1. Introduction

Autism is a prolific business that attracts billions of dollars worldwide for research and support services for autistic children, people, and their families. The commodification of autism has moved well beyond the domain of researchers and autistic communities to infiltrate and be infiltrated by movies, television programs, annual autism awareness days, advocacy groups, and social media posts and sites. The current “autism infodemic” consists of a plethora of multi-modal information representing varied histories, stories, and research that constructs autism in multiple ways to reflect broader cultural, political, and economic factors. Waltz [

1] highlighted the multiple representations of autism, including references to animal nature, the puzzle metaphor, military metaphors, and alien/cyborg representations. In the use of such metaphors, conceptions of autism are produced, consumed, and reproduced, and given the vast array of representations of autism, it is not surprising that different people have different beliefs and conceptual understandings about autism. The challenge this presents lies in the potential to perpetuate misunderstandings based on others’ representations without individuals being explicitly aware of these influences on their own conceptions of autism.

Early research into autism and the media, such as Manning’s [

2] work concerning the portrayal of autism in movies and the effect on public perception, found that the broader community focused on characters such as Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man [

3]. With movies forming the general community’s main frame of reference, Manning [

2] suggests that it is difficult for most people to imagine other representations or manifestations of autism. Hall [

4] (p. 225) describes the “spectacle of the ‘other’” and draws our attention to the representational practices of stereotyping that are used in popular culture and mass media. This is supported by Eastwood et al. [

5] (p. 9), who said, “Autistic people represented in film have often been displayed as an exotic other or a plot device, further embedding ableist assumptions and stereotypes”.

Hall [

4] (p. 3) stated that “representation is the production of the meaning of the concepts in our minds through language”. “It is the link between concepts and language that enables us to refer to either the “real” world of objects, people, or events, or indeed to imaginary worlds of fictional objects, people, and events”. The notion of real and fictional was of interest in trying to determine influences, such as metaphors and popular media, on educators’ and autistic adolescents’ conceptions of autism, given that the sources for people’s conceptions can be driven by both real and fictional accounts. Lived experience, as a “real account”, was expected to be of significant influence on both educators’ and autistic students’ conceptions of autism, but our research was seeking to determine other sources of influence and, in particular, whether shared or varied conceptions led to autistic students feeling supported or not in the school context. Brownlow et al. [

6] highlighted the damaging effects on autistic students when teachers made assumptions based on labels or stereotypes.

One does not need to look far to find widely differing viewpoints about autism, with Runswick-Cole [

7] highlighting the “us” and “them” model of neoliberalism, reflecting her proposition of “autism as disorder” versus “autism as difference”. She highlights that “autism as disorder” perpetuates autism from a deficit perspective, while “autism as difference” makes a case for a neurodiverse approach whereby autistic children and people are recognized, valued, and equally included in communities. Runswick-Cole [

7] and other autistic researchers [

8] support a neurodiverse approach as fundamental to improving the rights and outcomes for autistic children and people; however, access to and engagement with their research is likely to be far less than the ubiquitous autism messaging found on popular media and websites worldwide. Educators who hold conceptions of “autism as disorder” may serve to create an “us” versus “them” model in school contexts without an awareness of the influence of their conceptions on lived experiences for autistic students.

O’Dell et al. [

8] (p. 170) highlight the emergence of autism “epistemic communities”, whereby “indicators of similarities and contrast between different approaches to issues such as understanding autism” generate varied representations of autism. They note the importance of epistemic communities having shared language and shared concepts to support the legitimization of knowledge. Historically, our epistemic communities were influenced by smaller and more localized environments, but with the advent of technology and the internet, we have become a globally networked society powered by personal and digital networks. Castells [

9] also refers to the technology-driven access to information as a material culture, one in which ideas, interests, and values are socially produced and consumed. The recursive interactions between the production and consumption of knowledge and the ways in which knowledge is represented and regulated have a significant influence on identity formation, values, beliefs, and actions, and to which epistemic community one aligns. Of interest to this research was how to determine influences on educators’ and adolescent autistic students’ conceptions of autism and whether these aligned with the same or a different epistemic community.

