Abstract

Social goals are increasingly seen as motivational factors for youth sports participation and can strongly motivate participation and engagement, not only in structured sports contexts but also in physical education (PE), given the opportunities for social interaction with peers and the presence of skills like communication, cooperation, and competition within groups. The Social Motivational Orientations in Sport Scale (SMOSS) measures three types of social goals in sports participation: affiliation, status, and recognition. The current study aimed to adapt and validate the SMOSS for the Portuguese context, using a sample of 460 PE students (14–19 years old, 58.9% female). The confirmatory factor analysis results supported the three-factor model (affiliation, recognition, and status), after excluding two items. This adapted 13-item SMOSS demonstrated invariance across genders and showed good internal consistency across its three dimensions. It also exhibited convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. These findings indicate that the Portuguese version of the SMOSS is a valid and reliable instrument. It is now well suited for use by schools, teachers, and psychologists to effectively assess PE students’ social goals. Additionally, the SMOSS can assist in evaluating intervention programs aimed at enhancing students’ social motivation, thus contributing to more effective educational and developmental strategies in PE settings.

1. Introduction

Human motivation is a multifaceted phenomenon influenced by a complex interplay of internal and external factors, with social factors playing a significant role [1]. However, for many years, research on motivation for sports participation among both youth and adults has undervalued the social dimension. The Achievement Motivation Theory (e.g., [2,3]) has made an undeniable contribution to understanding the psychological processes underlying motivation, particularly regarding the social dimension. It explores how different needs—the need for achievement, the need for power, and the need for social relationships and acceptance—impact an individual’s motivation across various contexts. Specifically, Maehr and Nicholls proposed social approval orientation as one of the social goals within the three universal goals of motivation. This social approval perspective on motivation began to attract research attention (e.g., [4,5,6]), providing evidence of its influence in the sports context. Researchers have also found that, in addition to social approval, multiple social goals play a crucial role in determining youth motivation to participate in sports and physical activities, whether through group affiliation, the development of friendships, or the pursuit of status and social recognition [6,7,8]. However, a major limitation was the lack of a clear understanding of how social goal orientations and social connections contribute to youth sports participation. In other words, there was a need for a consistent conceptualization of the multiple social goals, as well as a valid and rseliable measurement tool [1,9].

Despite an initial attempt to develop a measurement instrument, the Achievement Orientation Questionnaire (AOQ) [10], which included three achievement orientations (i.e., ability, mastery, and social approval), the inconsistent research findings regarding its psychometric properties—particularly its factor structure—highlighted the need for a new instrument. To address this need, Allen [1] proposed a conceptually based approach to examining social motivation in sports, arguing that the need for social connections drives goal-directed behavior and that achievement in sports can be understood in social terms, as it offers opportunities to pursue social goals.

Based on previous research in sport and education, Allen initially proposed two social motivational orientations: affiliation, which focuses on developing reciprocal relationships and positive social experiences, and social validation, which aims at gaining social status and recognition through sport involvement.

However, an exploratory factor analysis of data from a sample of high school students yielded a three-factor structure, indicating the presence of three types of social goal orientations, an affiliation orientation and two variations of social goal orientation: social status among peers, and social recognition related to one’s ability [1,9]. In line with these findings, the Social Motivational Orientations in Sport Scale (SMOSS) [1] was introduced as an alternative measurement tool to traditional approaches centered on physical ability, competence, or mastery goal orientations.

According to this tri-factorial framework, the affiliation motivation orientation emphasizes developing and maintaining satisfying relationships. Items in this subscale relate to teamwork in the sporting environment and the roles and responsibilities of participants in team-oriented games (e.g., “I make some good friends on the team”, “Spending time with the other players is enjoyable”) [1,9]. The second orientation, recognition, reflects motivation derived from the opportunities that sports provide for receiving social recognition or positive feedback related to one’s involvement in sport activities, abilities, or performance (e.g., “Others are impressed by my sporting ability”, “Other kids think I am really good at sports”) [1,9]. Finally, the status orientation highlights the motivation to engage in sport due to peer popularity and the social position that participation in sport can offer (e.g., “I am the center of attention”, “I am part of the ‘in’ crowd”) [1,9].

