Abstract

This study analyzes three competency areas promoted in the Practicum during the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 academic years: pedagogical and didactic competences, coexistence and participation management and collaborative work. To this end, using a non-experimental design, data were collected from a sample of 725 Education students from University of Salamanca with the aims of determining the students’ expectations about the Practicum prior to its development and of measuring its impact on the students during its development or the influence of the context imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research was contextualized in two Practicum subjects included in the curricula of the bachelor’s degrees in Early Childhood/Primary Education at the University of Salamanca. Both degrees are taught at three different university centers, Ávila, Salamanca and Zamora. The results revealed the importance of the preparation of the students in their university training period with regard to the first competence area, together with the perceptions of the students about what they learnt in the competences of areas 2 and 3. Relevant conclusions were drawn about their learning expectations towards the second area and the problems caused by the pandemic in order to develop communication skills with students and families.

1. Introduction

Teacher training degrees in Spain, both the Early Childhood Education degree and the Primary Education degree, have a compulsory subject of curricular practices, which constitutes 20% of the credits in teacher training, as established in the law through Orders ECI/3854/2007 and ECI/3857/2007, which regulate these university studies. Since the latest reforms of the curricula, which extended the time allocated to it, Spain has become one of the European countries that devotes the most time to practical training periods [1]. Between 500 and 600 total hours are allocated for the stay in the educational centers, generally in two or three periods during different academic years. The first period constitutes the initial stage of the stay in the school center, allowing observation and familiarization with the environment, the agents and the daily reality of the classroom. In the second one, the trainees’ knowledge of the educational system, the school reality and school–society relations is deepened, focusing on the understanding of the classroom and school life in its physical, social and academic dimensions [2].

These teaching, pedagogical, professional or external undergraduate curricular practices, also called Practicum, are among the most basic elements in teacher training [3,4], making it possible to bring students closer to the classroom context through professional teachers who tutor their learning process. It is the first professional introduction to the classroom reality, to its agents and to its teaching and assessment methods. In addition, it allows the theoretical–practical contents taught in the subjects of university degrees to be combined with the professional skills necessary to practice the teaching profession in real situations experienced in a specific educational center [3]. These Practicum periods represent unique periods in which theoretical knowledge and professional practice converge, generating multiple learning experiences that must be guided through critical reflection, while trying to ensure that previous training is effectively transferred to real experience with students [4]. For many university students, these school internships become the most complex, but also the most comprehensive, subjects of the training received in their curriculum.

This relevance requires the assessment and analysis of its impact to allow us compare how and the extent to which benefits for teachers’ training and professional futures are generated. In order to understand the effect of Practicum subjects on the training of future teachers, it is necessary to study the expectations towards the Practicum, as previous studies indicate that it is the most highly valued subject by students among all the formative options offered on teaching degrees, with expectations being a dimension that has scarcely been explored [5,6,7,8].

Initially, students tend to have a very positive attitude towards these subjects [9], because they know that a practical period will bring them closer to the reality of the classroom, of teachers and of students. However, recent studies suggest that it also arouses expectations and feelings of insecurity, fear or other negative emotions related to the profession [10,11]. Additional pieces of research indicate that trainees’ expectations are so decisive that they allow them to rehearse their notion of their professional role [7], which may or may not be close to teachers’ reality. This agrees with Peinado and Abril’s observation [12] that trainees’ expectations include a strong vocational idea that influences whether they reaffirm or decision to become education professionals during the Practicum.

Among the studies that have analyzed the effect of the Practicum subjects on initial ideas, attitudes, reflections, feelings or expectations, some argue that the Practicum brings both benefits and challenges. In the study by Hamaidi et al. [13], it was found that students enrolled in teacher training degrees found benefits through developing interactions and communication with students and classroom management skills, while the challenges detected included a lack of guidance from the Practicum supervisor, difficulty in communicating with teachers and a shortage of cooperation. Moussaid and Zerhouni [14] also found challenges regarding classroom control and time management. Bulgakova et al. [15] found that hurdles were associated with insecurity in feeling unprepared for professional activity. Cretu [16] also highlights that the Practicum is a mixed experience for teacher-training-degree students. Thus, the benefits include establishing a professional relationship, developing personal and professional skills and attitudes, and understanding the educational system, while challenges are associated with the implementation of teaching and the management of coexistence in the classroom.