Given that educators and autistic students find themselves working together in school-based contexts, aligned conceptions of autism along with common understandings of identity should assist in creating a more positive learning environment [

6]. Leve [

10] (p. 6) cites Hall on the value of common understandings, noting that “Hall calls this common understanding “conceptual maps” and makes the point that in sharing a roughly similar “conceptual map”, we are able to build up a shared culture of meanings and thus construct a social world that we inhabit together”. However, this research theorized that educators and autistic students may hold different conceptual maps given that they are cultural beings who may experience varied norms, rituals, language, values, beliefs, and senses of identity [

11]. Schudson [

12] (p. 6) stated, “Philosophy, the history of science, psychoanalysis, and the social sciences have taken great pains to demonstrate that human beings are cultural animals who know, see, and hear the world through socially constructed filters”. The socially constructed filters of teachers and autistic adolescents may vary significantly given their different social statuses within a school, their lived experiences, and research that indicates autistic people are neurologically different from others and potentially process information in different ways [

13].

Drawing on the research above, the key question guiding this research was: how do teachers and autistic adolescents conceptualize autism, and what influences the development of these ideas? We were particularly interested in understanding the potential influences of lived experiences for both teachers and students and evidence of any implicit influences linked to the commodification of autism. Of significance to the research was exploring how the teachers’ and students’ conceptions of autism aligned or varied and the implications of any differences in conceptions.

A primary priority in conducting the research was to ensure the research design was mindful of the needs of all research participants, but in particular the young autistic people involved. The desire to provide autistic adolescents with a sense of agency within the research process generated various ideas about methods and the value of consulting with the autistic community prior to settling on the final research design. We were also aware of the importance of conducting research deemed valuable to the autistic community. Gowen et al. [

14] highlight autistic communities’ concerns that much research on autism does not reflect their priorities. Hence, a priority for this research was to ensure pre- and ongoing consultations with members of the autistic community on the research design and methods. The following section provides an overview of the processes involved in shaping the research design and methods.

3. Theme One: The Role of Lived Experience on Conceptions of Autism

The teachers in this research brought significant experience teaching autistic students and presented as confident in their knowledge of autism. They consistently referred to their experiences of teaching in their initial responses to the word “autism”. For example, one teacher said:

The first thing that comes to my mind is around my work, in that part of my work is to help teachers help kids with autism. That is the first, the immediate response that I have…. the next…thought would be around, how do we and how does that person that we are referring to at the time, how are they coping with their autism and how are people supporting them? I think back to when I was actually teaching kids with autism in my class, with fond memories and always brings back good memories of the fun that we used to have. How we used to work together to form a team around the kid to help in the class. How we would try and help the family and the students at school.

This teacher used the word “help” to describe the support needs of autistic students, as well as characterizing families of autistic students as in need of “help” and teachers as also needing “help”. These responses problematize autism and autistic students as causing difficulties or issues that require assistance of some kind, which is provided by teachers and support staff. The narrative of autism as a problem with inherent difficulties or challenging behavior is evident in her response [

22]. The teacher also focuses on how the students are “coping” with their autism, suggesting they conceive of autism as being separate from the students.

Another teacher, also reflected on her personal experiences when she heard the word ‘autism’. She described an associated feeling of heartbreak for families and the challenges she thought that autistic individuals experienced stating:

Probably an experience rather than anything else, and that is the experience of working with children on the autism spectrum and how difficult it is for them and their families, I suppose it is for acceptance. It is a feeling more than an experience…the challenges and heartbreak for the families and all of those sorts of things that I see.

Both teachers reflected immediately on their lived experience of teaching, and although one spoke of having fun with her students, these teachers’ personal experiences led them to view autism as “difficult”. It could be proposed that if educators view autistic students as difficult, it may influence how they reproduce ongoing representations of autism. Woods [

23] talks of the “looping effect”, that is, the more an idea about autism is discussed, the more it gathers validity, even if it is not true. However, the teachers’ responses indicate this is their truth, and how these beliefs may be reframed is an important discussion. Although there is also an argument that these teachers have experienced the challenges presented to families of autistic children by current education systems and feel somewhat powerless to improve outcomes for the families,

Another teacher used the term ‘hard work’ when responding to hearing the word ‘autism’. She said:

It is complex, and there isn’t a one size fits all and it’s very difficult for our teachers and our parents and other kids to understand. I also think it can be very emotional. We have a little boy with autism and Downs (syndrome) and just to see their journey is hard work. It is hard work and people don’t understand, they think they are naughty… and sometimes they are (laughs). The complexity is the thing that comes to me the most.

