Views of Parents on Using Technology-Enhanced Toys in the Free Play of Children Aged One to Four Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Digital Technology and Play

3. Digital Play and Parents’ Perspectives

Greek ECEC Sector

- What do parents think about using digital technologies and the use of technology-enhanced toys for children between ages one and four?

- What advantages or disadvantages do parents report being associated with their young children (1–4-year-old) using technology-enhanced toys?

4. Method

4.1. Participants

4.2. Statistical Analysis

Selection of the Technology-Enhanced Toys

- Fisher-Price Linkimals Owl Light Up and Learn (ages 18+ months). Toddlers engage with Owl’s circle of buttons to initiate a multi-sensory experience featuring lights, sounds, and an array of educational songs and phrases. By exploring this interactive feature, users—particularly children—can trigger many stimulating responses, fostering a dynamic and engaging learning environment. The circle of buttons serves as a gateway to a diverse range of auditory and visual stimuli, enhancing the overall interactive and educational value of the owl’s design (https://www.amazon.com/Fisher-Price-Linkimals-Light-Up-Interactive-Learning/dp/B09NP97B3Q, accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Fisher-Price Laugh & Learn Baby to Toddler Toy Let’s Connect Laptop Pretend Computer with Smart Stages (Ages 6+ Months). The Laugh & Learn Let’s Connect Laptop electronic toy by Fisher-Price offers an engaging play and learning experience for babies, whether at home or on the go. Featuring pretend video chats with Puppy and friends, along with interactive elements like sliding to ‘unmute’, babies can explore pressing buttons on the keyboard or spinning the musical roller. These actions activate vibrant multi-colour lights, and the toy introduces over 55 songs, sounds, and phrases covering topics such as the alphabet, colours, and counting. With three Smart Stages levels, parents can adapt the learning content to suit their little one’s developmental stage, ensuring a customised and evolving educational experience as the child grows (https://www.amazon.com/Fisher-Price-Connect-Electronic-Learning-Toddlers/dp/B09BDBKXFQ, accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Beebot (ages 3+ years). BeeBot, with its user-friendly design, can be easily programmed using on-board buttons, allowing precise movement in space. Children can program it to move forwards or backwards or turn left or right. This simple yet effective interface serves as an excellent introduction for teaching young children concepts of control, direction, and programming language. BeeBot provides a hands-on and accessible way for kids to engage with programming principles, making it an ideal starting point for fostering early learning of these essential skills (https://www.amazon.com/TTS-Bee-Bot-Programmable-Educational-Rechargeable/dp/B086HFXDSM/ref=sr_1_5?crid=3QMDLKHOBIVBA&keywords=bee+bot&qid=1705682423&sprefix=bee+bot%2Caps%2C218&sr=8-5, accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Coko Kids Entry-Level Programmable Crocodile Robot (ages 3+ years). Coko, the adorable programmable crocodile, is thoughtfully designed to offer younger children a playful introduction to coding. Geared towards kids aged three and older, Coko provides an entertaining game where children can freely move their new friend or attempt to reach a specific goal. In either scenario, children learn fundamental programming concepts in a fun and straightforward manner. This engaging experience serves as an accessible and enjoyable way for young learners to grasp the basics of coding, fostering early interest and understanding in this important skill (https://www.amazon.de/-/en/Programmable-Crocodile-Electronic-Educational-Clementoni/dp/B07PLD4V71, accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Lexibook Power Puppy: My Programmable Smart Robot Dog (ages 3+ years). Power Puppy is an advanced robot dog equipped with gesture control. This cutting-edge robotic companion offers a plethora of interactive games, featuring sound and light effects, dynamic movements, barking, animal imitations, and more. Designed not only for entertainment but also as an educational tool, Power Puppy serves as an avenue to introduce young users to programming. Using the remote control, children can command Power Puppy, providing an engaging platform to explore fundamental programming concepts. This not only ensures a captivating play experience but also lays the groundwork for a comprehensive understanding of programming principles in an accessible manner (https://www.amazon.com/LEXiBOOK-Power-Puppy-Programmable-Rechargeable/dp/B09DYFQP63?th=1, accessed on 2 September 2022).

