Abstract

The framework plan for kindergartens in Norway emphasizes knowledge of Indigenous Sámi culture among the core values of pedagogical practice. Preservice students in early childhood teacher education (ECTE) are thus obliged to learn about Sámi culture. We explored and developed collaborative teaching interventions for Sámi topics. We aimed to “braid” Sámi diversity into our teaching and make the lessons explorative, practical, and student-active, in line with the basics of Sámi pedagogy. The teaching emphasized how Sámi people were historically connected to the land through sustainable livelihoods and respect for natural resources. We developed the teaching interventions through action-based research in three cycles (2022–2024). Our primary material consisted of students’ responses to online surveys and group interviews. The findings show that students gained a broader understanding of diversity within Sámi culture after the interventions. They reported greater interest and better learning outcomes, especially from the active and practical lessons. The Sámi teaching content, structure, and methods explored in this study may be relevant to other ECTE or other teacher education programs, especially those related to teaching Indigenous topics to majority populations.

1. Introduction

Recently, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Norway released a report about injustice to the Indigenous Sámi people due to the state’s Norwegianization policy []. According to the report, the general population lacks knowledge of the Sámi, which must be addressed through education and other actions. All kindergarten teachers are obliged to highlight Sámi culture to ensure that children develop respect for the diversity of Sámi culture [,]. Moreover, if Sámi children are present in a kindergarten, Sámi language and culture must be part of the pedagogical practice, regardless of their place of residence in Norway []. This implies that preservice students (hereafter called students) in early childhood teacher education (ECTE) must learn about the diversity that characterizes Sámi culture to provide extra support for the cultural formation of Sámi children while maintaining a general focus on all children [,]. According to another report, the Sámi culture is mainly emphasized in Norwegian kindergartens during the period around Sámi National Day (6 February) []. Kindergarten teachers claim they lack the expertise to incorporate Sámi topics into their teaching throughout the year and that their priorities lie elsewhere [].

In our work as ECTE teachers, we must make choices about what kind of teaching content and pedagogical approaches we convey. We both have a coastal Sámi heritage, hailing from a fjord close to where we are based in Tromsø in the central part of Sápmi (land of the Sámi) (Figure 1). Our family stories are marked by the colonial Norwegianization process [] and diverge somewhat from the typical representation of Sámi culture, which is associated with reindeer herding, lavvu (Sámi tents), and traditional colorful clothing (e.g., from a Google search for “Sámi culture”). Against this backdrop, in this article, we discuss how to collaboratively develop teaching interventions that (1) explore the diversity within Sámi culture and (2) engage students using teaching methods guided by Sámi pedagogy [].

Figure 1.

Sápmi (the land of the Sámi people), which includes northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula in Russia (highlighted in blue).

1.1. The Indigenous Sámi People of Norway

Historically, the Sámi people have lived in Sápmi, which includes the northern part of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula in Russia (Figure 1). Nowadays, the Sámi live modern lives in cities and towns across and outside Scandinavia, and an increasing number of people recognize their Sámi family heritage []. The Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169) recognizes the Sámi as indigenous to Norway [], granting them the legal right to sustain and develop their cultural identity, language, traditions, and institutions. However, most Sámi people, especially those living in coastal areas, have lost their language and identity due to the Norwegian government’s Norwegianization policy during the period 1850–1960 [,]. Moreover, knowledge of Sámi diversity and the Sámi people’s relationships with traditional habitation areas has largely been lost [].

The geography of the land, waterways, flora and fauna, climate, seasonal changes, and weather conditions affect the Sámi peoples’ daily lives, livelihood, traditions, and crafts. Sámi traditions are rooted in respect of the use of natural resources [,], deep knowledge of how, when, and where to find and prepare food [], food culture [], and the acknowledgment of their relationship with the spiritual dimension of nature and sustainability [,]. For example, coastal Sámi people were traditionally fishermen, farmers, and hunter-gatherers, sharing knowledge and practices with their Norwegian (and Kven) neighbors []. Consequently, Sámi and Norwegian livelihood traditions were similar. Even today, most Sámi claim to have a practical and relational connection to nature [] and their ancestral land [].

Sámi culture is currently undergoing a revitalization process, with Sámi traditions and practices integrated into education [], and influenced by modern cultures and technologies [,]. To preserve core values such as holistic perspectives on sustainability and the recognition of diversity within Sámi culture, we must acknowledge the interdependence between people and nature [,], and we should embrace Sámi approaches to learning.

1.2. Sámi and Indigenious Ways of Learning

Sámi pedagogy, which encompasses Sámi ways of thinking, knowing, and doing, was born of holistic, active, and contextual relational learning processes in or with nature [,]. This is in line with other Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies [,,,]. Sámi pedagogy builds on the transmission of traditional knowledge (árbediethu) and skills (árbemáhttu) [] for survival (birgejupmi) and Sámi child rearing, which honors mutual togetherness and connectedness (ovttastallan) [], fostering independence (iešbirgejeaddji), [] and creating space for transmitting cultural knowledge to the new generations (searvelatnja) [,]. In Sámi society, the relationship with the land and people is highlighted through kinship, family relations, and reciprocal friendships (verddet) []. This is based on a holistic learning approach grounded in the confidence that children will learn at their own pace through guidance and support from other beings and/or through experience [].