Social factors, affiliation, status, and recognition can strongly motivate participation and engagement, not only in structured sports contexts [1,9] but also in PE. The PE classroom environment provides students greater freedom and opportunities for social interaction with peers, particularly compared to other subjects in the school curriculum [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Moreover, PE curriculum content emphasizes communication, cooperation, and competition within pairs, small groups, or teams. Consequently, social interactions occur both within and across peer groups, as well as with teachers. Additionally, the social aspiration to be athletic and physically capable heightens the motivational significance of social opportunities in PE, especially during adolescence when social acceptance holds considerable importance [17]. Given these factors, PE presents itself as a social milieu conducive to a diverse range of social opportunities and, thus, is well suited for examining motivation from a social goal perspective [11,12,13,14,15,16].

Although the SMOSS was introduced two decades ago, it remains the only instrument for measuring social motivational orientations in sports. While some studies have adapted the SMOSS for use in the PE setting [13,14,15], to the best of our knowledge, only two studies have been devoted to psychometric evaluation of the SMOSS across diverse samples, specifically adolescents within the physical activity context [16,18].

Although Allen’s social motivation theory initially evolved within sports contexts, traditional PE settings provide a comparable environment for applying this framework due to the inclusion of sport-related content in PE curricula and the ample opportunities for social interactions. Despite some studies that adapted the SMOSS for the PE context [13,14,15], there has yet to be a validated translation of this instrument for the Portuguese population. Additionally, there is no validation, to date, of the SMOSS in any other language.

Hence, the primary aim of the present study was to validate a Portuguese version of the SMOSS specifically for Portuguese PE students. This is particularly relevant as a Portuguese version of the SMOSS has the potential to enhance our understanding and assessment of the social factors influencing Portuguese youth participation in PE classes, as well as facilitate the identification and development of intervention programs addressing difficulties in this area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study sample comprised 460 Portuguese students from seven public schools in the northwest of Portugal, selected for convenience. Their ages ranged from 14 to 19 years (M = 16.44, SD = 1.078), and 58.9% were female. The students were enrolled in various school years, including 9th grade (n = 22), 10th grade (n = 193), 11th grade (n = 71), and 12th grade (n = 174), and participated in PE classes. At the time of the study, 26.5% of the participants (n = 122) were athletes. Each class had two PE lessons per week (one lesson of 45 min and another of 90 min).

During this study, an expert group of translators and academics was assembled to supervise the translation, adaptation, and content validation of the Portuguese SMOSS. The group included three translators, an external bilingual speaker fluent in both Portuguese and English and three academics with PhDs in Physical Education/Sport Psychology.

The a priori sample size calculator for Structural Equation Analysis [19] was used to establish the minimum sample size required for the study. Given a predicted effect size of 0.30, a desired statistical power of 0.95, a probability level of 0.05, three latent variables, and eight observed variables, the recommended minimum sample was 184 participants. This requirement was met in the current study.

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Translation and Adaptation Procedures

With permission obtained via email from the author of the questionnaire, Professor Justine Allen, the process of translation was carried out using the forward–backward translation technique [20]. This process involved three members of the research group and an external bilingual speaker fluent in both Portuguese and English. First, two native Portuguese-speaking educational researchers independently translated the items into Portuguese, and these translations were subsequently reviewed, revised, and compared in collaboration. The resulting translated version of the questionnaire was then assessed by a Portuguese-speaking expert in educational research. Back-translation of the questionnaire was then performed by a professional bilingual translator who was not involved in the initial forward translation. Finally, a comparison of the back-translated version and the original questionnaire was performed by individuals proficient in both Portuguese and English.

The content validity of the Portuguese version of the SMOSS was assessed by a panel of experts [21] to ensure the quality and suitability of the items for the PE context.

To evaluate face validity, a pilot study was conducted with the Portuguese version of the SMOSS to examine the questionnaire’s structure and the functionality of data collection procedures and to identify potential issues with item wording. In this pilot study, a total of 50 high school students completed the survey. Feedback from these participants led to minor modifications, but no changes were made to the structure of the survey. All participants were able to complete the questionnaire in approximately 5 min.

2.2.2. Data Collection Procedures

The psychometric study was conducted from January to June 2022 and involved the translation and adaptation of the SMOSS from English into Portuguese, as well as the psychometric validation of the Portuguese version of the questionnaire.

Prior to starting data collection, the study was reviewed and received approval from the University Ethics Board (Reference: CEFADE 38_2022), ensuring it was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All data were fully encrypted to safeguard the privacy of the participants.