This teacher explicitly linked her representation with being emotional, aligning this with the hard work of watching families’ experiences. There are extensive examples of autism popular culture drawing on the emotional work autism demands of families [

24], but it appears Mary’s responses were again drawn from her lived experience as a teacher of autistic students and her interactions with their families.

In her response to the word “autism”, one teacher said, “I think there are a lot of misconceptions, from an educator’s point of view, and I would say challenging behaviors”. This response suggests she is aware of a range of varying perspectives about autism but then focuses on challenging behaviors as the first thing that comes to mind. Her conflation of autism with challenging behaviors is not uncommon. Other researchers also report that educators use terms such as “maladaptive behavior” or “deviant behavior” to describe autism [

25,

26]. Verehoef [

24] proposes that if autism is described as a series of deviant behaviors, then how can we ever see it as natural? The concept of deficit or disorder is reinforced and is also squarely situated within the child’s behavior and actions, as opposed to educators’ responses to the child, for example, in their understanding of autistic students’ communication or learning styles.

In contrast to the teachers’ lived experiences, which reinforced their conceptions of autism as hard work, challenging, difficult, and to be “copped with”, autistic students, in response to the word autism, presented conceptions of autism as “just a word”, “viewed differently by different people”, and as providing a sense of “superiority” to others. The varied conceptions were to be expected given that the students were all aware of being autistic and reflected quite different lived experiences from those of the teachers. Of concern, the students reflected quite negatively on their lived experiences in the school context in responding to the word “autism”. One student said:

It depends on what viewpoint you’re talking from. To be honest with you for a lot of people I think it has negative connotations. It does for me. Because I think, a lot of kids, are maybe a really socially awkward kid, whereas it’s not always like that. Even if it is like that, it’s not really. Some kids just can’t help it. I mean, one of them is my other friend [who is autistic]. And you know, that’s sort of a negative and positive thing. He’s a human being, you know what I mean?

This was a powerful statement that challenges the belief held in the research literature that autistic people are unable to take the perspective of others (known as the ‘theory of mind gap’) [

27]. This statement indicated that Sarah was aware of the perspectives of others which connects with the work of Milton [

28] who proposed that, in fact, the so-called ‘theory of mind gap’ was a ‘double empathy’ problem. Milton argues that autistic people are able to communicate effectively and easily with each other, just as non-autistic people are, with challenges of shared understanding only occurring between the two groups. The student presents a plea for greater understanding from others about the differences autistic students present with, and her lived experience of a lack of understanding, supports Milton’s argument that gaps exist in generating shared ‘conceptual maps’ between autistic students and non-autistic teachers and students.

Two other students’ responses to the word “autism” did not refer directly to their lived experience but appeared to be an outcome of living in a context in which they felt “othered”. One student said, “They think you’re different from everyone else”. By using the word “they”, she is referring to non-autistic teachers and students. By using the word “you’re”, she is not separating herself from autism but viewing herself as a person who she clearly recognizes is seen as different by others. The other student described his response to the word “autism” as simply, “It’s just a word—that people sometimes take advantage of”. This pause in his response was of interest, as it may have reflected that he recognized the word related to him but was not keen to be defined by it. However, he then proceeded to note that it can lead to people being categorized by the word “autism” and taken advantage of. Perhaps this was an intentional representation based on a recent (or often-lived) experience of being autistic. He didn’t explain further (to describe being taken advantage of by whom), but his response indicated a sense of being “othered,” potentially not in a positive way.