Keskitalo and Määttä compared approaches to Sámi pedagogy with Western education []. The main principles of Sámi pedagogy are that the learner is active, independent, and flexible, while the teacher has an advisory, directive, and supportive role rather than merely imparting knowledge to a passive class. The Sámi curriculum is locally adapted to Sámi culture, community, and relations with nature. The learning processes are collaborative and cyclic (in terms of time) and often take place outdoors (in extended classrooms) []. Similarly, other Indigenous learning design principles are based on holistic conceptions of reality that integrate society and nature, emphasizing learner engagement and highlighting sustainability-oriented pedagogies [,,].

Sámi ways of learning may be applied to the majority population, and the strategy for implementing this approach in Norway takes teacher education as a starting point [].

1.3. Approaches to Integrating Sámi Content into Teacher Education

Teaching the majority population Sámi topics in educational contexts can be challenging and risky [,]. This is due to Norway’s colonization history, a lack of knowledge, and the risk of reproducing stereotypical views or “othering” the Sámi due to ignorance. Consequently, this endeavor may require the indigenization of teacher education as a culture-sensitive and inclusive approach [].

The indigenization and decolonization of education are aimed at reclaiming or revitalizing Indigenous spaces, methods, and voices [,]. Decolonization emphasizes the critical and deconstructive dimensions of the impact of colonialism on Indigenous communities, while indigenization is based on an approach aimed at making and remaking Indigenous perspectives visual and active []. However, we must be aware of the risk of “whitestreaming” Indigenous teaching content [,]—that is, presenting Indigenous cultures from the perspective of mainstream society [].

Recently, the notion of ‘braiding’ Indigenous and scientific knowledge systems together has been suggested as a means of finding new and better solutions, for instance, regarding sustainability issues [,,]. Braiding knowledge is a relational process that interconnects dimensions of time, place, values, generations, landscapes, storytelling, and tradition—a process in which everything is interrelated, including from a Sámi perspective []. In Norway, Eriksen et al. developed a reflection tool for working with Sámi and other Indigenous perspectives in teacher education [], which may be helpful in conveying knowledge to the majority population. Our work is based on braiding principles, which means that each thread to be braided must be acknowledged and sustained. Accordingly, we use the Sámi word nannet, which means “to strengthen or acknowledge something”. We nannet the diversity within Sámi culture through braiding instead of using the term “indigenization”, as it may carry connotations of “Sámification”, which are not applicable to the majority population.

1.4. ECTE in Norway

ECTE in Norway is a three-year bachelor’s program that is nationally regulated through a framework plan that includes goals, content, and learning outcomes for teaching in early childhood education []. Paragraph 1, item 9, states that the curriculum should include an understanding of Sámi culture as part of the national culture and emphasize the status and rights of Indigenous peoples both nationally and internationally []. The study plan is structured differently at each educational institution, with different directions for reinforcement and professional development of teaching topics—for instance, reinforcing a course on nature, health, play, and learning (this research).

1.5. Aim of the Study

The aim of this study was to devise collaborative teaching interventions that broaden students’ perspectives on the diversity of Sámi culture and align the lessons more with Sámi pedagogy. We developed these interventions based on students’ feedback and our own self-assessments (evaluation, reflection, and replanning). In this study, we addressed the following research questions: (1) What in the teaching interventions contributes to students’ knowledge of and interest in Sámi diversity? (2) How can Sámi pedagogical approaches be integrated into our teaching?

2. Materials and Methods

This research was inspired by action research and pedagogical research, which aim to improve and further develop the teaching practice [,]. Action research is a cyclic process with four steps: (1) planning, (2) execution, (3) observation and evaluation, and (4) reflection to plan an improved cycle [,]. In the course of three years (cycles), we aimed to improve our teaching about Sámi culture with a participatory design that included student voices.

The teaching interventions (sessions) were administered to three ECTE student groups in their fourth semester (spring) in the Nature, Health, Play, and Learning course. To develop collaborative teaching, our point of departure was the disciplines of food and health (first author) and natural science (second author).

2.1. Participants

This study adhered to the ethical standards set by the National Research Ethics Committees [] and was approved by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. All students attending the ECTE course for all three years were asked to participate in the online survey through informed consent at the beginning of the survey. A total of 23 of 32 students (72%) agreed to participate in 2022, 20 of 25 students (80%) agreed to participate in 2023, and 7 of 9 students (78%) agreed to participate in 2024. We did not collect data on gender, age, or other demographics since they were not relevant to our research. Moreover, although we became aware that some students were of Sámi origin, we did not ask about their ethnic background.

2.2. The Teaching Cycles

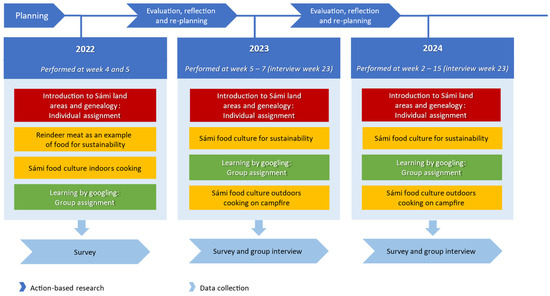

We developed the teaching interventions through three action research cycles over three years (2022–2024) based on the students’ evaluations and our own reflections (Figure 2). In the following, we outline the overall structure of the teaching interventions and the collection of data.

Figure 2.

Overview of the action-based research on teaching content (red, yellow, and green) and collection of data (light blue) from different student groups in 2022, 2023, and 2024. The teaching sessions are marked in boxes: “Sámi land areas and genealogy” (second author, red), “Sámi food culture” (first author, yellow), and “learning by googling (LBG)” (second author, green).

