Promoting Sustainability Together with Parents in Early Childhood Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the main drivers inspiring families involved in our kindergarten recycling project to take action in protecting the environment and contributing to a more sustainable future?

- How did the kindergarten environmental project succeed in raising children’s environmental awareness and enhancing dialogue between parents and kindergarten professionals?

- How can the drivers and successful practices identified in the project be integrated into kindergarten educational practices to enhance sustainable development education?

2. Environmental Education for Sustainable Development

3. The Crucial Role of Early Childhood Sustainable Education

4. Environmental Sensitivity

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Context of the Study

5.2. Case Study

5.3. Multimethods

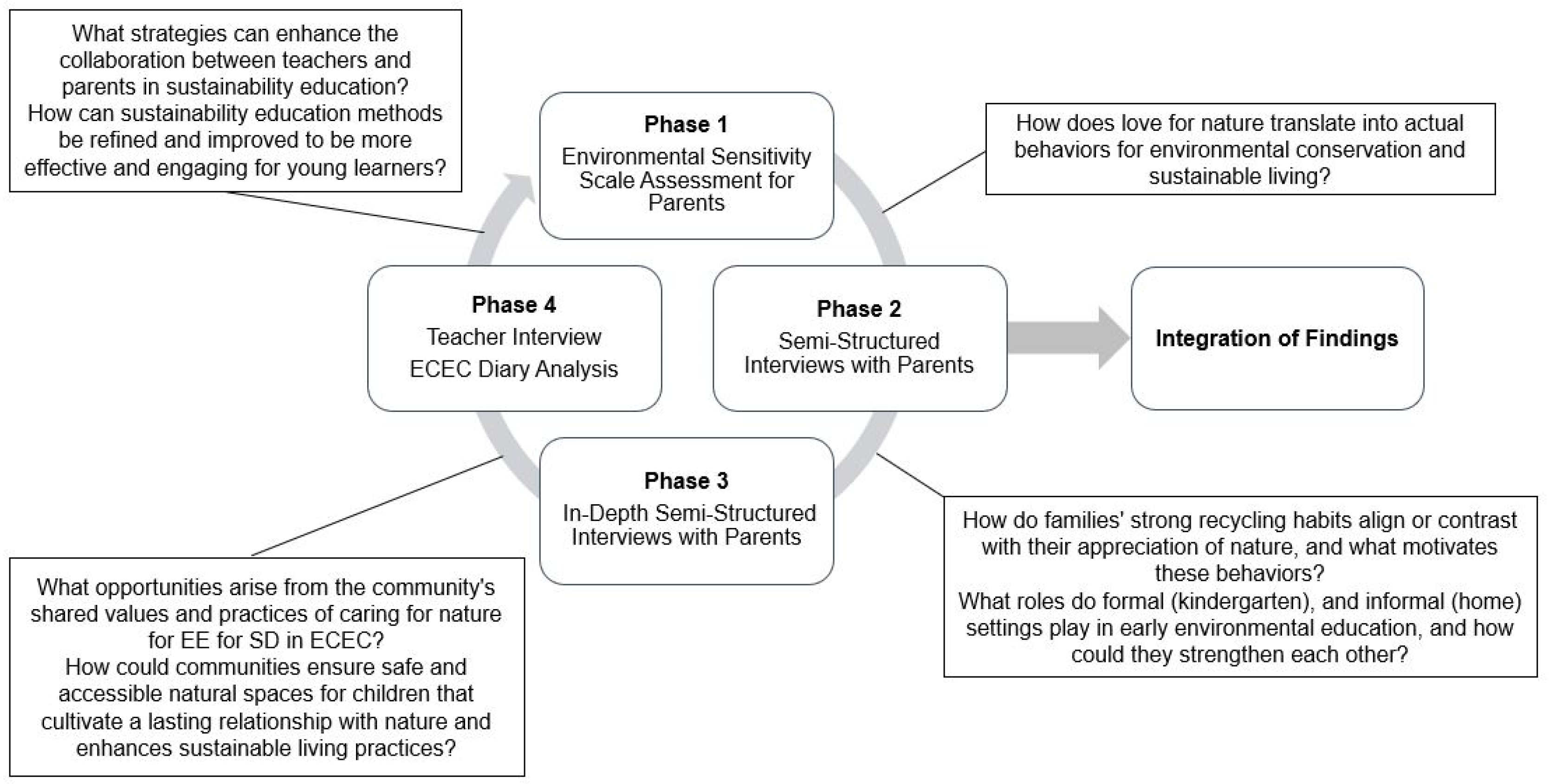

5.3.1. Phase 1: Environmental Sensitivity Scale

5.3.2. Phase 2: Parent Interviews

5.3.3. Phase 3: In-Depth Interviews with Parents

5.3.4. Phase 4: Kindergarten Professionals’ Perspectives

6. Results

6.1. Phase 1: Environmental Sensitivity Scale

6.2. Phase 2: Parent Interviews

6.2.1. Valuing and Promoting a Sustainable Lifestyle among Parents

6.2.2. The Importance of Nature and Outdoor Activities for Families

6.2.3. Parental Insights on the Project and Its Influence

6.3. Phase 3: In-Depth Interviews with Parents

6.3.1. Viewing Care for Nature as a Shared Community Value

6.3.2. The Depth of Parents’ Relationship with Nature and Their Environmental Expertise

6.3.3. Emphasizing the Importance of Children’s Connection with Nature and Fostering a Sustainable Lifestyle

6.4. Phase 4: Kindergarten Professionals’ Perspectives

- The children’s learning was notably enhanced through hands-on activities. The decomposition experiment was particularly engaging and exciting and prompted reflection at home. However, the concept of decomposition was found to be too abstract for some children;

- The recycling song effectively reinforced the concepts learned in the recycling activities;

- The children displayed significant enthusiasm in collecting trash, a practice that extended beyond the kindergarten environment;

- To avoid causing climate anxiety, the video about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch was not shown;

- The children quickly absorbed the learning material, especially with repetitive activities like sorting, which soon became self-evident;

- The importance of the collective commitment of all who work in the kindergarten to the methods and adherence to agreed practices was emphasized;

- The lack of children’s literature on the topic was noted;

- Crafts made from recycled materials were particularly enjoyed by the children;

- Challenges were identified in making the project sufficiently visible to parents and involving them more effectively.

