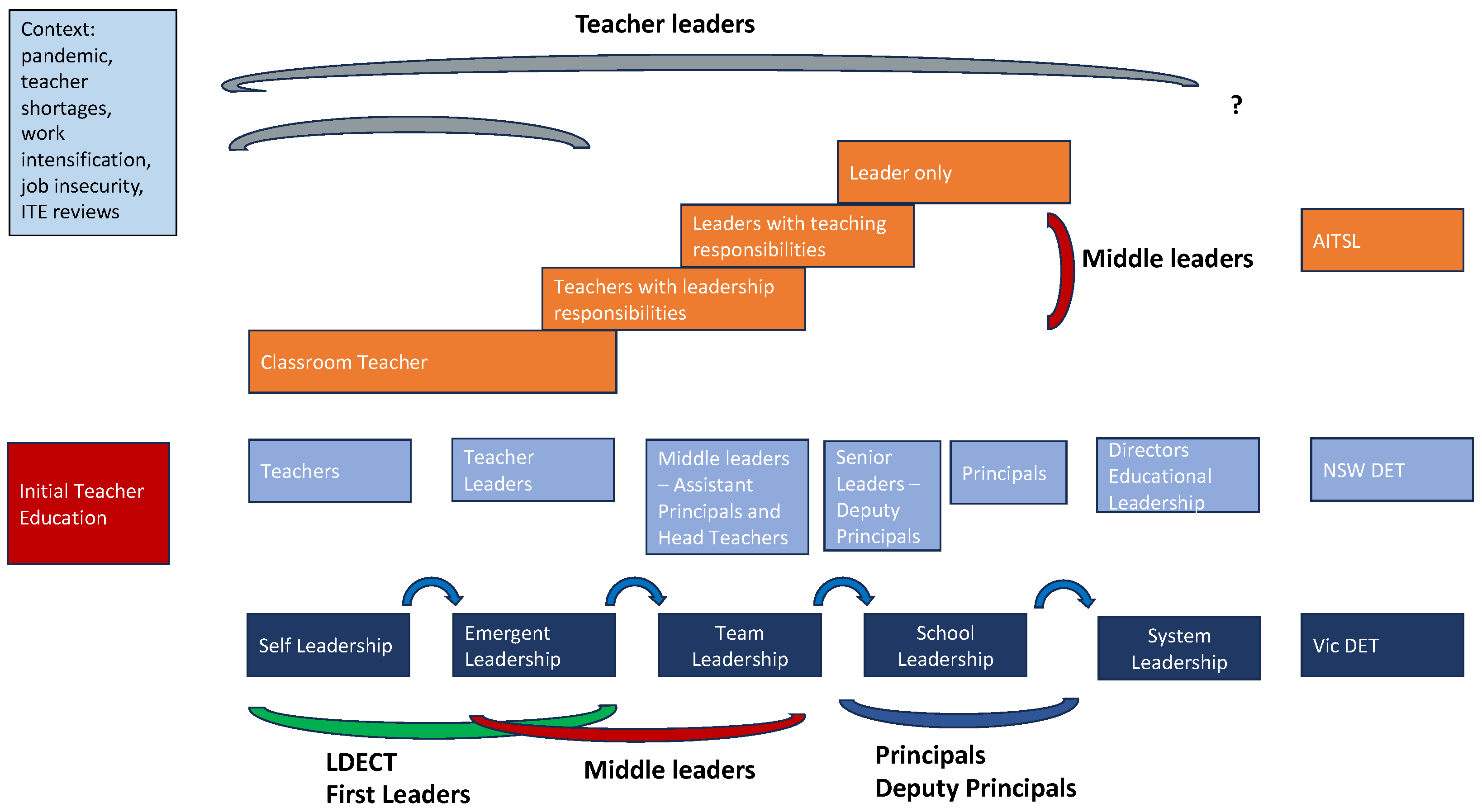

2. Defining Middle and Teacher Leadership

2.1. Definitions

2.1.1. Middle Leaders

2.1.2. Teacher Leaders

‘The process by which teachers, individually and collectively, influence their colleagues, principals and other members of the school communities to improve teaching and learning practices with the aim of increased student learning and achievement.’

