Design Thinking in Higher Education Case Studies: Disciplinary Contrasts between Cultural Heritage and Language and Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Clarifications

1.2. Benefits of Transdisciplinarity and Design Thinking

1.2.1. Benefits of Transdisciplinarity

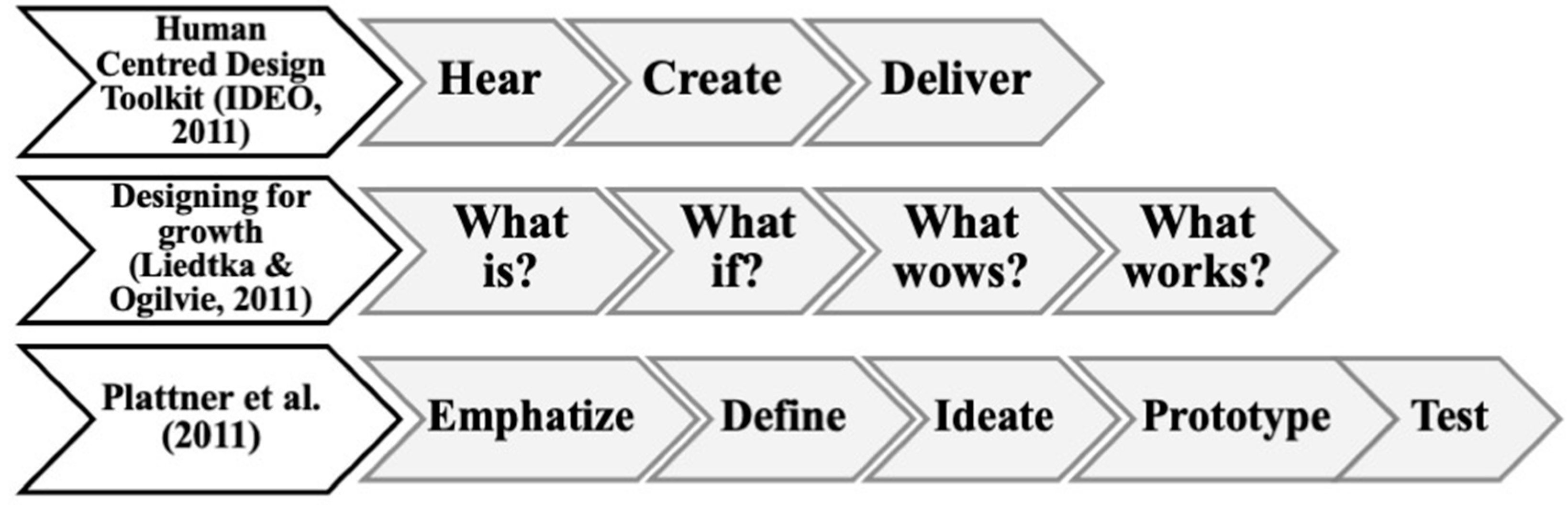

1.2.2. Design Thinking

2. Materials and Methods

