Abstract

Latine parent educational engagement literature has established that parents employ rich cultural resources across their environments to support the P-20 attainment of their children. In this qualitative case study, we combine the funds of knowledge framework with constructs of ecological systems theory to add a clearer l perspective of how and with whom Latine parents and communities mobilize their funds of knowledge, highlighting their advocacy and agency. Findings identify instances in which Latine parents navigate different social interactions and spaces at various system levels and demonstrate the ways in which college outreach programs can have positive influences beyond the immediate systems of the home and school.

1. Mobilization of Funds of Knowledge in Ecological Environments: Latine Parent Engagement in a College Outreach Program

The critical role parents play in the educational development and achievement of Latine students is well established in extant literature, as is the crucial need for schools to establish meaningful relationships with families of color [1,2,3,4,5,6]. However, many Latine parents continue to perceive and experience their children’s educational settings as spaces of marginalization and alienation as opposed to empowerment and connection [5,7,8]. Parental engagement literature has problematized school-centric models of involvement that approach Latine parents as problematic and in need of remediation [9,10].

Scholars have examined how traditional involvement practices limit parents to discrete activities and compliance behaviors in which they fulfill passive roles bound by the dominant expectations and parameters of educators [6,11,12]. These racialized deficit notions act as barriers for Latine parents that influence how and with whom they interact within the ecological environment in support of their children’s education. To address these concerns, decades of research have called for parental engagement models that offer meaningful opportunities and spaces for families of color, and specifically Latine families, to enact new rules of engagement that disrupt dominant discourses and that center their knowledge and community connections [7,13,14,15]. Such models support families of color to move beyond simple compliance or resistance and to nurture an individual and collective agency in education and across various systems [9,12,16].

In some cases, Latine parents create their own spaces for school engagement spanning pre-school through graduate education, or P20. For instance, Jasis [13] shared how Latine immigrant families involved in migrant education, programs, and school/community action groups demonstrated commitment, ingenuity, strength, and support. Their engagement called for inclusive and respectful partnerships between families and schools that illustrate their rich cultural wisdom [13].

2. Current Study

The purpose of this paper is to expand current understanding of Latine parent engagement and provide a framework through which to make sense of how funds of knowledge, combined with knowledge gained from a college outreach initiative, are mobilized across the context of different ecological systems to support children’s postsecondary educational attainment outcomes. A significant contribution of this paper is illustrating how Latine parents share this educational knowledge with other families and in various ecological contexts, highlighting their rich cultural agency, advocacy, and resiliency within these spaces. Specifically, this paper illustrates instances in which Latine families mobilize their funds of knowledge as a means of not only navigating different ecological systems and developing connections in support of their children’s education, but also extending educational opportunities for their communities.

We do so by complementing the funds of knowledge (FoK) framework with Bronfenbrenner’s [17,18] ecological systems theory (EST) and Neal and Neal’s [19] reconceptualization of EST as a networked rather than nested model. The College Knowledge Academy (CKA) (The College Knowledge Academy (CKA) is a pseudonym) is a 12-week parent college outreach program that provides the context from which Latine families first came together to learn about college preparation. We illustrate how families’ social interactions in the college outreach program setting can influence the interactions and relationships that occur across a network of ecological systems that surround Latine parents and their children. The following research question guides this paper: When considering the different ecological systems in which College Knowledge Academy families interact, how are funds of knowledge mobilized and shared among the different ecological systems in support of children’s postsecondary educational pursuits?

3. Review of Relevant Literature

Latine families and their home environments are rich sources of cultural and historical knowledge that contribute to opportunities for children to learn and develop educational aspirations across elementary, secondary, and postsecondary pathways [4,20,21]. Grosso Richins et al. [22] suggest that when Latine parent and family engagement is understood through an asset-based lens and recognizes their forms of community cultural wealth [23], positive contributions to school, home, and community can be cultivated. Specifically, their phenomenological study with bilingual education teachers and seven Latine parents found that parents cultivated environments that encouraged high academic expectations and supported their children to develop strong educational aspirations. Latine parents also developed collaborative relationships with their children’s teachers, prioritized their home and heritage language, and drew on family resources to support their children’s education [22]. The bilingual education teachers in the study also employed strategies to “enhance the participation of Latine parents at home and in the schools that reflected the ways these parents access their social, cultural, and linguistic capital” (p. 387). Their findings add to a long-established body of literature that highlights the ways in which Latine families’ agency and values around education and educación contribute to high educational aspirations [4,24,25,26]. For instance, Espino’s [25] article focused on the interpretations and (re)tellings of Mexican–American parental/familial messages around education and the formation of educational aspirations. Her findings dispelled deficit discourse around Mexican–American parent engagement. Like Gross Richins et al. [22], Espino’s [25] important research focused on families’ cultural agency, cultural integrity, and accumulation of capital that provided a foundation for Mexican–American students to navigate education.

Rich cultural advocacy and agency is particularly evident in Quiñones and Kiyama’s [26] article, where they focus specifically on the role of Latine fathers. Their research demonstrates how Latinx fathers pushed back against multiple systems (educational, immigration, language). They draw on the idea of moving contra la corriente or going against the current as they work in collaboration with community members and other families. Their high aspirations for their children were understood through their own experiences with navigating barriers within systems that had worked to push them away from educational opportunities [26].

Examples of asset-based and parent-led engagement practices, specific to Latine families, are often exhibited in and cultivated through school-based community action groups, as well as college outreach and access programs [13,27,28,29,30,31]. A growing number of partnerships between K-12 schools and universities have also been developed to provide historically underrepresented families and students with enhanced preparation for postsecondary education [1,28,32].

For instance, Durán et al. [33] focused on understanding and examined issues of critical awareness of school and social issues, cultural knowledge and cultural worlds, and educational policies with Latinx immigrant parents who participated in Padres Líderes, a parent–school engagement program in California. Drawing on asset-based frameworks (inclusive of funds of knowledge), they found that cultural wisdom informed, shared through cultural practices like dichos, refranes, and pláticas, and strengthened their engagement practices, particularly when advocating for school policy changes. Likewise, Mariscal’s [34] dissertation research highlighted how Latine parents came together to develop and implement college preparation workshops for other families in their local schools. In many situations, the engagement demonstrated by Latine families was not formalized initiatives coordinated through the schools but organized by the families themselves.

Many of these inclusive partnerships and outreach programs intentionally engage parents with the goal of fostering different forms of capital throughout the families [21,27,35] and providing students and/or their families with the “college knowledge” needed to successfully access and transition into higher education [36]. Families are encouraged to draw upon their own foundations and funds of knowledge, understood as the rich cultural histories, knowledges, and survival strategies utilized and shared within families [37] and home languages [28], as they incorporate educational strategies that build upon the rich social relations and networks and cultural resources of their communities [4,5]. In turn, college outreach programs have increasingly helped to mitigate structural barriers that traditionally limit, devalue, or ignore the educational aspirations and involvement of diverse families [35]. This is particularly evident in Gonzalez and Villalba’s [28] research, which indicates that when college-going knowledge is offered in familiar community spaces (i.e., schools and congregational settings) and delivered in the family’s home language (i.e., Spanish) by trusted community members, parents experience self-efficacy and “life changing” opportunities for themselves and their children. Latine parents encounter affirming, culturally rich, and supportive social interactions through which they develop their families’ educational goals and gain a greater sense of agency that influences their mobilization of funds of knowledge across various systems.

