Affective Experiences of U.S. School Personnel in the Sociopolitical Context of 2021: Reflecting on the Past to Shape the Future

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. K-12 Education and Politics

3. Affective Experiences of School Personnel

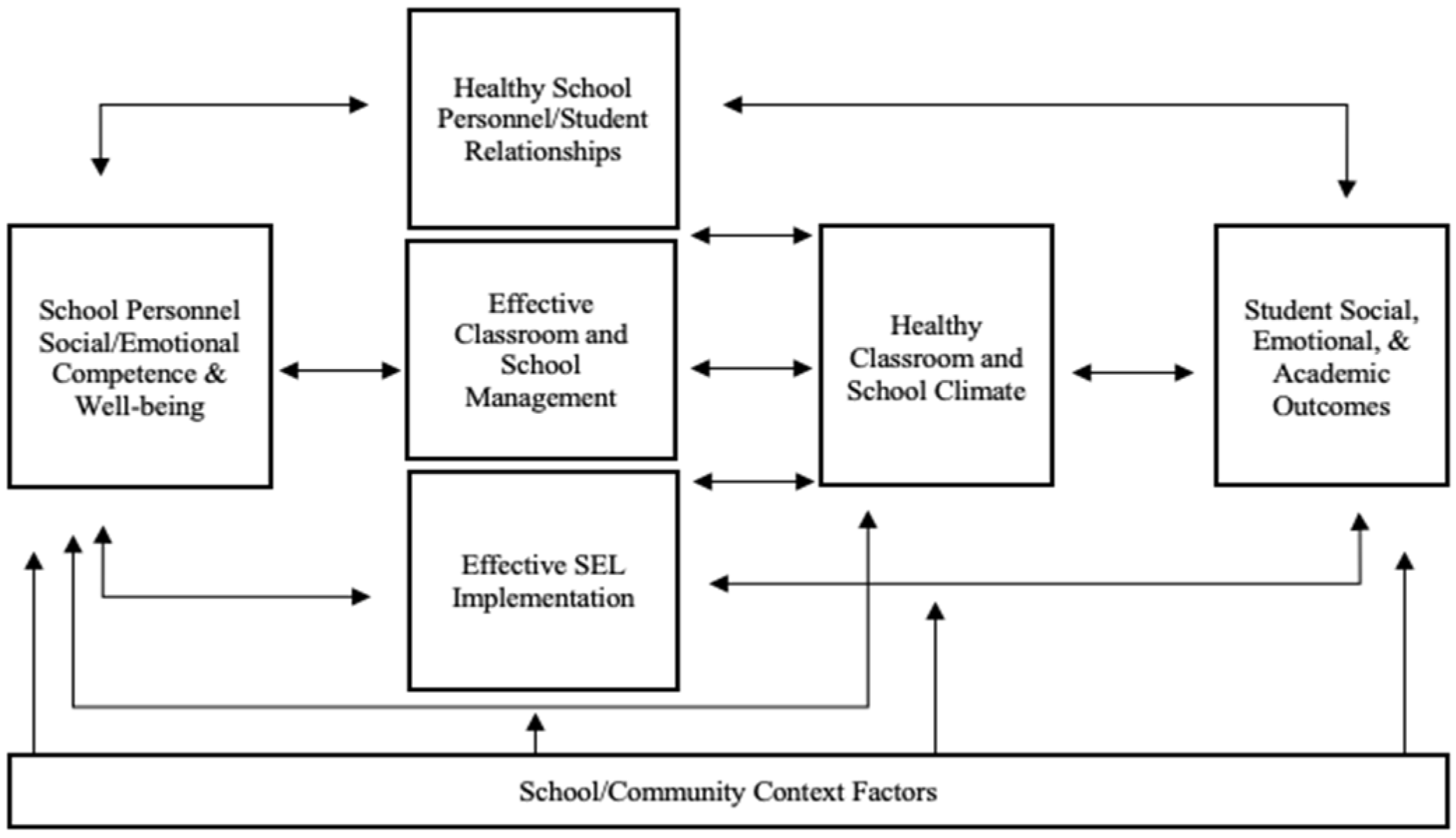

4. Prosocial Classroom Model

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Study Design and Data Collection