5. Procedure

6. Results

6.1. Association between Variables: First Questionnaire

6.2. Association between Variables: Second Questionnaire

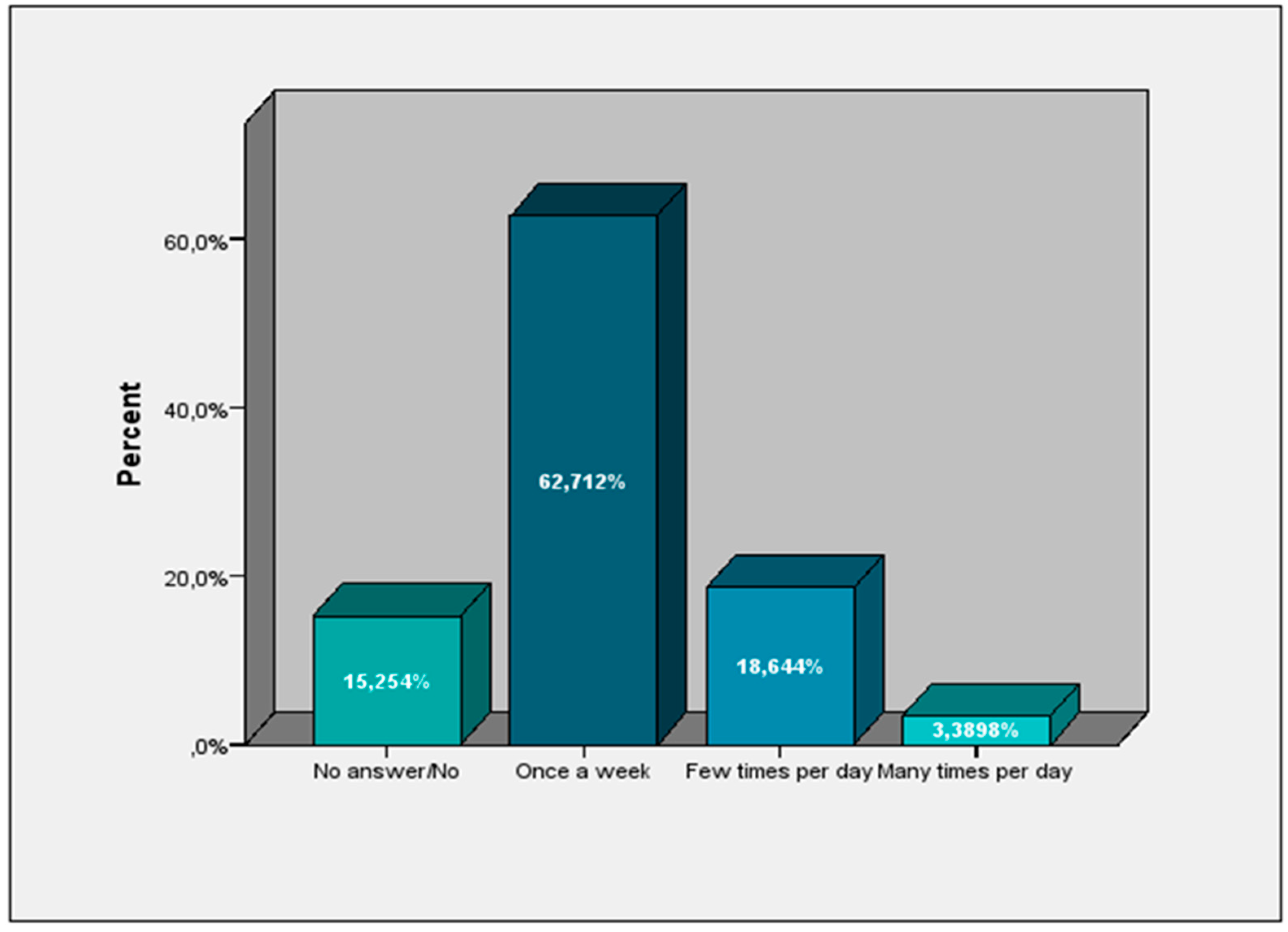

6.3. Children’s References to Their Experiences with the TETs

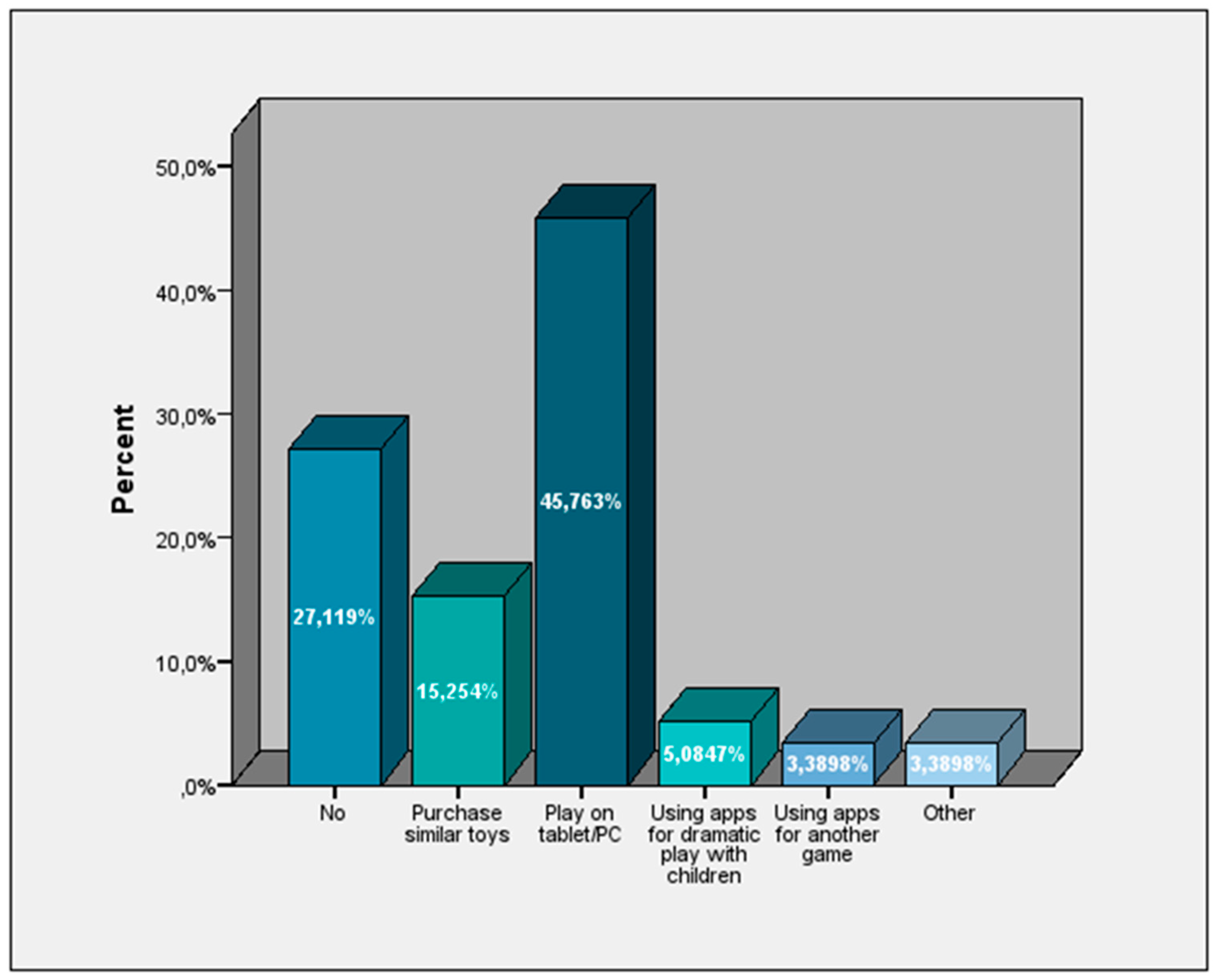

6.4. Parents’ Use of Children’s References to Technologically Enhanced Toys

- Speech/Vocabulary;

- Gross motor activity (Gross motor activity refers to a child’s ability to control large muscles of the body or muscle groups to move each limb individually (e.g., arm, leg movement) or in a coordinated manner (e.g., walking, running);

- Fine manipulation (the child’s ability to manipulate small muscles correctly—using the muscles in the hands, fingers, and wrists in any action, e.g., holding a pencil);

- Social-emotional development (development of the child’s personality, understanding of his/her feelings and the feelings of others, expression and management of his/her needs and desires);

- Mathematical concepts;

- Creativity;

- Communication;

- Science concepts (developing manual and scientific skills);

- Other—they could write their own answer.