School principals and physical education teachers were informed about the study’s objectives and methods prior to being invited to participate. After obtaining necessary authorizations from the schools, informed written consent was obtained from the participants and, if they were under 18 years of age, from their parents. This consent process included an explanation of the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, the option to withdraw from the study at any time, and a guarantee of anonymity and the confidentiality of their responses. No incentives or rewards were offered to participants for their involvement. All parents and participants, including those under 18, signed consent forms. Participants completed the questionnaires in their classrooms, with the presence of a researcher who was trained to explain the study and facilitate the completion of questionnaires. On average, the administration process took about 5 min.

2.2.3. Measures

- Social motivational orientations.

The Social Motivational Orientations in Sport Scale (SMOSS) [1] was developed to assess different social goals in sports, namely affiliation goals, recognition goals, and status goals. The affiliation goals subscale of the SMOSS consists of seven items (e.g., “I make some good friends in class”), the social recognition goals subscale comprises four items (e.g., “Others tell me I have performed well”), and the social status subscale consists of four items (e.g., “I belong to the popular group in physical education class”).

The 15 items of the scale were rated by participants using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Various studies have demonstrated the reliability and validity of the SMOSS in the high school context [9,13]. These studies reported satisfactory levels of internal consistency, with values ranging from acceptable (α = 0.75) to excellent (α = 0.95).

- Social cohesion.

To examine the concurrent validity of the SMOSS, we used baseline scores from the 8-item social cohesion subscale of the Youth Sport Environment Questionnaire YSEQ (YSEQ; [22]). Social cohesion, originally described as the “total field of forces which act on members to remain in the group” [23], is a central explanatory construct for understanding key social group processes and orientations [24]. Since social orientations reflect the overall level of motivation within a group to maintain social relationships and the members’ willingness to preserve unity over time [25], group cohesion and social orientations (i.e., affiliation, status, and recognition) both represent emergent states in a group that are influenced by environmental factors such as motivational climate [26] and, therefore, would be expected to be positively correlated.

The social cohesion subscale of the YSEQ is designed to evaluate students’ interpersonal involvement in their PE classes and the degree of integration among group members concerning friendship and feelings of closeness (example item: “I spend time with my classmates”). The YSEQ employs a 9-point Likert-type scale, with response options ranging from 1 (Totally Disagree) to 9 (Totally Agree), where higher scores indicate stronger perceptions of social cohesion. Validation studies for this scale have consistently revealed satisfactory psychometric characteristics [27,28].

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using RStudio (version 2022.10.31) for Windows and IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows (Armonk, NY, USA) version 29.0. JASP (version 0.19.0) was used to generate the images presented.

To assess the structural validity of the Portuguese SMOSS, we performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the lavaan package [29] in RStudio.

Since an a priori model of the latent construct has been established, it was unnecessary to conduct an exploratory factor analysis [30,31,32]. For the CFA, we examined outliers by considering Mahalanobis squared distance (D2). Univariate data normality was verified through skewness and kurtosis tests, while multivariate distribution was assessed by Mardia’s coefficient [31]. Given the ordinal nature of the data and lack of multivariate normality, we employed the diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator [33,34]. Model fit was evaluated using several recommended goodness-of-fit indexes: the chi-square (χ2) statistical test, the ratio of χ2 to its degrees of freedom (χ2/df), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the normed fit index (NFI), the parsimony normed fit index (PNFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Values of CFI, TLI, and NFI ≥ 0.90 indicated a good and adequate model fit to the data [32]. Additionally, a value of χ2/df < 5 and an RMSEA < 0.08 were considered indicative of an acceptable fit to the data [31,32,35].

The internal consistency (reliability) of the instrument was assessed using Hancock’s H [36,37], where an H value > 0.9 was preferred [38].

Convergent validity was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE), with an acceptable threshold of ≥0.5. Discriminant validity was confirmed when the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio of correlation (HTMT) (HTMT; [39]) was found to be less than 0.85 [31,40].

