Unknown Is Not Chosen: University Student Voices on Group Formation for Collaborative Writing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Collaborative Writing in Groups

2.2. Group Formation

2.3. Research Questions

- What are university students’ preferences regarding teacher-assigned versus student-selected group formation for collaborative writing and why?

- Which motives do university students consider when self-selecting a specific group partner for a collaborative writing task?

- 3.

- To what extent do students select a partner similar to themselves and what are the types of similarities among the groups?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

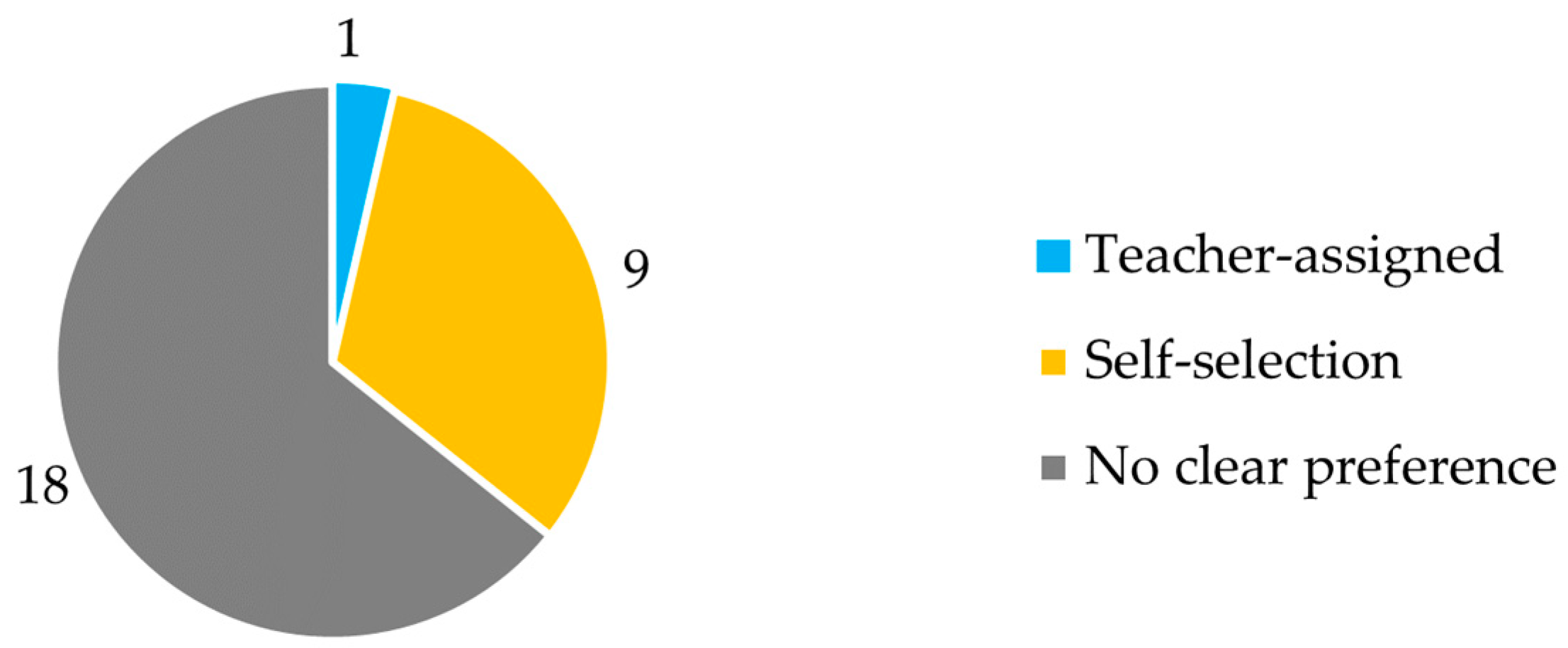

4.1. RQ1: Preferences for Student-Selected or Teacher-Assigned Group Formation and Reasons

“On one side, I find it [i.e., student-selection] important, because I can somehow predict how I can collaborate with that person. But if I would be assigned to a group, I would not mind. In the end, that could also be someone I like”.—Nicholas, group 14

“Then I just know for sure how the task will be executed, and that it will also be fun to call each other. I always look forward to chat once in a while. Otherwise it would be very formal, if you don’t know someone well. And I do think that everyone in our class has good results, but it’s more fun with someone you already have some sort of relationship with, I think”.—Megan, group 15