4. Guiding Frameworks

Two frameworks inform this study. First, we draw on funds of knowledge [20,37] specifically the evolution of the framework in which [38]) offers key characteristics around the recognition, transmission, conversion, and activation/mobilization of funds of knowledge. We complement funds of knowledge with Bronfenbrenner’s [17,18] ecological systems theory and organize the findings around each of the five system types. We pay particular attention to how cultural knowledge (e.g., funds of knowledge) is transmitted through social interactions in different environmental contexts, like home, communities, and schools, which illustrate the bridging of the two conceptual models. The strength of utilizing these frameworks together is that it offers a lens from which we can understand how funds of knowledge within the home intersect with the college knowledge and relationships gained from engagement in spaces like outreach programs to influence families’ patterns of interactions across their ecological environments. In tracing these patterns, we identify how cultural traits and knowledge are then transmitted, developed, and sustained through the interacting systems.

5. Funds of Knowledge

Funds of knowledge as a framework situates households’ social histories, methods of thinking and learning, and practical skills related to a community’s everyday life, especially labor and language, and attempts to derive instructional innovations and insights from such analysis [20]. Funds of knowledge accumulate within families and communities over time [37] and work from the assumption that communities have experiential, historical, and cultural knowledge of value to share [20]. Funds of knowledge “refer to the historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills essential for household or individual functioning and well-being” [37], (p. 133) that are cultivated and sustained through knowledge-sharing networks. These networks, often referred to as cluster households or cluster networks, provide space within the community for children to learn, play, and associate [39]. These relationships and networks can be found within the home (e.g., family member/child knowledge sharing), within cluster households or neighborhoods (e.g., acts of reciprocal knowledge sharing among neighbors or friends), and within broader communities (e.g., sharing of knowledge with co-workers), to name a few examples. Social relationships provide a motive and context for applying and acquiring knowledge when the content of the interactions is necessary for people to transfer that knowledge and other resources [38]. Thus, social interactions and networks are central to the framework as funds of knowledge are exchanged in addressing the demands of everyday life [40]. When mobilized, the power of these networks between families and systems becomes an asset in educational spaces [20]. Nearly fifteen years of research illustrate how the cultural knowledge embedded in the life experiences of underserved students and their families can inform a powerful foundation for classroom curriculum, college knowledge development, college outreach curriculum, and college transition [4,41]. For example, Kiyama [4] (has written extensively on the ways Latine and specifically Mexican–American families’ funds of knowledge influence the college-going paths of children. Kiyama’s [4] article expanded previous research on funds of knowledge by documenting Latine families’ funds of knowledge within their homes and the ways in which funds of knowledge influenced the formation of college-going ideologies, informed college-going processes, how families’ social networks contributed to educational funds of knowledge, and the ways in which academic symbols became part of families’ funds of knowledge used as a tool to explain and build college-going realities.

Rios-Aguilar, et al. [38] present four distinct mechanisms: (mis)recognition, transmission, conversion, and activation/mobilization of funds of knowledge and its relationship with forms of capital. Drawing from Anyon [42], Rios-Aguilar and colleagues [38] suggests that funds of knowledge can be transformed into agency and power when students have cultural tools available to create such transformation. Transmission then is necessary to examine in a wider range of educational and environmental contexts [38]. Within this framework, conversion is defined as “the process in which students and families convert their funds of knowledge into forms of capital” (p. 177). For example, a first-generation Latine family may be familiar with a college campus because they frequent it to attend football games. After attending a college outreach program, they learn about the importance of college tours when making college-choice decisions. The next time the family attends a football game, they show their children around campus and use a campus map to identify buildings. Thus, funds of knowledge within the home (e.g., a family ritual of attending campus football games), when activated with new information (learning about college tours), convert into a form of recognized capital (e.g., formal knowledge about a campus). Finally, activation/mobilization can be understood as the ways in which individuals utilize their investment in a given sociocultural situation to achieve their goals [38]. The processes of transmission and conversion, particularly within families’ cluster networks and social interactions in various environments, are particularly important to consider when connecting funds of knowledge with ecological systems theory. As noted above, transmission of knowledge within different environments becomes a central conceptual bridge between the two frameworks.

6. Ecological Systems Theory

Bronfenbrenner’s [17,18] ecological systems theory (EST) is a useful model to further frame and contextualize how families activate and mobilize their funds of knowledge. The EST conceptualizes an individual as directly and indirectly connected to interdependent and multilevel systems that can influence individual development. Bronfenbrenner [18] characterized the ecological environment as comprised of five systems: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. Each system arises from a setting where individuals engage in social interactions, and the system level is determined by the position of the focal individual relative to those interactions. In this paper, we utilize Neal and Neal’s [19] definitions of each system construct as presented in Table 1 to inform our analysis.

Table 1.

Definitions of Ecological System Constructs.

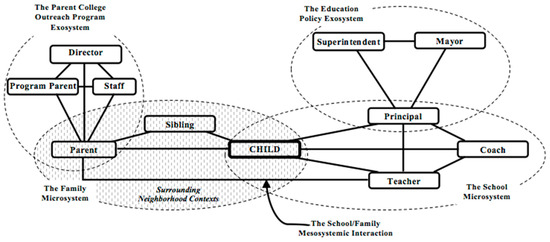

While Bronfenbrenner [17] described the ecological environment as “a set of nested structures, each inside the next like a set of Russian dolls” (p. 11), Neal and Neal [19] challenge this perspective. The authors argue it obscures the important role of social networks and the relationships that exist within and among systems. Neal and Neal [19] propose we re-conceptualize the ecological environment as networked with “overlapping structures, each directly or indirectly connected to the others by the direct and indirect social interactions of their participants” (p. 727). In doing so, the focus of the setting is inverted so that patterns of social interactions become primary to considerations of spatial factors. Similarly, the transmission and mobilization of funds of knowledge is largely predicated on the important role of social networks while also acknowledging spatial influences. Thus, while we draw on Bronfenbrenner’s [17] ecological systems theory, we employ it in the networked perspective of Neal and Neal [19].