- Activities should be better tailored to different age levels, utilizing differentiation and organizing children into small groups;

- It is important to familiarize children with concepts, like using a composter, before conducting experiments on abstract concepts like decomposition;

- There is a need to plan for better engagement of parents in the project.

6.5. Integration of the Results

- Strong Nature Connection: An intrinsic appreciation for and connection to the natural environment motivates families to undertake actions that protect and preserve it.

- Family Values and Practices: The transmission of sustainable values and practices within families encourages members to live in ways that are mindful of environmental impact.

- Socio-Cultural Context: Cultural identity and societal norms influence families’ perceptions of sustainability, embedding environmental responsibility into their daily lives.

- Strengthening nature connections through outdoor and nature-based learning activities, such as forest explorations, outdoor classroom sessions, and allowing children to play and explore nature freely.

- Promoting parent–kindergarten collaboration by:Enhancing dialogue between parents and kindergarten professionals through regular communication channels, such as newsletters, dedicated meetings, and digital platforms. These channels can share insights into the kindergarten’s environmental activities and gather feedback from parents.Exploring flexible engagement opportunities to accommodate time constraints.Leveraging parents’ expertise in sustainability to benefit EE planning and practices.Organizing family sustainability events, including workshops for parents and children on environmental practices and projects that families can continue at home.

- Involving the wider community in sustainability events, such as joint garbage collection events, flea markets, goods exchange markets, and sustainability workshops. Planning and implementing these events in collaboration with the community, including parents’ teams, local expertise associations, scouts, etc., are essential, considering time constraints.

- Expanding educational resources by equipping kindergartens with diverse resources, including books, games, and digital media focused on sustainability topics. Additionally, providing ongoing professional development opportunities for educators in environmental education can ensure teaching strategies remain innovative and effective.

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Project mapAims: To involve parents and other staff in the project.Short description: The project map is a pedagogical documentation. It is on the kindergarten wall for all to see. The map includes, for instance, wake up information such as photos and drawings, information of the actions and questions for the parents and staff. The information increases with the project. Parents are also able to ask questions and share their ideas with the teachers especially when picking up their children from kindergarten.