The analysis of expectations, both positive and negative, was even more relevant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the measures implemented in classrooms and in schools [17,18,19] were aimed at facilitating face-to-face teaching in a safe context, they could have affected the development of the Practicum for students on teacher training degrees. Thus, it is possible that Practicum students might have had limited opportunities to establish contact, communication and interaction with teaching staff in schools, to hold meetings with families to discuss follow-ups in tutorials or to establish links with students in schools [20,21,22,23]. On the other hand, students also appreciated positive aspects, in relation to the use of technology and the improvement of their digital competences [22,24,25], as well as regarding the possibilities offered by online learning in the educational process in any circumstance [21,23,26].

Therefore, this study focuses on determining students’ expectations about the educational usefulness of this subject prior to its development, together with the perceived teacher competences acquired by the students. For this analysis, international teacher competency frameworks, such as the European Commision Teacher Competencies framework [27,28], as well as others that have also been published in the OECD context [29,30,31], are used as references to select the competences or competence areas that teachers need to have in order to be effective in their work. The comparative analysis first found seven competences that could be linked to the training objectives of the Practicum subject. The seven competences were then grouped into three competence areas, as described below:

Area of Pedagogical and Didactic Competences. This refers to the ability to plan, design and carry out teaching–learning activities (the design of teaching units, the preparation of educational materials and the assessment of learning, among others). In addition, some reports include other related competences in this area: attention and adaptation to diversity and inclusion (students with special educational needs or belonging to different cultures and social contexts); digital teaching competence, which has its own entity with specific frameworks, but is also associated with the planning and development of teaching by integrating educational technologies in teaching and interaction processes; and other essential competences for teacher-training-degree students to develop the ability to reflect on their teaching practice and assess their own performance, through self-reflection and improvement competences.

Area of Coexistence and Participation Management. In this area, teachers should be able to establish a positive classroom environment to promote learning. This includes the ability to manage student behavior, encourage active participation and maintain discipline in a constructive way. In addition, it includes the competences highlighted in reports as competence for relationships and communication, which involve the acquisition of effective skills to facilitate interactions in the classroom and the educational environment, both with other teachers and with families.

Area of Competences for Collaborative Work. Teachers are expected to learn to work in teams with other teachers and professionals in the field of education. This collaboration is associated with teachers’ professional development, which allows them to share ideas, experiences and resources to improve their teaching practice and enrich their students’ learning.

On the basis of this analytical review and considering the regulations governing training tasks and the acquisition of competences in the Practicum in Spain for the degrees of Early Childhood Education and Primary Education, 10 competences and eight training objectives were considered for analysis in this study, which are related to the three areas of competence highlighted (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Areas, competences and training objectives of the teacher training Practicum considered in the study.

Therefore, this study is focused on establishing whether the classroom experiences of university students were in line with their initial expectations of achieving of different learning objectives. Additionally, this study analyzes the influence of the context imposed during the pandemic by COVID-19 and the limitations of social distancing, which could have affected both the trainees’ expectations and their perceptions of their achievement of the competencies required in the subject.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Context

The study was carried out using a non-experimental design, with a descriptive methodology and cross-sectional inference.

The research was contextualized in the two Practicum subjects (I-initial or observation and II-final or intervention), which are included in the curricula of the bachelor’s degrees in Early Childhood Education and Primary Education at the University of Salamanca [32]. Both degrees are taught at three different university centers, the University School of Education and Tourism in Ávila, the University School of Teaching in Zamora, and the Faculty of Education in Salamanca. With regard to the timing of the research, it took place during the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 academic years, and it was developed in an exceptional situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2).

Table 2.

Areas, competences and training objectives of the teacher training Practicum considered in the study.