The first year (2022) was part of the second author’s pedagogical development project in a mandatory course that was a prerequisite for teaching in higher education []. That year, the teaching sessions were held as single-discipline subjects (Figure 2). The teaching consisted of one session (45 min) about “Sámi land areas and genealogy” (second author), two sessions (2 × 90 min) with “Sámi food culture” (first author), and one session (135 min) on “learning by googling (LBG)” (second author). The sessions took place over a period of two weeks and were partly held online due to restrictions related to the COVID-19 outbreak. The LBG session consisted of group assignments (90 min) related to various Sámi topics that the students explored through googling, reflected upon, and presented (5 min each group) to the class at the end of the session. The online survey in 2022 revealed that the group assignment LBG on self-selected Sámi topics was perceived as positive overall. This inspired us to collaborate in 2023 to improve our teaching in our joint ECTE course through action-based research (Figure 2). We saw this as an opportunity to convey our own Sámi cultural heritage to enliven coastal Sámi cultural perspectives.

In 2023, we jointly held the LBG session, wearing traditional Sámi clothing (gákti) and telling stories from our personal backgrounds (Figure 2). The first author also held a practical outdoor session in which the students planned a local, sustainable Sámi meal cooked on a campfire. In this second cycle, we wanted to elicit more in-depth perspectives from the students and conducted a group interview with three students upon the conclusion of the cycle.

In 2024, we aimed to further improve our teaching based on student feedback and our own collaborative reflections (Figure 2). This time, we distributed the sessions throughout the semester (weeks 2–15) and further clarified the intended aims and content knowledge to the students. Although there were only nine students that year, we wished to provide a new round of teaching to obtain more data and improve our teaching through a new action cycle.

2.3. Data

Our data consisted of responses to online (semi-quantitative) surveys, group interviews with students, and our own teaching notes (related to planning, execution, observation and evaluation, and reflection and replanning). The material was used to carry out the action-based research process (Figure 2).

2.3.1. Semi-Quantitative Survey

The online survey (https://nettskjema.no) was anonymous and was based on a questionnaire with items rated on a Likert scale and open-ended questions aimed at investigating how the students perceived the teaching interventions (Supplementary Materials S1). We used the item ratings, which indicated the level of agreement with various statements, to quantify attitudes, opinions, and perceptions []. This provided us with quality control and comparable results for each cycle. The open-ended questions aimed to give depth and nuances to the students’ evaluations of the teaching. We asked them to elaborate on what they perceived as challenging about the teaching and what provided learning benefits.

2.3.2. Group Interviews

We conducted two focus group interviews with three participants in each group shortly after the course examinations in 2023 and 2024 (Supplementary Materials S2). The inclusion criteria were that the interviewees had been present in all teaching sessions, had participated actively, and were from different places in Norway. They volunteered by showing interest in the classroom. We jointly conducted the interviews, which lasted 35 (2023) and 45 (2024) minutes, on Zoom and recorded them. We then transcribed them and gave the participants pseudonyms before the analysis.

2.3.3. Teaching Notes

The action-based research cycles included notes on planning (teaching plans), execution (teacher log), evaluation and reflection in the form of informal dialogues and joint written reflections. Each cycle resulted in changes to the teaching interventions (Figure 2).

2.4. Data Analysis

To ensure comparability between the different datasets, we expressed the questionnaire item ratings as percentages for each year. We inductively analyzed the open-ended questions using qualitative content analysis []. First, we both read through the answers and made impression notes separately. We then met to compare notes and agree on codes of patterns emerging from the answers (Table 1). We achieved inter-coder agreement by deductively recoding the data together to determine how to categorize, quantify, and interpret them.

Table 1.

Example of how we coded “active learning” in the survey’s open-ended answers.

To analyze the group interviews, we read the transcripts separately with the research questions in mind to collect feedback on our teaching interventions. When comparing notes, we agreed on the main findings that represented the interviewees’ opinions, which provided us with directions for new cycles. In Section 3, we provide representative quotations that confirm or expand the survey findings. We used ChatGPT [] to translate the quotations and checked the translations ourselves.

3. Results

In this section, we present the changes to the interventions through action research based on the students’ evaluations, which provided us with directions for developing our teaching.

3.1. Changes in the Teaching Interventions

The results presented herein were obtained after three cycles of teaching interventions (2022–2024) based on the online surveys (see Section 3.2 and Section 3.3) and two rounds of interviews (see Section 3.4). The adjustments made to replan the teaching cycles involved improving structural and pedagogical aspects (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of changes to our teaching interventions in accordance with Sámi pedagogical principles in line with Keskitalo and Määttä [], Balto [], and our aims.

From having a Sámi theme emphasized during the period around Sámi National Day (2022), we moved to gradually distributing it to the entire semester and conducting the practical work on Sámi food culture outdoors (2023–2024). Due to the coincident increased attention to Sámi issues in the media and society, celebrating Sámi National Day and focusing on reindeer meat as Sámi food culture served as starting points. However, we came to realize that this could reproduce the exotification of the Sámi and was not in line with the diverse and cyclic time frame of Sámi pedagogy []. Another important change was that we moved from individual single-discipline teaching to interdisciplinary co-teaching. These changes and the choice of teaching jointly wearing traditional Sámi clothing (2023–2024) were based on our own reflections rather than on the students’ evaluations.

The pedagogical part of the teaching was characterized by an emphasis on active learning, with the teachers acting as facilitators and supporters. The students collaborated on several tasks, and in the last year, they presented their findings from the LBG session to each other after two months to recall their self-selected topics for collaborative learning.