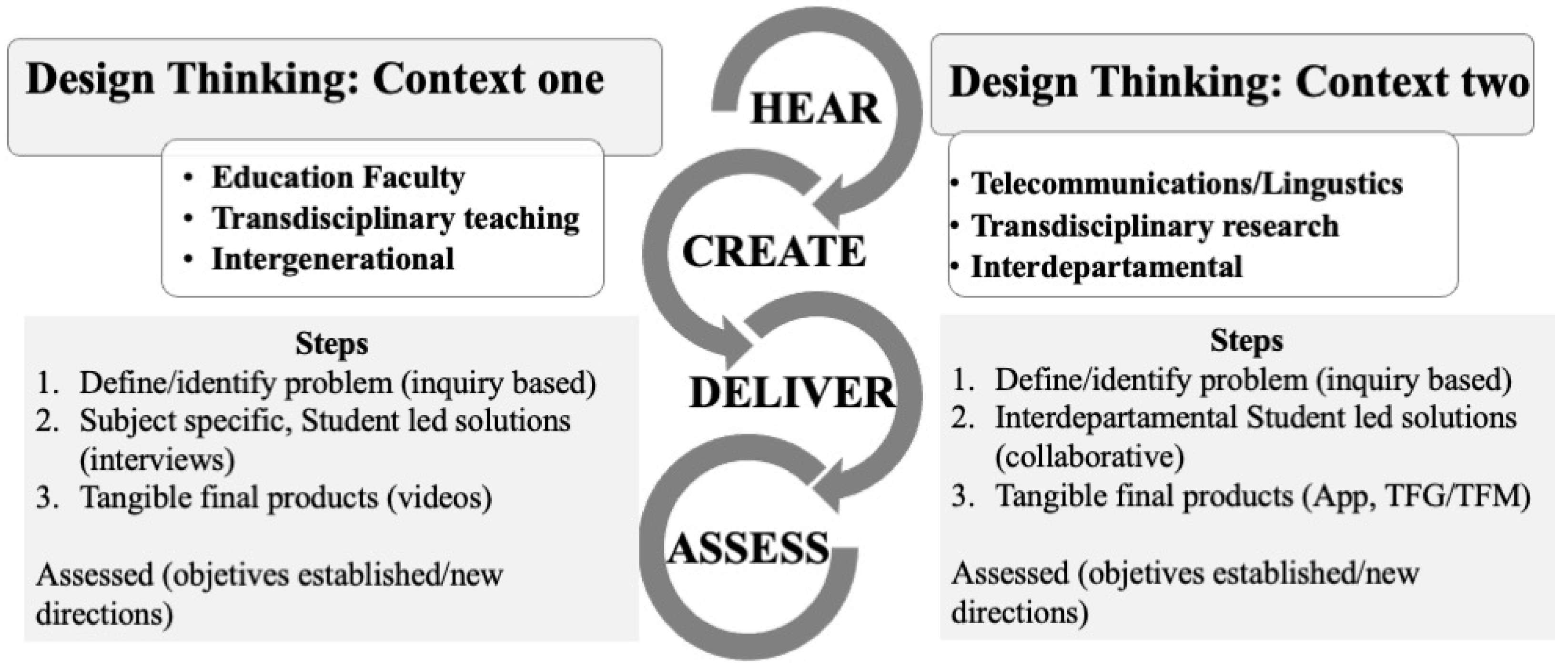

2.1. Case Study Contexts

2.2. Design Thinking Steps

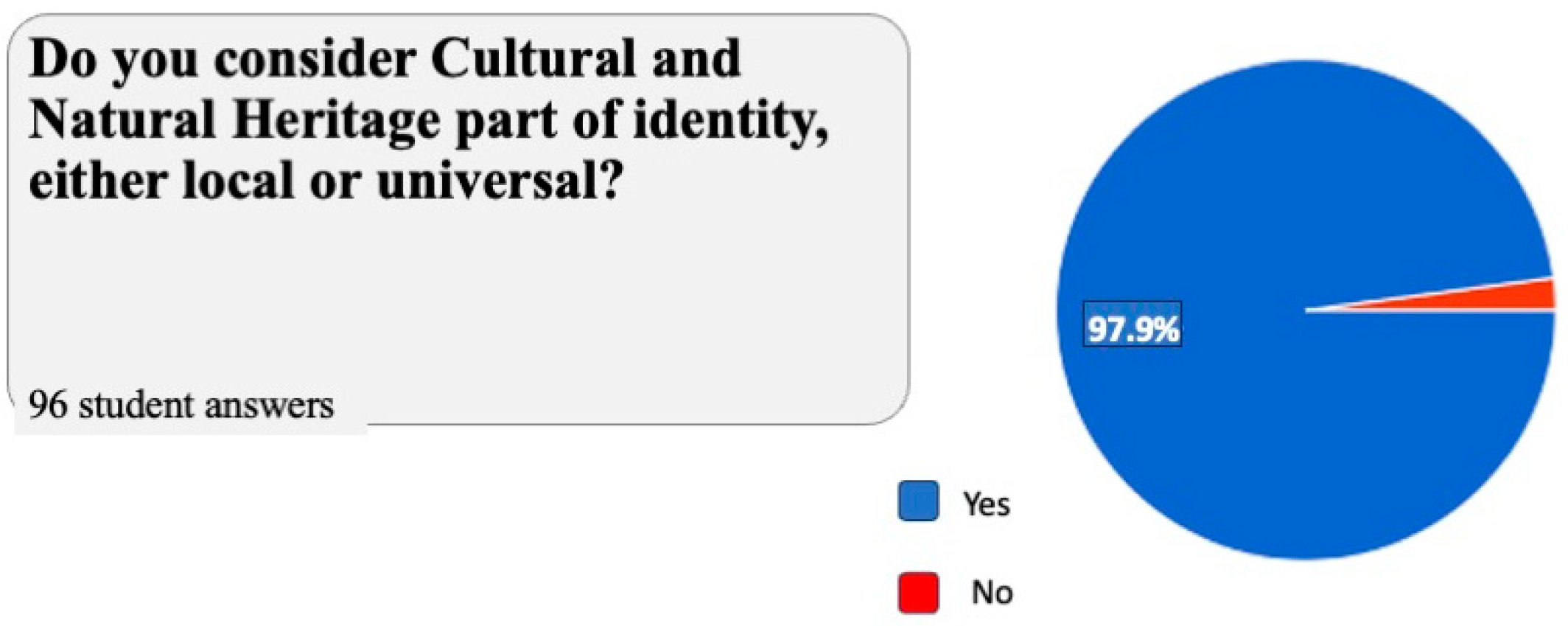

2.2.1. Step One: Hear

2.2.2. Step Two: Create

2.2.3. Step Three: Deliver (Preliminary Results)

- Red is impedance higher than 35 kΩ.

- Orange is impedance between 35kΩ and 20 kΩ.

- Yellow is impedance between 20 kΩ and 10 kΩ.

- Green is impedance less than 10 kΩ.

2.2.4. Step Four: Assess

- Depth of intergenerational dialogue [34] collected and quality of interview.

- Use of visual thinking strategies [20] and digital skills in the videos.

- Classroom debate regarding all projects with international insight from students.

- Degree of adequacy for dissemination of videos for educational purposes.