5.2. Participants

5.3. Measures

5.3.1. School Personnel Affective Experiences

5.3.2. Sources of Stress and Joy

5.3.3. Crisis Response Educator SEL Survey

5.4. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Frequencies

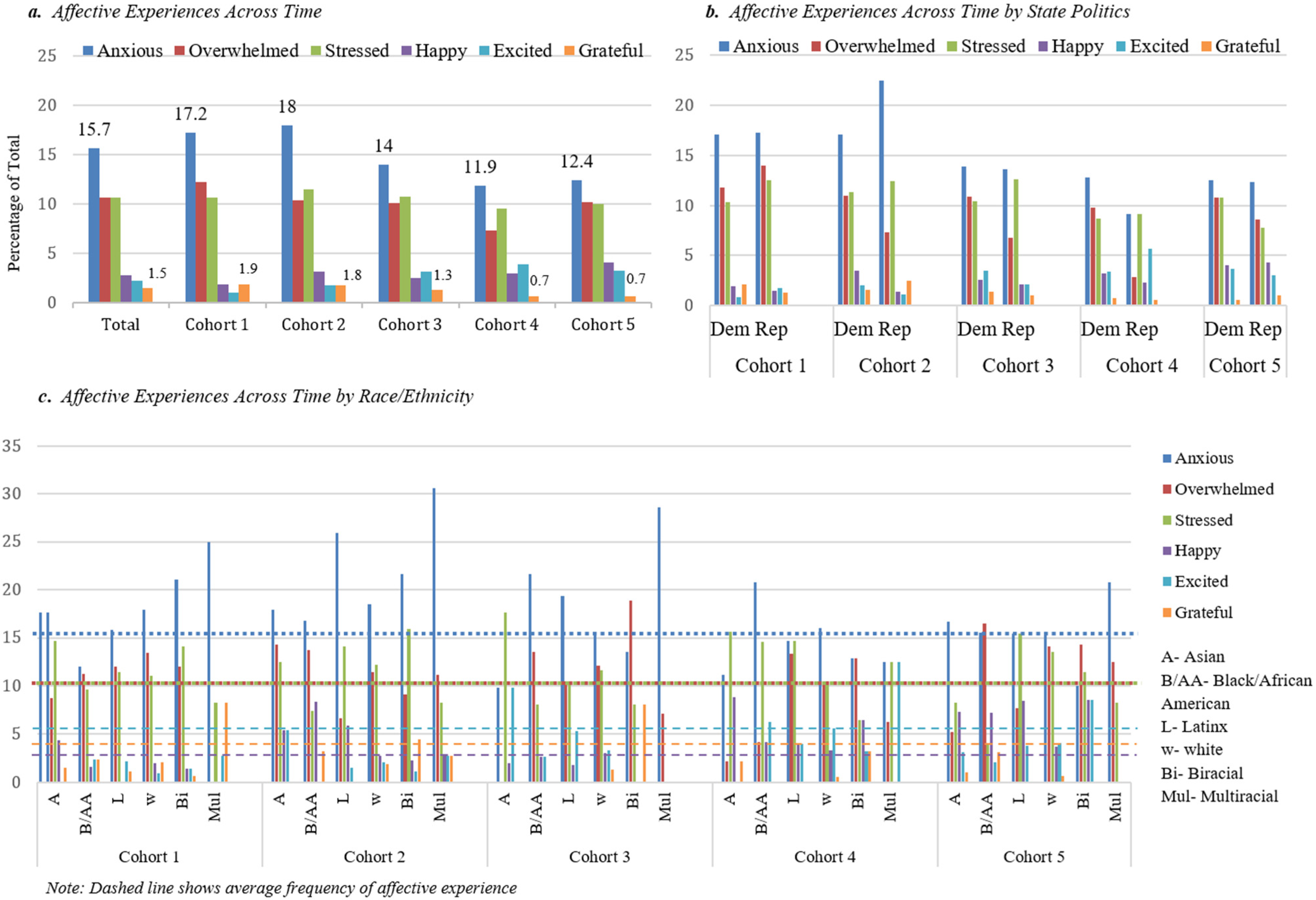

6.1.1. Primary Affective Experiences Research Question 1

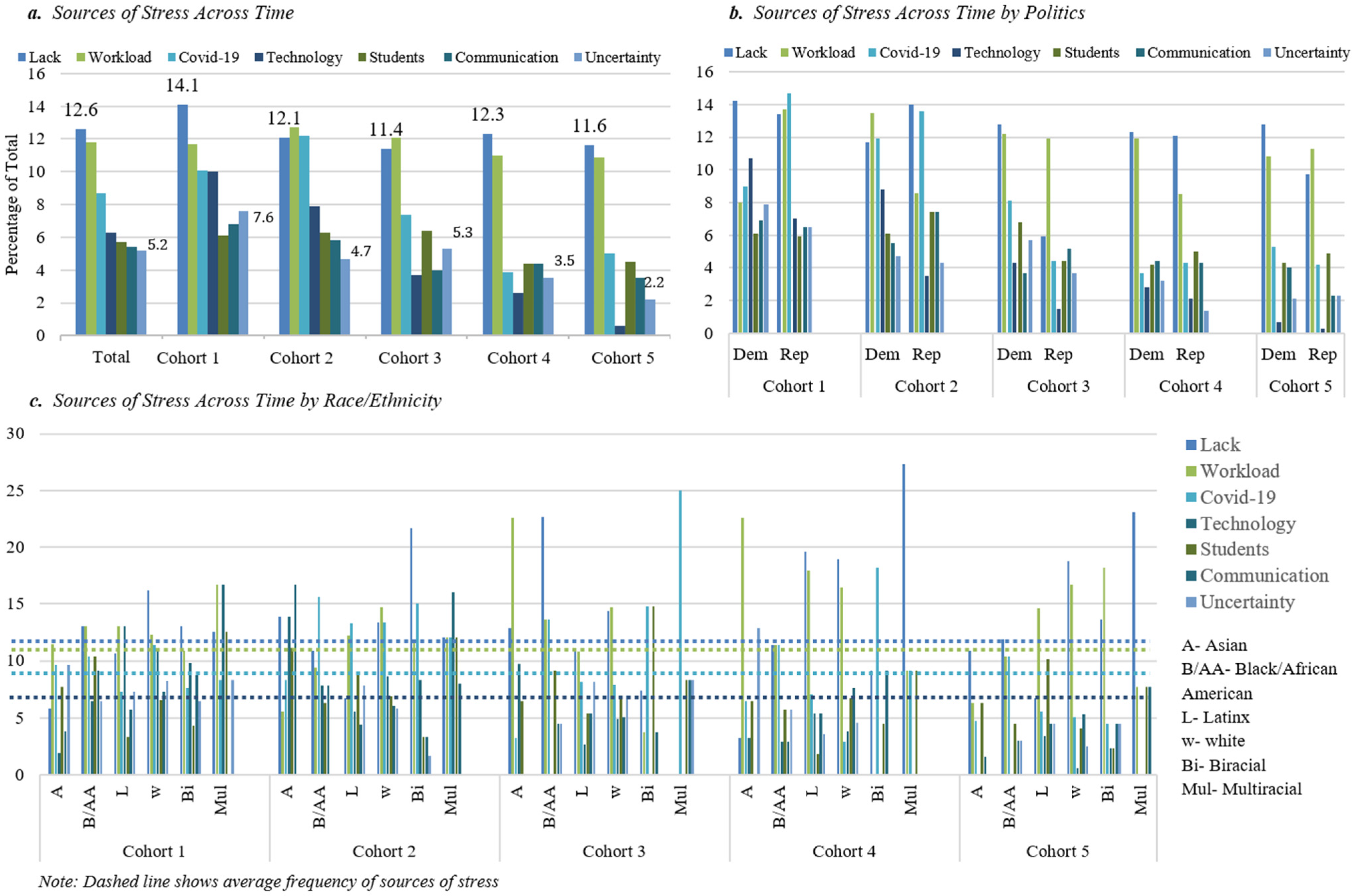

6.1.2. Primary Sources of Stress Research Question 2

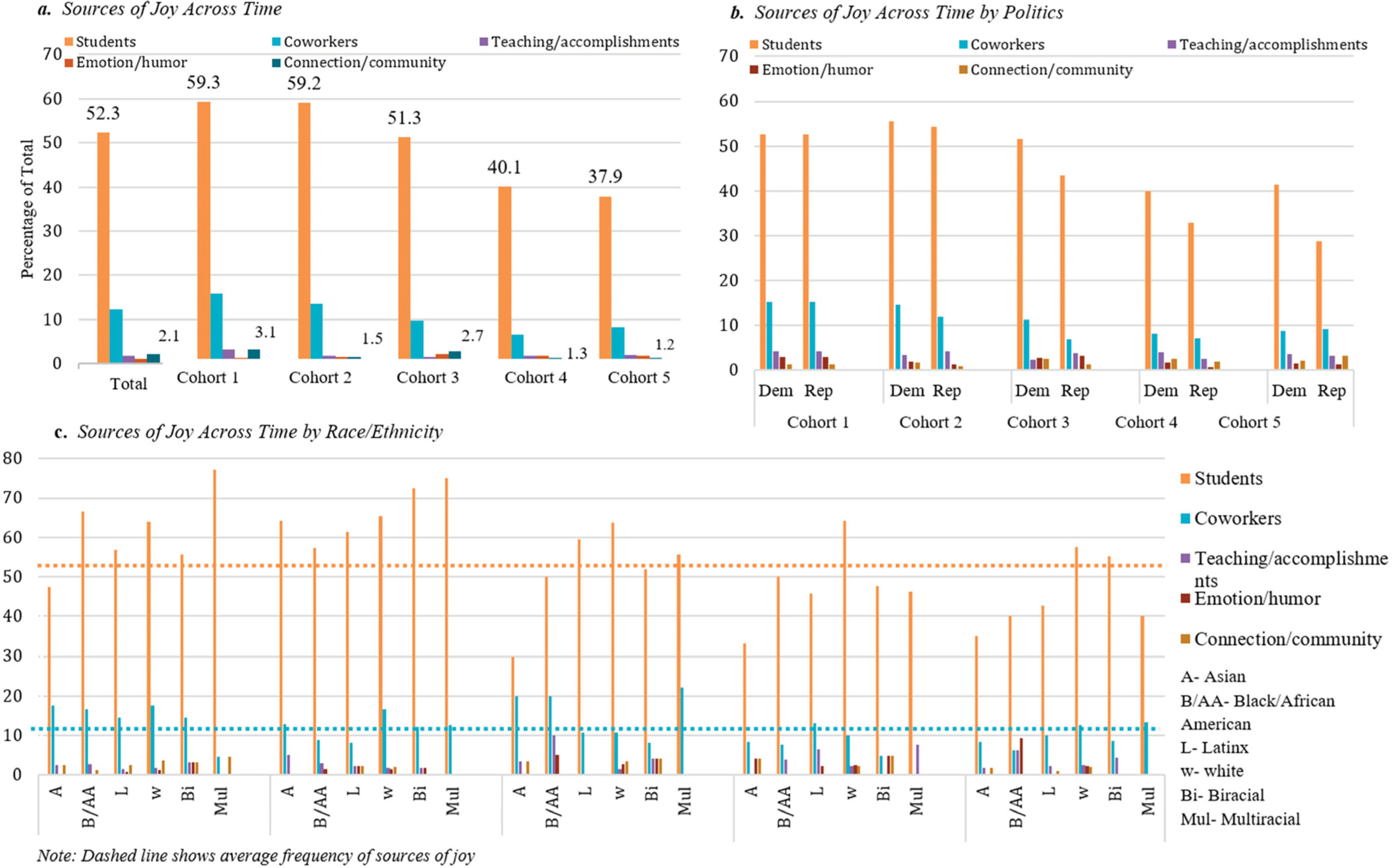

6.1.3. Primary Sources of Joy Research Question 3

6.1.4. SEL Supports Research Question 4

7. Discussion

7.1. Research Question 1: What Are School Personnel’s Feelings at Work?

7.2. Research Question 2a: The Primary Stressors of School Personnel

7.3. Research Question 2b: The Primary Joys of School Personnel

7.4. Research Question 3: Are Schools Supporting Student and School Personnel SEL?

7.5. Concluding Discussion

7.6. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hopman, J.; Clark, T. Finding a Way: What Crisis Reveals about Teachers’ Emotional Wellbeing and Its Importance for Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.; Woessmann, L. The legacy of COVID-19 in education. Econ. Policy 2023, 38, 609–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Liang, L.; Chutiyami, M.; Nicoll, S.; Khaerudin, T.; Ha, X.V. COVID-19 pandemic-related anxiety, stress, and depression among teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work 2022, 73, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, M.E.; Brewer, T.F.; Smith, M.S.; Stein, M.A.; Heymann, S.J. Lessons from United States school district policies and approaches to special education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmey, S.; Moss, G. Learning disruption or learning loss: Using evidence from unplanned closures to inform returning to school after COVID-19. Educ. Rev. 2023, 75, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadar, L.L.; Ergas, O.; Alpert, B.; Ariav, T. Rethinking teacher education in a VUCA world: Student teachers’ social-emotional competencies during the COVID-19 crisis. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S.; Morris, R.; Gunnell, D.; Ford, T.; Hollingworth, W.; Tilling, K.; Evans, R.; Bell, S.; Grey, J.; Brockman, R.; et al. Is teachers’ mental health and wellbeing associated with students’ mental health and wellbeing? J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 242, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elevating