- Emotion photos of everyday living environmentAims: To awaken parents’ and children’s curiosity and interest in what kinds of thoughts or emotions the observations in their own living environment stimulate and elicit. Possibly, observations also lead to changes in manners of behavior.Short description: Parents and children are asked to observe their living environment and take photos of the views that stimulate and elicit positive or negative feelings.Example A1. Picture of dog poopObservations awaken emotions and possibly affect behavior.The child observes dog poop. “This is not nice because I might step on it”.Example A2. Picture of New Year’s trashRealizing one’s own behavior affects one’s emotions and possibly behavior. Children walk around the neighborhood after the New Year’s celebration. They observe plenty of trash from fireworks. The child says, “My family fired fireworks. These little pieces of fireworks look bad. It is so difficult to pick them up. We cannot shoot them here anymore”.

- These things do not belong to my play environmentAims: To understand how a phenomenon called littering appears in a child’s own play environment. To form an understanding of the concept “litter” at the qualitative level. To learn the first steps of classification (or categorization): belong to nature/does not belong to nature. To give children a possibility to reflect on the experience and discuss and express the feelings the littering evokes.Short description: Children make observations in their own play and learning environments near a kindergarten center. They are asked if they notice anything that does not belong to the environment. Children and adults pick up trash. Afterwards, in the reflection session, children are free to ask questions and discuss their experience. Emotion cards are used in discussions to assist conversation. Teachers can ask leading questions such as is there something which does not belong to our play environment and where does the trash come from?

- Trash BingoAims: To develop classification skills. To learn to sort waste.Short description: Children receive an open task where they are asked to sort the waste, which they picked up from the forest, in their own way. Their ideas of classifications are discussed, or the teacher can help with some leading questions. Next, kids play Trash Bingo. Trash Bingo is a game where different categories are described with pictures according to the common recycling system. The children are asked to set pictures of waste on the bingo plate. They are asked to take Trash Bingo home and to teach their parents to play it. Furthermore, the children and adults recycle all the trash by taking it to the appropriate recycling bins in the day care center.In classification learning sessions, teachers can assist children, for instance, by asking questions such as: Are the objects alike or different? How are they different? (color, size, shape, texture…). What does the trash in the same category have in common?To lead the children to the next action, teachers ask: What do you think that would have happened to the trash if you had not collected it?

- Production from wasteAims: To promote logical thinking skills by thinking about which trash can be reused in different products. To enlarge classifications with new categories. To wake up understanding why recycling trash benefits societies.Short description: Large pictures of products, which are made from recycled waste, are placed on the walls: cars, carton, plant soil bags, warm home, clothes, watering can, flea markets and thrift stores, glass bottles, etc. Children are given picture cards of different types of waste. One child at a time picks up a trash card. He or she is asked to think about what products could be made from that waste. The solution is reached together. The card is placed in the correct position on the wall by the movement indicated by the exercise dice.Teachers can assist children’s thinking by asking what similarities and differences between the products and waste there are.

- Waste reduction and reuseAims: To discover that everyone has an opportunity to affect the amount of waste by their own choices.Short description: In a weekly child meeting, they are asked to think if they have any toy at home that they do not need any more. Children and teachers share their ideas of how somebody else can benefit from the toy or other product that is unnecessary for themselves. It is also discussed if the product can be reused in another way, in another context, or if it can be shaped for another use. The recycle box for evaluation forms for later use is built together from the used products. In addition, children set up a flea market for toys at the day care center.Teachers can promote discussions by asking leading questions such as: Do you have any toys that you have not played with in a long time? What could we do with useless toys? If we do not make choices with the toys, where do they end up?

- Decomposition experiments in the day care gardenAims: To learn to make hypotheses, observations, and experiments. To observe that trash decomposition rates vary depending on type. To develop a sense of time by linking the findings of the experiments and hypothesis to familiar events. To promote understanding of decomposition and its importance in the ecosystem.Short description: Waste, such as aluminum cans, ice cream wrappers, banana peels, cigarette butts, plastic bags, wool socks, etc., are placed underground in the day care garden. Children create hypotheses of how long they expect waste to decompose under the ground. Children are encouraged to discuss the arguments they have for their assumptions. The estimations are made by linking the time scale to the familiar events in their life. The time scale is presented visually. Children ask their parents to estimate how much time it takes the buried products to decompose. The evaluation forms are visual. They are dropped into the recycle estimation box. The products are placed underground in the fall and in the spring the observations of their condition are made. The analysis and comparison with the hypothesis are made. A short movie on decomposition and its importance in the ecosystem is watched and discussed. The time scale of decomposition of different materials is perceived together with Lego bar charts. An exhibition of the decomposition and its rate is built in the day care hall. Children also visit a home where owners show how they sort, recycle, and decompose waste.The importance of decomposition is learnt with the Earthworm Soil Factory. Children feed worms with their leftovers. Children observe that earthworms break food into tiny pieces and those pieces become part of the soil (decomposition). Therefore, those animals can be called decomposers. Children plant seeds to recognize that in addition to worms, plants also need “food” (nutrients) to live and grow.