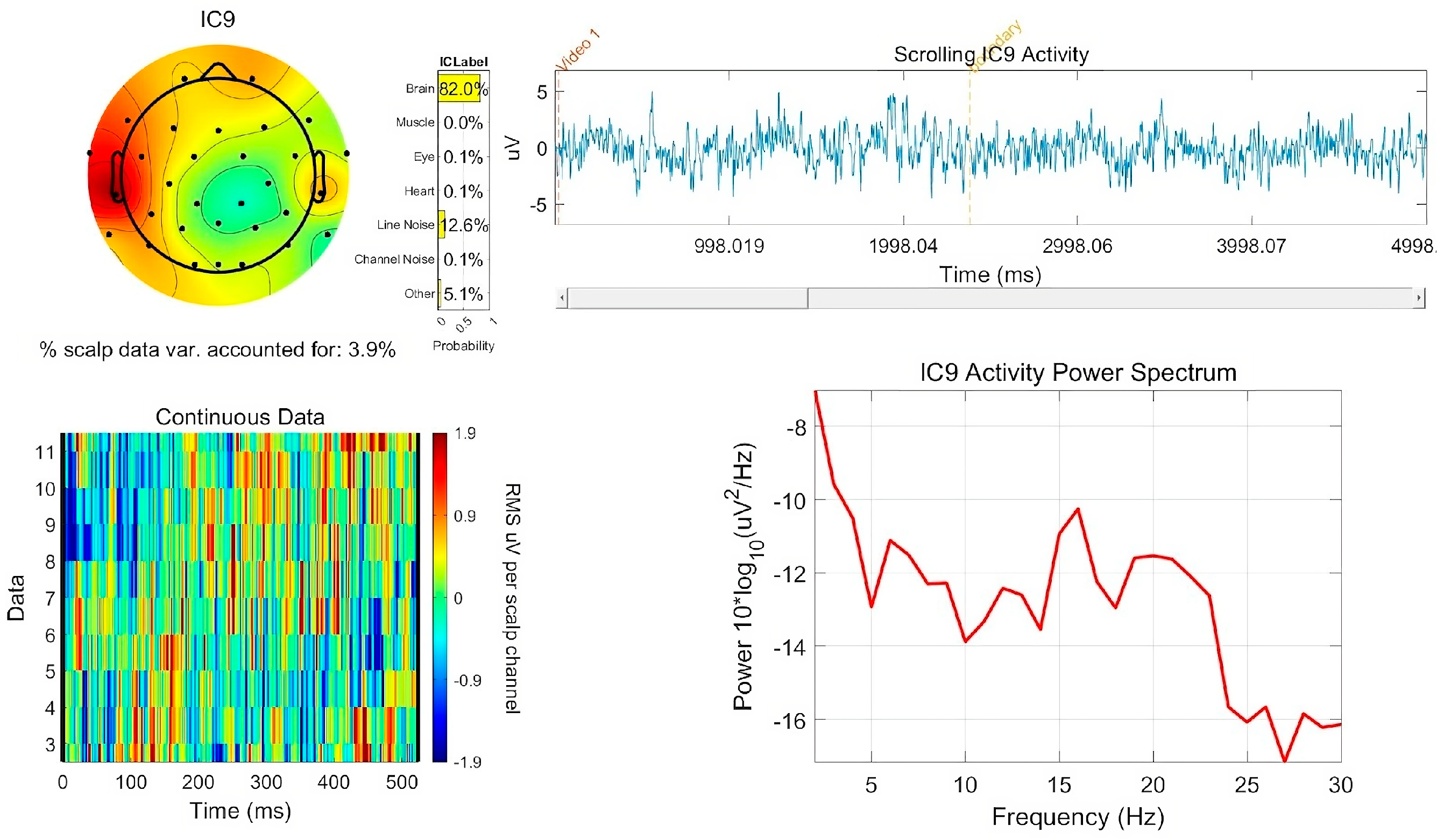

- The research identified which electrode was responsible for attention and then limited the stimuli to measure the response correlation.

- Specific linguistic artefacts were correlated with the attention electrode. Findings indicate that pauses or changes in intonation are ‘attention getting’ in EEG measurements [35] in the preliminary sample.