“Last year we couldn’t choose our partner for a task, and that way, it was a very difficult paper to write. Because you can’t judge that person very well. You don’t know if they take their study seriously or not and you don’t know if they tend to procrastinate or not […] Does our writing style match a little or not…”—Scarlett, group 4

“For me, it was a little bit frightening not knowing if I would be able to end up in a dyad. Is the student number even or odd… But actually, I do not mind that much [i.e., self-selecting a partner or being assigned to a group]”.—Robin, group 1

“I’ve been in a specific circle of friends since last year and I notice that when we are allowed to choose, we always divide it among that circle of friends, […] but… some of the other people in my circle I like as a person, but I find it more difficult to work with them. And we can say that to each other but even then we choose a partner within our circle”.—Lauren, group 6

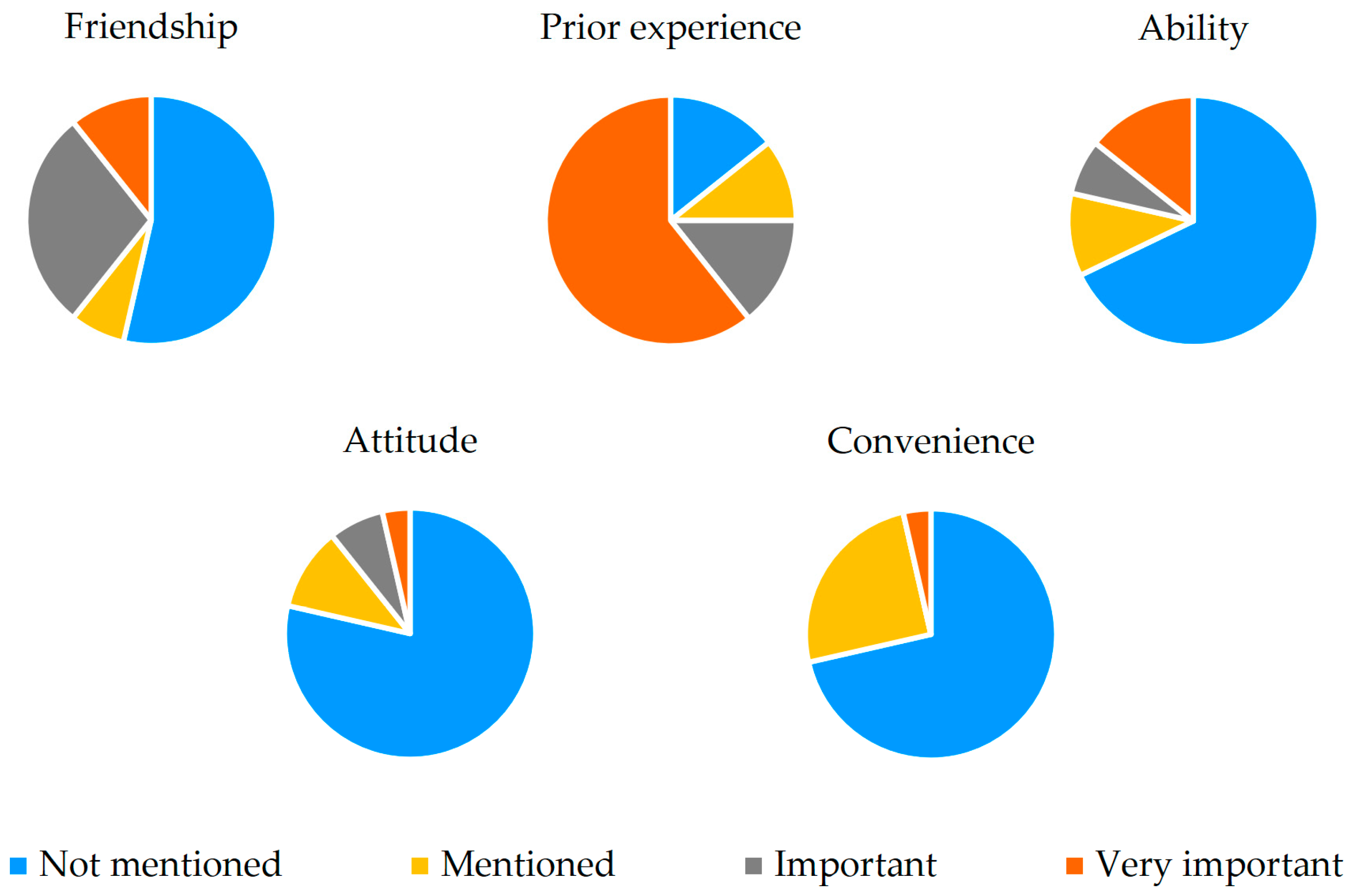

4.2. RQ2: Motives Considered during Self-Selection

4.2.1. Familiarity

“It is not my opinion that being friends is necessary for collaboration”.—Emily, group 1

“Especially if you have positive experiences with someone, you’re going to choose that person. If last time the collaboration process was not so smooth, I’m more likely to choose someone else”.—Rachel, group 7

“I had a friend and I thought she was really cool, and we went out and I really liked her personality. But she never delivered the results by the time we agreed on. And I recognized myself a little bit in this procrastination and could tolerate that up to a certain point. Then the night before the final deadline for the task, I wanted to put our parts together and saw: “Wow, there is still so much work left”. And then I had to completely rewrite it. She did not put the same effort into it. But I was her friend, so I rewrote it. At a certain point I decided for myself that I do not want to work with her anymore”.—Ella, group 3

“I can express my opinion, my partner will not be offended. You have to think less before you give your feedback”.—Olivia, group 2

“You can talk about something else in the middle of the task, that is nice. With people you do not really know, you would not do that so much”.—Sophia, group 9

“There is less of a barrier to meet up at each other’s dormitories or make a phone call to each other”.—Robin, group 1

“I know that my partner procrastinates. I know that I have to keep reminding her to deadlines, but I am used to that, I know how she is. Should this be someone else, then it would annoy me. But I know this about her and we still get along”.—Megan, group 15

“You know which one of you is better at time-management, who tends to forget things (…) You know what you can outsource to your partner and you can trust that. You know for example: the content of their writing will be impeccable, but there will be a lot of grammar mistakes”.—Michael, group 5