- Recycling trainAims: To empower children. To awaken positive emotions of successful learning and actions towards a cleaner environment. To learn self-assessment.Short description: Children are given, two at a time, responsibility for sorting and recycling the waste produced in kindergarten during their day. The trash is sorted into the recycling train and the trash is taken out to the waste containers with the train.

- The washing of trash, packaging, and waste into creeks, rivers, lakes and from there to the ocean.Aims: To understand that trash, thrown onto the ground, may enter the water systems with rainwater, causing problems for animals, plants, and humans.Short description: Children are given photos of creeks, rivers, lakes, and oceans. These concepts are discussed, and a short movie of the oceans is watched. A scale model of the creeks, rivers, lakes, and oceans is made from recycled materials. The model is filled with water and children can drop trash and observe, with the running water, what is the path of the trash in the model.What might happen to the trash in the water systems is discussed in the children’s meeting with the “What can I do” action cards. The cards describe problems that trash causes to animals.

- The Masters of Trash DiplomaAims: To empower children to understand and feel that they have learned and worked to maintain our varied and beautiful planet.Short description: The Masters of Trash Diploma is made from recycled materials. The diplomas are given to the children at the end of the project.

Appendix B

- Can you describe the types of nature experiences your family has had?

- What thoughts or feelings has the sustainable development project at the kindergarten sparked in you or other family members?

- Have any topics or activities related to the project come up in your child’s discussions or actions at home?

Appendix C

| Topic Question | Possible Clarification | Possible Follow-Up Question |

|---|---|---|

| The importance of nature Let’s first consider the significance of nature for your family. | ||

| (1a) Can you assess how much time your child spends in nature? | ||

| (1b) What does your child do in nature? | What does he/she see, hear, smell…? | |

| (1c) Do you feel that the time your child spends outdoors affects how he/she relates to nature? | How do you think it affects him/her? | |

| Play and activities Next, let’s talk about play. | ||

| (2a) Would you say that your child enjoys playing outside? | ||

| (2b) Does your child engage in nature-themed play, both indoors and outdoors? What kind? | Indoors, outdoors? | What kind? |

| (2c) How does your child participate in recycling at home? | Or in other nature-protective actions? | |

| (2d) What nature and recycling-related activities do you do together with your child? | ||

| (2e) What kind of experiences does the child have in protecting nature? | ||

| Knowledge and skills Let’s talk for a moment about your child’s recycling skills, or the skills to recycle things. | ||

| (3a) Can you describe your child’s recycling skills? | ||

| (3b) In your opinion, what significance do these skills have for the future? | ||

| (3c) Does your child talk about recycling? | What does he/she say? | |

| (3d) What kind of questions does your child ask about nature and its protection? | ||

| (3e) Does your child propose his/her own recycling ideas? | Like what could be recycled? Where could it be recycled? | |

| (3f) Let’s consider the following situation: an adult walking ahead drops an ice cream wrapper on the ground. They notice it but don’t pick up the litter. Your child sees the situation. What do you think will happen as a result of this experience? | What does the child say or do, or does he/she do anything? | |

| Future Let’s move forward towards the future. | ||

| (4a) What is your opinion on the statement that children need to be protected from dangers in nature and future threats? | ||

| Kindergarten Let’s consider your child’s kindergarten. | ||

| (5a) What role should the kindergarten play in matters related to protecting nature? | ||

| (5b) How would you improve the kindergarten’s activities and collaboration between families and the kindergarten in environmental matters? |