A networked model offers the opportunity to trace the varying relationship forces that surround the developing child. Specifically, we can visualize how the child’s parents engaged in different system-constructed interactions and settings to support their child’s educational attainment. In drawing on these constructs of EST, we are able to bring a topological perspective to the mobilization of funds of knowledge in the ecological environment. To illustrate our application of EST, Figure 1 presents an adapted example of Neal and Neal’s [19] networked model, to which we added the additional exosystem interactions of a parent college outreach program setting. (For the purposes of this paper and its focus on parents, we simplify our example of how a college outreach program intersects with the family microsystem and indicate the parent as having the direct social relationship. However, we recognize the patterns of social interactions are context-specific and may differ for the child and the sibling in other scenarios). Figure 1 also includes a shaded reference (For discussion purposes, the shaded reference visually simplifies the representation of the myriad of neighborhood social interactions and contexts that families may encounter. However, we acknowledge that the additional system structures and ecological influences brought to bear on Latine families in real life from such neighborhood interactions are more complex) in the urban neighborhood contexts that Latine families within this study are embedded within and must physically and emotionally navigate as they move towards educational success for their children over time.

Figure 1.

Adapted from Neal and Neal [19], Example Illustrating a Networked Model of Ecological Systems with Addition of Parent College Outreach Program Exosystem and Surrounding Neighborhood Contexts.

While the macrosystem and chronosystem are not depicted in Figure 1, we briefly note the implications of these system influences to support our later findings and discussion. The macrosystem is associated with cultural, political, and social phenomena, which influence the patterns of social interactions within and across other systems [19]. For example, in Figure 1, the parent of the family microsystem may have a limited mesosystemic relationship with their child’s teacher that is influenced by experiences with discrimination in educational spaces. Lastly, the chronosystem acknowledges that the patterns of social interactions can remain stable or change over time. For example, as the parent in Figure 1 completes the college outreach program, the support and knowledge gleaned from the outreach program may also motivate the parent to strengthen their existing mesosystemic interaction with the child’s teacher or establish new connections with other parents in the community to share their college knowledge.

7. Methodology

This study represents a single-case study inclusive of embedded cases [43,44,45,46]. Our research paradigm is aligned with that of community-based research (CBR), which is defined as “a partnership of students, faculty, and community members who collaboratively engage in research with the purpose of solving a pressing community problem or effecting social change” [47] (p. 3). In this study, practitioner partners helped in the research design, data collection and analysis, and presentation of findings. The staff of CKA were involved in each stage of the research process, with one member of the staff serving as a co-researcher (e.g., approved through IRB). Kiyama (the PI on the project) met consistently with CKA staff to draft interview protocols, establish a recruitment plan, and conduct interviews. The CKA co-researcher was lead researcher for all Spanish-speaking interviews, lead author on a peer-reviewed journal article based on the project, and lead author on multiple local and national presentations. At various points throughout the project, Kiyama shared preliminary findings with the CKA staff and with local community members, including members of the school board within the district with which CKA partners. These community check-in meetings provided space for questions to be asked about the project, the emerging findings, concerns, and possibilities for action. The regular communication and project updates also served as checks to mitigate issues of power.

Our goal was to familiarize ourselves with how the College Knowledge Academy (CKA), a college outreach program for parents, utilized funds of knowledge as a programmatic framework and explore the continued development of funds of knowledge and college ideologies within Latine families. The CKA represents the bound case in this study, while the nature of the subunits allows us to give analytical attention to the 20 family clusters that make up the embedded cases. We have also included multiple points of data as suggested in case study literature [46]. We engaged in three phases of data collection in which multiple points of data were collected, as suggested by case study literature [46]. Phase I included individual interviews with program administrators; Phase II included interviews with families who participated in the initial years of the outreach program, inclusive of former student participants who were currently in the transition to college; and Phase III included the collection of program documents and artifacts. For the purpose of this paper, we focus our analysis on Phase II of the data collection—interviews with former parent, family, and student participants as they offer specific insight into family engagement within and across various systems.

8. The College Knowledge Academy

College Knowledge Academy (CKA) was developed in 2004 through a partnership between an early outreach office at a large public, land-grant institution and a local school district. The institution became a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) in 2018. Interestingly, many of the staff and faculty involved with the creation of CKA in 2004 were also instrumental in supporting the institution’s path towards becoming an HSI. The institution is located in a city with a population of approximately 1 million people across the metropolitan area. The neighborhoods, schools, and communities in which CKA families live and work are located approximately 15 min south of the university and about an hour north of the U.S./Mexico border. This smaller segment of the larger metropolitan area is zoned as its own city with approximately 6000 people and is bounded by two freeways and a railroad track.

The catalyst for CKA came from community need—local parents and families requested opportunities to learn about college-going beyond the one-stop college fairs. Therefore, the outreach program was developed for parents of elementary students ranging from kindergarten to sixth grade. The majority of the families that the program serves each year are Spanish-speaking (approximately 70%), and 90% identify as Mexican. The goal of CKA remains to help parents understand academic expectations for college, improve communication with schools, increase engagement by parents, and ultimately prepare students for postsecondary opportunities. The CKA believes that early college preparation will lead to greater opportunities for postsecondary enrollment at four-year universities.

Serving approximately 100 families each year, the CKA consists of weekly, two-hour workshops held over a twelve-week period each spring semester. Families are recruited with the help of school district administrators and school/parent liaisons, at school events, and via referrals from past participants. All families have children who are currently enrolled in one of the district’s elementary schools. The workshops are delivered in both Spanish and English so that families receive college knowledge in their home language. The program also includes two campus visits to the local university, where families learn more about university culture and academics. The program ends with a final visit to the university, where parents are honored with a graduation ceremony for their program completion, commitment, and time.

The CKA has utilized funds of knowledge as a pedagogical framework since it began in 2004. That is, the 12-week curriculum is designed to honor and build upon families’ prior home and cultural knowledge while also expanding that knowledge around college-going topics. Thus, the college knowledge shared during the CKA at times informs the program and at other times is cultivated because of the program. Funds of knowledge sharing become a reciprocal process within the CKA between staff, faculty facilitators, community members, and other family participants.

9. Participants

In an effort to include as many initial CKA participants as possible, data collection occurred over the course of two years (spring 2015–spring 2017). Our research team conducted a total of 39 interviews with 54 individuals, which included 12 individual administrator interviews and 20 family cluster interviews (10 English and 10 Spanish interviews) and seven individual student interviews. We did not ask participants to share gender identity and thus do not report on that information here.

Administrator interviews offered important details about the history of the program and evolution of the pedagogical approach. Approximately half of the family interviews consisted of an individual interview with one parent, while the other half of the family interviews included more than one participant, inclusive of parents, a grandparent, and children both in college and high school. Participants were recruited from the cohorts of families who participated during the first five years of the program (2004–2009), as we wanted to understand how family perspectives about education and college-going shifted over time and into college choice and transition. While nearly all parents participated in CKA only once, one mother participated in 2006 and again in 2008, and one other mother participated four times (2006, 2011, 2014, 2015). Each of these mothers attended CKA during the years in which their children were eligible for participation (e.g., K-5). The majority of families had between two and four children, some of whom had already graduated from high school. We attempted to conduct individual interviews with those students, given the broader focus of the research project on college preparation and college going. The individual student interviews consisted of students who were either in high school and planning for college choice or enrollment, or currently enrolled in college at the local university or out-of-state institutions. We draw specifically from the family and student data for this paper, which includes a total of 27 interviews with 42 participants.