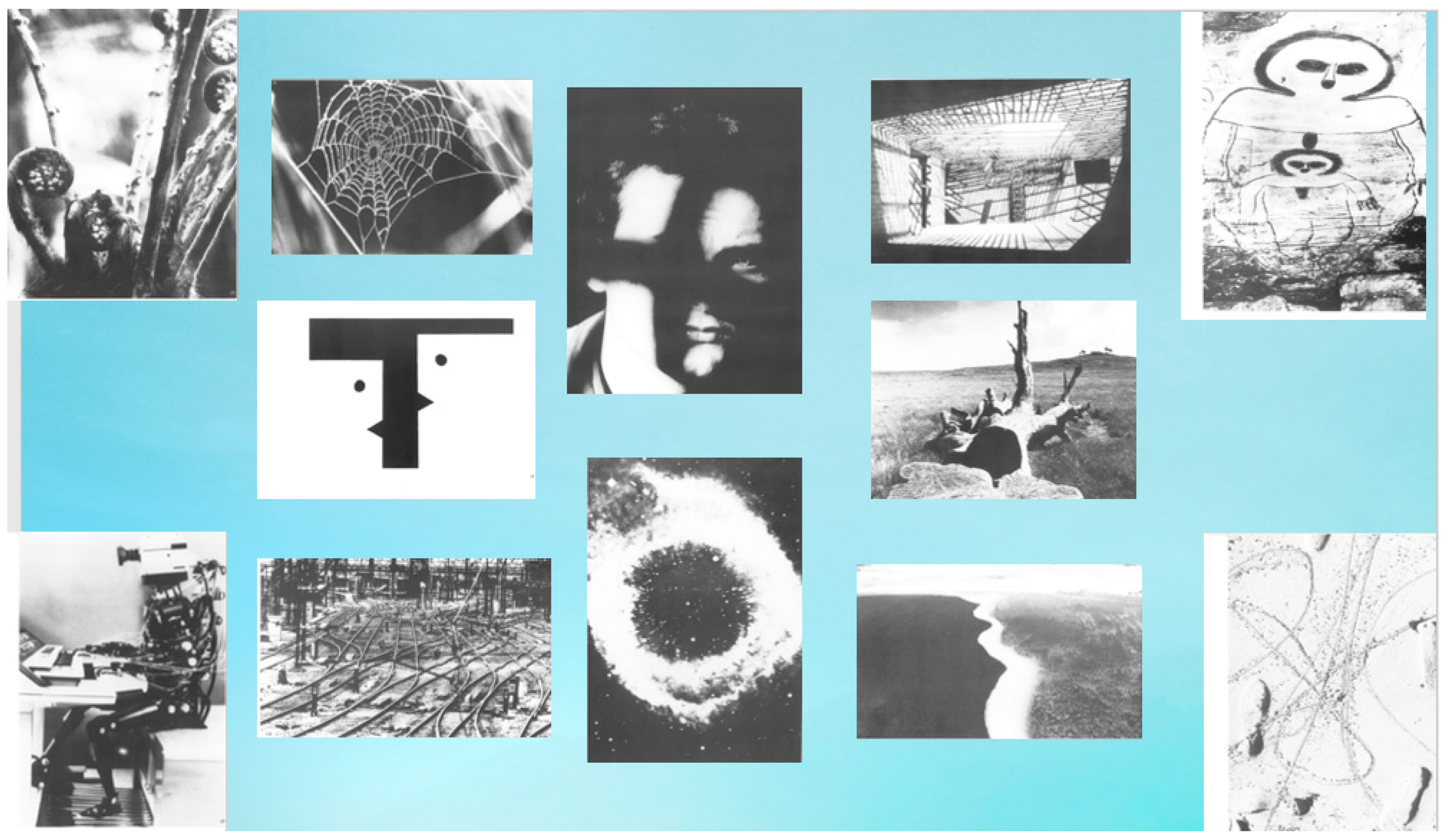

The lived experience was clearly influential on teachers’ and students’ conceptions of autism, but these lived experiences varied so much that wide gaps were evident in their conceptual maps. Of concern was that experienced teachers still viewed autism as separate from the students, while the students conceived of autism as part of who they were. They recognized this positioned them as “different” from others, but rather than this difference being accepted, they felt “othered” by those around them. These differences in lived experiences were also reflected in variations in students’ and teachers’ responses to the selection of the railway tracks image.

Comments from teachers about their selection of the railway tracks also aligned with their lived experience of teaching autistic students. As noted in the comments below, they connected the railway tracks to the challenging journeys some students experienced at school, that school may be overwhelming for some students, and the need to change direction often when working with autistic students. The words “conflict” and “complication” featured in the teachers’ comments linked again to the narrative of autistic students as challenging to teaching roles.