“I think the first phase of the collaboration will go faster, there is no more need to make agreements on who does what when”.—Rachel, group 7

“After a while, you know the writing style and the way they approach this type of tasks, and you can anticipate or build further upon them, I find that efficiently”.—Sam, group 14

“You can predict, or at least know that you will deliver a good end result”.—Emily, group 8

“Of course you will not say as quickly that you do not like something that they have written, and you will accept more of their writing, just because you know them”.—Victoria, group 3

“If you know somebody well, for me at least, it is easier to be very honest but I would bring the message in a less nuanced way”.—Chloe, group 10

“In case I collaborate with someone I know well, and I know that that person has a lot on their plate, then I would take over more of their responsibilities. In that case I would not report somewhere that she did not sufficiently contribute to the task”.—Emma, group 11

“If you do not know your partner that well, then I do not want them to say “I’ve worked with this person and they have not finished any of their work on time” or something like that. So you feel obligated to do the best you can”.—Ella, group 3

“You always tend to work in the same way, because you know it works well, but that has a downside as well. Because by always doing the same, your knowledge and skills will not be broadened”.—Natalie, group 12

“You take on a different role, maybe. Or you learn to start a project in a different manner. And you would need to push your own boundaries and learn to put yourself into a new role”.—Elizabeth, group 15

4.2.2. Ability

“I am not necessarily going for the most fun option. If possible, I always try to consider with whom I could collaborate best to gain more insights into the task”.—Matthew, group 2

“I prefer to know someone is good at writing, or supports me in what I am less good at”.—Grace, group 7

“For me it is important to work with someone who is just a little better than I am, who can lift me up”.—Lauren, group 6

4.2.3. Attitude

“I might also work with someone I do not like as much, because I know they put work into the task. So it’s important to me that people are not lazy, so to speak”.—Natalie, group 12

“I pay attention to who makes a good impression and who seems more like a sloppy worker”.—Ella, group 3

“I find it very important not only to see each other and only talk about the task. The informal aspect, to be able to laugh about something, to put things into perspective once in a while… even if the task is important for your education, I sometimes just need someone who can say “Look, it is not going to get any better than this, we will let it rest for a while” and spend some free time, a dinner or whatever, without talking about the task”.—Michael, group 5