All but one of the parents and family members who participated in the interviews held what would be considered working-class or volunteer employment roles. For instance, parents worked in construction, truck driving, cleaning homes, administrative assistant roles like accounts receivable, and/or volunteering at their children’s schools or local churches. One mother had returned to college after participating in CKA and earned her bachelor’s degree and later master’s degree and was working as a social worker.

10. Data Collection

Interviews with parents, family members, and individual students were conducted in either English or Spanish, depending on the preferred language of participants. Interviews consisted of both English and Spanish as participants switched back and forth between the two languages. Interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format, which provided space for participants to engage conversationally and with flexibility [48]. Interviews ranged anywhere from thirty minutes to over two hours, with some interviews requiring a second visit to complete the interview. Research team members offered to meet families in an interview location most comfortable and convenient for them, which took place in families’ homes, local libraries, and local schools. We focused on families’ continued development of funds of knowledge and perspectives about college. Questions about families’ funds of knowledge were informed by decades of previous research and literature on the topic. These questions focused specifically on how they are utilized and shared (i.e., transferred) within the family unit, with social networks, and within the community. We sought to understand how college decisions were formed over time, how families’ funds of knowledge influenced the evolution of family perspectives about education, and the long-term influence of the CKA. To understand the evolution of family perspectives, we began interviews with talking about family history, inclusive of educational, job, and home practices, as each has been shown to influence the formation of beliefs about college in Latine families [4,5]. We then asked about involvement with the CKA and practices related to college preparation. Interviews with individual students focused more on college preparation, choice, and transition. To our knowledge, this study represents one of the first to engage with families involved in college outreach from the time of initial college outreach participation through college choice, transition, and enrollment processes.

11. Data Analysis

Data analysis was organized in multiple steps. After transcribing the audio files, the first analysis step included four members of our research team reading through the interviews conducted with staff, administrators, and family members to establish an initial set of open or inductive codes across interview types. Doing so ensured the research team was communicating clearly about the coding process, agreeing on the initial codes, and developing inter-rater reliability. A priori categories [43] were also established for deductive coding around key funds of knowledge concepts including educational pathways and histories, immigration histories, labor histories, educational lessons, educational ideologies (i.e., perspectives about education), role of cluster households, community networks, and college aspirations in an effort to assist with thematic coding. The process of inductive and deductive coding made way for expanding upon the preliminary codes and moving into axial coding, or grouping connections across codes and categories [43]. We then uploaded the groups of codes into NVivo 10 for further analysis. Each transcript was analyzed in NVivo 10 by two members of our research team. The two team members would debrief after analyzing the transcript to ensure consistency across coding.

Axial coding allowed for the research team to collapse and combine codes, resulting in a total of 12 primary level codes and 74 secondary level codes. Finally, we moved into an additional step of second-level elaborative coding [49]. This allowed us to utilize our framework to inform the coding of data in a cohesive way understood through the five types of system interactions: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem [18]. Second-level elaborative coding was particularly useful in understanding the network of relationships and structures in which families were embedded. We accomplished this second-level coding (Saldaña, 2009) by creating data tables [43] that aligned with each system. From there, we were able to map specific examples from the data to each system while also adding explanatory descriptions about each system into the data table. We have included three examples from our data table (see Table 2 below) to illustrate how the research team worked through applying analysis notes and framework concepts to the quotes and themes. While not all of the quotes were included in this article, Table 2 highlights examples of how individual codes are then understood through an analytical framework.

Table 2.

Sample Analysis Data Table.

12. Trustworthiness

Establishing trustworthiness in a community-based research (CBR) study begins with trust and collaboration [47]. CBR calls for researchers to partner with the community in each step of the design and dissemination process and work to establish ongoing trust and respect through these processes [50]. The principal investigator (Kiyama) has worked with the CKA in an evaluation and research capacity since the program began. This sustained relationship has cultivated an important trustworthiness strategy of “prolonged engagement and persistent observation” [44] (p. 250).

In this particular study, our partners included the staff who oversee the CKA. We engaged our partners in each stage of the research process, which included developing research questions, engaging in data collection, and formulating an analysis plan. As previously noted, the CKA staff have also been involved in the dissemination of data, including local and national presentations and co-authoring research briefs and journal articles. This type of partnership establishes an opportunity for both “member checking” and “peer review or debriefing” which allow us to check the research process and clarify findings with CKA staff [44] (pp. 251–252). Involving our partners in each step of the process not only provides a diversity of perspectives and an opportunity for transparency and to debrief with peers, but also centers community knowledge as the most important driver of that process [50,51].

13. Positionality

The authors for this current article represent three members of a larger research team that over time included current and former doctoral students, the PI (second author), and CKA staff members. Lopez and Sarubbi were doctoral students during the time period when data was collected, analyzed, and when this article was initially drafted.

Lopez is a Latina scholar of Mexican–American heritage. As a first-generation college student and soon newly conferred doctora of the academy, the story of her academic journey is greatly influenced by her single-parent father. She shares that her educational legacy is part of her father’s legacy, their family’s legacy, their friends’ legacy, and their community’s legacy. This connection inspires her to center the lived experiences of historically marginalized parents and families to understand and honor their legacies of engagement, sacrifice, and commitment to their children and their communities.

Kiyama has dedicated her career—as a professor, former student affairs staff member, and various leadership and administrative roles, to advancing equitable access to education, particularly for minoritized and refugee communities. This work has largely taken the form of research and various projects directly involving parents and family members in an effort to better understand the role they play in cultivating college-going opportunities for their children. As a Mexican–American and first-generation college student who went through K-12 education in a very rural area with few college-going support systems, she is committed to advancing this work through research, practice, and policy changes.

Sarubbi identifies as a white, female, first-generation college student and foster care alumni. She brings each of her intersecting identities, lived experiences, and personal philosophies to this scholarship. Sarubbi acknowledges how both her privileges and unique perspectives inform this work and is intentionally committed to centering equity, antiracist, and asset-based methodology in her research and practice. As such, she takes an inclusive and advocacy approach to the definition of family and community engagement and works alongside partners to scale measurable and equitable change.

14. Limitations

This study offers many contributions with respect to family and community engagement and college-going for Latine youth. However, it is not without limitations. While we interviewed every director and coordinator involved with CKA since its inception and contacted as many families as possible from the early years of the program in 2004–2009, some families were not invited to participate due to inconsistent data tracking of CKA participants. Additionally, while we do have some data on the college-going paths of current college students who participated in CKA with their parents in 2004–2009, the sub-sample for this part of the data collection is small. The program itself has served over 1500 families over the last 20 years. Thus, our data represents only a fraction of total participants. And although we offer an ecological systems description for this paper, the study itself was not designed as a systems analysis. Thus, it will be helpful in the future to understand how various systems, particularly within Latine communities, influence college-going and family engagement. Finally, we worked intentionally to include CKA staff as co-PIs and active partners in the data collection, analysis, and dissemination of findings—in alignment with community-based research methods. However, parent and student participants were not engaged as research partners in the same way, thus limiting the full possibilities of community-based research within this particular study.