‘…teachers who maintain K–12 classroom-based teaching responsibilities, while also taking on leadership responsibilities outside of the classroom.’

‘…lead within and beyond the classroom, identify with and contribute to a community of teacher learners and leaders, and influence others towards improved educational practice; and accept responsibility for achieving the outcomes of that leadership.’

2.2. A Statement about Context, Organisational Design and Teacher and Middle Leadership

2.3. Conclusions

3. Volume and Sources of Research Information

4. Trustworthy Claims about the Work of Middle and Teacher Leaders

- Claim 1: Teacher and middle leadership are not the same concepts, although there might be overlap depending on how they are defined. Teacher leadership is mostly about the work of teachers who exert influence on teachers and the school beyond their teaching work, and these people do not have a formal leadership or organizational role outside of their teaching. Middle leadership is mostly about teachers who also have a formal leadership or organizational role, and exert influence on teachers and the school.

4.1. Impact

- Claim 2: Teacher and middle leaders can impact significantly on students, teachers and schools.

4.2. Interventions

- Claim 3: The way middle and teacher leadership is enacted varies across contexts, but there are consistent elements that include improving teaching and learning, working collegially with colleagues and fostering collective endeavour, improving school conditions and being critically reflective about what schools do.

- Inputs. Middle leadership is enhanced when the following aspects are present: principal support, school/system culture, professional development, enthusiasm/drive, and knowledge of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment.

- Roles. Middle leaders can have multiple roles that can be student-focused, administrative, organisational, supervisory, staff development and strategic. These are ordered from managerial (student-focused) to leadership (strategic).

- Enactment of roles. The roles are enacted through managing relationships, leading teams, communicating effectively, managing time and managing self.

- Outputs. The work of middle leaders can impact teacher quality, teacher attitudes and student outcomes.

- Leading—teaching: teaching and leading practices are viewed as intertwined and working together. Leadership practices are enhanced through their teaching experience but constrained by having to be in the classroom. Modelling is a core practice.

- Managing—facilitating: This is focused on ‘administrative and pragmatic practices related to professional and curriculum development’ (p. 84). Bridging and brokering are core practices.

- Collaborating—communicating: The key idea is that leadership is realized through the practices of others and the focus is on creating communicative spaces for teachers to collegially develop and share pedagogical practices. Communication is a core practice.

‘The practice of middle leading involves engaging in (simultaneous) leading-teaching by managing and facilitating educational development through collaborating and communicating to create communicative spaces open and responsive to the change needed for developing particular practices of teaching and learning in this school or that.’ ([44], p. 248)

- continuing to teach and improve their own individual teaching proficiency and skill

- organising and leading peer review of teaching practices

- providing curriculum development knowledge

- participating in school-level decision making

- leading in-service training and staff development activities

- engaging other teachers in collaborative action planning, reflection and research

- Coordination and management

- School or district curriculum work

- Professional development of colleagues

- Participation in school change/reform/improvement

- Parent and community involvement

- Pre-service teacher education

- Action research

- Promoting social justice

- Domain I: Fostering a collaborative culture to support educator development and student learning

- Domain II: Accessing and using research to improve practice and student learning

- Domain III: Promoting professional learning for continuous improvement

- Domain IV: Facilitating improvements in instruction and student learning

- Domain V: Promoting the use of assessments and data for school and district improvement

- Domain VI: Improving outreach and collaboration with families and community

- Domain VII: Advocating for student learning and the profession

4.3. Leadership Focus

- Claim 4: Middle and teacher leaders can have a leadership focus when there are high expectations and role clarity in regard to this work.

4.4. Identification

- Claim 5: Leadership preparation needs to begin in initial teacher training, and then leadership skills, qualities and dispositions need to be developed and supported through teacher, middle and senior leadership phases.

4.5. Supports and Hindrances

- Claim 6: Teacher and middle leadership work can be supported through developing leadership expectations in teachers, providing leadership preparation and development programs, ensuring work roles are well defined, having both leadership and management expectations, having a supportive school culture and structure, and having the support of the principal and other senior leaders. The absence of these diminishes the work of teachers and middle leaders.