To test for factorial invariance across gender, a multi-group CFA (MGCFA) approach was used. This analysis tests three levels of invariance: configural (similar structure across groups), metric (loading weights identical across groups), and scalar (intercepts identical across groups) [41]. Factorial invariance was accepted when the ΔCFI ≤ −0.01 and ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015 [42,43]. Finally, to assess concurrent validity, we conducted bivariate correlation analyses involving the YSEQ social cohesion subscale. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

Descriptive analysis revealed that there were no missing data in the dataset. The overall internal reliability index for the translated SMOSS was 0.91, and the reliability for each subscale was good, ranging from ω = 0.87 (recognition) to ω = 0.89 (status). Analysis of skewness and kurtosis values suggested that the data exhibited approximate univariate normality. The absolute values of skewness fell below 3 (ranging from −1.602 to 0.742), and the kurtosis values were below 7 (ranging from −1.472 to 6.498) [31]. However, the data violated the assumption of multivariate normality, as indicated by the notably high Mardia’s coefficient of 58.207. Consequently, we employed a DWLS estimator, which is less dependent on the normality assumption and better suited to the categorical nature of measurement (i.e., ordinal data) [33,34,44].

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The first-order three-factor model of the Portuguese SMOSS did not present an adequate fit to the data according to all indices [χ2 = 494.10, p < 0.001; χ2/df = 6.67, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, NFI = 0.95, PNFI = 0.80, RMSEA = 0.11]. In particular, the χ2/df and RMSEA values exceeded the recommended thresholds [32]. An examination of modification indices suggested that model fit could be improved by adhering to the approach proposed by Chartrand, Robbins, Morril, and Boggs [45] to create “pure measures of each factor” (p = 0.495) by allowing items to load on only one factor. Because the modification indices suggested that items 14 and 15 were related to different factors, they were subsequently removed from the model.