A major change in each year’s teaching content was an emphasis on the relationship with ancestors, ancestral lands, and values in Sámi culture related to sustainable livelihoods. For instance, we taught genealogy and Sámi food culture (learning objectives; see Table 2) separately in the two first cycles but braided them together in the last cycle. Throughout the cycles, we became more synchronized and familiar with our joint teaching content and intended focus on Sámi diversity and sustainability.

3.2. Survey

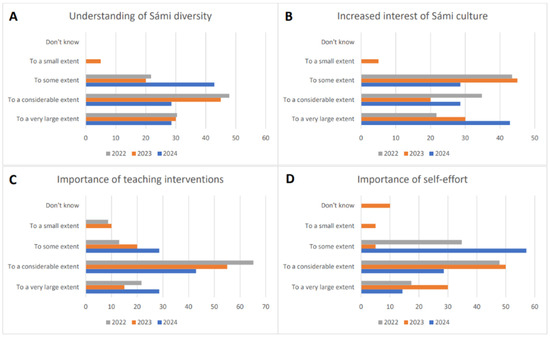

We conducted the online surveys shortly after the last session each year. Four quantitative questions provided us with an overall impression of the students’ self-evaluated understanding of Sámi diversity (Figure 3A), interest in Sámi culture (Figure 3B), and the importance of the teaching interventions (Figure 3C) and self-effort (Figure 3D) after the sessions.

Figure 3.

Students’ responses to questionnaire items (y-axis) rated on a five-point Likert scale indicating their self-reported degree of (A) increased understanding of Sámi diversity, (B) increased interest in Sámi culture, (C) the importance of the teaching interventions, and (D) the importance of self-effort. The results (x-axis) are shown as percentages of students (2022: n = 23; 2023: n = 20; 2024: n = 7). (A,B) shows the students’ evaluations of the teaching content, while (C,D) provides information about the teaching methods.

A comparison of the survey answers between the three years revealed that most students perceived an increased understanding of Sámi diversity (“to a considerable extent” or “to a very large extent”; Figure 3A). The results were very similar in 2022 and 2023, when there were 23 and 20 participants, respectively). Due to the few participants in 2024 (only 7), it was not possible to compare the results of that year with those of the previous years. However, we chose to include the 2024 results to repeat the round of teaching one more time.

To the question of whether the interventions made them more interested in Sámi culture, most students answered, “To some extent” (Figure 3B). Although the answers varied between the three years, we observed a pattern of progressively greater interest in Sámi culture from 2022 to 2024.

Most of the students answered that the teaching interventions were important for their learning “to a considerable extent”. The answers were largely consistent in all three years, with 65% (2022), 55% (2023), and 43% (2024), respectively (Figure 3C).

The answers regarding the importance of self-effort for learning (Figure 3D) varied considerably, but “to a considerable extent” was the most common answer. In 2023, a few students answered, “I don’t know” and “To a small extent”. This may reflect the degree of support provided to the students each year in the LBG session, which was intended to make the students independent and self-reliant (iešbirgejeddji).

Overall, our teaching affected the students’ self-perceived understanding of and interest in Sámi culture to a considerable or a large extent in all years. Our teaching methods significantly impacted their learning and self-effort.

3.3. Answers to the Open-Ended Questions in the Survey

To obtain more information from the students, the online survey included two mandatory open-ended questions about what they perceived as positive/beneficial/relevant (Table 3) or negative/challenging/irrelevant (Table 4) about the teaching. The students’ answers are summarized below.

Table 3.

Summary of what was perceived as positive/beneficial/relevant about the teaching interventions according to the answers to the open-ended questions in the survey.

Table 4.

Summary of what was perceived as negative or challenging about the teaching interventions according to the answers to the open-ended questions in the survey.

As shown in Table 3, almost all students (49 of 50) deemed the teaching positive or beneficial for their perceived learning, especially the LBG session (25 of 50), which was most frequently mentioned in the first cycle (2022). Generally, the students valued the variation in teaching methods (19 of 50) and group work (18 of 50) the most. Some students described the teaching methods as “good” (11 of 50), and some considered them to have “good balance” (10 of 50). Many students also noted their own contributions (35 of 50), particularly active learning (26 of 50). Many also mentioned the importance of self-effort, the obligation to perform (presenting their LBG findings), and contribution to each other’s learning, especially in the first year (2022). The “practical work” was mentioned most frequently in 2024 (5 of 7). Some students also noted the value of transferring the teaching to their work in kindergarten (10 of 50)

The second open-ended question was, “What do you think was challenging or was of little learning benefit in the sessions about Sámi culture?” The responses are summarized in Table 4.

A total of 29 out of 50 students answered that they perceived some sort of challenge. Interestingly, 16 of 50 students answered, “Nothing” or “It was good”. This indicates that one-third of the students were pleased with the teaching. Five of fifty answered, “I don’t know” or added a dot (.) in the answer field, which we interpreted as “no answer”. The students also elaborated on what they found challenging, with the most prevalent answers coded as follows (Table 4): “difficult to find information” (7 of 50 students), “long/uninteresting lectures” (6 of 50 students), and “too little or too much time” (6 of 50 students).

In summary, the open-ended feedback was positive overall, especially regarding active and collaborative learning. The students valued the variation and balance between different teaching methods, especially the practical and student-active work, which demanded self-effort.

3.4. Interview Data

The aim of the group interviews was to give depth and nuances to the answers in the survey and to help us gain a deeper understanding of what we needed to improve in our teaching. In the following subsections, we summarize what the students perceived as “good” and “less than good” about our teaching approaches and provide quotations as examples.

3.4.1. What Was Perceived as “Good”

The interviewees in both groups stated that our teaching provided them with concrete examples of how they could approach Sámi culture in kindergarten.