5. Conclusions—Policy Implications, Practice Recommendations and Future Research Directions

5.1. Introduction

5.2. Policy Implications and Practice Recommendations

5.3. Reflection on Future Research

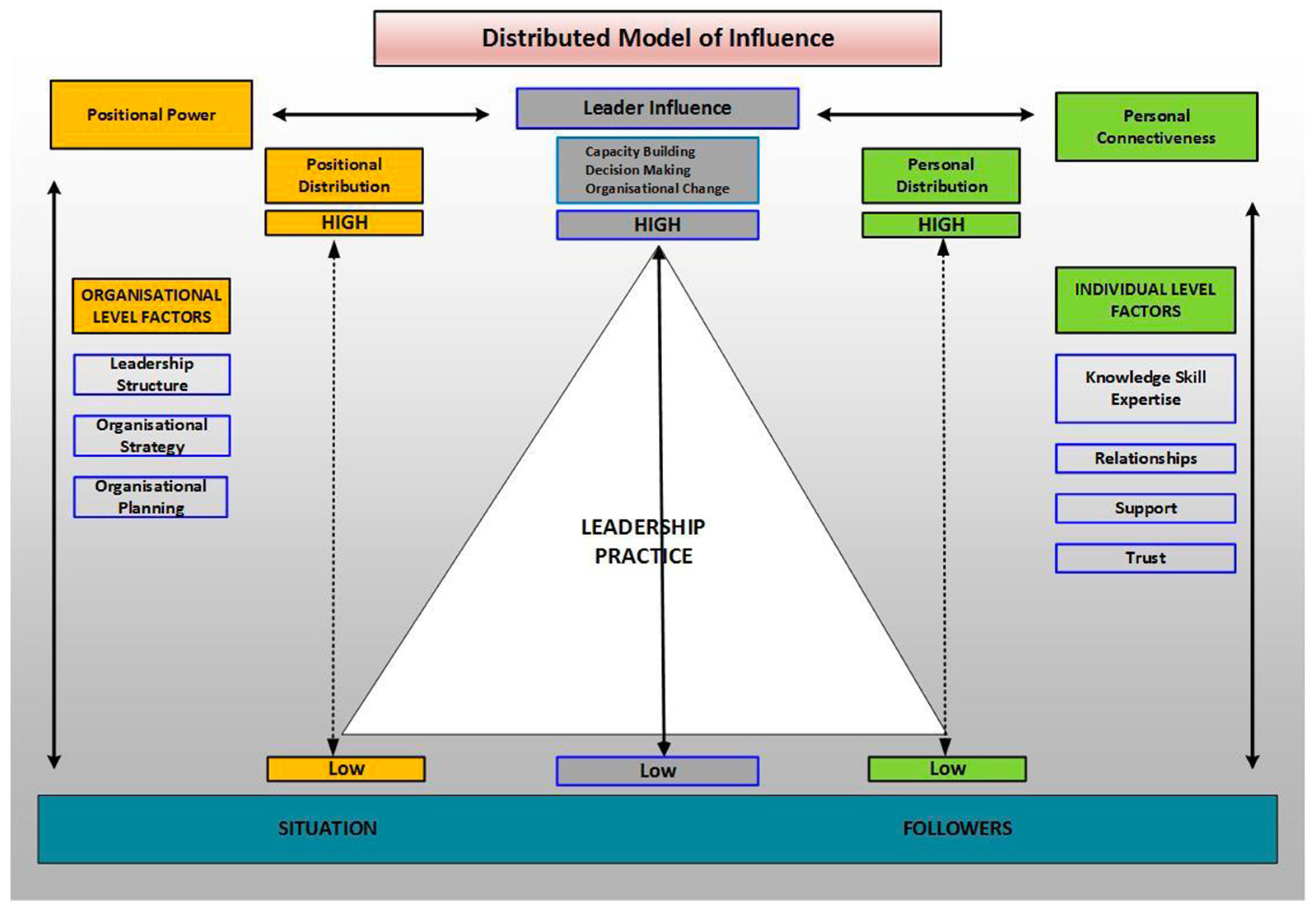

‘At the centre of the model is a triangle which represents the leader/follower/situation triad…Situation and followers are located at the bottom vertices in the blue bar, and the leader (or leader influences) is located at the top vertex. Running vertically through the middle of the triangle is a line which represents the level of influence. Leader influence is indicated in grey at the top of the line and is concerned with leadership practices associated with capacity building, decision making and organisational change. High levels of influence will utilise all three practice areas more often.