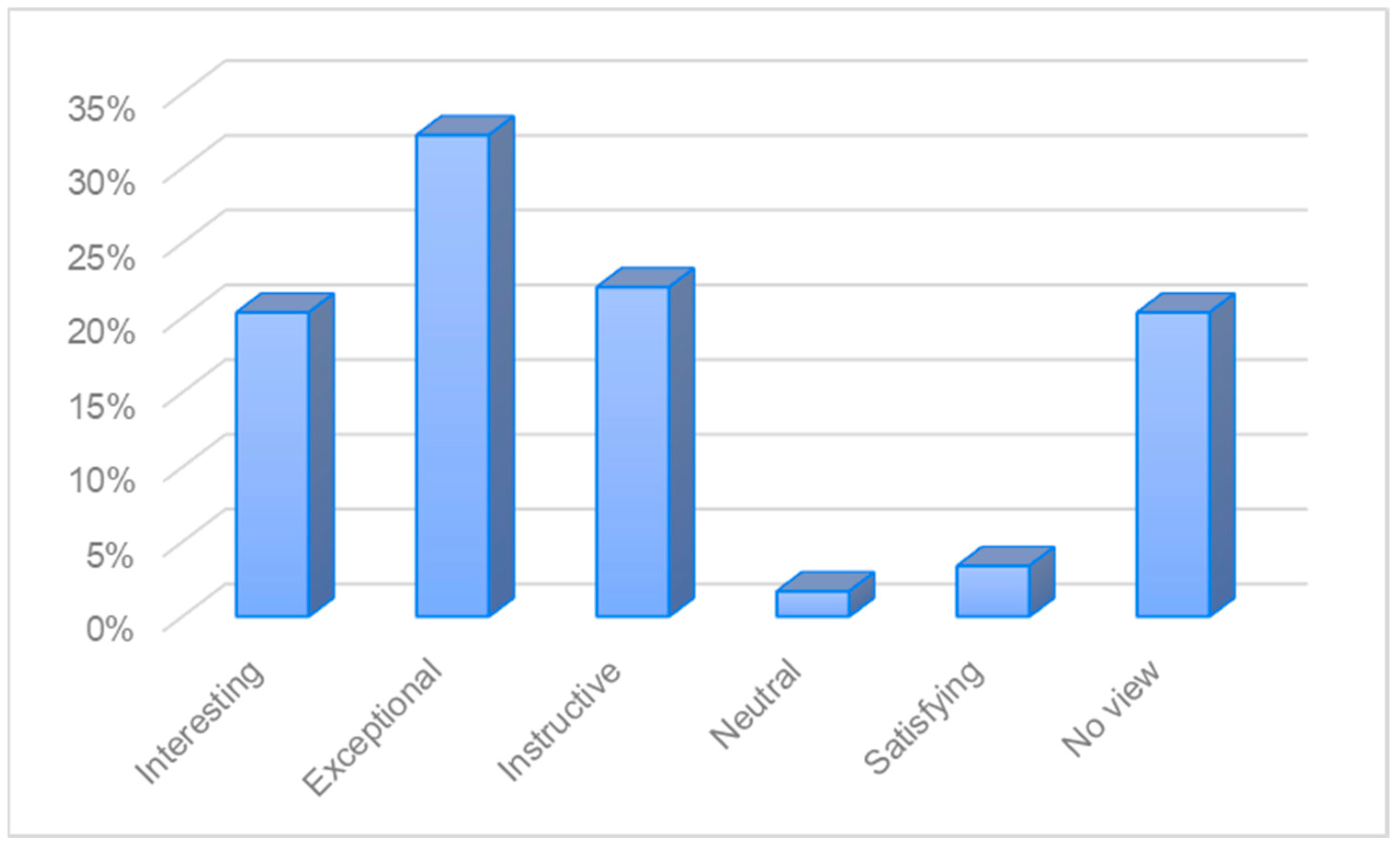

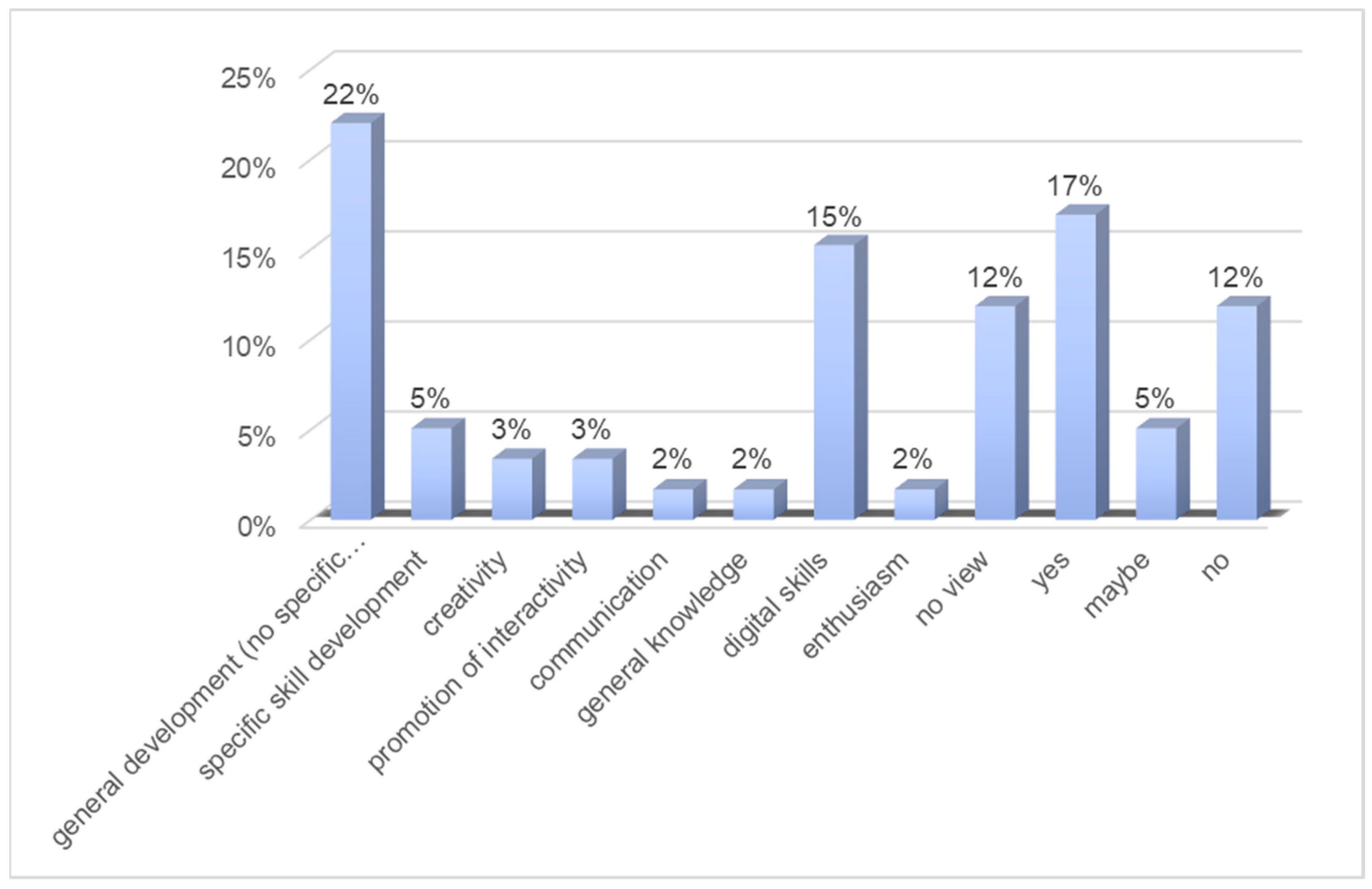

6.5. Open-Ended Questions

- ‘I’m unsure if I am using it correctly.’

- ‘Limited discussion of digital play within the household.’

- ‘My concern stems from the child’s complete absence of any mention or discussion of digital play, as if it was never a part of their experience.’

- I prefer not to introduce digital games at such a young age.’

7. Discussion

8. Recommendations for Future Research

9. Limitations

10. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Percentage in Pre-Questionnaire (n = 78) | Percentage in Post-Questionnaire (n = 59) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 20–30 | 7.7 | 8.5 |

| 30–40 | 59 | 66.1 |

| 40–50 | 33.3 | 25.4 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 19.2 | 13.6 |

| Female | 80.8 | 86.4 |

| Education | ||

| LEA/VAS 1 | 2.6 | 5.1 |

| General High School | 20.5 | 16.9 |