Teaching. U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/ (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Dunn, M.E. The Impact of a Social Emotional Learning Curriculum on the Social-Emotional Competence of Elementary-Age Students. Ph.D. Dissertations, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2295474355/abstract/A28BF68F238E45C0PQ/1 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Cipriano, C.; Strambler, M.J.; Naples, L.H.; Ha, C.; Kirk, M.; Wood, M.; Sehgal, K.; Zieher, A.K.; Eveleigh, A.; McCarthy, M.; et al. The state of evidence for social and emotional learning: A contemporary meta-analysis of universal school-based SEL interventions. Child Dev. 2023, 94, 1181–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.A.; Swennen, A. The COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on teacher education. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Coduto, K.D. Attitudinal and Emotional Reactions to the Insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. Am. Behav. Sci. 2024, 68, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konisky, D.M.; Nolette, P. The State of American Federalism, 2020–2021, Deepening Partisanship amid Tumultuous Times. Publius J. Fed. 2021, 51, 327–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberlander, J. Polarization, Partisanship, and Health in the United States. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 2024, 49, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, A.; Wolfe, R.L.; Steiner, E.D.; Doan, S.; Lawrence, R.A.; Berdie, L.; Greer, L.; Gittens, A.D.; Schwartz, H.L. Walking a Fine Line—Educators’ Views on Politicized Topics in Schooling: Findings from the State of the American Teacher and State of the American Principal Surveys. Research Report. RR-A1108-5; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.H.; Sondel, B.; Baggett, H.C. “I Don’t Want to Come Off as Pushing an Agenda”: How Contexts Shaped Teachers’ Pedagogy in the Days After the 2016, U.S. Presidential Election. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 56, 444–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, W.S.; Grafwallner, R.; Weisenfeld, G.G. Corona pandemic in the United States shapes new normal for young children and their families. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2021, 29, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshberg, M.J.; Davidson, R.J.; Goldberg, S.B. Educators Are Not Alright: Mental Health During COVID-19. Educ. Res. 2023, 52, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is SEL. CASEL District Resource Guide. Available online: https://drc.casel.org/what-is-sel/ (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- These Are the States with Mask Mandates during the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/these-are-the-states-with-mask-mandates (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Adolph, C.; Amano, K.; Bang-Jensen, B.; Fullman, N.; Wilkerson, J. Pandemic Politics: Timing State-Level Social Distancing Responses to COVID-19. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 2021, 46, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.A.; Greenberg, M.T. The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom Outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang-Rabrig, J.; Brüggemann, T.; Lorenz, R.; McElvany, N. Teachers’ occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of resources and demands. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 117, 103803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunzell, T.; Stokes, H.; Waters, L. Why do you work with struggling students?: Teacher perceptions of meaningful work in trauma-impacted classrooms. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. Online 2018, 43, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Kim, L.E. Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 105, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooms, A.A.; Mahatmya, D.; Johnson, E.T. The Retention of Educators of Color Amidst Institutionalized Racism. Educ. Policy 2021, 35, 180–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.Y.; Shin, M. A Meta-Analysis of Special Education Teachers’ Burnout. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020918297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower-Phipps, L. Discourses Governing Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual Teachers’ Disclosure of Sexual Orientation and Gender History. Issues Teach. Educ. 2017, 26, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Carver-Thomas, D.; Darling-Hammond, L. The trouble with teacher turnover: How teacher attrition affects students and schools. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2019, 27, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.A.; Bettini, E.; Brunsting, N. Special Education Teachers of Color Burnout, Working Conditions, and Recommendations for EBD Research. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2023, 31, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, P.; Zhai, X.; Dai, H.; Yang, Q. The Effect of Work Stress on Job Burnout Among Teachers: The Mediating Role of Self-efficacy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 122, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R.J. COVID-19 and Teachers’ Somatic Burden, Stress, and Emotional Exhaustion: Examining the Role of Principal Leadership and Workplace Buoyancy. AERA Open 2021, 7, 2332858420986187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevene, P.; De Stasio, S.; Fiorilli, C.; Buonomo, I.; Ragni, B.; Briegas, J.J.M.; Barni, D. Effect of Teachers’ Happiness on Teachers’ Health. The Mediating Role of Happiness at Work. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J.R.; Shoaf, G.; Huelsman, T.; McClannon, T. The Complexity of Teacher Job Satisfaction: Balancing Joys and Challenges. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2023, 33, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkowski, S.; Walker, K. Perspectives on Flourishing in Schools; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, S.S.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Roeser, R.W. Effects of teachers’ emotion regulation, burnout, and life satisfaction on student well-being. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.N.; Cipriano, C.; McCallops, K.; Cuccuini-Harmon, C.; Rivers, S.E. Examining the relationship between perceptions of teaching self-efficacy, school support and teacher and paraeducator burnout in a residential school setting. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2018, 23, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Guetterman, T.C. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Littlecott, H.J.; Moore, G.F.; Murphy, S.M. Student health and well-being in secondary schools: The role of school support staff alongside teaching staff. Pastor. Care Educ. 2018, 36, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.; Whitear, B.A.; Brown, S. A review of substance use education in fifty secondary schools in South Wales. Health Educ. J. 2001, 60, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieher, A.K.; Cipriano, C.; Meyer, J.L.; Strambler, M.J. Educators’ implementation and use of social and emotional learning early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. Supporting Connecticut Educators with SEL During Times of Uncertainty and Stress: Fall 2020 Findings; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pressley, T.; Ha, C. Teaching during a Pandemic: United States Teachers’ Self-Efficacy During COVID-19. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 106, 103465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.L.; Gaines, R.E.; Mosley, K.C. Effects of Autonomy Support and Emotion Regulation on Teacher Burnout in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 846290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.; Russell, S.; Saulle, R.; Croker, H.; Stansfield, C.; Packer, J.; Nicholls, D.; Goddings, A.-L.; Bonell, C.; Hudson, L.; et al. School Closures During Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-being Among Children and Adolescents during the First COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacher-Hicks, A.; Chi, O.L.; Orellana, A. Two Years Later: How COVID-19 Has Shaped the Teacher Workforce. Educ. Res. Wash. DC 1972 2023, 52, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuade, L. Factors affecting secondary teacher wellbeing in England: Self-perceptions, policy and politics. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2024, 50, 1367–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. Challenges and Opportunities for Teaching Students with Disabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Multidiscip. Perspect. High. Educ. 2020, 5, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SITE—Tweeting about Teachers and COVID-19: An Emotion and Sentiment Analysis Approach. Available online: https://academicexperts.org/conf/site/2022/papers/60965/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Hartney, M.T.; Finger, L.K. Politics, Markets, and Pandemics: Public Education’s Response to COVID-19. Perspect. Polit. 2022, 20, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosland, T.; Roberts, L. Leading with/in Emotion States: The Criticality of Political Subjects and Policy Debates in Educational Leadership on Emotions. Policy Futur. Educ. 2021, 19, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reflecting on Social Emotional Learning: ACritical Perspective on Trends in the United States—Diane, M. Hoffman, 2009. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.3102/0034654308325184 (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Dusenbury, L.; Yoder, N.; Dermody, C.; Weissberg, R. An examination of frameworks for social and emotional learning (SEL) reflected in state K-12 learning standards. Meas. SEL Using Data Inspire Pract. 2019, 3, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