There are two components to the model which impact leader influence, and these are Positional Power (yellow) and Personal Connectiveness (green)…

5.4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bush, T. Preparation and induction for school principals: Global perspectives. Manag. Educ. 2018, 32, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelle, P.S.; DeHart, C.A. Comparison and Evaluation of Four Models of Teacher Leadership. Res. Educ. Adm. Leadersh. 2016, 1, 85–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J. Connecting Teacher Leadership and School Improvement; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.; Harris, A.; Ng, D. A review of the empirical research on teacher leadership (2003–2017): Evidence, patterns and implications. J. Educ. Adm. 2020, 58, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, C.; van Roekel, H.; Tummers, L.G. Teacher leadership: A systematic review, methodological quality assessment and conceptual framework. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 31, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenner, J.A.; Campbell, T. The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 87, 134–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York-Barr, J.; Duke, K. What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from two decades of scholarship. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 255–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J. Towards a theoretical model of middle leadership in schools. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2018, 38, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J. Researching middle leadership in schools: The state of the art. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2021, 49, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Grootenboer, P.C. The Practices of School Middle Leadership. Leading Professional Learning; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D. A review of Research on Middle Leaders in Schools. In International Encyclopedia of Education; Tierney, R., Rizvi, F., Ercikan, K., Smith, G., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L. Middle-level school leaders: Potential, constraints and implications for leadership preparation. J. Educ. Adm. 2013, 51, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M.; Ismail, N.; Nguyen, D. Middle leaders and middle leadership in schools: Exploring the knowledge base (2003–2017). Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2019, 39, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscombe, K.; Tindall-Ford, S.; Lamanna, J. School middle leadership: A systematic review. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2023, 51, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Bringing context out of the shadow. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, C.F. The need for cross-cultural exploration of teacher leadership. Res. Educ. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 6, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, C.F. (Ed.) Teacher Leadership in International Contexts; Springer: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, C.F.; Okoko, J.M. Exploring teacher leadership across cultures: Introduction to teacher leadership themed special issue. Res. Educ. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.; Miller, J. (Eds.) Bush Tracks. The Opportunities and Challenges of Rural Teaching and Leadership; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, L.; Miller, J.; Paterson, D. Early career opportunities in Australian rural schools. Educ. Rural. Aust. 2009, 19, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.B.; Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L. School Leadership and Management in Sindh Pakistan: Examining Headteachers Evolving Roles, Contemporary Challenges, and Adaptive Strategies. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranston, N.C. Middle-level school leaders: Understanding their roles and aspirations. In Australian School Leadership Today; Cranston, N.C., Ehrich, L.C., Eds.; Australian Academic Press: Samford Valley, QLD, Australia, 2009; pp. 217–241. [Google Scholar]

- De Nobile, J.; Ridden, P. Middle leaders in schools: Who are they and what do they do? Aust. Educ. Lead. 2014, 36, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Flessa, J.J. Principals as middle managers: School leadership during the implementation of primary class size reduction policy in Ontario. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2012, 11, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. Leadership from the middle. Educ. Can. 2015, 55, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A.; Ainscow, M. The top and bottom of leadership and change. Phi Delta Kappan 2015, 97, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Grice, C. Investigating the Influence and Impact of Leading from the Middle: A School-Based Strategy for Middle Leaders in Schools. Executive Summary; Report Commission by the Association of Independent Schools Leadership Centre; University of Sydney: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards-Groves, C.; Grootenboer, P.; Hardy, I.; Rönnerman, K. Driving change from ‘the middle’: Middle leading for site based educational development. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2019, 39, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.B. School principals acting as middle leaders implementing new teacher evaluation systems. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.-L.W.; Wiens, P.D.; Moyal, A. A bibliometric analysis of the teacher leadership scholarship. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 121, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenmeyer, M.; Moller, G. Awakening the Sleeping Giant: Helping Teachers Develop as Leaders; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.; Cambron-McCabe, N.; Lucas, T.; Smith, B.; Dutton, J.; Kleiner, A. Schools That Learn: A Fifth Discipline Fieldbook for Educators, Parents, and Everyone who Cares about Education; Nichlas Brealey Publishing: London, UK, 2000; pp. 27–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lipscombe, K.; De Nobile, J.; Tindall-Ford, S.; Grice, C. Formal Middle Leadership in NSW Public Schools: Full Report; Department of Education: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2020.