| Vocational High School | 10.3 | 5.1 |

| Technological educational institution | 25.6 | 22.0 |

| University | 16.7 | 22.0 |

| MSc | 23.1 | 20.3 |

| PhD | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| Other | 0.0 | 6.8 |

| Occupation | ||

| Public/municipal employee | 21.8 | 11.9 |

| Private employee | 51.3 | 57.6 |

| Freelancer | 15.4 | 18.6 |

| Unemployed | 11.5 | 11.9 |

| Number of Children | ||

| 1 | 41 | 40.7 |

| 2 | 55.1 | 52.5 |

| 3 | 3.8 | 6.8 |

| Age of Family’s First Child (Years) | ||

| 0–1 | 1.3 | - |

| 1–2 | 17.9 | 6.8 |

| 2–3 | 11.5 | 13.6 |

| 3–4 | 32.1 | 35.6 |

| 4–6 | 19.2 | 27.1 |

| 6 or more | 17.9 | 16.9 |

| Age of Family’s Second Child (Years) | ||

| 0–1 | 6.4 | 11.9 |

| 1–2 | 5.1 | 8.5 |

| 2–3 | 15.4 | 13.6 |

| 3–4 | 14.1 | 20.3 |

| 4–6 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| 6 or more | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| Age of Family’s Third Child (Years) | ||