It’s nice to have some concrete examples of how to work on Sámi culture in kindergarten, […] in terms of culture and food culture.(Kim, 2023)

I feel that what I have learned is more about how I can better connect this knowledge to kindergarten.(Benny, 2024)

Both groups also mentioned the LBG session as a good teaching approach.

I liked learning by googling because there were quite a lot of different elements. I learned from that.(Robin, 2023)

That teaching session we had where we were divided into groups and had different themes related to Sámi culture. It was very, very useful. […] And then, when we shared it all together afterward, you suddenly gained a very broad knowledge of Sámi culture.(Isa, 2024)

The students also mentioned the practical outdoor work related to food resources.

It was quite nice to be allowed to go out and try […] outdoors with [first author], being allowed to see that it’s not so difficult to make Sámi food.(Alex, 2023)

I’ve always thought that simple [actions], like harvesting, were done. I never considered that there might be much more about Sámi. […] It made me aware of Sámi [culture] as a much broader food culture than I had previously thought.(Luca, 2024)

The interviewees perceived the Introduction to Sámi Land Areas and Genealogy session differently.

I didn’t find [the second author’s] teaching about the place and your Sámi ancestry to necessarily be super relevant to Sámi issues—especially if you come from places where there might not be a strong Sámi affiliation to begin with.(Kim, 2023)

It was fun to see the different families, and I found out that I was also a Sea [coastal] Sámi.(Robin, 2023)

Where the family comes from. I find this quite exciting as an introduction. What have people actually lived off? Also, the self-sufficiency that you should harvest and take what you find, but you should not harvest in excess.(Isa, 2024)

The relevance of Sámi culture to sustainability was noted by both groups but was more articulated by the 2024 group.

I experienced that [Sámi culture] was well connected to sustainability […] because they are related, and you can draw some parallels. […] Nice connection.(Kim, 2023)

I have always known that Sámi culture is very resourceful, that they tend to use everything they have, and that nothing is wasted. I haven’t strongly linked it to sustainability before.(Luca, 2024)

Sustainability. Harvesting. I really had no idea about harvesting and such before. […] Now, I can better understand why we do it.(Benny, 2024)

We were pleased to see that the students in the last cycle finally recognized the strong connection between Sámi culture and sustainability, especially in relation to genealogy and how to use local natural resources.

The quotes provided above show that the teaching content was relevant and could be transferred to teaching in kindergarten. Sustainability was additionally acknowledged as a Sámi cultural principle. The LBG sessions and the practical work related to outdoor cooking were perceived as good teaching methods.

3.4.2. What Was Perceived as “Less than Good”

The interviewees in 2023 had divergent experiences with the Genealogy session (see Section 3.4.1). Two of them (Kim and Alex) did not see it as relevant, whereas one (Robin) valued it highly. We learned that this student was of Sámi origin, whereas the other two were not. This feedback made us aware that we needed to focus more generally on the importance of the locality of family traditions for one’s livelihood and on the fact that Sámi culture grows from relationships with the land, the surroundings, and one’s ancestors. We needed to adjust our teaching to make it relevant to the place and land for all students, regardless of their ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

The 2024 group interview revealed that the Genealogy session worked as intended for all interviewed students. The 2024 interviewees had nothing more to add about what was less good except that they wanted us to use more Sámi terms in our teaching.

4. Discussion

By developing our teaching through action-based research, we transformed our traditional disciplinary teaching into more coherent and interdisciplinary teaching about the diversity of Sámi culture. This holistic teaching approach aligned with core features of Sámi culture and pedagogy [,] and helped the students actively engage in acquiring knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes related to Sámi culture. In this ECTE course, we aimed to nannet (strengthen and acknowledge) Sámi culture and to deliver teaching that holistically contributed to the students’ learning about Sámi diversity.

Student-driven practical and explorative work, such as LBG and preparing Sámi foods outdoors, were crucial elements that contributed to the students’ perceived learning (see Table 3 and Section 3.4). The teaching required independent student-active work and collaboration in groups, while we, as teachers, played a directive, advisory, and supportive role, which is a hallmark of Sámi pedagogy []. The students mentioned these as important features of the teaching methods and as essential for their learning outcomes (see Table 3 and Section 3.4). Moreover, the practical tasks counterbalanced the theoretical parts of the sessions.

The perceived challenges related to our teaching (see Table 4) helped us identify areas for improvement or change. For example, the responses in 2023 indicated that some students did not see the purpose of genealogy research. To address this, we directed our teaching toward the importance of family relations and ancestors’ relationships with nature. Moreover, we highlighted the significance of landscapes and the sustainable use of natural resources to emphasize Sámi cultural principles. Based on this, we also worked on clarifying the learning goals, helping students see the connection between Sámi culture, relationships with nature, and sustainability—topics that were revisited throughout the 2024 cycle.

The responses to the quantitative part of the survey (see Figure 3) suggest that the students’ self-perceived understanding of the diversity of Sámi culture was similar in all years despite our efforts to improve our teaching. However, the students’ interest in Sámi culture increased somewhat each year, which may reflect our improvements. Nevertheless, the perceived importance of teaching and self-effort varied between the three years. These results confirm the importance of qualitative data for providing depth and directions for development in action research.