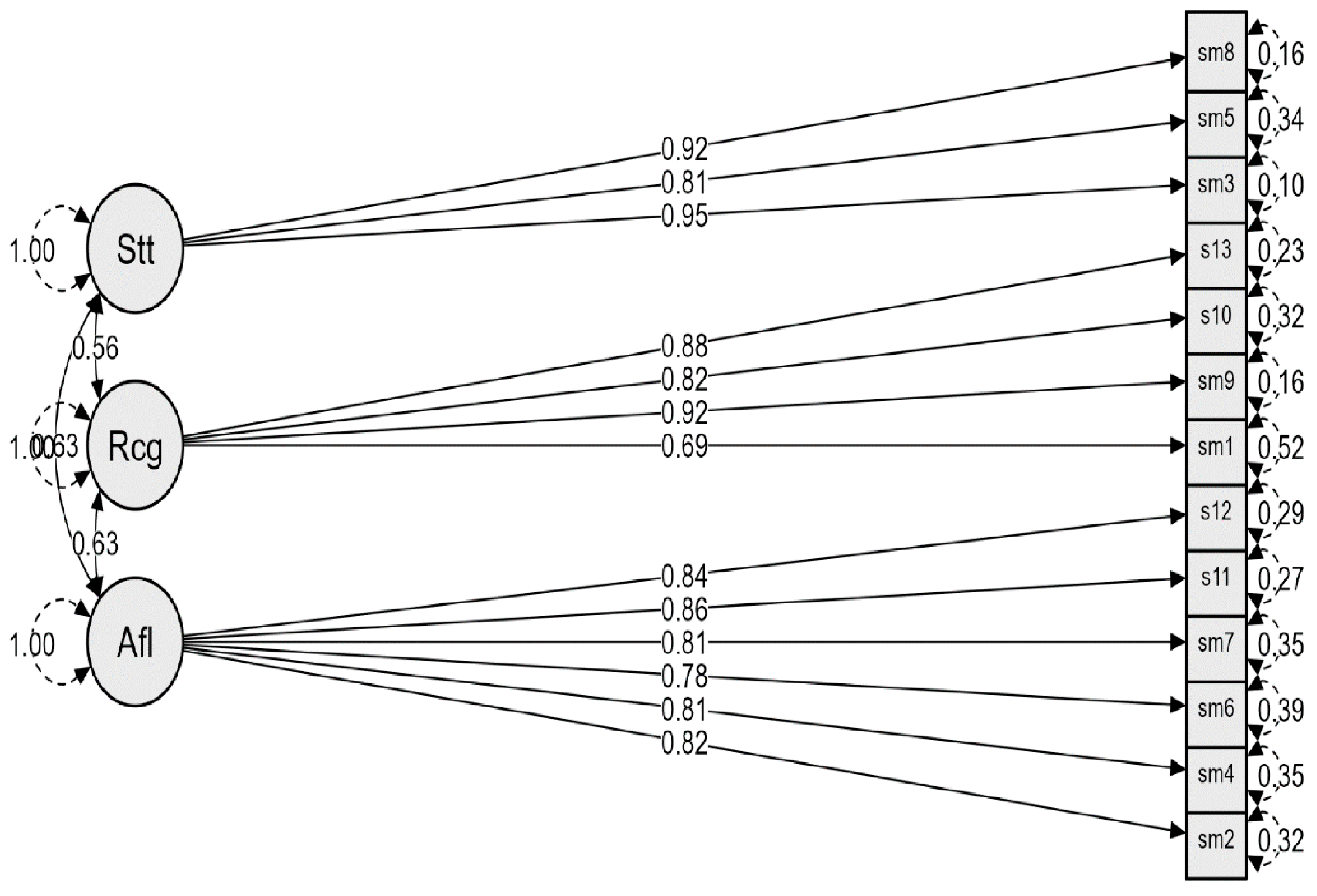

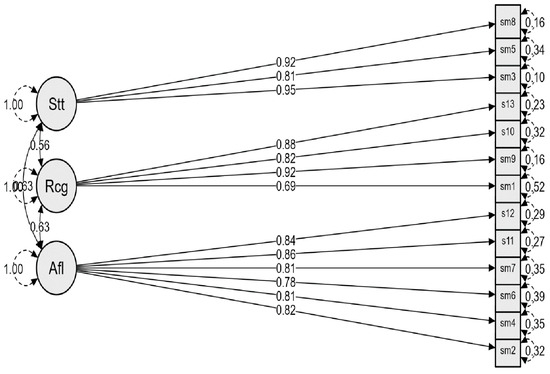

After these item exclusions, all goodness-of-fit indices demonstrated the model had a satisfactory fit to the data, [χ2 = 271.96, p < 0.001; χ2/df = 4.38, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97, NFI = 0.97, PNFI = 0.79, RMSEA = 0.08]. Therefore, the final model comprised 13 items: six items related to social affiliation goals, four items associated with social recognition goals, and three items linked to social status goals (Figure 1). The standardized factor loadings for these items ranged from 0.69 to 0.95 (all p < 0.001) (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Re-specified model of the Portuguese version of SMOSS.

Table 1.

Portuguese version of SMOSS—factor loadings, Z-values, Hancock’s H (H), and average variance extracted (AVE).

Hancock’s H values ranged from 0.92 (social recognition) to 0.94 (social status), indicating that the factor structure had strong internal consistency [36,37]. Additionally, evidence supporting convergent validity was obtained, as the AVE values ranged from 0.67 (social affiliation) to 0.80 (social status), all of which exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50 [46] (see Table 1).

To test discriminant validity, we analyzed the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio of correlation [39]. As shown in Table 2, all constructs were found to demonstrate discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity for the Portuguese version of SMOSS—HTMT results.

A multiple-group CFA was conducted to assess the measurement invariance between girls and boys. As shown in Table 3, the fit indices for the baseline model supported the hypothesis of configural measurement invariance [χ2 = 301.255, p < 0.001; χ2/df = 2.429, CFI = 0.947, RMSEA = 0.056], indicating that the three-factor structure was consistent in both groups. Changes to CFI and RMSEA with the addition of model constraints supported metric invariance but not scalar invariance (Table 3). The analysis of confidence intervals reveals that the starting points differ between the groups, thereby limiting the validity of comparing mean scores between boys and girls.

Table 3.

Measurement invariance across gender.

Concurrent validity analysis was conducted using the three factors of the SMOSS, referred to as latent factor 1 (6 items), latent factor 2 (4 items), and latent factor 3 (3 items) respectively. Three bivariate correlations were computed to assess the concurrent validity of the SMOSS: (1) between latent variable 1 and the YSEQ social cohesion subscale, (2) between latent variable 2 and the YSEQ social cohesion subscale, and (3) between latent variable 3 and the YSEQ social cohesion subscale. Analyses yielded moderate positive correlations (r = 0.507, 0.407, 0.397, respectively), indicating acceptable concurrent validity between measures.

4. Discussion

The primary goal of the present study was to translate and validate the SMOSS [1] for use in Portuguese PE students. Overall, the study indicated that the Portuguese version of the SMOSS had adequate psychometric properties, with analyses supporting construct, convergent and divergent validity, internal consistency reliability, and measurement invariance across genders. Significant correlations between the three SMOSS dimensions also supported construct validity, consistent with other study results [16,18].