2.2. Participants

The study population consisted of all students enrolled in the external practice subjects of the bachelor’s degrees in Early Childhood Education and Primary Education at the University of Salamanca, in the academic years 2020–2021 and 2021–2022. The study sample comprised 725 students, aged between 20 and 42 years (22.15 ± 2.82). Female participation was higher (80.6%), which is in line with the general trend in education studies. The majority of students belonged to the Primary Education degree (65.2%), in line with the ratio of places on both degrees. Finally, the participation of students from the three schools was fairly equal. Table 3 shows the socio-demographic profile of the Practicum students in more detail.

Table 3.

Socio-demographic profile of the students who participated in the study (n = 725).

2.3. Instrument

The data collection instrument was a questionnaire prepared ad hoc for the study and made up of four sections. The first section consisted of socio-demographic data collected through 11 items (gender, age, school, grade, year, record, subject, specialty, typology, tenure and preferred choice of school). In the second section, building on the work of Hamaidi et al. [13], eight items were presented on students’ expectations regarding the achievement of the different formative objectives of the Practicum (e.g., develop my interaction skills, acquire classroom management skills, etc.). The same eight items were also presented to assess the students’ perceptions of the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their achievement of the different Practicum learning objectives. The content and structure of the questionnaire were analyzed, with particular attention to the order and wording of questions. Special care was taken to avoid the introduction of biases inherent in self-administered questionnaires, such as social desirability bias, acquiescence bias, recall bias, and logic bias. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that the chosen method of data collection represents a limitation of this research. The reliability index obtained for the scale as a whole was α = 0.865. The third section included 10 items about the competences worked on during the Practicum, based on those selected in the theoretical framework, as well as asking about the influence of the pandemic on these competences. The reliability index obtained for the scale was α = 0.881. In both sections, the response options were presented on a five-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability coefficient for the internal consistency of the entire questionnaire was satisfactory (Cronbach’s α: 0.839).

2.4. Data Gathering

Prior to data collection, the Practicum coordinators of three university campuses were contacted in order to inform them about the study and obtain from the respondents their informed consent to participate. Data collection was carried out through voluntary participation by means of a self-administered questionnaire via email, with the link to the instrument attached, with guarantee of anonymity. It was elaborated using the Google Forms tool, selected on the basis of criteria of functionality and operability for the participants. The questionnaire was administered to students during their last week of work experience, situated at two different points in time: the beginning of February, in the case of Practicum I, and the end of April, for Practicum II. The questionnaires were completed voluntarily and anonymously, with prior express consent. To ensure data protection, the research process adhered to the ethical standards mandated by the University’s Ethical committee, in accordance with both Spanish and European data protection regulations.

2.5. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS v28.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Normality and homogeneity of the sample were examined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics were calculated for continuous variables and qualitative variables to determine the relationship between the characteristics of the participants and the study variables. A Pearson correlation analysis was also performed to observe the relationship between factors. Differences between variables were analyzed using chi-squared tests (frequency distribution) and the Mann–Whitney U test for pairwise contrasts, given the lack of normality (comparison of means). Each item was used as a dependent variable, considering the sociodemographic variables of academic year, degree (training teacher) and subject (Practicum period) as grouping variables. The magnitudes of the differences or effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d, interpreting the effects as null (0–0.2), low (0.20–0.50), moderate (0.50–0.79) or high (0.80). Significance was be set at the p < 0.05 level.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