4.2.4. Convenience

“I actually knew my partner’s friend. My partner and I were not friends per se. But our mutual friend does not take this course, and so we ended up together”.—Ella, group 3

“We just sat next to each other in the classroom when the task was explained. And I already collaborated before with my partner, so it was a logical choice”.—Jenna, group 8

“I did not have a partner yet, and I knew my partner did not team up yet with someone, so that is how it went, nothing special”.—Jacob, group 16

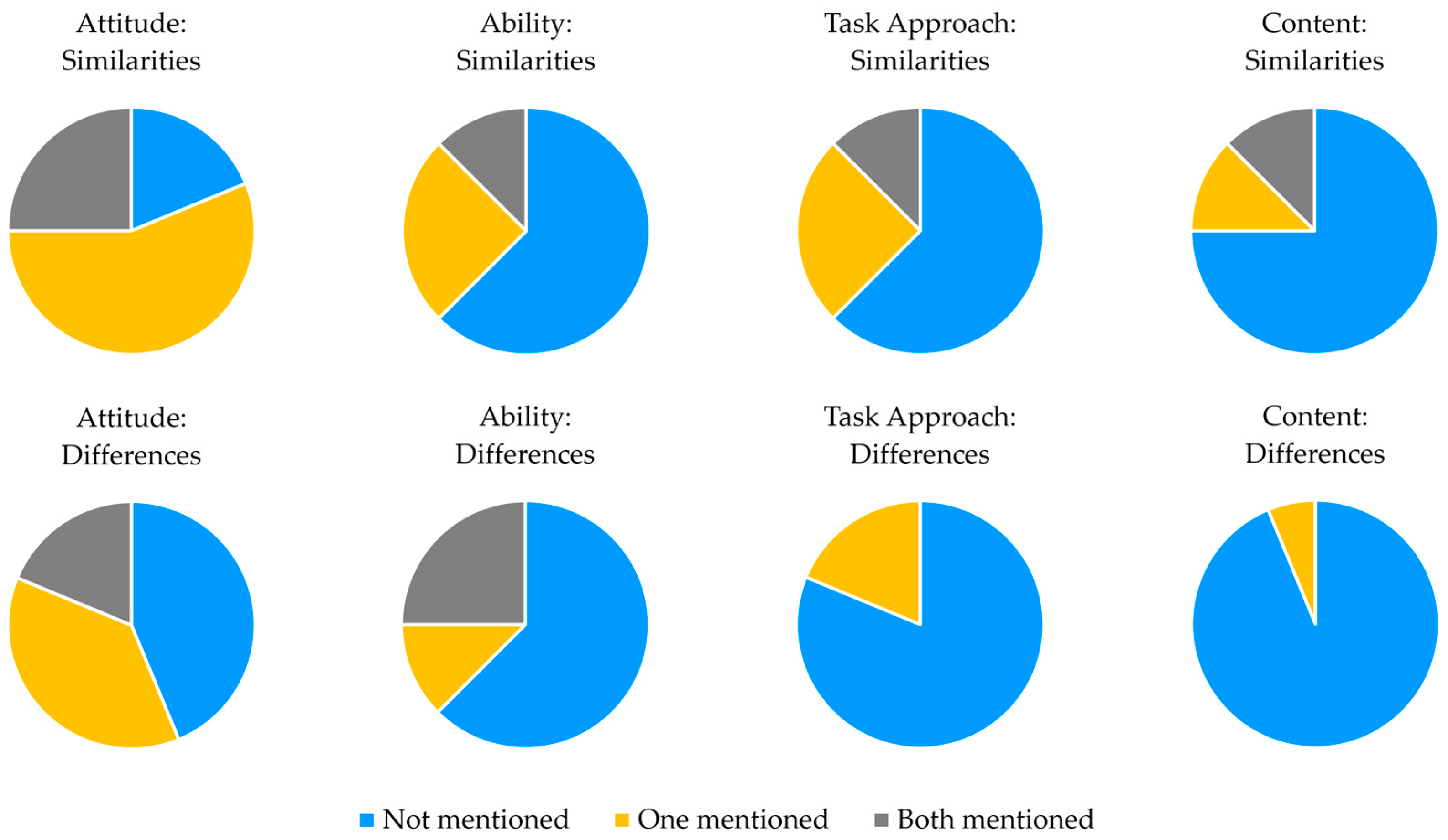

4.3. RQ 3: Similarities and Differences

“Mostly, our vision of what we want to write differs. Yet, this is always negotiable, so when our opinions do not collide, it is a positive thing. (…) And when we have a different idea, we compromise, so we always get along very well”.—Natalie, group 12

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- RQ 1:

- Preferences student-selection or teacher-assigned

- 1.