| 0–1 | - | 1.7 |

| 1–2 | 2.6 | 3.4 |

| 4–6 | - | 1.7 |

| Number of Children Participating | ||

| 1 | 98.7 | 94.9 |

| 2 | 1.3 | 5.1 |

| Age of First Child Participating (Years) | ||

| 0–1 | 1.3 | - |

| 1–2 | 20.5 | 8.5 |

| 2–3 | 29.5 | 23.7 |

| 3–4 | 47.4 | 55.9 |

| 4–5 | 1.3 | 11.9 |

| Age of Second Child Participating (Years) | ||

| 1–2 | 1.3 | 3.4 |

| 2–3 | - | 1.7 |

| Parent Demographic | Importance of Child’s Use of DT |

|---|---|

| Occupation | 0.034 |

| Number of Children | 0.018 |

| First Child’s Digital Technology Use | Second Child’s Digital Technology Use | Importance of Digital Technology Use by the Child | Child’s Report on Toy Use Frequency | Using Children’s References to Toys at Home | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents’ Educational level | - | - | 0.011 | 0.034 | 0.032 |

| Number of children in the family | 0.041 | - | - | - | - |

| First child’s age | - | 0.023 | - | - | - |

References

- Walker, S.; Hatzigianni, M.; Danby, S.J. Electronic Gaming: Associations with Self-Regulation, Emotional Difficulties and Academic Performance. In Digital Childhoods; Danby, S.J., Fleer, M., Davidson, C., Hatzigianni, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; Volume 22, pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lowery, T. The Impact of Digital Technology on Children’s Social Interaction: A Literature Review. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368751706_The_Impact_of_Digital_Technology_on_Children’s_Social_Interaction_A_Literature_Review (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Gillen, J.; Kucirkova, N. Percolating Spaces: Creative Ways of Using Digital Technologies to Connect Young Children’s School and Home Lives. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Brito, R.; Ribbens, W.; Daniela, L.; Rubene, Z.; Dreier, M.; Gemo, M.; Di Gioia, R.; Chaudron, S. The Role of Parents in the Engagement of Young Children with Digital Technologies: Exploring Tensions between Rights of Access and Protection, from ‘Gatekeepers’ to ‘Scaffolders’. Glob. Stud. Child. 2016, 6, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowman, L.; McPake, J.; Stephen, C. Just Picking It up? Young Children Learning with Technology at Home. Camb. J. Educ. 2008, 38, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, C.; Plowman, L. Digital Technologies Play and Learning. ECF 2013, 17, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.E.; Christie, J.F. Play and Digital Media. Comput. Sch. 2009, 26, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J.; Plowman, L.; Yamada-Rice, D.; Bishop, J.; Scott, F. Digital Play: A New Classification. Early Years 2016, 36, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Joint Research Centre. Young Children (0–8) and Digital Technology: A Qualitative Study across Europe; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T., Gottschalk (Ed.) OECD Educating 21st Century Children: Emotional Well-Being in the Digital Age; Educational Research and Innovation; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.L.; Paciga, K.A.; Danby, S.; Beaudoin-Ryan, L.; Kaldor, T. Looking beyond Swiping and Tapping: Review of Design and Methodologies for Researching Young Children’s Use of Digital Technologies. Cyberpsychology 2017, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Play-Based Learning: Digital Play | Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. Available online: https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/play-based-learning/according-experts/digital-play (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Hargraves, V. What Is Digital Play? Available online: https://theeducationhub.org.nz/what-is-digital-play/ (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Kewalramani, S.; Arnott, L.; Dardanou, M. Technology-Integrated Pedagogical Practices: A Look into Evidence-Based Teaching and Coherent Learning for Young Children. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 28, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowman, L. Digital Play; Centre for Research in Digital Education, University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mascheroni, G.; Holloway, D. (Eds.) Introducing the Internet of Toys. In The Internet of Toys; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.-N.; Kuo, V.; King, C.-T.; Chang, C.-P. Internet of Toys: An e-Pet Overview and Proposed Innovative Social Toy Service Platform. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Computer Symposium (ICS2010), Tainan, Taiwan, 16–18 December 2010; IEEE: Tainan, Taiwan, 2010; pp. 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, L.; Yelland, N.; Hatzigianni, M.; Dickson-Deane, C. The Use of Internet of Things Devices in Early Childhood Education: A Systematic Review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 6333–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heljakka, K.; Ihamäki, P. Toys That Mobilize: Past, Present and Future of Phygital Playful Technology. In Proceedings of the Future Technologies Conference (FTC) 2019, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–25 October 2019; Arai, K., Bhatia, R., Kapoor, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 625–640. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J. Technology and Play; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Kim, M.; Palkar, J. Using Emerging Technologies to Promote Creativity in Education: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2022, 3, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergen, D.; Hutchinson, K.; Nolan, J.T.; Weber, D. Effects of Infant-Parent Play with a Technology-Enhanced Toy: Affordance-Related Actions and Communicative Interactions. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2009, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komis, V.; Karachristos, C.; Mourta, D.; Sgoura, K.; Misirli, A.; Jaillet, A. Smart Toys in Early Childhood and Primary Education: A Systematic Review of Technological and Educational Affordances. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, L.; Palaiologou, I.; Gray, C. Digital Devices, Internet-enabled Toys and Digital Games: The Changing Nature of Young Children’s Learning Ecologies, Experiences and Pedagogies. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.I.; Khan, N.; Raza, H.; Imran, A.; Ismail, F. Digital Technologies in Education 4.0. Does It Enhance the Effectiveness of Learning? A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2021, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auxier, B.; Anderson, M.; Perrin, A.; Turner, E. Parenting Children in the Age of Screens; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S. Digital Play in the Early Years: A Contextual Response to the Problem of Integrating Technologies and Play-Based Pedagogies in the Early Childhood Curriculum. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 21, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelland, N. Knowledge Building with ICT in the Early Years of Schooling. He Kupu 2011, 2, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Reid Chassiakos, Y.; Radesky, J.; Christakis, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Cross, C.; Council on Communications and Media; Hill, D.; Ameenuddin, N.; Hutchinson, J.; Levine, A.; et al. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhafeeri, F.; Palaiologou, I.; Folorunsho, A. Integration of Digital Technologies into Play-Based Pedagogy in Kuwaiti Early Childhood Education: Teachers’ Views, Attitudes and Aptitudes. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2016, 24, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J.; Plowman, L.; Yamada-Rice, D.; Bishop, J.; Lahmar, J.; Scott, F. Play and Creativity in Young Children’s Use of Apps. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verenikina, I.; Kervin, L. iPads, Digital Play and Preschoolers. He kupu 2011, 2, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Palaiologou, I. Children under Five and Digital Technologies: Implications for Early Years Pedagogy. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 24, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technology and Young Children in the Digital Age|Digital Skills and Jobs Platform. Available online: https://digital-skills-jobs.europa.eu/en/community/online-discussions/technology-and-young-children-digital-age (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Arnott, L. An Ecological Exploration of Young Children’s Digital Play: Framing Children’s Social Experiences with Technologies in Early Childhood. Early Years 2016, 36, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oργανωτικές Διαφοροποιήσεις Και Εναλλακτικές Δομές Στην Προσχολική Εκπαίδευση Και Φροντίδα [Organizational Variations and Alternative Structures in Early Childhood Education and Care]. Available online: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/el/national-education-systems/greece/organotikes-diaforopoiiseis-kai-enallaktikes-domes-stin (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Government of Greece. Decisions. Government Gazette, 8 February 2023. Available online: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/publications/docs2023/FEK-2023-Tefxos_B-00602-08_02_2023.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Ahmadzadeh, Y.I.; Lester, K.J.; Oliver, B.R.; McAdams, T.A. The Parent Play Questionnaire: Development of a Parent Questionnaire to Assess Parent–Child Play and Digital Media Use. Soc. Dev. 2020, 29, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isikoglu Erdogan, N.; Johnson, J.E.; Dong, P.I.; Qiu, Z. Do Parents Prefer Digital Play? Examination of Parental Preferences and Beliefs in Four Nations. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, S.; Mascheroni, G.; Dreier, M.; Chaudron, S.; Lagae, K. How Parents of Young Children Manage Digital Devices at Home: The Role of Income, Education and Parental Style; EU Kids Online, LSE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Konca, A.S. Digital Technology Usage of Young Children: Screen Time and Families. Early Childhood Educ. J. 2022, 50, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, S.A.; Al-Shboul, M.; Tannous, A.; Banat, S.; Aldreabi, H. Young Children’s Use of Technological Devices: Parents’ Views. MAS 2019, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo Martinez, N.; Xerxa, Y.; Law, J.; Serdarevic, F.; Jansen, P.W.; Tiemeier, H. Double Advantage of Parental Education for Child Educational Achievement: The Role of Parenting and Child Intelligence. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, S.F.; Casanova, S.M.; Delisle, J.H. Back-and-Forth Conversation during Parent–Child Co-Use of an Educational App Game. Early Child Dev. Care 2023, 193, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, K. The Impact of Parental Confidence in Using Technology on Parental Engagement in Children’s Education at Home during COVID-19 Lockdowns: Evidence from 19 Countries. SN Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apdillah, D.; Simanjuntak, C.R.A.; Napitupulu, C.N.S.B.; Sirait, D.D.; Mangunsong, J. The role of parents in educating children in the digital age. ROMEO 2022, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapella, O.; Schmidt, E.M.; Vogl, S. Integration of Digital Technologies in Families with Children Aged 5–10 Years: A Synthesis Report of Four European Country Case Studies; COFACE Families Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radesky, J.S.; Christakis, D.A. Increased Screen Time. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 63, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafton, T.; Holmarsdottir, H.B.; Kapella, O.; Sisask, M.; Zinoveva, L. Children’s Vulnerability to Digital Technology within the Family: A Scoping Review. Societies 2022, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivrikova, N.; Nemudraya, E.; Gilyazeva, N.; Gnatyshina, E.; Moiseeva, E. The Sibling as a Factor of Parental Control over the Use of Gadgets by Children. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 119, 05001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, R.A.; Zimmermann, L. Coviewing, Scaffolding, and Children’s Media Comprehension. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Psychology; Bulck, J., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tsinivits, D.; Unsworth, S. The Impact of Older Siblings on the Language Environment and Language Development of Bilingual Toddlers. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2021, 42, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowman, L.; McPake, J. Seven Myths About Young Children and Technology. Child. Educ. 2013, 89, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartella, E.A.; Jennings, N. Children and Computers: New Technology. Old Concerns. Future Child. 2000, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucirkova, N.; Radesky, J. Digital Media and Young Children’s Learning: How Early Is Too Early and Why? Review of Research on 0–2-Year-Olds. In Education and New Technologies; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K.L.; Howard, S.J.; Verenikina, I.; Kervin, L.K. Parent Perspectives on Young Children’s Changing Digital Practices: Insights from Covid-19. J. Early Child. Res. 2023, 21, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikken, P.; de Haan, J. Guiding Young Children’s Internet Use at Home: Problems That Parents Experience in Their Parental Mediation and the Need for Parenting Support. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2015, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollarolo, E.; Papavlasopoulou, S.; Granone, F.; Reikerås, E. Play with Coding Toys in Early Childhood Education and Care: Teachers’ Pedagogical Strategies, Views and Impact on Children’s Development. A Systematic Literature Review. Entertain. Comput. 2024, 50, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talves, K.; Kalmus, V. Gendered Mediation of Children’s Internet Use: A Keyhole for Looking into Changing Socialization Practices. Cyberpsychology 2015, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S. Sample Size Determination (for Descriptive Analysis). Int. J. Curr. Res. 2017, 9, 48365–48367. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, W.; Parent, J.; Forehand, R.; Sullivan, A.D.W.; Jones, D.J. Parental Perceptions of Technology and Technology-Focused Parenting: Associations with Youth Screen Time. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 44, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Frequency of Use (Hours per Week) | Percentage in Pre-Questionnaire (n = 78) | Percentage in Post-Questionnaire (n = 59) |