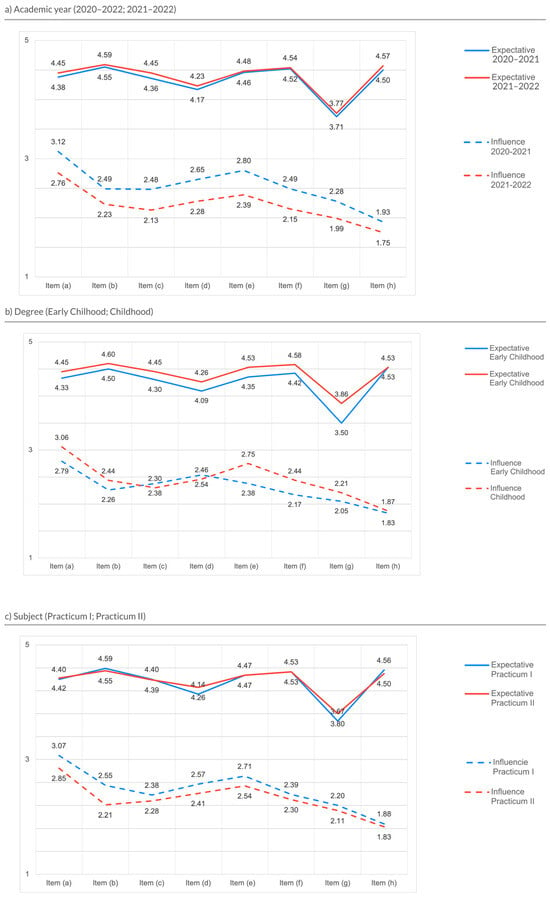

In order to determine the students’ perceptions of their expectations regarding the training objectives of the Practicum and the influence of COVID-19 on their achievement of these, the mean values obtained from the scores were used, considering the academic years, the degree program and the periods of the Practicum (Table 4).

Table 4.

Descriptive data on the expectations of the Practicum and the influence of COVID-19 according to academic year, degree and subject.

Regarding the students’ expectations in relation to the training objectives of the Practicum, for the total number of participants, the results showed that the best-rated competence was “(b) acquiring skills to manage/manage the classroom” (M = 4.57 SD = 0.72), followed by “(f) learning to prepare and plan teaching” (M = 4.53, SD = 0.80) and “(h) reaffirming my decision and vocation to be a teacher” (M = 4.57, SD = 0.72). On the other hand, the worst-rated was “(g) preparing educational software to support teaching” (M = 3.74, SD = 1.14). Regarding the influence of pandemic-related restrictions and security measures, overall, the students rated as the most negative aspects “(a) developing interaction and communication skills with students and families” (M = 2.96, SD = 1.23) and “(e) developing and diversifying teaching methods and strategies” (M = 2.62, SD = 1.31). On the other hand, the least influential aspect for the students was “(h) reaffirming the decision and vocation to be a teacher” (M = 1.85, SD = 1.30).

The disaggregated analysis, considering the academic year, degree and internship period, is shown in Figure 1. The results reveal that, in terms of expectations in teaching development, the mean scores were slightly higher for all the items in the academic year 2021–2022. This difference is also evident in the comparison of the influence of COVID-19 on these expectations, since this influence was significantly higher in the academic year 2020–2021. Considering now the degree program, the mean scores for the Practicum expectations were slightly higher for all the items for the students on the Primary Education degree program. However, this trend does not correspond to the comparison of the influence of the pandemic on these expectations, since the students from the Early Childhood Education degree program stated that it had a greater influence on items c and d. In the comparison on the placement period, the mean scores for the Practicum expectations were similar for all the items. On the other hand, in the comparison of the influence of COVID-19 on these expectations, the students in the first period rated the influence of the pandemic higher for all the items.

Figure 1.

Expectations towards the Practicum and the influence of COVID-19 according to academic year, degree and subject.

In order to determine the students’ perceptions of the competences they developed during their placements, we used the mean values obtained from the scores, considering the academic years, the degree programs and the placement periods (Table 5).

Table 5.

Descriptions of the competences developed in the Practicum according to academic year, degree and subject.

With regard to the competences developed in the Practicum, for the total number of participants, the results showed that the highest-rated competence was “1. Acquire classroom management skills” (M = 4.58, SD = 0.64), followed by “2. Develop social and communicative skills to turn the classroom into a place of learning and coexistence” (M = 4.50, SD = 0.70) and “5. Identify my functions as a teacher and develop them” (M = 4.50, SD = 0.72). On the other hand, the worst-rated was “9. Knowing and putting into practice contact and relations with families” (M = 3.29, SD = 1.39) and “8. Knowing ways of collaborating with the different sectors of the educational community and the social environment” (M = 3.83, SD = 1.13).