- Victorian Academy of Teaching and Leadership. Talent Management Framework. 2023. Available online: https://www.academy.vic.gov.au/initiatives/talent-management-framework (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). Australian Teacher Workforce Data National Trends; Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Gurr, A.; Gurr, Z.; Jarni, B.; Major, E. Leadership demands on four early career teachers. In Understanding Teacher Leadership in Education Change: An International Perspective; Liu, P., Thien, L.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- De Nobile, J. Neither Senior, nor Middle, but Leading Just the Same: The Case for First Level Leadership. Leadersh. Manag. 2023, 29, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, R. How Leadership Is Manifested in Steiner Schools. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, V. Future School. How Schools around the World Are Applying Learning Design Principles for a New Era; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Speak a Different Language: Reimagine the Grammar of Schooling. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2020, 48, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. Middle leaders matter: Reflections, recognition, and renaissance. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2017, 37, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Bryant, D.; Walker, A. School middle leaders as instructional leaders: Building the knowledge base of instruction oriented middle leadership. J. Educ. Adm. 2022, 60, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, F.; Ferguson, M.; Hann, L. Developing Teacher Leaders, 2nd ed.; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grootenboer, P.; Rönnerman, K.; Edwards-Groves, C. Leading from the middle: A praxis-orientated practice. In Practice Theory Perspectives on Pedagogy and Education: Praxism Diversity and Contestation; Grootenboer, P., Edwards-Groves, C., Choy, S., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2017; pp. 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D. School middle leaders in Australia, Chile and Singapore. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2019, 39, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A. Empowering middle leaders—Trends in school leadership research on the principal’s impact on school effectiveness. Aust. Educ. Lead. 2016, 38, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dinham, S. Principal Leadership for Outstanding Educational Outcomes. J. Educ. Adm. 2005, 43, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinham, S. The secondary head of department and the achievement of exceptional student outcomes. J. Educ. Adm. 2007, 45, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highfield, C. The Impact of Middle Leadership Practices on Student Academic Outcomes in New Zealand Secondary Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. Department-head leadership for school improvement. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2016, 15, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, M. The role of middle leaders in New Zealand secondary schools: Expectations and challenges. Waikato J. Educ. 2016, 21, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farchi, T.; Tubin, D. Middle leaders in successful and less successful schools. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2019, 39, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.; Conway, J.; Dawson, M.; Lewis, M.; McMaster, J.; Morgan, A.; Star, H. School Revitalisation: The IDEAS Way; Australian Council for Educational Leaders: Surry Hills, NSW, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, F.M. From School Improvement to Sustained Capacity: The Parallel Leadership Pathway; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, F.M.; Boyne, K. Energising Teaching: The Power of Your Unique Pedagogical Gift; ACER: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, H.H. The Leadership Role of Middle Leaders in Six Selected Primary Schools in Singapore. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos, M. Educational Leadership and the Contribution of the Technical Pedagogical Head across Three Types of Schools in One Chilean Region. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, D.A.; Wong, Y.L.; Adames, A. How middle leaders support in-service teachers’ on-site professional. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 100, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J.; Lipscombe, K.; Tindall-Ford, S.; Grice, C. Investigating the roles of middle leaders in New South Wales public schools: Factor analyses of the Middle Leadership Roles Questionnaire. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootenboer, P.; Edwards-Groves, C. The Theory of Practice Architectures. Researching Practice; Springer: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tindall-Ford, S.; Grootenboer, P.; Edwards-Groves, C.; Attard, C. Understanding School Middle-Leading Practices: Developing a Middle-Leading Practice Model. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). Professional Standards for Middle Leaders; Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Muijs, D.; Harris, A. Teacher Led School Improvement: Teacher Leadership in the UK. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2006, 22, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teacher Leadership Exploratory Consortium. Teacher Leader Model Standards; Teacher Leadership Exploratory Consortium: Reston, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Doraiswamy, N.; Wilson, G.; Czerniak, C.M.; Tuttle, N.; Porter, K.; Czajkowski, K. Teacher leader model standards in context: Analyzing a program of teacher leadership development to contextual behaviours of teacher leaders. Eur. J. Educ. Manag. 2022, 5, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supovitz, J.A. Teacher leaders’ work with peers in a Quasi-formal teacher leadership model. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2018, 38, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. J. Educ. Adm. 2011, 49, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, C.F.; Pineda-Báez, C.; Gratacós, G.; Wachira, N.; Nickel, J. Who is interested in teacher leadership and why? In Teacher Leadership in International Contexts; Webber, C.F., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2023; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, L.; Gurr, D.; Goode, H. Dare to make a difference: Successful principals who explore the potential of their role. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2016, 44, 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cotter, M. Examination of the Leadership Expectations of Curriculum Coordinators in the Archdiocese of Melbourne—A Case Study Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, W. Case Studies in Learning Area Leadership in Catholic Secondary Schools in Melbourne. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- White, P. The Leadership of Curriculum Area Middle Managers in Selected Victorian Government Secondary Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, D.; Walker, A. Principal-designed structures that enhance middle leaders’ professional learning. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2024, 52, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.; Brundrett, M. Growing the leadership talent pool: Perceptions of heads, middle leaders and classroom teachers about professional development and leadership succession planning within their own schools. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2009, 35, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaro, D.; Gurr, D. Leadership Development in Initial Teacher Education. In Encyclopedia of Teacher Education; Peters, M., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2022; 5p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaro, D.; Gurr, D. Challenging Leadership Norms—Fostering Leadership in Initial Teacher Education. In The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Leadership and Management Discourse; English, F.W., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2022; 16p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, M.; Robson, J. The two towers: The quest for appraisal and leadership development of middle leaders online. J. Open Flex. Distance Learn. 2017, 21, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.; Chan, T.K. Continuing professional development for middle leaders in primary schools in Hong Kong. J. Educ. Adm. 2014, 52, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poekert, P.; Alexandrou, A.; Shannon, D. How teachers become leaders: An internationally validated theoretical model of teacher leadership development. Res. Post-Compuls. Educ. 2016, 21, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, A.; Bennett-Powell, G. The perceptions of secondary school middle leaders regarding their needs following a middle leadership development programme. Manag. Educ. 2014, 28, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, C.F. Lessons Learned from Voices Across the Globe. In Teacher Leadership in International Contexts; Webber, C.F., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2023; pp. 323–344. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Nicholas, D. Teacher and middle leadership: Resolving conceptual confusion to advance the knowledge base of teacher leadership. Asia Pac. J. Educ. Educ. 2023, 38, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A.; O’Connor, M.T. Collaborative Professionalism: When Teaching Together Means Learning for All; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J.; Zuberi, A. Designing and piloting a leadership daily practice log: Using logs to study the practice of leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2009, 45, 375–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootenboer, P.; Edwards-Groves, C.; Rönnerman, K. Leading practice development: Voices from the middle. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2015, 41, 508–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hord, S.M.; Sommers, W. Leading Professional Learning Communities: Voices from Research and Practice; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, D. Distributed Leadership in Successful Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, the University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Australian Professional Standards for Teachers | Professional Standards for Middle Leaders Australian | Australian Professional Standard for Principals |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Know students and how they learn 2. Know the content and how to teach it 3. Plan for and implement effective teaching and learning 4. Create and maintain supportive and safe learning environments 5. Assess, provide feedback and report on student learning 7. Engage professionally with colleagues, parents/carers and the community | STANDARD 1 Enabling dispositions 1a. Open-mindedness 1b. Interpersonal courage 1c. Empathy 1d. Perseverance and resilience STANDARD 2 Enabling knowledge and skills 2a. Using relevant knowledge 2b. Solving complex problems 2c. Building relational trust 2d. Self-reflection STANDARD 3 Enhancing understanding and respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 3a. Histories 3b. Communities 3c. Reconciliation 3d. Monitoring learning progress STANDARD 4 Coordinating high impact teaching and learning 4a. Curriculum 4b. Pedagogy 4c. Assessment STANDARD 5 Leading improvement in teaching practice 5a. Professional learning 5b. Evidence-informed practice 5c. Collaborative practice STANDARD 6 Managing effectively 6a. Ensuring a safe, supportive and orderly learning environment 6b. Students, parents/carers and the community 6c. Staff management 6d. Resource allocation 6e. Strategic planning 6f. Administrative systems and processes | Personal qualities, social and interpersonal skills Vision and values Knowledge and understanding Leading teaching and learning Developing self and others Leading improvement, innovation and change Leading the management of the school Engaging and working with the community |