References

- Halkos, G.; Gkampoura, E.-C. Where Do We Stand on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals? An Overview on Progress. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 70, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2022: From Crisis to Sustainable Development, the SDGs as Roadmap to 2030 and Beyond; Sustainable development report; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-00-921008-9. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development. 2014. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000230514 (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Pramling Samuelsson, I.; Yoshie, I. The Contribution of Early Childhood Education to a Sustainable Society; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Global Waste Management Outlook; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/global-waste-management-outlook-2024 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Wilson, D.C.; Velis, C.A. Waste Management—Still a Global Challenge in the 21st Century: An Evidence-Based Call for Action. Waste Manag. Res. 2015, 33, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.M.-C.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Krueger, T.; Mishra, A.; Popp, A. The World’s Growing Municipal Solid Waste: Trends and Impacts. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 074021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, N.; Arnon, S.; Orion, N. Transforming Environmental Knowledge Into Behavior: The Mediating Role of Environmental Emotions. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Significant Life Experiences Revisited: A Review of Research on Sources of Environmental Sensitivity. J. Environ. Educ. 1998, 29, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, H.R.; Volk, T.L. Changing Learner Behavior Through Environmental Education. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 21, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.U. Experience-Based and Description-Based Perceptions of Long-Term Risk: Why Global Warming Does Not Scare Us (Yet). Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, J.A.; O’Connor, M. Environmental Education and Attitudes: Emotions and Beliefs Are What Is Needed. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W. Early Childhood Environmental Education: A Systematic Review of the Research Literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 31, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler Yıldız, T.; Öztürk, N.; İlhan İyi, T.; Aşkar, N.; Banko Bal, Ç.; Karabekmez, S.; Höl, Ş. Education for Sustainability in Early Childhood Education: A Systematic Review. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 796–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, L. The Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment. Harward Int. Law J. 1973, 14. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/28247/Stkhm_DcltnHE.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- United Nations. Report of the United Nations Conference on Human Environment. 1973. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/milestones/humanenvironment (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- UNESCO. Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education, Tbilisi, USSR, 14–26 October 1977: Final Report; 1977; p. 42. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000032763 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: From One Earth to One World; UN Documents: Gathering a Body of Global Agreements; UN: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987; Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Tilbury, D. Education for Sustainable Development: An Expert Review of Processes and Learning. 2011. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000191442 (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, T.; Barry, J. Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 733–739. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrable, A.; Booth, D. Increasing Nature Connection in Children: A Mini Review of Interventions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grindheim, L.T.; Bakken, Y.; Hauge, K.H.; Heggen, M.P. Early Childhood Education for Sustainability Through Contradicting and Overlapping Dimensions. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2019, 2, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedefalk, M.; Almqvist, J.; Östman, L. Education for Sustainable Development in Early Childhood Education: A Review of the Research Literature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggen, M.P.; Sageidet, B.M.; Goga, N.; Grindheim, L.T.; Bergan, V.; Krempig, I.W.; Utsi, T.A.; Lynngård, A.M. Children as Eco-Citizens? NorDiNa 2019, 15, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, C. Sowing the Seeds: Education for Sustainability within the Early Years Curriculum. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, J. Young Children’s Perceptions of Environmental Sustainability: A Maltese Perspective. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollweg, K.S.; Taylor, J.R.; Bybee, R.W.; Marcinkowsk, T.J.; McBeth, W.C.; Zoido, P. Developing a Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy; North American Association for Environmental Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: https://cdn.naaee.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/devframewkassessenvlitonlineed.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Lumber, R.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Beyond Knowing Nature: Contact, Emotion, Compassion, Meaning, and Beauty Are Pathways to Nature Connection. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsar, A. Young Children’s Ecological Footprint Awareness and Environmental Attitudes in Turkey. Child Ind. Res. 2021, 14, 1387–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihadi, D.W.; Sofia, H.; Yuliani, N.; Agus, S. The Effects of Green Schooling Knowledge Level and Intensity of Parental Guidance on the Environmental Awareness of the Early Age Student. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 12, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, P.; Roger-Loppacher, O.; Tintoré, M. Creating the Habit of Recycling in Early Childhood: A Sustainable Practice in Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnish National Agency of Education. National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care; Regulations and Guidelines 2018:3c; Finnish National Agency of Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2019.

- Sievänen, T.; Neuvonen, M. Luonnon Virkistyskäyttö 2010; The Finnish Forest Research Institute: Vantaa, Finland, 2011; Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-40-2331-6 (accessed on 16 October 2023).