The disaggregated analysis, considering the academic year, degree and internship period, is shown in Figure 2. Regarding the academic year, the students’ scores were better for all the items except item 10 in the 2021–2022 academic year. With regard to degree and internship, the scores were similar in both comparisons.

Figure 2.

Competences developed in the Practicum according to academic year, degree and subject.

3.2. Inferential Analysis

In order to explore significant differences between the students’ perceptions of their expectations of the Practicum and the influence of the pandemic’s consequences, an inferential analysis was carried out according to academic year, degree and placement period (Table 6).

Table 6.

Inferential analysis of the expectations of the Practicum and the influence of COVID-19 according to academic year, degree and subject.

With regard to the students’ expectations of the training objectives of the Practicum, no significant differences were found in the comparison by academic year or Practicum period. With regard to the comparison by degree, significant values were obtained for objectives (d), (e) and (g), with the average rank of the Primary Education degree being higher than that of Early Childhood Education in all three. With regard to the scores for the influence of COVID-19 on the Practicum training, the results reveal significant differences. Regarding the students’ scores on the influence of COVID-19, the results reveal significant differences for all the items except objective (h) between the two academic years, with the mean rank of the 2021–2022 academic year being lower than that of the 2020–2021 academic year for all of the items. Significant values were also obtained in the comparison by degree (expectations a, b, e and f), and by internship (in a and b). For all of the items, a null effect size was found (<0.20).

Similarly, in order to explore the significant differences between the students’ perceptions of the competences they developed during the Practicum, an inferential analysis was carried out according to academic year, degree and Practicum period (Table 7). The results reveal significant differences between the academic years 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 for all the items except competence 10. Significant values were also obtained for items 6, 7, 8 and 10 between the practical periods.

Table 7.

Inferential analysis of the competences developed in the Practicum according to academic year, degree and subject.

4. Discussion

After analyzing the data collected, in this study, we can highlight some issues that open a space for reflection and connection with observations in other studies. Firstly, after the number of items assessed among the expectations and competences worked on in the Practicum, the importance of the subject in teacher training and the need to continue to study in depth the previous expectations of future teachers seem to have been evidenced, as in other studies [10]. University training is mainly theoretical and the achievement of competences requires a context of performance and practical application, such as in the Practicum, which manages to overcome the gap that still exists between the ways of learning in real professional contexts and that which often occurs in academic contexts, despite the recurrent call for coordinating actions between the two contexts, theorical and practical [1,4,37,38,39].

From the analysis of the students’ expectations, two relevant aspects for teacher training can be highlighted. Firstly, that the students’ learning expectations in the professional context focus on the second of the areas mentioned (competences for managing coexistence and participation in the classroom), because, when asked about the main limitations imposed by the pandemic, the participants in this study stated that their interaction and communication skills could not be fully developed because of the pandemic, as other studies confirmed [20,23]. Secondly, pedagogical and didactic competences, which the students would be expected to gain relatively rapidly, were in second place, suggesting that internship periods should prepare trainees to know how to plan teaching. Furthermore, that the main limitations were associated with the impossibility of diversifying teaching methods because of the social restrictions that impeded interaction, an issue that was not highlighted by previous. The third area, competences for collaborative work and professional development, was not particularly prominent among the students’ expectations, although it is clear from their answers that the limitations due to the pandemic did not influence their reaffirmation of their commitment to the profession, and that they accepted that it was an exceptional situation. This progression towards a more positive view of their learning expectations was verified in the comparative analysis by academic year or by typology, which demonstrated that at the beginning of the pandemic, the trainees’ expectations were lower and as the evolution was positive, so were their expectations. Interestingly, by degree, the students on the Early Childhood Education Teaching degree expressed lower learning expectations than the students on the Primary Education Teaching degree, although they had higher expectations related to the third area, competences for collaborative work and professional development.