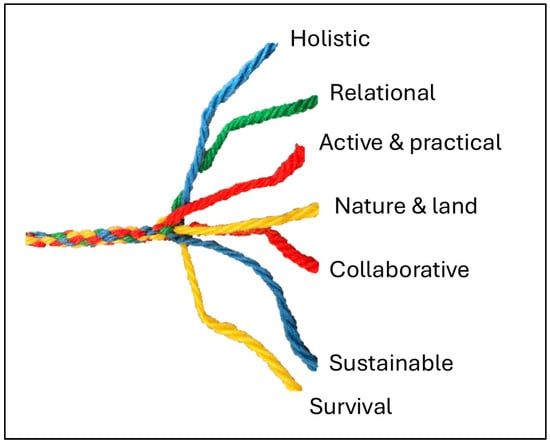

Overall, our teaching developed into a more holistic approach to learning by braiding principles from Sámi child rearing [] and Sámi pedagogy [] with our traditional, theoretical lecture-based pedagogy (see Table 2 and Figure 4). Braiding knowledge systems together is based on relational processes through time, places, and generations [], repeatedly reflecting on how teaching is approached and conducted [] and taking students’ feedback into consideration. This dynamic, relational, and continuous process of braiding knowledge and teaching methods together must maintain the authenticity of Sámi culture and pedagogical practice []. We incorporated Sámi principles of living with nature in harmony through a connection to ancestors and places (see Figure 4). Furthermore, we cooked local foods on a campfire with limited equipment. The students experienced how to make food with simple means, connecting the past to the present and land to people, thereby exemplifying a holistic perspective on living and practicing sustainability [,].

Figure 4.

Overall changes that aimed to braid and strengthen (nannet) Sámi diversity and pedagogy in our teaching interventions.

The feedback from the last cycle indicates that the students understood the deep connection between Sámi culture and sustainability. They also valued the variation and balance between different teaching methods, especially the practical and student-active work, which required self-effort—a practice inspired by Sámi pedagogy. These practical, active, and holistic teaching methods can easily be applied to daily life in kindergarten, not just on Sámi National Day but throughout the year.

The holistic and flexible ways of practicing Sámi pedagogy have even greater potential. For example, instead of PowerPoint presentations, we could have employed more storytelling, invited traditional knowledge bearers to provide an authentic exchange of cultural knowledge between generations (searvelatnja) [], and made greater use of authentic contexts, such as outdoor places, goathi (Sámi turf huts), and campfires. The interviewees in the last cycle suggested that we incorporate more Sámi terms into our teaching. This suggests that we need to learn Northern Sámi and delve more deeply into Sámi literature.

Limitations

Certain limitations of our study may have influenced our interpretations and conclusions. Most importantly, the students’ answers may have, to some degree, been affected by their desire to please us as their teachers. This may be particularly true for the 2022 survey, which the students knew was part of the second author’s pedagogical development project that was a prerequisite for teaching in higher education (see Section 2.2). This “desire to please” may also have influenced who participated in the group interviews: The volunteers were likely to be students who liked us as teachers.

The risk of bias in interpreting data is always present, especially in action research, as the researcher is directly involved in the field under study. However, we mainly used our data to evaluate and adjust our teaching rather than to draw conclusions. On the same note, our personal histories as coastal Sámi, our perspectives, and our experiences may have influenced the entire research process, from formulating the research questions to interpreting the data.

Another error that may have influenced the students’ responses is that our course was conducted simultaneously with another course covering different aspects of Sámi culture. This overlap may have led students to confuse the Sámi teaching contents and methods in the two ECTE courses when responding to the survey.

Finally, this study may also have certain theoretical limitations. Few scholars have explored or conceptualized Sámi pedagogy or braided Indigenous methodologies into education in Sápmi—at least in a language that we can read, such as Norwegian, Swedish, or English (we cannot read any Sámi languages).

5. Conclusions and Implications

The contribution of our teaching to students’ knowledge of and interest in Sámi diversity was mostly related to how we, as teachers, approached Sámi ways of being, knowing, and doing. The students pointed to the practical, collaborative, and student-active assignments (LBG and preparing food outdoors) as most relevant to their learning outcomes, whereas they deemed genealogy somewhat less relevant. The students’ feedback and our joint reflections after each teaching cycle guided us in how to nannet (strengthen or acknowledge) and braid our teaching with Sámi holistic values and the relationship of the Sámi with their ancestors, family lands, and the sustainability of natural resources, which is important for Sámi people's livelihood and cultural traditions.