This one to me is again about confusion. There are so many roads leading to a destination and some people can take one path through and get there really quickly, whereas for other people it is a really difficult way to get there and they get really confused about how the journey is going to go

…I have also chosen the many train tracks because that reminds me… it’s very complicated, very busy and I think that often children with autism… their minds are very busy… this busyness of all the different railroads ‘do I take this track or do I take that track’ as the decisions that we are sometimes putting on children, or choices and it can be confusing

…they are all criss-crossing over and you can change in directions, and that is how it feels sometimes with our students with autism. We get something sorted and then you have to change track, and change track, and change track just to keep them going in the same direction.

When I look at that, sometimes in the classroom is an overload of information there is too much going on, they can’t sit and concentrate, and it is too overwhelming. Sometimes it is because the teacher needs to break down instructions, or it is the language used, or it could be too much background noise, air conditioners, or music playing in the background that the teacher hasn’t realized. There is a lot going on in that picture and sometimes that is how it is for our students in the classroom, it is very overwhelming and just too much.

The teachers’ awareness of some of the challenges created by classroom environments for autistic students’ learning is positive but there is also a sense of a deficit perspective with only the last teacher recognizing that teachers can make a difference in lived experience of students in the school context if they can address sensory challenges for individual students.

The autistic students also reflected on their lived experiences in response to their selection of the railway tracks; however, their responses focused on self-awareness of their functioning style. The following student’s comment suggests she understands her thinking style.

Sometimes even immediately I jump to conclusions or think about a lot of different things all at once. My brain is just kind of …. (laugh). I just make connections. You know what I mean when I’m trying to think about a problem. Sometimes I think of a lot of things at once and make connections.

Another student related the image to her response to challenging social situations; she said, “Kids are giving me crap”. Yeah, literally that. “Well, I go into flight or fight”. Again, this response highlights strong personal insight into how she operates in stressful situations. A third student connected the railway tracks image with his brain functioning, saying, “My brain’s just a maze”. He didn’t attribute this negatively or positively, but rather as a statement of fact. He didn’t share where the understanding came from, for example, others’ interpretation of how he functioned or his own reflection. However, his response presents insight into his personal differences.

Clearly, the lived experiences of teachers and autistic students are quite different, with teachers having a greater sense of agency in school contexts and, for the participants in this research, confidence in their knowledge of autism. The students, on the other hand, expressed feelings of being “othered” in the school context, and this contributed to their conceptions of autism as being something that was not viewed in a positive light by others. As such, there could be a shared conceptual map between the teachers and students that autism has negative connotations, but such a conceptual map does not augur well for the experiences of both groups in school contexts. How this may be addressed is considered in more depth in the discussion section. Variations in conceptual maps between teachers and students are also evident, with teachers viewing autism as separate from the students while students reflect autism as a part of their being. This too has implications for students’ sense of identity, which will be explored further in the discussion.

4. Theme Two: Influence of Autism Popular Culture on Conceptions of Autism

Although lived experiences featured significantly in the research participants’ responses, there was evidence that popular media featured in their reproduction of ideas about autism for both teachers and students. In the previous section, one teacher’s response to the word “autism” was linked to heartbreak for families, while other teachers spoke of hard work and difficulties experienced by families. The narrative of autism as a tragedy [

29] is perpetuated by the media campaigns [

30] of many disability organizations that leverage off this narrative, often infantilizing autistic people as children [

31] to attract more funding and charity donations. The tragedy/charity discourse [

32] is at the heart of the commodification of autism [

33], and it is now comparable to a runaway train or juggernaut. It has gathered so much momentum that it is hard to stop or derail, despite the best efforts of autistic advocates, and there is evidence of its influence on research participants’ conceptions of autism.

Explicit and implicit influences of autism in popular culture and the commodification of autism were evident in the research participants’ responses. The potential implicit influence of social media combined with lived experience is noted in the response from the student, who highlighted that her friend was a “human being”. The student was acutely aware that autistic people are viewed as socially awkward, in effect “othering” them. The use of the term “awkward” in her comment suggests her social filters have tapped into how autistic people are represented in social media and beyond. For example, Sheldon, from The Big Bang Theory, is represented as the awkward archetype that is reproduced and generalizes the concept of autism and awkwardness [

34].