In relation to the ten competences that were analyzed, the students seem to have considered that they were more prepared by their university training with regard to the pedagogical and didactic competences (the first area) because these were not the aspects that they valued as being most developed during their work placements. However, they considered that they had learnt the most in the competences of area 2, the competences of managing coexistence and participation, as well as those of area 3, especially knowing how to identify their functions as teachers in the classroom reality and knowing how to collaborate with the different agents of the educational community. These results are relevant for the future, for the revision of teacher training curricula, through which the training of students in these aspects of improving coexistence and the creation of teacher-collaboration networks could be reinforced.

In short, the importance for trainee teachers of learning related to the reality of the classroom and the school environment cannot be ignored, because it is a major factor for the growth of teachers who are beginning their professional development [40,41]. Thus, it is essential to continue working on competences and areas related to professional development through training at universities, so that internships are not students’ first encounters with reality. Similarly, other studies confirmed the use of case studies or other methods of approaching classroom situations and interactions, such as by presenting new conflicts and existing circumstances, so that undergraduate students can undergo training in practical strategies, considering that in the future, further tools and knowledge for prevention will be needed [42].

Another aspect that was also shown to be lacking during the practice processes that took place during the pandemic was the possibility of knowing and understanding what happens in the school context, which also extends to families, as other studies have shown [43]. Thus, it is worth highlighting the students’ assessment of the problems caused by the pandemic in order to develop interaction and communication skills with students and families. Similar studies with Practicum students have identified the relationship between the school and the family as fundamental, and it is necessary to reflect on how to reinforce and include this learning around tutorial action and new channels of communication between these stakeholders [43].

The impact of digitalization, which was forced upon many didactic and pedagogical interactions during the pandemic, is barely noticeable in the results. Although the teaching-and-learning process was carried out in virtual environments during the period of confinement, the reality unleashed by the pandemic was highly challenging for higher education. This was especially evident in terms of the ability of the higher education system to respond to the common hurdles with which it had dealt with for years: the fleeting era of digitalization and the sometimes problematic and dehumanizing communication through screens [44]. In this study and in the context of the limitations of the pandemic in schools, the Practicum students did not emphasize that they were going to learn about digital teaching methods, given that in our country, distancing measures were implemented to ensure safety. At the same time, this revealed shortcomings in learning that were affected by the limitations on interaction.

In this sense, the evidence for the negative influence of isolation during the pandemic was clear, including the evidence in our study, in which the students on both degrees perceived more or less equal differences between the more restrictive first year 2020–2021 and the following year. Thus, the prioritization of direct contact between the different actors in the educational community and its effect on decreasing contagion made clear the importance of education as interaction. This is a concern that was also highlighted in some of the other studies mentioned above [20,23]. Further research is needed to reaffirm these or other ideas in post-pandemic contexts to establish whether the pandemic context and the improvement that occurred, for example, through the renewed contact between different educational agents, has benefited professional training

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to incorporating elements of reflection into the analysis of academic competences and to the study of their relationship with other, non-academic gains acquired through the trainee teachers’ Practicum. The study emphasized the significance of students’ perceptions and expectations about the learning acquired in the Practicum, since if of competence gains in certain areas are expected, there will be a tendency to perceive the acquisition of competences in these areas, even if the Practicum process takes place in unusual circumstances, such as the pandemic. The results can also be used for future comparative studies to verify whether students from other universities, national or international, perceive gains in the pedagogical and didactic aspects in a similar manner those observed in this research or in other areas. In addition, this study also helps to understand the evolution of teacher training plans and to understand how prepared students perceive themselves to be in the three areas of competence to develop their Practicum, which is the prelude to their professional reality.