Our study successfully replicated the three-factor model proposed by [1], with our sample comprising adolescents in the context of PE. The factorial structure observed in our study, which focused on the PE context, was consistent with previous studies that examined youth motivations in after-school sports and physical activity programs, suggesting that these social motivational orientations are applicable across diverse contexts [1,9,16]. In alignment with the findings of our study, Deng, Roberts, Zhang, Taylor, Fairchild and Zarrett [16] investigated social goals in an adolescent sample, extending the scope to physical activity more broadly. Their study confirmed the three-factor structure and demonstrated that social goals for physical activity in early adolescence mirror those found in late adolescence and adulthood, as found in Allen’s studies. Although a two-factor model was also considered in their analysis, the data ultimately favored the three-factor structure as a better fit. In contrast, Roberts [18], when examining the validity of the SMOSS in a similar sample, identified only two factors (affiliation and recognition) rather than the three originally proposed, suggesting that the scale’s factor structure may vary depending on the characteristics of the sample.

Nevertheless, it was noteworthy that we had to exclude two items from the original 15-item scale (items 14 and 15) to obtain a satisfactory model fit in CFA. This is because both items had moderate correlations with items associated with other factors, namely, social recognition, thus suggesting these items did not provide useful discrimination between factors. This finding is consistent with Allen’s [9] validation study in high school students, which demonstrated a statistically appropriate fit after removing item 14 from the social status sub-scale (“I am one of the more popular players”). The correlation found between this item and item 9 from the social recognition sub-scale (“Other kids think I’m really good at sport”) did not provide useful discrimination between the social status and social recognition factors. From this result emerges a possible relationship between recognizing someone’s ability and a student’s individual popularity; however, that is different from being part of the popular group. Although being good at sports can increase popularity among peers, students can also gain popularity as players by being good at sports, regardless of whether they belong to the popular group or not. In fact, as Allen [47] suggested, modifications to the SMOSS are likely necessary to fully capture social goals within the specific context, a point that seems to remain relevant today.

Weak factorial gender invariance (configural and metric) was supported, demonstrating that boys and girls have a similar understanding of the scale’s items. Given the presence of metric invariance, it is possible to compare the relationships between the latent construct and the scale items across boys and girls. However, the absence of scalar invariance restricts the comparison of mean scores between the groups, as boys and girls may respond to the items differently in absolute terms. The analysis of confidence intervals further confirms that the starting points differ between the groups. In summary, while boys and girls interpret the items similarly concerning the measured construct, differences in their scores cannot be interpreted as genuine differences in the latent construct due to the lack of scalar invariance. It should be emphasized that the present study is the first to evaluate the invariance of the SMOSS. In previous psychometric validations, the original study that introduced the instrument, developed by Allen [1], used a sample of only girls and did not examine any form of invariance. In a subsequent study in 2005, the same author, using a sample with female and male gender participants, only evaluated the scale’s construct validity (factorial, convergent, and divergent). More recently, Roberts [18] and Deng et al. [16], both working with mixed samples, focused their research on assessing the factor structure and criterion validity (concurrent and predictive) of the SMOSS.

Finally, the concurrent validity of SMOSS was demonstrated through significant positive correlations between its factors and a measure of social cohesion. However, it is important to note that the inter-correlations between the scale’s factors were moderate (ranging from 0.40 to 0.51), providing only limited evidence of validity [48,49]. These findings are consistent with results found by Deng, Roberts, Zhang, Taylor, Fairchild and Zarrett [16], which have identified significant yet moderate relationships among the three original subscales and feelings of relatedness and social motivation to engage in PE. In the analysis of concurrent validity, several studies have reported acceptable concurrent validity between measures, with results of a similar magnitude to those observed in the present study [50,51]. One of the key challenges in testing concurrent validity for questionnaire-based measures is the lack of widely accepted gold standards. In fact, some of the so-called gold standards may themselves fail to provide entirely accurate estimates of the phenomena being measured [52].

Limitations and Future Directions

As with all studies, it is important to acknowledge limitations. In this study, one such limitation relates to the sampling methods and Portugal’s unique cultural context. First, though the sample was appropriate for its purpose, its specific demographic characteristics may mean it was not fully representative of the Portuguese population. For example, our participants were recruited exclusively from the north of mainland Portugal, so future studies should consider investigating the properties of the scale with Portuguese students from different regions in order to confirm stability, specifically with confirmatory factor analysis. Second, although our sample meets several recommendations for conducting a CFA, we acknowledge the prevailing scientific consensus that a larger sample size is preferable and more likely to yield generalizable and replicable results [53].