3. Results

3.1. Additional Findings and New Directions for Context One

3.2. Additional Findings and New Directions for Context Two

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of Present Study and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dalton, A.; Wolff, K.; Bekker, B. Interdisciplinary Research as a Complicated System. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolot, C. Transdisciplinarity as a discipline and a way of being: Complementarities and creative tensions. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, D.; Sánchez-García, R. Learning is moving in new ways: The ecological dynamics of mathematics education. J. Learn. Sci. 2016, 25, 203–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, D.T.; Uttamchandani, S.L.; Chartrand, G.T. Competencies in context: New approaches to capturing, recognizing, and endorsing learning. In Handbook of Research in Educational Communications and Technology; Bishop, M.J., Boling, M.J., Elen, E., Svihla, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 547–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, D.B.; Blair, K.P.; Wolf, R.C.; Conlin, L.D.; Cutumisu, M.; Pfaffman, J.; Schwartz, D.L. Educating and Measuring Choice: A Test of the Transfer of Design Thinking in Problem Solving and Learning. J. Learn. Sci. 2019, 28, 337–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvargonzález, D. Multidisciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity, Transdisciplinarity, and the Sciences. Int. Stud. Philos. Sci. 2011, 25, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geitz, G.; Geus, J.D. Design-based education, sustainable teaching, and learning. Cogent Educ. 2019, 6, 1647919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, M. (Ed.) Engaged Learning: Voices Across Europe; IDC Impact Series; Maklu Publishers: Antwerpen, Belguim, 2022; Volume 5, Available online: https://www.cast-euproject.eu/news/new-cast-anthology-now-available/15/ (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Winskel, M.; Ketsopoulou, I.; Churchouse, T. URWKC Interdisciplinary Review: Research Report. (Report No. NE/ G007748/1). UKERC. 2015. Available online: https://ukerc.ac.uk/ (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Siedlok, F.; Hibbert, P. The organization of interdisciplinary research: Modes, drivers and barriers. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentoft, D. From saying to doing interdisciplinary learning: Is problem-based learning the answer? Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, K.; Li, S. Matching Job Skills with Needs. In Business Times, 1; (1 October 2005); As cited in Thi Van Pham, Anh and Thi Thu Dao, Huong, The Importance of Soft Skills for University Students in the 21st Century; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Ponce, B.; Patiño, A.; Sanabria-Z, Z. Components of computational thinking in citizen science games and its contribution to reasoning for complexity through digital game-based learning: A framework proposal. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2191751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, N. Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work; Berg Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Von Thienen, J.P.A.; Weinstein, T.J.; Meinel, C. Creative metacognition in design thinking: Exploring theories, educational practices, and their implications for measurement. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1157001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novo, C.; Tramonti, M.; Dochshanov, A.M.; Tuparova, D.; Garkova, B.; Eroglan, F.; Uğraş, T.; Yücel-Toy, B.; Vaz de Carvalho, C. Design Thinking in Secondary Education: Required Teacher Skills. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.Y.; Tairab, H.; Qablan, A.; Alarabi, K.; Mansour, Y. STEM-Based Curriculum and Creative Thinking in High School Students. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F. Design Thinking: From Empathy to Evaluation. In Foundations of Robotics; Herath, D., St-Onge, D., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Change by Design; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Standen, C. The use of photo elicitation for understanding the complexity of teaching: A methodological contribution. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2021, 44, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Ligorred, V.; Ramos-Vallecillo, N.; Covaleda, I.; Fayos, L. Integration and Scope of Deepfakes in Arts Education: The Development of Critical Thinking in Postgraduate Students in Primary Education and Master’s Degree in Secondary Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kueh, C.; Thom, R. Visualising Empathy: A Framework to Teach User-Based Innovation in Design. In Visual Tools for Developing Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Capacity; Griffith, S., Carruthers, K., Bliemel, M., Eds.; Common Ground Research Networks: Champaign, IL, IL, USA, 2018; pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- IDEO. The Human-Centered Design Toolkit. 2011. Available online: https://www.ideo.com/post/designkit (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Liedtka, J.; Ogilvie, T. Designing for Growth: A Design Thinking Tool Kit for Managers; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Plattner, H.; Meinel, C.; Leifer, L. (Eds.) Design Thinking. Understand-Improve-Apply; Hasso-Plattner-Institute for Software Systemtechnik; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.; Niehaus, L. Mixed Method Design: Principles and Procedures; Left Coast Press Inc.: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerblad, L.; Seppänen-Järvelä, R.; Haapakoski, K. Integrative Strategies in Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2021, 15, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga-Jiménez, C.; Kurantowicz, E. (Eds.) Together for Cultural Heritage Booklet of Recommendations for Social Partners; Lower Silesia University Press: Wroclaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Chichón, J.L.; Sánchez-Cabrero, R. Cultural Awareness in Pre-Service Early Childhood Teacher Training: A Catalogue of British Cultural Elements in Peppa Pig. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture. Protecting our Heritage and Fostering Creativity. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/culture (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Griffith, M.; Lechuga-Jiménez, C.; Santos Diaz, I. Málaga: Multiple Directions for Engaged Learning. In Communities and Students Together (CaST) Piloting New Approaches to Engaged Learning in Europe; Marsh, C., Kilma, N., Anderson, L., Eds.; Maklu Publishers: Antwerpen, Belgium, 2022; pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fontal-Merillas, O.; Marín-Cepeda, S. Nudos Patrimoniales. Análisis de los vínculos de las personas con el patrimonio personal. Arte Individuo Y Soc. 2018, 30, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chicano, N. Rhythm and Intonation in Listener’s Attention Span: An Approach through Electroencephalogram Analysis. Master’s Thesis, University of Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yébenes-Gálvez, L. Matlab. Software Design in Attention in English Oral Discourse in International Settings: Linguistic Analysis Supported by Bioelectrical Measurements. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Villarejo Soler, C. Herramienta de Preprocesado y Extracción de Características Para Señales de EEG/ /A Tool for Preprocessing and Extracting Characteristics for EEG Signals. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Social Science | Engineering/English | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection procedure | The main instruments were 96 questionnaires, and then 50 semi-structured interviews. | This process begins with interdisciplinary design thinking. Data are collected with an EEG cap. The team selects variables and data sets making each step of the process more correlated and better defined. |