Author Contributions

Authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

After consultation with the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Salamanca, the committee determined that the evaluation was not necessary, as none of the research questions could identify the participants, guaranteeing their anonymity.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The study was developed under the framework of the project: Banco de casos prácticos basados en el Modelo de Competencias Profesionales del Docente de Castilla y.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Egido-Gálvez, I.; López-Martín, E. Condicionantes de la conexión entre la teoría y la práctica en el Prácticum de Magisterio: Algunas evidencias a partir de TEDS-M. Estud. Sobre Educ. 2016, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Verger-Gelabert, S.; Riera-Negre, L.; Roselló-Ramón, M.R.; Mut-Amengual, B. Análisis del Prácticum de Educación Infantil y Primaria en las universidades españolas. Aula Abierta 2023, 52, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Sanmamed, M.; Fuentes Abeledo, E.J. El practicum en el aprendizaje de la profesión docente. Rev. Educ. 2011, 354, 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselló Ramon, M.R.; Ferrer Ribot, M.; Pinya Medina, C. ¿Qué competencias profesionales se movilizan con el Practicum? Algunas certezas que manifiesta el alumnado. REDU Rev. Docencia Univ. 2018, 16, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, E.; Iglesias, M.T.; García, M.S. Desarrollo de competencias en el Prácticum de Magisterio. Aula Abierta 2008, 36, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liesa, M.; Vived, E. El nuevo prácticum del grado de magisterio. Aportaciones de alumnos y profesores. Estud. Sobre Educ. 2010, 18, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáiz-Linares, A.; Ceballos-López, N. El practicum de magisterio a examen: Reflexiones de un grupo de estudiantes de la Universidad de Cantabria. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Super. (RIES) 2019, 27, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicario, I.V.; Serrano, M.J.H.; Cilleros, M.V.M. Expectativas e impacto de la pandemia en el desarrollo del Practicum del Grado en Maestra/o en Educación Infantil y Primaria en la Universidad de Salamanca. In XVI Symposium Internacional Sobre el Practicum y las Prácticas Externas. Prácticas Externas Virtuales versus Presenciales: Transformando los Retos en Oportunidades para la Innovación; ACTAS: Poio, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- González-Garzón, M.L.; Laorden, C. El Prácticum en la formación inicial de los Maestros en las nuevas titulaciones de Educación Infantil y Primaria: El punto de vista de profesores y estudiantes. Pulso Rev. Educ. 2012, 35, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T.; Hagenauer, G. Openness to theory and its importance for student teachers’ self-efficacy, emotions and classroom behaviour in the practicum. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 77, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, J. El practicum en educación superior. Algunos hitos, problemáticas y retos de las tres últimas décadas. REDU Rev. Docencia Univ. 2020, 18, 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Peinado, M.; Abril, A.M. El Máster en Profesorado de Secundaria desde dentro: Expectativas y realidades del Practicum. Didáctica Cienc. Exp. Soc. 2016, 30, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaidi, D.; Al-Shara, I.; Arouri, Y.A.; Awwad, F.A. Student-teacher’s perspectives of practicum practices and challenges. Eur. Sci. J. 2014, 10, 191–214. [Google Scholar]