Another student’s response to both the word autism and the railway tracks contrasted Apple and Android mobile phones. His responses suggested autistic people, with particular reference to himself, as being superior in thinking to other people. His responses reflect the narrative that is often found in popular media comparing the two types of phones, noting also the role Google plays in his information seeking.

I’m an Apple iPhone. Apple is the superior brand. And also, it was designed by someone with autism. So, it’s proven as a much better brand than everyone else…A better way of thinking in some ways. Well, a lot of people who have invented very good things out there are on the spectrum. So … you can see the evidence out there with a simple Google search.

These types of analogies of autistic people being on different computer operating systems compared to non-autistic people are not uncommon [

1], suggesting the student’s response has been influenced by social media, but one he views as relevant to his sense of identity. His social filter connects him to these propositions by others, and he takes pride in being autistic. In response to the railway tracks image, he said, “I don’t think an android would really work that out”. But then, as you can see, they’ve got the switches, so you can swap them all around. His reference to non-autistic people as “androids” incapable of solving complex problems positions autistic people as making important contributions to the world, a sentiment perpetuated by both The Good Doctor and Sheldon from The Big Bang Theory.

Two teachers made comments about The Good Doctor with one saying, “…a lot of people are saying The Good Doctor has increased their understanding of people with autism”. She expressed concern about this in recognition of autistic stereotypes and stigma being reproduced in this program. The other teacher provided a more detailed response stating:

I watch The Good Doctor because everyone does! They portray him with amazing skills. Why don’t they just portray him as a normal human being who has autism and who happens to be a doctor? They portray him as not looking anyone in the eye, and not liking to be touched… the way he talks, whoever the actor is he got that down pat we had a parent, she is quite autistic, and she talked to me exactly the same way. She would flick her head, and look at me this way and that. The first thing I thought of was, “wow, you are exactly the same as the ‘Good Doctor’.

This teacher’s responses highlight her consumption of information from the television program and, whether consciously or unconsciously, the reproduction of autism popular culture generalizations with the unfortunate comparison to one parent’s communication style. The educator moved between challenging stereotypes of autism but then replicated these stereotypes herself in her suggestion that the character of The Good Doctor reflected all autistic people with his monotonal voice, refusal to look people in the eye, and dislike of physical contact. This teacher’s response certainly indicates the influence of autism in popular media on her conceptions of autism, and these influences appear to reinforce the reproduction of autism as a “disorder” rather than a “difference”.

One teacher referred to Facebook as a source of information about autism, even though she considered herself to have expertise in the area, she stated:

I use Facebook not as a social tool to connect with my friends, it’s more about what’s out there and what pages I have liked. I know the ‘Quirky Network’ friends invited me to join, I used to work with their children, and I find that valuable as it’s an insight into parent struggles and what they are finding challenging, and it is nice to see that as an outsider, and I then try to improve my practice to be a bit more understanding and empathetic or whatever.

The reference to the “Quirky Network” suggests it is a site created by parents of autistic children. While it is positive to note that this teacher is keen to learn from parents, she focuses on parents’ challenges and struggles and clearly positions herself as an outsider. The use of the term “quirky”, though generated by the parent, is an example of many social media sites that draw on generalized traits of autism that potentially have both explicit and implicit influence on people’s conceptions of autism.

5. Theme Three: The Influence of Conceptions of Autism on Expectations and Outcomes for Autistic Students

Although the teacher participants in the research expressed a strong desire to help autistic students and their families, there was evidence of negative outcomes for autistic students. In response to the photo-elicitation activity, one teacher chose the image of a person’s face covered with a shadow of bars. She said:

This image of the man with the shadows across his face, … I think for some of the teenagers I work with it, they see a lot of darkness in their life, they don’t see a lot of hope, and it is almost like they are trying to look out and see a space, that they can find their way. It must be really challenging …. I find this really hard I find this really heartbreaking (cries).