15. Findings

The findings demonstrate how parents mobilized their funds of knowledge through social interactions across multiple systems to support educational attainment for their children. We position CKA in our findings, not for the purpose of a program evaluation. Rather, our goal is to illustrate how families’ social interactions in a college outreach program setting like CKA can influence the interactions and relationships across a network of ecological systems that surround Latine parents and their children. Participation in CKA, with its culturally responsive programming, provides a communal setting for families to build on their accumulated beliefs about engagement. Further, the social interactions with CKA program staff and fellow parents provided opportunities for families to participate in negotiation and dialogue regarding their children’s education. Quotes from parents (participant names have been changed to pseudonyms) illustrate how funds of knowledge are actualized—families not only acquired college knowledge but also developed confidence, increased their support capacities, extended their social networks, strengthened their “orientations to action” [16] (p. 9), and converted their college aspirations from dreams to tangible college plans. Such meaningful interactions provided the social context to motivate families to activate and transfer their knowledge and nontraditional forms of capital outside the CKA system. Parents mobilized their funds of knowledge across their networks, sharing and receiving college-going information, to reciprocally develop and nurture relationships of engagement and support for themselves and for their Latine community as they sought to influence the postsecondary educational pursuits of their children. Findings demonstrate Latine parents’ critical advocacy and agency across their community settings. Our findings are organized by system level relative to the position of the child as the focal individual.

16. Microsystem—Expanding Funds of Knowledge within Family Units

Motivated by their involvement in CKA and the specific college knowledge they learned, families were able to expand on their funds of knowledge, positive messages, and lessons they were already sharing in the household to support their children’s educational pathways. When asked about the impact of CKA, one parent discussed how their involvement increased their own confidence and capacity to support their child through the college-going process.

Through the years, as [our son] went to middle school and then to high school, we made sure he targeted the requirements [CKA] discussed. So when he got to the doorstep, they wouldn’t turn him away and say, ‘Well, you haven’t done this or this, or you have to go take it for the summer to fulfill the requirements’. So we had everything pretty well set when he got to his senior year.(Carlos, father)

In addition to this awareness of specific college-going processes, another parent shared how involvement in CKA changed the way she talked about college and affirmed her child’s aspirations from an early age.

I learned in [CKA] to say, ‘what do you want to study when you grow up?’… To tell them, ‘what will you be when you go to college?’ It was very affirming when they were little.(Andrea, Mother)

A fund of knowledge lens helps us to understand the importance of extended relationships and “cluster households” within their community networks—that is, families and households that support one another through sharing knowledge and resources [37]. Parents discussed how involvement in CKA impacted not only the immediate household but also their extended family structure in the microsystem.

We actually recruited my brother…for this year’s program. My niece, the oldest, is in Kinder right now, so she kind of doesn’t have an idea yet, but I told him, ‘You know what? It is never too early. You have to start doing this as soon as possible’.(Cynthia, Mother)

The examples shared by parents demonstrate the ways in which they developed beliefs about college in the home and were informed by the content learned in CKA. These beliefs built upon their existing funds of knowledge.

17. Mesosystem—Activating and Sharing Funds of Knowledge across Communities

Parents also shared how they used the additional college knowledge and confidence acquired from their participation in CKA to move their own educational engagement from the household to additional forms of self-advocacy for their children in the school setting. In this example, a parent sought out a partnership with her child’s teacher to create a more supportive, interconnected environment for her child between the microsystem structures of the school and home.

Once at the beginning of the year I requested a conference, and…a teacher arrived during the lunch hour, all upset, and said, ‘Why are you requesting a conference so early if classes just started?’ And I said, ‘Well, because I want to know how you are going to work with my son and I want to know what I can do to work with him’. I ask her first, because I will not ask her at the end when it is too late…. [But] when I came to speak to a teacher [and] she would say to me, ‘I only have five minutes to talk to you’. …I say, ‘Sometimes my character is not that I’m a fighter, but I have to be strong because I have to see, what is the matter with my children?’(Berenice, Mother)

Outside of their family microsystems, the Latine parents also mobilized their funds of knowledge in their neighborhoods through participation in CKA’s parent mentoring and networking program, Familias Aliadas (Familias Aliadas is a pseudonym). The group is a family-led initiative and is comprised of parents who have already gone through CKA and now volunteer to develop relationships with other families in their communities and help them navigate the process. Familias Aliadas has become a knowledge-sharing network for families and a crucial connecting piece between other system interactions. One parent discussed how their participation in Familias Aliadas influenced their intermediary position as advocates who not only promoted their own child’s success but who also directly interacted with the parents of their child’s neighborhood friends and peers to share knowledge and promote the engagement of Latine families in school spaces.

No, we are not college graduates…but we believe you don’t need to be graduated from college to be an advocate. Advocates are the heart of the community. The advocates are the middlemen. They are the ones delivering the tools. If I or any other person didn’t have the opportunity to graduate from college, we aren’t going to just stop dreaming. Of course we are going to continue dreaming, and we will continue communicating with other parents.(Lucinda, Mother)

Sharing resources and knowledge within communities is a central concept of the funds of knowledge framework. Not only did families in the study share this knowledge in informal ways, they organized a formal network, Familias Aliadas, through which college knowledge was passed to families who could not attend the CKA. Similarly, a father shared how he and his wife engage with Familias Aliadas to connect with the families of their son’s friends to support their educational attainment.

In [Familias Aliadas], that is our goal right now, to help—well, to help our son’s friends…Sometimes [their parents] are a bit lost; they don’t know what to do in order to make their children go to college. So, then we must connect with the parents so that they acquire the information so their children can attend college. That they don’t just stay with high school, but that their children are able to have a career.(Angelo, Father)

As parents embedded themselves as intermediaries across the boundaries of different microsystems for the child, such as the home, school, and neighborhood settings, they activated and shared their knowledge with a deep commitment to the educational success of not only their own children but of other Latines in their surrounding community. Parents were able to extend college-going knowledge and influence other families’ engagement and support of their children. Such mesosystemic interactions present a crucial navigational strategy for how Latine families developed and sustained their rich repositories of knowledge.

18. Exosystem—Mobilizing Funds of Knowledge for Educational Opportunities in School District and Beyond

There were also instances when social interactions in the CKA setting inspired influences in the exosystem. One parent shared how several mothers have utilized the CKA space as a time and place to raise educational concerns and discuss what changes they would like to see their school district make.

There are many things we’d like as parents for the district to change…They have many fails; first, the teachers and resources. I didn’t see it when [my son] was younger, but now that he’s older, I’ve seen it because I’m not the only mother saying it…Some mothers from the same school district get together in the [CKA] program, and all of us say, “Why don’t we do something”?(Consuelo, Mother)

In addition to the acquisition of college knowledge, the parents’ involvement in CKA presented the opportunity for them to develop supportive social relationships and find commonalities in their concerns with their respective schools, highlighting how these might be more systemic issues than isolated concerns within an individual school structure. In doing so, these mothers found the opportunity and support to think beyond the microsystem interactions and envision how they could also help their children by collectively pushing for change in the district at-large.