Our study has implications for teachers aiming to integrate Sámi or other Indigenous pedagogical principles into their teaching for majority populations. Braiding as a metaphor connects time, space, generations and traditions and honors every thread that is woven. In this work, relationships are crucial. Engaging with culturally sensitive topics, such as Indigenous issues, should begin with easily conceivable connections. Reflecting on how we, as researchers, teachers, and students, relate to the Sámi culture through our ancestors and land in our current environment is an essential starting point. Despite the wealth of information that can be found online today, including information on Indigenous cultures, direct experiences such as cooking over a campfire remain invaluable. Engaging with traditional knowledge and skills and sustainable living practices can develop competencies for a sustainable future []. Particularly, the dimension of cultural sustainability is important, as it aims to honor and revitalize Indigenous cultures with pride and respect. Braiding Sámi knowledge into ECTE may extend beyond this research and can be perpetuated by our students as future teachers in kindergarten and beyond.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci14111212/s1, Supplementary Materials S1: Survey questions S1, Supplementary Materials S2: Interview Guide S2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H. and V.B.; methodology, G.H. and V.B.; validation, G.H. and V.B.; formal analysis, G.H. and V.B.; investigation, G.H. and V.B.; resources, G.H.; data curation, G.H.; writing—original draft preparation, G.H. and V.B.; writing—review and editing, G.H. and V.B.; visualization, V.B.; project administration, G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research with protocol code 738556 and date of approval 10 January 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ECTE students for their willingness to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Norway. Rapport til Stortinget fra Sannhets- og Forsoningskommisjonen. In Report to the Storting from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; Høybråten, D., Ed.; The Norwegian Government: Oslo, Norway, 2023; Available online: https://www.stortinget.no/no/Stortinget-og-demokratiet/Organene/sannhets--og-forsoningskommisjonen/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Kunnskapsdepartementet. Regulation on the Framework Plan for Early Childhood Teacher Education; FOR-2012-06-04-475; Kunnskapsdepartementet: Oslo, Norway, 2012; Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2012-06-04-475 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Ministry of Education and Research. Framework Plan for Kindergartens—Content and Tasks; Kunnskapsdepartementet: Oslo, Norway, 2017; Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SFE/forskrift/2017-04-24-487 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Olsen, T.A.; Sollid, H.; Johansen, Å.M. Knowledge of Sami Matters as an Integrated Part of Teacher Education Programs. Acta Didact. Nor. 2017, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homme, A.; Danielsen, H.; Ludvigsen, K. Implementation of the Framework Plan for Kindergartens: Interim Report from the Project Evaluating the Implementation of the Framework Plan for Kindergartens. 2021. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2736721 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Danielsen, H.; Olsen, T.; Eide, H.M.K. Performing Nationalism—Sámi Culture and Diversity in Early Education in Norway. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2023, 22, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, R. From Norwegianization to Coastal Sami Uprising. In Indigenous Peoples: Resource Management and Global Rights; Jentoft, S., Minde, H., Nilsen, R., Eds.; Eburon: Tongeren, Belgium, 2003; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Keskitalo, P.; Määttä, K. Sámi Pedagogihka Iešvuođat = Saamelaispedagogiikan Perusteet = The Basics of Sámi Pedagogy = Grunderna I Samisk Pedagogik = Osnovy Saamskoj Pedagogiki; Lapin Yliopistokustannus: Rovaniemi, Finland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vangsnes, Ø.A.; Nygaard, V.; Kårtveit, B.; Johansen, K.; Sønstebø, A. Sámi Numbers Tell No.14; Sami Allaskuvla: Kautokeino, Norway, 2021; Available online: https://sametinget.no/grunnopplaring/nyttige-ressurser/samiske-tall-forteller/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- The Norwegian Government. ILO Convention 169—Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention; 1990; Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/urfolk-og-minoriteter/samepolitikk/midtspalte/ilokonvensjon-nr-169-om-urbefolkninger-o/id451312/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Andresen, A.; Evjen, B.; Ryymin, T. History of the Sámi from 1751 to 2010; Cappelen Damm Akademisk: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Todal, J. Minorities with a Minority: Language and the School in the Sami Areas of Norway. Lang. Cult. Curric. 1998, 11, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joks, S.; Østmo, L.; Law, J. Verbing meahcci: Living Sámi Lands. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 68, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttorm, G. Traditions and Traditional Knowledge in Sámi Culture. In Being Indigenous; Greymorning, N., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, S.; Joks, S.; Andersen, S. Lubmen—ja mannenpráksisat Porsáŋggus—Mo mearrasámi guovllu olbmot dádjadit iežaset birrasiin [Cloudberry and egg gathering practices in Porsanger—how Sámi people find their way in their own environment]. Sámi dieđalaš áigečála 2022, 7–30. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Solveig-Joks/publication/370021020_Lubmen-_ja_mannenpraksisat_Porsanggus_-_mo_mearrasami_guovllu_olbmot_dadjadit_iez-set_birrasiin/links/643fe82e39aa471a524c97e3/Lubmen-ja-mannenpraksisat-Porsanggus-mo-mearrasami-guovllu-olbmot-dadjadit-iezaset-birrasiin.pdf. (accessed on 20 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Heim, G. Sámi food culture. In To Make—Sámi Topics in School and Education; Solheim, S.S., Figenschou, G., Pedersen, H.C., Eds.; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2023; pp. 170–185. [Google Scholar]

- Rybråten, S.; Aira, H.; Andersen, S.; Joks, S.; Nilsen, S. Foraging Practices in Sami Coastal Areas—Relationships, Values, and Sustainability. Tidsskr. Samfunnsforskning 2024, 65, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.K.; Siragusa, L.; Guttorm, H. Introduction: Toward More Inclusive Definitions of Sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 43, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A. About the Sea-Sámiand Other Publications; Bjørklund, I., Gaski, H., Eds.; ČalliidLágádus: Kautokeino, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Valkonen, J.; Valkonen, S. Contesting the Nature Relations of Sámi Culture. Acta Boreal. 2014, 31, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervaniemi, S.; Magga, P. Belonging to Sápmi—Sámi Conceptions of Home and Home Region. In Knowing from the Indigenous North; Eriksen, T.H., Valkonen, S., Valkonen, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Balto, A.M.; Johansson, G. The Process of Vitalizing and Revitalizing Culture-Based Pedagogy in Sámi Schools in Sweden. Int. J. About Parents Educ. 2023, 9, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocq, C. Traditionalisation for Revitalisation: Tradition as a Concept and Practice in Contemporary Sámi Contexts. Folk. Electron. J. Folk. 2014, 57, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtola, V.-P. Contested Sámi Histories in Finland. In Sámi Research in Transition; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rusk, M. Transforming Education and Educators: Validating Indigenous Knowledge in Principle and Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G.A. Envisioning Indigenous Education: Applying Insights from Indigenous Views of Teaching and Learning. In Handbook of Indigenous Education; McKinley, E.A., Smith, L.T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, C.; Pereira, F.; Amorim, J.P. The integration of indigenous knowledge in school: A systematic review. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2023, 54, 1210–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, R.C.; Berkes, F. Local Understandings of the Land: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Indigenous Knowledge. In Nature Across Cultures: Views of Nature and the Environment in Non-Western Cultures; Selin, H., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 2003; pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Guttorm, G. Árbediehtu (Sami Traditional Knowledge)—As a Concept and in Practice. In Working with Traditional Knowledge: Communities, Institutions, Information Systems, Law and Ethics; Porsanger, J., Guttorm, G., Eds.; Sámi University College: Kautokeino, Norway, 2011; pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Balto, A.M. Sami Upbringing—Tradition. Renewal. Vitalization; ČálliidLágádus: Kautokeino, Norway, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bjøru, A.-M.; Solbakken, A.R. Birgejupmi—Life Skills, the Sámi Approach to Inclusion and Adapted Education. Morning Watch. Educ. Soc. Chang. 2021, 47, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Laiti, M. Searvelatnja—A Cummunality Principle in Sami Early Childhood Education (SECE). In Girjjohallat Girjáivuođa—Embracing Diversity: Sami Education Theory, Practice and Research; Keskitalo, P., Olsen, T., Drugge, A.-L., Rahko-Ravantti, R., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, in press.