- Moussaid, R.; Zerhouni, B. Problems of pre-service teachers during the practicum: An analysis of written reflections and mentor feedback. Arab. World Engl. J. 2017, 8, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgakova, O.; Krymova, N.; Babchuk, O.; Nepomniashcha, I. Problems of the Formation of Readiness of Future Preschool Teachers for Professional Activities. Rev. Rom. Educ. Multidimens. 2020, 12, 169–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, D.M. Practicum in Early Childhood Education: Student Teachers’ Perspective. Rev. Rom. Educ. Multidimens. 2021, 13 (Suppl. 1), 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Medidas de Prevenicón, Higiene y Promoción de la Salud Frente al COVID-19 para Centros Educativos en el Curso 2020–2021; Ministerio de Sanidad y Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Recomendaciones del Ministerio de Universidades a la Comunidad Universitaria para Adaptar el Curso Universitario 2020–2021 a una Presencialidad Adaptada y Medidas de Actuación de las Universidades Ante un Caso Sospechoso o uno Positivo de COVID-19; Gobierno de España, Ministerio de Universidades: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Presidencia del Gobierno. Grupos de Convivencia Estable, Distancia Interpersonal y uso de la Mascarilla en los Centros Educativos; Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saraç, S.; Tarhan, B.; Gülay Ogelman, H. Online practicum during pandemic:“they’re in the classroom but i’m online”. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2023, 44, 773–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, F.A.; Aziz, A.A. Teaching practicum during COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the challenges and opportunities of pre-service teachers. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Díaz, L.; Delicado-Puerto, G.; Ramos, F.; Manchado-Nieto, C. Student Teachers’ Classroom Impact during Their Practicum in the Times of the Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camús, M.D.M.; Arroyo, S.; Lozano Cabezas, I.; Iglesias Martínez, M.J. El aprendizaje profesional docente en prácticas adaptado al contexto de la pandemia: Estudio cualitativo. In Nuevos Retos Educativos en la Enseñanza Superior Frente al Desafío COVID-19; Satorre Cuerda, R., Ed.; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2021; pp. 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kiok, P.K.; Din, W.A.; Said, N.; Swanto, S. The Experiences of Pre-service Teachers Teaching Practicum During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Couns. 2021, 6, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal, F.C.; Reyes, L.S.; González, M.M.; Toro, L.L.; Cofré, P.P.; Muñoz, F.A.; Casanova, C.P.F. Prácticum virtual en Educación Física: Entre pandemia e incertidumbre. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2021, 42, 798–804. [Google Scholar]

- Tekel, E.; Bayir, Ö.Ö.; Dulay, S. Teaching Practicum During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparison of the Practices in Different Countries. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2022, 18, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Common European Principles for Teacher Competences and Qualifications; Directorate-General for Education and Culture: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Supporting the Teaching Professions for Better Learning Outcomes; Commission staff working document: Strasbourg, France, (SWD (2012) 374 final); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- OCDE. Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers, Education and Training Policy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- OCDE. Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Environments: First Results from TALIS; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- OCDE. Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 Conceptual Framework; OECD Education Working Papers No. 187; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad de Salamanca. Guía del Prácticum de Maestros; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Escolar del Estado. Situación Actual de la Educación en España a Consecuencia de la Pandemia; Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad de Salamanca. Protocolo de Actuación COVID-19 (Curso 2020–2021); Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Medidas COVID-19 para Centros Educativos en el Curso 2021–2022; Ministerio de Sanidad y Ministerio de Educación y Formación: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad de Salamanca. Presencialidad Segura; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner, K. Nuevas epistemologías en formación del profesorado. Repensando las conexiones entre las asignaturas del campus y las experiencias de prácticas en la formación del profesorado en la Universidad. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2010, 24, 123–149. [Google Scholar]

- Zabalza, M.A. El Practicum en la formación universitaria: Estado de la cuestión. Rev. Educ. 2011, 354, 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, M.M.; Covarrubias, C.G. Competencias profesionales movilizadas en el prácticum: Percepciones del estudiantado del grado de maestro en educación primaria. Rev. Electrónica Actual. Investig. Educ. 2014, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cisternas, T.E. Profesores principiantes de Educación Básica: Dificultades de la enseñanza en contextos escolares diversos. Estud. Pedagógicos 2016, 42, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sáiz, A.; Susinos, T. Problemas pedagógicos para un Prácticum reflexivo de Maestros. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2017, 28, 993–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.; Pino, M.R. Las conductas problemáticas en el aula: Propuesta de actuación. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2008, 19, 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, A.; García-Ruiz, M.R.; Maraver, P. Impacto del practicum en las creencias de los maestros en formación sobre la relación familia-escuela. Rev. Bras. Educ. 2018, 23, e230028. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, G.M.; De los Ángeles Miró, M.; Stratta, A.E.; Mendoza, A.B.; Zingaretti, L. La educación superior en tiempos de COVID-19: Análisis comparativo México-Argentina. Rev. Investig. Gestión Ind. Ambient. Segur. Salud Trab.-GISST 2020, 2, 35–60. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).