In the quote that follows, Berenice discussed her personal experience with the challenges that Latine immigrant families face in their transition to the United States and her motivation to volunteer in a community organization that has a broader positive influence in mitigating those issues for other Latine families in the city.

A few years ago I worked for [Our Community Connection], which was also a program supporting parents with children. I worked with them as a volunteer…I tried because I said, ‘Well then. For me, the system was very new, right? How can I help them?’ In the first place, the language was not my forte, and then I did not know the programs. I did not want my children not to have the opportunities. And I knew that there was [help], but sometimes where, how, with whom, and who to ask can be difficult.(Berenice, Mother)

Similarly, below Andrea shared her desire to support her community at-large. Both Andrea and her husband had been very active with other CKA families and within their community. However, she mobilized her knowledge and resources at the local political level. In the following excerpt, the parent speaks as a representative of families who have been historically marginalized and who need access to community resources such as adult education to better themselves, which then helps them better support their children.

I went to meetings to represent; I met legislators…I was very involved in keeping the adults education [in the community]. I started taking [community college] classes as they were free. I took Publisher classes and the Neighborhood Coordinator class. I always wanted to be the bridge between the necessity and the resources…Always everything that has to do with human rights, because I can’t stand injustice. I cannot. And I have been made fun of because I speak English with a heavy accent…but I don’t care if I am undocumented, you do not treat me like that.(Andrea, Mother)

In the two aforementioned examples, CKA parents discuss how they engage at the exosystem level to be a part of change efforts and resource allocations that support Latine families. While earlier findings in the mesosystem level mentioned how CKA parents engaged with other Latine parents beyond the organizational boundary, parents’ actions in this current level differ in that they were not attempting to be the interconnections between microsystem structures like the home and school, nor were they choosing to interact with parents of their children’s friends and peers on a direct, individual basis. Rather, their efforts were expanded to contribute to change at a higher, broader system level for a whole district or city community. A fund of knowledge lens provides understanding of agency that was activated for parents as they advocated in different spaces. CKA helped parents to connect that advocacy to similar actions within postsecondary spaces. Parents demonstrated an understanding that such efforts would ripple through families and indirectly support the postsecondary educational success of their children as well. The parents’ experiences also link to the macrosystem, as demonstrated in the previous mother’s description of discrimination based on language or documentation status.

19. Macrosystem—A Space to Understand and Critique Systemic Barriers

As Latine families’ navigate systems related to educational attainment, their social interactions can be influenced by macro-level forces that include discrimination based on language and race, segregation, poverty, and multiple other deficit perspectives. The College Knowledge Academy recognizes and situates families’ experiences within the larger social climate and supports them in the continued expansion of their funds of knowledge and positive perspectives about college that can help them mitigate negative external messaging. This happens through culturally validating program components, often held in Spanish; connection to community resources to help navigate structural and systemic barriers; collaboration between families, CKA staff, and school district leadership; and reciprocal relationship-building across these various communities.

One mother discussed how racial discrimination and segregation existed in her community. She identified the social interactions through CKA as valuable opportunities for parents to engage in dialogue about the social inequities Latine families face and to be affirmed as meaningful, positive contributors to their environments. Specifically, families were able to connect informally during program breaks and before and after the program to not only share educational strategies but also discuss how social inequities impacted them. Families were motivated to become or remain more involved in their children’s education, which shapes the patterns of social interactions the parents engage in at other system levels.

To be honest with you, there is still segregation. There is still discrimination that still happens on the streets. I mean, I’ve been a victim of it. There’s a lot of hate unfortunately, and you cannot run away from that…There’s a huge thing about segregation and hypocrisy in the Latino community, and there’s a lot of my own people talking about how we always get run over and we’re always under the bottom. But being in CKA let us know we were all equivalent…So, I think that was the biggest thing that being in [the program] could have done was make you feel that you’re equal because I think too often things happen that people feel like they’re just underappreciated or just not used at all. That’s pretty much what drives them away from being involved.(Berenice, Mother)

Another father addressed the importance of being active within their communities as a matter of supporting one another given the discrimination around race and language that he has witnessed and experienced. In 2000, Arizona—in which CKA and these families reside, passed Proposition 203. Prop 203 repealed bilingual education in schools and required English language learners be taught through structured English immersion. As of 2023, the state remained the only one in the country with English-only legislation still in place.

Yes, we help in everything we can in the school when there’s something to do. We need to be active because…that’s a way for Latinos to succeed. Just imagine if they’re afraid of us now, like helping youth. I was watching in the news that an event was going to start in a school, and one of the teachers started speaking in Spanish, and an American stands up and says, “English only, USA”. And I think that’s a lack of mind. Why only one language?(Octavio, Father)

While only alluded to, Octavio’s reference to them (Americans) being “afraid of us” suggests an understanding of the macro-level power dynamics that can permeate ecological systems and the ways in which the racial and linguistic presence of Latine families may pose a threat to those in presumed power. This understanding influences the social interactions Octavio engages in, as well as how and with whom he mobilizes his funds of knowledge in support of educational attainment for his child and his community’s children.

Another parent mentioned how interactions in CKA helped her understand that socioeconomic status did not have to be an impossible barrier to college access.

When you go to CKA, you understand that not all of the students need…to be more rich or more poor to have access to financial aid or grants… [CKA] does make a difference, and I now think so much more different than before I went.(Andrea, Mother)

Parents were encouraged to question economic and knowledge systems and privileges within. In turn, their change in thinking influenced how they engaged in planning for college with their children and how they approached interactions with their children’s schools. Thus, their foundation of valuing education was enhanced by both CKA and their time visiting the university campus. Likewise, the earlier quotes in this section illustrate parents’ understanding of broader social and political systems and how these systems influence opportunity. While the purpose of CKA is not necessarily to teach about these social and political systems, it does provide families a space to make connections between various structures of opportunity (e.g., education and immigration policy or education and language policy). What is demonstrated is a confidence of knowledge within their macrosystem—a mobilization of their funds of knowledge. Their quotes also offer a transition into discussions of the chronosystem. The parents’ interrogation of systemic inequities opens up the possibility to envision and enact influence and formalize future educational possibilities.

20. Chronosystem—Shifts of Ecological Systems over Time

Continuing with the illustrations of Andrea and Rogelio, we note that many significant transition points for the Latine families involved in CKA centered around discussions about the change from conceptualizing college as less of a dream to more of a tangible reality and plan for their child’s future. Thfe chronosystem lens provides a framing to understand these shifts in realities and plans over time.