- Sara, M.N. Traditional Sámi Knowledge and Skills in Primary School. In Sámi School Curriculum and Practices; Hirvonen, V., Ed.; ČálliidLágádus: Karasjok, Norway, 2003; pp. 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Demssie, Y.N.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Wesselink, R.; Mulder, M. Combining Indigenous Knowledge and Modern Education to Foster Sustainability Competencies: Towards a Set of Learning Design Principles. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druker-Ibáñez, S.; Cáceres-Jensen, L. Integration of indigenous and local knowledge into sustainability education: A systematic literature review. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidny, R.; Sjöström, J.; Eilks, I. A Multi-Perspective Reflection on How Indigenous Knowledge and Related Ideas Can Improve Science Education for Sustainability. Sci. Educ. 2020, 29, 145–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figenschou, G. How on earth do I dare to work with Sami themes in education. In To Make—Sámi Topics in School and Eduation; Solheim, S.S., Figenschou, G., Pedersen, H.C., Eds.; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2023; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, K.G.; Goldschmidth-Gjerløv, B.; Jore, M.K. Controversial, Emotional and Sensitive Topics in School; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Somby, H.M.; Olsen, T.A. Inclusion as Indigenisation? Sámi Perspectives in Teacher Education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote-Meek, S.; Moeke-Pickering, T. Decolonizing and Indigenizing Education in Canada; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, T.A. Indigenizing Education in Sápmi/Norway: Rights, Interface and the Pedagogies of Discomfort and Hope. In Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, T.A.; Sollid, H. Introducing Indigenising Education and Citizenship. In Indigenising Education and Citizenship: Perspectives on Policies and Practices from Sápmi and Beyond; Scandinavian University Press: Oslo, Norway, 2022; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, B.-O.; Olsen, T.A. Indigenous People and National Minorities in Schools and Teacher Training; Fagbokforlaget: Bergen, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, A.N.N. The Whitestream. Counterpoints 2017, 513, 3–26. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45136366 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Porsanger, J. An Essay about Indigenous Methodology. Nordlit 2004, 15, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimmy, E.; Andreotti, V.; Stein, S. Towards Braiding; Musagetes: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, R. Braiding Aweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants; Milkweed Editions: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, H.E.; Madden, B.; Higgins, M.; Ostertag, J. Braiding Designs for Decolonizing Research Methodologies: Theory, Practice, Ethics. Reconceptualizing Educ. Res. Methodol. 2018, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finbog, L.-R. It Speaks to You-Making Kin of People, Doudji and Stories in Sàmi Museums; DIO Press: Lewes, DE, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, K.G.; Aamaas, Å.; Bjerkenes, A.-L. To Listen to—And to Engage in Story Telling. 2022. Available online: https://www.dembra.no/no/fagtekster-og-publikasjoner/publikasjoner/a-lytte-til-og-a-engasjere-seg-i-fortellinger (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Gibbs, P.; Cartney, P.; Wilkinson, K.; Parkinson, J.; Cunningham, S.; James-Reynolds, C.; Zoubir, T.; Brown, V.; Barter, P.; Sumner, P.; et al. Literature review on the use of action research in higher education. Educ. Action Res. 2017, 25, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noffke, S.E.; Somekh, B. (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Educational Action Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.S.; Porath, S.; Thiele, J.; Jobe, M. Action Research; New Prairie Press: Manhattan, KS, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Altrichter, H.; Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Zuber-Skerritt, O. The Concept of Action Research. Learn. Organ. 2002, 9, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Committee for Research Ethics. Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities. Available online: https://www.forskningsetikk.no/en/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Universitets—og Høgskolerådet. National Guidelines for Basic Competences in Higher Education Teaching. Available online: https://www.uhr.no/temasider/karrierepolitikk-og-merittering/nasjonale-veiledende-retningslinjer-for-uh-pedagogisk-basiskompetanse/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Nemoto, T.; Beglar, D. Developing Likert-Scale Questionnaires. In JALT 2013 Conference Proceedings; Tokyo, Japan, 2014; Available online: https://jalt-publications.org/sites/default/files/pdf-article/jalt2013_001.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. ChatGPT Model 3.5. 2024. Available online: https://chat.uit.no/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).