| Role of language | Language is a tool. The value of intergenerational dialogue has been interpreted and transferred to a digital representation of cultural patrimony. | Language and its relationship to attention are the object of the study. Students create a linguistic map of video stimuli to correlate features with EEG responses. |

| Role of technology | Technology is a tool. Students create videos using visual research methodologies (VRMs) and transfer narratives to a digital format. | Using the EEG cap makes technology part of the research. Students create specific technological applications that improve reliability of the data set by identifying brain regions tied to stimuli. |

| Final goal | The final goal is to explore cultural heritage using transdisciplinary design thinking to reach out to the community outside the university. From 63 videos, 13 videos were selected and specifically reinforced the value of people and patrimony. | The final goal is a series of tangible goals: first to filter EEG activity using software design in the Matlab app created for this purpose; next to correlate linguistic features to attention an ensure reliability; and, ultimately, to use this reliable data to ‘train the machine’ in future research. |

| Disciplinarity | C1 is transdisciplinary, student group is large and includes community. C2 is interdisciplinary, student group is small and focused on a series of research problems. |

| Research approach | C1 began with QUAN(qual)→QUAL data validated by the number of interviews, but led to further qualitative interpretation as students designed their videos. C2 began with quantitative data that required qualitative interpretation. By preselecting variables to prove specific correlations between brain activity and linguistic input, the approach moved from quantitative to qualitative interpretation. The human sample is small (13 subjects), but the raw data collected are enormous. |

| Language | C1: Language is a tool. The value of intergenerational dialogue was interpreted and transformed into a digital representation of cultural patrimony learning and divulgation. C2: Language and its relationship to attention and emotion are the object of the study. |

| Technology | C1: Technology is a tool to develop VRM. C2 Technology is a tool with the EEG measurements, but at the same time is developed in an applied way to solve research problems and better fit the data to a reliable model. |

| Outcomes and perspectives | Used for teaching: C1: Tangible products are quite wide ranging and in this selection the research looks to the past to explore how people and patrimony come together for present and future social understandings. Used for research: C2: The student-led projects moved the research forward. Research looks to the future to use this reliable model to ‘train the machine’ for AI using human responses. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Griffith, M.; Lechuga-Jimenez, C. Design Thinking in Higher Education Case Studies: Disciplinary Contrasts between Cultural Heritage and Language and Technology. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010090

Griffith M, Lechuga-Jimenez C. Design Thinking in Higher Education Case Studies: Disciplinary Contrasts between Cultural Heritage and Language and Technology. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(1):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010090

Chicago/Turabian StyleGriffith, Mary, and Clotilde Lechuga-Jimenez. 2024. "Design Thinking in Higher Education Case Studies: Disciplinary Contrasts between Cultural Heritage and Language and Technology" Education Sciences 14, no. 1: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010090

APA StyleGriffith, M., & Lechuga-Jimenez, C. (2024). Design Thinking in Higher Education Case Studies: Disciplinary Contrasts between Cultural Heritage and Language and Technology. Education Sciences, 14(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010090