- For this task, you were asked to choose your own partner. What do you think of that? Why?

- 2.

- Do you prefer this method, or would you rather have your teacher assign you to a group? Why? (What are benefits and drawbacks?)

- RQ 2:

- Motives during student-selection

- 3.

- You collaborate with X (i.e., the partner). How did you two end up together? What made you choose this partner for this task?

- 4.

- How well do you know each other? To what extent does that matter to you?

- 5.

- From the questionnaire, I could draw that you two collaborated before. To what extent is that important to you?

- 6.

- Should you have never collaborated before with this partner, would you still have chosen this partner? Why (not)?

- 7.

- What are the benefits of collaborating with someone you know well?

- 8.

- What are the drawbacks of collaborating with someone you know well?

- 9.

- What are the benefits of collaborating with someone you do not know so well?

- 10.

- What are the drawbacks of collaborating with someone you do not know so well?

- 11.

- Could you please summarize in your own words how you select a specific partner for this task?

- RQ 3:

- Similarities and differences

- 12.

- In which ways are you similar to your partner?

- 13.

- In which way do you differ from your partner?

- 14.

- You summed up quite a lot of differences/similarities. Are these similarities and differences important to you? Why? (Would you explicitly choose someone different to you? Rather someone similar to you? Or did you not consider these differences and similarities beforehand?)

References

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T.; Smith, K. The State of Cooperative Learning in Postsecondary and Professional Settings. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 19, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhong, R.; Wang, H. Research on the Influence of Socially Regulated Learning on Online Collaborative Knowledge Building in the Post COVID-19 Period. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsa, C.; Muukkonen, H. Conceptualising Pedagogical Designs for Learning through Object-Oriented Collaboration in Higher Education. Res. Pap. Educ. 2019, 35, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolm, A.; de Nooijer, J.; Vanherle, K.; Werkman, A.; Wewerka-Kreimel, D.; Rachman-Elbaum, S.; van Merriënboer, J.J.G. International Online Collaboration Competencies in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2021, 26, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreijns, K.; Kirschner, P.A.; Vermeulen, M. Social Aspects of CSCL Environments: A Research Framework. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 48, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkens, M.; Manske, S.; Hoppe, H.U.; Bodemer, D. Awareness of Complementary Knowledge in Cscl: Impact on Learners’ Knowledge Exchange in Small Groups. In Proceedings of the Collaboration Technologies and Social Computing, Kyoto, Japan, 4–6 September 2019; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11677, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Damşa, C.I.; Ludvigsen, S. Learning through Interaction and Co-Construction of Knowledge Objects in Teacher Education. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2016, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, N.; King, J.R. Discourse Synthesis: Textual Transformations in Writing from Sources; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 36, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- van Ockenburg, L.; van Weijen, D.; Rijlaarsdam, G. Learning to Write Synthesis Texts: A Review of Intervention Studies. J. Writ. Res. 2019, 10, 402–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, M.; Solé, I. Synthesising Information from Various Texts: A Study of Procedures and Products at Different Educational Levels. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2009, 24, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivey, N.N.; King, J.R. Readers as Writers Composing from Sources. Read. Res. Q. 1989, 24, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Li, Y. The Effect of Face-to-Face and Non-Face-to-Face Synchronously Collaborative Writing Environment on Student Engagement and Academic Performance. J. Educ. Innov. Commun. 2019, 1, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Simpson, E.; Domizi, D.P. Google Docs in an Out-of-Class Collaborative Writing Activity. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2012, 24, 359–375. [Google Scholar]