As the first validated instrument for Portuguese PE students, additional research is necessary to reinforce its validity, reliability, and overall effectiveness. Although our study demonstrates acceptable values for concurrent validity, the evidence remains somewhat limited due to the moderate strength of the observed correlations. Therefore, further testing of criterion validity, particularly through the establishment of predictive validity, is essential for evaluating the overall quality and robustness of the scale. In addition to conducting further studies in the Portuguese language, we also emphasize the importance of validating the instrument in other linguistic contexts.

Future studies could also analyze the invariance between various age groups (children, adolescents, or adults) to test the ability of the scale to be applicable throughout life.

Therefore, future studies should continue to adapt the SMOSS culturally and linguistically for other contexts and assess its psychometric properties, thereby broadening its applicability and enhancing the assessment of social goals in youth sports participation.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of this study provide preliminary support for the structural validity and reliability of the Portuguese version of the SMOSS, demonstrating its suitability as a comprehensive and valid instrument for use among Portuguese youth aged 14 to 19. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to offer psychometric evidence for an instrument that measures three types of social goals in sports participation (affiliation, status, and recognition) in a language other than English, specifically within the Portuguese school context.

6. Practical Implications

The validation of the Portuguese version of the SMOSS enables its application in the context of Portuguese PE classes, providing researchers with a tool to develop studies to identify and measure social goals in PE sport participation. It also enables the testing and estimation of causal relationships between observed and latent variables. This, in turn, facilitates a deeper understanding of the data and the relationships between the constructs measured by the questionnaire.