| Area and Claim | Policy Implications | Practice Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher and Middle Leader Definitions. Claim 1: Teacher and middle leadership are not the same concepts, although their might be overlap depending on how they are defined. Teacher leadership is mostly about the work of teachers who exert influence on teachers and the school beyond their teaching work, and these people do not have a formal leadership or organizational role outside of their teaching. Middle leadership is mostly about teachers who also have a formal leadership or organizational role, and exert influence on teachers and the school. | Understanding and clearly describing the career stages and work of teachers and school leaders is important and needs to be incorporated by education systems into how they think about their teacher workforces. | Both teacher leadership and middle leadership conceptions be used to frame how the work of teachers and school leaders in an educational jurisdiction is described. Teacher leadership should be associated with teachers without formal organisational roles, and middle leadership with teachers with an additional formal organisational role. |

| Impact Claim 2: Teacher and middle leaders can impact significantly on students, teachers and schools. | In many jurisdictions, teacher and middle leaders will be key players in school and system success, and systems should be actively developing and supporting these roles in schools where possible and appropriate. | Systems and school leaders need to actively support the development of teacher and middle leaders so that their work impacts students, teachers and schools. |

| Interventions Claim 3: The way middle and teacher leadership is enacted varies across contexts, but there are consistent elements that include improving teaching and learning, working collegially with colleagues and fostering collective endeavour, improving school conditions and being critically reflective about what schools do. | Teacher and middle leadership needs to be part of how systems conceive of schools and the career progression of teachers. | Systems need to develop models/conceptions/standards that help describe outstanding middle and teacher leadership work. |

| Leadership focus Claim 4: Middle and teacher leaders can have a leadership focus when there are high expectations and role clarity in regard to this work. | Systems need to incorporate a leadership focus into how teacher and middle leadership is conceived. | Systems need to develop models/conceptions/standards that clearly describe the leadership work of middle and teacher leaders. |

| Identification Claim 5: Leadership preparation needs to begin in initial teacher training, and then leadership skills, qualities and dispositions need to be developed and supported through teacher, middle and senior leadership phases. | Systems need to have leader identification and support strategies and services in place for all career stages. | Systems need to develop leadership identification and support programs and processes that address all stages of teacher and school leader career progression. |

| Supports and hindrances Claim 6: Teacher and middle leadership work can be supported through developing leadership expectations in teachers, providing leadership preparation and development programs, ensuring work roles are well defined, having both leadership and management expectations, having a supportive school culture and structure, and having the support of the principal and other senior leaders. The absence of these diminishes the work of teachers and middle leaders. | Systems can be more proactive in how they support the work of middle and teacher leaders, including role clarification, provision of professional learning, engaging principals and other school leader support, and fostering school cultures and structures that support and value the work of middle and teacher leaders. | School leaders need to clearly define the work of middle leaders and include explicit leadership expectations and provide active support professional support that includes professional learning and supportive school structures. Middle leaders need to be proactive in their own professional development. School leaders need to recognise and nurture teacher leadership and provide appropriate professional learning support. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gurr, D. Teacher and Middle Leader Research: Considerations and Possibilities. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080875

Gurr D. Teacher and Middle Leader Research: Considerations and Possibilities. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(8):875. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080875

Chicago/Turabian StyleGurr, David. 2024. "Teacher and Middle Leader Research: Considerations and Possibilities" Education Sciences 14, no. 8: 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080875

APA StyleGurr, D. (2024). Teacher and Middle Leader Research: Considerations and Possibilities. Education Sciences, 14(8), 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080875