- Institute for Economics & Peace Global Peace Index 2023: Measuring Peace in a Complex World. 2023. Available online: http://Visionofhumanity.Org/Resources (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- IQAir. 2023 World Air Quality Report. Region & City PM2.5 Ranking. 2023. Available online: https://www.iqair.com/dl/2023_World_Air_Quality_Report.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Lahti Region Waste Management Committee LAHTI Region Waste Management Regulations. 2023. Available online: https://salpakierto.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Lahti-region-waste-management-regulations-1.6.2023.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- European Commission; Directorate General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture; TNS Opinion & Social. Sport and Physical Activity: Executive Summary; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/599562 (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-134-20430-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects, 5th ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-335-26470-4. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, B.; Walker, R. Case-study and the Social Philosophy of Educational Research. Camb. J. Educ. 1975, 5, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4833-4437-9. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, J.; Hunter, A. Foundations of Multimethod Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-7619-8861-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dupin, C.M.; Borglin, G. Usability and Application of a Data Integration Technique (Following the Thread) for Multi- and Mixed Methods Research: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 108, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Ellis, J.; Alexander, V.D.; Cronin, A.; Dickinson, M.; Fielding, J.; Sleney, J.; Thomas, H. Triangulation and Integration: Processes, Claims and Implications. Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirri, K.; Nokelainen, P. Measuring Multiple Intelligences and Moral Sensitivities in Education; Moral Development and Citizenship Education; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 978-94-6091-758-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication; Qualitative Studies in Psychology; New York Univ. Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-8147-3294-6. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. The Use of Quotes in Qualitative Research. Res. Nurs. Health 1994, 17, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L.; Quincy, C.; Osserman, J.; Pedersen, O.K. Coding In-Depth Semistructured Interviews: Problems of Unitization and Intercoder Reliability and Agreement. Sociol. Methods Res. 2013, 42, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, A.J. From Data Management to Actionable Findings: A Five-Phase Process of Qualitative Data Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231183620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, T.; Lavonen, J.; Tirri, K. Self-Evaluated Multiple Intelligences of Gifted Upper-Secondary-School Physics Students in Finland. Roeper Rev. 2022, 44, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujaja, M.; Ojanperä, A.-M. Tapaustutkimus Laukaan Kasvatusprojektista: Vanhempien Käsityksiä Kasvatusvastuusta,-Arvoista Ja-Yhteistyöstä; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 1997; Available online: https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/10584 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Rantapohja Ylikiimingin Yhteisölliselle Kasvimaalle Merkittävä Apuraha. Rantapohja. 2020. Available online: https://www.rantapohja.fi/ylikiiminki/ylikiimingin-yhteisolliselle-kasvimaalle-merkittava-apuraha/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

| Dimension Item | Agree/ Strongly Agree | Disagree/ Strongly Disagree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Love for nature | |||

| 1. I enjoy walking in nature. | 15 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2. I enjoy the beauty and experiences related to nature. | 15 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nature conservation | |||

| 3. Animal rights are important to me. | 14 (93%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7%) |

| 4. I take part in projects and events related to protection of the environment. | 1 (7%) | 12 (80%) | 2 (13%) |

| 5. Protecting nature is important to me. | 11 (73%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (27%) |

| Environment-friendly consumer habits | |||

| 6. I pay attention to my consumption habits to protect the environment. | 7 (47%) | 1 (7%) | 7 (47%) |

| 7. I am ready to pay more for the products that are environmentally friendly than for normal products. | 8 (53%) | 3 (20%) | 4 (27%) |

| 8. I am active in recycling. | 8 (53%) | 1 (7%) | 6 (40%) |

| 9. I sort different trash at home appropriately. | 13 (87%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (13%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sihvonen, P.; Lappalainen, R.; Herranen, J.; Aksela, M. Promoting Sustainability Together with Parents in Early Childhood Education. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050541

Sihvonen P, Lappalainen R, Herranen J, Aksela M. Promoting Sustainability Together with Parents in Early Childhood Education. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(5):541. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050541

Chicago/Turabian StyleSihvonen, Pilvi, Riikka Lappalainen, Jaana Herranen, and Maija Aksela. 2024. "Promoting Sustainability Together with Parents in Early Childhood Education" Education Sciences 14, no. 5: 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050541

APA StyleSihvonen, P., Lappalainen, R., Herranen, J., & Aksela, M. (2024). Promoting Sustainability Together with Parents in Early Childhood Education. Education Sciences, 14(5), 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050541