It is a suitable instrument for use by schools, teachers, and psychological counselors to assess PE students’ social goals and identify any difficulties in this area. Furthermore, the SMOSS can be used to help develop and evaluate intervention programs aimed at enhancing students’ social motivation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., C.F. and I.M.; methodology, C.B., S.M.d.S. and I.M.; validation, C.B. and S.M.d.S.; formal analysis, C.B., S.M.d.S. and C.F.; investigation, C.F. and C.B.; data curation, C.B. and S.M.d.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B., S.M.d.S. and I.M.; writing—review and editing, C.B., S.M.d.S., C.F. and I.M.; project administration, C.F. and I.M.; funding acquisition, C.F., C.B. and I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by national funds through FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology (grant number: 2022.08915.PTDC), under the project/support UIDB/05913/2020—Centre for Research, Education, Innovation and Intervention in Sport (CIFI2D).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University Ethics Board (Reference: CEFADE 38_2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Confidentiality was ensured. All the participants were provided with pseudonyms to protect their identities.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen, J. Social Motivation in Youth Sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2003, 25, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehr, M.L.; Nicholls, J.G. Culture and achievement Motivation: A Second look. In Studies in Cross-Cultural Psychology; Warren, N., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 2, pp. 221–267. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, J.G. The Competitive Ethos and Democratic Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, C.T. Achievement Motivation among Anglo-American and Hawaiian Male Physical Activity Participants: Individual Differences and Social Contextual Factors. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1996, 18, 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vealey, R.S.; Campbell, J.L. Achievement Goals of Adolescent Figure Skaters: Impact on Self-Confidence, Anxiety, and Performance. J. Adolesc. Res. 1988, 3, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J. Multiple achievement orientations and participation in youth sport: A cultural and developmental perspective. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1995, 26, 431–452. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, J. Generalization of Achievement Orientations for Experiences of Success and Failure in Youth Sport. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2004, 99, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, T.A.; Hayashi, C.T. Achievement Motivation among High School Basketball and Cross-Country Athletes: A Personal Investment Perspective. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2001, 13, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. Measuring social motivational orientations in sport: An examination of the construct validity of the SMOSS. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2005, 3, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, M.E. Achievement Orientations and Sport Behavior of Males and Females; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Champaign, IL, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, K.; Allen, J.; Smellie, L. Motivation in Masters sport: Achievement and social goals. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, L.; Kavussanu, M. Moral identity and social goals predict eudaimonia in football. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garn, A.; Ware, D.; Solmon, M. Student Engagement in High School Physical Education: Do Social Motivation Orientations Matter? J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2011, 30, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallhead, T.; Garn, A.C.; Vidoni, C. Sport Education and social goals in physical education: Relationships with enjoyment, relatedness, and leisure-time physical activity. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2013, 18, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garn, A.; Wallhead, T. Social Goals and Basic Psychological Needs in High School Physical Education. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2015, 4, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.; Roberts, A.M.; Zhang, G.; Taylor, S.G.; Fairchild, A.J.; Zarrett, N. Examining the factor structure and validity of the social motivational orientations in sport scale. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 22, 1480–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannatta, K.; Gartstein, M.A.; Zeller, M.; Noll, R.B. Peer acceptance and social behavior during childhood and adolescence: How important are appearance, athleticism, and academic competence? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.M. Examining the Factor Structure, Concurrent Validity, and Predictive Validity of the Social Motivational Orientations in Sport Scale (SMOSS) in an Early Adolescent Sample. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, D.S. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software Version 4.0 of the Free Statistics Calculators]. 2023. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89 (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford-Hemming, T. Determining Content Validity and Reporting a Content Validity Index for Simulation Scenarios. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2015, 36, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eys, M.; Loughead, T.; Bray, S.; Carron, A. Development of a Cohesion Questionnaire for Youth: The Youth Sport Environment Questionnaire. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 31, 390–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L.; Schachter, S.; Back, K. Social Pressures in Informal Groups: A Study of Human Factors in Housing; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, D.R. Recent advances in the study of group cohesion. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2021, 25, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.M.; Davies, K.M.; Carron, A.V. Group cohesion in sport and exercise settings. In Group Dynamics in Exercise and Sport Psychology, 2nd ed.; Beauchamp, M.R., Eys, M.A., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, C.G.; Thrower, S.N. Motivational climate in youth sport groups. In The Power of Groups in Youth Sport; Bruner, M.W., Eys, M.A., Martin, L.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, J.; Granja, C.; Fortes, L.; Freire, G.; Oliveira, D.; Peixoto, E. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the Youth Sport Environment Questionnaire (P-YSEQ). J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 1606–1614. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, T.; Peters, D.M.; Ommundsen, Y.; Martin, L.J.; Stenling, A.; Høigaard, R. Psychometric Evaluation of the Norwegian Versions of the Modified Group Environment Questionnaire and the Youth Sport Environment Questionnaire. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2021, 25, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K. Structural equation models. In Encyclopedia of Biostatistics; Armitage, P., Ed.; John Wiley: Sussex, UK, 1998; pp. 4364–4372. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mindrila, D. ML and Diagonally WLS Estimation Procedures: A comparison of estimation bias with ordinal and multivariate non-normal data. Int. J. Digit. Soc. 2010, 1, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos Teóricos, Software e Aplicações, 3rd ed.; Report Number: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, G.; Mueller, R.O. Rethinking construct reliability within latent variable systems. In Structural Equation Modeling: Present and Future; Cudeck, R., Jöreskog, K.G., Sörbom, D., Toit, S.D., Eds.; Scientific Software International Inc.: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2001; pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, G.; Mueller, R.O. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 2nd ed.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.; Lee, H. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.; Watson, D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.; Rensvold, R. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, Y. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, J.M.; Robbins, S.B.; Morril, W.H.; Boggs, K. Development and validation of the Career Factors Inventory. J. Couns. Psychol. 1990, 37, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluation structural equations models with unobservable variable and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. Researching social goals in sport and exercise: Past, present and future. In Sport and Exercise Psychology Research Advances; Simmons, M.P., Foster, L.A., Eds.; Nova Biomedical Books: Suite N Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, M.; Bridgeman, B. The evolution of the concept of validity. In The History of Educational Measurement: Key Advancements in Theory, Policy, and Practice; Clauser, B., Bunch, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizek, G. Validity: An Integrated Approach to Test Score Meaning and Use; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Van Ancum, J.; Bergquist, R.; Taraldsen, K.; Gordt, K.; Mikolaizak, A.S.; Nerz, C.; Pijnappels, M.; Jonkman, N.H.; Maier, A.B.; et al. Concurrent validity and reliability of the Community Balance and Mobility scale in young-older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, N.; Moneta, G.B. Construct and concurrent validity of the Positive Metacognitions and Positive Meta-Emotions Questionnaire. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furr, R.; Bacharach, V. Psychometrics: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazos, T. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).