Once we started going to [CKA], it started really sinking in. It was like, “Okay, this makes sense now”. The [university] to me has always been a big mystery because we grew up around it, but never really got involved in it. It was a place that … you couldn’t do it is the way we saw it. It has this imaginary gate area—or this fence. It’s almost like a barrier sometimes that most people would see as like, “Oh, yeah, it’s a beautiful place, but you know what? We cannot be there”. And that’s what being in CKA, I think, opened up is that you start seeing the reality of it.(Rogelio, Father)

Likewise, Andrea noted,

Now we know that [college] is not a dream like a lot of people seem to think. It is a plan. I believe that is very important and that this has changed a lot of people, but it would not be as possible without [CKA’s] information.(Andrea, Mother)

These examples demonstrate a shift in the future possibilities of the chronosystem. This conceptualization of college as an accessible reality and not a dream would be considered a normative chronosystemic transition that often exists for white families with the dominant forms of social and cultural capital that position college entry as an assumed next step during the lifespan of the developing child. Conversely, Latine families face legacies of social and educational inequities that continue to persist today. While Latine families are strongly invested in supporting their children’s educational aspirations [29], the social and familial networks they use to gather and mobilize support and resources and to construct conceptualizations of college are often not recognized or validated in the dominant culture of various system structures. Thus, engagement in CKA becomes an important chronosystemic shift, or the beginnings of converting funds of knowledge into forms of capital, for families as parents develop supportive social relationships, internalize the program’s messaging, and acquire college information that helps them further extend educational opportunities for their developing child and their communities. The two previous examples illustrate an expected transition within the chronosystem over time given the family’s participation in CKA. However, the next example concretely illustrates how participation in the CKA in 2004 resulted in a change in educational attainment and opportunity over a period of 15 years. Here Tanya, a single mother with two high school children, shared her journey of returning to her own college education, something that she shared was inspired to do after participating in CKA. Tanya returned to complete her bachelors and masters degrees (in 2011 and 2012) and held high expectations that her children would do the same. In the following conversation, her son talks about Tanya’s accomplishments through visuals—photographs of her graduations, and Tanya responds by telling them she expects the same from the two of them.

- Son:

- Now, we got her picture in our office…. A hall of fame.

- Mother:

- Yeah.

- Son:

- A hall of fame graduates I should say (referring to his mother’s graduation photos).

- Mother (speaking to her children):

- It is a big deal, guys, so don’t cheat me out of that (referring to both their graduations and their photos in their hall of fame.)

Although she participated in CKA to learn more about college-going for her then, elementary-aged children, what resulted in a change in the chronosystem for the entire family. Tanya mobilized and converted her funds of knowledge into concrete degree attainment, setting a path for her children to do the same.

21. Discussion

This paper is predicated on the assumption that Latine parents value education and engage in the educational access and success of their developing child through a variety of behaviors and activities based in cultural practices that can be recognized and understood through the funds of knowledge framework [4,5,37]. As we traced the patterns of how families’ funds of knowledge are utilized, mobilized, and transferred [38] within the various ecosystems in which they interact and influence in support of their children’s educational attainment, we acknowledge the CKA as an important intersecting influence in the families’ ecological environments. What is also clearly demonstrated is that the Latine families in this study were already in possession of rich cultural knowledge and resources, which shaped their agency, advocacy, and resiliency to mobilize within various ecological and educational spaces. The findings from this paper also support the extensive body of scholarship [5,14,22,25,28,33], demonstrating that Latine parents have a foundation of cultural and historical knowledge, rich histories of advocating for their children’s educational opportunities, and a strong sense of agency that helps to shape the building of college knowledge on that foundation.

Specifically, one important theoretical contribution of this paper is understanding Latine parent engagement with college-going processes through the combined theoretical lens of funds of knowledge [20,37] and ecological networked environments [17]. The overlapping or networked systems, as defined by [19], became the environments in which college-going practices flourished and were shared with others. Specifically, within the microsystem and mesosystem, parents shared college-going knowledge within their family units and community, respectively. Within the exosystem, parents mobilized funds of knowledge in partnership with other families to advocate for education opportunities within their local school district and beyond. The macrosystem became a space to understand and critique the systemic barriers that impacted college-going opportunities, and finally, within the chronosystem, we saw how the ecological systems shifted over time, thus changing structures of educational opportunity for Latine families. As demonstrated, each system arises from a setting where individuals engage in social interactions, and the system level is determined by the position of the focal individual relative to those interactions.

The pedagogical approach utilized by college outreach programs like the College Knowledge Academy builds on the foundation of valuing education and funds of knowledge of Latine families and offers them opportunities to develop college-going knowledge and additional supportive relationships that can increase their opportunities to postsecondary access and success. This type of educational advancement is often considered limited to the scope of micro- and mesosystemic shifts in how parents and children engage with one another and in the school environment. As findings have demonstrated, developing their children’s increased postsecondary educational access also exists and operates in a network of multiple ecological systems for families.

In the case of CKA parents, their initial participation in the program helped to bolster college-going knowledge and provide interaction opportunities for families to engage in educational discourse and practice. Further equipped with this knowledge and coupled with their existing funds of knowledge, the parents became sources of college knowledge for other families, thus creating a broader network of college knowledge and support for other Latine families and their children.

There are many parallels between the experiences of Latine parents in the CKA and Latine families in the Padres Lĺderes program that Duran and colleagues [33] wrote about. For instance, both programs were developed with families’ linguistic and cultural funds of knowledge as a pedagogical foundation. Families in both studies demonstrated sophisticated advocacy skills as they engaged their local school district’s political processes (as was the case in the Duran [33] article). Latine parents in the current study also demonstrated sophisticated organizing and advocacy skills as they created a formal network, Familias Aliadas, to share educational information (mesosystem) and how they leveraged what they learned in CKA to ensure their entire family had access to postsecondary education (chronosystem).

At the exosystem level, families interacted to expand and nurture their social networks of exchange and their orientation to action. Calabrese Barton et al. [16] discuss orientation to action as representative of the “resilience to hardship” that is often a form of nontraditional capital among families of color who have faced many dangerous and inequitable life circumstances (p. 9). This resilience is born from difficult life experiences wherein families learn the larger role of social, economic, and political factors (i.e., macrosystem forces). In response, CKA parents expressed desires for and engaged in behaviors invested in greater socio-political and economic change that may positively influence not only their children but the Latine community as a whole over time. In such instances, we understand that families are not only engaged in their immediate households and schools when it comes to education but also employed rich cultural resources at other structural levels.

In short, the Latine families have agency. As demonstrated by the families in our study and in the various studies [4,5,22,25,28] that have set the foundation for this work. Latine families have power. And while the multiple engagement or outreach programs, like CKA, are instrumental in helping to cultivate their funds of knowledge [4,33,34], the organizing and advocacy power of these Latine parents exists before, during, and well after their participation in such programs.