- Pymm, B.; Hay, L. Using Etherpads as Platforms for Collaborative Learning in a Distance Education LIS Course. J. Educ. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2014, 55, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, B.; Fischer, F.; Mandl, H. Conceptual and Socio-Cognitive Support for Collaborative Learning in Videoconferencing Environments. Comput. Educ. 2006, 47, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Putzeys, K.; De Wever, B. How University Students Collaboratively Write a Synthesis Text. A Case Study Exploring Small Groups of Students’ Overall Approach, Their Interactions and the Group Atmosphere. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN21 Proceedings 13th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Online, 5–6 July 2021. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Khaskheli, A.; Qureshi, J.A.; Raza, S.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Factors Affecting Students’ Learning Performance through Collaborative Learning and Engagement. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 31, 2371–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavola, S.; Hakkarainen, K. Trialogical Learning and Object-Oriented Collaboration. In International Handbook of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 19, pp. 241–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sellés, N.; Muñoz-Carril, P.-C.; González-Sanmamed, M. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning: An Analysis of the Relationship between Interaction, Emotional Support and Online Collaborative Tools. Comput. Educ. 2019, 138, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Janssen, J.; Wubbels, T. Collaborative Learning Practices: Teacher and Student Perceived Obstacles to Effective Student Collaboration. Camb. J. Educ. 2018, 48, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkens, M.; Bodemer, D. Improving Collaborative Learning: Guiding Knowledge Exchange through the Provision of Information about Learning Partners and Learning Contents. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenbourg, P. Over-Scripting CSCL: The Risks of Blending Collaborative Learning with Instructional Design. In Three Worlds of CSCL: Can We Support CSCL? Open Universiteit Nederland: Heerlen, The Nederland, 2002; pp. 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hilton, S.; Phillips, F. Instructor-Assigned and Student-Selected Groups: A View from Inside. Issues Account. Educ. 2008, 25, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, S.H. Comparing Student-Selected and Teacher-Assigned Pairs on Collaborative Writing. Lang. Teach. Res. 2016, 21, 496–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.G. Restructuring the Classroom: Conditions for Productive Small Groups. Rev. Educ. Res. 1994, 64, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuitema, J.; Palha, S.; Van Boxtel, C.; Peetsma, T. Effects of Task Structure and Group Composition on Elaboration and Metacognitive Activities of High-Ability Students during Collaborative Learning. Pedagog. Stud. 2019, 2019, 136–151. [Google Scholar]

- Slof, B.; van Leeuwen, A.; Janssen, J.; Kirschner, P.A. Mine, Ours and Yours, Whose Engagement and Prior Knowledge Affects Individual Achievement from Online Collaborative Learning? J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2020, 37, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, A.; Janssen, J. A Systematic Review of Teacher Guidance during Collaborative Learning in Primary and Secondary Education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, N. Collaborative Writing. In The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching; Liontas, J.I., DelliCarpini, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. ISBN 9781118784235. [Google Scholar]