| Total | Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | Cohort 4 | Cohort 5 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 8052 | 2903 | 1990 | 925 | 737 | 1397 | ||||||

| Individual Characteristics | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Age | 43.2 | 12 | 44 | 11.27 | 42.5 | 11.5 | 43.1 | 11.3 | 42.3 | 11.7 | 41.8 | 12.0 |

| Years of Experience | 12.4 | 10 | 14.1 | 10 | 13.1 | 9.7 | 12.0 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 9.7 |

| Race and Ethnicity | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 44 | 0.5 | 11 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.3 | 8 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.5 | 16 | 1.6 |

| Asian | 316 | 3.9 | 68 | 2.3 | 56 | 2.8 | 51 | 5.5 | 45 | 6.1 | 96 | 6.4 |

| Black or African American | 402 | 5.0 | 125 | 4.3 | 95 | 4.8 | 37 | 4.0 | 48 | 6.5 | 97 | 6.5 |

| Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish | 581 | 7.2 | 184 | 6.3 | 135 | 6.8 | 57 | 6.2 | 75 | 10.2 | 130 | 8.7 |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 49 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.5 | 12 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.5 | 6 | 0.8 | 12 | 0.8 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 15 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.3 |

| White | 5249 | 65.2 | 2167 | 74.6 | 1410 | 70.9 | 604 | 65.3 | 337 | 45.7 | 731 | 48.8 |

| Biracial | 368 | 4.6 | 142 | 4.9 | 88 | 4.4 | 37 | 4.0 | 31 | 4.2 | 70 | 4.7 |

| Multiracial (more than 3) | 126 | 1.6 | 36 | 1.2 | 36 | 1.8 | 14 | 1.5 | 16 | 2.2 | 24 | 1.6 |