Two students also chose this image, with one saying, “Sometimes people don’t really understand it, and it (autism) makes you feel isolated”. The other student had a very similar response, indicating that the image reminded her of a feeling of being “isolated and misunderstood”. The sense of isolation and loneliness has been reported in other research [

35,

36], with suggestions that autistic students may experience more loneliness in inclusive settings. However, these outcomes may also be related to both teachers and students having lower expectations of socialization for autistic students. In this sense, there may be an alignment of teachers’ and students’ conceptual maps with an awareness that isolation and loneliness are problems for many students. In contrast to concerns about isolation, another teacher stated:

…sometimes children are in their own world when they are on the spectrum you know that is their world and might even see it as a bubble and it looks peaceful. I think sometimes you know when they are in that phase, they are peaceful and generally happy. It just sums up that nice peaceful own world space.

It is difficult to determine if this teacher’s response is influenced by lived experience and/or by popular autism culture, but there are multiple examples of images of autistic children on the internet looking isolated from others. The teacher’s response is problematic as it generalizes the conception that autistic students prefer to be alone when research indicates they report feeling isolated and lonely, as indicated by the students in this research [

35,

36]. Rather than believing these students are happy in this state, attention to explicit support in developing friendships may be beneficial [

37,

38].

Other responses from teachers that indicate a deficit perspective on expectations and, once again, a view that autism is somehow separate from the students include:

There are always barriers to what they are trying to get across or communicate … there are usually walls that stand up in the way of getting there all of the time.

If they are socially acceptable or understand the social norms then everything else is much easier.

I have a soft spot for them, but I don’t think people understand how much hard work it is, how difficult it is for parents.

The first kid I ever saw with it [autism], I was like oh my god, and he had an obsession with switches.

Everything is black and white, very rarely is there a grey area, especially when they are way down the end of the spectrum.

These responses were somewhat surprising from teachers who were highly experienced in teaching autistic students, as they reproduced quite generalized conceptions of autism rather than focusing on individual characteristics of students’ strengths and successes.

One teacher’s response appeared to set higher expectations for her students when she stated:

But you have given me this, a get-out-of-jail-free card by saying I have autism I don’t have to do it, and we have boys over in the mainstream who do that. They turn around and say I don’t have to sit in assembly because I have autism and I turn around and say, there are four classes with kids with autism and intellectual disability sitting over there quietly so you can do it too. But it is what they have been allowed to get away with by both teachers and parents.

However, this teacher still reflects a deficit perspective on autistic students, assuming they are using their autism to “get away” with the expectations of others. Again, autism is seen as external to the student and is used to excuse them from school activities. There is no sense in trying to understand the individual needs of the students and personalizing learning options for them. One autistic student highlighted assumptions and stereotypes as having an impact on her experience of school when she stated:

…people just assume a lot about me if they hear the word, autism. They think, oh she’s going to need a lot of extra support; when—not really—if I need help I’ll just ask; … and I know there’s the connotation that some people with autism have particular struggles or particular strengths with one or another thing.

She went on to say:

Teachers try to put me in a box. And I didn’t like how the teachers had to box off anyone who had a disability from everyone else just for them to get support. I don’t think that was okay. Or even just isolation from other people, because someone has autism… like, kids with autism can’t survive in a normal classroom.

Another student also expressed frustration at the lack of understanding about personalizing learning needs. He stated:

When I need help, I ask. If I don’t need help, I don’t ask. Some of the SSOs don’t get that. I tell them, yeah, I’m doing my work, I don’t need you over my shoulder constantly, and I’ll ask when I need help. It gets kind of annoying.

All students were quite articulate in their recognition that being an autistic student brought with it a range of generalized expectations, often for lower outcomes, that had very little to do with them as individuals. One student summed this up well in her response, “…in some ways, autism is then, in turn, looked at as a negative thing because they’re only really seeing the negative side of it”. She was referring to teachers in using the term ‘they’re’ highlighting distinct differences in conceptions about how students and teachers perceived the capacities of autistic students.

The three themes discussed in the findings are interrelated and highlight that teachers and autistic students draw on lived experiences and autism popular culture to develop their conceptions of autism, but due to the differences in lived experiences and personal social filters, their conceptions often vary, leading to potential limitations in opportunities for autistic students to be viewed as capable and self-aware of their learning needs. As Hall [

4] suggests, without shared conceptual maps, people are at risk of not understanding the cultural norms, beliefs, expectations, and practices of a group in which we share a social space and relationships of importance to success in life. If educators and students are unable to share aligned conceptual maps, or at the very least understand each other’s conceptual maps, then interactions, relationships, and sense of identity may be compromised. The lived experience of autistic students in the school context may also be less than desirable, particularly if both teachers and students hold expectations of negative outcomes for their futures.