- Wigglesworth, G.; Storch, N. Pair versus Individual Writing: Effects on Fluency, Complexity and Accuracy. Lang. Test. 2009, 26, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Dobao, A. Collaborative Writing Tasks in the L2 Classroom: Comparing Group, Pair, and Individual Work. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2012, 21, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marttunen, M.; Laurinen, L. Participant Profiles during Collaborative Writing. J. Writ. Res. 2012, 4, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Luo, H.; Sun, D. Investigating the Combined Effects of Group Size and Group Composition in Online Discussion. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai, M.; Horita, T.; Wada, Y. Identifying Optimal Group Size for Collaborative Argumentation Using SNS for Educational Purposes. In Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics, IIAI-AAI, Yonago, Japan, 8–13 July 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Abuseileek, A.F. The Effect of Computer-Assisted Cooperative Learning Methods and Group Size on the EFL Learners’ Achievement in Communication Skills. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Homberg, F. The Effects of Gender on Group Work Process and Achievement: An Analysis through Self- and Peer-Assessment. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 40, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Che, S.; Nan, D.; Li, Y.; Kim, J.H. I Know My Teammates: The Role of Group Member Familiarity in Computer-Supported and Face-to-Face Collaborative Learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 12615–12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Erkens, G.; Kirschner, P.A.; Kanselaar, G. Influence of Group Member Familiarity on Online Collaborative Learning. Comput. Human. Behav. 2009, 25, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R.E. When Does Cooperative Learning Increase Student Achievement? Psychol. Bull. 1983, 94, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Rilke, R.M.; Yurtoglu, B.B. Two Field Experiments on Self-Selection, Collaboration Intensity, and Team Performance; IZA Discussion Paper No. 13201. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3590900# (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Mitchell, S.N.; Reilly, R.; Bramwell, F.G.; Solnosky, A.; Lilly, F. Friendship and Choosing Groupmates: Preferences for Teacher-Selected vs. Student-Selected Groupings in High School Science Classes. J. Instr. Psychol. 2004, 31, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Post, M.L.; Barrett, A.; Scharff, L. Impact of Team Formation Method on Student Performance, Attitudes, and Behaviors. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2020, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambić, D.; Lazović, B.; Djenić, A.; Marić, M. A Novel Metaheuristic Approach for Collaborative Learning Group Formation. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, S.C.; Aubrey, S. Impact of Student-Selected Pairing on Collaborative Task Engagement. ELT J. 2023, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, H.; Kardan, A.A. A Novel Justice-Based Linear Model for Optimal Learner Group Formation in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning Environments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassaskhah, J.; Mozaffari, H. The Impact of Group Formation Method (Student-Selected vs. Teacher-Assigned) on Group Dynamics and Group Outcome in EFL Creative Writing. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2015, 6, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Rilke, R.M.; Yurtoglu, B.B. When, and Why, Do Teams Benefit from Self-Selection? Exp. Econ. 2023, 26, 749–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Gong, J. Can Self Selection Create High-Performing Teams? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 148, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, P.J.; Carley, K.M.; Krackhardt, D.; Wholey, D. Choosing Work Group Members: Balancing Similarity, Competence, and Familiarity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 2000, 81, 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadler, M.; Herborn, K.; Mustafić, M.; Greiff, S. Computer-Based Collaborative Problem Solving in PISA 2015 and the Role of Personality. J. Intell. 2019, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Spinrad, T.L. Prosocial Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eisenberg, N., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F.; Merton, R.K. Friendship as a Social Process: A Substantive and Methodological Analysis. In Freedom and Control in Modern Society; Berger, M., Abel, T., Page, C.H., Eds.; Van Nostrand: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Zou, D.; Xie, H. Integrating Different Group Patterns into Collaborative Argumentative Writing in the Shimo Platform. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poort, I.; Jansen, E.; Hofman, A. Does the Group Matter? Effects of Trust, Cultural Diversity, and Group Formation on Engagement in Group Work in Higher Education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, A.; Marttunen, M.; Laurinen, L.; Stegmann, K. Inducing Socio-Cognitive Conflict in Finnish and German Groups of Online Learners by CSCL Script. Int. J. Comput. Support. Collab. Learn. 2013, 8, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group No. | Student No. | Name 1 | Age | Prior Education 2 | Prior Collaboration | Degree of Familiarity | Perceived Ability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a | N/A 3 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| 1b | Robin | 23 | BP | 0 | A little | I do not know | |

| 2 | 2a | Matthew | 22 | BP | 5 | Friends | Well |

| 2b | Olivia | 23 | BP | 5 | Friends | Well | |

| 3 | 3a | Ella | 22 | AB | 0 | A little | Well |

| 3b | Victoria | 21 | AB | 0 | By name | I do not know | |

| 4 | 4a | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| 4b | Scarlett | 22 | BP | 1 | Well | Well | |