22. Implications for Practice

Viewing families’ mobilization of funds of knowledge ecologically has important implications for both research and practice. We turn first to implications for practice. The findings from this study demonstrate that these Latine families engage within networks of multiple, interrelated systems to support their children’s postsecondary educational attainment. The various levels of engagement can be seen in immediate familial relationships, as well as the interactions in schools, districts, neighborhoods, and communities at-large. Therefore, when we consider where programming for and with Latine families resides, we must work to extend such programming across entire community spaces. College-going information must not be limited to postsecondary admissions offices but shared within community spaces near families’ homes, within community centers, and within children’s elementary schools to begin cultivating college-going pathways across community spaces and networks.

The findings also recognize that programs like CKA play a vital role in families’ ecological environments and can have positive influences beyond the immediate interactions of home and school. An example of this broader influence includes families’ expansion of networks of college knowledge and support for other Latines who do not directly interact with the outreach program. Another example is found in families’ involvement in socio-political change efforts to address systematic issues that can influence the educational access and success for Latines in a whole district or community. This suggests we should continue to support parents as active knowledge holders, as their engagement is not bound by formal involvement structures. Schools at all P-20 levels need to involve parents and families in ways that honor their knowledge, cultures, concerns, and diverse forms of engagement. Likewise, schools should offer space for families to gather and share college-going experiences, questions, and information just as was illustrated with Familias Aliadas.

Finally, the CKA was intentionally developed utilizing the asset-based framework of funds of knowledge. Other outreach programs, particularly those serving minoritized communities, would benefit from developing curriculum and outreach activities informed by asset-based, culturally affirming frameworks.

23. Implications for Research

We have understood through previous research that family and community are major sources of support and influence for the developing child. By drawing on the constructs of EST, we add a clearer topological perspective of how and with whom these Latine families and communities interact and mobilize their funds of knowledge. The more nuanced understanding of this social influence and support can inform future research and practice involving the educational engagement of Latine families. While the field has continued to understand the role of familial engagement in the college-going process, there is more to unveil about the particular ways in which these communities navigate systems that have historically been barriers to success. We recommend that future research take up a systems analysis approach, examining how the systems that Latine families interact with influence college-going, particularly over P-20 pathways.

Although there is some research demonstrating that early college outreach programs do influence college-going for youth, more research needs to be conducted in this area. For instance, we do not know enough yet about how college outreach programs may yield actual admissions or enrollment gains for institutions, particularly for students from minoritized backgrounds. It would be beneficial to track college outreach program participants over time to understand their college-choice decision processes and ultimate matriculation path.

Finally, future research should investigate how other college outreach programs influence and expand on Latine families’ mobilization of funds of knowledge and their extended interactions of educational engagement across ecological structures. Such research can help practitioners situate their programs in the surrounding environment in ways that help cultivate pathways across the ecological systems to impact both individual and collective educational experiences.

24. Conclusions

In this article, we sought to expand current understanding of Latine parent engagement by examining how families’ funds of knowledge intersect with the knowledge and relationships gained from a college outreach initiative to influence families’ ecological environments. Through the combined framework of EST and FoK, we trace how Latine families and communities support the postsecondary education of future college students within multiple contexts. The result is a more nuanced understanding of how Latine families who have participated in a college outreach program designed from a funds of knowledge framework extend their educational engagement across different system levels. We identify distinct patterns of social interactions and mobilization of knowledge and resources across the different system levels. We also demonstrate how families are committed to not only supporting their own child’s educational opportunity but also extending educational opportunities for their communities. Finally, our work helps to further situate the role and influence of college outreach initiatives for Latine families. Engagement in a college outreach program is positioned as a crucial chronosystemic shift that has direct and indirect influences throughout families’ ecological environments. Latine families within this particular college outreach initiative acquired college knowledge and encountered affirming, culturally rich social interactions through which they developed their families’ educational goals and cultivated a greater sense of agency in education. These ecological influences, coupled with the cultural foundations and funds of knowledge within Latine families function as significant transition points that change how families, then navigate the other system-level interactions and spaces and move towards educational success over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—S.L.L. and J.M.K., Funding Acquisition—J.M.K., Data Collection—J.M.K. and M.S., Data Analysis—S.L.L., J.M.K. and M.S., Writing—original draft preparation—S.L.L., Writing—reviewing and editing—S.L.L. and J.M.K., Supervision—J.M.K., Project administration—M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Denver PROF Grant. Project Funded: “Developing a College-Going Culture in Latina/o Families: Exploring the Influence of Funds of Knowledge in Family Outreach Programs”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Denver, approved 2 February 2015. Project # 576328-5.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dyce, C.M.; Albold, C.; Long, D. Moving from college aspiration to attainment: Learning from one college access program. High Sch. J. 2013, 96, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.E.; Torres, K. Negotiating the American dream: The paradox of aspirations and achievement among Latino students and engagement between their families and schools. J. Soc. Issues 2010, 66, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsford, S.D.; Holmes-Sutton, T. Parent and family engagement: The missing piece in urban education reform. Lincy Inst. Policy Brief 2012, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyama, J.M. College aspirations and limitations: The role of educational ideologies and funds of knowledge in Mexican American families. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 47, 330–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyama, J.M. Family lessons and funds of knowledge: College-going paths in Mexican American families. J. Lat. Educ. 2011, 10, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Diamond, J.B. Despite the Best Intentions: How Racial Inequality Thrives in Good Schools; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru, A.M. When new relationships meet old narratives: The journey towards improving parent-school relationships in a district-community organizing collaboration. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2014, 116, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pstross, M.; Rodriguez, A.; Knopf, R.C.; Paris, C.M. Empowering Latino parents to trans-form the education of their children. Educ. Urban Soc. 2016, 48, 650–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, A.M.; Takahashi, S. Disrupting racialized institutional scripts: Toward parent-teacher transformative agency for educational justice. Peabody J. Educ. 2017, 92, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Castellanos, O.; Gonzalez, G. Understanding micro-aggressions impact on the engagement of undocumented Latino immigrant father engagement: Debunking deficit-thinking. J. Lat. Educ. 2012, 11, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquedano-Lopez, P.; Alexander, R.A.; Hernandez, S.J. Equity issues in parental and community involvement in schools: What teacher educators need to know. Rev. Res. Educ. 2013, 37, 149–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Castellanos, O.; Olivos, E.M.; Ochoa, A.M. Operationalizing transformative parent engagement in Latino school communities: A case study. J. Lat. Lat. Am. Stud. 2016, 8, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasis, P. Latino immigrant parents and schools: Learning from their journeys of empowerment. J. Lat. Educ. 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivos, E.M. The Power of Parents: A Critical Perspective of Bicultural Parent Involvement in Public Schools; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley, D. Community Organizing for Urban School Reform; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese Barton, A.C.; Drake, C.; Perez, J.G.; St Louis, K.; George, M. Ecologies of parental engagement in urban education. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. A future perspective. In The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 3, pp. 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, J.W.; Neal, Z.P. Nested or networked? Future directions for ecological systems theory. Soc. Dev. 2013, 22, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, N.; Moll, L.C.; Amanti, C. (Eds.) Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in House-holds, Communities, and Classrooms; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]