|---|---|---|

| First Child | ||

| Not at all | 5.1 | 6.8 |

| Little (1–2) | 5.1 | 37.3 |

| Enough (2–3) | 43.6 | 30.5 |

| Much (5–6) | 26.9 | 15.3 |

| Very much (8–10) | 19.2 | 10.2 |

| Second Child | ||

| Not at all | 1.3 | 5.1 |

| Little (1–2) | 2.6 | 8.5 |

| Enough (2–3) | 2.6 | 10.2 |

| Much (5–6) | 1.3 | - |

| Very much (8–10) | - | 5.1 |

| Significance of First Child’s Use of DT | ||

| Almost not significant | 5.1 | 3.4 |

| Slightly significant | 20.5 | 10.2 |

| Neutral | 24.4 | 33.9 |

| Very significant | 29.5 | 27.1 |

| Extremely significant | 20.5 | 25.4 |

| No Answer | Speech/ Vocabulary | Fine-Motor Skills | Social-Emotional Development | Creativity | Communication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 10 | 15 | 16 | 5 | 10 | 2 |

| Percent | 16.9 | 25.4 | 27.1 | 8.5 | 16.9 | 3.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bourha, D.; Hatzigianni, M.; Sidiropoulou, T.; Vitoulis, M. Views of Parents on Using Technology-Enhanced Toys in the Free Play of Children Aged One to Four Years. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050469

Bourha D, Hatzigianni M, Sidiropoulou T, Vitoulis M. Views of Parents on Using Technology-Enhanced Toys in the Free Play of Children Aged One to Four Years. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(5):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050469

Chicago/Turabian StyleBourha, Dimitra, Maria Hatzigianni, Trifaini Sidiropoulou, and Michael Vitoulis. 2024. "Views of Parents on Using Technology-Enhanced Toys in the Free Play of Children Aged One to Four Years" Education Sciences 14, no. 5: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050469

APA StyleBourha, D., Hatzigianni, M., Sidiropoulou, T., & Vitoulis, M. (2024). Views of Parents on Using Technology-Enhanced Toys in the Free Play of Children Aged One to Four Years. Education Sciences, 14(5), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050469