| 5 | 5a | Zoey | 22 | BP | 0 | A little | Very well |

| 5b | Michael | 22 | BP | 0 | A little | I don’t know | |

| 6 | 6a | Lauren | 22 | BP | 3 | Friends | Average |

| 6b | Nicole | 24 | BP | 3 | Friends | Very well | |

| 7 | 7a | Grace | 21 | AB | 15 | Well | Well |

| 7b | Rachel | 21 | AB | 15 | Friends | Very well | |

| 8 | 8a | Emily | 21 | AB | 5 | Friends | Very well |

| 8b | Jenna | 21 | AB | 5 | Friends | Very well | |

| 9 | 9a | Alex 4 | 23 | AB | 0 | A little | I do not know |

| 9b | Sophia | 21 | AB | 0 | A little | I do not know | |

| 10 | 10a | Jasmine | 21 | AB | 2 | Friends | Very well |

| 10b | Chloe | 24 | BP | 2 | Friends | Very well | |

| 11 | 11a | Emma | 21 | AB | 4 | Friends | Well |

| 11b | Alyssa | 21 | AB | 4 | Friends | Well | |

| 12 | 12a | Natalie | 21 | AB | 2 | Friends | Very well |

| 12b | Jessica | 21 | AB | 2 | Friends | Very well | |

| 13 | 13a | Miley | 21 | AB | 3 | Friends | Very well |

| 13b | Lily | 21 | AB | 3 | Friends | Well | |

| 14 | 14a | Sam | 22 | BP | 1 | Friends | Very well |

| 14b | Nicholas | 23 | BP | 1 | Friends | Very well | |

| 15 | 15a | Elizabeth | 22 | BP | 3 | Friends | Well |

| 15b | Megan | 22 | BP | 3 | Friends | Well | |

| 16 | 16a | Jacob | 23 | AB | 0 | A little | I do not know |

| 16b | Joshua 4 | 22 | AB | 0 | A little | I do not know |

| Phases of Braun and Clarke [53] | Detailed Phases of Our Thematic Analysis Process | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Familiarizing yourself with your data | All interviews were systematically transcribed, data were read and re-read, and initial notes were taken. |

| 2 | Generating initial codes | Using Nvivo (version 12), initial categories (or main codes) were created based on the interview protocol. Each interview was coded based on these categories. For the first research question, initial categories were “teacher-assigned” and “student-selection”. For the second research question, two categories were pre-defined based on the literature review, i.e., “familiarity” and “ability”, for the third research question the categories “similarities” and “differences” were created. Within these broad categories, subcodes were created based on the data. |

| 3 | Searching for themes | Overarching themes were created. The overall main codes remained as themes. Subcategories were sometimes merged or disaggregated. |

| 4 | Reviewing themes | The themes were iteratively reviewed and revised until the themes formed a coherent pattern. |

| 5 | Defining and naming themes | All codes were named and defined in detail. |

| 6 | Producing the report | An outline for the results was created. |

| Group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b |

| Friendship | * | ➋ | * | ➊ | ➊ | ➌ | ➌ | ➋ | ➋ | * | ➋ | ➋ | ➋ | ➌ | ➋ | ➋ | * | |||||||||||||||

| Prior experience | * | ➌ | ➌ | ➊ | * | ➌ | ➊ | ➌ | ➌ | ➌ | ➌ | ➌ | ➋ | * | ➌ | ➌ | ➌ | ➌ | ➌ | ➌ | ➋ | ➌ | ➋ | ➌ | ➌ | ➋ | ➊ | * | ||||

| Ability | * | ➌ | ➊ | * | ➌ | ➋ | ➋ | * | ➊ | ➌ | ➊ | ➌ | * | |||||||||||||||||||

| Attitude | * | ➌ | * | ➊ | ➋ | * | ➊ | ➋ | ➊ | * | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Convenience | * | ➊ | ➌ | * | ➊ | ➊ | ➊ | * | ➊ | ➊ | ➊ | * | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Group No. | Attitude | Ability | Task Approach | Content | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||||

| 2 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓✓ | ||

| 3 | ✓ | ✕✕ | ||||||

| 4 | ✓ | |||||||

| 5 | ✓ | ✕ | ||||||

| 6 | ✓✓ | ✕✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ||||

| 7 | ✓✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕✕ | ||||

| 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | |||||

| 9 | ✓ | |||||||

| 10 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓✓ | ✕ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ||

| 11 | ✓✓ | ✕ | ✓ | |||||

| 12 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓✓ | ✕ | ||||

| 13 | ✓ | ✕✕ | ||||||

| 14 | ✓ | ✕✕ | ✕✕ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 15 | ✓✓ | ✕ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | ||||

| 16 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Putzeys, K.; Van Keer, H.; De Wever, B. Unknown Is Not Chosen: University Student Voices on Group Formation for Collaborative Writing. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010031

Putzeys K, Van Keer H, De Wever B. Unknown Is Not Chosen: University Student Voices on Group Formation for Collaborative Writing. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010031

Chicago/Turabian StylePutzeys, Karen, Hilde Van Keer, and Bram De Wever. 2024. "Unknown Is Not Chosen: University Student Voices on Group Formation for Collaborative Writing" Education Sciences 14, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010031

APA StylePutzeys, K., Van Keer, H., & De Wever, B. (2024). Unknown Is Not Chosen: University Student Voices on Group Formation for Collaborative Writing. Education Sciences, 14(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010031