6. Discussion

The three key themes presented in the findings provide evidence that lived experience and autism popular culture both had an influence on teachers’ and autistic students’ conceptions of autism. However, these conceptions varied with teachers’ views of autism as separate from the student. Teachers viewed students as “having” autism and said that autism is a burden. Such conceptions reproduce the medical model of autism as a disorder that creates challenges for autistic students, families, and teachers. Of concern were the lowered expectations for autistic students and the recognition of their isolation and loneliness in school contexts. In contrast, autistic students conceived of autism as “difference”, with some students viewing their differences as a strength that heightened their capabilities in a range of ways. The students also recognized how others viewed them and were keenly aware that being autistic held negative connotations. These negative connotations, such as lowered social engagement expectations, often generated feelings of frustration and isolation in the school context. The students’ capacity to identify how others viewed them contrasts with popular generalizations that autistic individuals lack the capacity to understand others’ thoughts and feelings [

39]. The students’ insights align with a social model of disability whereby quality inclusion faces barriers created by the environment and others in the environment. In the case of this research, teachers’ conceptual maps act as a barrier because they continue to reproduce autism as a deficit, have lowered expectations of autistic students, and maintain a focus on helping rather than liberating autistic students from generalized views of autism.

Hall [

4] (p. 14) indicated that shared conceptual maps are critical to harmony in shared social spaces. He also noted that our conceptual maps are “unconsciously internalized” as we become members of a culture. In reflecting on the outcomes of this research, two different epistemic cultures are evident. Teachers were internalizing conceptual maps about autism from their professional roles and from their school-based work cultures, while the students were internalizing conceptual maps both thrust upon them by school-based cultures and from seeking their own autistic identity. It would seem important for teachers, in particular, to reflect on how their social filters prioritize some sources of information over others, thus creating a dominant culture in which autistic students may fail to feel a sense of belonging. Teachers should consider the value of listening to their autistic students as their primary source of information and understand the importance of creating a culture inclusive of autism [

6,

7,

8].

There was some evidence of similarities in conceptual maps between the participants, which were explicitly influenced by lived experience but potentially implicitly by external sources of information too. For example, isolation and stigma were referenced by several participants as closely associated with autism, with many noting that school contexts were often environments that perpetuated isolation and stigma. One educator responded emotionally to the heartbreak she felt for her students “trying to find their way”, while students spoke of feeling “isolated and misunderstood”. The ongoing representations of autism as being isolating and misunderstood fail to be challenged at many levels, but particularly within school contexts. Teachers should be advocates for their students, and while it was evident the teachers contributing to this research were genuinely committed to supporting autistic students in the school context, they need to consider how their framing of autism and autistic students reproduced an autistic identity to be pitied and potentially further stigmatized. If educators are framing their students from a “pitying” perspective, then it is not surprising that autistic students reported feeling isolated and stigmatized in school contexts.

Williams [

40] (p. 14) said many years ago, “Right from the start, from the time someone came up with the word “autism”, the condition has been judged from the outside, by its appearances, and not from the inside, according to how it is experienced”. The capacity to reflect on influences on personal conceptions of autism is potentially limited by the intertwined nature of how we consume, represent, reproduce, and regulate experiences and sources of information to potentially create unquestioned generalizations about autism and autistic identities. However, we believe this is an important focus for teachers and encourage them to take an in-depth look at how they develop their conceptions of autism. Du Gay [

41] (p. 12) poses questions to unearth how our conceptions form, including, “How is meaning actually produced?” Which meanings are shared within society and with which groups? What other meanings are circulating? “What meanings are contested?” We would also suggest that teachers ask themselves and others, “How do my conceptions of autism influence the educational opportunities and aspirations of the young people I teach?” and “Have I taken the time to listen to my students’ conceptions of autism and compared how they align with or differ from my own?” In listening to students’ and adults’ voices in this research, it became clear that they have much to offer others in sharing how they experience life as an autistic person and how they are positioned by others. We recommend prioritizing autistic voices as a primary source of information for teachers to challenge and re-conceive their understanding of autism. In this way, teachers and students may come to share similar conceptual maps and work together on the same “track”.