| Unspecified | 902 | 11.2 | 132 | 4.5 | 138 | 6.9 | 112 | 12.1 | 171 | 23.2 | 317 | 21.2 |

| Gender | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Female | 6376 | 79.2 | 2470 | 85.1 | 1658 | 83.3 | 726 | 78.5 | 501 | 68.0 | 1021 | 68.2 |

| Male | 900 | 11.2 | 310 | 10.7 | 205 | 10.3 | 105 | 11.4 | 83 | 11.3 | 194 | 13.0 |

| Non-binary | 18 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Mahu | 1 | <0.1 | 1 | <0.1 | ||||||||

| Genderqueer | 1 | <0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | ||||||||

| Transgender Male | 3 | <0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Unspecified | 757 | 9.4 | 110 | 3.8 | 121 | 6.1 | 93 | 10.1 | 150 | 20.4 | 227 | 18.5 |

| 2020 State Presidential Election Results | n | % | ||||||||||

| Democratic | 6390 | 79.4 | 2361 | 81.3 | 1634 | 82.1 | 734 | 79.4 | 561 | 76.1 | 1100 | 73.5 |

| Republican | 1662 | 20.6 | 542 | 18.7 | 356 | 17.9 | 191 | 20.6 | 176 | 23.9 | 397 | 26.5 |

| M(SD) | df | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 12/01/20-01/05/21 Survey Launch | Edu SEL | 3.18 (1.18) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 10 | 3.24 | <0.001 *** | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 0.42 | 0.515 | ||

| Support for Stu SEL | 1.96 (0.69) | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 10 | 1.36 | 0.191 | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 11.07 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Cohort 2 01/06/21–02/28/21 U. S. Capital Insurrection | Edu SEL | 3.18 (1.24) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 10 | 1.01 | 0.428 | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 2.31 | 0.130 | ||

| Support for Stu SEL | 1.93 (0.75) | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 10 | 2.02 | 0.028 | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 21.35 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Cohort 3 03/01/21–05/31/21 Vaccine Rollout | Edu SEL | 3.05 (1.27) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 9 | 1.87 | 0.054 † | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 2.37 | 0.124 | ||

| Support for Stu SEL | 1.81 (0.77) | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 9 | 1.18 | 0.306 | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 12.24 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Cohort 4 06/01/21–08/14/21 Summer | Edu SEL | 3.01 (1.20) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 10 | 0.56 | 0.844 | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 0.97 | 0.323 | ||

| Support for Stu SEL | 1.78 (0.82) | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 10 | 0.87 | 0.559 | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 3.81 | 0.052 | ||

| Cohort 5 08/15/21–12/01/21 Returning to School in the Fall | Edu SEL | 2.82 (1.32) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 10 | 1.10 | 0.362 | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 3.67 | 0.056 † | ||

| Support for Stu SEL | 1.79 (0.81) | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 10 | 1.01 | 0.436 | ||

| State Politics | 1 | 17.28 | <0.001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wood, M.; Ha, C.; Brackett, M.; Cipriano, C. Affective Experiences of U.S. School Personnel in the Sociopolitical Context of 2021: Reflecting on the Past to Shape the Future. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101093

Wood M, Ha C, Brackett M, Cipriano C. Affective Experiences of U.S. School Personnel in the Sociopolitical Context of 2021: Reflecting on the Past to Shape the Future. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(10):1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101093

Chicago/Turabian StyleWood, Miranda, Cheyeon Ha, Marc Brackett, and Christina Cipriano. 2024. "Affective Experiences of U.S. School Personnel in the Sociopolitical Context of 2021: Reflecting on the Past to Shape the Future" Education Sciences 14, no. 10: 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101093

APA StyleWood, M., Ha, C., Brackett, M., & Cipriano, C. (2024). Affective Experiences of U.S. School Personnel in the Sociopolitical Context of 2021: Reflecting on the Past to Shape the Future. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101093